i

I’m in China. I’m trying to cross a road in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province, the city of porcelain, the fabled Ur where it all starts; kiln chimneys burning all night, the city ‘like one furnace with many vent holes of flame’, factories for the imperial household, the place in the fold of the mountains where my compass points. This is the place where emperors sent emissaries with orders for impossibly deep porcelain basins for carp for a palace, stem cups for rituals, tens of thousands of bowls for their households. It is the place of merchants with orders for platters for feasts for Timurind princes, for dishes for ablutions for sheikhs, for dinner services for queens. It is the city of secrets, a millennium of skills, fifty generations of digging and cleaning and mixing white earth, making and knowing porcelain, full of workshops, potters, glazers and decorators, merchants, hustlers and spies.

It is eleven at night and humid and the city is neon and traffic like Manhattan and a light summer rain is falling and I’m not completely sure which way my lodgings are.

I’ve written them down as Next to Porcelain Factory #2 and I thought I could pronounce this in Mandarin, but I’m met with busy incomprehension, and a man is trying to sell me turtles, jaws bound in twine. I don’t want his turtles, but he knows I do.

It feels absurd to be this far from home. There is televised mah-jong at high volume in the parlours with their glitter balls like a 1970s disco. The noodle shops are still full. A child is crying, holding her father’s finger as they walk along. Everyone has an umbrella but me. A barrow of porcelain models of cats is wheeled past under a plastic tarp, scooters weaving round it. Ridiculously someone is playing Tosca very loudly. I know one person in the whole city.

I haven’t got a map. I do have my stapled photocopy of the letters of Père d’Entrecolles, a French Jesuit priest who lived here 300 years ago and who wrote vivid descriptions of how porcelain was made. I’ve brought them because I thought he could be my guide. At this moment this seems a slightly affected move, and not clever at all.

Pages from Père d’Entrecolles’ letters on Chinese porcelain, 1722

I’m sure I’m going to die crossing this road.

But I know why I’m here, so that even if I’m not sure which way to go, I’ll go confidently. It is really quite simple, a pilgrimage of sorts – a chance to walk up the mountain where the white earth comes from. In a few years I am turning fifty. I’ve been making white pots for a good forty years, porcelain for twenty-five. I have a plan to get to three places where porcelain was invented, or reinvented, three white hills in China and Germany and England. Each of them matters to me. I have known of them for decades from pots and books and stories but I have never visited. I need to get to these places, need to see how porcelain looks under different skies, how white changes with the weather. Other things in the world are white but, for me, porcelain comes first.

This journey is a paying of dues to those that have gone before.

ii

A paying of dues sounds appallingly pious but it isn’t.

It is a lived truth, a bit declamatory, but a truth none the less. If you make things out of porcelain clay, you exist in the present moment. My porcelain comes from Limoges in the Limousin region of France, halfway down on the West. It comes in twenty-kilo plastic bags, each bag with two ten-kilo sausages of perfectly blended porcelain clay, the colour of full-fat milk, with a bloom of green mould. I unwrap one and thump it down on to my wedging bench, pull the twisted wire through a third of the way along, pick up the lump and push it into the bench, raising it and pushing it down in a circular motion, like kneading dough. It gets softer as I do this. I slow down and the clay becomes a sphere.

My wheel is American and silent and low to the ground, jammed up against the wall in the middle of the slightly chaotic studio. I look at the white brick wall. There are too many people in this small space, two full-time and two part-time assistants to help with glazing and firing and logistics and the deluge of mail from my last book. There is too much noise from the neighbours. I need another studio. Things are going well. I have just been invited to show in New York and I have a dream of walking through an expansive gallery, full of light, walking far away from a piece of my work, turning around and seeing it with new eyes, alone, seeing it as if for the first time. Here I stretch my long arms and touch packing crates. I can get fifteen feet away. On a good day.

Everyone is being as quiet as they can but, damn it, the concrete floor is noisy. There is an argument outside. I need to make time to be nice to estate agents again as getting a studio is difficult in London. All those useful bits of space where people used to make things or mend them round the backs of house are being developed for apartments. I need to talk to the accountant.

I sit at my wheel.

