i

In Stoke-on-Trent, Josiah Wedgwood is in his pomp. His creamware has taken England by storm. After years of methodical testing he has discovered ‘a Good wt. [white] Glaze’ that works with his beautifully constituted earthenware. His new ware is finely made, can stand the shock of boiling water, and is contemporary in its clean colour. It is ‘Ivory’, he writes. He has delivered the first set to Queen Charlotte, who has graciously allowed it to be named Queen’s Ware. ‘How much of this general use, & estimation, is owing to the mode of its introduction - & how much to its real utility & beauty?’ he asks in a letter, reflecting happily on ‘how universally it is liked’.

He hurdles problems and anxieties. This week – a week of fair March weather in Plymouth – he writes: ‘Don’t you think we shall have some Chinese Missionaries come here soon to learn the art of making Creamcolour?’

He is like Augustus the Strong goading the Japanese to come up the Elbe and load up with Meissen.

China Earth from America has piqued the interest of Wedgwood who seems, I am finding, to be both omniscient and omnipresent.

Wedgwood writes to his business partner Thomas Bentley that:

I find that others have been dabbling with it before us, for a Brother of the Crockery branch call’d upon me on Saturday last and amongst other Clays he had been trying experiments upon, shew’d me a lump of the very same earth which surprised me a good deal and I should almost have thought myself robbed of it if it had not been much larger than my pattern. He told me it came from South Carolina.

Decisive, he puts a plan together to send a man to the scarcely accessible mountains to get him some tons of this clay, to possibly buy the mountains themselves. This white earth is perplexing, but Wedgwood is not a man to be held back. He has the self-confidence to consult and take advice.

He looks at maps, at Hyoree, Ayoree, Eeyrie, somewhere. Taking out a patent is a form of madness as it will clag him in lawyers and parliamentary shuffling and show his hand to other potters when getting the stuff dug out of the mountains is the imperative. This is an annoyingly slow and expensive imperative as he finds that the earth must be carried nearly three hundred miles overland ‘which will make it come very heavy’.

It is now May and he has to arrange the new showrooms in Pall Mall and ‘Vase madness’ means whirling requests and decisions. What do you do if you need something in a hurry? You find the right man. He is recommended Thomas Griffiths, a man who ‘is seasoned to the S. C. Climate by a severe fever he underwent at Chs. Town & has had many connections with the Indians’. He is down on his luck and ready to travel. Terms are agreed.

Everyone, I realise, comes to Wedgwood first.

A French nobleman, Louis-Léon-Félicité, duc de Brancas and comte de Lauraguais, has been in Birmingham chivvying Erasmus Darwin. He ‘offere’d the secret of making the finest old China as cheap as your Pots’, Darwin reports to Wedgwood.

He says the materials are in England. That the secret has cost him 16,000£. That he will sell it for (2,000). He is Man of Science, dislikes his own Country, was six months in the Bastille for speaking against the Government, loves the English … he is not an Imposter. I suspect his scientific Passion is stronger than perfect Sanity.

The news gets to William Cookworthy a little later. An old friend has told him that the comte has spent a fortnight sniffing around Scottish granite, a substance not far removed from moorstone, and has been pushing hard for a patent for porcelain.

When I read Wedgwood’s letters, I think of him and all the great princes and their chamberlains and decrees on the decisive ordering of porcelain. I go and see the French nobleman’s beautiful plate in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It shows an insouciant butterfly, barely able to make it across the pearly French porcelain sky. And I see the Cookworthy brothers, the chemist and the sailor, opening up their Trifle of a kiln in the garden at Notte Street and gingerly passing their slightly damaged Idea backwards and forwards.

ii

It is June and we’re in Plymouth.

William’s new porcelain venture needs investment and a patent. Everything will be ready in a month. ‘Thou will be pleased to take the Town Attorney’s Opinion about this matter.’ William and Champion take their time and get the lawyers in. It is a classic start-up.

The house and pit for washing the clay has been honestly executed. The bricks from Bristol have arrived for the kiln, the mason has cut and polished the stone for the mill to grind, a ton of pipe clay to make the roughly thrown saggars is on its way. William has taken ‘a part of the Cockside Storehouses Sufficient for the Carrying on of Our Experiments, tis the most Convenient Spot for the purpose about our Town’. It is six guineas per annum.

