DEFINING THE S-CLASS

The Mercedes-Benz S-Class has been a massive worldwide success story, one that is the envy of other car manufacturers. The car is almost universally regarded as the pinnacle of automotive excellence – ‘the best car in the world’, despite Rolls-Royce’s earlier use of that title – and has become a symbol of material success for its owners. It has become a benchmark of good taste in automotive design, and is seen also as a pioneer of new automotive technology of all kinds. Despite determined attempts by rival manufacturers to claim a share of the S-Class market, the car has retained its position at the pinnacle of luxury saloons for more than forty years.

That is a formidable achievement. Not content with building the most widely acknowledged automotive symbol of success, Mercedes has gone on to back it up with exclusive coupé derivatives, even more expensive and even more symbolic of material success. The sales of the S-Class have not only had a halo effect on the rest of the Mercedes marque, they have also enabled new technology to be introduced at the top end of the market while the car remains expensive – and have then managed to reduce its cost either by further development or simply by volume production, so enhancing the less expensive models in the company’s lineup as well. The business model is flawless, and those who have maintained it across five generations of the S-Class – with a sixth arriving as this book goes to press – deserve the praise that has been heaped upon them from enthusiasts and rivals alike.

This was how Mercedes saw the S-Class lineage in 1980. Far left is a ‘Fintail’ saloon; next is a W109; and then come the S-Classes proper – a green W116 and a yellow W126.

So how did the S-Class come about? When the first version, called W116 by its makers, reached the market in 1972, the Mercedes-Benz marque was making a new assault on international markets. Key among these was North America, where Mercedes models had been widely respected since the early 1950s, but where the company was still very much a bit-part player. New safety and emissions legislation introduced in the USA during the second half of the 1960s had caused enormous problems for domestic makers and importers alike, but Mercedes was determined to ‘hang on in there’. So although North American sales were not yet central to the Mercedes business plan, there was every intention of further exploiting what was then the world’s largest car market. US expectations were therefore as important in the thinking behind the original S-Class as were expectations in Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

This 1973 advertisement shows the first S-Class, the W116 (at the back of the group) in the context of its contemporaries. In the middle is the flagship SLC coupé, derived from the R107 SL roadster, and in front is the latest version of the W114 ‘stroke 8’ medium saloons introduced in 1968.

The long-wheelbase 300 SE of 1963 featured air springs, all-round disc brakes and an all-aluminium engine with fuel injection. Though essentially a top model for the ‘Fintail’ saloon range, it made clear that Mercedes was already thinking about building a better-equipped, luxury model with the latest technical innovations.

Most important, however, was that Mercedes had identified an enduring market for top-quality luxury cars, and intended to exploit it. Perhaps the first clear indication that such a market existed had been the success of the 220 SE coupé and cabriolet models introduced in 1961. In the Mercedes scheme of things, they replaced low-volume derivatives of earlier saloon ranges, but they grabbed the attention of a much wider audience. Mercedes would never admit publicly to being surprised by such a thing, but there can be little doubt that these cars helped the company to recognize that there was a readiness for the Mercedes marque among those prepared to spend more than most on their automotive transport.

Within four years Mercedes had a new model range ready to offer such customers. The range consisted entirely of saloons, which would necessarily be less expensive than the prestigious coupés and cabriolets, but which moved a step closer to them in their appeal and price. Like the coupés and cabriolets, they were actually derivatives of the then-current mid-size saloon platform, rebodied and re-engineered to suggest more prestige. They came with a choice of standard or long (limousine) wheelbases, and with either standard suspension as W108 types, or with advanced air suspension as W109s. They were a cautious first step in the direction of an autonomous ‘prestige’ saloon range, and during the mid-1960s Mercedes marketing linked them with the coupé and cabriolet models to reflect that more upmarket appeal.

Forerunner of the S-Class was the W108/W109 series, introduced in 1965. It shared much of its engineering with the earlier ‘Fintail’ saloons.

It worked extremely well. All these cars in fact had the letter S somewhere in their model designations, and this has led many writers to refer to them as the first S-Class. They were not, of course: that had yet to come. But they did show Mercedes the direction they needed to take when they came to create the first autonomous S-Class models during the later 1960s.

