Gregory, Palatine, Roma, December 1974 (illustration credit 13.1)

Gregory, Palatine, Roma, December 1974 (illustration credit 13.1)

In late March 1974, the calm of Hockney’s Paris life was shattered. He had a call from Jack Hazan telling him that the film he had been working on for the last three years was completed, and inviting him to come over to London to view it. The trip was a disaster from the moment he arrived. “I went with Yves-Marie on the train on Sunday,” he recounted to Henry Geldzahler, “and when we arrived at Powis Terrace, it was as though we weren’t expected. Ossie has taken over the whole place, and we were just shoved into the back bedroom. Anyway it was so depressing with all of Ossie’s models running around that we immediately went out to dinner with George and Wayne.”1 Worse still was the fact that Clark had ripped out the beautiful fireplace in the studio, which had been lovingly chosen by Peter Schlesinger, leaving nothing but a large black hole. Nor had the sheets been washed. “They crackled with the filth,”2 Hockney told Melissa North. He was beside himself with anger. To compound it all, Clark let the bath run over, in doing so destroying one of Hockney’s favourite jackets. “David confused, uptight, silly, spiteful, ratty,” was Clark’s comment in his diary. “First time no clean sheets on his bed—I’ve really upset him on top of overflowing the bath, wrecking his trendy jacket and flooding Mo’s basement.”3

The following morning Hockney set off for a screening room off Curzon Street to watch Jack’s film, A Bigger Splash, which turned out to be, not the documentary about an artist that he had been expecting, but a semi-fictional account of the break-up of his relationship with Peter Schlesinger. It brought back too many painful memories. “He sat through the movie,” says Hazan, “and at the end of it I have never seen a more distraught person. He just said to me, ‘Jack, it’s too heavy. It’s too heavy.’ ”4 Hockney poured out his heart to Henry Geldzahler. “It shattered me. I didn’t know what to think or how to react. Its main story is about my brake [sic] with Peter, and then painting that picture of him looking into the swimming pool. My first reaction was that it was a schmaltzy [sic] view of an artist and homosexuality. I couldn’t understand Peter’s reactions to it, and realised he had almost collaborated with Jack on it. I had a conversation with him on the telephone, finally asking him why, when he had been living with me he had hated Jack and hated taking part in the movie … and why afterwards he had been such an eager actor and collaborator. He replied he did it for the money, which if it is true (which I doubt) seems too cheap. I hung up on him eventually …”5

Hockney attempted to cheer himself up by going to watch Wayne Sleep as Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Covent Garden, before heading off to the King’s Road Theatre to see Clark’s latest fashion show, a glamorous event bankrolled by Mick Jagger, and attended by numerous stars including Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Rod Stewart, Marianne Faithfull, Bryan Ferry and Britt Ekland. It was an evening that further blackened his mood. “Our reserved seats had been taken,” he wrote to Geldzahler, “by some drugged-up hooray layabouts, so we sat at the back. Ossie then says he had asked a ‘few people back for a drink at Powis Terrace’—which of course turned out to be 200 drugged-up boring hoorays and hangers on,—including Peter, so Yves-Marie and myself just left and went down to Mo’s basement. I left the next day after having a small row with Ossie.”6

As a result of both the film and the whole weekend, Hockney decided, once and for all, to get rid of Powis Terrace. “I don’t think I ever want to go back and work there,” he told Geldzahler, “so I’m definitely going to sell it and buy some small house or flat in central London.”7 Since Henry featured in A Bigger Splash, both in a scene at Powis Terrace and another at the Emmerich Gallery in New York, Hockney advised him to see it. “You are very good in it, but the portrait of Mo is too cruel, and I just think that it gives a wrong picture of me. There’s a scene of Peter making love to some boy—again he must have done it for money. I dread its release, yet as my first reaction had been that anyway it was far too long and boring it didn’t really matter, but Anthony Page saw it … and said he thought it had commercial potential—it’s like a real ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday,’ he said. This made me worry about it, but luckily I have some Valium.”8

Hockney was right in believing that Peter was paid to appear in the film. It had been the only way that Hazan had been able to persuade him to cooperate. “He kept asking me to take part and be in it,” recalls Schlesinger, “and I always said no. But after he’d been doing it for about two years, he took me to lunch in Soho—I remember Pearl Bailey was sitting at the next table—and I was movie mad, so I said I’d do it on the condition that it was treated like a job and I got paid for it. ‘If you hire me, then I’ll do it,’ I told him.”9 Hazan then paid him £170 as a fee, followed later on by two payments of £25 and £20 for doing the love scene. But whatever reason people had for appearing, Hockney felt betrayed. “… deep down I think I’ve been exploited,” he told Geldzahler, “not just by Jack—in some ways I sympathise with his position as an artist at taking material in front of him—but almost more by close friends, especially Peter, as I did think he should know better than Mo.”10 This preyed on his mind and when he returned to Paris, he could think of nothing but the film. His first reaction was to get it stopped at all costs. “I didn’t hear from David for two or three weeks,” Hazan remembers, “and then I got a message through Kasmin saying that they wanted to stop the movie going out, and they were prepared to pay £20,000 to have it destroyed, which happened to be the cost of the movie. There was stalemate there.”11

