“Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.”1

—JOHN DEWEY (SORT OF)

THE FINAL YEARS of the twentieth century witnessed a surge of interest from a veritable who’s who of investors, entrepreneurs, academics, and policy makers who all had the idea that education could be dramatically improved by implementing radical new business models. Some of this euphoria coincided with the first Internet boom, during which many traditional ways of doing things were thought to face imminent obsolescence. In the case of education, however, the intensity of conviction was bolstered by a belief in the power of applying market disciplines to a sector that often seemed to shun them on principle. Technology might accelerate the coming revolution, but it was new big ideas about education that fueled it.

And money. Lots of money.

The billions of dollars that had and would continue to flow into education were unsurprising given the stakes involved. The overarching objective, according to the New York Times, which closely chronicled these developments, was no less than to “turn the $700 billion education sector into ‘the next health care’—that is, transform large portions of a fragmented, cottage industry of independent, nonprofit institutions into a consolidated, professionally managed, money-making set of businesses that include all levels of education.”2

In this environment, the initial public offering (IPO) of Edison Schools on November 11, 1999, was a signal event. Edison represented the powerful proposition that a private company could deliver better public schools for less money, leaving taxpayers, investors, and children better off. With ambitions to operate a thousand public schools, Edison would represent less than 1 percent of all public schools, but its impact could be far broader. If successful, Edison could establish a standard of excellence by which all schools would then be judged and to which they would aspire. As founder Chris Whittle predicted, “Ten years from now, when you think about who does the best schools, we want there to be only one word that quickly comes to mind.”3

It wasn’t that the offering was particularly successful by traditional criteria. The shares were priced at $18, below the original proposed range, and they barely budged once trading began. By contrast, many of the eighteen other NASDAQ IPOs of that week experienced the kind of explosive value bump typical of the era’s technology offerings. But Edison was definitively not a technology stock. It did, however, have one important characteristic in common with many high-flying technology offerings of the era: it did not and had never made money. In fact Edison, founded in 1991, around the time the first webpage was created and well before the Internet was commercialized, had managed to lose money for far longer than any of these public market darlings.

The Edison IPO represented the establishment’s embrace of the notion that education was poised to be revolutionized for the better. Merrill Lynch, a long-time leader in equity underwritings, managed the offering.4 The investors represented the best in breed of individual and institutional investors. Paul Allen, who had recently invested $30 million, was not just the legendary cofounder of Microsoft but also a leading Silicon Valley venture capitalist. Just that week, he had been involved in two other successful IPOs—Expedia and Charter Communications.5 The leading commercial bank, J.P. Morgan, and the leading bank to growth companies of its day, Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, were also investors.6 John W. Childs, who had engineered the wildly successful leveraged buyout (LBO) of Snapple as a senior executive of Thomas H. Lee Partners before founding his own buyout firm, was an early backer, as was the Wallenberg family investment vehicle, Investor AB. The company had also attracted the president of one of the oldest and most prestigious educational institutions in the United States, Yale University, to serve as its chief executive officer (CEO).

On November 12, 2003, shareholders voted overwhelmingly to sell the company for less than a tenth of the $18 per share paid in the IPO four years earlier. The very public collapse of Edison did not, however, dampen otherwise sophisticated investors’ enthusiasm for transformational educational concepts. Indeed, if anything, the flow of capital into the education sector has accelerated in the decade since the first Edison debacle, though often with similar results. As the activity level has increased, the high caliber of the backers for these enterprises has held steady—encompassing the top echelon of financial institutions, wealthy individuals, corporate sponsors, private equity, sovereign wealth, venture capital, and even hedge funds—as have the dismal financial outcomes.