It is now July. On the 16th, the seasoned Thomas Griffiths pays seven guineas for passage and one pound ten shillings for a cabin, and boards the ship America to sail across the Atlantic to find and then buy white earth from the almost inaccessible mountains of the Cherokee nation. And bring it back. He arrives in Chas’ Town Bay on 21 August – a miserable, hot and sickly time – to start his journey into the nation of the Cherokees.

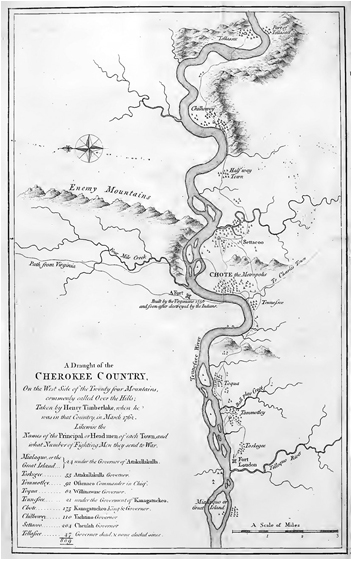

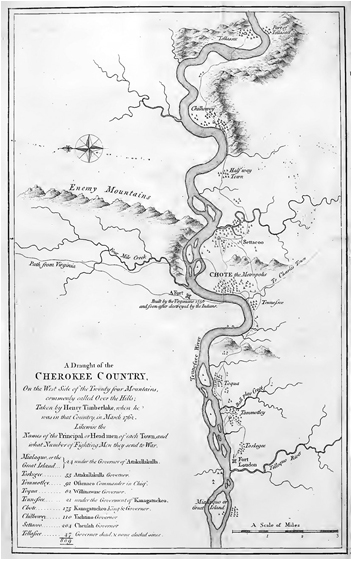

Map of Cherokee country, 1765

This stretch of country is beyond any law. It is six years since the end of the Cherokee War and there are hunters and unpaid militiamen and displaced settlers in the backcountry. The ragged new settlements, an inn of sorts, a blacksmith, hovels appear, sketchily, amongst the black oaks, hickory and ash. You look after your horse well, keep travelling and you keep your wits with you.

Griffiths buys three quarts of spirits, a Tomahawk for twelve shillings and sixpence, and sets out. He falls into conversation on the road with another trader, a rare sight as you can travel for thirty miles without seeing anyone. Two days before a set of thieves, ‘the Virginia Crackers and Rebells’, had robbed and murdered five people, just here. Carry your pistol in your hand, now, he tells Griffiths, there are ‘two fellows ahead that he did not like well’. His companion advises don’t stay in that house, stay outside; ‘the people were all sick and lay about the rooms like dogs, and only one bed amongst ’em’. If you wake up, your horse will be gone. Griffiths buys ‘corn for my horse and potato bread and a fowl for myself, which I boiled under a pine tree, near the house, where I slept part of that night’.

It is now September. Griffiths journeys towards the white earth: progress slows in Plymouth.

William has wildly underestimated the difference between making a test with his brother in the backyard and real production. He describes it and it is like seeing the Industrial Revolution in very slow motion.

In Plymouth, the arch of the kiln has come down:

in the Course of the experiment, which prevented the Fire from reaching the top of it … We were also unfortunate in the bottom of our Safeguards cracking by which means the powder of Spar which keeps the vessel from sticking fell down into the Bottom of the vessel under it … We shall set about Repairing our kiln tomorrow … I have no Question but we shall do very well in this way too whence we come to make an object of it.

The test pieces were cold and rather grey. They looked slightly, unpleasantly, viscous, like the bloom on the barrels of mackerel. It is porcelain, no doubt about it, but who would want this Cornish version? It rings alright, a relief after the dull timbre of the last pieces, but I pause here and register that they are making shards, day after day after day.

On 17 September, Griffiths joins up with an Indian woman belonging to the chief of the Cherokees. He arrives at Fort Prince George, the first settlement in the nation, about forty miles from the Indian Line.

His luck is in. He has arrived just as ‘most of the Chiefs of the Cherokee Nation’ have gathered to choose delegates for a peace conference with the ‘Norward enemies’.

Griffiths writes:

after I had Ate, drank, smok’d and began to be familiar with these strange Copper Coloured gentry, I thought a fair opportunity to Request leave to Travill through their Nation in search of anything that curiosity might lead me to; and in particular to speculate on their Ayoree white earth. And accordingly the Commanding Officer … desired to be very particular on the subject. This they granted, after a long hesitation, and severall debates, among thoughtfulness some more seem’d to consent with some Reluctance: saying that they had been Troubled with some young Men long before, who made great holes in their Land, took away their fine white Clay, and gave ’em only Promises for it.