Hockney therefore decided to seek a second opinion, and sent Shirley Goldfarb, a keen movie buff, to London to see it. “She sat through the film,” Hazan recalls, “and when she came out she said to me, ‘Jack, this is the greatest film on art that has ever been made,’ and then she returned to Paris to relay her opinion to David.”12 The next person to see it was Ossie who said it was “truer than the truth.”13 Now that it had been validated by two of his closest friends, Hockney decided to take another look himself. “David came over, and I showed it to him again at the Trident Preview Theatre in St. Anne’s Court, which had these large glass cylindrical ashtrays and he managed to knock down two and smashed them. He kept going to the toilet all the time because he just couldn’t bear it, because although it wasn’t authentic, it seemed authentic, and showed his terrible distress at the loss of his love, Peter. He was totally distraught, and I should have felt guilty, but I just didn’t. I thought I was producing art.”14

A Bigger Splash was selected for the critics’ week at the 1974 Cannes Film Festival, and received generally excellent reviews, not least from the Times critic David Robinson, who wrote that it quite outclassed the British films showing in the main competition, which included Ken Russell’s Mahler. It achieved more than a straight documentary about a painter, he wrote, because “the images become in a mysterious way an extension of Hockney’s own vision. The colours and compositions are those of the paintings. Here is the world of the painter, his friends, his models, and the quiet rooms in which time seems arrested … the film moves in and out of the pictures.” He finished his review: “A first film of so much fulfilled ambition and so much originality disarms criticism.”15 Hockney resigned himself to the film, concluding that it would be wrong of him to try to suppress the work of another artist, after Hazan had made a visit to his Paris studio. “ ‘I’m painting this picture of Gregory and Shirley,’ ” Hockney recalled saying to Hazan, “ ‘and it’s nearly finished.’ Jack looks at it, quite fascinated, and says, ‘You see, David, that’s what you do all the time; look at what you’re doing to them.’ And I said, ‘I know, I see your point; if Shirley and Gregory say We don’t like that picture, I’m not going to destroy it, if I like it.’ ”16

As it happened, Shirley Goldfarb and Gregory Mazurovsky was causing Hockney problems, once again because of his fears about finding himself turning into a portrait painter. Rescue came from an unexpected quarter, in the form of a letter from John Cox, an opera director who was about to start work on a new production of Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress for Glyndebourne Opera House in Sussex. Glyndebourne had had a considerable success with their previous production, designed by the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster, and it had occurred to Cox that a young contemporary artist such as Hockney, who had the same strong feeling for graphics as Lancaster had, might be just the right person to create a new production, especially since he had already done his own take on Hogarth’s paintings. What he did not know was that Hockney had been an opera lover since he was a boy, when his father had taken him to see La Bohème at the Bradford Alhambra. It also occurred to Hockney that to work in a new medium was perhaps a way out of the rut he was in. “When you’re working suddenly in another field,” he said, “you are much less afraid of failure. You kind of half expect it, so therefore you take more risks, which makes it more exciting.”17

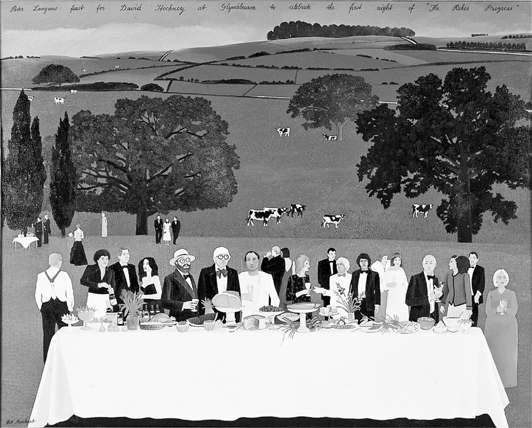

The Glyndebourne Picnic, 1975 (illustration credit 13.2)

The weekend of 14 June, Hockney, Yves-Marie Hervé and Gregory Evans went to Glyndebourne to watch a production of Richard Strauss’s Intermezzo, directed by John Cox and starring the great Swedish soprano Elisabeth Söderström. It was only Hockney’s second visit, his first having been in the sixties to see Massenet’s Werther, and he loved it. “We stayed in the house,” he recalls, “and we were having dinner with the owners, George and Mary Christie, in the dining room and I remember hearing Gregory saying to a woman sitting next to him that he didn’t know a thing about the opera. And I thought, ‘Good for you Gregory admitting that.’ Later he used to tell me how he used to be quite intimidated by some of the Opera Houses I’d taken him to, but he said, ‘Backstage it’s just show business.’ ”18

Despite falling under the Glyndebourne spell, Hockney still had reservations about taking on the job. “I felt I didn’t know enough technically—the only thing I had ever designed for the stage before was Ubu Roi.”19 John Cox immediately put him at his ease. “I told him we had plenty of people at Glyndebourne who would help him with the working drawings and with colour. I also told him it was a process of development, rather than anyone just saying, yes, that’s lovely. Having finally accepted it, he then asked me what I wanted, and I told him that by asking him I was looking for something a little out of the ordinary, which he would initiate and between us we would then develop.”20

As soon as Hockney read the libretto, by W. H. Auden and the American poet Chester Kallman, he was transfixed. “I loved that straight away,” he wrote. “It was … a wonderful, witty, very literate libretto—which not all operas have.”21 The music he found more difficult, though he was charmed by Baba the Turk’s “Chatterbox” aria in the second act when she sings, “As I was saying, both brothers wore moustaches” and breathlessly lists all her favourite treasures—among them snuffboxes, statues of the Twelve Apostles, mummies and the Great Auk. The more he listened to the score, however, the more beautiful he began to find it, and his discovery within it of an element of eighteenth-century pastiche made him decide to return to Hogarth’s paintings for inspiration.

