porcelain rooms, porcelain cities

i

It is eighteen miles from Meissen to Dresden and for Augustus the great joy of having his own manufactory so close, is that he can wave his hands, bring ideas into shape, order gifts for the congeries of people who shift and clog every entrance to the court. And because the king collects, his courtiers collect too.

The money remains complicated, of course. There are Chinese vases that he wants from the collections of Frederick William I of Brandenburg and Prussia, over three feet tall, made and decorated in blue and white in Jingdezhen. They are not for sale, which makes them irresistible. So in 1717 he conjures a plan to exchange these vases for a battalion of 600 dragoon soldiers, pots for people. These soldiers have crossed over from Saxony at Baruth. Each monarch declares that this is a gift and no money passes hands. The eighteen vases that formed the centrepiece of this exchange become known as the Dragoon vases. The battalion take the Meissen cipher, the two crossed swords, as their banner. The soldiers become the Dragooners.

With the quantities of porcelain arriving here, where and how Augustus displays his porcelain in his city becomes an imperative.

I’m listening to court music from Dresden on my headphones as I walk through the city and there is a phrase played on an oboe that keeps being picked up by the violins and taken out and aired and then given back. And what I hear is a sort of return to structure, the singular becoming clearer and then becoming plural and hidden, and then re-emerging. In the beautiful phrase of the American philosopher John Dewey, describing art as process is like the flight and perching of a bird. You are in it. Then you pause and see what it is. And then back to absorption, the flight of music.

This is at work with the feeling for how porcelain phrases build up into complex melodies, while bringing you back to single pots. This is still a recent idea as Augustus starts to arrange his great collections in Dresden, find ways of animating the thousands of vessels he is buying, the thousands he is commissioning from Meissen.

Porzellankabinette, porcelain rooms, have currency in courts and palaces across Europe. The late English Queen Mary employed a young Huguenot architect, Daniel Marot, to create rooms at Hampton Court and at Kensington House. He has style of the more is more kind: his beds finish in ostrich plumes, his surfaces oscillate like the breathing flank of some thoroughbred animal. Chimney pieces were covered in porcelain garnitures, dishes and small vases were on brackets on every wall, pots lined the architrave where the ceiling started its curve. In his engravings Marot shows shafts of sunlight coming in, mirrors and lacquer panelling adding to the theatre, hundreds of pots becoming endless chambers of thousands.

This manner of displaying porcelain became hugely popular, much to the fury of Daniel Defoe. ‘The Queen brought in the Custom or Humour as I may call it, of furnishing houses with China-ware which increased to a strange degree afterwards, piling their China upon the Tops of Cabinets Scrutores and every Chymney-Piece to the tops of the Ceilings and even setting up Shelves for their China-ware, where they wanted such Places, till it became a grievance in the Expence of it and even injurious to their Families and Estates.’ This seems an excessive reaction, until I remember that Defoe has some knowledge of clay. He is the owner of a failing tile works in the Essex marshes, put out of business by the Dutch. Grievance is a good word, for Defoe, policing other people’s extravagance.

For these rooms embody excess. At Charlottenburg in Berlin Frederick I created a room for Sophie, Leibniz’s correspondent and the clever one in the marriage. Here it is so layered that porcelain is not only reflected in mirrors but recedes into the walls. There are jars in front of dishes resting on brackets on glass, niches running round the room for tiny pots, painted Chinese figures with dishes as hats. Images weave across different dimensions.

Augustus has seen how other rulers use porcelain and is dismissive. He remembers his visit to the Trianon de Porcelaine at Versailles almost forty years ago. What is the point of having a pretty little pavilion sitting damply in your parkland to show your visitors, or a room somewhere up near the library or a music salon with some rows of vases on the chimney piece? It would look like you had used up all your porcelain!

So the work has started on Augustus’ Japanisches Palais across the Elbe. It is vast. The roof of the palace sweeps down like a pagoda. You enter through a great gateway and see a courtyard beyond you. All the columns are held up by crouching oriental figures. The toes of their sandals sweep up. You go right up a run of shallow steps, and when you reach the first floor, you will be in a long room which contains nothing but the beautiful red and brown Jaspis porcelains from China and Japan. And then the double doors at the end will be thrown open and you will enter a room furnished entirely with celadon porcelain. And on. Through blues and greens and then purples. Through different colours and patterns of porcelain, each space opening on to the next. It is a fugue state, a journey through the spectrum of porcelain. You end up either in a chapel of white porcelain or a small and perfect space of white and gilded porcelains. It is music.

The Japanisches Palais is to be the greatest building of porcelain since the emperor Yongle ordered the pagoda in memory of his parents three hundred years ago.

Augustus orders a painting showing ‘Saxony and Japan who quarrel over the perfection of their porcelain manufactories … The goddess [Minerva] will graciously bestow the award of the struggle into Saxony’s hands. Jealousy and dismay will prompt Japan to load their porcelain wares back on to the ships that once brought them here.’