And I throw the ball of clay into the centre, wet my hands and I am making a jar now and pulling the clay up with the knuckle of my right hand on the outside, three fingers of my left tensed inside to support, as the walls grow taller and the volume changes like an exhalation, something being said. I’m in this moment while also being elsewhere. Altogether elsewhere. Because the clay is the present tense and a historical present. I’m here in Tulse Hill, just off the South Circular road in South London, in my studio behind a row of chicken takeaways and a betting shop, sandwiched between some upholsterers and a kitchen-joinery workshop, and as I make this jar I’m in China. Porcelain is China. Porcelain is the journey to China.

It is the same when picking up this Chinese porcelain bowl from the twelfth century. The bowl was made in Jingdezhen, thrown then moulded with a flower in a deep well, unglazed rim, green-grey with a slightly pooled glaze, some issues as the dealers would say, chips, marks, scuffs. It happens in the present tense and it is, itself, a continuous present of active, dynamic movements, judgements and decisions. It doesn’t feel in the past, and it feels wrong to force it into one just to obey a critical orthodoxy. This bowl was made by someone I didn’t know, in conditions that I can only imagine, for functions that I may have got wrong.

But the act of reimagining it by picking it up is an act of remaking.

This can happen because porcelain is so plastic. Pinch a walnut-sized piece between thumb and forefingers until it is as thin as paper, until the whorls of your fingers emerge. Keep pinching. It feels endless. You feel it will get thinner and thinner until it is as thin as gold leaf and lifts into the air. And it feels clean. Your hands feel cleaner after you have used it. It feels white. By which I mean it is full of anticipation, of possibility. It is a material that records every movement of thinking, every change of thought.

What defines you?

You are by the sea at the turn of the tide. The sand is washed clean. You make the first mark in the white sand, that first contact of foot on the crust of sand, not knowing how deep and how definite your step will be. You hesitate over the white paper like Bellini’s scribe with his brush. Eighty hairs from the tail of an otter ends in a breath, a single hair steady in the still air. You are ready to start. The hesitation of a kiss on the nape of the neck like a lover.

I pull the twisted metal wire under my finished jar, dry my fingers on my apron and pick it up from the wheel, place it with brief satisfaction on a board to my right. Reach for another ball of clay and begin again.

It is white, returning to white.

iii

This moment, this pause, holds a kind of grandeur.

Porcelain has been made for 1,000 years, traded for 1,000 years. And it has been in Europe for 800 of these. You can trace a few shards earlier. These broken fragments of Chinese pot gleam provocatively alongside the heavy earthenware pitchers they were found with and no one can work out how they got to this Kentish cemetery, this Urbino hillside. There are scatterings of porcelain across medieval Europe in inventories of Jean, duc de Berry, a couple of popes, the will of Piero de’ Medici with his una coppa di porcellana, a cup of porcelain.

You see a glimpse of white in a list of presents given on an embassy from one princeling to another: a stallion, a jar of porcelain, a tapestry with golden thread. It is so precious, goes the story in medieval Florence, that a porcelain cup prevents poison from working. A beautiful celadon-green bowl is deeply encased in silver and disappears into a chalice. A wine jar is mounted and becomes a ewer for a banquet. You can even see a glimpse in a Florentine altarpiece; one of the kings kneeling stiffly before the Christ child seems to be offering him myrrh in a Chinese porcelain jar, and this homage seems about right for a substance so scant and so arcane, for an object that has come such a long way from the East.

Porcelain is a synonym for far away. Marco Polo came back from Cathay in 1291 with his silks and brocades, the dried head and feet of a musk deer and his stories, a Divisament dou monde, his Description of the World.

The stories of Marco Polo are iridescent. Every element glistens and glitters as strangely as lapis lazuli, throwing off shadows and reflections. They are digressive, repetitive, rushed, rehearsed. ‘In this city Kublai Khan built a huge palace of marble and other ornamental stones. Its halls and chambers are all gilded, and the whole building is marvellously embellished and richly adorned.’ Everything is different, marvellously, richly so. Tents are lined with ermine and sable.

Numbers in Marco Polo are either vast – 5,000 gerfalcons, 2,000 mastiffs, 5,000 astrologers and soothsayers in the city of Khan-balik. Or singular. A great lion that prostrates himself with every appearance of great humility before the khan. A huge pear that weighs ten pounds.