That the Glyndebourne commission had come about at exactly the right point in Hockney’s career is reflected in a review of an exhibition of some of his recent drawings, which opened in July at Garage Art in Earlham Street, Covent Garden. Though the critic Paul Overy admired the skill with which he captured the “foibles and eccentricities” of subjects such as Kasmin, Warhol and Geldzahler, and was impressed by “a surprising understanding of the way a woman projects her sexual personality through her clothes and poise” in the coloured drawings of Celia Birtwell, he sensed that the artist had come up against a wall. “… as with much of Hockney’s recent work, one feels he has become too wrapped up in this world in which he moves … Hockney’s talent needs themes (literary, usually) which extend it beyond the immediate circle of his personal world.”22

Before he could give The Rake’s Progress his full attention, there were pressing problems to deal with. One was his rapidly deteriorating relationship with Clark, whom he was now desperate to remove from Powis Terrace. Their friendship was compromised because Celia was threatening Clark with divorce owing to his heavy drug-taking, his promiscuity and his violence towards her, and Hockney, now nicknamed “Mr. Magoo” by Clark, had, not surprisingly, taken her side. “Mr. Magoo whining from Bradford,” wrote Clark in his diary on 5 July, “—move out by the end of this month etc,”23 and two days later, “It’s a lovely day but at 11:30 David came in on the warpath and played all his old songs again including two new ones: he’s going to store the furniture and cut off the telephone.”24 Having finally got Clark’s agreement to leave by the end of August, Hockney told Mo McDermott, “Do make sure he doesn’t pinch anything,”25 a sensible precaution as it turned out, as Clark confided to his diary on 29 August: “11 o’clock the big move to Cambridge Gardens. Ordered a telephone to be installed. The beasts won’t put in the pink thirties phones. Dare I take them from Big Brother Hockney?”26

On 2 September, Clark noted, “Organise my bed, work-room and laundry and final exit from ‘Doomsville’ Powis Terrace.”27 For Hockney, however, this was by no means the end of the story, since he was inextricably bound up with the Clarks and their unravelling relationship. There were times when he muddied the waters, rather than pour oil on them. On a visit to London four days later, for example, he took a gang of friends including Celia to Odin’s for dinner. “At one point the conversation came round to what we might all really like,” Birtwell recalls, “and I said, ‘A diamond ring,’ and David, who had had a few drinks, said, ‘I’ll buy you a diamond ring, love. Come round tomorrow morning and we’ll go and buy one.’ So in the morning I went round to his studio and he’d quite changed his mind. I felt quite embarrassed. Obviously he wasn’t lit up any more when he thought about it. Anyway, Maurice Payne happened to be there and he said, ‘Come on, David, if you don’t go now you’ll never get there before the shops close’—it was early closing on a Saturday—so we tootled off to Kutchinsky in the Brompton Road. They kept bringing out these modern settings and I said, ‘Well, I want one that looks like it came out of a Christmas cracker,’ and David said, ‘Well, why don’t you tell them, lovey?’ So I got this lovely three-carat ring. Of course he didn’t want me to tell Ossie as he felt guilty on his behalf that he’d bought me a diamond ring.”28 When Clark found out, it did little either for his self-confidence or for his feelings towards Hockney, who, he was now convinced, was pushing Celia to divorce him.

Things eventually came to a head in October, around the time of the opening of David Hockney: Tableaux et Dessins, Hockney’s first retrospective in Paris. This show, at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in the Louvre, consisted of thirty paintings and seventy-five drawings, the majority of them from 1970 onwards, and they included the three paintings and most of the drawings he had completed in the Cour de Rohan. Hockney chose the pictures himself, and there was only one that he had to fight for, which was Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy. This was because the Tate Gallery claimed it was too fragile to ship. Hockney was furious and demanded a meeting with the chief conservator, a Hungarian called Stefan Slabczynski. “He was in the cellar,” says Hockney. “I said, ‘Where are the cracks?’ He said, ‘They haven’t occurred yet.’ I went up to see Norman Reid, the director, and I said, ‘The conservator doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with it yet. If something happens to it, I’ll repaint the whole bloody picture for you. Really, it’s not fair—you won’t lend a picture for a British artist having a big show in Paris—I’m appalled.’ ”29 The fuss he made was worth the trouble: Reid finally relented, and the picture went to the Louvre.