Suddenly you are there, listening.

You hear that you are not the first. So who has been before? And when? Promises have been made, and promises broken. And then you hear anger and then anxiety. They do not care to disappoint as you have come in good faith, openly, but ‘they do not know what use that Mountain might be to them, or to their Children’.

The moment lightens, passes. Their white clay will make fine white punchbowls and they hope they will drink out of them and they all shake hands and settle the matter, and Griffiths leaves, crossing the Chattooga River and it is a terrible journey, very rotten and dangerous roads, and he is ‘a littler in Fear of every Leaf that rattled’. And he is ambushed by a storm, eighteen hours of sleet until there is ‘scarce life in either me or my poar horse’ and he reaches an Indian hut, ‘when I advanced near the fire, it overcame me and I fell down’. The squaw wraps him in a bearskin and blanket, and feeds him and his horse.

November. On the 3rd, he gets to the Ayoree Mountain:

Here we laboured hard for 3 days in clearing the Rubbish out of the old pit, which could not be less than twelve or fifteen ton; but on the fourth day, when my pitt was well clean’d out, and the Clay appear’d fine, to my great surprise, the Chief men of Ayoree came and took me prisoner, telling me I was a Trespasser on their land, and that they had receiv’d private instructions from Fort George not to suffer their pitt to be opened on any account.

You are stopped again and this is very difficult, as there is now a price to be paid of 500 cwt of leather for every ton, a huge price.

Griffiths writes again, ‘this proves of very ill consequence to me, as it made the Indians set a high value on their white Earth’, and there are four hours of strong talk before they shake hands.

In Four days from this I had a ton of fine clay Ready for the packhorses, when very impertinently the weather changed and such heavy rains fell in the night, that a perfect Torrent came from the upper mountains with such rapidity, that not only fill’d my pitt, but melted, stained and spoil’d near all I save and even beat thr’o our wigwam and put out our fire, so that we were nearly perish’d with wet and cold.

The rain also washes the stratum of red clay into the pit and stains and spoils a ‘vast deal of white clay’.

This is a severe winter. Apart from the rains, it is bitter and the Tennessee River freezes over and the pot is ‘ready to freeze on a slow fire’. There are now regular and troublesome visits from the Indians, but Griffiths gives them rum and music and they part well, if carefully; ‘they hoped I should want but a few horse loads of white clay and pray’d I would not forget the promise I made ’em, but perform it as soon as possible’.

He will come back with porcelain made from their earth.

It is 20 December 1767. In pelting rain, high in the mountains of the Cherokee Nation, an Englishman is making safe five tons of white earth, packing it into casks, battening, preparing a train of pack animals.

On the same day in Plymouth, William writes to Pitt. ‘You said we were in sight of land. I am vastly mistaken if we are not now Entering our port.’

Here too, it is a day of Greater Rain.

ii

The packhorses are loaded with white earth and on 23 December Griffiths takes his leave of this cold and mountainous country with the frosty weather breaking, and ‘the mountain paths being very narrow and slippery we killed and spoiled some of the best horses and at last my own slipt down and rolled several times over me; but I saved my Self by laying hold of a young Tree, and the poar Beast Tumbled into a creek and was Spoiled’.

‘I had’, Griffiths writes, ‘Severall hundred Miles to Travill, besides the loss of a fine Young Cherokee horse.’

Griffiths loads five wagons with five tons of clay to take down through the backcountry to Charleston, where he pays for porters and rum for the wagoners and for coopers and two casks and buys sundry sea stores and ‘On the first of March I agreed for freight and passage with Capt. Morgan Griffiths of the Rioloto, bound for London’, £73 and ten shillings with £70 for the freight of the clay. And Thomas Griffiths bids farewell to Charleston and sets sail.

There is an unmerciful sea. ‘On the fourteenth Aprill we arrived in the Downs and on the Sixteenth, Capt. Griffiths, Mr John Smith, and my Self Left the Ship in the pilots charge at Graves End, and came to London, by Land.’

Thomas Griffiths pays £3 and ten shillings to bring ‘things on shore and attending the Clay when the Ship lay in the River’ and delivers Josiah Wedgwood his white earth, the unaker of the Cherokee, from the other side of the world.

As promised.