And colours are drama. Palaces are decorated with dragons and birds and horsemen and various breeds of beasts and scenes of battle. The roof is all ablaze with scarlet and green and blue and yellow and all the colours that are so brilliantly varnished. There is a feast, recounts Marco Polo breathlessly, for the New Year in February:

and this is how it is observed by the Great Khan and all his subjects. According to custom they all array themselves in white, both male and female, as far as their means allow. And this they do because they regard white costumes as auspicious and benign, and they don it at the New Year so that throughout the year they may enjoy prosperity and happiness. On this day all the rulers, and all the provinces and regions and realms where men hold land or lordship under his sway, bring him costly gifts of gold and silver and pearls and precious stones and abundance of fine white cloth … The barons and knights and all the people make gifts to one another of white things … I can assure you for a fact that on this day the Great Khan receives gifts of more than 100,000 white horses.

Marco Polo reaches ‘a city called Tinju’. Here,

they make bowls of porcelain, large and small, of incomparable beauty. They are made nowhere else except in this city, and from here they are exported all over the world. In the city itself they are so plentiful and cheap that for a Venetian groat you might buy three bowls of such beauty that nothing lovelier could be imagined. These dishes are made of a crumbly earth or clay which is dug as though from a mine and stacked in huge mounds and then left for thirty or forty years exposed to wind, rain, and sun. By this time the earth is so refined that dishes made of it are of an azure tint with a very brilliant sheen. You must understand that when a man makes a mound of this earth he does so for his children; the time of maturing is so long that he cannot hope to draw any profit from it himself or to put it to use, but the son who succeeds him will repay the fruit.

This is the first mention of porcelain in the West.

It describes porcelain as a material that is beautiful beyond comparison, that is complex to create, that these vessels are innumerable. Porcelain demands attention and dedication. And Marco Polo shrugs, ‘What need to make a long story out of it?’

And ‘Let us now change the subject.’

He came back with a small grey-green jar made from this hard, clear white clay unlike anything seen before. And it is in Venice that object and name come together and start this long history of desire for porcelain. The name of this grandest of commodities, this white gold, the cause of the bankruptcy of princes, of Porzellankrankheit – porcelain sickness – comes from eye-stretching Venetian slang, the vulgar wolf-whistle after a pretty girl. Porcellani, or little pigs, is the nickname for cowrie shells, which feel as smooth as porcelain. Cowrie shells lead, obviously, to Venetian lads, to a vulva. Hence the echoing shout.

iv

Marco Polo can change the subject but I can’t. Knowing that this jar is somewhere in the Basilica di San Marco in Venice, it is imperative that I go and find it.

I start out straightforwardly: ‘I’m an English writer and potter and I’m trying to find…’, but letters and emails disappear into nothing. I escalate. ‘The papal nuncio recommended that I contact you…’ Still nothing. A phone rings on a mahogany desk. Perpetual lunch, I assume sourly. Or, a second bottle of wine, or a holiday celebrating some Republican martyr.

I borrow Matthew, my middle child, and decide to chance it.

We get to the far left corner of the basilica, the knots and eddies of tourists, handbag salesmen scanning for police, and through the glass doors of the patriarchate where I make my pitch to a monsignor who is charmed and delighted and suggests tonight, when everything is closed? There are, he stretches and sighs, in a pantomime of weariness, far far too many foreigners in the basilica in the day.

Always take a child, if possible, to Italy.

And as they are closing up we are taken by the man with the key along a marble corridor in the patriarchate past endless portraits of cardinals and into the shadows, the rolling swell of the marble pavements of the basilica with its dull glimmerings, the red flare of the sanctuary lamps, into the treasury.

It is small and high-vaulted. Rock crystal and chalcedony, agates, an Egyptian porphyry urn, a Persian turquoise bowl held in a golden vice; all materials that hold light. Chalices. A reliquary of the True Cross with gems set emphatically as a child’s kisses. This is Byzantium, this treasury, Christ ascendant, conquering, one object after another from somewhere far away transfigured through Venetian skill.

And my jar is there, at the back of a cabinet between a pair of incense holders and a mosaic icon of Christ. It is five inches tall, I guess, far less than a hand span, a frieze of foliage, four small loops below the neck to hold a lid, five indentations for thumb and fingers. An object for a hand’s memory. I can’t pick it up. The clay looks grey and rough and a bit raggedy where it has been trimmed roughly. It has come a very, very long way.

