THE PRECEDING CHAPTERS examined a wide range of high-profile investments in education that ended badly. Not all educational investments end disastrously, though more than their fair share have done so. Before trying to turn these cautionary tales into teaching moments, it is worth standing back and asking, more broadly, which characteristics successful education businesses share. A few attractive education businesses have briefly appeared as supporting characters in the dramas surrounding the failed undertakings that have been the primary focus of this book so far. These businesses will now take center stage, as we examine the key attributes of the most lucrative educational undertakings.

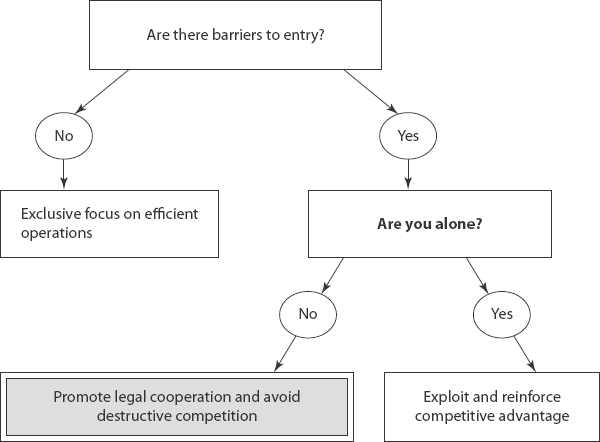

The question of what makes a good educational business is not fundamentally different from what makes a good business in general. Investors who believe there is a difference are likely to experience poor returns. Businesses do consistently well when they can do something that others cannot. Being uniquely positioned to perform a particular activity is unusual but essential for sustainable superior performance. If others can do the same thing, it is a sure bet they will. Performance then, by definition, will no longer be superior. The term for this relatively rare quality is competitive advantage. Although often mistakenly assigned to any number of attractive business characteristics, competitive advantage refers to something very specific: a structural barrier that prevents competitors from simply replicating the results of a successful business.

It should not be surprising that the terms competitive advantage and barriers to entry are interchangeable. Without barriers to entry, a business cannot long enjoy an advantage over competitors that will quickly do the obvious—enter. This process of new entry will hurt not only relative performance but also absolute performance, as competition for customers dampens revenues, and competition for resources raises costs. These generic observations are true for all businesses, but their application in the context of particular industry sectors can look very different. It is not that the general categories of relevant competitive advantage are different. Rather, it is that industry structure determines which categories are most likely to manifest themselves and in what form.

In The Curse of the Mogul: What’s Wrong with the World’s Leading Media Companies, my coauthors and I applied the framework of competitive advantage to the media industries.1 That framework, however, was largely lifted from an earlier work by one of my coauthors, Competition Demystified: A Radically Simplified Approach to Business Strategy, which applies to all industries.2 It is a testament to the consistency of the key categories of competitive advantage that they are so readily adaptable across sectors. In Curse, we broadly defined the media industry as “the production and distribution of information and entertainment.”3 The education industry, however, represents a small subset of the sector so defined—namely, the facilitation of the portion of “information and entertainment” that is directed toward personal or professional development. As this chapter shows, although the key categories of competitive advantage are still the same, important lessons can be drawn from seeing their successful application within the educational ecosystem.

A more detailed discussion of the landscape of competitive advantage can be found in either of the two books referenced. For our purposes, it will suffice to highlight the four sources of advantage most pertinent to education—scale, demand, supply, and regulation and then quickly turn to examples of prosperous educational businesses that have built and continue to reinforce these advantages. These four advantages can all be supercharged by efficient operations, though efficiency does not constitute a structural advantage. Because operating effectiveness—and the absence of it—has played such an important role in the outcome of investments in the educational sector, it is treated separately.

Size Doesn’t Matter, but Scale Does

Michael Milken pursued a strategy of putting together the largest collection of assets dedicated to the increase of human capital. University of Chicago Nobel Laureate Gary Becker, who also sat on the UNext advisory board, popularized the theory of human capital.4 The obstacle to Milken’s success was not any flaw in that theory; rather, it was the fact that human capital is not an industry. Industries are made up of companies related to each other in terms of their primary business activities, not their overarching objective. Amalgamating subscale businesses in different industries cannot establish an enterprise of scale, no matter its ultimate size in absolute terms.

Scale is a relative concept, not an absolute one. The benefits it bestows are relative to peers within the relevant competitive set. No matter how large Edison Schools had gotten elsewhere, no number of private plane trips by Benno Schmidt to Hawaii to establish a beachhead would have detracted from the structural disadvantage vis-à-vis any larger private school networks already operating in Hawaii. Yet, this may not seem obvious—why wouldn’t a global network of K–12 schools be able to do everything cheaper and better than a small but dense cluster of institutions limited to Hawaii? The answer goes to the real source of the scale advantage at the heart of most great historic educational franchises: fixed costs. Scale matters most when fixed costs matter most relative to the business’s overall cost structure. With large fixed costs, the operator serving the most customers will have a significant advantage due to its ability to spread those costs over more unit sales. If the costs of a business were entirely variable and increased proportionally as it grew, there would be absolutely no advantage to scale. The extent of the advantage is determined by how relatively important fixed costs are and how relatively large the business is compared to the next competitor.

The problem with Edison was twofold. First, the cost structure of the K–12 school business is largely variable. The majority of the costs are specific to the individual school—that is, the teachers and staff, the real estate and maintenance, the student materials and equipment. There are some advantages from absolute size— in procurement, for instance, volume discounts would undoubtedly be available on chalk and iPads. And definitely some back- and mid-office functions can and should be effectively centralized. These aspects of the business, however, still represent a tiny fraction of the cost base. Although Schmidt’s outlandish salary was clearly a fixed cost, the private aircraft to Hawaii was a variable cost. Second, much of what is thought of as traditional fixed costs in school management—administration, school relations and lobbying, and even curriculum development—has a significant variable component. It is simply not practical to manage many key functions centrally in a geographically dispersed organization, which is why even Edison established a number of regional administrative hubs to deal with everything from teacher recruitment and relations to marketing to parents and bureaucrats. The staff or consultants Schmidt left behind in Hawaii needed to have local relationships and expertise to succeed.

In the K–12 educational realm, even domains such as curriculum, which conceptually would seem to lend itself to exclusively central investment, actually require meaningful local customization. A major textbook publisher must produce literally hundreds of thousands of SKUs of its core products to respond to local requirements. The impact of the much-touted national “common core” standards initiative has reduced this task, but only at the margin. In fact, after publishers and other curriculum developers collectively invested hundreds of millions of dollars to align their products in anticipation of common core implementation, the political backlash at the state level over a perceived federal takeover of local educational prerogatives has meant that much of those expenditures were wasted.

In recent years, a number of international chains of for-profit K–12 schools have emerged, attracting significant capital from sophisticated investors and high valuations as public companies. Surely, it could be argued, this emergence demonstrates the folly of the assertion that there is little advantage from global, rather than local or regional, scale. Three of the highest-profile international chains are Nord Anglia Education, GEMS Education, and Cognita Schools. A closer look at all three of these businesses reveals the opposite.

Nord Anglia is a Hong Kong–based company that went public in 2013. GEMS is a Dubai-based business, controlled by Sunny Varkey, that recently attracted expansion capital from Blackstone and two Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds. GEMS also had a brief and highly unprofitable association with Whittle (see chapter 1). Cognita—now backed by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, along with its original funder Bregal Capital—started as a roll-up of independent UK schools under the leadership of a controversial former chief inspector of schools in England.