The Letter S

It is interesting to see where that letter S had come from and what meaning was invested in it. Before the 1939–45 war there had been several Mercedes models whose designations incorporated the letter S, but those had all been sporting models, and the S invariably stood for ‘Sport’. After the war, however, and before the Mercedes marque had re-established itself enough to risk entering the sports-car market, the letter S re-emerged with a different meaning: from 1951 it appeared on two new models derived from existing production ranges, and in each case it clearly stood for Special.

Those new models were the 170 S, a special cabriolet derivative of the core saloon range, and the 300 S, which was a coupé or cabriolet (and even roadster) derivative of the big 300 saloon range. When the Ponton saloons arrived in 1953 with a new 220 model, this was swiftly followed by a more powerful, better-equipped derivative that took the name of 220 S in 1954.

Sporting it was not, even though it did become a favourite as a long-distance rally car: the 220 S was all about adding a little more prestige at the top end of the Mercedes mainstream saloon range. It was not itself the most expensive saloon that Mercedes made, as the big 300 held that title. But the 300 was for the very wealthy, and for heads of state such as Germany’s own Konrad Adenauer, who used one so much that the car soon acquired the nickname of the Adenauer Mercedes. The 220 S was the saloon to which the man in the street could, and did, aspire.

When fuel injection reached the mainstream Mercedes range in 1958, the SE designation (Spezial Einspritzung, or Special Injection) took over at the top of the tree. And there it would remain for many years, although the letter S alone still had connotations of prestige. By this time, the suggestion of S for Special was gradually giving way to the idea of S meaning Sonderklasse, or Special Class, not least because the German maker DKW had actually called one of its cars exactly that – a DKW Sonderklasse. Mercedes did not demur, and this interpretation of the letter S would be the one that would be carried forwards into the 1960s.

The origins of the S-Class coupés certainly go back to those hugely successful coupés and cabriolets of the 1960s that had been based on the platform and running gear of the top-model saloons. Once the W108/W109 range had become available in 1965 and had begun to prove that there really were customers only too ready to pay for a more presti gious Mercedes-Benz saloon, the strategy must have become clear: in future there should be both an S-Class saloon range and related S-Class coupé models.

There never were any S-Class cabriolets, and that was probably the result of a historical accident. When the first-generation S-Class was being designed, motor manufacturers everywhere were convinced that the USA would sooner or later introduce new laws that forbade the sale of open cars on safety grounds. So no cabriolet was designed; and in fact, to save development time, no coupé derivative of the W116 S-Class was attempted, either. Instead, as Chapter 2 explains, a long-wheelbase coupé derivative of the SL roadster was developed in order to occupy the flagship coupé spot in the Mercedes range.

The C140 was in production for a relatively brief period, from 1992 to 1998. Though luxurious and technically advanced, it has always aroused mixed reactions.

The C126 was the first S-Class coupé, derived from the contemporary W126 saloon. It has become an enthusiasts’ favourite.

The threat to open cars had not receded by the time the second-generation S-Class cars were being developed, so again there was no open derivative on the agenda. There was a coupé derived directly from the saloon, however, and it set the pattern for those that would follow. Visually it was quite clearly related to the saloon, although it had its own distinctive styling cues and was based on a shortened platform. Mechanically it used only the engines from the top saloon models: so in this case there were only V8 engines with automatic gearboxes, and no 6-cylinder coupés with manual gearboxes. These first S-Class coupés, which are discussed in Chapter 4, were followed by coupé derivatives of the subsequent W140 saloon range.

The same principles lay behind the creation of the two subsequent flagship coupé ranges. These were the C215, derived from the W220 saloons, and the C216, derived from the W221 models. In every case the coupé models shared most of their equipment with the saloons, but where the saloons might be available with a feature only as an option, the coupés might have it as standard. Similarly, new features might be announced as innovations for the coupé models, even though in practice they became available on the saloons at exactly the same time. It all helped to suggest that the coupés were at the cutting edge of the Mercedes range and were therefore worth the substantial price premium that was being asked for them in the showrooms.

The C216 coupés were based on the W221 saloons and, as always, incorporated a mass of the latest technology.

The C215 was the coupé derivative of the W220 saloon, and had clear visual links to the contemporary SL sports models.

Since the late 1920s, Mercedes-Benz has given code numbers to its development projects, and from the beginning these numbers carried a W prefix. The W stands rather mundanely for ‘Wagen’, meaning ‘car’, and the number which follows it is probably best described as randomly selected. Although there seemed to be some sequence to the numbers in the very early days, when the W07 Grosser Mercedes was developed at around the same time as the W08 Nürburg model, things very soon departed from that simple system.