We peer it at it for ten minutes until the man with the key starts tapping his foot. The treasury is locked up. The basilica is empty.

It is a start. Matthew is pleased I’m pleased and we go and celebrate at Florians in the piazza with hot chocolate and macaroons.

v

Any obsession with porcelain echoes as much as any Venetian alleyway.

What is it? It is ‘made of a certain juice which coalesces underground and is brought from the East’, wrote an Italian astrologer in the mid-sixteenth century. Another writer asserted that ‘eggshells and the shells of umbilical fish are pounded into dust which is then mingled with water and shaped into vases. These are then hidden underground. A hundred years later they are dug up, being considered finished, are put up for sale.’

There is agreement on the strangeness of porcelain, that it is subject to alchemical change, rebirth. John Donne movingly writes in his ‘Elegy on the Lady Markham’, of her transformation in the earth, that when you lose something precious to sight, something rarer and more beautiful can be created: ‘As men of China, after an age’s stay, / Do take up porcelain, where they buried clay’.

So how do you make it? How do you make it before anyone else makes it? How can you have a single piece? How can you have it all, surround yourself with it? Can you ever get to the place it comes from, the source of this river of white?

Porcelain is the Arcanum. It is a mystery. For 500 years no one in the West knew how porcelain is made. The word Arcanum, a jumble of Latin consonants, is pleasingly close to Arcady, Arcadia. There must be some kinship, I feel, between the first secret of white porcelain, and the promise of fulfilled desire, a kind of Arcadia.

vi

White is also my story. From my very first pot.

I was five. My father went on Thursdays to an evening class at the local art college to make pots, taking my two older brothers with him. You could do screen printing on to T-shirts or paint scumbly canvases. You could go up to life drawing, a lady in front of a draped red velvet curtain with a plant in a brass container, or you could go down to the basement and make pots. And I wanted to go down the stairs. There was a break after an hour and you were allowed a glass of Ribena and a chocolate biscuit.

It was dusty. Dust settles around clay. Someone was pinching a very small bowl out of white clay, cradling it in her hand and turning it round rhythmically.

I sat at the electric wheel with a large ball of brown clay. I wore a red plastic apron. The wheel was very big. It had an on and off switch and a foot pedal for speed that you depressed and was hard to push.

And next week my pot is there, hard and grey and dulled, smaller. You can dip it, says my teacher, into one of a dozen glaze buckets to make it sing in different colours and you can paint on to it in every colour. What are you going to decorate it with? She smiles. What does this pot need? I push my pot into the white glaze, as thick as batter.

And the following week I take home my white bowl, three waves of clay as fat as fingers, a scooped inside with a whorl of marks and heavy, but a bowl and white and mine: my attempt to bring something into focus. The first pot of tens of thousands of pots, forty-plus years of sitting, slightly hunched with a moving wheel and a moving piece of clay trying to still a small part of the world, make an inside space.

I was seventeen when I touched porcelain clay for the first time. All through my schoolboy years I had made pots every afternoon with a potter whose workshop was part of the school. Geoffrey was in his sixties, had fought in the war, was damaged by his past. He smoked untipped Capstan cigarettes, quoted Auden poems. His tea was deep brown like the clay we used. He made pots for use. They had to be cheap enough to drop, he’d say, beautiful enough to keep for ever. I’d left school early to start a two-year apprenticeship with him, and I spent a summer in Japan with different potters, trailing around the famous kilns where folk craft wares were made, the traditional villages where wood-fired tea bowls and jars were still being made. These pots were what I aspired to make – alive to texture and chance, good in the hands, robust and focussed on use. And on one humid afternoon in Arita, a porcelain town far down at the end of Japan, I sat and watched a National Living Treasure paint a few square centimetres of a vase with a brocade pattern in red and gold. It looked tight, breathless with expensive exactitude.

His studio was silent. His apprentice was silent. His wife opened the paper screen with a sound like a sigh, bringing tea in porcelain cups and white bean-curd cakes.