The stories of financial failure that follow are filled with the names of individuals and organizations whose successful financial exploits in other domains have defined the era. The strategic vision of billionaire moguls Rupert Murdoch and Ron Perelman shaped both the structure of the global media industry and the art of deal making. John Paulson’s hedge funds made $15 billion in 2007, predicting the coming financial collapse. Michael Milken may still be controversial, but few question the transformative impact to the economy of the financial instruments he popularized and the markets he developed. The world’s leading investment banks—not just J.P. Morgan, but also Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, and many others—certainly generated fees from the sector but also lost hundreds of millions from a combination of bad investments, loan defaults, and ill-conceived underwritings. And the long list of multibillion-dollar private equity and sovereign wealth funds that have continued to fare poorly in education represent some of the most storied names in a sector whose influence on global financial markets is unprecedented. Might their collective fate provide clues to the seemingly intractable challenges facing education more broadly?

Introducing the subject of education is like administering a political Rorschach test. Questions of educational policy elicit intense reactions on a wide range of emotional hot-button issues, from unions to affirmative action to the gap between rich and poor. More than thirty years after the publication of the landmark A Nation at Risk7 report by the National Commission on Excellence in Education, education has seemed to remain in perpetual crisis. Warring constituencies find little common ground on the nature of the problems, much less their solutions. If there is any consensus, it is that things are not getting better. Whether it’s school children’s falling rankings internationally in math, reading, and science proficiency or the lack of preparedness of our college graduates to enter the workforce, these fundamental deficiencies have only become more pronounced. From time to time, a shining example of isolated success—whether a student, an educator, a program, or an institution—is held up, only to be contrasted with the inadequacy of everything else.

The persistence of these disagreements reflects the extent to which our approach to education as a nation implicates how we think of ourselves as a people. At the most basic level, the American identity as the land of opportunity is deeply intertwined with how educational opportunity is made available.

American exceptionalism, in education at least, is not a myth; rather, it is grounded in the reality of how the country came to be. American’s peculiar attitude toward education was central to Alexis de Toqueville’s coining of the concept of “exceptionalism” in Democracy in America. “From the beginning,” wrote de Toqueville, “the originality of American civilization was most clearly apparent in the provisions made for public education.”8 Providing basic education to all was viewed as an essential element to building the anti-aristocratic society the early settlers envisioned. In fact, these fiercely independent Puritans were happy not only to collect taxes for this purpose but also to enforce payment and actual attendance through fines and even the potential deprivation of parental rights.

The ideological tinge to the current educational debates reflects this combination of historical and contemporary controversies that lie just beneath the surface. Into this witch’s brew of themes and concerns are inevitably added deeply personal considerations. The formative experiences of being educated leave an indelible mark. Every successful person has at least one oft-replayed story about that teacher or that course or that administrator or that institution that made a difference—whether good and bad—in his or her life.

These education-related turning points in individuals’ lives may have very little to do with pedagogy or policy. The teacher who took a lonely and isolated child seriously. The book that spoke to a long-held secret. The class in which you met your first true love. The psychological lives of young people grappling for a sense of identity in the face of a vast menu of new experiences and emotions are complicated. What actually serves as a transformational catalyst in a particular case is impossible to predict in advance and almost as hard to accurately diagnose after the fact. It is unavoidable, however, that these epiphanic moments are, to some extent, generalized and incorporated into one’s views on education.

These multiple sources of interest explain only in part the intensity, ubiquity, and nature of the various ongoing political and intellectual debates on educational matters.9 The rest of the explanation is just how much money is now involved. Roughly $1 trillion annually in the United States alone, the sheer volume of public expenditure on education ensures that it will be the subject of heated combat among and between groups focused on minimizing taxes, getting funds, and using the services.

The massive pool of government largesse flowing to education takes the form of everything from teacher salaries and capital investment to student loans, veterans’ benefits, tax deductions, Head Start, and school nutrition programs. With this much at stake, education cannot help but be a high-profile issue. There is a political multiplier effect, however, when matters of money—particularly enormous quantities of money—also implicate matters of principle and personal identity.

