7.

The Full English

‘It takes some skill to spoil a breakfast – even the English can’t do it.’

– John Kenneth Galbraith

1.

‘I’m sorry, what did you say?’

‘Can I have the full English, please, but with no egg?’

‘No egg? Did you say, “No egg”?’

‘Yes, that’s right.’

‘You want a breakfast, but with no egg?’

‘Yes.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘You realize you can’t have any substitutions?’

‘No, that’s fine. And I’m perfectly happy to pay the full price for the meal. I just don’t really fancy an egg. If you put one on my plate, I’ll leave it and you’ll have to throw it away, and that would be a waste of an egg.’

‘You’re absolutely sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘Um … would you like scrambled eggs instead?’

About fifteen years ago, I realized that whenever I ate breakfast in a café, B&B or hotel I usually left the fried egg untouched on my plate. It’s not that I ‘didn’t like’ eggs – not as such – it’s just that this was a hearty meal that I seldom finished, and the rubbery egg, slick and shiny like a murder suspect about to crack, would be the last thing to go. So, not being a fan of needless waste, I began to ask for breakfast with no egg.

I had no idea what I was letting myself in for.

The most common response is denial. The waitress gives a nervous little laugh when taking the order or, if she’s from another part of Europe, her native accent suddenly becomes thicker and she starts asking you to repeat things more slowly when, a minute ago, she had no trouble at all with the language. Then, when your plate comes back, the egg is there. Because the egg has to be there. The establishment simply cannot conceive of a world where they serve some people breakfast with no eggs. The fabric of the universe would tear. I simply couldn’t have asked for no eggs. She must have imagined it. Even if you see the waitress write, ‘No egg!?’ on her notepad, the plate usually comes back with eggs – the cook naturally assuming that the new girl must have got it wrong.

More than once in a B&B or hotel, after the order had been submitted the person in charge would come over to the table, introduce themselves and ask, ‘Are you the No Egg People?’ before nervously enquiring whether there was a problem with anything else about our stay. In one country house hotel, minutes after I’d ordered, the chef stomped angrily out of the kitchen in his greasy whites and asked the waitress something. She pointed at me and they both stared, shocked, before he disappeared back into the kitchen to plate me up an eggless breakfast.

When I ate in cafés, as opposed to hotels and restaurants, I began looking for eggless options in the set breakfasts and discovered that there were none. Anywhere. Go – if you really have to – to Burger King, where you can have an egg muffin, a sausage-and-egg muffin, a bacon-and-egg muffin, or a bacon, sausage and egg muffin. Once, when I was in a rush, I ordered a sausage-and-egg muffin, planning on taking out the egg once I was sitting down, and was told I would have to wait because they’d briefly run out of eggs. Delighted, I said I’d just take the sausage muffin. But they refused and made me wait for the egg so that I could throw it away.

Liz and I have simply given in now. We don’t want any trouble. But my friend Chris really doesn’t like eggs and, to this day, breakfast for him is a source of anxiety and conflict. We once shared a flat in Battersea and, not long after we moved in, we decided to check out our local café. We went through the usual rigmarole of attempting to convince the staff to serve us breakfast with no eggs and, amid an atmosphere of increasing hostility, we eventually succeeded. But when Chris got his plate it was also missing the slice of fried bread he’d been looking forward to.

‘Excuse me, there’s no fried slice!’ he called over to the kitchen.

The tension that had been building since we first uttered the words ‘No egg’ reached flashpoint.

‘BUT YOU SAID YOU DIDN’T WANT AN EGG!’ roared the cook.

‘I don’t. But I do want a fried slice. What’s the problem with that?’ asked Chris.

The problem, we figured out, is that the speciality of this café was to serve the fried egg on top of the fried slice. The cook could just about cope with the idea of someone sullying his breakfast plate by asking for no egg. But the idea of the fried egg and fried slice being two separate components, able to exist and be enjoyed individually, was too much for him. We were lucky to get out of there without being physically attacked, and never dared go back. We moved out of the area as soon as our lease permitted. I think it was that experience which finally broke my no-egg resistance. Fine, let them throw their precious egg in the bin after they collected my plate. Chris now fights alone, the last man standing in an eggy Invasion of the Body Snatchers-style dystopia.

I can’t be convinced it’s because the nation adores eggs more than any other ingredient. And yet we eat an estimated 35 million eggs in Britain every day. They can’t all be being forced on people who don’t want them. So why do they dominate the breakfast menu to such an extraordinary extent?

Until the middle of the twentieth century, it was common for households in Britain to keep a few chickens. During the Second World War, animal feed became much scarcer and there was a dramatic reduction in the number of chickens being kept for laying. Numbers took so long to recover that egg rationing stayed in place until 1953. When rationing ended the market failed to pick up – people had got out of the egg habit. So, in 1956, the British government set up the Egg Marketing Board. Over the next few decades, the board ran (with the help of a young advertising executive called Fay Weldon) a multimillion-pound advertising campaign with the strapline ‘Go to work on an egg’, which ran on TV from 1967 until 1971 and instilled in the British consciousness the facts that eggs were cheap, easy to prepare, infinitely flexible and full of protein. The slogan survived in some form or other until 2007, when British advertising authorities banned it for failing to promote a balanced diet – which may seem a curious decision when the alternative of sugary cereal was being advertised directly to children, but the cereal adverts always said, ‘When enjoyed as part of a balanced diet’ at the end, which magically stops them from being bad for children, so that’s OK.

More than that, eggs have always been important to us. In prehistory, we took them from the nests of the red junglefowl, the wild bird that was later bred and domesticated to give us the chicken. We first domesticated chickens not for their flesh but for their eggs, and for the enormous entertainment of making cockerels fight each other to the death. Throughout history, wherever they’ve been enjoyed, the male chicken – or ‘cock’ – has been associated with strength, virility and masculine aggression, while the eggs laid by the female have taken on a vital symbolism. As eggs are so obviously a stage in new life, they’ve been associated with fertility, rebirth, immortality and even divining the future, for at least as long as chickens have been domesticated. There’s a Hindu creation myth that the world itself was born from an egg. Within the Christian tradition eggs are associated with Easter as a symbol of rebirth, with Christ’s emergence from the tomb supposedly being like a chick breaking its thin shell, according to certain evangelical corners of the internet. On a practical level, their consumption was forbidden during Lent, so Easter was a time to joyfully reintroduce them to the diet. There’s a widespread belief that the word ‘Easter’ derives from the celebration of a pagan goddess called Ēostre or Ostara, who was associated with both eggs and hares (hence the bunnies), but there’s little, if any, evidence of such a deity being worshipped. More likely, the egg as a symbol of new life would always have had great significance around the time of year when the days are getting longer and the sun returns in the east.

Whether or not we solidify our sentiments towards eggs into a coherent religious belief – like so much egg white emerging into corporeality from something runny and transparent – we do all carry these latent feelings around with us. Eggs attained magical symbolism wherever they were produced, independently of anywhere else. Like any other religious or spiritual belief, people only have to think it in large enough numbers for it to become ‘true’. So it’s tempting to suggest that eggs are such an important breakfast food because each new morning is a sort of rebirth, the bright yellow yolk of a fried egg symbolizing the sun climbing in its pale, greasy sky – at least if you have it ‘sunny side up’.

But the more likely answer is their practical usefulness. Mornings are all about speed and eggs are quick and easy to cook in a whole number of different ways. We have settled on fried, poached, scrambled or boiled where breakfast is concerned – the latter even being a breakfast all on its own, or perhaps flanked by a regiment of soldiers.

But still, when you think of the English breakfast it’s not defined by eggs but by their other half: the horse to their carriage, the yin to their yang, the PJ to their Duncan – the Vegetarian Killer.

