THE ALLURE OF the digital dream in education has been persistent and pervasive in the face of serial disappointment. For frustrated politicians and administrators, the absence of actual evidence of effectiveness has proven no match for the burning desire to deliver a dramatic new solution to the seemingly intractable problems in education.1 For managers and shareholders, the bodies of those who came before have not dissuaded them from seeking the next magic elixir offered to cure the sector of its slow growth and propensity for missed earnings.2

In K–12, policy makers who still dare to dream must confront not only the lack of demonstrated results to date but also the substantial opportunity costs of diverting resources to pursue digital solutions. For instance, a recent influential analysis concluded that once the network, content, training, management, and needed devices are accounted for, the cost of using an iPad textbook is more than five times that of using a traditional print textbook.3 The prospect of being able to ultimately deliver a “personalized” electronic solution to every child’s problems is so compelling, however, that few pause to consider fully what this really means or whether it is either practical or desirable.

Even outside of education, the conceptual appeal of the disruptive paradigm has not been matched with results. Historian Jill Lepore has shown that the handpicked examples used in the bible of disruption—that is, Clayton M. Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma5—were actually more often than not the result of “incremental improvements” rather than transformative technologies.6 The more fundamental problem, from a financial perspective, is that the ability to digitally disrupt an established marketplace is unlikely to lead to a particularly good business. Whatever kink in the armor of the established order that allowed the introduction of a new competitor is very likely to attract many more and make the new order much less profitable than the old one was.

Two leaders who have nonetheless managed to demonstrate an ability to successfully disrupt an entrenched incumbent regime are Rupert Murdoch and Joel Klein. Murdoch has created multiple profitable and resilient franchises in established domains, often by fundamentally changing the rules of the game. Many others had tried and failed to become credible competitors to the BBC, the three U.S. broadcast networks, and CNN, but only Murdoch found ways to do so. In an entirely different realm, Joel Klein used his perch as chancellor of the New York City public schools to discard a wide range of stultifying institutional orthodoxies that previous heads had found immovable. Although controversial, it is hard to argue that Klein did not succeed in changing the landscape of the possible in public education—not just in New York but nationally as well.7

These kindred spirits found in each other the perfect partner through which to apply their unique abilities and track records to fundamentally disrupt the K–12 educational marketplace. They did this by simultaneously taking on the global multibillion-dollar leaders in educational hardware, software, and curriculum. But after five years and more than $1 billion spent, with no serious prospect of ever turning a profit, their venture, called Amplify, would be sold for scrap value. In the interim, Amplify played a role in the break-up of Murdoch’s overall media empire. It is worth taking a closer look at how this promising partnership came to be and how it then unraveled, having made no significant ripple in an increasingly crowded field of more focused early-stage educational ventures bent on leading their own education revolution.

With unprecedented frequency in recent years, public corporations have been splitting themselves up. Alternatively spurred by activist investors, a desire to shed underperforming assets, or simple frustration with a perceived “conglomerate discount” in the company’s stock price, tax-free spinoffs have been embraced by the public markets. On the mere announcement of a company’s intention to spin off a division, shares frequently rebound sharply. Indeed, shareholders are so appreciative of the separation that the remaining company frequently is valued higher without the offending holding than with it—even before taking into account the value that shareholders receive for their ownership of the spinoff company.

The market euphoria over the advantages of spinoffs has led to significantly less focus on the behind-the-scenes “sausage making” that goes into the corporate preparations preceding the separation. By the time the newly independent company actually starts trading, a series of critical questions must have been answered: Which assets should be included? Who from management and the board should go with the spin? How much of our debt should we burden the spun company with? What kind of business arrangements should continue between the two companies, and what are the “fair” terms of those arrangements?

These questions are all highly politically charged. Those who will go with the spinoff vehicle want to ensure that it is poised for success on its own. Their interest will be in getting as many attractive businesses as possible, starting out with a pristine balance sheet, and having access to any critical resources retained by the remaining company on an acceptable basis. The team staying behind, by contrast, often will be focused on something altogether different: how do I use the spinoff to get rid of all the problems that have historically constrained my operating flexibility and tempered my unconditional embrace by investors?

The complexities around all the details of a separation frequently require a year or more to execute. Financial, legal, and accounting advisors are hired, corporate project teams established, and code names given for “SpinCo” and “RemainCo.” Given the predictable political dynamics described, however, one informal name for the to-be-spun entity often emerges as an internal company favorite: “ShitCo.”

Viacom’s 2006 spin-off of CBS was typical in this regard. Viacom kept the sexy businesses, like the movie studio, and its faster-growing segments, like the cable channels. CBS, by contrast, got the slow-growth businesses like book publishing; a disproportionate amount of the company’s debt; and, for good measure, legacy liabilities, such as asbestos exposure litigation dating back to predecessor companies. Tensions between the companies from the treatment of CBS as “ShitCo” linger to this day. But CBS had the last laugh by outperforming Viacom in the ensuing decade and recently even executing a spinoff of its own of the company’s billboard assets. More often than not, however, “ShitCo” remains “ShitCo,” floundering as an orphan stock, sold, or broken up.

The decision by Murdoch to split up his media empire into two separate companies had particular resonance with public investors. Historically, Murdoch had made daring unconventional bets that, over the decades, had accrued to the benefit of all shareholders, even as, at times, they risked the company’s very survival: the launch of the Fox Broadcasting Network in 1986, the creation of BSkyB in 1990, and the establishment of the FX Network in 1994 and Fox News in 1996. By most key operating metrics, News Corp. appeared to be the best run major media company through most of this era. The net result was that, with the exception of the first five years of Michael Eisner’s tenure at Disney, News Corp. had consistently been the best performing media conglomerate for decades.

