Thoughts Concerning Emigration

i

Champion is in trouble.

He has his warehouse at No. 17 Salisbury Court, Fleet Street, for the sale of his porcelain, but sales are poor. On 2 March 1776, he advertises again in the Bristol Journal and plays the nationalism card, ‘Established by Act of Parliament. The Bristol China Manufactory in Castle Green. This China is greatly superior to every other English Manufactory. Its texture is fine, its strength so great that water may be boiled in it. It is a true Porcelain composed of a native clay.’

And the Bristol China Manufactory stumbles to an end. Like Plymouth.

There are all kinds of endings, all of them untidy, and this one shares the tumbleweed feeling of energy trickling away, debt, grand possibilities diminishing month by month. This was to be the new Dresden, but the plates keep warping. Your English Arcanum, the delicate balancing of growan clay and growan stone, has been printed in the Monthly Register. Anyone can have a go. Wedgwood is back in Etruria with God knows what contracts signed, deals achieved. But bankruptcy looms here in Bristol.

Champion owes a huge amount of money and to some serious men of business. I find an inventory for the sale of another bankrupt pottery in Bristol around this time and realise the problem. The whole quantity of 324 pot boards, three benches, one pounding trough and one mixing trough, a clay chest, three complete wheels and wheel frames, working benches, moulds and drums, a kiln ladder, salting boxes, lignum vitae blocks and a hand mill, are valued at only £10. The ‘Old iron pot in the Yard’ is four shillings and sixpence.

His assets are negligible, a word that crumbles scant as rust.

The premises are sold off to a pipe maker. The investors cannot be paid back fully, and Champion is brought before Meeting in Bristol to explain himself to the Friends. He is unable to. The remaining stock is auctioned, the men dispersed.

ii

The only thing of any value is the patent. Champion goes to Etruria in the hope of selling it on.

The Josiah Wedgwood Works take up six acres alongside the new canal for bringing the clay and coal in and transporting out the jasperware, figures, Queen’s Ware. Four hundred people are employed here. It is a place of careful disposition of time and Wedgwood is counting.

Amongst other things, Mr Champion of Bristol has taken me up near two days. He is come amongst us to dispose of his secret, his Patent etc. Who would have believed of it – he has chosen me for his friend and confidant! I shall not deceive him, for I really feel much for his situation – a wife and eight children, to say nothing of himself to provide for, and out of what I fear will not be thought of much value here, the secret of china making. He tells me he has sunk £15,000 in this gulf and his idea now is to sell the whole art, mistery and patent for £6,000.

And, he adds, it is ‘one of the worst processes for china making’.

Wedgwood knows this, as he has been experimenting: ‘You can hardly conceive the trouble these white compositions give me … I am very sensitive of their variations, but find it almost impossible to avoid them.’ He gives Champion a list of other potters to try.

On 24 August 1778, Wedgwood writes to Bentley: ‘Poor Champion, you may have heard, is quite demolished. It was never likely to be otherwise, as he had neither professional knowledge, sufficient capital. Nor scarcely any real acquaintance with the material he was working upon.’

He adds, casually, ‘I suppose we might buy some Growan stone and Growan clay now upon easy terms, for they prepared a large quantity this last year.’

iii

Champion is on his knees. He publishes An Address by Richard Champion to the Pottery to garner support. There are, remarkably, enough takers for a new factory, the New Hall China Manufactory, to start under the guidance of men with professional knowledge. Champion can walk away.

And in a moment of brief, tremulous balancing of political power, friendship and patronage, he becomes joint Deputy Paymaster General under Burke with a stipend of £500 per annum and a suite of rooms in Chelsea, substantial enough for the children. He makes a misjudgement about money with a clerk, which is noted and which embarrasses his patron, reflects badly on his abilities, if not his probity. Months later the government changes. Champion has even less to tether him.

In 1783, Wedgwood publishes and distributes gratis, An Address to the Workmen in the Pottery, on the subject of entering into the Service of Foreign Manufacturers. It deals with ‘the dangerous spirit of emigration’.

In 1784, Champion emigrates with his wife Judith and seven children. They are on board the Britannia, on 20 October, as they pass the Lizard, the last of England, rich with soapstone, riddled and hollowed by mines for the porcelain trade.

The last sight of the British shore sunk deep into my heart, and left an impression which will not be easily erased. The evening we parted from it was serene and the sun dipped his beams to the Westward in a calm and unruffled ocean. The Lizard Point was in view … the gathering distant clouds, seemed to tell us, that it was time to leave infatuated Britain.

He writes and writes in his journal, and by the time they land in America it has become a hundred pages of a pamphlet: Thoughts Concerning Emigration.

iv

They are going to South Carolina, to live in Rocky Branch, a tributary of Granny’s Quarter Creek. This is ten miles north of Camden, 130 miles from Charleston, ‘where the heat is less intense’, and where the provisions are cheap and there are ‘no musctoes’. ‘I came to America in search of the Virtues of Simplicity, so becoming in a new Republic’, he writes to a friend.

There are no more letters from Burke, who has crossed over from one party to the other; he is ‘spared the pain of correspondence’.