Pigs have been widely kept throughout Britain since Roman times. The French may refer to us as les Rosbifs, but if they were going to be historically accurate, they should be calling us les Porcbouillis. Pigs were easier and cheaper to keep than cows because they could be herded in the forests that once covered Britain and fed on acorns to give their flesh a fine flavour. Or if there were no acorns, they could be fed cheaply on refuse rather than needing rich pasture. Pigs were reared throughout the year and slaughtered at the onset of winter, in a festive orgy of eating, slicing, curing and smoking that ensured ‘everything except the squeak’ was used. Big sides or ‘flitches’ of ham were smoked and salted, the blood was boiled into black pudding and whatever couldn’t be preserved whole was ground and encased in intestines to make sausages. The word ‘bacon’ originally referred to pork in general but eventually came to be associated specifically with the back or belly of the animal when salted, smoked or both. In Henry IV, Part 1, during a robbery Falstaff refers to the villains as ‘bacon-fed knaves’ and urges them into action with a cry of ‘On, bacons, on!’ – another example of food being used as a derogatory identifying nickname. Later, pigs such as the Tamworth, Large White and Oxford Sandy and Black were bred to produce superior bacon, all of which made it mystifying to me that we’ve spent a long time being convinced by supermarkets and advertisers that we should be buying Danish bacon – until I found out why.

Danish bacon imports stretch back to the mid-nineteenth century. The Danes have long had an efficient, centralized pig-farming industry (today, the number of pigs slaughtered every year is five times higher than the Danish population) and used to export most of it to Germany. After the Germans erected trade barriers in 1879 and then banned imports of live pigs altogether in 1887, the Danes desperately looked for an alternative market and found Britain ready and waiting. Population growth following the Industrial Revolution meant Britain was no longer self-sufficient in food, and urbanization had separated most people from the means to produce their own, so the family pig became a distant memory on the smog-filled city streets. Danish bacon imports made bacon so affordable that a working-class family on average wages could eat it two to three times a week.

And so, bacon and eggs became a British national dish. We’ve adorned the plate with other stuff, but this is the heart of the great British breakfast, the foundation that gets us through the day.

It is, without doubt, a successful combination. But each works on its own. On one side, you have omelettes and boiled eggs with soldiers. On the other, you have the mighty bacon sandwich – the distillation of the English breakfast, the best thing on the plate, so perfect, so unimpeachable, that it often makes those lists of favourite meals and national icons all on its own.

Ever since Lurpak butter ran an advertising campaign in the noughties that used heroic, hyperbolic language to celebrate home cooking (that used a lot of butter), every two-bit railway-station forecourt franchise has started spewing out posters along the lines of ‘There is no morning the bacon roll cannot conquer’, like photocopies losing definition with each generation.

It’s the combination of simplicity and flavour that makes the bacon roll, sandwich or buttie so perfect. If you can slice bread and fry strips of meat in a pan till they’re done to your liking, you can make one of the best meals in the world.

But even the simplest meal can be rendered more complex. In 2007, the Danish Bacon and Meat Council commissioned researchers at Leeds University to work out the formula for the perfect bacon sandwich. The researchers spent more than 1,000 hours testing 700 variants before literally delivering the formula for the one buttie to rule them all. And here it is:

N = C + {fb(cm) · fb(tc)} + fb(Ts) + fc · ta

(where N is force in newtons; C is the breaking strain in newtons of uncooked bacon; fb is the function of the bacon type; cm is the cooking method; tc is the cooking time; Ts is the serving temperature; fc is the function of the condiment or filling effect; and ta is the time taken to insert the condiment or filling).

‘We often think that it’s the taste and smell of bacon that consumers find most attractive,’ said Dr Graham Clayton, who led the research. ‘But our research proves that texture and sound is just, if not more, important.’

Fine. But your perfect bacon sandwich might be my idea of hell, with radically different values for tc, fc and especially fb. For example, you might mistakenly believe that bacon should be served crispy or, worse, you might be one of those bizarre freaks who prefers sandwich bacon to be streaky rather than back. But the biggest omission – after all those hours of research – is that the role of the bread hasn’t even been considered.

For me, there are two legitimate approaches to the perfect bacon sandwich. Option 1: a soft, fluffy white roll, sliced in half, with two or three rashers of thick-cut smoked back bacon placed in the middle, seasoned generously with brown sauce. The roll doesn’t even need to be buttered (sorry, Lurpak) if the bacon has been left pink and pliant rather than burnt to death and the brown sauce has been applied liberally up to and not beyond the point where it will squirt out and run down your fingers when you take a bite. Nothing compares. Nothing could be simpler.

Option 2: still pretty damn fine, is the toasted bacon sandwich, with slices of white bread. This tends to be my modern-day café version, because café bread rolls in London can be disappointing, whereas you know what you’re getting with toasted white industrial bread. I suppose the untoasted version is acceptable at a push, if the bread is white and pillowy and the sauce bountiful, but the toasted version is better. The bread should be crispier than the bacon but should still retain a little chewiness.

The fresh, fluffy bacon roll is cheerful and gregarious. The toasted bacon sandwich is somehow a little more thoughtful and serious. And these are the only options you need. Neither option is difficult to achieve even for someone on their first day in the job. There doesn’t have to be any complication.

And yet chain cafés still somehow manage to screw it up, because they feel they have to be different, for the sake of it. This is just one example of Britain’s food-identity crisis, the sense that anything British must somehow be inferior to something foreign, even when this is evidently not true. At the time of writing, Pret A Manger’s ‘bacon roll’ is in fact a ‘bacon brioche’, served ‘with a dab of unmistakably French butter’. Why would anyone do that? The French don’t do bacon rolls. The English do. So who on earth would think a French-style bacon roll would be an improvement on the original, apart from someone who hates this country and everyone who lives in it, possibly including themselves? I have no idea what your issues are, and I wish you well in resolving them, but for all our sakes, don’t bring the bacon roll into it.

I always used to think that my ardour for the bacon buttie was in line with that of the nation as a whole. But over recent years I’ve noticed that they’re a bit of a compulsion. When I judge beer and cider competitions we tend to start first thing in the morning, when the palate is still fresh. Sometimes the organizers will put out platters of bacon sandwiches, with bowls of ketchup and brown sauce on the side. The sight of them sends me crazy. I always eat as many as I can, stopping only when I think other people might notice. If I’m travelling mid-morning and I pass a place that looks like it might do a half-decent one, I’ll grab one even if I’ve already had breakfast, even if I’m not remotely hungry, even if my original breakfast was also a bacon roll! Until I started writing this book I had always supposed I just really, really liked bacon sandwiches. And then I remembered something that had been buried away for a very long time.

We never had bacon at home when I was young. If you’re eating bacon regularly, you’re almost certainly having it for breakfast, which means cooking first thing in the morning, and no one in our house ever did that. Every single morning throughout my childhood was either cereal or toast, eaten alone – except for when we went on holiday.

For most of my childhood my dad worked nights and we didn’t see much of him. The regular shift was 10 p.m. till 6 a.m. and, if he could get the overtime, it would be 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. I’d be woken every morning by the sound of Dad’s Skoda pulling into the drive at around six twenty and then hear him potter for a bit before getting me up for my paper round at seven. He’d get us ready for school and, once we were out of the door and my mum was at work, he’d go to bed. We’d see him again for about forty-five minutes in the evening, when he got up and ate dinner before going back to work. If he could, he’d work weekends as well, switching to the day shift and doing 10 a.m. till 6 p.m. or, if he could, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. Somehow, it seemed we always needed the money. But as a kid, it also felt like he didn’t really want to be with us. The only time we got to see him properly was on our holidays – but these also stopped some time in my mid-teens, amid excuses that seemed to make sense at the time.

For a few years before then we owned a static caravan at the Lincolnshire coastal resort of Mablethorpe, which is a bit like neighbouring Cleethorpes, only without the glamour. Every morning, around seven o’clock, my dad would wake me just like he did for my paper round, so that we could walk the dog together.fn1 He would wake me as quietly as possible – just me – and we wouldn’t speak until we were outside the caravan, so as not to wake my mum or my brother. Even when we were on our way, we still didn’t say much. We just walked a mile or so up the beach and got to a little food van just as it was opening up for the day. Dad bought us white, fluffy bacon rolls – the type I still regard as superior today – and Styrofoam cups of tea and we’d walk back down the flat, wet beach, not saying much, just enjoying breakfast and watching the dog on her intrepid adventures.