Both GEMS and Nord Anglia offer the International Baccalaureate (IB) course of study to standardize curriculum development across schools in its far-flung operations around the world. In practice, both have had to adopt a variety of other tailored curricula to operate effectively in certain countries. In addition, as Nord Anglia notes on its website, whichever curriculum is being used must be adapted “to embrace local culture and conditions.” GEMS offers eight curricula across seventy schools in fourteen countries. Nord Anglia offers four curricula across forty-two schools in fifteen countries. Cognita, by contrast, though also offering the IB, emphasizes the benefits of a lack of standardization: “Our non-prescriptive, market-driven and agnostic approach to curricula allows us to identify and then invest in any projected imbalance between supply and demand for a curriculum in any market.”5

The most significant commonality among Nord Anglia, GEMS, and Cognita is that their profits all come disproportionately from a small number of countries or regions in which they have a structural advantage, such as scale or a preferred regulatory position locally. When Nord Anglia went public in 2014 for the second time in its history, it touted its global network, even though more than half of its profitability (which was still less than 40 percent of its revenues) came from its operations in China. Until a major acquisition made the previous year, more than two-thirds of the profit had come from China. Thus, Nord Anglia had secured a unique position in the expatriate market (the only potentially available market for foreign operators in China) with multiple schools in the three largest cities and tuition typically paid by employers.

Although GEMS has not gone public, those who have seen its financials note that it generates most of its revenues—and maybe all of its profits—from its base operations in the Middle East. Almost fifty of the network’s seventy schools are based in the United Arab Emirates, including twenty-nine in Dubai, the company’s headquarters. The flagship school there is the most expensive in Dubai, another market with unusual characteristics in terms of a supply/demand imbalance for high-quality K–12 schools serving the expatriate community.6 Similarly, while Cognita operates sixty-seven schools across seven countries in Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, fully forty-three of those schools are in the UK.

The downside of failing to have an adequate local focus is demonstrated in the experience of another international school group, Meritas. After a ten-year global roll-up strategy backed by private equity firm Sterling Partners, it was unable to find a buyer for the entirety of the business.7 In the end, Sterling was forced to sell to Nord Anglia selected assets of Meritas that fit well into its geographic footprint but keep a handful of those that did not.8

The diversity and fragmentation of the private K–12 school market around the world suggests that scale is not the dominant characteristic of these businesses—except potentially within certain narrow geographic niches. By contrast, the U.S. K–12 school textbook publishing has long been dominated by a handful of players. This difference reflects the continuing value of scale in textbook publishing, though that scale is realized on a country-by-country basis due to differences in language, curricula, and distribution channels. An examination of this sector provides a window into the typical sources of fixed-cost scale in education broadly.

Many people seem to think that scale in textbook publishing comes from the actual manufacturing of the product. This thought is not surprising since, as we saw from the story of Houghton Mifflin, many publishers started life as printers. But printing has long been an outsourced function for all the major players. Distribution of books is still undertaken in part by the publishers themselves, with the large physical warehouse and logistical infrastructure a significant source of fixed costs. But even more and more of this facet of the business has begun to be outsourced and, in any case, is not the biggest source of fixed costs.9 The two primary sources of fixed-cost scale in education generally are content development on the one hand and sales and marketing on the other.

Before their combination, Houghton and Harcourt were each spending in the neighborhood of $100 million annually on “plate.” As explained earlier, the combined business collapsed under the weight of the combined cash needs. This did not mean that the combination wasn’t strategically sensible or that there weren’t some genuine synergies in content development that rationalized the combined offerings. Rather it reflected that the combined business had far too much debt and weak operating management. Indeed, the need to relentlessly invest that quantum of capital each year in order to be a credible national K–12 competitor is precisely what has made it such an exclusive club and such a profitable business. Although the nature of the investment has shifted more recently toward software, this shift has not dramatically affected the overall level of fixed costs required to compete effectively.

Given the required recurring investment in product, it is critical for any major publisher to put in place the sales and marketing infrastructure required to most effectively monetize that investment nationally. Even with the adoption of national common core standards, states and localities have additional requirements in selecting a curriculum provider. Although this customization introduces a variable element to cost structure, the commonalities are greater than the differences. Without a national sales and marketing footprint, it is difficult to generate enough sales to justify the content investment. In addition, a well-run organization can leverage its national sales and product expertise to the key levers and adaptations required to compete most effectively locally.

Interestingly, although scale in most K–12 content businesses is defined nationally rather than regionally or locally, it is often defined by discipline or by grade. Certain publishers have particular strength in K–8, while others focus on the higher grades. Similarly, each major textbook publisher has focused on specific subjects that are its forte. When Apollo Global Management (the private equity firm, not to be confused with Apollo Education, operator of the University of Phoenix)10 bought McGraw-Hill Education in a $2.5 billion LBO, the K–12 portion of the business (which was a minority of the overall operation) was actually losing money. Among other things, Apollo identified that McGraw-Hill had felt an obligation to participate across all disciplines and grades, even those in which it was subscale.

After the purchase, Apollo exited those unprofitable pieces and reinvested where the company was a leader, turning the segment solidly profitable. Since the 2012 purchase, Apollo has been able to return its entire original investment, just on the back of the cash flows from the K–12 business. In September 2015, McGraw filed to go public, with Apollo still owning 100 percent of the equity.11 The contrast with Barry O’Callaghan’s financial stewardship of Houghton highlights that the difference between them was not a question of scale. Notably, an even larger LBO of a pure higher education textbook business—Apax Partners’s 2007 $7.8 billion buyout of Thomson Learning—also ended in bankruptcy.12 Although the distribution channel of higher education publishing is completely different, the success of McGraw-Hill Education—whose primary profit source continues to flow from this segment—demonstrates that the problem for Apax was not a lack of scale advantages. Like Houghton, the problem was simply too much debt; it had the wrong capital structure for a business with this level of ongoing and highly seasonal capital requirements.

Scale on the Internet: Network Effects

The initial euphoria around the potential for the digital revolution to quickly expand the reach and effectiveness of educational products reflected a variety of misconceptions regarding the structure of educational markets and the Internet’s economic impact. The Internet radically increases product and pricing transparency for the consumer and can significantly reduce the fixed costs entailed in production, marketing, and distribution for the producer. This is great news for the user; for the operating business, however, the benefits of any reduction in fixed costs are overwhelmed by the increased competition that comes with the corresponding reduction in barriers to entry. As a result, fixed-costs scale—historically the major source of competitive advantage in education—has become less strong and less prevalent than it once was. This does not mean, however, that scale does not continue to be highly relevant. With the diminution of the prevalence of fixed-cost scale has come an increase in the frequency of an entirely different kind of scale: network effects.13

The Internet is itself a network of networks linked by a common language. Although in many instances the killer app of the Internet feels like it is the destruction of competitive advantage, its structure facilitates the possibility of network effects in a variety of contexts that were previously impossible. The benefit of network effects comes not so much from lowering unit costs with every new customer but from every new customer actually making the product better. As a result, the biggest network delivers the best product, which is an inherent characteristic of any marketplace—a new buyer makes it a better place for the sellers, and every new seller makes it a better place for every buyer.14 The virtuous circle of network effects is why eBay has 30 percent margins, whereas straight e-commerce businesses like Amazon struggle to achieve any margin. With every new buyer and seller, the eBay ecosystem becomes more valuable to all participants. Amazon has a traditional consumer retail business model that unquestionably provides a great service, but its value to the customer does not vary in the same way with the number of other users.