The first S-Class was developed with the model code of W116. It was replaced by a W126, although it appears that not all the numbers in between had been used up by other projects. The third-generation S-Class was called a W140, and then there was a big jump for the fourth generation to W220. Here, things seemed to settle for a while, as the W220 gave way to a W221, and the sixth-generation car was developed with the W222 code. Where the numbers may go after that is simply anybody’s guess.

The coupé derivatives started out by sharing the model codes of the saloons, although they took on project codes of their own from the mid-1990s. The W116 had no coupé equivalent, for reasons explained in Chapter 2. The coupé derivative of the W126 was known as a C126, that initial capital having been coined probably some time in the 1960s (at the same time, the R code was introduced for Roadster models of the SL class). The coupé derivative of the W140 was, logically, a C140 – but after that, things changed. Perhaps one reason was that the coupés required such major engineering programmes of their own that they needed separate project codes. So the coupé derivative of the W220 fourth-generation S-Class was a C215, and the coupé related to the fifth-generation W221 was a C216. However, there are indications that the coupé derivative of the W222 will revert to the original system and become a C222: time will tell.

The great original: this was the first-generation S-Class, the W116 model.

These project codes are found in the chassis numbers (VIN numbers) of the cars themselves, but they are not reflected in the names by which they are known to the public – those need their own explanation.

The suffix letters are the easiest to understand. So, in the beginning there were designations such as 280 S and 280 SE: the S simply indicated an S-Class car, in this case with a 2.8-litre carburettor-fed engine, while the SE indicated that the car had an engine of the same size but fitted with fuel injection (which delivered more power and better performance, but was also more expensive). On long-wheelbase derivatives, an L was added, so a typical designation might have been 280 SEL. On the coupés, a C was used, so that a typical designation would be 500 SEC.

But from June 1993, all that changed, because Mercedes entered a new era that would be characterized by a wider range of models, and it also changed the way it badged its cars. So the suffix letters became prefix letters, and what had once been a 500 SE now became an S 500; furthermore neither long-wheelbase nor coupé derivatives had any additional identifying letters, so the old 500 SEL and 500 SEC were also badged as S 500 types. It was all faintly unsatisfactory, and in fact from June 1996 the coupés were given their own identifying letters, becoming CL types. In common parlance, however, they were still S-Class coupés, and it seemed likely that the old S-Class designations might return with the coupés derived from the W222 models.

There were special letters for the diesel-engined models. When the first one arrived in 1978 it was a 300 SD, while later long-wheelbase cars had the 300 SDL designation. However, when the new Common-Rail Direct Injection engines became available in 2000, they brought with them another new set of suffix letters, the first one being designated an S 400 CDI.

The numbers started off by reflecting the approximate size of the engine. Thus at the beginning of the S-Class period, a 280 S had a 2.8-litre engine, and a 450 SE had a 4.5-litre engine. Exceptions soon arrived, however. Probably unwilling to undermine the prestige of the 450 SE badge, Mercedes chose to call its 1976 big-engined, long-wheelbase derivative a 450 SEL 6.9. The 450 SE and 450 SEL thus remained apparently at the top of the Mercedes range, while the new model was simply a low-volume specialist derivative.

Things subsequently became more complicated. Attracted by the idea of a simplified model-naming hierarchy, Mercedes announced the W140 models as 300 SE, 400 SE, 500 SE and 600 SE types. In practice, the 300 SE had a 3.2-litre engine and the 400 SE a 4.2-litre; but when a new and smaller-engined model arrived, in North America it became a 300 SE 2.8. Logic and consistency, at one time characteristics associated with everything that carried the Mercedes-Benz logo, were beginning to slip away.

The W126 was the longest-serving S-Class, in production from 1979 to 1991.

This was the third-generation car, known as the W140. It proved controversial.

The W220 was the fourth-generation S-Class, and its design focussed particularly on weight saving.

Another problem to arise was that the numbers of the model designations implied their own hierarchy, and the bigger the number, the more prestigious was the model. So when the flagship 6-litre V12 engine was replaced in 1998 by a more powerful 5.8-litre type, the car it powered had to remain an S 600 because ‘S 580’ would have sounded less prestigious. When it was replaced by a yet smaller twin-turbocharged engine of 5.5 litres four years later, the same issue arose, and the flagship model remained an S 600. The range hierarchy argument held sway again when the W221 models were introduced in 1998 with a 3-litre diesel engine: thus instead of becoming S 300 CDI models, they wore S 320 CDI badges because they fitted into the range at the ‘320’ level.