My dad died when I was twenty-seven. About ten years later, I had one of those rare, lucid dreams where you’re clearly inside the dream but you feel fully awake and can act and move freely rather than being controlled by dream logic. I was my grown-up self, wearing the clothes I’d worn that day, and next to me was my dad. He looked to be in his late fifties, around the age he was when he died, but with no signs of illness other than the habitual stoop from his eternally bad back. We were walking down that beach at Mablethorpe with Mitzi at our feet and bacon rolls in our hands. This time, we talked. We talked for a long time.

I said all the things I hadn’t been able to say to him as he lay dying, as my mum tearfully begged me to say something, anything, just in case he could still hear us, just in case simply letting him know we were there might give him some comfort. I said everything I couldn’t say to him six months previously, when he told me he always guessed the fags would get him eventually but he’d hoped for a few more years. We spoke openly and freely, like mates. We even laughed together, somehow sharing the same understanding, worldview and sense of humour, in a way we never did when he was alive. I could smell the ozone and hear the invisible sea beyond the mist. And I could taste the bacon roll.

So yeah, maybe I like bacon rolls a little more than most people.

2.

Last time I was in Amsterdam I decided to go to a café for an ‘English breakfast’ to see what it was like. I came to regret this decision. They must have seen a photo of a real English breakfast and tried to re-create it from that alone, without any real-life experience of what it entailed, like some kind of Dutch Anglophile cargo cult. It consisted of a large mound of very pink, very cold shavings of streaky bacon, two sinister-looking cocktail sausages, a pulverized fried egg with green bits in it, a quarter of a raw tomato, some mushrooms and half an acre of lukewarm baked beans. We might complain that our curries and spag bol are travesties of the originals, but it works both ways: if this is what our European neighbours think an English breakfast is, no wonder British food has such a dire reputation.

Bacon and eggs (and sausages and black pudding, if you’ve slaughtered your pig properly) have been food since at least Anglo-Saxon times. But they only became breakfast cuisine in the nineteenth century. And even more curiously, while bacon and eggs are freely available across Europe, they only became cooked breakfast – in the way we know it – in Britain (and, in the early twentieth century, thanks to a focused advertising campaign, in North America). Cold cuts of ham may be common across Europe, but that’s different. And while eggs appear in many Mediterranean breakfast dishes, they manifest in completely different ways. In The English Breakfast, Kaori O’Connor suggests that cuisines don’t recognize national borders. This is why the continental breakfast is, with a few tweaks here and there, ‘continental’ rather than simply ‘French’. It’s why a breakfast dish based on a pan of cooked tomatoes (and sometimes peppers) with eggs cracked into it spreads around the entire coastline of the Mediterranean with minimal variations, even if it’s called menemen in Turkey, shakshuka in Tunisia and huevos a la flamenca in Spain. But Britain and Japan, as islands, retain a separateness. The full English breakfast is triumphant at home, a national icon, but it hasn’t prospered elsewhere in anything like the same form. There are few better examples of the difference between the biological reality of ‘food’ and the ideological construct of ‘cuisine’. The story of how these food items became a national breakfast unique to Britain is one that’s linked more directly and explicitly to the definition of our national identity than any meal we’ve looked at so far.

The traditional full English in all its stodgy glory is today a distinctly working-class meal, associated with labourers eating in ‘greasy spoon’ cafés, while office workers nibble pastries in continental-style cafés next door. While builders and scaffolders are scoffing calorific breakfasts to fuel them for the physical work that lies ahead, washing them down with the beverage middle-class people refer to as ‘builder’s tea’, the office worker is doing something similar with their coffee – stockpiling alertness and mental energy to cope with whatever the day is about to throw at them.

Builders just refer to builder’s tea as ‘tea’. But middle-class people offer it and ask for it in tones of cheeky irony. By calling it builder’s tea, we’re acknowledging that we’re familiar with and often drink a whole array of different teas, unlike builders, who only drink one kind because that’s all they know. But we’re also saying that, right now, we’re feeling kinda unpretentious and down to earth, just regular guys.

So it’s satisfying to discover that of all the different blends of tea available, the full-bodied, black, tea-heavy blend that came to dominate British working-class culture originated in Scotland and found its popularity when Queen Victoria declared it her favourite.

In the eighteenth century, when tea was still an expensive luxury available only to the wealthy, it changed the shape of a typical society day in more ways than one. As well as afternoon tea, some ladies began to hold breakfast parties, offering tea along with bread, butter, jam and, later, two more exotic new imports: coffee and chocolate. This did come with some practical headaches. Great houses would often be very cold overnight and it would take time in the mornings for fires to be lit and for everything to warm up. Butter – another luxury – was therefore often far too cold to spread properly at breakfast. The delightfully sociable solution was to huddle around the freshly lit fire with toasting forks. The German traveller Carl Philip Moritz was thrilled to discover this innovation during a walking tour of England in 1782: ‘There is a way of roasting slices of buttered bread before the fire which is incomparable,’ he wrote. ‘One slice after another is taken and held to the fire with a fork till the butter soaks through the whole pile of slices. This is called toast.’

Before this point, breakfast simply hadn’t been a thing. The earliest English cookbooks are full of recipes for large main meals later in the day but offer none for breakfast. It starts to get a few mentions in the fifteenth century but, in 1478, the household ordinances of King Edward IV stipulated that only members of the royal household down to the rank of squire could eat it and, even then, it was a simple affair of bread, cheese and ale, boiled meat or fish and eggs (obviously) on meat-free days. It was essentially a primitive version of the ‘continental breakfast’ that’s still eaten today across the rest of Europe. But in the nineteenth century that would change.

The Industrial Revolution altered the way time was perceived. Work had been tied to the rhythms of nature, happened when things needed doing and largely depended on natural light. The employment of machines meant that people moved from the land to towns and cities and working hours were straightened out and extended.

For centuries, the landed gentry of England had been the voice and tone of the nation. Peasants worked on their land and, between the gentry and the peasants, free yeomen, who enjoyed decent home comforts and perhaps a little land of their own, kept everything running. Food was hearty and unpretentious, the bounty of the land, and therefore an indicator of the status and standards of the gentry who owned that land. The social order of England was fixed, changing little over the years.

Then, suddenly, the peasants were moving off the land and into factories and mills. In towns and cities a new, commercially minded middle class was aspiring to the status of the gentry. The gentry had always been suspicious of cities, especially the capital. Ever since Charles II returned from his exile in the French court of his first cousin Louis XIV, French habits and tastes were slavishly followed by large sections of the nobility. The gentry had always stood for what they regarded as stolid, plain Englishness. Now, with their land emptying and its value falling, the balance of power was moving to the cosmopolitan city. They feared that foreign influences and imported goods – especially foreign food, which was invariably referred to as ‘French food’, regardless of where it had come from – was threatening the moral fibre of the nation itself. When England lost its American colonies and the French Revolution raged, there arose a nostalgia for a more secure and knowable past, a yearning for tradition – a desire to Take Back Control and Make Britain Great Again, if you can imagine such a thing.

The answer lay in the land itself and in the produce that came from it. Old Anglo-Saxon was regarded as the ‘true’ version of Englishness – before the Normans came over here and ruined everything – and a huge part of Anglo-Saxon culture had been the notion of feasting and hospitality. Rural landowners welcomed house guests to parties that were several days long and breakfast became a defining feature of these events. French cookbooks were full of recipes for lunch and dinner that had come to dominate upper-class English cuisine too. But as a means of class and national expression, breakfast was virgin territory.