Write-offs had been piling up since 2001, totaling almost $25 billion,10 and the share price lagged both the market and its peers. Indeed, where once there had been a Murdoch “premium” in the stock, the growing perception of unreliability among investors had created a Murdoch “discount.” So when rumors first surfaced in 2012 that News Corp. would establish a “ShitCo” of its own to house Murdoch’s various “enthusiasms,” it surprised no one that the shares of the company jumped almost 10 percent.11

The Birth of ClownCo

The devil, as with all such plans, was in the details. As first reported, News Corp.’s “ShitCo” was characterized as encompassing Murdoch’s various publishing interests. These included not just the New York Post and a coupon-distribution business in the United States, newspapers in the UK and Australia, and HarperCollins, the global English-language book publisher, but also the entirety of Dow Jones (owner of the Wall Street Journal), which Murdoch had purchased for $5.6 billion in 2007. The fact that the company had been forced to write down fully half the value of the Dow Jones acquisition only a year after closing the transaction may have represented a turning point in investor attitudes toward Murdoch.12

First, unlike most spinoffs, Murdoch would remain executive chair of both companies. This was also true of Sumner Redstone’s relationship to Viacom and CBS, though at the time, he had been clearly more focused on the long-term value creation from a high-growth Viacom. By contrast, Murdoch actually had a stronger personal emotional attachment to “ShitCo” than to “RemainCo.” Although he was nominally CEO only of “RemainCo,” the day-to-day management reality reflected his primary preoccupation with “ShitCo.” Executives back at what would soon be called 21st Century Fox had never had any interest in the publishing assets and viewed the Dow Jones acquisition as a costly distraction. That said, they knew that any attempt to pull cash out before the spin and encumber “ShitCo” (which would retain the News Corp. name) with debt would be angrily dismissed by Murdoch. So rather than the typical situation, there was a genuine commitment to ensuring that the company had all the resources it needed to survive independently, indefinitely. Given Murdoch’s perspective, management at Fox was thrilled to see these businesses jettisoned at all.

Second, absolute size notwithstanding, the operating trajectory of the publishing assets was troubling. In 2012, the profit of the news and information business fell almost 20 percent and was anticipated to continue to experience double-digit percentage declines for years to come. Although the low-margin Harper Collins book business had managed to keep profits relatively stable, in 2012 it represented less than 10 percent of the profits of the other publishing businesses.

Third, and maybe most important, in 2010 Murdoch had decided to go into the education sector through the acquisition of a small business called Wireless Generation. Since then, the company had broadened its educational sector ambitions into areas far beyond those in which Wireless had originally operated. By 2012, Murdoch’s collective educational endeavors were losing close to $200 million annually, with no near-term prospect of profitability. In the context of a company the size of the combined News Corp., losses like this or that of the New York Post could be managed without bringing undue attention to them. In the context of a far smaller News Corp., however, with fast-shrinking profits in its core businesses, these numbers mattered.

It was an unusually hefty divorce settlement but, based on the market reaction, a very fair price for independence. The value came not just from eliminating the distraction from managing this mix of mostly declining or money-losing activities of no apparent strategic value. It also came equally from the implicit understanding that News Corp. would be the vehicle from any future shareholder-unfriendly Murdoch initiatives.

For the remaining management at Fox, almost any price was viewed as a bargain. They had long been pressing for a separation, which Murdoch had resisted even as the pace of his shareholder-unfriendly actions quickened. It was only when the News of the World hacking scandal erupted in London that Murdoch allowed the spin-off to move forward. To be fair, the code name used at the company during preparations for jettisoning Murdoch’s beloved assets was not “ShitCo.” In fact, the name of this book is partially an homage to the only slightly less pejorative name used internally: ClownCo.

If the Dow Jones write-down represented a turning point in investor attitudes toward Murdoch, the decision to take on the business and political education establishment on the shareholders’ dime was something else altogether. This decision reflected a willingness to take on challenges completely unrelated to the core business that had no obvious limitation on their required investment. If not subject to some constraint, this venture had the potential to take the “Murdoch discount” to an entirely new level. It was this, more than any other single financial consideration, that made the separation of ClownCo so essential to the shareholders.

The entry of Murdoch into the education business, however, had none of these mitigating considerations. Part of operating management’s frustration was that the initiative began just as they were trying to focus the company by divesting or closing a long line of earlier distracting, Murdoch-sponsored projects. MySpace was sold in 2011, The Daily was shuttered in 2012, and IGN Networks was sold in 2013, all for a combined loss of over $1 billion. The company had little expertise in the educational sector and no significant assets to which it was strategically connected. Although Murdoch had previously owned educational publishing assets, they were ultimately divested after he, along with a number of his media conglomerate peers who had made the same strategic mistake realized their tenuous connection to the rest of his media empire.

That had been almost twenty years earlier.14 Since then, Murdoch had gotten a taste of just how much money could be quickly lost trying to “transform” education when his friend Michael Milken asked him to invest in his Knowledge Universe venture. It was never completely clear to Murdoch precisely how the money had disappeared so fast, but he certainly knew that education had not been transformed and that he had gotten a small fraction of his investment back. Although buried in the footnotes, Murdoch wrote off $92 million of his $100 million investment in a subsidiary of Milken’s Knowledge Universe.

15 The losses envisioned for this new educational initiative dwarfed anything he had given Milken and even a decade of losses at the

New York Post. Education, it could be said, is what gave “ShitCo” its stink.