The W221 S-Class built on the advances of the W220 to create the fifth generation of the Mercedes flagship range.

Mercedes-Benz announced the sixth generation of the S-Class in May 2013. The W222 was recognizably related to its most recent predecessors, but was bristling with new technology.

Other Mercedes Factory Designations

Just as the car models have their project codes, so do engines and gearboxes. The engines have three-figure project codes preceded by an M (for ‘motor’, or ‘engine’ – in this case always ‘petrol engine’), or OM (‘Ölmotor’, or ‘diesel engine’). Typical examples are M110 and OM642. The serial numbers often parallel those allocated to the vehicle for which the engine was first intended, but as Mercedes designs engines to be used in as many of its ranges as possible, the link to an S-Class model is not always obvious.

Gearbox type-codes have varied over the years, but usually include a figure that indicates the number of speeds. Thus, automatic gearboxes may have prefix codes W4A or W5A (four-speed and five-speed respectively).

Finally, Mercedes cars are allocated a six-digit Baumuster number. The word stands for ‘build series’, and consists of two elements: the first three numbers are the project code (for example 140 for W140 or C140), and the second three indicate variants. Thus in the case of the W140 cars, 140.042 indicates an S 420, but 140.043 indicates the long-wheelbase version, while 140.050 is for a standard-wheelbase S 500, and so on. The full Baumuster code is incorporated in the chassis or VIN number.

S-Class Assembly

From the beginning, the primary manufacturing centre of the S-Class range has been at the Mercedes-Benz ‘headquarters’ factory in Stuttgart, southern Germany. More specifically, the assembly lines have always been at the factory in Sindelfingen, which is a suburb of Stuttgart some 18.5km (11.5 miles) to the south-west of the city.

The Sindelfingen assembly lines have nevertheless been fed with many components that have been manufactured elsewhere. So for example, the recent OM642 diesel engines have been built at the Mercedes truck plant in the Marienfelde district of Berlin. Other components have been built at some of the many Mercedes factories in Germany, while yet others have been bought in from specialist suppliers; examples of this would be fuel injection and electrical systems that have come in from Robert Bosch AG, and gearboxes that have come in from the Getrag group.

Nevertheless, not every S-Class has been assembled at Stuttgart. For many years Mercedes has operated a number of overseas assembly plants, which assemble its cars from kits of parts sent out from Germany. Many of these plants add locally sourced components, such as glass, batteries and tyres. These operations are known as CKD types (the letters stand for ‘completely knocked down’), and their value is typically twofold: first, they circumvent the taxes that some countries impose on imported cars, so keeping prices to levels acceptable within the local market. Second, they provide employment for local labour, so contributing to the local economy and, ultimately, to its skills base.

It has always been the Stuttgart factory that has built S-Class models for Europe and North America, but there have also been several overseas assembly operations. A factory in Barcelona, Venezuela, served the South American and other markets in the 1970s, and sub-Saharan Africa had cars built at East London in South Africa during the 1980s. In the 1990s, a factory at Toluca in Mexico came on stream to cater for Central and South America, and this was followed by one in Bogor, Indonesia, to serve local markets. The W221 models introduced in 2005 have been built at Toluca in Mexico, at Pekan in Malaysia, and at 6th October City in Egypt.

The AMG S-Class

Tuning specialist AMG was founded in 1968 by former Mercedes engineers Hans-Werner Aufrecht and Erhard Melcher, with the specific purpose of developing high-performance racing engines based on Mercedes production designs. Before long it expanded its operations to include high-performance engines for road-going Mercedes, and by the 1970s was established as the leading aftermarket Mercedes specialist. Originally set up in Burgstall an der Murr, near Stuttgart, AMG moved its headquarters to Affalterbach in 1976.

The company was soon able to exploit demand for modified S-Class saloons: not content with having the most expensive and prestigious saloon on the market, a steady stream of wealthy customers wanted these cars to perform and stop like sports models half their size. But AMG was only too happy to oblige, and as bodykits and customized interiors became fashionable in the 1980s, the company offered conversions to suit, and customers could buy what they wanted from a menu of options. AMG conversions were enormously expensive as well as being engineered to the highest standards.