Served between nine and eleven, breakfast was the only meal of the day where people helped themselves, without servants in attendance. Guests were free to stop by whenever they felt like it and it was customary to go out walking or hunting first to work up an appetite. This was the most informal meal of the day. A plethora of hot and cold dishes was arrayed on the sideboard and guests served themselves. They could choose eggs, bacon, sausages, devilled kidneys and fish such as haddock from the hot selection, shored up with ham, tongue, beef and cold roast partridge, pheasant or grouse (when they were in season) from the cold table. Forget the Lurpak ads and their derivatives: this truly was the breakfast of champions – even if, today, we would call it brunch.

Part of the appeal of the great country-house sideboard breakfast was what it said about you if you could attend. The lower and middle classes had to rise early and go to work, grabbing whatever they could along the way. The gentry and their guests were demonstrating that they had the wherewithal to lay on a sumptuous feast first thing in the morning (which, in reality, meant they had servants rising at 5 a.m. to prepare it), as well as the leisure to sit and graze all morning, because there was nothing urgent to be done.

But as the swing towards urbanization continued, for most, this lifestyle couldn’t last. As the gentry joined the aspiring urban middle classes in going out to work each morning, a good breakfast was seen as essential preparation for the day. Even in a much-reduced form, both practically and symbolically breakfast echoed the age of the great country houses and became a standard of morally upstanding Englishness. In 1861, the first edition of Isabella Beeton’s Book of Household Management contained a mere two sentences on the subject of breakfast. The next edition, in 1888, had an entire chapter, including menus and table settings. It was competing against a slew of books full of breakfast recipes, aimed at people who knew they needed to keep up with fashion but had no idea how to prepare a meal that, as far as most were concerned, hadn’t really existed a few years before.

3.

The country-house breakfast sideboard survives today, much reduced, as the most expensive and, often, the most disappointing iteration of the English breakfast you’re likely to find.

As part of my job, there’s rarely a week goes by without my spending at least one night in a hotel or B&B somewhere around the UK. On the morning I’m writing this, I’m in a chain business hotel in a large English city. The restaurant is busy for breakfast and, as is often the case, once I’ve been seated and asked whether I’d like tea or coffee, I’m invited to help myself to the buffet.

The principle is exactly the same as the Victorian country-house sideboard but the contents are quite different. There are no fish rissoles, kidneys or game pie. There aren’t even pears or oranges. There are, of course, little packets of Kellogg’s breakfast cereal, pots of fruity yoghurt and a variety of continental pastries. But taking up most of the space is a line of silver tureens and white serving dishes containing the makings of the traditional cooked breakfast.

Sometimes, hotels like this have great reputations. The rooms are stylishly designed and full of plump pillows and pampering toiletries, maybe even fluffy white robes and slippers and the temptation of a well-stocked mini-bar. Other times there are a few teabags and sachets of Nescafé and a kettle that won’t fit under the bathroom tap and therefore has to be filled with water one flimsy plastic tumbler at a time. But whatever the rest of the hotel is like, nine times out of ten, the cooked breakfast is remarkably consistent.

Like today, no matter what time you arrive, the tureens and serving plates are almost empty, their puddles of grease reflecting the ‘hot’ lamps that gaze down like baleful, yellow eyes without actually doing anything. There are a few strips of emaciated bacon flecked with congealed white, greasy water, sweaty sausages with the consistency and mouthfeel of cold mashed potato, rubbery eggs, mushrooms from a tin, hash browns out of a packet from the local branch of Iceland, tomatoes that seem not so much cooked as mummified and baked beans that have simply surrendered. All of it sits waiting, flaccid and melancholic, causing even the hungriest soul to be suddenly struck with an overwhelming sense of ennui. You ask yourself if you can be bothered to eat this. Wouldn’t it just be less hassle to die of starvation? Why are you even looking at it when, if you were at home today, you’d probably just have yoghurt and fruit and a cup of tea, maybe a slice of toast? And then you remember that, whatever you choose to eat, this breakfast is going to cost you EIGHTEEN FUCKING QUID, so you fill a plate and smother the whole lot in brown sauce to try to make it edible.

This parody of the English breakfast reflects perfectly a peculiar and depressing quirk of British commerce. Business travellers have put up with this soulless version of breakfast for years. And then, in the 1990s, one new hotel chain changed the game. Malmaison, the first British ‘design hotel’, did something no other mid-market hotel chain had thought of doing for decades: they decided to make everything just a little bit nicer than it absolutely had to be for the prices they were charging. The rooms were stylishly designed, the staff were friendlier, the beds were more comfortable.

And the breakfast was amazing.

Thick, proper butcher’s sausages, your choice of fresh eggs, succulent mushrooms and juicy tomatoes, all cooked fresh to order rather than slowly expiring on a lukewarm buffet counter. It was the first time I’d really looked at a cooked hotel breakfast and thought properly about what was on the plate. Until then, sausages had been Wall’s bangers, pale and wan, sticky rather than greasy. Bacon was just bacon. Now, each ingredient had a story to tell.

You paid extra for it, of course: the first time I stayed in a Malmaison, around 1995, a typical hotel buffet breakfast was about £8. Malmaison, in line with its superior quality, charged closer to £12. But you didn’t mind because the quality was so much better.

Other hotel chains could have reacted to this by looking at their own breakfasts and saying, ‘Hmm … we really could do better than this. I wonder where the Mal sources its lovely sausages from?’ Instead, they seem to have said, ‘Hey, Malmaison is charging twelve quid for their breakfast and we’re only charging eight. Obviously, our breakfast is awful compared to theirs, so there’s no way we could charge the same as them. But we could bump up the price to a tenner without doing anything else and we’d still be cheaper.’ So the tide of all breakfast prices rises, brands like Malmaison realize they can charge even more because they’re still so much better, the other chains raise their prices to match, and suddenly you’re paying nearly twenty quid for a bowl of cornflakes and a cup of tea and breakfast has become the most expensive dish the restaurant serves.

It’s a common pattern. Around the same time Malmaison shook up hotel dining, the gastropub arrived in affluent urban areas to give traditional pub grub a kicking. Instead of offering a limp, frozen burger patty served with oven chips for a fiver, the gastropub introduced burgers that were home-made, thick and juicy, with chunky chips that were no doubt hand-cut and triple-fried, served it on a massive white plate with a sprinkle of parsley and charged a tenner. The traditional boozer knew what to do: serve the same old, limp burger and oven chips on a big new white plate with a sprinkle of parsley and put the price up to eight quid.

It doesn’t have to be like this. We don’t have to sit back and accept it. But in corporate Britain we march in time and force it down, without enthusiasm or enjoyment, never stopping to ask why.

4.

There’s no such thing as the full British breakfast. While the English have always had a tendency to conflate ‘English’ and ‘British’, this is still strange because, by the time the English breakfast came on the scene, England was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The cooked breakfast is eaten in every part of the United Kingdom, but the English have always claimed it as theirs alone.

It’s therefore unsurprising – and entirely fair – that the other home nations insist on defining their own specific alternatives to the English breakfast, which are, naturally, very different. All variations tend to have bacon and some other ingredients in common – of course they do – and all must be accompanied by breakfast tea. These are the essentials.

Building on this foundation, the Welsh breakfast takes a creative turn. Tea washes down a plate of bacon, cockles, laverbread and fried bread. Wales has 1,200 miles of coastline and, at its industrial peak, women and children would forage for cockles and laver, a type of seaweed that’s boiled and minced to create laverbread, a gooey substance that Richard Burton dubbed ‘Welshman’s caviar’. This cheap, highly nutritious food was vital sustenance for miners and factory workers in the nineteenth century.

Scotland also enhanced its breakfast by looking to the sea, building a reputation that prompted Samuel Johnson to declare, ‘If an epicure could move by a wish in quest of sensual gratification, wherever he had supped, he would breakfast in Scotland.’ Ayrshire bacon and Stornoway black pudding gives a solid meaty core, but this is supported by the option of smoked fish such as Finnan haddock or kippered herring, as well as tattie scones, oatcakes and porridge. Scotland’s facility with cereals such as oats also helped Stornoway black pudding become widely regarded as the best in the world. In May 2013, it was granted PGI status by the European Union; now, only black pudding made with specific proportions of beef suet, oatmeal, onion and blood on the Isle of Lewis or in the surrounding Stornoway Trust area can be called Stornoway black pudding.