Murdoch’s announcement at the time of the Wireless Generation acquisition did nothing to temper concerns about the scale of future investment being contemplated. “We see a $500 billion sector in the U.S. alone that is waiting desperately to be transformed,” Murdoch gushed. In his view, the business he was buying was “at the forefront” of technology that was “poised to revolutionize public education.”16

Regardless of whether Klein played a direct role in Murdoch’s acquisition of Wireless Generation, it is incontrovertible that Klein’s tenure as chancellor fundamentally shaped that company’s development. That history is central to understanding both the otherwise inexplicable acquisition and the apparent belief that this modest educational business could serve as a platform from which to fundamentally transform K–12 education as we know it.

Welcome to the Wireless Generation

The large educational publishers he approached, however, expressed little interest in partnering with him to help achieve this vision. As it turned out, the main practical application of the wireless technology was for DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills), a formative reading assessment product serving the K–3 market. Particularly in the early grades, allowing a teacher to observe individual student performance and enter it into a handheld device was an extremely efficient way to administer assessments and collect data. The DIBELS assessment was owned by the original developers, not Wireless, and its validity was a subject of heated controversy among academics and school administrators.21 But, wisely or not, it had been adopted broadly, and Wireless Generation’s application—called mCLASS—became very popular, driving the company’s growth.

The entire K–3 formative assessment market, however, was not very large. Although DIBELS-related activities still represented a majority of Wireless Generation’s revenue, by the time of the Murdoch acquisition, that market had already been saturated, and overall revenue in 2010 was actually down from the prior year.

An opportunity for Wireless to expand beyond its niche came in the form of Chancellor Klein’s belief in the potential for technology to accelerate his efforts to transform New York City’s public schools. Although much of the focus of his tenure after being appointed in 2002 had been on organizational and school design issues, Klein had early on signaled that technology would play a central role in his overall Children First reform strategies.22 Technology, Klein asserted, “is one of the most underused assets in terms of the future of educating our children.”23

Although the initiative reflected laudable aspirations, there were no successful systems currently in place that did everything sought by New York. In addition, a number of similar but less ambitious efforts had ended badly—and expensively—with angry recriminations all around.24 In North Carolina, the first year rollout of an accountability system had taken ten years. Chicago had fired its first vendor, only to have to shut down the system installed by a second vendor due to massive data errors and lost student information. Large districts in Florida and Texas both faced system meltdowns, resulting in lost data, millions in cost overruns, ad ultimately more rather than less work for existing staff. Thus, any procurement process of this magnitude would need to be carefully managed. In this case, given the lack of favorable precedents, additional care would be required to establish sensible and achievable technological and operational requirements.

Klein hired a chief accountability officer to spearhead technology initiatives. This new chief accountability officer would report directly to the chancellor and be responsible for developing standards, selecting contractors, and managing implementation. Selected for this role, however, was not an expert in technology, education, or procurement, but James Liebman, a professor at Columbia Law School with an impressive record as a public interest lawyer and a leading expert on the death penalty.25 The incumbent chief information officer (CIO) of the department, Irwin Kroot, who had been a senior consultant at IBM and Price Waterhouse Coopers, would quickly depart within months. The next CIO, Ted Brodheim, would not be appointed until the following year, after the contract had already been awarded.26

Not very much was publicly disclosed about the procurement process Liebman led. And the thirteen-member oversight board that had been put in place when the mayor took control of the public schools did not review the process.27 A number of the nineteen competitors for the massive contract thought its scope was overly broad and that the proposed timelines for project implementation were simply impractical. Some suspected that onerous technical specifications had been included at the behest of IBM, which was ultimately awarded the contract.28

Another competitor for the New York City Department of Education contract was a consortium that included a business called SchoolNet. Although a relatively small business, SchoolNet had focused exclusively on developing scalable, data-driven IIS since it was founded in 1998. By 2006, it was on the fifth version of its core software. The company was by far the market leader in large school districts and had been operating successfully in neighboring Philadelphia since 2002. Indeed, it had also been operating its IIS successfully in Chicago, even as IBM was in the process of losing its SIS contract there.

SchoolNet did not have the capabilities to perform all the functions required by the RFP and had partnered with Deloitte. Jonathan Harber, the CEO of SchoolNet, had met with Liebman to argue that the proposed timelines—three months to have a pilot up and running and an initial full release four months later—were not achievable. Only SchoolNet, he argued, had an existing IIS product that could be up and running that quickly, allowing the additional functionality to be built on top later. Liebman was not convinced and remained committed to launching a system that would represent the first of its kind.

The other potential piece of good news for Wireless Generation was the establishment in 2009 of the $4.35 billion Race to the Top Fund for which states would compete.33 Race to the Top (RTT) was a boon to IIS providers because each winner was required to set aside part of the funds for a statewide IIS. Although Wireless Generation’s experience with ARIS could, make it a contender for these funds, the reality was that being asked to “fix” a troubled project that was already “well under way”34 was a far cry from having a commercializable product to market—but it definitely represented a new opportunity.

The other key asset that Wireless Generation had was its CEO, Larry Berger. At a time when education funds were frequently directed or influenced by philanthropies and think tanks, having a leader who played well to that constituency was crucial. Despite the relatively narrow domain in which his company operated, Berger had become a popular evangelist for both the potential of technology to transform education in general and—reflecting his own bitter experience trying to get them to adopt Wireless Generation’s technology—the “challenges to breaking the monopolies held by the educational publishing companies.”35 In fact, it was through a widely delivered PowerPoint presentation on these and other “barriers to innovation in the education sector” that Berger established himself in the community. He served on boards of influential educational philanthropies and thought leaders like the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, and even the nonprofit corporation that owned the leading industry trade publication, Education Week.