Relatively few education businesses have exploited network effects to powerful advantage, though more are emerging to do so. One of the most dramatic and well-established of these is Turnitin,15 founded in 1998 by four University of California—Berkeley students as an online peer review system. Turnitin’s focus shifted, however, to address an exploding problem in both K–12 and higher education. That problem, like its solution, was made possible by the Internet: rampant plagiarism. Developing clever software to detect plagiarism does not feel, by its nature, to be a scale business—whether of the fixed cost or the network effects variety. Indeed, intuitively, one might imagine that a handful of smart coders with adequate caffeine (or harder stuff) could create a serviceable product in a relatively short time. But Turnitin has both varieties of scale in abundance.

The possibility of powerful competitive advantage in plagiarism software is made possible by the way people cheat. If the primary culprit were the copying and pasting of Wikipedia entries, then barriers to entry would be few. In practice, however, cheating in the digital age happens like it did in the analog age—copying off a friend. That said, how you communicate with a friend and what constitutes a friend have changed radically. Craning one’s neck or late-night “study” sessions with a classmate have been replaced with texts and visits to anonymous sharing sites.

The danger of these developments for the detection business is obvious: there is no central repository of the material being plagiarized. But this is where network effects come in. Turnitin is an institutional subscription sale, and all students submit their work electronically for analysis. Turnitin is the sole source of submitted work to compare against other submissions anywhere on the network. Every new institution on the network makes the product better. Current customers have every incentive to encourage their peers to join, which is the best and cheapest marketing a company could wish for.

Luckily for Turnitin, despite its overwhelming relative scale advantage built as it added new clients around the world over almost twenty years, there is still plenty of white space filled with institutions in denial. That space gets smaller with every predictable high school or university plagiarism scandal (or with every scandal involving U.S. presidential candidates or a German minister). Once the decision is made to address the problem, the choice is between the product that has the relevant database to check and a variety of lower-priced competitors that do not.

It was observed that the Internet is generally the enemy of fixed-cost scale economies. Exceptions to this observation are cloud-based distributed software businesses like Turnitin. Unlike traditional software businesses, which require significant variable implementation and maintenance for each customer, software-as-a-service (SaaS) models are much more reliant on central fixed costs. The trick, of course, is to develop a product that gets customer traction quickly enough to establish enough relative scale to have a significant advantage. Turnitin’s continuous software investment since 1998 and its corresponding huge customer base have clearly created a complementary fixed-cost advantage that could not be easily replicated. The net impact is that Turnitin’s profitability is far superior to that of any of the textbook publishers, even in their best years.

A traditional-scale software business but without network effects is eCollege. Developed in the same era as UNext and also targeting the distance-learning market in higher and continuing education, eCollege thrived where UNext failed. By 2007, when it was acquired by Pearson for half a billion dollars, eCollege had become the leading outsourced manager of U.S. distance-learning programs operated by colleges and universities.16

The contrast between UNext and eCollege could not be starker. UNext focused on relationships with highly bureaucratic, prestigious brands that were happy to get “money for nothing” but cared far more about preserving their exclusivity and reputation than about expanding their reach. eCollege focused on relationships with commercially oriented institutions—not just for-profit, but public and nonprofit as well—whose mission was delivering skills to precisely the populations of working adults for whom distance learning provided essential flexibility. “Our model student got home from work, fed the kids, put them to bed and then went to school online,” said early investor and eCollege CEO Oakleigh Thorne. “That created a set of needs that we focused hard on serving, namely the system had to be dependable, it had to be easy to use (even at low connection speeds) and it had to be engaging enough to keep a tired mom awake.”17

UNext structured its institutional relationships with large upfront payments and minimum payment commitments, irrespective of actual enrollments. In contrast, eCollege was structured under long-term relationships, with incentives aligned and payments tied exclusively to the number of students in courses using the platform. Most relevantly, eCollege identified a narrow domain that structurally lent itself to the existence of a small number of industry utilities, which, once adopted effectively, would be costly to switch—namely, a software and service platform on which to run an institution’s distance-learning programs. UNext focused its investment on developing “better” versions of online MBA courses that were already developed by many others and that a long list of newer entrants had also committed to developing. Even worse, rather than using a scale platform like eCollege to deliver the courses, UNext decided to develop its own proprietary learning management system (LMS), which was as foolish as it would have been for eCollege to decide to develop its own courses.

Ultimately Pearson folded eCollege into a new initiative to grab a piece of an emerging adjacent opportunity—online program management (OPM).18 Where LMS providers focus on delivering a scalable platform to institutions, OPM operators are the comprehensive outsourced provider of everything needed to establish an online program other than instruction—not just technology but everything from student recruiting, on-boarding, and retention to sometimes even curriculum development and tutoring.19 Like the original UNext business model, OPMs take a share of the overall tuition bill in return for the services and for footing the bill for the upfront cost of establishing the program—which can run into the many millions of dollars. The attraction of the OPM sector, however, was clear: it was large and growing fast. By 2015, after only a few short years, OPM had established itself as a billion dollar industry with half of colleges surveyed either customers or planning to be.20

Pearson’s commitment to this sector was reflected in the $650 million acquisition of EmbanetCompass in 2012, five years after the purchase of eCollege.21 Growth aside, given the diversity of services provided and types of institutions and programs served, there is at least a question as to whether the OPM sector has the same scale characteristics as the LMS sector. Indeed, a college survey revealed that the industry included not just Pearson, but thirty-five other competitors ranging from established companies to start ups, suggesting that barriers to entry are not high. The anemic level of profits reported, while not dispositive given the early stage and investments required, also gives pause. 2U, an OPM company founded in 2008 that went public in 2014 and focuses on serving elite universities, remains unprofitable.22 Deltak.edu, an early OPM founded in 1997 was purchased by educational publisher John Wiley in 2012.23 Although the business has continued to grow, it was still unprofitable in 2015.

Outside of software, most Internet businesses—both in education and otherwise—do not benefit significantly from fixed-cost scale. However, a number of such businesses in the educational realm do benefit purely from network effects. One exciting early-stage educational business that follows a traditional “marketplace” model is Teachers Pay Teachers (TpT). The business was founded by a New York City public school teacher who saw the benefits of facilitating the sharing of original educational materials among educators. Today, educators not only share but also sell and buy resources, with TpT taking a small fee on any transactions. Although only aggressively developed as an independent business in the past few years, TpT already has 3.5 million active members—about the same number as total K–12 schoolteachers in the United States. Those teachers have already earned close to $200 million by selling their materials on the site.

Many educational investors have lost money following the siren song of getting in early to benefit from the so-called first mover advantage. That advantage, however, does not come from being first—it comes from gaining scale. More often than not, being first is charity work for whoever comes later and is able to take advantage of your generous, free market research. Just ask the unhappy investors in Edison, UNext, or Amplify. The ability to gain scale quickly requires a level of stability in the structure of both market demand and delivery technology. If either is in significant flux, it is simply not possible to gain enough traction to swiftly corner the market. In online marketplace businesses, being first has often—though by no means universally—yielded scale. The basic technology of e-commerce is well accepted; if someone identifies a niche market in desperate need of transparency, the opportunity is there. It is early days, but TpT could be a kind of unicorn upon which venture capitalists should be far more focused—a business with an actual first mover advantage.