Johnson aside, the Scottish and Welsh breakfasts really don’t get the recognition they deserve as entities in their own right rather than slight variations on the English breakfast. But they each get a lot more than the poor old Ulster fry.

If you don’t know Northern Ireland well, it’s impossible to appreciate just how widespread the effect of the conflict known so euphemistically as ‘The Troubles’ was. Fear, suspicion and division affected every aspect of daily life, from the brand of crisps you bought to whether it was a good idea to go to the pub or not. To the outside world, the conflict was Northern Ireland’s identity, and in England we rarely heard anything else about the place or its people.

Now, twenty years after the Good Friday Agreement came into effect, Northern Ireland is finding its voice and flexing its muscles. I first became aware of it while judging the Great Taste Awards and learning that a disproportionate number of the ciders we blind-tasted and gave the highest marks to were from Northern Irish producers. I then learned that their fellow butchers and bakers were sweeping the board too. I ended up touring the province for a long weekend, during which I ate and drink so much wonderful stuff I started to answer to the name Mr Creosote.

The Ulster fry at Newforge House, County Armagh, is considered to be the best in Northern Ireland. When I was staying here after visiting the cider-makers I had to leave for the airport before breakfast was served, and I wouldn’t have been able to touch it anyway because dinner the night before had ensured I didn’t feel hungry again until the following Wednesday. So I’ve come back again specially to try it.

The composition of the plate is visually stunning, so elegant you have to do a double-take to check that this really is a fried breakfast. That might make it sound pretentious, but it’s beauty is its simple elegance. A single thick-cut rasher of back bacon and a fat pork sausage lie spooning each other, like giant, meaty quotation marks, at the top of my plate – at twelve o’clock from where I’m sitting. Between two and six o’clock a soda farl, a Scotch pancake and a slice of potato bread lie fanned like a magician’s cards. A perfect poached egg, fluffy like a dollop of freshly made cream cheese, glows at seven o’clock and completing the clock face are two elegant discs of black and white pudding. Three roasted cherry tomatoes, still on the vine, sit on top of this, a concession to vegetables that’s little more than a garnish.

As I’m photographing my breakfast and scribbling notes, the Irish brewers I’m breakfasting with nod at their plates approvingly. Then one of them leans over to me and says in a low voice, ‘I hear the English have beans on their breakfasts. What’s going on there? And sometimes even mushrooms?’ I nod, suddenly apologetic, as he stares back at his plate, trying to imagine such horrors upon it.

John Mathers is the owner of Newforge House and the creator of our breakfast. I’m sure he could afford to hire a talented cook but breakfast is the signature of the place and he loves doing it himself.

‘It’s straightforward, really, it’s just about good ingredients,’ he says. ‘Take sausages. I don’t want a silly sausage, just pork – nicely spiced, but simple. I do one slice of bacon, but there’s no rubbish in it, no injections, so it crisps up nicely. If it’s this good, you don’t need more than one slice. Then there’s the black pudding, which should be dry and spicy but not crumbly. But in Northern Ireland it’s all about the breads. There’s a great tradition of non-yeast baking here. I get my breads from a local bakery, lightly butter them and fry them in a dry pan. We have our own chickens and we offer a choice of scrambled or poached eggs. I prefer poached, because it gives you a bit of sauce. The only controversial thing for me is you’ve got tomato, but you’ve got to be healthy.’

John leaves us to enjoy our food. The potato bread is smooth, creamy and addictive. The bacon tastes of bacon or, rather, like bacon used to taste. It’s the taste of bacon at Mablethorpe in 1981, a taste that’s missing from all the bacon sandwiches I now compulsively eat. The sausage is juicy and sweet. The white pudding is grainy and surprisingly light. It’s a substantial plate of food, but one that encourages you to finish it in business-like fashion. When I do, I feel full, but not bloated.

‘It’s good, but it’s not rarefied,’ says John, as he scoops up our empty plates. ‘People call the Ulster fry a heart attack on a plate, but it doesn’t have to be. Only if it’s bad.’

John’s Ulster fry, as well as Stornoway black pudding, smoked Finnan haddock and Welsh cockles and laverbread, show that the cooked breakfast has always been about making the best of what’s available nearby. The cooked breakfast can be a celebration of local produce and it can be a really good-quality meal. This is not a gentrified breakfast or a breakfast done ‘with a twist’ – no builder would turn up his nose at this plate of food and think it pretentious. It’s just really well done, like the Malmaison breakfast, better than it absolutely needs to be but exactly as good as it should be.

5.

Back in my days working in advertising, I spent a few years at an agency in Dean Street, in the heart of Soho. It was a work-hard, play-hard culture, if your idea of play was to go out drinking until the small hours with people you’ve already spent all day with and stay awake by doing fat lines of cocaine in the toilets. There was a macho culture of presenteeism, where the person who spent the longest time in the office was obviously the best at their job, and anyone who left before 8 p.m. was greeted with a chorus of ‘Cheers, mate! Thanks for popping in.’ It wasn’t unusual to spend eighty hours a week in a building that had no air conditioning and where, if you left the windows open all night, in the morning your desk would be covered by a fine layer of what looked like soot.

Breakfast was provided courtesy of the agency – each floor had a tiny kitchen with a kettle and a toaster, and cheap teabags, white bread, margarine and Nutella. With a sandwich from a nearby shop at lunchtime and pizza ordered in when we worked past 9 p.m., it was often possible to eat every single meal at your desk for almost a week.

Sometimes, shooting out of the Tube into the insanity of Oxford Street at 7.30 a.m., having got home at midnight the night before, I would fantasize about spending a day’s holiday (or ‘annual leave’, as office workers are now supposed to call it, as if they’re in the army or something) taking my usual Tube into town and, instead of going to the office, buying a paper and sitting by the window in a greasy-spoon café, eating breakfast and just watching people barge their way to work. I’d wonder about their stories, study their expressions and congratulate myself on being outside their world, even if just for a day. Then, as the pace slackened, when everyone was at their desks I’d lean back, stretch and plan a day of walking around the city, visiting museums and galleries. Or something. Anything that provided the greatest contrast I could find to sitting in that office for fourteen hours.

I never did this – not once in the twelve years I worked full time in central London offices. I suppose, when I did take holiday days, Soho was the last place I wanted to be. I began working freelance in 2003, gradually shifting the weight of my career from advertising to writing. I write full time these days, but I’ve still never lived out my rush-hour greasy-spoon fantasy. Now, I have to do it. I have to go to a greasy spoon in Soho and enjoy a leisurely breakfast. It’s essential work.

The ‘greasy spoon’ is much loved, especially by the kind of people who drink ‘builder’s tea’. It’s as much a part of our urban fabric as the chippie, curry house or backstreet boozer. In the 1950s, young people began leaving home to find clerical work in cities and would often live in bedsits without the means or knowledge to cook for themselves. Soho in particular was renowned for its bedsit culture and the streets teemed with cheap cafés to cater for it.

Once meant in a derogatory way, the term ‘greasy spoon’, since the kind of café it applies to has started disappearing in the face of soaring rents and chain brand dominance, has been repurposed as a term of affection. Across class barriers, fans who don’t perhaps fit the typical profile of the clientele seem all the more passionate, adoring these places for their architecture, decor and atmosphere as much as the food, and for the unchanging routine they represent, the idea of time out from an increasingly hectic world. The Formica tables, plastic bottles of ketchup and brown sauce, salt and pepper shakers and Pyrex cups and saucers keep alive a mid-twentieth-century image of a Britain that’s as comforting to us today as the ideal of the country-house breakfast was to the nineteenth-century middle classes. There’s been a spate of lovingly written and photographed guides to old-school cafés and many of them mention the Star Café in Soho as a perfect example. Just around the corner from my old work, it’s the obvious choice for my archetypal full English breakfast.