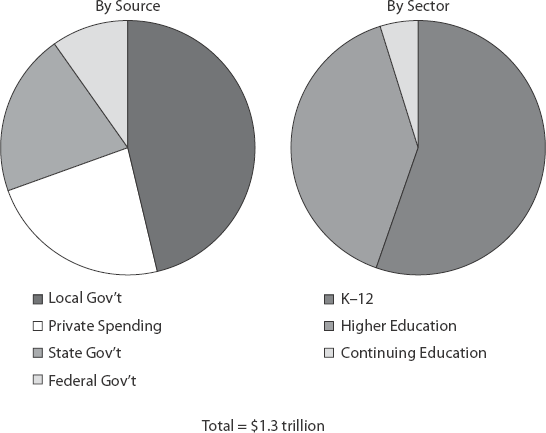

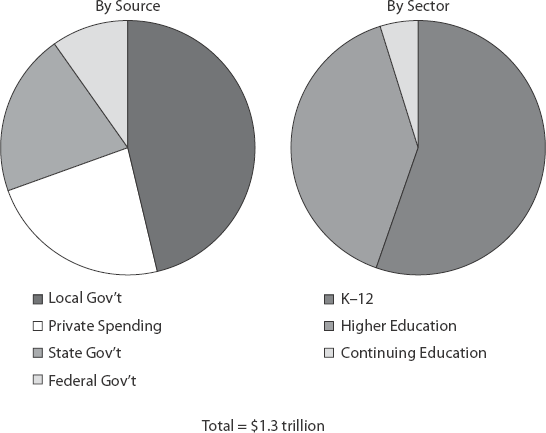

Figure I.1 2015 U.S. education spending.

Sources: U.S. Census; U.S. Department of Education; BMO Capital Markets.

Outside the government sphere, the flow of private funds has grown dramatically. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is the most well known of a cadre of foundations that have become major consistent sources of educational funding. For the past decade, a combination of established funds like the Ford Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation have joined newer organizations like the Broad Foundation and Lumina Foundation, along with multiple locally oriented education foundations, to invest $4–$5 billion dollars annually into a mix of public, nonprofit, and for-profit educational ventures.10 In addition to private institutional funding, rich individuals have increasingly become enamored of the idea of making a difference in education. Having a building or a program named at one’s alma mater is a long-established practice, but recently, charter schools and education policy advocacy groups have become the charity of choice among a large swath of hedge fund billionaires.11

If education is failing, it is not for lack of money or attention. Our greatest minds and our deepest pocketbooks seem committed to making it better. How can we reconcile this depth of commitment to improve things with the apparent inability to do so?

The passions elicited by educational topics have proven a double-edged sword. Passion ensures enduring focus, but can also color perspective and generate a level of conviction that the facts do not support. Passion can lead to an embrace of simplistic, all-encompassing explanations, whereas the reality is all nuance. Passion can take the well meaning down dark alleys paved by less-well-meaning suitors who exploit emotional weakness.

When brilliant, rich, passionate people disagree, reaching quiet resolution is an unlikely outcome. In educational matters, where the debate is on matters of principle and the data are often ambiguous and subject to multiple interpretations, progress is even harder to come by. There is no agreed measure of success, except at the very highest level of abstraction—that is, “improved student outcomes,” which becomes the subject of intense debate when actually defined. The frequent lack of consistent, transparent, timely data on educational effectiveness exacerbates the structural obstacles to consensus. Even the policy implications of widely available basic metrics, such as test scores (are the right things being tested?) or graduation rates (are the graduates actually prepared?), are the subject of heated controversy.

The story of Edison Schools reminds us that, outside of academia, the public sector, and the nonprofit world, there is a thriving marketplace for educational ideas, where success and failure are not subject to debate and can be measured quite precisely—in dollars and cents. Some of the most respected minds of our generation have invested many billions of dollars in for-profit education enterprises. And, with surprising regularity, they have lost their shirts.