Demand Advantages: Keeping Customers Captive

As with all structural advantages, scale can be fragile. A deep-pocketed investor or new potential competitor who sees your success can always try to replicate it to split the market. The most effective way to protect a competitive advantage is to have a second one. All great business franchises have more than one competitive advantage. The competitive advantage most frequently paired with scale is on the demand side of the market—customer captivity.

Customer captivity can be as simple as habit or as complex as the switching costs involved in removing a product that has been integrated into a client’s work flow. It provides important added protection for incumbents in battling insurgents hungry for its customers. A new entrant who is successful at perfectly copying an existing scale business and offering an identical product at an identical price may succeed at splitting new customers, but it won’t get a single existing “captive” customer. Starting a price war won’t help, because all the incumbent needs to do is announce that it will match any price and wait it out.

Every one of the scale education businesses profiled in this chapter has some element of customer captivity. In K–12 textbooks, the state adoption process ensures that, once selected, a publisher is protected until at least the next adoption cycle. In higher education textbooks, the protection for publishers is less formal but even more powerful: just try to get a tenured professor who has been using the same book for decades in an introductory calculus or economics class to change the text used. If a community college has successfully implemented the eCollege platform and is successfully growing the number of distance-learning classes it offers, the potential risks of replacing it with a new platform will loom very large indeed.

A number of the businesses we examined without significant competitive advantages could have been altered to facilitate their development. The core child-care business of Knowledge Universe had little customer captivity—a drop-off center in a strip mall may be the best alternative in a pinch, but it faces significant competition as a longer-term day-care solution—as almost half of the care provided for children up to four years of age is by a family member.24 Even among the less than a quarter of children who are in some kind of center-based care, a variety of public and private options are usually available. The permanently crowded nature of the market and the often ad hoc nature of the need make customer captivity unlikely.

But what if the business model were turned on its head and the customer was an employer under a long-term arrangement to provide employees with a benefit of day care in a facility at or near the workplace? In this case, captivity comes not only from the long-term nature of the contractual relationship but also from the potential backlash from employees if the benefit is removed or if the service provider is switched—particularly given the unique convenience that proximity provides. Starting in 1986, Bright Horizons, founded by a Bain consultant and his wife, pioneered the on-site child-care model. In 1987, the company was one of the first to receive funding from the new Bain Capital and used the capital to build its first twenty centers or so in the Boston area. Bain did very well on its investment when Bright Horizons went public in 1997.25 A decade later, Bain took the company private again in a $1.3 billion LBO, which once more yielded stellar returns when the company went public a second time in 2013.

Although today Bright Horizons operates child-care and early learning centers for almost 150 of the Fortune 500, it took many years for it to secure its current market position. It did so through a combination of consistent organic growth, complemented by acquisitions that cemented regional dominance, established dominance in a new region, or added an important national complementary corporate client base across regions. Although the strongest barriers to entry remain local, the large corporate client focus made a strong national footprint a competitive differentiator in some instances.

In contrast, the first acquisition the Knowledge Universe undertook in this space was called Children’s Discovery Centers of America (CDC), which itself had been rolling up child-care centers since 1983. A few years before Knowledge Universe purchased CDC in 1998, it had acquired a business called Prodigy that specialized in employer-sponsored child-care centers for blue-chip clients like General Motors and IBM. Knowledge Universe could have become the company Bright Horizons is today if it had done fewer acquisitions and focused on this part of the business, instead of pursuing a misguided strategy of trying to create scale and captivity in the part of the industry where structurally little exists. Even after decades of rolling up competitors, Knowledge Universe represents only 2.5 percent of the national child-care market, with dozens of competitors of comparable scale in the relevant local markets. Bright Horizons, by contrast, has 10X the share of the next largest competitor in the employer-sponsored market. Bright Horizons’ valuation was more than three times what Knowledge Universe sold for in 2015.

Renaissance Learning, one of the earliest businesses to introduce technology into the classroom, also came to benefit from intense customer captivity. More than thirty years ago, a mother who wanted to be more involved in tracking her children’s reading skills developed a series of multiple-choice tests based on popular titles by grade level. This became the computer-based reading assessment product Accelerated Reader, which continues to attract a fervent following among educators. Even before numerous studies established the product’s efficacy in increasing children’s interest in reading and skill level, it attracted enthusiastic teacher support because of the “unprecedented level of flexibility, control and time”26 it afforded them.

Renaissance grew through sales to teachers and principals, supported by word of mouth. Its resulting footprint and credibility allowed it to launch not just an Accelerated Math product but also a broader formative reading and math assessment product, called STAR, that is sold primarily at the district, rather than school, level. STAR is now the most widely used assessment in K–12 schools, as the resulting scale across almost twenty million students supports development of predictive models and allows Renaissance to validly norm reference data across an unprecedented number of relevant dimensions and demographics. Teachers usually obtain results in fewer than twenty minutes. The intensity of loyalty to product has resulted in extraordinarily high renewal rates, even during inevitable periods of budget cuts, sometimes supported by heavy lobbying from local Parent Teacher Associations.

Supply Advantages: Leveraging the Learning Curve

The power of habit is such that many incumbent businesses enjoy at least some customer captivity. Alone and without meaningful switching costs, this advantage is unlikely to stand up long to a better or cheaper alternative; in conjunction with scale, however, it can be part of a formidable franchise. It is much more unusual to find corresponding sustainable advantages on the cost or supply side of the education market equation.

Many educational technology products tout their “proprietary technology,” and yet the ability to deliver better and cheaper educational outcomes turns out to be a difficult thing to prove. It is not that all customers wait for proof—in fact, many institutional buyers of educational product appear to be driven by a need to own “the new shiny one.”27 In addition, the speed of innovation is such that, once proven, a plethora of promising and “shiny,” if as yet unproven, alternatives will have emerged. Not withstanding the overblown claims and the challenges of measurement, digital technologies have enabled a much greater level of continuous product improvement of the kind that is a hallmark of “learning curve” advantages.

Businesses that are first down the learning curve are able to deliver superior product for less than those who come behind simply by virtue of their experience. This phenomenon has long been observed in a variety of low-tech businesses, but it is the ability to get continuous user feedback for the first time that has magnified the potential. Google describes learning curve advantages as the “secret sauce” that fills its ever-expanding competitive moat in the search engine industry.28 The so-called data exhaust from educational SaaS platforms is a tool not just for improving the core product but also for strengthening customer captivity. It also often offers the opportunity to build entirely new revenue streams by separately selling the data or building new products on the back of it. Turnitin has benefited from the learning curve in precisely these ways. Its core plagiarism software algorithms are adjusted regularly to reflect institutional feedback. It has also been able to use its data to more inexpensively develop and introduce broader grading and writing effectiveness products.

Like many other buzzwords, however, the promise of “big data” has been far oversold compared with what has been delivered to date. In addition, as Joel Klein painfully learned, privacy and regulatory concerns will continue to be a check on the speed with which the promise can be translated into product. That said, “big data,” particularly within domains in which the breadth and depth of information collected over time demonstrably improves the ability to deliver actionable insights, will undoubtedly move to the forefront of these supply advantages that are still a barrier-to-entry backwater in education.

Not just high-tech pure digital education businesses benefit from the learning curve. A modest student coaching business called InsideTrack has been shown to be remarkably effective at reducing dropout rates at the universities it serves.29 In addition to these results on outcomes, over time, InsideTrack becomes better and better at delivering the same results with fewer and fewer resources. InsideTrack “learns” over time how to most effectively coach students facing the particular requirements needed to thrive at that particular institution. Although other coaching services exist, replacing InsideTrack with another after it has this advantage will be tough—the incumbent should be able to deliver the same or better results for less.