The Star has a reputation for being patronized by film people, including the director Mike Leigh, and as well as the usual set breakfasts it has a massive breakfast known as ‘The Terminator’. A good greasy spoon invariably acquires regulars, just like a pub, and some of them pass into the folklore of the establishment. These are people with sufficient status to ask for something special, whose individual creations are not only tolerated but celebrated. Usually, the named breakfast will be a tribute to a superhuman appetite: Jim’s Special or Bill’s Big Breakfast usually entails at least two of everything.

But not always.

The Star’s menu includes the Tim Mellors Special. Tim Mellors was the creative director at the ad agency around the corner when I worked there. While I was dreaming of my stolen morning watching the world go by, he was in here so often he had his favourite option named after him. The Tim Mellors Special is in fact the Star’s name for smoked salmon and scrambled eggs. Discovering that my former boss was a regular at a greasy-spoon café, keeping it real with the man in the street, but insisted on having smoked salmon and scrambled eggs when he got there, says more about the advertising industry in the 1990s than all the drugs, shit designer clothes and Conran restaurants put together.

Almost twenty years after I last worked with its favoured patron, the Star Café doesn’t seem to be where it’s supposed to be. I find the street no problem, but one side of it and most of the middle has disappeared into a large hole. Walking down the narrow gap left by the hoardings for the interminable Crossrail project, I turn and retrace my steps. There’s obviously no café along this street. I check the street numbers and, when I find 22 Great Chapel Street, I’m saddened but not surprised to discover that what was until recently the Star Café is now the London Gin Club. There’s still a pub-style hanging sign above the door with a Christmas-like star and the words ‘established 1933’, but there’s no other evidence that the Star Café was ever here.

Later, I learn that the Soho Gin Club was founded by Julia, daughter of the Star’s owner, Mario Forte. The Star was founded by Mario’s father in 1933, and Mario worked there from 1958 until he passed away in 2014, when he was sent off with a star-studded Soho funeral. Mario’s final years were blighted by the Crossrail project, which he claimed resulted in a 40 per cent drop in trade. ‘I don’t know how long we’ll be able to continue,’ he said shortly before he died. Julia had launched The Star at Night, a bar upstairs from the café, in the evenings eleven years previously. It makes grim sense that this would be the business to carry on following Mario’s passing.

Thankfully, a short bus ride across town, Andrew’s Café at the bottom of Gray’s Inn Road is still very much open for business. It’s one of three businesses occupying the ground floor of an elegant but shabby 1920s building, the other two being a gift card and printer’s shop and a twenty-four-hour grocery. The building is overshadowed by its more imposing neighbours, and just up the road is the Pentagon-like mass of ITV and Channel 4’s main offices and studios. Andrew’s is famous for counting most of the Channel 4 news team among its regulars, as well as celebrities such as Nigella Lawson and David Walliams.

Inside, the rippled wallpaper seems to retain the memory of decades of nicotine stains. It’s plastered with theatre posters and artful photography of London buses and taxis. Formica-topped tables and chairs with red-padded vinyl seats are welcoming and reassuring. There’s no irony here, no self-mythologizing. It feels like it hasn’t changed since the eponymous Andrew and his brother Lorenzo opened the place in the 1950s. Like Mario Forte’s father and many other entrepreneurs who founded the best of these restaurants, Andrew and Lorenzo were first-generation immigrants from Italy. Opening and working in a restaurant is a relatively easy thing to do for immigrants in a new country, and the Italians were followed by Greeks, Turks and, more recently, Eastern Europeans. The great English breakfast in the celebrated greasy-spoon café is largely the work of ‘foreigners’ and their children.

Like any legendary café, Andrew’s walls boast photos of its famous clientele. But when I look closer, Jon Snow and Krishnan Guru-Murthy don’t look as happy in the pictures as you might expect. I look closer. These press clippings aren’t celebrating the cafe and its patrons. They’re part of a campaign to try to save it from destruction.

The owners of the land want to tear down everything but the façade of this old building and replace it with a much bigger modern complex that will comprise 60,000 square feet of office space, 6,000 square feet of retail space and 15 residential apartments. The café’s current owner, Erdogan Garip, who took over from Andrew in 2003, has organized a petition against the development, which, thanks to his famous customers, garnered widespread press coverage. But at the time of writing, despite this petition, as well as strong objections from Historic England and a grassroots campaign from local residents, Camden Council approved the development plans for this astonishingly ugly and, residents argue, entirely unnecessary development.

A spokesman for developers Dukelease claims, ‘The development is focused on providing flexible space and we do envisage that there will be a café or restaurant included in the proposals. However, our plans haven’t yet been considered by Camden and rental levels are therefore still to be determined.’ In other words, by the time you read this, Andrew’s will probably have been replaced by yet another branch of Costa Coffee.

I’ve always felt more at home in a greasy spoon than I do in a Costa or a Starbucks. I love the sounds of classic-hits radio stations playing over tinny speakers quietly enough so that everyone can still hear themselves speak and the surgically filleted copies of the Sun and the Star lying draped across tables and chairs. If I’m in a place like this early in the morning, every single customer will be male. Apart from me, they’ll all have close-cropped hair and will be wearing jeans, sweatshirts and hoodies. Some of them will sport hi-vis bibs, while others will have slung theirs, along with their hard hats, across the backs of chairs or on the floor beneath the tables. They sit, and read, and eat, with an air of solemnity that always surprises me. These are the lads who are stereotyped in popular culture as wolf-whistling, cat-calling boors when they’re up on the scaffolding. But here in the café, they speak softly and are almost ostentatiously polite to the heavy-accented Turkish or Eastern European women serving their meals. When one of the younger guys attempts a bit of levity, he’ll be gently but firmly silenced by one of the older men. This is a time for preparing for the day ahead. This is breakfast as sacrament.

Andrew’s is open all day, and does roast dinners for £5.90, fresh, filled rolls for less than half the price of their cellophane-wrapped, factory-produced counterparts in big chains and jacket potatoes for under a fiver. A blackboard on one wall offers syrup pudding, sultana pudding, apple pie, cherry pie, jam roll served with custard or ice cream and – on Thursdays only – apple crumble. But the breakfasts are the star, dominating the huge blackboard above the counter. The available options cover most of the board with dense writing that looks more like the workings of a Nobel physicist than a restaurant menu but, to the trained eye, it’s fairly navigable.

There are four main set breakfasts. Set One consists of egg, bacon, sausage, baked beans or tomato, two slices of toast or bread and tea or coffee for £5.20. Set Two removes the option of baked beans – you’re only allowed tomato – and otherwise differs from Set One only in that it also has mushrooms, and for that it’s 70 pence more expensive. Set Three goes the other way, getting rid of the tomato and switching out the mushrooms for chips, while Set Four tears up convention and freestyles, controversially opting for two eggs instead of one, allowing you mushrooms and baked beans, adding black pudding and swapping the toast for a fried slice. The extra egg comes at an extra cost – Set Four is £6.50.

These may be the chosen sets. But none of them, as far as Andrews is concerned, counts as the full English. Maybe they are a full English but they’re not the full English, which has its own separate listing. The same price as Set Four, you get hash browns, mushrooms and beans shoring up the core, and we’re back to two slices of toast or bread.

As if that’s not enough to choose from, there’s also ‘Andrew’s Breakfast’, which loses the hash brown from the full English and adds an extra egg and an extra sausage.

To any of these you can add extra items: £1.50 for extra bacon or sausage, or £1 for extra anything else. But you are rewarded for staying within the prescribed sets. Upgrade from one set to the next and you pay an extra 60 pence or 70 pence. Go off piste, and it’ll cost you at least £1 extra. There are also two vegetarian set breakfasts and a series of ‘toast combinations’. These are clearly aimed at the gullible: Baked Beans on 2 Toast costs £2.70, but ‘2 Toast’ on its own is 90 pence, and baked beans as an extra is, as we’ve established, £1. I wasn’t born yesterday.