No less a personage than Steve Jobs spent most of the time between his two stints at Apple trying to transform education with Ross Perot’s money (and when that ran out, with Canon Corporation’s money). After more than a decade, the company (NeXT) created some interesting software, but it was a disaster commercially and had no appreciable impact on the education market.12

The simple idea of this book is that by highlighting where these otherwise accomplished individuals went demonstrably wrong, we can identify a number of common errors that have undermined progress in education. These mistakes have often flowed from a basic misunderstanding of the education ecosystem specifically and the importance of industry structure more generally. Collectively, the lessons drawn provide guardrails that can help not just investors and businesspeople but also policy makers and administrators avoid some of the more treacherous and persistent pitfalls.

The book is organized around four extended case studies from which the core lessons emerge. The ability of Chris Whittle to repeatedly raise money for questionable business propositions more than a decade after the unambiguous failure of Edison reflects a self-destructive tendency of education investors to cling to misguided convictions in the face of contrary evidence. The good intentions of Rupert Murdoch and Joel Klein in trying to revolutionize how our children learn led them to irrationally discount the increasingly high probability of disappointment as their plans soured. The failure of a string of investors to appreciate the costs and risks of creating educational content, as well as of the need to continually refresh it, is a key factor in the serial insolvencies undergone by storied publisher Houghton Mifflin. The fate of the vast array of unconnected educational ventures backed by Michael Milken was sealed by his lack of appreciation for the critical role of specialization in building financially robust educational businesses.

These four case studies are followed by a number of contrasting profiles of successful educational ventures. The book’s final chapter explores in more detail the recurring themes embedded in the recounted tales of financial success and folly, including those lessons just noted and many others.

There are disadvantages to using cases from the for-profit sector. Although it is true that it is relatively easy to identify whether someone made or lost money, this is different from determining whether their pedagogic objectives were achieved. We all know that “bad” products sometimes seem to make lots of money. That said, every educational business plan is built on assumptions about how students learn, how teachers teach, and how decisions are made about what products and services to use. They also rely on a view of the education ecosystem’s structure and on locating a position within it that permits the establishment of a sustainable competitive advantage. When those plans miss the mark, particularly on a grand scale, important lessons can be learned about which specific underlying assumptions were misplaced.

More important, even when an enterprise is nonprofit in nature, it is necessary to appreciate its place in the overall industry structure in order to assess its long-term viability. Nonprofit businesses often rely on the ability to continue to attract government and private funding. A miscalculation of the capital needed can be as deadly to its survival as running out of money is to a for-profit educational business. Understanding the key drivers that enable the development of sustainable educational business models is as critical to building enduring nonprofit enterprises as it is for building enduring for-profit enterprises. So although the case studies employed here are all from the for-profit sector, in which the bottom line can be clearly assessed, they are designed to enable both for-profit and nonprofit enterprises to better identify the structural imperatives that will facilitate their survival—a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for making a positive contribution to education.

There are other, more fundamental objections to using financial profit or loss as a relevant metric for education. Some express deep ideological hostility to the very existence of for-profit educational institutions. For-profit primary and secondary schools have always faced opposition from those concerned with the historic equalizing role of public schools, the impact on teacher unions, and the increasing gap between rich and poor. For-profit universities have been viewed with similar derision by those who view these institutions as opportunistically exploiting government’s abandonment of its responsibility to support a strong network of public community colleges. The recent scandals around widely publicized abuses of the federal loan programs by for-profit universities have provided compelling fodder for those who hold these views.

Even the loudest proponents of public education, however, do not object to the for-profit nature of the educational enterprises that make up the majority of the sector. For-profit schools represent an increasingly small percentage of the total revenues of the vast web of private enterprises engaged in educational endeavors. These enterprises produce everything from the textbooks and software that provide the teaching materials to the testing and assessment products that monitor the results to the technologies that assist communication and decision making across every element of the learning cycle. Literally thousands of businesses big and small exist only to support the activities of not just educational institutions but also the training and development efforts of the corporate sector. In any case, philosophical hostility toward for-profit education should not extend to the possibility of gaining insight from the ashes of their efforts.