Regulation: We’re Here to Help

The idea of regulation as a potential source of competitive advantage may seem counterintuitive given how much businesses complain about the pervasive influence of government on their operations. A recent survey of more than 1,300 “participants in the education ecosystem” cited regulation at the state and federal level as the first and second largest challenges, respectively, to successful sector investments.30 On closer inspection, however, there is something often quite disingenuous, or at least misguided, about many of these grievances. Meeting regulatory requirements, although a financial burden, often has the effect of protecting scale incumbents from new competition by increasing the minimum level of fixed cost that must be incurred to enter the industry.

Many media industries are built on the back of exclusive licenses provided by federal or local government—the right to use a portion of the federal broadcast spectrum or being awarded a local cable franchise, for instance. Government intervention and oversight in these markets are designed to pursue a variety of public policy objectives, but it can sometimes affect market structure in ways that are at odds with these laudable aims. For instance, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s creation of a limited number of nationally recognized statistical rating organizations was to ensure adequate transparency of the increasing complexity in financial markets. In the end, however, this system merely facilitated the establishment of three mega-agencies with well-documented failures during the financial crisis. The incremental regulations placed on the agencies in the aftermath will have the perverse effect of further entrenching their unassailable incumbent status.

No less impactful is the structure of the current high-stakes state adoption process in K–12 education. Although the large K–12 publishers complain about the huge financial outlays required to participate in these crucial competitions, it is precisely this government-imposed method of selection that has driven the industry’s consolidation. As aggravating as it may be, the fact that there are only three remaining significant market participants, rather than the dozen that operated not so long ago, is certainly a preferable market structure from a shareholder perspective.

The pervasiveness of regulation in the educational sector specifically flows from the simple fact that most of the money feeding the industry comes directly or indirectly from the government. In K–12 education, only about 10 percent of students attend a private school of any kind. Although prestigious private nonprofits may be what come to mind when one imagines the iconic symbols of American higher education, almost three-quarters of students attend public colleges. The balance—both for-profit and nonprofit—rely heavily on access to government funds for their survival. Even corporate training is often the result of specific regulatory certification requirements and is more broadly the subject of a complex web of government incentives.

The largest single chunk of federal government support for higher education comes in the form of loans and grants to low-income students. Although public universities still receive more funding from state than federal government, the explosion in these programs has resulted in federal funding overall now overtaking state funding for the first time.31 These programs underpin access to a college education and historically have been made available to anyone meeting the applicable income thresholds who has been admitted to an accredited institution, regardless of whether it is public, nonprofit, or for-profit.

For-profit colleges have been a part of the landscape since the colonial era and were championed by Benjamin Franklin. Although a founder of the nonprofit University of Pennsylvania, Franklin was a fervent advocate of the kind of practical vocational instruction that would one day be a hallmark of for-profit education.32 Until relatively recently, however, for-profit institutions served fewer than 1 percent of college graduates.33 The modern era of for-profit education is usually credited to John Sperling, who founded the University of Phoenix in 1976 as part of the Apollo Education Group, which he had started three years earlier. Like most of these schools, Phoenix was focused on working adults whose life responsibilities made the rigid schedules of traditional colleges impractical. In addition, initially at least, the University of Phoenix focused on selected vocational programs at campuses in Arizona and California.

When Apollo Education went public in 1994, it was not the first to do so—DeVry University had already gone public in 1991—but it opened the floodgates for a steady stream of IPOs in the sector that continued until the sector’s collapse in 2010. The Apollo offering also signaled the beginning of an unprecedented bull run in the sector over the next fifteen years. At the beginning of 2010, there were more than a dozen public companies with a combined market capitalization approaching $25 billion. By then, the number of students enrolled at for-profit colleges had grown to almost 2 million, from just over 200,000 in 1995.34

This explosion in the number of students at for-profit colleges was not simply a testament to the power of Sperling’s vision. It also reflected a series of government programs put into place beginning with the 1965 Higher Education Act and significantly expanded over the subsequent decades. These programs ultimately made it possible for anyone meeting the eligibility requirements to attend any eligible program at any eligible university using a combination of grants and federally subsidized loans. The result was that a key competitive differentiator became a for-profit school’s effectiveness at convincing prospective students to tap these programs to enroll. The most significant fixed-cost scale advantage from being a large for-profit university had nothing to do with curriculum or outcomes—it was the marketing budget.

The result was that many of these for-profit institutions that once focused on a narrow set of vocational programs regionally now moved into a broad range of general topics, such as business, and sought to establish a national footprint. At the time of the 1994 offering, the University of Phoenix still operated in only six states in the Southwest plus Hawaii; by 2010, however, it was operating in forty states. Notably, although both student enrollment and the number of campuses operated by Apollo doubled between 2004 and 2010, profit margins were actually lower—suggesting limited scale benefits from this unfocused growth.

Aggressive industry expansion efforts were coupled with a variety of aggressive marketing efforts, many of which were subsequently shown to be at least unsavory and, in some cases, illegal. The level of loan defaults rose as student completion rates fell. The beginning of the end came with the announcement in July 2010 of proposed federal rules to significantly restrict the access of for-profit institutions to federal educational programs.35 Although it took years before these rules were actually finalized,36 the impact on the stocks of these companies was immediate. By the time the rules went into effect, enrollments at for-profit colleges had fallen dramatically, with more to come at most of these companies. Apollo’s University of Phoenix, for instance, lost more than half of its nearly half a million students during this time.37 In touting his success in getting the rules put in place over objections and court challenges from the industry, U.S. secretary of education Arne Duncan estimated that another 840,000 students were attending for-profit institutions that would currently fail the standards.

The rules would bar federal funding from programs in which graduates’ loan payments exceed 12 percent of their total earnings. The articulated objective of the “gainful employment” regulations was to protect students “from becoming burdened by student loan debt they cannot repay” and was designed “to complement” a variety of other initiatives to prevent “fraud, waste and abuse, particularly at for-profit colleges.”

Although these public policy aims sound laudable in themselves, two related aspects of this new regulatory regime are worth highlighting. First is that the rules apply exclusively to “career-oriented” vocational programs. Students who decide to pursue a degree in liberal arts—English literature, history, and general humanities remain top choices38—rather than focus on a specific marketable skill face no risk of not being able to use government loans and grants for their chosen institution. They can max out, regardless of their repayment prospects. The notion may be that because these programs do not aspire to provide preparation for gainful employment, they should not be judged by this standard. Interestingly, however, they are not judged by any standard. The absence of incentive for traditional public and nonprofit universities to measure their own performance manifests itself in a complete lack of interest by many in keeping track of any relevant metrics. They focus intensively on the number of applications and “yield” from acceptances, but little after that and almost nothing related to either skills acquisition or postgraduation success. This indifference has a number of follow-on effects, particularly in undermining broader efforts to study the impact of different pedagogical approaches. For example, one of the biggest problems in conducting research on the relative effectiveness of MOOCs is that there is no baseline to which it can be compared.

It would be wrong to conclude from this narrow focus, however, that the government is hostile to vocational training. Indeed, the recently announced proposal to make community colleges—the historic focus of which has been career-oriented training—absolutely free suggests quite the opposite.39 Notably, if community college were free, the gainful employment regulations would never apply to their vocational programs, because there would be presumably no debt required to pay tuition. This fact foreshadows the second anomaly in the rules: they simply do not apply to public and nonprofit institutions (which together make up around 90 percent of U.S. college student enrollment) in the same way. Unlike for-profit universities, associate’s and bachelor’s degree programs at these schools are exempted from the gainful employment rules. Only their certificate programs are subject to the same review.