Stephen Spender wrote the introduction to the catalogue. The celebrated English poet had been an early collector of Hockney’s work, buying etchings from him while he was still at the Royal College, and had been responsible for introducing him to Christopher Isherwood. They had subsequently formed a friendship and had collaborated on the Alecto edition of the Cavafy poems. Spender compared Hockney and his contemporaries to the irreverent and antisocial tradition of art that emerged after the Industrial Revolution, as exemplified by the Pre-Raphaelites, such as Samuel Palmer and, particularly, William Blake, an artist who “remained outside the main tradition all his life, mocking at the religious and artistic institutions of his time, and producing his own totally original poetry and art.”30 Also included in the catalogue was an interview with the influential French art critic Pierre Restany, in the course of which Hockney talked about his experience in Paris. “It’s very British,” he said, “to go abroad to see something unusual and paint it … I need constant stimuli of all kinds, visual and others, that is why I travel a lot and enjoy working in lots of different places … in the paintings and drawings I’ve done here there is much more of Paris than there is of London in all I’ve been able to do in London. The reason is simple: it is easier for me to get the necessary detachment in Paris because I don’t understand much of the French character or the language. But on the other hand I know how to use my eyes and I like the sensation of detachment I can experience in Paris and which stimulates my work.”31

The show opened to the public on 11 October, and the night before, Hockney’s friends flew in for the private view. Clark was not among them. “Celia goes to Paris tomorrow,” he wrote in his diary on 9 October, “and I thought of going myself—but got very negative vibes from Mo who I spoke to on the phone—David is very off me (I hope he doesn’t brainwash Celia too much).”32 The private view was a glamourous affair, with a dinner for sixty afterwards at Maxim’s, which was paid for by an American socialite, Barbara Thurston. “She had bought a painting of mine,” Hockney recalls, “and she was one of those rich women with quite a bit of money and not many friends who thought that if they bought a painting they could take you over.”33 Kasmin remembers her as being “dotty about David. She wanted to be in the game both as a patron and a friend, and in the end she was pleading on her knees to be allowed to give the big dinner for the opening, and she forked out for a pretty grand dinner … The thing was that everyone was competing to capture a bit of the Star. It was rather like having Elvis Presley around and people asking, ‘Who is going to hold the autograph album?’ The show was a big deal for David.”34

“To stand in a clear space,” wrote the Times critic, Michael Ratcliffe, “with the sleeping nude of The Room, Tarzana to one’s left, the arrested sensations of A Bigger Splash to one’s right, with the parquet floor underfoot ending in four high windows and beyond them four stone arches of the Rivoli arcade, the eye finally resting on the scrawled announcements of Bar Mona Lisa and the Tentation du Mandarin boutique, is to feel for a moment the astonishing effect of actually standing inside a painting by David Hockney.”35 Out of everything on show, Ratcliffe selected the crayon drawings as his favourites. “The exuberance and economy,” he noted, “with which he has taken the child’s scribbling toy and transformed it—particularly in the portraits of Mark Lancaster, Mo McDermott, Peter Schlesinger, Ossie Clark and, above all, Celia Birtwell, make these in some way the crowning, sophisticated glory of the Paris show.”36

When Birtwell returned home, Clark made one last attempt to persuade her to have him back, telling her he was working hard on a new collection and had been four weeks without drugs. But to no avail. “Celia remains firm,” he wrote, “—she rubbed it in about Paris: wonderful party, photos with St. Laurent etc … I left Linden Gardens in tears.”37 Things came to a head the following day when Clark, who had been drinking heavily, went to see his lawyer to discuss the divorce, and discovered during their conversation that Celia had had a secret affair some years previously with the illustrator Adrian George. On hearing this he became, as he wrote in his diary, “like a bull with a red flag … So I split to Linden Gardens and was so furious I beat her and kicked her and her nose was a bloody mess—then I forced her to speak to her lawyer lady, and it was she who sent the police round and told me to leave …”38 A few days later he was in Paris on a working trip and went to a party given by Hockney’s French dealer, Claude Bernard. Among the guests, he wrote, was “big-mouth Shirley Goldfarb, who said to me, at the top of her voice so everyone could hear, ‘You can break your wife’s nose but you’re still very sexy to me.’ ”39 Hockney had made sure that everybody knew what Clark had done.

For Hockney, there was one downside to the success of this show: the publicity around it alerted people to the fact that he was now living in Paris. Then, a few days after the opening, Jack Hazan’s film opened in a small art cinema near the Étoile. “The film became a great success in Paris,” Hockney wrote. “… people kept stopping me in the street: loved your film. My film!…They would go to the film, then go to the exhibition to see the real paintings. People say it was a marvellous experience to watch the film and then be able to go and see the real paintings.”40 But for Hockney, now wanting to throw himself into working on his designs for The Rake’s Progress, which he had promised to deliver by Christmas, life and art were converging uncomfortably. “A lot of people were coming over and coming to see me,” he says, “and I thought, ‘This won’t be very good,’ so I took Mo and we went to LA and took a suite in the Chateau Marmont hotel.”41

Hockney’s research for the Glyndebourne project had led him back to Hogarth’s engravings of The Rake’s Progress from his original sequence of paintings: he felt that Hogarth’s precise cross-hatching technique, in which shading is achieved by the drawing of closely spaced parallel lines set at an angle, perfectly suited the jagged, linear character of the score. Stravinsky’s music, he thought, “was a pastiche of Mozart’s, and my design was a pastiche of Hogarth’s.”42 He was also convinced that the setting must remain in the eighteenth century. “I thought you couldn’t put it in the twentieth century,” he said. “The story would seem a bit too ridiculous. Even in the nineteenth century it would seem ridiculous. Instead of being at first a kind of innocent, you’d have just thought [the Rake] a fool straightaway, and therefore less interesting. I told John Cox this before I began. I said…‘Somehow we have to look at the eighteenth century and give it a twentieth-century look,’ which of course is easier than one thinks anyway. You can stylize it.”43