An altogether different and more practical objection to focusing on for-profit education is that it just doesn’t matter that much in the scheme of things. Educational spending overall is overwhelmingly dominated by and directed toward public entities. Of the estimated $1.3 trillion expected to be spent on U.S. education in 2015, mostly from government sources, less than 10 percent will go to the for-profit education sector.13 That said, the $125 billion in revenues expected to be generated by for-profit education is still an awful lot of money. Furthermore, as noted, understanding the key structural, strategic, and operational considerations that make the difference between successful and unsuccessful education businesses is equally relevant to nonprofit education businesses. Most important, however, is the central role played by the pervasive government regulation of the sector. Without an understanding of the key drivers of private-sector behavior, the public sector cannot hope to structure an effective regulatory regime for whatever objectives it is pursuing. A partnership between the public and private sectors in education based on mutual understanding could create a virtuous circle in which both are strengthened. In practice, however, that interaction has yielded a vicious cycle in which regulations have resulted in outcomes contrary to those intended, precisely because of confusion regarding underlying industry dynamics—only to prompt yet more regulations that only exacerbate the problem.

In addition to highlighting the key structural attributes of educational business, the cases used for this exercise were selected, in part, to reinforce an overarching theme: educating students presents a diverse and complex set of challenges that do not lend themselves to a single set of easy solutions. Like all “big” social questions, such as crime and poverty, the gravity of the issues involved cry out for a simple comprehensive strategy that quickly yields meaningful improvements. Yet, this idea lends itself to grand-sounding initiatives—whether a “War on Poverty” or “No Child Left Behind”—that inevitably fall short.

The historical evidence is that, time and again, the greatest successes come from a series of targeted incremental steps forward that confront, one by one, the full variety of problems to be addressed.14 This book’s objective is for the lessons outlined to provide such incremental benefits, rather than an overarching “solution.” Conversely, based on the evidence presented here, the biggest failures in education come from trying to do too much, too soon. Pursuing “revolution” or “transformation” by blindly applying insights gained from a particular context across a broad range of only tangentially related situations is likely to do more damage than good.

This book examines three broad domains of education (Table I.1): (1) education through high school (generally called K–12 education, but also encompassing prekindergarten and early childhood learning15), (2) colleges and universities (called higher education), and (3) continuing adult learning (whether independently undertaken or as part of corporate training efforts). Some of the case studies focus on a single domain: Both Whittle and Murdoch, for instance, were preoccupied exclusively with K–12 education. Michael Milken, by contrast, had multiple investments in each of the three domains.

TABLE I.1

Summary of education sectors ($ in billions)

| Sectors |

Total Spending 2015 |

For-Profit Revenue 2015 |

Estimated Annual Sector Growth 2015-2020 |

Key For-Profit Subsectors |

| K–12 |

$745 |

$45 |

2.7% |

Childcare/early learning; For-profit schools; Textbooks/supplemental publishers; Testing and assessment; Professional development; Learning management system; Enterprise management system |

| Higher Education |

$530 |

$65 |

3.4% |

For-profit universities; Curriculum/textbook developers; Student lifecycle services (e.g., admissions, retention, placement); Learning management system; Enterprise management system |

| Continuing Education |

$65 |

$15 |

3.9% |

Instruction-led training; E-learning train-ing/certification; Content developers; Plat-form/infrastructure developers |

| Total |

$1,340 |

$125 |

3.3% |

|

Source: BMO Capital Markets

Within each segment, there remain critically important distinctions—for example, the challenges of teaching advanced placement calculus to gifted high school students is very different from selecting the best manipulatives for a kindergarten class. However, there are two important reasons to treat K–12, higher, and continuing education separately.