An argument can be made that for-profits have earned this heightened relative scrutiny. After all, almost half of student loan defaults are from students at for-profits. The government points out that the average tuition at a two-year for-profit institution is four times as much as at a public community college.40 But the very fact that for-profit enrollments exploded in the face of this overwhelming price disadvantage suggests that maybe something is wrong at community colleges.41 Although unsavory marketing practices certainly played some role, it is hard to believe that for-profit’s responsiveness to the complex needs of this difficult-to-serve population was not a critical element of their growth. The data in fact suggest that student completion rates at community colleges are actually lower than for similar programs serving comparable student populations at for-profits.42 Although it is true that default rates are much higher at for-profits, this is not that surprising given the relative price and resulting debt load. In addition, from a taxpayer perspective, it probably doesn’t matter much whether their money is being wasted through direct state and local subsidies to bad public community colleges that keep the price low or through indirect federal subsidies to fund tuition for bad for-profit universities. The real question is how to most effectively—from both a cost and outcomes perspective—serve these nontraditional students.

Notably, when the gainful employment regulations were finalized in 2014, a key requirement of earlier draft proposals was mysteriously dropped. Under previously circulated draft regulations, schools would also be judged by an independent standard related to the frequency of student loan defaults. When pressed for an explanation for dropping this requirement, the government said, unconvincingly, that it was looking to “streamline” the regulations. For-profits, however, suspected that “the change was mostly about protecting community colleges,” whose students consistently fell afoul of the rules despite having much lower borrowings.43 What’s more, the gainful employment calculations are made only for those who actually graduate, creating a potential incentive to encourage those considered likely to harm the statistics to drop out (much like the charge that charter schools manage low performers out to show high average test scores44).

Regardless of how one feels about the wisdom of the current approach to for-profit regulation, from a public policy and industrial logic perspective, the correct answer is the same: consolidation. From a public policy perspective, having the better-run schools buy the weaker-run schools would seem the most effective way to improve program effectiveness. Such combinations have the added advantage of providing continuity to the existing student populations. From an industrial logic perspective, the increased regulatory burden adds significant fixed costs of both tracking and reporting. The increasing importance of technology—both for compliance and for delivering hybrid and full-distance-learning programs—also heightens the central cost requirements. In addition to the resulting advantages of absolute scale, certain combinations would provide scale in regional geographies or specific degree programs, where one or another of the institutions lack the needed heft to be competitive.

Unfortunately, the new rules have resulted in transactions of very different kinds: bankruptcies, restructurings, go-privates, and reorganizations from for-profit to nonprofit simply to avoid the application of the rules. Corinthian Colleges, with 72,000 students, filed for bankruptcy. Education Management Corporation (EDMC) succeeded in restructuring its debt out of court but quickly announced plans to close a quarter of its Art Institutes.45 Grand Canyon University is the largest for-profit so far to look to change its status to nonprofit to avoid the additional regulatory scrutiny.46

The lack of significant strategic combinations is a function of a number of obstacles. Chief among them is the lack of any mechanism to obtain prior approval from the U.S. Department of Education to ensure continued eligibility for federal programs after the ownership change. Some believe that the government’s failure to facilitate sensible combinations is a function of its general hostility to the for-profit sector. Indeed, as a practical matter, most well-run schools would be loath to take on the regulatory risk to their existing business of becoming associated with a poorly run one, even if they were in a position to meaningfully improve its performance. Former university president and U.S. Senator Bob Kerrey charged that the government’s “incoherent public policy” in this regard “betrays a bias against private enterprise.”47 These critics view the regulatory initiative as driven not by a desire to improve vocational education opportunities but by an ideological desire to have public community colleges replace the entire for-profit industry. If this was their hope, the data are not encouraging. For-profit enrollment fell by more than 500,000 between 2010 and 2015, and community college enrollment fell by almost as much.48 Indeed, the data suggest that when he leaves office in 2017, Obama may become the first president since data began being collected in 1869 to have presided over a decline in total enrollments at degree-granting institutions.49 More disturbing given the policy objectives is the fact that the declines have been greatest among low-income students.50

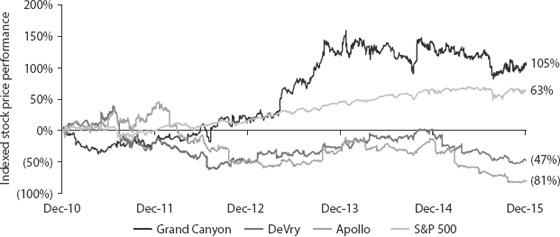

Regardless of the motivations and justifications for the radically changed regulatory landscape for for-profit higher education, it is worth looking at which for-profit educational institutions have performed relatively well in the face of it. In short, the institutions that have best averted the extended sector downturn are the niche players who stuck to their respective defensible market positions. Notably, they resisted the temptation to be all things to all people and avoided pressure to pursue growth at all costs.

All of the public for-profit universities lost between almost 50 percent and close to 100 percent of their value during the five-year period ending at the start of 2016. The sole exception is Grand Canyon University. The other distinguishing characteristics of Grand Canyon are that (1) it is the only for-profit that eschewed geographic expansion, and (2) it boasts the highest operating margins in the sector. The school has the same single base campus in Phoenix that it began with in 1949, when it was founded as a Christian university. Today that campus has grown to 205 acres from the original modest facility. The school has also leveraged its full-service campus—including a Division I sports program—serving 8,200 traditional students to build a highly profitable business serving more than 50,000 evening and online learners. This approach has made the business significantly less reliant on government aid programs than the for-profit peer schools because of the parental support afforded traditional on-campus students. In addition, the Christian affinity represents a psychographic niche within which it is less costly to build scale and strengthen captivity.

Figure 5.1 Grand Canyon University indexed stock price performance, five years ending December 31, 2015

Data Points: Grand Canyon University, DeVry University, Apollo Education Group, S&P 500

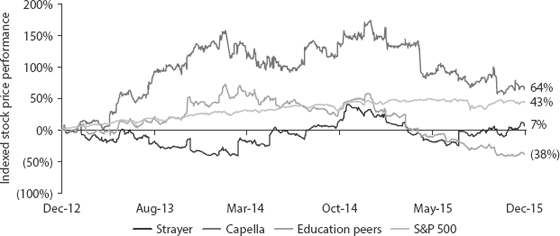

More recently, two other institutions also stand out: Strayer University and Capella University (see Figure 5.2). Along with Grand Canyon, these are the only major public for-profit universities whose revenues are actually anticipated to grow in 2016. Strayer has managed to stabilize enrollments, even as the rest of the industry has continued to decline significantly. It has tied its business model to corporate partnerships and has established relationships with community colleges. The corporate relationships strengthen the stability of enrollments and the likelihood of “gainful employment.” The community college relationships are the kind of legal cooperation that minimizes destructive competition, improves the nature of possible integrated offerings available for students, and inexpensively expands Strayer’s footprint.