Apart from wanting to get away from what he would have called the “natterers,” there was another, more emotional reason why Hockney wanted to do the designs in Hollywood. Stravinsky himself had lived at the Chateau Marmont from March to April 1941, had first seen the Hogarth paintings at an exhibition in Chicago in 1947, and had written the opera in Los Angeles. Hockney left for LA on 25 October, with a penitent Mo McDermott. McDermott was in trouble on two counts, the first being that he had been plundering the Powis Terrace wine cellar. “I used to go to Burgundy with Kasmin to buy wine,” Hockney recalls, “not Rothschild-style wine, but good quality. I must have had about two hundred bottles. Then I went away to Paris, and when I came back, it was all gone. Mo had been saying to people, ‘Have a glass of plonk,’ and he’d been pouring them my nectar.”44

Worse was his heroin addiction. There are references in Ossie Clark’s diary to McDermott being “smacked out,” a situation which Hockney had only just discovered. One problem had been that McDermott’s whole life had revolved around Hockney, and with Hockney away in Paris, there had been nothing to occupy him. “I had left Mo in London and he had moved into the basement of Powis Terrace,” Hockney recalls, “but the moment I wasn’t there, there was nothing for Mo to do, and he didn’t keep asking me what he should do. Then I found out that he’d got hooked on heroin … people were quite prepared to let him have the drugs and pay them later, because they knew he would somehow get the money from me. Of course, I didn’t know this was going on. When I was told about it, I came over and threw everybody out—the basement was full of about twenty people. I then got Mo into some clinic, the first of many times I dried him out.”45 The heroin addiction also explained a number of missing drawings. “I used to see people with drawings on their walls which would say ‘For Mo With Love.’ I gave Mo a lot of drawings if he liked them, to put up on his walls, and then as soon as they got to be worth a hundred quid, he’d start selling them. Then he used to steal drawings and sell them. I just wish he’d asked.”46

Along with a newly clean McDermott, Hockney also took with him to Chateau Marmont the original recording of The Rake’s Progress, directed by Stravinsky himself, and a set of very expensive pens, with red, blue, green and black inks, sourced in Germany. They borrowed a record player to listen to the music, and, working in a small apartment at the hotel, they completed sets for more than half of the eight scenes that made up the opera, making meticulous scale models in cardboard, each one 16 × 21 × 12 inches in size, the cross-hatching done in the colours that would have been standard for printing inks in the eighteenth century—red, blue, green and black. McDermott turned out to be an invaluable asset. Having once worked for the celebrated theatre designer Ralph Koltai, he understood the process by which ideas on paper become reality. “Mo advised me straight away to make models,” Hockney wrote, “because, he said, if you only make a drawing, somebody else then translates it into the space. The moment he said that I thought, I don’t want anybody else to do that, I want to do that myself. So I thought, I will make scale models. I wanted pictorialism, I wanted to bring my own attitude to sets.”47

On 27 November, Hockney flew to Paris to meet his parents and his brother Paul and family, for whom he had arranged a trip to see his show, while McDermott travelled to London with the models to prepare for a meeting with John Cox. Flying from Heathrow, Kenneth had a small problem with security. “Comical when we checked thro (precaution against carrying bombs),” wrote Laura, “as Ken made a ‘Ping’ sound—had to go back—same again—thought it was his ‘hearing aid’—but he said ‘Don’t think I would carry guns. I’m a pacifist.’…Met by David. Went to Hotel and then on to exhibition at the ‘Louvre.’ We all enjoyed it & thought exhibits just wonderful … David very tired after travel from California and time change.”48 The following morning they went to David’s flat. “He, much refreshed, did drawing of me. Shirley called with ‘Sarah,’ little dog. We all went to the ‘Coffee Pot’ (lovely restaurant) for meal & dog sat on a stool covered with serviette at table. Other dogs too, but very well behaved. They certainly respect dogs in Paris!!! I hoped to do some shopping while Dad was sitting for portrait—But he kept falling asleep, so David could not go on … Later, walking back through Montmartre … a pavement artist wanted to draw Lisa—but she said, ‘Oh no! My Uncle is a famous artist!’ ”49

The following week, John Cox and all the Glyndebourne production team came to London to look at the completed work. “When I showed what I had done to the people at Glyndebourne,” Hockney recalls, “they were amazed that I had made models. They had expected me to do just a few drawings. What I didn’t know at the time was that some of the people thought what I was doing wouldn’t work at all, but they didn’t say so. I’m glad of that because I think if they had they would probably have put me off; I would have believed them, thinking they knew more about the theatre than I did.”50 What the doubters felt, but did not say, was that cross-hatching on such a massive scale was simply too mad an idea and would never work. As it happened, Hockney himself had doubts, and went down to Glyndebourne to test his idea. “We made lots of samples of cross-hatching in different sizes, and hung them up on the stage. I sat at the back of the theatre with binoculars, deciding what the scale should be. If it was done too small, it would look like a solid colour. If it was too big it would look like a chequerboard—and that would be ridiculous. So I made some calculations and came up with the exact size.”51