This work proved particularly valuable in securing a contract to create the algorithm for something called the School of One. This program was the brainchild of New York City Department of Education employee Joel Rose, who conceived of developing a daily individual learning plan for students based on their specific needs—identified after collecting data and applying predictive algorithms. So compelling was this concept that it ultimately attracted funding from thirty different private entities—notably, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation, a sister organization to the one on whose board Berger at. Again, there was no RFP for the project.

So, after a decade of struggle, as Wireless Generation started 2010, it had a great deal to feel good about. Although its core business had slowed, Berger had cultivated a couple of promising new avenues through which to reaccelerate its growth. The company faced one existential problem, however, that it urgently needed to address. It was running out of money.

Wireless and Cashless

Wireless Generation had raised just under $20 million over five funding rounds between 2001 and 2005. The last of these, at more than $6 million, had been the largest; it valued the business at $58 million, or just over three times revenues at the time. By the beginning of 2010, the company still had close to $8 million in the bank, but it had eaten through more than $6 million just in the previous year. These amounts understate the peak cash needs of the business. In K–12 education, cash flows fluctuate dramatically over the year. Even the largest and most profitable businesses have quarters—when product is being developed and customers are being solicited in anticipation of the fall enrollment—that are a significant drain on cash.

What’s more, Wireless Generation would need to spend more than $10 million in the coming year on software development and other capital expenses to support its hoped-for growth. This amount would ramp up in future years as the new initiatives developed. To deal with these cash needs, the company arranged to borrow $5 million during the year from the Kellogg Foundation. It was clear, however, that a more permanent liquidity solution needed to be found.

At just that moment in early 2010, as Wireless was pondering its options, Berger was approached by Pearson about acquiring the company. Based in London, Pearson is the largest global education publisher. At that time, neither of the two other major K–12 publishers were in a position to pay an outsized price for the company. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt had just undergone one of its now regular restructurings and was in no position to make an acquisition. McGraw-Hill’s educational unit had been a drag on its overall performance, such that shareholders would likely be horrified by the announcement of a significant acquisition of a money-losing, slow-growing business. (Indeed, the following year, an activist investor would push McGraw to spin off its educational business altogether.)

The call from News Corp. was unexpected and came from an unlikely source. Rupert Murdoch, they learned, had apparently hired Kristen Kane, the former COO of the New York Department of Education under Joel Klein, to “educate” him about the sector. The call was actually about another company—a digital education company called Time To Know, funded entirely by successful Israeli entrepreneur Shmuel Meitar.38 But when Berger told Kane that Wireless was having sale discussions, she immediately expressed interest. Given the obvious lack of strategic fit, Wireless was skeptical about News Corp.’s commitment to transact at a value that would be of interest to them, but Kane assured them that Murdoch’s interest in the sector was genuine. The good news was that this was true. The bad news was that absolutely no one else of importance at News Corp. had any interest in the sector and, indeed, they would all try to kill the deal at every opportunity.

True to her word, Kane called back quickly, and within days Berger found himself in a four-hour meeting with Murdoch himself. Murdoch did not blanch at the valuations that Wireless had been discussing with Pearson. To ensure that it wouldn’t leave any money on the table, Wireless had reached out to investment bankers to manage the process of selling the company or, if that failed, raising a sixth round of funding. Goldman Sachs had been hired in the summer of 2010 and was as surprised as anyone that News Corp. had expressed interest. The bankers were thrilled that they had been handed a horse race that was starting at the incredible price of at least $300 million.

Goldman knew both Pearson and News Corp. as well as anyone. The financial company had just managed the $3.4 billion sale of Pearson’s financial information business, and a former Goldman partner sat on the News Corp. board. Pearson, which owned the Financial Times, and News Corp., had a long history of animosity, arising not only from their competition in the newspaper market and ancient disputes stemming from their once-shared ownership of BSkyB but also from deep cultural differences.

Goldman adroitly used the deep-seated competitiveness between Pearson and News Corp. to ensure that the ultimate price would reflect most, if not all, of the synergy value from the most strategic buyer. Goldman shared a term sheet reflecting Wireless’s wish list of financial and commercial terms in a deal and asked both parties to put their best foot forward in marking up the document. The lack of any internal constituency for the acquisition at News Corp. beyond Murdoch led the company to cool somewhat on the transaction. In the early fall, however, bankers were still able to use the perception of genuine competition to force Pearson to move its price to an astounding $360 million.

Having now agreed on the price and key contract terms, Pearson knew that no other party was still involved in the process. This led to a lack of urgency and increasing intransigence on remaining open issues on its part and a building frustration on Wireless Generation’s part. By November, the contract was still not quite signed.

Then, on November 9, Joel Klein announced he was leaving the schools job for the Murdoch empire at year-end. Shortly thereafter, News Corp., which had previously terminated conversations with Wireless Generation, suddenly reached back out to Goldman to see whether the contract with Pearson had actually been executed. In fact, at this point, all of the key outstanding issues had been resolved with Pearson, and an agreement on a final signing the following Monday had been reached. That said, Berger not only was annoyed with the pace of final negotiations but also was ambivalent about being owned by one of the educational publishers he had long railed against. He let it be known that if News Corp. topped Pearson and agreed more or less to the original “wish list” term sheet, Wireless Generation would be theirs.