But I was given a small piece of the clay and worked it in my hand until all the moisture had gone and it crumbled.

vii

I am a potter, I say, when asked what I do. I write books, too, but it is porcelain – white bowls – that I claim as my own when challenged by the dramatic Syrian poet sitting on my right at a lunch.

Do you know, she says straight back, that when I got married in Damascus in the early 1970s, I was given a porcelain dish this big – she sweeps her hands wide – that my mother had been given by her mother. Pink porcelain. And I was given a pair of gazelles. They tucked their legs up under them on the sofas like hunting dogs. We all love porcelain in Damascus. The politician’s wife on my left wants to cut in on Damascus – there is depressing news – but I need to know more about this pinkness. I’ve never heard about pink porcelain, it sounds unlikely.

But the marriage gift bit sounds right, ceremonial, particular, freighted. Porcelain has always been given away. Or stored and then brought out on special occasions to be handled with that slight tremble of care that hovers around anxiety.

And Damascus is intriguing as it is on the way from Yemen to Istanbul, or could be on the way if you wanted it to be and I remember, somehow, that a Yemeni sheikh collected Chinese porcelain in the twelfth century. The greatest collection ever, brought together to celebrate the circumcision of his son. There are supposed to be porcelain shards in the dunes near Sana’a. We talk about how to get to Yemen, about her grandmother’s porcelain dishes and where they came from. We are still talking porcelain as the plates are cleared.

When I come back to the studio from this lunch I write up the conversation. And I put down another place, Damascus, on my list of places I have to visit. I have my three white hills in China, Germany and England and when I can’t sleep I run through my list trying to make patterns out of the names, shifting them into clusters of places where white earth was found, where porcelain was made or reinvented, where the great collections were made or lost, where the ships dock and unload, the caravanserai stop. I connect Jingdezhen with Dublin, St Petersburg with Carolina, Plymouth and the forests of Saxony.

Go from the purest white in Dresden to the creamiest white in Stoke-on-Trent. Follow a line. Follow an idea. Follow a story. Follow a rhythm: there are meant to be unopened cases of imperial porcelain in a Shanghai museum, left on the quayside when Chiang Kai-shek sailed for Taiwan in 1947. And cases of Chinese porcelain still packed up after 500 years in a cellar of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. I could go there and work my way across to Iznik where they made white pots in imitation of unattainable porcelains, delicate jars with tulips, carnations and roses bending slightly in a breeze.

I’m making small porcelain dishes today, a few inches across, to stack together in rhythmical groups. I could follow this simple image of repetition. There was a monastery in Tibet, travelling with my girlfriend Sue over twenty-five years ago, before we married, where there were stacks of Sung Dynasty porcelain bowls low down behind chicken wire in cupboards in a long hall. I can remember the sounds – a dog, laughter – and I can see the coils of incense rising into the impossible clarity of the air. I can remember the massed porcelain, the feeling of casual, untidy plenitude.

Or it could be a journey through singular, spectacular beauty. There is meant to be another piece of Marco Polo’s porcelain in Venice in some ducal palazzo somewhere, if I can face it.

Or I could journey through shards.

Porcelain warrants a journey, I think. An Arab traveller who was in China in the ninth century wrote that ‘There is in China a very fine clay with which they make vases which are as transparent as glass; water is seen through them. These vases are made of clay.’ It is light when most things are heavy. It rings clear when you tap it. You can see the sunlight shine through. It is in the category of materials that turn objects into something else. It is alchemy.

Porcelain starts elsewhere, takes you elsewhere. Who could not be obsessed?

viii

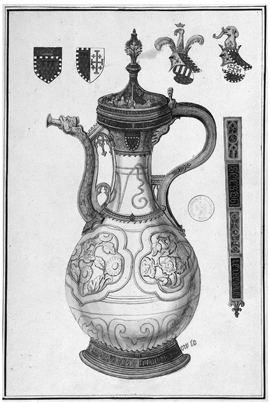

Obsession builds. As I’m starting a journey, these first porcelains to arrive in Europe from China hold a claim on me. They are beginnings, after all. I return from Venice and Marco Polo and I realise that I need to see the Fonthill vase. It is the most irreproachably aristocratic, double-barrelled porcelain object in Europe: its proper name is the Gaignières-Fonthill vase.