Having delivered the finished models to Glyndebourne, from where they would be taken to Harkers Studio in Bermondsey to be translated into full-size sets, Hockney took a much needed break. This also had a romantic element to it. For some months he had been feeling a growing affection for Gregory Evans, largely based on their mutual love of art, and Evans’s quick, dry wit, which made Hockney laugh, particularly in the way he would take things literally. They were once hiring a car, for example, and the girl at the car-hire desk asked Gregory if he also wanted to drive. “Oh, you mean it’s got two steering wheels?” he said.52

It was on their trip to see Intermezzo that Hockney realised how his feelings for Evans had deepened. “Gregory fell asleep on the train returning from Glyndebourne,” he later wrote, “and I thought he looked very sweet because he was wearing a suit, something he does not normally wear. In most pictures he is very casually dressed, but for Glyndebourne he borrowed a suit from Ossie Clark. I thought he looked very handsome and suddenly saw him in a slightly different way …”53 They went to Rome for a few days, where Hockney drew his new lover sitting among the ruins on the Palatine hill. “It was the first time I’d ever been to Italy,” Evans remembers, “so it was very exciting. We didn’t do that much, because we weren’t there for very long, and most of the time I ended up posing for him. He drew me a lot in those days, and he always seemed to capture something in me that I can relate to. He presented a side of me that I was unaware of, and the drawings gave me a bit of identity that I didn’t have before, that I hadn’t seen.”54

That Hockney was serious about Evans is clear from the fact that he invited him to join him in Bradford to celebrate the eightieth birthday of his mother’s oldest sister, Rebecca, known in the family as Aunt Rebe. “Busy all morning preparing a cold lunch,” wrote Laura in her diary. “At 2:30 p.m. David, Margaret & Gregory arrived. Had cup of tea and David suggested going to Harry Ramsdens for ‘Fish & Chips.’ Left my meal covered and all went to Guisely. Returned to Eastbrook for 4pm. Met old friends and had a happy birthday tea … Rebe was delighted—looked lovely in her black gown (1935) but ‘up to date.’ ”55

Evans loved the trip to Yorkshire. “I felt incredibly at home there,” he recalls, “as it didn’t feel to me that different in spirit to Kansas, which is where my parents were raised. It was dark and full of Gothic gloom, which appealed to me.”56 The party took place at Eastbrook Hall, and later that night he had his first proper meeting with Kenneth Hockney. “David’s father was magical, and eccentric. I remember we came in late and he was up tinkering. He had this twinkle in his eye as he smiled, and he was excited and wanted to show me all his current projects. The first thing he wanted to show me was this old adding machine which he had converted over from the old system to the decimal system, using dayglo stickers. Then he showed me other things he was working on, like decorated postcards and the posters that he’d made for his anti-war marches. Then—this was what I thought was brilliant—he had a recording of a train which he had taken, and he had the recording machine under his chair in the kitchen near the fire, so he would take naps in his chair and relax listening to it. He was quite right. Nowadays people sell those recordings to help you sleep. He was avant-garde.”57

Gregory Evans brought new happiness into Hockney’s life at a time when he was under considerable stress, not just from the huge task of designing his first opera, but from the ongoing dramas surrounding Clark and Birtwell, McDermott’s heroin addiction, and the continuing fallout from Jack Hazan’s film. The last finally came to the attention of Hockney’s parents in late March, after a write-up in the Bradford Telegraph and Argus. “It was rather a shock,” Laura confided to her diary. “At first it did not hit me—I guess I am very naive—tho I’m not quite ignorant. I am very sorry David has allowed himself to be filmed in these private corners of his life, whatever he feels about it. Publicity can be very cruel. He is famous & well liked & well loved—but there are always those ready to see evil rather than good. Sometimes I feel choked. Sometimes I feel who really cares!! I mean in the world! Of course I care—he is my darling boy & he has been lonely & down & distressed—but he has stood alone!!”58

It was hard for Laura, who felt embarrassed by the publicity, and when she went to chapel on Sunday, she was convinced that everyone was staring at her, especially since the pastor, the Reverend Thewliss, gave his sermon on “The Prodigal Son.” “In my heart,” she wrote, “I was running to meet David—oh how I love him!”59 After the service, Mrs. Thewliss tried to reassure her by telling her that the film was not showing in any public cinemas, but only at certain “clubs” and that she should not worry. When Laura did finally see the film two months later, after it had opened in Bradford in a public cinema, she found it on her first viewing “a revelation—suppose I am a very slow learner & because my upbringing puritanical—but am eager to learn & to broaden my mind according to the times without lowering my standards and principles.” She went a second time with one of her sisters, writing afterwards, “If I had not known the people taking part, I don’t think I should have been interested—but I felt no qualms about David & saw nothing ‘awful.’ He I suppose lives a very different life to ours—but I can accept it & only pray that my boy keeps clean & good as he is always to us. I have learned to accept the world & our beliefs in a broader way & realize how much more our children have gained knowledge & understanding more than ever we did.” Kenneth held no such enlightened views when he delivered his verdict. “It was just ‘muck,’ ” he told her, adding that David should “get some different friends.”60