I remember that early in his porcelain madness, Augustus dreamt of sending ships to the Orient – Japan or China – to buy up what he could. It is different now.

ii

On my final day in Dresden the temperature drops even further. As I’ve never been inside the Japanisches Palais, I make an appointment. The porcelain is long gone. Thirty years after Augustus died the great displays were stripped back, room after room of different glazes and patterns, and moved to the cellars. In the 1860s, ‘duplicate’ porcelain was sold or swapped. The French porcelain manufactory of Sèvres did really well out of this trading. An educational museum of ceramics was planned. It never happened.

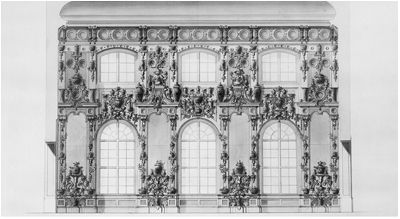

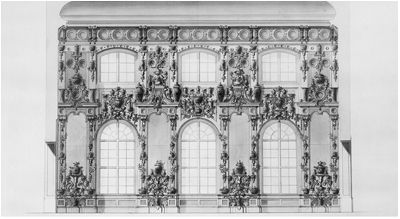

Design for the Japanisches Palais, Dresden, 1730

I get stuck here, thinking of the breaking up of Augustus’ collections, wondering why ‘duplicate’ should have been a problem, as duplication, multiplication was the only imperative in his life.

The palais has been home to the coin collections, to the antiquities collections, the state library and for a hundred years, an ethnographic museum and geological museum have been here too. It has been a Dresden lumber room. And it is now almost deserted. Most of these ethnographic collections have gone, off to a new museum in Chemnitz. Three white vans are parked aslant in the great courtyard. A few lights are on. A conservator comes to meet me. She has been working for eighteen years on a decorated, panelled wooden room from Damascus, bought a century before, dismantled and stored, forgotten as objects and collections came and went, shipped to the fortress at Königstein during the Second World War, retrieved. It is a room of perfect proportions, to sit in and talk, Arabic poetry on panels high up, painted cartouches of fruit amongst the flowers.

The poetry, she says, was chosen so that it would offend no one who came, Muslim, Christian or Jew.

And in her vast workshop overlooking Dresden, the rooms of the palais that used to be the rooms for celadon porcelain, with half-conserved panels on the floor, she brings out small cakes, makes green tea and serves it in glasses.

I couldn’t get to Damascus, but I realise that Damascus has come to me. We talk about porcelain and she finds photographs of great dishes of Chinese blue-and-white from Jingdezhen displayed in rooms in Damascus and Aleppo, waiting to be taken down, placed on these carpets of flowers, heaped with pilafs, shared with family, guests, travellers.

iii

It has taken me over twenty years to get here to the palais.

I had an ink sketch of one of these rooms pinned up above my wheel for a very long time. It was a challenge. Did I want to make porcelain that could be shuffled around, or could I make more of a demand on the world, shape a part of it with more coherence?

I made my own porcelain room for an exhibition at the Geffrye Museum, a kindly brick-built eighteenth-century almshouse on a grim and busy road in the East End of London, now a museum for the history of the domestic interior. Another artist, a maker of baroque and highly coloured ceramics, and I were each given a space and a modest budget. I said yes on the turn of the conversation. I reckoned that the last porcelain room had been commissioned towards the end of the 1770s, a mirrored room of porcelain confectionery, spun in gilded nonsense for some Italian palace.

I wanted to be able to feel what it was like to be surrounded by porcelain. It was a stage set in MDF, rather than marble, in a temporary exhibition space in the basement rather than overlooking a deer park, or the Elbe. But theatricality was part of every porcelain room ever built. And this felt fine.

For it to be a proper room I needed a wall and a floor and a ceiling and light. The wall was 400 cylinders, each four inches high on fifteen shelves. Repetitions and returns as clear as any bit of Philip Glass piano music. On the floor were black industrial bricks. I put seventy shallow dishes into a thin channel, a line of grey porcelain inlaid into the ground like a sustained note.

Light came in through a porcelain window. I’d thrown huge cylinders, trimmed them as thinly as I could and cut them into panels. I dried these very slowly between boards and fired them with trepidation over several days. Then I held them up to the light. They worked. They were translucent; light filtered through, just. It was a sort of dusty, slightly yellow creeping kind of light, but lucid. I saw my hand through my material, darkly.

And I made an attic.

Attics are places where you try and forget. They are stuffed with cast-offs, broken toys, places where you store the things you cannot legitimately dump – wedding presents, children’s drawings, abandoned musical instruments, suitcases that might come in useful for some over-specified holiday that isn’t going to happen. And they are places where the most valuable things go.

But in my porcelain room I wanted a place for the ideas that haven’t been completely realised, working notes, marginalia, drafts crossed out. Why would I want to keep this? Not for authority, but rather for the humanity of it, the crunch of shards in the yard of the workshop.