Berger and his team spent the weekend finalizing in days with News Corp. what had taken months with Pearson. So worried were they that Pearson would find out what was afoot that Wireless didn’t even tell their own banker, who they feared could not resist engaging with the educational publisher. When frantic Pearson executives were unable to contact Wireless, the Goldman bankers admitted to having no idea where their client was or what they were doing. As announced publicly, the total value placed on Wireless Generation was $400 million. In fact, the actual price ultimately paid was substantially more.

As little sense as the initial acquisition made, it was genius compared to the strategy undertaken once the asset was owned by News Corp. The subsequent losses incurred would dwarf the price paid.

Enter the Chancellor

Joel Klein is a very impressive person. After clerking for the Supreme Court and a few years at a well-regarded litigation boutique, he founded a firm with two colleagues that was widely viewed as developing the premier Supreme Court and federal appellate advocacy practice in Washington, D.C.40 What followed was a distinguished career in the Clinton White House and Justice Department, culminating in a stint as antitrust chief, where he successfully prosecuted Microsoft.

Brill described Klein’s eighteen-month tenure at the German media conglomerate Bertelsmann after leaving the Justice Department as “a daring jump out of law and government” into a corporate operating job.43 According to Brill, Klein “was responsible for business ranging from Random House books to Sony BMG Music to Gruner + Jahr Magazines.” This statement is not accurate. Each of the businesses mentioned by Brill (only one of which was wholly owned by Bertelsmann) had its own management teams, none of whom thought that Klein had much of anything to do with them.

Although Klein had the title of chairman and CEO of Bertelsmann Inc., this was merely a holding company for the U.S. assets of a number of the company’s divisions. Indeed, “Bertelsmann’s most prominent feature is its decentralization,” with generations of leaders leaving all key strategic and operating decisions to the divisions.44 Bertelsmann CEO Thomas Middelhoff brought in Klein for a staff role to “advise on legal and strategic governmental issues, working closely with the heads of Bertelsmann’s U.S.-based operations.”45 Klein had limited staff of his own and never had any authority over any of the company’s business units. The Wall Street Journal referred to Klein as “a roving executive-without-portfolio.”46

Klein’s weakness in operational management was also viewed as an Achilles heel during his eight years at the New York City Department of Education. The New York Times speculated that Klein had been pushed out due, in part, to his resistance to accepting a new chief operating officer imposed by the mayor’s office.47 None of this dissuaded Murdoch from agreeing to employ Klein when he called over a weekend to say that his tenure as chancellor would be ending imminently.48 The sudden decision to hire Klein was not as surprising to News Corp. executives as was the agreement to put him on the News Corp. board of directors. A hastily arranged board call effectively ratifying this promise could solve the short-term awkwardness caused by Murdoch’s decision. And yet, the longer-term awkwardness created by having the architect of what would become a costly mistake serve as part of the supposed oversight body could not be as easily resolved.

To be fair, in addition to being the leading advocate for the school reform initiatives in which Murdoch deeply believed, Klein had other important skills that could prove useful to Murdoch. Klein had not only shown himself to be a singularly effective advocate both in and outside a courtroom, but he was also a highly respected Democrat at a time when Murdoch had recently lost his most important conduits to the other side of the aisle. Both Peter Chernin, the highly respected president and COO of News Corp. for over a dozen years, and Gary Ginsberg, an executive vice president “who often served as a liaison between the conservative Mr. Murdoch and the Democratic Party,” had left the previous year.50 More broadly, Klein had a remarkable ability to not just network but also connect individuals of diverse interests and backgrounds with unexpected and sometimes truly spectacular results. For instance, Klein’s introduction of real estate and media mogul Mort Zuckerman to neuroscientist Eric Kandel resulted in the establishment of the $200 million Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute at Columbia University.

But that still left the question of what precisely Klein would do at News Corp. It was initially suggested that he would “advise…on opportunities to invest in digital initiatives in the educational market.”51 Although the company said Klein would advise Murdoch on a “wide range of initiatives,” sources emphasized the focus would be specifically on “seed investments” in “entrepreneurial ventures.”52 When the Wireless Generation deal was announced soon thereafter, Klein’s role became even more unclear. Wireless Generation was not a seed investment and had a complete management team under Larry Berger, all of whom would be joining News Corp. Indeed, the Wireless senior management had been explicitly assured that they would be operating independently and not reporting to Klein.

The Education of Rupert Murdoch

The first round winners of the RTT competition among states had been announced in 2010, and late in 2011, statewide IIS contracts were being awarded with those funds. The results were foreshadowed, as some of the states that had been unsuccessful RTT finalists, such as Kentucky, had already begun to contract for these systems with their own money. The winner of the Kentucky contract, and ultimately of a majority of the competitive RTT contracts, was SchoolNet, the company New York City had earlier rejected in favor of IBM and Wireless Generation for the implementation of ARIS. By 2011, SchoolNet’s system had already been adopted by a third of the large urban school districts. Pearson purchased SchoolNet in April 2011 for about half of what News Corp. paid for Wireless Generation.54

Although Wireless Generation did take over the original ARIS contract from IBM in its entirety in 2012, New York City announced soon thereafter that the ARIS system would be phased out entirely. The problem, it seemed, was that very few people—principals, teachers, or parents—actually bothered to use the system, which had been subject to continual complaints once it was finally fully installed.57

In the aftermath of the collapse of News Corp.’s educational foray, some would point to the hacking scandal—and the loss of the New York contract, in particular—as an unforeseeable external event that doomed what would have been an otherwise successful venture. But such claims do not hold up to scrutiny. First, New York didn’t bar the company from doing business with the state or city. Indeed, it would continue to work with Wireless Generation as part of a $44 million foundation grant the company had received in 2011 to build the Shared Learning Collaborative, as well as in connection with the city’s School of One contract. Second, Wireless Generation ultimately did not win any of the competitive bids for state IIS contracts, some of which were awarded before the scandal broke. Finally, the legacy Wireless Generation business represented a tiny fraction of the overwhelming losses that would eventually force the termination of the venture.