Inevitably, informal relationships were established between AMG and Mercedes in Stuttgart, although AMG conversions were never ‘official’ in the early years. Then as Mercedes began to take increasing notice of the threat from BMW’s high-performance cars, they made the first step in a series of moves that would lead to AMG becoming the Mercedes equivalent of BMW’s M (Motorsport) division. In 1990, the two companies signed a contract of co-operation, which allowed AMG to sell its products through the vast Mercedes dealer network and also gave Mercedes direct access to the AMG expertise.

The next stage was to develop vehicles jointly, but the first ‘official’ AMG S-Class was not released until 2000, as the S 55 AMG. (The first ‘official’ AMG Mercedes of all was the 1993 C 36 AMG.)

On 1 January 1999, Daimler-Chrysler (as it then was: see the panel below), acquired 51 per cent of AMG shares, and AMG was renamed as Mercedes-AMG GmbH. The racing engine development was at this stage separated from the main business of AMG, having remained at Burgstall since 1976 under the direction of Erhard Melcher, who had resigned as a partner in AMG when the main business moved to Affalterbach. The final step in the saga came on 1 January 2005 when Aufrecht sold his remaining shares in AMG to Daimler-Chrysler, and Mercedes-AMG GmbH became a wholly owned subsidiary of Daimler AG.

Therefore any AMG S-Class made before 1990 was strictly an aftermarket conversion, while those built between 1990 and 1993 were ‘official’ conversions, and those built after 1993 were models that had been jointly developed as performance derivatives of the contemporary Mercedes S-Class range. Though AMG S-Class models are inevitably more numerous and less individualistic than they once were, they have lost none of the exclusiveness and high-performance edge for which the brand has always been famous.

THE MERCEDES-BENZ NAME

It is well known that the Mercedes-Benz brand came into being in 1926, when Germany’s two major car manufacturers, the Daimler Motorengesellschaft and Benz & Cie, merged to keep afloat during a time of economic hardship. Mercedes was the brand name that had been used by the Daimler company since 1901. The merged companies became the Daimler-Benz Aktiengesellschaft, but the Mercedes name was so well known that it was retained as part of the new name for the car manufacturing division – which was, of course, only one element in a much greater industrial conglomerate that also had trucks, trains and marine and aero engines among its products.

In 1998 Daimler-Benz entered a partnership with the American Chrysler company to form Daimler-Chrysler AG. The declared aim was a merger of equals, although it was obvious from the start that the German company was the senior partner. Despite some cross-fertilization between the two product ranges (all to the benefit of Chrysler rather than Daimler), they remained largely separate and the merger was considered a failure. In May 2007, Chrysler was sold off to an investment company, and Daimler-Benz once again became the company behind the Mercedes-Benz marque and its S-Class cars.

What Makes an S-Class?

As the flagship of the mainstream Mercedes-Benz car range, the S-Class inevitably became the model on which new engineering technology was pioneered. Such technology ensured that the S-class name became associated with innovation and trendsetting, and of course the new technology usually found its way down to lesser models in the Mercedes line-up after a few years. It tended to inspire similar developments from other manufacturers, too, which in turn added to the cachet of the original Mercedes achievement.

On the left is the fifth-generation S-Class, the W221, whose production was just ending as this book went to press. As the fourth-generation W220 on the right shows, the car was actually bigger than its predecessor. Both cars were constructed using lightweight materials.

All these factors (see the panel below) were important in building the S-Class image, but equally important was the appearance of the cars – the aspects which in more recent times tend to be grouped under the description of ‘design’. In order to appeal to its intended customers, an S-Class had to have an air of modernity allied to one of timelessness; it had to represent impeccable good taste, and at the same time it had to announce with a degree of discretion that its owner had made a success of himself or herself.

ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE S-CLASS

The S-Class models have always pioneered new technology, and the following are some of the key features that they have introduced.

1978: ABS

Mercedes had been working on the idea of an anti-skid braking system since the 1920s, and had introduced such a system for its trucks and buses in 1970. However, the system was not thought good enough for cars and was held back. The breakthrough came from electronics specialists Bosch, who spent five years developing a digital control unit that would perform reliably in all conditions and was more compact than earlier types. Within five years of its introduction as an extra cost option on the W116 S-Class, ABS had become standard across the Mercedes range.

1979: Offset Crash Capability

Traditional crash tests hurled the car head-on into a barrier. However, Mercedes showed that in most collisions, only half the front of the car hit another object, so requiring the crash energy to be absorbed over a smaller area. This therefore required a stronger passenger safety cell, and the W126 S-Class was the first car to successfully undergo an offset crash test at 55km/h (34mph).