Watercolour of the Gaignières-Fonthill vase, 1713

If you want provenance it is here: a Chinese vase from the early fourteenth century augmented with medieval silver heraldic mounts that has been in the collections of Louis the Great of Hungary, the king of Naples, the duc de Berry, then the dauphin of France in his rooms at Versailles, and then a great antiquarian collector until the French Revolution, when it was bought by the English author and collector William Beckford, who kept it in his strange cabinets of curiosities in his ersatz Gothic palace at Fonthill. And then his finances collapsed and it was sold, sold again and disappeared from view.

It is now in a Dublin barracks, an acre of grey tarmac and grey stone walls like cliffs. This is where the British garrisoned for a hundred years, drilling regiments, thousands of stamping feet echoing off the sheer faces of the building. It is now the National Museum of Ireland, Decorative Arts and History.

I go in November and the museum is spectacularly empty. I’m taken up to the office of the Keeper of Decorative Arts – proper piles of books on the floor – where it is lying in bubble wrap in an orange crate. We put on white gloves and the vase is lifted out.

It is a flummery of ideas. It is decorated with flowers and foliage under a pale grey-green glaze, and your eye might travel across it as you see Old and Chinese and Jar. It is all those, but it is also New, a trying-out, a conversation in a workshop, an attempt to create an extra depth to a porcelain vessel.

And it’s a complicated new shape, too. To handle it, scrape a layer away – a few millimetres – to make a slight recess, damp the clay, and then press with affection the sprays of leaves and the daisies, and clean up the small scrapings and indentations, without knocking it, without it all collapsing, folding into your hands, is very hard.

I hold it. And it becomes clear that the trails of minute porcelain balls that sway and swag their way round the vase are just wrong. They were meant to add texture to the proportions, clarify and define the transition between neck and shoulder, but they do that bad fashion shtick of calling attention to an unexpected part, so that this fulsome curve is more of a bulge. And one trail has given up and slipped like a hem, untucked. And it has been lifted too warm from the saggar – the container of rough clay that protects porcelain from the smoke and flames of the kiln during the firing – as the kiln was unpacked and so the base has cracked. There are many complexities to working with porcelain. Any discrepancy in thickness can lead to fractures, as it cools from 1,300 degrees Celsius – the white heat of the firing – down to 300 degrees, when it’s safe to handle. You can get away with unevenness with other kinds of clay, but it is chancy with porcelain. Your errors, your slapdash decisions, are revealed.

Where you run your finger over the foot ring, the thickness of this vase is astray. But for whoever made this it was good enough.

I love these moments when you feel the decision. This was to smudge a piece of wet clay over an incipient crack and press down and move on. Good enough is not a term in art history, I think, as I slowly shift the vase round in my hands from daisies to camellias to daisies, but Good enough should be there. I hold the Gaignières-Fonthill vase and think of the Silk Road from China and the kingdom of Naples and the duc de Berry – the poor young dauphin trying to impress his unimpressible father – then Beckford collecting his treasures like a Medici in a damp valley in Wiltshire. The silver mounts have gone leaving very small drilled holes to show where they were attached 600 years ago.

I’ve taken off the Michael Jackson white gloves and sit with it in my hands. This is a moment of some danger. I could follow this, I think.

It is a lure.

Following this means a journey into connoisseurship, pedigree, a history of collections, and good God, I’m not doing that again. My last book followed an inherited collection of netsuke, small Japanese carvings, across five generations of my family: I know what collecting and inheritance entails. Before I came here to Dublin to pay homage I read the strange Gothic novel of Beckford and looked up in the sales catalogue to find where this beautiful thing stood amongst his treasures, and I can see how I could lose myself in his fantasy, mired in sultans and concubines and gerfalcons and all that sort of embroidered and gilded stuff. I can see unspooling time in archives, thinking about ownership. It would become a story of rich people and their porcelain.

This jar offers something different.

I’m late for the taxi to the airport, lunchless, high, and I run with the generous Keeper of Old and Strange Objects through the museum. She needs to show me a final thing before departure.

It is Buddha. He is reclining on an elbow, long fingers, bare feet, golden robes like eddies of water. Warm white marble. Stolen by Colonel Sir Charles Fitzgerald on a punitive military expedition to Burma and sent to join the Fonthill vase in 1891 to the museum in Dublin, where they sat near each other in Asia, Antiquities.