First, from an economic perspective, the nature of who businesses sell to in each of these arenas is fundamentally different. This, in turn, has a profound impact on the most effective organization of the businesses and their basic business model. K–12 sales are generally made to governmental entities, school districts, or sometimes even states that formally “adopt” particular products, often on a long-established, multiyear schedule. Higher-education sales are more ad hoc and are generally made either to individual institutions or to individual teachers who are typically free to decide what products to use in their classes. Continuing education is often sold directly to consumers or to the corporate human resources divisions of for-profit enterprises. Given these important distinctions, it is not surprising that many of even the largest educational companies operate primarily or exclusively in only one of these education realms.

Second, from a public policy perspective, the most contentious issues are also quite different in different domains—as are the nature of the resulting regulations that constrain the operations of these businesses. This, in part, relates to where the money comes from—K–12 funding is predominantly a state and local matter, whereas higher-education funding comes primarily from a combination of federal, state, and private sources. Continuing education has less direct funding but is sometimes the subject of various tax incentives. More fundamentally, however, the issues at stake in educating the very young, those preparing for a career, and those looking to upgrade their existing job are viewed very differently. Even when the same issue is raised, it would not be unusual or necessarily inconsistent for the same person to have a very different reaction depending on the context. For instance, many who are happy to have tenure at universities abhor it in their local public schools.

Just as K–12, higher, and continuing education broadly support different types of business models, so too do traditional publishing, software, and services businesses. The largest educational publishing businesses are multibillion-dollar enterprises that, in some cases, are more than a century old and have shown modest growth in the face of changing business models, though they often still generate prodigious cash flows. The software and technology businesses that have sprung up over the past decade have, in many cases, grown quickly and garnered outsized attention relative to their size and profitability. These include a wide range of digital content, analytics, learning and administrative management, and distribution businesses. The business of actually providing educational services in direct competition with incumbent public and nonprofit private institutions has proven, as noted, the most controversial of the for-profit enterprises.

Whatever one thinks of these endeavors, understanding their underlying economics is still useful. Many of the largest educational enterprises now encompass a portfolio of businesses that reflect most, if not all, of these potential modalities. In general, however, a single business model still predominates. All of the educational publishers have launched a variety of software businesses, and some actually now operate schools of their own. In addition, certain for-profit universities have purchased educational content businesses. Sometimes these expansions reflect a natural extension of the core, and sometimes they are just an effort to hedge the risk in the core. In selecting cases to examine, I chose examples of each of these types of businesses to highlight the key distinctions in both the underlying business models and the expansion strategies.

Each case explored in this book tries to tell a story. Sometimes the protagonist is a person—perhaps an investor or a business leader—and sometimes it is the product or business itself. The stories also represent a mix of fundamentally bad businesses, blindly pursued, and potentially good businesses that were poorly run or wrongly capitalized. In all cases, money was lost, sometimes quite a bit and sometimes repeatedly. This kind of track record tends to elicit an instinctive search for villains. Readers may spot a few within these pages, but it is a surprisingly small number given the magnitude and circumstances of the losses. In most cases, despite the fact that these are for-profit ventures, the individuals involved appear to have been motivated, in part, by a genuine desire to improve education. That desire is often associated with a deep-seated belief about what is wrong with the current system. The moral of these tales is how the intensity of desire and belief can cloud the judgment of even the most sophisticated investor.

Brilliant, rich people with a passionate emotional commitment to an idea not only have trouble responding to rational debate, but they also, unfortunately, have a tendency to attract con artists, the best of which instinctively know what story to tell and what information to feed a mark so committed to an idea that they will fail to verify claims. It is sometimes hard to distinguish a crook from a true believer. The narratives presented here try to stick to facts and withhold judgment. I would suggest, however, that the most probative evidence is to what extent the money lost is one’s own or others’.

At the end of the day, the underlying motivations of the various actors matter less than knowing how to avoid the mistakes detailed here. The trick is to retain the passion for education but lose the emotional or ideological commitments to particular solutions. When it comes to educating future generations, the stakes are indeed high. As investors and as citizens, the downside of letting ourselves be conned is substantial, regardless of whether we are being tricked or we are simply fooling ourselves.