So, I put a garniture and some lidded jars and a line of pots that I’d tried out on the shelves before realising their proportions were slightly clumsy, and they looked beautiful in the shadows above me.

Beautiful because you cannot see them in their entirety, pinned down and accessible. They were safe, I suppose. Not safe from being handled, used, but safe from being got at and documented and sold. It is not that being shadowy gives you gravitas or mystery, or that you are clothed in some borrowed seriousness. Rather, shadows push profiles away. You can gain the shape of an idea by losing its particulars.

We had an exhibition opening about which I can remember very little except that my little boy of three adored the room next door with its pineapples. And that one person after another after another told me how frustrating it was not to be able to see what was in the attics. Why weren’t they lit?

This was my transitional moment as a potter. I now made Installation. I hovered excitingly near to Architecture.

And I heard Grievance.

iv

I’m racing again. I know I should be calmer, but calm and this strange city are not aligned for me. I have no time left. I have so much to see again. I need to check the colour of the celadon wares that Augustus commissioned for the Japanisches Palais so I run back across the Augustus Bridge, turn right and run through the courtyard of the Zwinger.

I catch my breath in the porcelain galleries. They hum gently as visitors admire the exhibits.

These spaces were never intended for porcelain. They weren’t used for this until the Soviet Union shipped back the treasures of Dresden, taken to Moscow for fraternal safekeeping in the days following the entry of the Red Army in April 1945.

In 1958, Augustus’ porcelain returned – mostly – alongside the other great objects from the Kunstkammer. The Zwinger, in ruins from the bombing, began to be restored and in 1961, it was reopened.

I range back and forth. The galleries are magnificently wrong. Garnitures of Kangxi famille rose from China and Kakiemon from Japan sit on giltwood tables. There are fragments of ‘porcelain room’ display in the niches, plates and vases on brackets in perfect symmetry. Some of the Dragoon vases are here on a plinth. There is the model of Augustus the Strong on horseback. This was the subject of endless despair. How can you make a sculpture in porcelain where horses’ legs can support a figure? One huge room of these galleries holds the menagerie of porcelain animals, created over twenty years by the great sculptor Kändler, displayed on a rocky outcrop under a bell tent of swagged silk. The alarm goes off every ten minutes as someone tries to get close to one of the huge porcelain figures of the rhino or the lion.

There are vitrines for some of the famous dinner services – the Swan service made for Count Brühl, where the pellucid plates are modelled so that fish and birds seem to emerge out of water. There are coronation services and marriage services, and the whole unfolding of Meissen as Everything. Porcelain for harlequins and bands of musicians, fountains and ruins for table decorations, candelabra, crucifixions, busts, cutlery, walking sticks. Porcelain for tribute and gift and diplomacy, for display and for intimacy. And painted with classical scenes, and landscapes, and phantasmagorical creatures and butterflies, birds, insects. The celadon wares flare up on a wall. They are bluer than I remembered them.

There are helpful cases for comparison, and the wall texts are terrific, and clear. Lifetimes of scholarship and connoisseurship are here. And it is not that I’m expecting authenticity – great dinner services on tables a hundred feet long, the menagerie lit by candles, though that would have been a nice touch – it is just that it seems so tame.

It has been admired so much that it has expired, grandly. The fierce, brilliant, terrifying idea of white has been smothered. Tschirnhaus has disappeared, gilded.

Porcelain has become bourgeois. It becomes my eight-lobed bowl, fat with summer fruit. It becomes the ‘gilt-edged Meissen plates’ brought in carefully by the servants under the sharp eye of the mistress of the house during an endless dinner of fish and boiled ham with onion sauce and desserts of macaroons, raspberries and custard in Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks. It becomes expensive and collectable. It is here that porcelain becomes possible for many things; it is re-inscribed as a commodity rather than a princely secret. This particular rewriting should feel fine. After all, each piece of porcelain in the collections has its cipher, a reign mark from China, or a factory symbol and its inventory number, and many renumberings. Every document seems to be annotated. When I go back to the great first notebook entry of porcelain being discovered, album et pellucidum, I realise, painfully late in all my research, that it is not only Böttger’s handwriting on the page but that someone else has written up the notes too.

This whole city is a palimpsest. There are contemporary restorations of GDR rebuildings of the palaces and treasure houses destroyed in the war.

As I leave the Zwinger through the archway under the Stadt Pavillion I notice a plaque on the left commemorating its rebuilding with the help of the Soviet Union. It is undated. But there is a footnote, a smaller plaque, also undated, which tells you that the original is from 1963.

This, I think, must be early Post-Wall Confidence, 1990.

In the taxi to the airport I chat to the driver about the Lebkuchen and Stollen that I bought last night at the Christmas market, and she tells me that the market was not good. The proper one is elsewhere. I always seem to get markets wrong.