He is ‘taking it easy with hand under his cheek’ says Bloom in Ulysses. Molly recalls him breathing ‘with his hand on his nose like that Indian god he took me to show one wet Sunday in the museum in Kildare Street, all yellow in a pinafore, lying on his side on his hand with his ten toes sticking out’.

I count Buddha’s toes, then taxi, airport, home, wondering if Bloom or Molly or Joyce noticed the white vase in the case opposite in the echoey, mahogany-cased, imperially pillaged museum in Kildare Street on a wet afternoon.

Who could not be obsessed by porcelain? I write in my notebook.

And then after this foolish rhetorical question I write: most people. And then I add James Joyce.

ix

It’s not that I like all porcelain.

If you look at the cases of eighteenth-century porcelain in any museum, a shelf of palely loitering Vincennes, two of Sèvres, a bit of Bow, they seem irredeemably precious. Not only can you not work out what most of this stuff was for – a trembleuse, a chocolatier, a girandole – but there is a mismatch between the amount of work that has gone into it and the result. The thimble-small cup and saucer with a view of Potsdam, courtiers, gilding, was pointless then and looks like they did it because they could.

And because they can, they do. Dinner services for kings and queens and princelings aren’t in themselves interesting. There is an awful lot of it out there and I don’t want to get lost in the scholarship around small kilns of the eighteenth century.

I have a bowl, eight-sided, lobed and pinched, ten inches across and four high, with a sort of raised basketwork pattern, and a flat gilded rim. It is from Meissen, around the 1780s and it sits primly on a high foot, as if expecting to be the centre of a table and hence the centre of attention. There are panels on the outside with pears, apples, plums and cherries, and on the inside is a bouquet of fruit, redcurrants and strawberries and gooseberries and half a pear.

It is valuable. Its insipidity is total.

I’m not sure if its horridness is that everything is just so plump and sweet and high-summerish. You can taste nothing, no bite, no acidity, just sugariness waiting for the phlump of Schlagsahne, that coating of cream. You can feel the boredom in the fruit painter; berry, berry, berry.

Actually as I force myself to look at it, it is precisely the coming together of late summer in the 1970s – holidays as a teenager, boredom, small cottage, brothers, endless plums, blackberries, compulsive rereadings of bad novels – that makes me realise this is passive-aggressive porcelain.

I feel certain this is a new category of porcelain. I start a list.

x

A good list helps. And proper note taking, too, with full citations of where I’ve found references or quotations, seen a piece of porcelain that offers a lead for the journey. I have learnt from the research for my last book and this time I know how to do it. I have none of that stupid knock-it-off-in-six months bravado. I will not digress. I will plan this pilgrimage.

Pilgrimage is a complex word for me. I grew up near cathedrals and my childhood was full of pilgrims. We lived in a deanery, a vast house next to a cathedral. It was a house built and rebuilt over 600 years with grand rooms with panelling and portraits of deans. I had a room on the top corridor alongside my three brothers. The house gave up here with a lumber room, No War but Class War on our bathroom door, a table-tennis table, steps up to another tower where we smoked with school friends, plotted our lives.

My parents were proud of their open door. The Pope came. Princess Diana came. People came for meals, for weeks, for months. One American monk stopped wandering for a summer and stayed as a hermit for several years, using a room at the top of the spiral staircase in the tower, cleaning the house in the early hours in exchange for bed and board, and praying in our oratory.

I think my childhood was quite odd, choppy with priests, Gestalt therapists, actors, potters, abbesses, writers, the lost, the homeless and family-hungry, God-damaged, pilgrims.

Pilgrims don’t know what to do when they finally reach the end. We were the end. They go on and on about their journey. They share. This is a risk I add to my list, another list.

I’ve read Moby-Dick. So I know the dangers of white. I think I know the dangers of an obsession with white, the pull towards something so pure, so total in its immersive possibility that you are transfigured, changed, feel you can start again.

And there is the issue of time. I have a family. I have a proper life making porcelain. The diary is already full, but I can always write at night.

I have my ground rules for this journey to my three white hills. All I have to do is find my lodgings next to Porcelain Factory #2. I dodge the scooters and taxis and set off towards the south.

I have to be up at six for my first hillside.