1981: Driver’s Airbag

In 1967, the US government had determined to make airbags compulsory for all new cars from 1974, although in practice that date was repeatedly postponed. One key development difficulty was how to inflate the bag: Mercedes solved it by using gunpowder and a fabric bag. After extensive tests with a fleet of 600 cars to ensure that the airbags did not inflate during normal driving, Mercedes announced airbags (together with belt tensioners) as an option on the W126 S-Class in 1981.

1995: ESP

Mercedes had conceived of a system to deliver failsafe handling, eliminating wheelspin and skidding, many years before its Electronic Stability Programme became available. A rudimentary version called ASR (Anti-Schlupf Regelung, or ‘anti-skid control’) had appeared in 1981, giving some control over power delivery and braking. However, the key to the full ESP system was again compact digital electronics, which could receive signals from the ABS system and instantaneously restrict engine output and decelerate individual wheels until traction was restored.

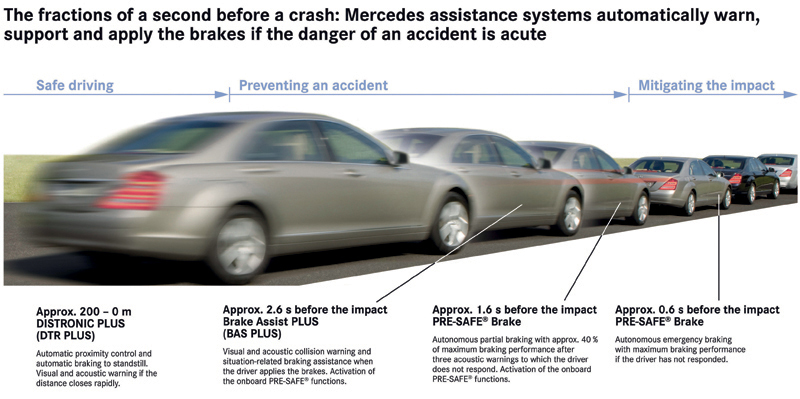

1996: Brake Assist

Brake Assist was capable of recognizing the start of panic braking by means of sensors on the pedal. Most drivers fail to brake as hard as possible until too late, but the brake assist system (BAS) was able to apply full braking at the start of an emergency manoeuvre, so giving the car a better chance of stopping in time to avoid a collision.

1998: Distronic

The Distronic name came by combining the words ‘distance’ and ‘electronic’: by this stage, the importance of English-speaking markets around the world meant that Mercedes gave its new technology English names. Distronic used radar sensors at the front of the car to scan all three lanes of a motorway and help the driver to maintain a set distance from the car in front, so reducing the risk of collisions caused by tailgating. It was introduced on the W220 S-Class, and was later upgraded (as Distronic Plus) to work from lower speeds.

2002: Pre-Safe

The Pre-Safe system used sensors to detect the combination of driving manoeuvres that typically preceded an accident. It then reacted by adjusting various electrically operated items in the car to give occupants the best chance of surviving a collision. So, for example, it moved front and rear seats to positions where the airbags would be most effective, tightened the seat-belt tensioners, and closed the windows and sunroof.

2005: Night View Assist

This system used infrared cameras to relay a view of the road ahead to a screen in front of the driver, so delivering a view of objects further ahead than could be seen unless main-beam headlights were in use.

The S-Class has pioneered many of Mercedes’ accident prevention and mitigation systems.

The S-Class sold very strongly from the beginning; the biggest seller has been the second-generation W126 model, which remained in production well beyond its intended end, for reasons explained in Chapter 3 and Chapter 5. The W140 third-generation range was the least successful, and again the reasons are explained in Chapter 5. Although exact figures for the fifth-generation (W221) model were not available as this book went to press, the upward sales trend begun by the preceding fourth-generation W220 model continued.

| Model | Production years | Total | |

| First generation | W116 | 1972–1980 | 473,035 |

| Second generation | W126 | 1979–1990 | 818,068 |

| Third generation | W140 | 1991–1998 | 406,717 |

| Fourth generation | W220 | 1998–2005 | 484,697 |

| Fifth generation | W221 | 2005–2013 | 500,000+ |

Sales of the S-Class coupés (and their CL-badged successors) have been considerably smaller, as is to be expected of such models. Note that there were no coupé derivatives of the W116, and so the first-generation S-Class coupés were sold alongside the second-generation S-Class saloons, and so on.