A related argument is that Murdoch’s decision to tap Klein’s legal and regulatory expertise to help deal with the hacking scandal for the company was what doomed the educational initiative. But the truth is that although he provided Murdoch with counsel on the topic, Klein never had primary responsibility for managing it and always spent the majority of his time on the education division. Furthermore, Klein had never actually run the business on a day-to-day basis. In addition to the operating teams, Klein had filled the corporate staff with senior executives, including Kristen Kane, who joined as COO of the division, along with a raft of “some of the biggest names in education.”58 Klein was responsible for the overall strategy, and there is little evidence that his temporary corporate distractions either changed these or slowed their implementation.

Wireless Generation’s association with the School of One initiative that some saw as a potentially revolutionary initiative proved similarly disappointing. Although School of One continues, it has failed to gain much traction in the half-dozen years since it launched. In 2011, Joel Rose established a nonprofit called New Classrooms Innovation Partners to further scale his personalized instructional initiative, now branded as Teach to One. By 2015, the model had attracted only fifteen schools in the entire country. Although some studies showed improvements in student performance from the program, others yielded more mixed results. Potentially more troubling was that even those who believed in the positive impact of Teach to One were not convinced it was worth the cost and disruption of implementation.60 From a financial perspective, the challenges were heightened by the fact that the program’s biggest customer—New York City public schools, representing six of the fifteen active sites—did not have to pay a license for the software because it had been developed when Rose was an employee of the system.

The net result was that after the first full year of ownership, Wireless Generation was far behind the projections that management had provided during the sale process. In addition, the effective purchase price had risen dramatically. Not included in the original $400 million were a variety of additional payments (on top of the $360 million and the 10 percent retained equity stake) related to certain specific performance targets. With Klein brought in as the leader of the overall effort, he wanted Wireless management focused on his various other new initiatives. Although Berger and the team agreed to redirect their energies, the quid pro quo was for News Corp. to simply pay out these substantial bonuses, regardless of the achievement of the targets. Whereas at the time of the purchase, Wireless Generation looked like it might be on the brink of breaking even, in 2011 the business had hemorrhaged cash. Results for 2012 looked even more dire.

A month after that announcement came the first hint regarding the extent of the expanding ambitions of the division. The company unveiled a new brand—Amplify—which would be broadly “dedicated to reimagining K–12 [e]ducation.”61 Although the Wireless Generation brand appeared late in the press release, its legacy activities were consigned to one of three divisions—now called Amplify Insight. The two other divisions were Amplify Learning, aiming to “reinvent teaching and learning” through new digital reading, math, and science curricula, and Amplify Access, which promised to introduce a new tablet-based platform with AT&T that bundled content and analytics for schools. No financial details were provided, and it did not appear that the two newer divisions had any sales or even products. It was clear, however, that Amplify had not been idle. Links in the release provided “early glimpses” of the “game-changing” products being developed. Amplify’s “next phase,” according to Klein, would be “ushering in a new age of teaching and learning.”

62

Any specifics had to wait until the education division and Klein’s strategic vision had their coming-out party, of sorts, at the UBS Global Media and Communications Conference in December 2012. This long-established annual event attracted investors from around the world and featured presentations from almost 100 companies in the sector.63 There Klein and chief product officer Laurence Holt took the group through almost sixty slides outlining their full ambitions for Amplify. It was only then that investors learned how much money was being lost and where it was going.

Amplify Conquers the World

When he turned to the details, Klein was brief but breathtaking. Both the scope of the long-term vision and the extent of the immediate-term losses were unexpectedly massive. Although the legacy Amplify Insight business had grown to $100 million in revenues, far behind the original plan, losses were now projected to approach $25 million—even before the new $10 million in annual costs accumulated at Amplify corporate. But the presentation made clear that, though they still contributed no revenues, the real focus of Amplify would be the start-up Access and Learning segments.

Amplify Learning also rated two dedicated substantive slides. From the voice-over, it was clear that they intended to build “brand new curriculum from the ground up” in English language, math, science, and even arts. Thus, in addition to competing with the leading hardware vendors, Amplify wanted to take on Pearson, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and McGraw-Hill Education, along with all of the focused start-ups targeting various aspects of the K–12 curriculum. The major publishers might spend $50 million or more on the competitive adoption process for a single subject in a major state and had invested hundreds of millions in digital curriculum. Klein, however, suggested that the Common Core standards would massively simplify this adoption process and allow for the development of a single national curriculum that was “digitized,” “gamified,” and “personalized,” with “very sophisticated analytics.”

The problem with this view is that all of the existing curriculum publishers would also align their materials to Common Core standards. More important, states adopting these standards could still decide which provider to adopt and impose additional state-specific requirements as part of their selection process. It is not surprising that the track record of educational companies that try to break into the national curriculum market is poor, given the structural advantages of the scale incumbents. The record of those that conceived of curriculum as a way to enhance the attractiveness of their entrance into the distribution business is particularly abysmal.

A good example of the challenges associated with developing digital curriculum is K12 Inc., the leading provider of online public schools. In 1999, K12 wisely targeted a growing population of families who wanted to homeschool their children. Increasingly, state and public funds were being made available for these students to be served, usually through distance-learning charter schools. K12 provided the technology solution for these charters.