To the uninitiated, the menu is a work of daunting complexity in the guise of simple, honest food. Why and how do cafés go to such extraordinary bureaucratic lengths? The answer, as I discovered when I started talking to people about whether an egg was necessary or obligatory, and about whether mushrooms or beans had any rightful place on a breakfast plate, is the simple truth that everyone has their own favourite breakfast items, and that these preferences are hard-wired. This, remember, began life as a meal where people served themselves from platters on a sideboard. Even if we’re unaware of the history of the great country-house breakfast, its legacy means the modern greasy spoon needs to offer as much choice – or illusion of choice – as possible. And from the café’s perspective, it needs to do so while minimizing the dreaded possibility of customer substitutions.

If you’re some noob who orders Set One and asks if you can have mushrooms instead of the sausage, you have no idea of the forces you are playing with. You might think it’s a straightforward request. You might even think you’re being helpful by saying you don’t mind paying the full price for Set One even though, according to the extras list, mushrooms are 50 pence cheaper than the sausage. But you’re ruining everything. The café has gone to Herculean lengths to create its own permutations, which will vary slightly from those offered by any other café, if you look closely enough. The establishment has exhausted itself working out the Byzantine economics of Sets, Deals and Extras. Don’t believe me? Think it’s simple? OK, come on, let’s look at this menu in a little more detail.

Close scrutiny of the various boards and menus at Andrew’s reveals that they have a total of thirteen different ingredients that they use across all their breakfasts. They are: egg, bacon, sausage, beans, mushrooms, black pudding, hash brown, chips, tomato, fried slice, bubble and squeak, onions and burger. Is a burger a legitimate breakfast item? As for chips, we’ll deal with those later. But we are where we are, in Andrew’s, and we’re playing by Andrew’s rules.

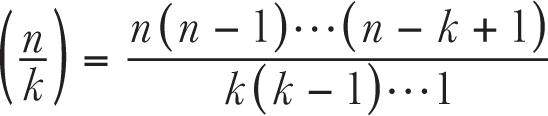

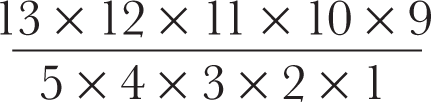

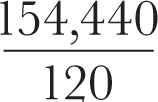

Each of the set breakfasts consists of five or six of these ingredients, which seems like a reasonable number. So how do you work out what to put on each plate? Well, the number of potential different five-ingredient breakfasts that can be made from a list of thirteen ingredients can be calculated using the mathematical formula for combinations. For a set S, where the number of possible breakfast elements is expressed as n, and the subset – the number of ingredients on our breakfast plate – is k, we can work out how many different five-item breakfasts it’s possible to create by using the formula:

This may look complicated, but it’s a neater way of writing down what you actually have to do to work out the answer, which – with thirteen possible ingredients going on to a five-item plate – is:

This works out as:

which gives you a possible 1,287 different five-ingredient set-breakfast combinations from those seemingly harmless thirteen ingredients. That means you could have a different breakfast every single day for over three and a half years and still not quite get through them all.

This is before you even get into multiples of each individual ingredient or consider that there’s another big number of possible six- or seven-ingredient breakfasts (1,716 each) to throw into the mix.

And so, finally, I have my answer to why eggs are so ubiquitous. Forget convenience. Forget religious symbolism. If you simply decree that every single five-ingredient breakfast must contain a fried egg, at a stroke you reduce the number of possible combinations from 1,287 to (roughly, give or take) 495 – less than one and a half years’ worth of different breakfast combos.

Problem solved. But this is only the first level of complexity, just one portion of the necessary maths. To run a successful business, you need to consider that not all these ingredients cost the same to buy, so you would need to somehow give each combination a profit weighting, which would also be influenced by the popularity of each ingredient, the economies of scale in which it can be ordered and the likelihood of wastage. To get all of this down to a list of four of five different sets, with the odd personalized special thrown in, involves a complex web of invisible, delicate golden threads. When you dare to ask to substitute even mushrooms for beans, because you’re one of those people who doesn’t really like mushrooms because they’re a bit slimy, you might think you’re substituting one vegetable for another, a simple operation because both are on the same stove top and both are the same price on the extras menu. You fool! Don’t you realize you’re upsetting the balance of the universe itself?

And to think I used to assume it was just because the waitress didn’t want to complicate her order pad or the cook was lazy.

Of course, you’re now thinking that it would all be much easier if restaurants like Andrew’s simply listed all possible breakfast ingredients and assigned a price to each individually so you could build your own breakfast. Well, it’s funny you should say that. Because, aside from all the combinations on the boards above the counter, on another wall Andrew’s boldly innovates with its All Day Choice Breakfasts menu. Twelve separate ingredients are listed (if you want a fried slice with your All Day Choice Breakfast, you can forget it, but this is where the burger makes its entrance) and you can select any two of these for £2.60. You can then add more ingredients and the total price goes up. I try to fathom how this has been worked out, what the economics are, and quickly realize I need to plot it as a graph to make sense of it.

Chart One shows what seems to be a roughly linear and commonsensical progression: the more items you have, the more your breakfast costs. But look more closely and the relationship isn’t as linear as it seems. To make this clearer, I crunched the numbers to show the additional cost of each ingredient added.

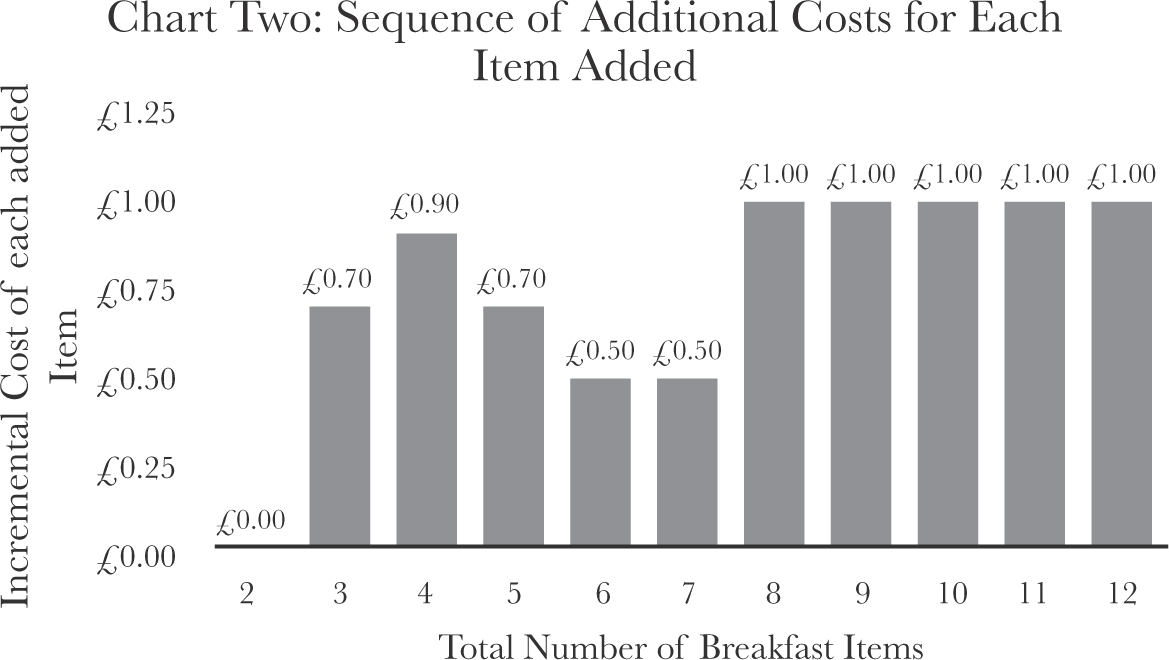

Chart Two shows that it costs 70 pence to add a third item, then 90 pence to add a fourth. As we’ve established, four-ingredient breakfasts are terrifying, so you’re then financially incentivized to add a fifth, sixth and seventh ingredient, before being punished for getting greedy.