Hockney’s drawings of Evans in Rome were shown in Paris in April, at the Galerie Claude Bernard, in the Rue des Beaux Arts. Claude Bernard, a wealthy dealer who represented Francis Bacon in Paris, loved stars, and had seen at once that having Hockney in his stable would bring a lot of kudos to his gallery. His first show, David Hockney: Dessins et Gravures, consisted of thirty-one drawings and thirteen etchings, including many sketches of Yves-Marie Hervé and Gregory Evans, portraits of Kenneth and Laura Hockney, Man Ray and Douglas Cooper, several studies of Henry Geldzahler, including one of him nude, and a number of drawings of Celia Birtwell, which also included two nude and one semi-nude study. “I think the nudes were done in Philippe de Rothschild’s house outside Paris,” she recalls. “I posed nude for him there, which is something that my mother said you should never do.”61

The show was a triumph, a dazzling demonstration of technique that proved that when it came to draughtsmanship, there were few artists to touch Hockney. Among them all was one nude study of Evans, drawn in coloured crayon, which brings out a touching vulnerability in his character. “His coloured drawings were very hard to sit for,” Evans says, “because they could take two or three days. To begin with it is seductive, and you feel flattered. Then reality sets in, when you think about how many times your leg goes numb, or your arm goes, or you’re drifting off to sleep. I’ve never said no, not now, which is probably my own vanity. David can be overwhelming, because in the end it is the David Hockney show, and that’s the way things are.”62

At Glyndebourne, they were working overtime to turn Hockney’s vision into reality. “Unfortunately, David got all the measurements completely wrong,” George Christie remembers. “We were using imperial measurements at that time, and he was using metric, so it was a real nightmare to begin with, because nothing fitted properly and we had to translate everything.”63 When the first set was finally installed, Hockney came down to take a look. “When he saw the opening scene, he simply couldn’t believe that all the cross-hatching, when brought into the theatre in a magnified state compared with his small drawings, came out completely right. He was in absolute awe. He didn’t believe they would translate so perfectly and just stared at it absolutely enthralled and bemused that people could do this. It was a skill that he was completely unaware of, and as soon as he saw what was going on, he became fascinated and very involved in the whole process, and started painting some of the props himself.”64

Though Hockney took terrific pride in what he was doing, he also welcomed the input and experience of the other departments. “An example of this,” Christie recalls, “was when the wig department didn’t get a clear picture from him as to what he wanted so far as the wigs were concerned. So they then decided that they would do some multicoloured string wigs, where you take different-coloured strands of wool and knit them together so you get a kind of Neapolitan ice cream of a result. They did this using quite sturdy pieces of string, which, when all put together, formed the wig. David looked at this and he was absolutely in heaven. He adored this inventiveness.”65 John Cox concurs that the cohesion on this production was tremendous. “It is impossible to exaggerate the genius of David’s work in this, but of course I brought it to life, so it was a perfect convergence of talents and ideas. He was never dismissive of ideas. What David gave us in the model, and what we then adapted so that it would fit this stage, was of a very powerful integrity, but it did give room to move, and that was very important, and he was very keen on that. He was keen on the idea of collaboration, which nobody expected.”66 All through the month of June, Hockney worked onstage at Glyndebourne helping to put the finishing touches to the production. He was completely engaged in the process, even to the point where he put his camera down. “I did not take a great number of photographs,” he wrote, “partly because there was a lot of work in putting on the production, and also because in taking photographs you’d have to somehow isolate yourself from the production work: you can’t bother too much with the camera, your loyalty is to the theatre production.”67

The opening night of The Rake’s Progress, 21 June 1975, Midsummer Night, was a never-to-be-forgotten occasion. The master of ceremonies was Peter Langan, who devised an evening of eating and drinking that would meet the demands of any rake. It was agreed with the Christies, though it had never happened before, that Langan would be allowed to take over the whole of Glyndebourne’s front lawn, where he would set up long tables and chairs. “The first thing I remember about the incredible event of the opening night,” John Cox recalls, “was that we dress-rehearsed the dinner, because Peter didn’t want anything to go wrong … He arrived with some extraordinary food and a few tables and chairs and some assistants to whom he gave instructions, and they shared ideas and so on. It was very, very carefully planned.”

Langan stage-managed the evening and Hockney cast it, with a glamorous cross-section of friends from his past. His parents were not included, having attended the dress rehearsal on 19 June, which Laura described as having been “thrilling and lovely.” On the first night everyone gathered outside Odin’s, where a coach was awaiting them. There was champagne on the bus, which got everybody into high spirits, while Tony Rudenko, a friend of Wayne Sleep’s, handed out LSD to any takers, including the brewing heiress Henrietta Guinness. It was a perfect balmy June evening, and when the coach arrived and the guests spilled out onto the lawns, they were met with a fairy-tale scene. “Peter had made a table along the length of the Glyndebourne ha-ha,” George Lawson remembers, “and put silver candlesticks and cut flowers on it with a white linen tablecloth. It was a wonderful sight.”68

Fuelled on champagne, Hockney’s guests joined the rest of the audience in the auditorium for curtain-up, and the excitement was palpable. “The audience was gung-ho for it,” John Cox says, “and it wasn’t just David’s friends. We all had people down, who were determined to make the evening history, and that made a marvellous core of response. The whole thing had an incredible buzz and brio to it.”69 When they filed out of the theatre for the dinner interval, the bacchanalian scene included handsome Cuban waiters handing out more champagne and the tables now groaning with food. The cover of each menu had a Hockney drawing of Langan and his French wine merchant, together with the words “An Evening of Excess.” “The picnic was supposed to be for about thirty people,” recalls Hockney, “but Peter took 120 bottles of champagne and none went back. I did point out to him, ‘That’s four bottles each, Peter!’ The food was fantastic—enormous lobsters, best hams, marvellous smoked salmon—he knew where to get the good stuff. It was spectacular.”70