The trouble was that the cost of delivering the curriculum was so overwhelming that the business failed to deliver any cash flow. A competing business, Connections Academy, started years later but decided to focus exclusively on perfecting its technology solution and simply adapting the best of existing curricular solutions to its digital environment. Even at a fraction of the size of K12, Connections was far more profitable—which should not have been the case in a scale business. It also attracted fewer operational problems and less regulatory scrutiny.66 In addition, there was no evidence that the new digital curriculum performed any better. Pearson ultimately purchased Connections Academy, and almost ten years later, K12 still trades below its original IPO price.

As disturbing as the ballooning of Amplify Insight’s losses were, these were far smaller than those being generated by each of the two newer divisions. Amplify Access was slated to lose more than $61 million in the first year, and Amplify Learning would lose $85 million. The total projected operating losses of $180 million for the year were included on a slide headed “Amplify Disciplined Investment.”

If the general assurance that the investments were to be disciplined was not comforting to investors, the slide dedicated to the overarching investment thesis would provide little additional solace. In addition to not providing much of a thesis, it suggested that whatever software they had developed to improve English-language writing skills still had kinks to work out. “Amplify,” the slide declared in large enough font to fill the page, “is a balanced investment opportunity in the disruptive innovation in education.”

Typical of traditional software businesses, the current $100 million in revenues came overwhelmingly from enterprise software development and “professional services” (mostly in the form of consulting to customers). One of Amplify’s revenue mix targets was that it expected fully 75 percent of its expanded business to be generated by subscriptions. It is true that the emergence of so-called software-as-a-service (SaaS) business models has transformed how many software businesses get paid. Whereas enterprise software businesses obtain huge upfront implementation fees followed by relatively modest annual maintenance fees under a fixed-term contract (supplemented by hefty ongoing consulting services), SaaS businesses have relatively modest implementation fees followed by consistent open-ended subscriptions (which require more modest ongoing consulting). The result has been that software businesses that once required new sales every year to make their numbers could now rely much more on their ongoing subscription backlog. In the educational realm, however, this improved earnings visibility confronts a largely immovable object: local politics.

Companies serving local public schools are overwhelmingly paid pursuant to specific grants from state or local political authorities. These entities are not only subject to dramatic and unexpected turnover of personnel, but they also often have statutory limits on the duration of the financial commitments they can make. Many times, appropriations for a particular purpose are subject to a “use it or lose it” restriction. Nothing about the economics of SaaS business models changed the reality of the public appropriations process. Even if, in the abstract, a subscription business model is more attractive, those operating in the public school environment are often wiser to take whatever funds are made available as soon as possible.

Amplify’s other performance target—again, provided with no time line—related to the intended mix of revenues among divisions. At the time of the presentation, 100 percent of the revenues were coming from the Insight division. Eventually, as Klein told the assembled investors, this would decline to 40 percent, with the Access division contributing a similar percentage and the Learning division responsible for the remaining 20 percent. The trouble was, to justify the level of investment currently being consumed by Amplify, these targets either assumed a rate of growth that was inconceivable, a level of profitability that was unprecedented, or both.

At the end of the presentation, only a few minutes were available for questions. The first of the four questions asked was obvious from even quick math that a research analyst could do in her head: if the Learning business was only going to be 20 percent of revenues, why was Amplify investing almost as much in it as in the other two divisions combined? “Your slides were whizzing through so fast, I may have misunderstood,” a research analyst offered apologetically. “What’s the reason for that kind of mismatch?”

Klein responded by explaining that curriculum required significant upfront costs and that he would “expect [that] the revenue piece will accelerate in the further years out.” This response was not satisfactory for two reasons. First, as every curriculum developer knows, the need for significant ongoing investment is constant, reflecting the need for updates, changing state and local requirements, and any new funding opportunity—“upfront” costs aside. Second, the revenue mix target Klein provided for some point in the indefinite future presumably already should have reflected his hoped-for accelerated growth.

Given the magnitude of the cash flow drain, the new News Corp. would do everything it could to direct attention away from Amplify and leave the division’s precise ongoing losses ambiguous. In reporting its financials, News Corp. hoped to emphasize its four other operating segments—News and Information, Cable Network Programming, Digital Real Estate, and Book Publishing—along with its valuable 50 percent stake in the Australian pay-TV company, Foxtel. Amplify would be subsumed under “Other,” which included various general corporate expenses, along with the results of some small, noncore Australian businesses.

The strategy of diverting the focus away from Amplify initially appeared successful. The first Wall Street research reports on the independent company, issued in late 2013, often barely mentioned the educational division. In valuing the business based on the sum of its parts, some analysts gave News Corp. full credit for the $360 million in cash it had paid for Wireless Generation and added this to the values ascribed to the other operating divisions.68 Even those who simply valued the education division at zero were implicitly giving the company the benefit of the doubt by making no adjustment for what were anticipated to be hundreds of millions of dollars in losses over an unspecified number of years.69

Within a few months, however, some were publicly becoming more skeptical about Amplify. By September, Morgan Stanley had published research under the headline, What if Amplify Was Closed? “Amplify operates in a very competitive industry with entrenched interests on all sides that may be averse to change,” the analyst argued with significant understatement. Faced with the prospect of at least three more years of losses at similar levels, he drew the inescapable conclusion that “[a] path to an attractive return on investment for this business is unclear.”70

In fact, for the fiscal year ending June 2014, revenues for Amplify actually declined and losses increased, as did both operating and central sales, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses. This finding had implications for News Corp.’s regulators and auditors. Regulators wanted to ensure that investors had all they needed to make informed decisions and pushed the company to disclose Amplify’s results separately, rather than subsuming them within the “Other” segment. Auditors would need to be convinced that the value of News Corp.’s Amplify investment did not need to be written down. In the last quarter of the fiscal year, the company agreed to report Amplify as a separate segment. News Corp. somehow succeeded, however, in convincing its accountants, Ernst & Young, that no impairment charge needed to be taken—yet.