We can therefore now use this data to work out the best breakfast deal when building your own by working out the average cost per item at each level.

As fans of Chart One will have realized already, Chart Three confirms that the two-item breakfast is a complete rip-off. But who orders a two-item breakfast anyway? If you do, you deserve what you get. The economics gradually improve, but not in a totally linear way, until the value peaks at a seven-item breakfast, which costs just 84 pence per ingredient, compared with £1.30 per ingredient for the two-item breakfast. The greediness tax of £1 for each additional item then kicks in, but such is the improvement in value leading up to seven, and because you’re progressively dividing the additional cost per ingredient between an ever-greater total number of ingredients to get the average, even when you get up to twelve the price per ingredient has only reached the same level it was at six.

I’m sure you’re now thinking, ‘Well, this is compelling stuff, Pete, but I’m dying to know – how does this build-your-own scenario compare with the value of the set breakfasts? As established, well-worn combinations, are they financially incentivized?’

I’m glad you asked. A direct comparison is difficult because each of Sets One to Four, Andrew’s and the Full English come with two slices of toast or bread and tea or coffee, which are not included in the build-your-own menu. However: the full English consists of seven items on the plate and it costs £6.50, compared to an All Day Breakfast Choice seven-item at £5.90. Two slices of toast bought separately is 90 pence. Tea is £1 and coffee is £1.50. So yes, as you’d guess, the full English eventually works out £1.30 cheaper than the same breakfast built separately.

After conducting this analysis, I decide to go for the full English breakfast. I was always going to anyway.

Like every breakfast, bacon and eggs are at its heart. The sausage in addition to the bacon makes it luxurious, while the mushrooms – which appeared on the working-class breakfast plate only in the late twentieth century, when dedicated farming made them more affordable – give the whole plate a healthier hue. I enjoy the crunch of a cheap, nasty hash brown, the American import that gives the plate a cosmopolitan air. And the baked beans give it its conversation points: we call them baked when in fact they are stewed and, while we now think of them as the most mundane workers’ café staple, when they were first imported from the United States they were a luxury item, available only from Fortnum & Mason until the end of the 1920s.

Andrew’s full English appeals because of what’s not on the plate as well as what is. I like the idea of tomatoes with breakfast, but they only ever seem to be half cooked unless you get a posh version with juicy, sweet, bursting, baked cherry tomatoes. I’m not over-fond of black pudding, and I’ve yet to find bubble and squeak in a café that’s anywhere near as good as what Liz makes at home.

And then there are chips.

The addition of chips to the roster of acceptable ingredients for a full English breakfast troubles me. It’s a southern thing. In the north, we love chips more than anything, but there’s something vulgar about adding them to the breakfast plate. It’s like having dessert before the main course, or pouring gravy on a cheese sandwich. Justine, one of my closest friends, doesn’t eat chips very often and isn’t even from the north, but she encapsulated my unease perfectly when we were discussing the issue and she said, ‘But if you have chips with breakfast, what are you going to have for the rest of the day?’

Exactly.

I order at the counter, find an empty table and sit down. Seconds later, a waitress places a mug of tea on the table in front of me. It’s served exactly as it should be, milk already in, teabag still in the bottom of the mug, leaning against the bowl of a teaspoon, like a happy drunk against a lamp post. The tea is the colour of He-Man’s skin, already so dark and tannic the spoon seems capable of standing upright, given a bit of encouragement. A minute later, my ‘2 Toast’ arrive, white bread gently browned and crisped, the crusts still soft, the margarine melted and fully absorbed, a light golden haze in the middle of the lightly tanned bread.

The main meal arrives just as I’m starting to wonder if I’ll need more toast. It’s presented on a white oval plate – the specialist equipment you only get in cafés like this. The surface area is undoubtedly greater than that of a standard dinner plate but the only way everything can be fitted on is by piling it up. Dominating the east wing of the plate, about a quarter of the total area, is a reservoir of baked beans. A single sausage, glistening brown, has been deployed as a makeshift dam to keep some room for other ingredients, but it’s only half as long as it needs to be and the beans seep around its edges. To the south they pour into a mountain of fried mushrooms, halved vertically through their stem and then sliced chunkily to form a pile of thick ‘J’ and ‘L’ shapes which here and there sport the tan of caramelization rather than simply the slickness of sautéing. Two crispy hash browns dominate the west side of the plate, half obscuring a fried egg whose yolk peeks out from under the potato, squished slightly by its weight, without quite breaking. The yolk is adroitly cooked, a compromise between two schools of thought on the perfect fried egg: the outer edges are cataract-misted by the fat, the centre still shining bright yellow, ready for piercing and dipping. There’s no room left for the bacon, so two rashers are laid like extra blankets atop the northernmost hash brown, putting further gentle pressure on the egg. The bacon, too, is perfectly judged – the edges crispy, the start of some browning on the flesh, but still succulent and juicy.

And it tastes exactly how I wanted it to taste. It’s good. It’s not outstanding. Erdogan Garip was not down at Smithfield Market this morning sourcing these ingredients directly from celebrated livestock farmers, and rightly so. I strongly suspect that the beans are Heinz and the hash browns were in a frozen packet until ten minutes ago. That’s exactly what we want from this meal. Churches don’t use Château Margaux and artisanal sourdough for their sacrament of communion, and neither does the English café. The mushrooms taste like mushrooms and the bacon is a bit salty and has some body to it. The baked beans are sweet and the hash browns are hot and soothing like baby food inside their crispy crunch. The sausage has the deep satisfaction that you get from a bit of filler along with the meat, the kind that, if you grew up eating them, means that you can only ever admire a free-range, rare-breed 95 per cent meat sausage rather than truly loving it.

What do you mean, ‘What about the egg?’

It’s a fried egg. Fried eggs are all the same. I wish I’d dared ask for poached. But that would have been too posh and would have spoiled everything.

Andrew’s full English breakfast is no better and no worse than I’d expect from an authentic café with a good reputation. It’s honest, reasonably priced and hasn’t been mucked about with. It’s not Newforge House, nor even Malmaison. So why do all these celebrities come here to eat? The workers come looking for calories to fuel them through the day, but the newsreaders? The old lady with her granddaughter at the next table? Nigella bloody Lawson? They’re here for something else. They’re looking for simplicity, satisfaction and a connection to something bigger, something real. As sales of bacon and sausages plummet in value every year thanks to misguided and misleading scare stories about cancer, and while ‘developers’ destroy our culture and replace it with monotone corporate brown, eating here is a political act.

Andrew’s will serve you breakfast at any time of day, and there’s something transgressive about that. It’s not as wrong as chips with breakfast, obviously, but it still feels naughty. There comes a time that must mark a cut-off point for breakfast and we must finally accept that the day is well and truly, irreversibly, under way. McDonald’s famously declares this moment to be ten thirty, but what do they know? For many establishments, this magical beat is at noon. Whenever it is, afterwards, the fixings for breakfast are still there, like they’ve always been, but it would be wrong to have them now. So when a café or pub announces that its breakfast is available all day, it’s an illicit thrill. Imagine eating a cooked breakfast in the evening!

Here in Andrew’s, the clock hands reach eleven and a change comes over the place. There’s no alarm, bong or announcement, because we don’t need it. The volume of conversation drops. Half the tables empty, all at once. The timing, like the composition of set meals and strict rules around substitutions, like apple crumble being available only on Thursdays, reveals that, when it comes to our favourite meals, we like to be bound by rules and conventions. We British are quite comfortable with a bit of light authoritarianism, with being told what we can and can’t do. No matter how long it’s available, you shouldn’t be needing breakfast after eleven. There’s work to be done. Whether you’re reading the news or digging the road, it’s time to get on with the day. Keep calm, and carry on.