Figure 5.2 Strayer and Capella Universities indexed stock price performance, three years ending December 31, 2015

Data Points: Strayer University, Capella University, Education Peers, S&P 500

Capella is a pure distance-learning provider that has long focused on a narrow range of graduate degree programs in high-demand sectors. It has actually reversed enrollment declines and returned to levels above those achieved in 2010. Capella has avoided the certificate courses that have been a mainstay of the original explosion in for-profit enrollments generally. The school’s online programs attract students with a significantly higher probability of completion. Founded in 1993 by the former president of Central Michigan University and the former CEO of Tonka, the company went public in 2006 and, in 2007, received the National Centers of Academic Excellence in Information Assurance Education designation from the National Security Agency.

Even in the ashes of the restructuring of EDMC is further evidence of what makes a good education business in highly regulated markets. The company’s first acquisition was of the fifty-year-old Art Institute of Pittsburgh in 1970. Although the strategy of focusing on a vertical subject expertise by leveraging an established local franchise made sense, the mismatch between the cost of delivering a high-quality product on the one hand and the attractiveness of employment opportunities in art and design outside selected major markets on the other doomed the aggressive national expansion in the face of gainful employment rules. The jewel in EDMC ended up being an entirely unrelated business acquired in 2003 called South University—a regionally focused provider of degrees in a wide range of health-related professions with a heritage dating back to 1899. South grew largely by launching new schools in the region and expanding the accredited health-related programs it offered, up to the doctoral level in some cases, in areas such as nursing, pharmacy, physician assistant, and health sciences. Although enrollments at the Art Institutes, which by then numbered in the many dozens, began to decline precipitously in 2010, South’s enrollment has increased since then, with strong profitability well above that achieved by any other part of EDMC.

Although South represents a solid franchise, there is no evidence that it was made more valuable in EDMC’s hands. South simply continued to operate independently under Chancellor John T. South III after the acquisition. The error in EDMC’s strategy was not the acquisition of South in itself, but the fact that the transaction was part of a much broader effort to simply get larger as fast as possible. For the twenty-five years leading up to its IPO in 1996, EDMC had added only eight art schools. It had instead focused on building and investing in the existing core franchise. The same year that EDMC purchased South, it also bought the far more generic American Education Centers, with eighteen schools scattered among far-flung states and offering a wide range of business programs. Changing the AEC schools’ names to Brown Mackie College the following year did not make the business any more compelling.

From its IPO as a focused, well-regarded art and design school in fewer than twenty markets with less than 25,000 students, by 2010 EDMC had become the second largest for-profit, with more than 150,000 students around the country. By aggressively exploiting the unfettered availability of federal student grants and loans, EDMC rapidly built absolute size without reinforcing actual scale in more durable relevant market segments. The result was a missed opportunity to use the extended period of misguided regulatory largesse to build a more sustainable franchise.

Operating Efficiency: Running It Well

Across industries, the performance gap between best and worst in class is massive. For all the rhetoric about the potential productivity gains from the introduction of new technologies, the reality is that over any reasonable time horizon, these could be dwarfed by low-tech operating improvements. Just bringing industry laggards up to the standards of industry leaders represents low-hanging and plentiful fruit.

Strategy is about reinforcing competitive advantages. Operating efficiency is about performing optimally with or without barriers to entry. In businesses without competitive advantages, superior operations are the only way to deliver superior performance. In businesses with competitive advantages, efficient operations can provide a multiplier effect to the superior returns afforded by industry structure, just as inefficient operations can be a powerful impediment to superior returns.

The strategic importance of efficient operations is that even the most seemingly insurmountable competitive advantage is not forever. When strong barriers to entry become weak or nonexistent, the lack of a culture of efficiency leaves a business dangerously exposed. This is precisely what happened in the newspaper industry, when the Internet robbed the sector of its wildly profitable classified advertising franchises. Generations of indifferent management made the resulting transition much more wrenching than it needed to be. Newspaper proprietors, with very few exceptions, have largely become observers in the transformation of the broader news and information sector as they have played catch-up and focused on internal restructuring that should have been undertaken years earlier.

Contrasting the performance of Nobel Learning over time—both before and after the installation of CEO George Bernstein and before and after Milken’s ownership—demonstrates the potential power of operating excellence. Nobel itself is in the school and preschool sectors, both of which have modest barriers to entry. And yet, the business has managed to combine these businesses in a way that strengthened the operations of both. When Bernstein took over from CEO Jack Clegg and his family-dominated management team in 2003, the stock had fallen since Milken had first invested, delivering a meager annualized return of 3.5 percent since its IPO. This result was achieved during a period when the overall stock market had delivered greater than 10 percent returns. Bernstein quickly exited a number of noncore ventures and implemented a variety of retail-like processes to streamline operations. In addition, he closed underperforming schools and organized the business in critical mass clusters—adding both organically and inorganically to optimize the footprint—under regional managers.

Almost half of the cost structure of these businesses is local wages. From a revenue perspective, the key to effectively managing schools—both preschools and K–12—is to ensure that those personnel (and the facilities they are working in) are being optimized. A few points of capacity utilization can make the difference between a poor and a satisfactorily performing facility or between a good and a great one. It is here that Nobel really excelled in designing its product and targeting its markets.

On the product front, Nobel provides a wide variety of services under the moniker of “early learning”—everything from essentially babysitting for toddlers to a serious nursery program for four year olds. Bernstein invested in developing a branded curriculum—Links to Learning—that goes from six weeks to kindergarten (five years old). Parents are given monthly reports highlighting progress across key developmental stages. This approach keeps the family engaged and justifies refusing to accept children on an ad hoc, drop-off basis as opposed to committing to a schedule that permits effective curriculum delivery. In addition, by eschewing government support and focusing on educated families with a median income around $150,000, the business avoids the operating challenges associated with managing transient populations and volatile funding regimes.

Furthermore, Bernstein instituted best practices on the teacher training and development front that have yielded high Net Promoter Scores and parent satisfaction rates—critical in a market where 60–70 percent of customers come from local word-of-mouth referrals. Among the early innovations was an intranet portal for sharing lesson plans across the network, not unlike what TpT has built. The combined impact of a high-quality, integrated product and corresponding payment plans structured to encourage student continuity has resulted in lower customer “churn” than in typical child-care settings. This, in turn, supports meaningfully higher capacity utilization.

Although operating K–8 schools and child-care centers is not intrinsically synergistic, the Links to Learning curriculum feeds into the core curriculum of the early years at the elementary schools. About half of Nobel’s revenues are from clusters of stand-alone preschools; the other half comes mostly from linked clusters of preschools and K–8 schools. All the Nobel K–8 schools benefit from a significant percentage of their enrollment coming through the linked preschools, which supports their capacity utilization as well. Notably, each cluster typically operates under its own, often long-established local brands rather than under the Nobel banner.

From the time that Bernstein joined the business until the buyout, the share price grew at a compounded rate of 12 percent, even as the stock market was growing at just 2 percent. As mentioned in chapter 4, however, the real benefits came once Milken exited and Bernstein was able to focus exclusively on operations rather than governance.

Growing and Protecting the Franchise

Having a good education business is one thing; keeping it good and growing it is another. Often, however, protecting and further developing the franchise are deeply intertwined activities. Defending and growing both require the same activity: investing.

The key to smart investing is a keen sense of the specific source of competitive advantage that supports an enterprise. Investment in growth is only good for shareholders when the expected returns are greater than the corporate cost of capital. It is only in the face of a barrier to entry—that is, an ability to invest in an opportunity not open to others—that investment results excel. It may be that all children in Lake Wobegon are above average, but corporate investments in the absence of competitive advantage are destined to just be average.