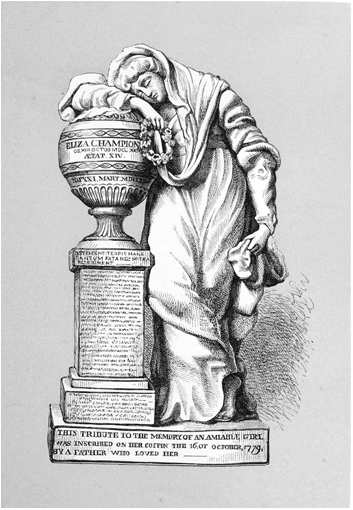

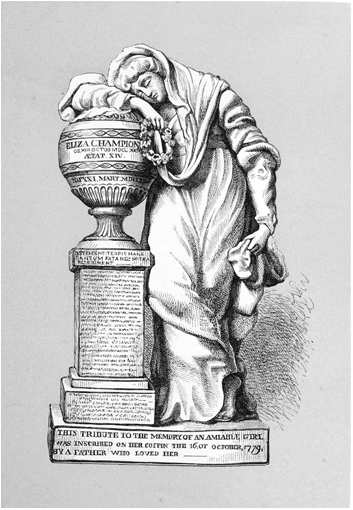

The family bring some things with them. Most precious is a memorial, thirteen inches high in unglazed porcelain, a figure of a weeping woman leaning on an urn supported by a pedestal. She is clutching a wreath and her eyes are closed and every part of her is heavy.

It is very white.

The urn simply says Eliza Champion and has her dates. She was fourteen. Champion has spent time on this memorial, writing a long, sad Latin inscription from Virgil on the cornice of the pedestal.

Engraving of Champion’s memorial to his Eliza, 1779

And then because he cannot stop, the whole of the plinth is covered in his writing, small and careful and urgent, necessary:

We loved you my dear ELIZA, whilst you were with us. We lament you now you are departed. The Almighty God is just and merciful, and we must submit to his will, with the Resignation and Reverence becoming human frailty. He has removed you Eliza from the trouble which has been our lot, and does not suffer you to behold the scenes of horror and distress in which these devoted Kingdoms must be involved. It is difficult to part with our beloved Child, though but for a season … Happy in each other, we are happy in you Eliza, and will with contented minds cherish your memory till that period arrives when we shall all meet again, and pain and Sorrow shall be thought of no more. R.C. J.C.

And on the pedestal ‘This tribute to the memory of an amiable girl was inscribed on her coffin the 16th October 1779, by a father who loved her.’

He has finally made something real and true out of porcelain.

v

Wedgwood has been painted by Stubbs, is a fellow of the Royal Society, a member of the Lunar Society. Alongside teacups he makes fossil cups for mineralogical specimens, measuring cups for use by chemists, druggists and apothecaries, mortars that ‘will be of great Use to Chymists, Experimental Philosophers and Apothecaries’. He writes to James Watt, the mechanical engineer and developer of the steam engine, that ‘I never charge such experiment pieces to anybody, & it would be unreasonable in you to expect in this instance to be favor’d beyond the rest of mankind.’

Wedgwood is using a good French white clay, finer than the American. He has tested the clay from Sydney Cove, brought back by Captain Cook, found it wanting. The Green Frog Service, 957 pieces strong with all the principal views of the whole of the United Kingdom, has been delivered and is in use by Catherine, empress of all the Russias, in her palaces in St Petersburg. Several of the views show the picturesque sights of Cornwall, its moors and rocky coastline.

He writes to his friend Dr Erasmus Darwin, who is writing a long poem, The Botanic Garden, in which the whole of creation is explored in Swedenborgian rhythms. Darwin has got to Clay and Wedgwood wants the Chinese to have their fair share of the acclaim: ‘I am a little anxious that my distant brethren may have justice done to their exertions in the plastic art.’ He tells Darwin to read the letters of Père d’Entrecolles on ‘Ka-o-lins and Pe-tun-tses’.

Wedgwood is a great man. ‘I hope white hands will continue in fashion’, he writes to Bentley, thinking of how his new wares look as they are picked up.

And in Etruria, in his new and beautiful redbrick house overlooking the new canal, Wedgwood muses to his business partner Bentley on the value of white earth:

I have often thought of mentioning to you that it may not be a bad idea to give out, that our jaspers are made of the Cherokee clay which I sent an agent into that country on purpose to procure for me, & when the present parcel is out we have no hopes of obtaining more, as it was the utmost difficulty the natives were prevail’d upon to part with what we now have … His Majesty should see some of these large fine tablets, & be told this story (which is a true one for I am not Joking) … as has repeatedly enquir’d what I have done with the Cherokee clay. They want nothing but age & scarcity to make them worth any price you could ask for them.

It is the story of scarcity that matters. ‘A portion of Cherokee clay is really used in all the jaspers so make what use you please of the fact’, he writes, cannily.

All the famous jasperware, the hard blue neoclassical cameos and vases and garnitures in their Horatian self-confidence, one enunciated, grammatically correct vessel after another hold a part of unaker, of a promise made, hands shaken.

The world and its geology are in obeisance.