| Model | Production years | Total | |

| First generation | C126 | 1981–1991 | 74,062 |

| Second generation | C140 | 1992–1998 | 26,022 |

| Third generation | C215 | 1999–2006 | 47,984 |

| Fourth generation | C216 | 2006–2014 (?) | Not available |

Once the original W116 S-Class had encapsulated all these requirements, it became a formidable task to design and engineer the series of cars that replaced it. Although the technical and design supremacy of the S-Class is something that car buyers around the world tend to take for granted, developing a new model is a massive responsibility and a hugely expensive task for the company, and nobody should be in any doubt about the talent and expertise that are required to achieve it. Though there have been repeated attempts by other car manufacturers to break the S-Class’s stranglehold on its market – and many of these have been excellent cars in their own right – the S-Class magic has so far remained virtually unassailable.

Only once has the S-Class faltered, and that was with its third incarnation, the W140. Delays in bringing it to market (largely prompted by the actions of a rival manufacturer) meant that the car was out of step with its times when it arrived in 1991. At Stuttgart, the fallout was immense – although researchers will look in vain for any reflection of that in official pronouncements of the time, or indeed official pronouncements since. Vast sums of money had to be spent to keep the S-Class in its position as the world’s favourite luxury car; major revisions to the car itself were followed by discounting activity and a number of other actions about which information is only now becoming available. Among the engineering and design teams, heads most certainly rolled, and as Chapter 5 suggests, the initial failure of the W140 was at least partially responsible for far-reaching changes to the whole product strategy of the Stuttgart passenger car division. More than anything else, this reflected how important the S-Class had become to the company by the start of the 1990s.

The S-Class and the Future

As it has done since the 1970s, Mercedes continues to use cars based on current-production S-Class models to demonstrate new technology and new ideas. Whether or not the new technology becomes available, these concept cars and experimental vehicles help to keep the association of the S-Class with pioneering design and technology firmly in the public consciousness.

The Ocean Drive Concept

At the Detroit Motor Show in January 2007, Mercedes displayed a strikingly attractive concept for a four-seater luxury convertible. It was known as Concept Ocean Drive, and was unashamedly aimed at wealthy Californian buyers.

The car was based on the long-wheelbase S 600 platform, and like all Mercedes concept vehicles, was drivable – at least at town speeds. One story suggests that the design was originally intended as an addition to the Maybach range. It was nevertheless presented as a Mercedes, with the pillarless construction typical of Mercedes coupés. The shape of the dashboard and the switchgear were very much in the S-Class style, and the more upright grille previewed the new style that would appear on the W204 C-Class cars later that year.

Built in 2006 on a W221 S 600 platform, this was the Ocean Drive concept.

The Ocean Drive had some typical show-car features, such as LED head- and tail-lamps, 21in alloy wheels, and powered drawers in the rear that revealed a champagne bottle and glasses to rear-seat occupants.

ESF 2009

ESF 2009, an experimental safety vehicle shown at the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV) Conference in Stuttgart on 15 June 2009, was the first ESV from Mercedes since 1974 (see Chapter 2). Based on an S 400 Hybrid, it featured more than a dozen safety innovations, most of them fully functioning in demonstration mode, and suggested what Mercedes might have in mind for its future cars. Its key innovations were as follows:

■ Pre-safe structure: inflatable metal structures that were stored in a folded condition but were inflated rather like an airbag in crash conditions in order to give additional protection.

■ Braking bag: an auxiliary brake accommodated in the floor that was deployed when a crash was inevitable; it used a friction coating to stabilize the vehicle against the road surface and improve deceleration.

■ Interactive vehicle communication: this enabled the vehicle to transmit warnings about weather conditions or obstacles on the road to other vehicles equipped with the technology.

■ Pre-safe pulse: used the air chambers in the bolsters of the seat backrests to move the seat occupants up to 50mm nearer the centre of the vehicle in a side impact, so reducing forces acting on their torsos by up to a third.

■ Spotlight lighting function: activated by the infrared camera of Night View Assist Plus, which allowed a partial LED main headlight beam to illuminate potential hazards beyond the normal reach of the main beams.

Among the innovations on the W221-based ESF 2009 was a so-called ‘braking bag’, carried underneath the car and released to help slow the vehicle in an emergency.