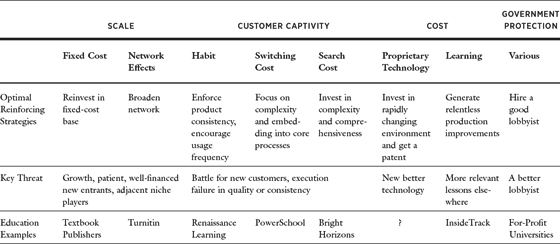

Having a barrier to entry is a necessary but not sufficient condition to being better than average when it comes to investing for growth. Simply spending more—particularly on venture investments or entirely new business lines designed as a “hedge” against risks to the core business—should not be expected to yield superior returns. It is only when the investing specifically reinforces an existing advantage that others cannot follow suit. Possible, but much more rare, is the situation in which aggressive early investing allows the establishment of an advantage—typically, scale—where none existed before. The critical point, however, is that different competitive advantages are bolstered by different kinds of investments (Table 5.1).

TABLE 5.1

Sources of competetive advantage

Economies of scale are reinforced by investing to ensure that relative scale is maintained or extended—whether reflected in the size of the customer base over which fixed costs are being spread or in the size of the network that delivers superior value to participants. Fixed-cost scale is also enhanced by continually raising the ante in terms of the extent of fixed costs that need to be incurred to play. Aggressive investment in product research and development is a key fixed-cost category, but so are lower-tech functions, such as the sales infrastructure.

Many acquisitions are justified based on the ability to deliver scale. These scale advantages can result in real “synergies”—both cost synergies from eliminating duplicative fixed infrastructure and revenue synergies from selecting the most productive infrastructure to keep and leveraging that across the entire combined business. But whether such synergies actually deliver benefits to the shareholders is a separate question. If multiple strategic suitors would benefit from the same synergies, however, it is likely that competition will force the winning bid to price in all of the potential synergy value created in the winning bid. The only circumstance in which the buyer will be able to retain some of this value for itself is when either the buyer is uniquely positioned to benefit or when the other similarly situated competitors have some constraint—financial or otherwise—that impedes their ability to participate. As an example, if an existing K–8 school becomes available in an area where Nobel has a cluster of preschools, then Nobel is uniquely positioned to pay the top price while still retaining benefits for its shareholders. However, when a textbook publisher outbids all the other textbook publishers for a synergistic product or service, it is likely that very little of the strategic benefits will accrue to its shareholders rather than the sellers.

Customer captivity comes in a variety of flavors, and the investments required are distinct, if sometimes related, for each. Habit is enhanced by frequency of use; switching costs, by integrating product into the customer work flow; and search costs, by providing a uniquely comprehensive suite of products. As Coca-Cola learned the hard way with its 1985 introduction of New Coke, product consistency is critical for maintaining all manner of customer captivity. The art of building the moat is to make continuous improvements that are subtle enough to not rock the captivity boat.

In education, the subsector that exhibits the strongest customer captivity is the market for student information systems (SIS). A public school system of any size simply cannot operate without an SIS, which serves as a central data repository for managing everything from student grades, assignments, attendance, and scheduling to all the school’s core daily operating activities. The importance of an SIS relates not just to its role in ensuring effective operations; it is also essential for being able to satisfy the myriad regulatory requirements of the many federal, state, and local authorities that provide funding.

The PowerSchool Group, founded in 1997 as the first web-based platform, is the largest SIS, with more than twice the market share of its nearest competitor—giving it scale as well as captivity. In any given year, however, due to the power of all the dimensions of captivity, very few customers are in the market for a new SIS. Renewal rates at PowerSchool average 99 percent, and the balance of the industry is not far behind. The PowerSchool Group achieved most of its market share the old-fashioned way: it bought it.

In 2006, Pearson bought both PowerSchool, which had been owned by Apple for the previous five years, and Chancery SMS (another SIS that focused on large urban districts) and combined both with its existing system. Although all new sales are made on the PowerSchool platform, such is the importance of consistency to maintaining customer captivity that Pearson never pushed its Chancery customers to migrate to PowerSchool. A decade after the acquisitions, almost two million students remain on Chancery. Although financially “inefficient,” the decision reflected Pearson’s appreciation of the true source of competitive advantage and the sensible desire to not make PowerSchool the New Coke of the SIS market.

Cost advantage is most frequently best pressed by hurtling down the learning curve. Although obtaining truly proprietary technology that provides a sustainable cost advantage is rare, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try. Indeed, the process of continuous technological improvement and investment helpfully increases the fixed-cost table stakes, regardless of whether a defensible proprietary technology results.

Regulation in education is pervasive but also highly unstable. Local and national preferences shift with the political winds, making it dangerous to count on a specific regulatory regime or funding paradigm to permanently buttress a business model. From for-profit colleges to online charter school managers, the thrill of government largesse and protection can quickly be overwhelmed by the realization that the business is going down the drain once the authorities decide to pull the plug.

Lobbying can be money well spent, but it is often money badly spent. Given the inherently volatile nature of politics, if it is the only money being spent, the benefits of regulatory advantage are likely to be short lived. The trick is to use the temporary protection of government to build a more permanent moat that will survive regime change. Just as a studio executive spends his days scheming to stay on top, while simultaneously planning for life after his inevitable downfall, a business built on the back of a specific government program, contract, or law must prepare, from its earliest days, for an afterlife.

Contrast Wireless Generation, which never managed to turn the windfall of the New York City ARIS contract into a commercializable product, with SchoolNet’s ability to leverage its early relationship with Philadelphia into a business operating well beyond “the city that loves you back.” Similarly, Strayer’s aggressive partnerships with private businesses as a central part of its business model explain its relatively muted recent enrollment declines, as compared with Apollo, in the face of the dramatic changes to the federal rules. Or consider that the fastest-growing and most profitable part of Nobel, a company that generally eschews any government ties, is the white labeling of its online Laurel Springs AP classes to private schools—a market that K–12 should have cornered long before Nobel had a chance.

Even when the regulatory framework endures, it is often the other structural competitive advantages built up behind it that drive long-term value. In the case of the ratings agencies, the initial government designation allowed them to build scale so that, if the government now allowed anyone to issue ratings, it would make no real difference to the strength of the core franchises. Similarly, the scale that Grand Canyon built around its core geography and demography will endure in a way that those for-profits that simply sought to grow enrollment at all costs will not.

Cooperation Without Incarceration

Reinforcing and growing barriers to entry must not be undertaken in a vacuum. As many sources of competitive advantage as a business may be blessed with, nothing is forever. The aim should be to ensure that the full potential benefits of competitive advantage are enjoyed and that they endure as long as possible. These objectives are not in conflict, but they do require a willingness to temper any testosterone-fueled inclination to destroy all competitors and ruthlessly press an advantage against customers and suppliers.

The two theoretical extremes of industry structure are intense competition among many competitors with free entry and exit and a single dominant player whose competitive advantages are so many and so profound that none dare challenge. The former yields relatively modest returns for even the best operators, whereas even the slothful may enjoy great bounty in the latter environment. Far more typical, however, are industries in which a handful of participants have roughly comparable competitive advantages vis-à-vis all others. How an individual player fares in such circumstances will be driven not only by their operating prowess but also, and more important, by how they decide to interact with their peers. More than anything else, how market leaders with shared competitive advantage manage competition among themselves determines whether the industry thrives or suffers. The decision to engage in no-holds-barred, hand-to-hand combat across every potential dimension of competition is unlikely to deliver world domination to a single victor. Rather, prolonged, shared misery—akin to life in sectors without any barriers to entry—is the almost certain outcome.