The potential value of the One Amplify initiative was not just in reducing the duplicative overhead and functions associated with each of the completely independent operations under Amplify—an organization that had ballooned to 1,200 employees. Those separate organizations often used different development tools and project architectures, making collaboration difficult. There were also complaints by former employees that “it was sometimes difficult to know who was in charge.”73 A scathing profile in BloombergBusiness described the uncoordinated sales processes pursued by the various divisions, with one client complaining, “The left hand doesn’t necessarily talk to the right hand.”74

In the end, the structural flaw in Amplify was not whether it had an integrated management structure or a decentralized one. It was that the organization was trying to do far too many things at once in the name of transformation. The K–12 educational market is characterized by large integrated players, on the one hand, and focused, product-oriented start-ups, on the other. In between are a variety of established niche players who focus on either a single product or service or a collection of tightly related ones. Amplify sought to be a combination of the two incongruous ends of the spectrum: a large integrated collection of mostly start-up initiatives. Given the inherent difficulty in simultaneously starting up and integrating, Amplify’s ambitions, on their face, presented a highly dubious proposition.

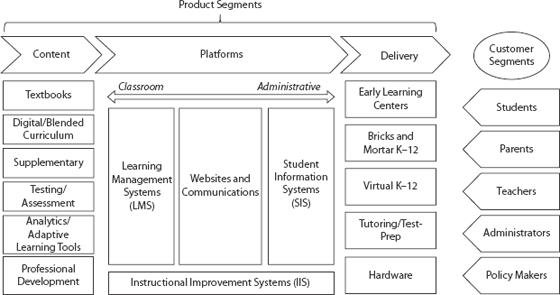

The simplified industry map in Figure 2.1 provides a flavor of the insurmountable fundamental challenges that Klein’s strategy presented. News Corp. would have been far better off if “One Amplify” had signaled a decision to focus on the single business line in which it had gained the most traction rather than a strategy of integrating a series of diverse subscale initiatives.

Figure 2.1 K–12 industry map

The great irony is that the only major segment of the K–12 market eschewed by Amplify was the one that was growing the fastest and in which scale seemed to matter the most—that is, learning management systems (LMS). This is not surprising given Klein’s demonstrably false view that “technology in itself has no inherent value in education.”76 According to Klein, “a cool tech platform without the content” would be “useless.”

One Amplify felt less like a new organizational strategy than a triage effort to address the building pressure from investors. CEO Thomson publicly promised in June 2015 that investments in the division would be “significantly lower” going forward.77 Soon thereafter, the company stopped actively marketing tablets. The CEO of Amplify Access had left the company in February and was not replaced. As the fiscal year came to an end, it was also clear that there would be no way to avoid writing down almost the entire value of the Wireless Generation acquisition. The company hastily began discussions with billionaire Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Steve Jobs, who had a long-term interest in the segment and serves as President of Emerson Collective.78 News Corp. hoped that when the financial results (and corresponding write-off) were announced in August, a clean exit could be simultaneously announced.

The history of Amplify highlights the huge gulf between admirable aspiration and effective execution in education. This has been replayed over and over again in the sector, with no end in sight. In an internal memo on the decision to sell Amplify, Klein acknowledged the failure of many of the far-flung products to gain market traction. In that memo, Klein diagnosed the problem with respect to all of their businesses, tablets included, was that they were too good: “In my view, Amplify’s work has been so innovative and transformative that we’ve been ahead of the market.”79

Klein has since become more forthcoming regarding Amplify’s failures in strategy and execution. For instance, with respect to the Amplify Learning products, he concedes it was a mistake to “serve people a full meal when what they wanted was a few appetizers.” That said, he continues to believe strongly in the product and in the animating proposition that “high quality curriculum coupled with an effective delivery system” is the key to driving improved student outcomes. And while Klein insists he wanted to succeed financially, that was not the primary driving force: “We were trying to change K–12.”80

Jobs and Berger moved quickly after the sale to reorganize and refocus the enterprise. Four business lines, including gaming and professional development, are being spun off. The remaining core activities are now organized in two divisions: the Centre of Early Literacy, which integrates the early English language curriculum with the legacy Amplify insight business, and a significantly narrowed middle-schooled focused version of what was Amplify learning. The business has now around 400 employees. Although the Amplify middle school English curriculum was adopted in California around the time of job purchases, total revenues remain only slightly above what they were when Murdoch bought wireless generation. Losses are expected to continue three more years.

Ironically, it is the effective exit of the two transformational leaders of Amplify—Murdoch and Klein—that creates the opportunity for its future. Well-intentioned revolutionaries can become so singularly focused on where they hope to arrive that they neglect the messy details of how to get there. The inherent complexities and structural aversion to radical change of the educational ecosystem condemn such an approach to certain failure. Jobs’s and Berger’s potential path to success going forward involves a fundamental reorientation of the organization toward the specific incremental needs of the multiple constituencies that drive buying decisions, rather than the general transformational goals of the founders.

The objective of Amplify was to disrupt a wide range of entrenched incumbents operating across the educational value chain. Their failure was a function of a lack of focus and a lack of understanding of the source of the incumbent’s competitive advantage. In the next chapter, a series of investors instead aimed to find hidden value within an entrenched incumbent from a more aggressive operating and acquisitions strategy. The results, unfortunately, were no better.