Not everybody managed to make the second half. Henrietta Guinness, for one, high on LSD, was found head down in a flower bed, and Peter Langan was later scooped out of the ha-ha. For those who did, it was a triumph. Spirits were high as the curtain came down at about nine thirty, the applause was long and loud, and Hockney was beside himself with excitement. “At the end,” George Lawson recalls, “David came up to me and said, ‘Well, George, what did you think of my opera?’ I replied, ‘Well, David the music is so wonderful,’ and I just shut my eyes. He loved that and I heard him going round saying, ‘Did you hear what George said?’ ”71 At that point the party was by no means over. There was still so much food and drink it was decided to invite the whole company to join the celebrations. Even the few stragglers left from the audience, who were quite bemused coming upon the scene, joined in and as the sun set everyone got stuck into the banquet as if they’d never seen such a spread in all their lives. It made Hockney the hero of the company for weeks after. “So we watched the sun setting,” he remembers, “and then the moon came up so bright that it cast shadows on the lawn. We were there till after midnight, when we took it all away, back on the bus, and there was more champagne on the bus, and even buckets for people to throw up in. Peter had just assumed quite rightly that people would be in that state. We got back to Odin’s about 3 a.m., where there were waiters with more champagne on trays.”72

Only one person missed this great event, and that was Mo McDermott, who was in a drying-out clinic. He wasn’t forgotten, however—Hockney made sure that his name was on the drop curtain along with those of the composer, the librettists, the director and himself.

The reviews for The Rake’s Progress were mixed. William Mann, writing in The Times, thought it “more Hockney than Hogarth,” but considered his approach “even while stealing prime attention … well suited to the icy artificiality and mannered wit of the Auden–Kallman libretto and the emotional pendulum of Stravinsky’s music; and it makes an ideal background for John Cox’s scrupulously characterized and timed production.”73 The New Statesman’s critic, Bayan Northcott, found it “very good indeed. In his own butterfly way, David Hockney … slants the given rather than inventing from scratch. Almost every detail of his sets and costumes can be found somewhere in Hogarth’s engravings, a medium further evoked in the printer’s ink colours and ubiquitous cross-hatchings—even down to the wigs.” He ended his review with the words “Stravinsky would surely have approved.”74

Rodney Milne, however, writing in the Spectator, hated it, and began his review: “By the end of the evening I was so out of sympathy with the new production of The Rake’s Progress…that I asked my Aunt Jennifer, who came as my guest, to write the notice.”75 There followed a pastiche review by this imaginary aunt. “It was a lovely warm evening as we motored down, and we arrived in good time to walk round the gardens, which were looking simply gorgeous. It was Midsummer’s Night, of course, and one half expected to see fairies popping out of their little holes and gambolling around the shrubbery. I was terribly excited to see so many people from that picture about David Hockney … I recognized that nice-looking Peter Something-or-other, the co-star, wearing a white suit … there was Celia Birtwistle looking radiant (I’m told she absolutely loved the opera)…Then there was that New York art dealer with the beard, Henry Kissinger, I think … and Udo Keir, who is the new Warhol superstar … Just before we went in, we passed a pretty gel who seemed a bit under the weather. Someone thought she’d tripped over, but I expect she’d taken something that didn’t agree with her … Rodney says I must mention the opera. He thinks it’s a precious pastiche, as pointless as it is puerile, but he will get carried away with alliteration.”76

Though the early performances of The Rake’s Progress were slow to sell out, it wasn’t long before it became the hottest ticket of the season. Hockney felt a little wistful when the first night was over. “I enjoyed it enormously especially the last three weeks,” he wrote to John Cox from Fort William in Scotland, where he had gone for a short holiday with Henry Geldzahler, “watching it all grow and take shape. I loved the performance;—the acting the singing the orchestra, and even my bit … I told you I felt sad last Saturday as for me it had all ended …”77 He did have something to look forward to, however: before the first performance was over, John Cox had already asked if he might be interested in collaborating on a future Magic Flute.

For Hockney, The Rake’s Progress was a dazzling success, opening up a whole new artistic world in which he could employ his talents. More importantly, being able to run riot with his imagination had released him from the rut in which he perceived himself to have got stuck. “Suddenly I realised I’d found a way to move into another area. In a sense I’d broken my previous attitudes about space and naturalism, which had been bogging me down. I’d found areas to step into which were fascinating: the space of the theatre. It also helped that it was a success, both critically and with the audiences … I then went back to Paris and started painting.”78

Hockney returned to Paris on a positive note, with the applause for The Rake’s Progress still ringing in his ears. He felt energized. The trials and tribulations of the previous few years—his break-up with Peter Schlesinger, the problems with Ossie Clark, the spectre of Jack Hazan’s A Bigger Splash, and his struggles with how to move forward in his painting—were behind him. He had a new, happy relationship with Gregory Evans, and his faith in his work had returned: inspired by John Kirby’s eighteenth-century book The Perspective of Architecture, he now started a new picture, Kerby (After Hogarth), in which, for the first time, he played with the idea of reverse perspective. His willingness to experiment with new ideas was undimmed. Ahead lay a time of great excitement.