1

A Double-Consciousness

It is simply not possible to act in good faith toward people one does not respect, or to entertain hopes for them that are appropriate to their gifts.

Tradition is the living faith of the dead, traditionalism is the dead faith of the living.

I am nature.

On entering college, the first art survey course that I elected to take introduced art majors to the modern and late modern periods. Since our syllabus began with abstract expressionism, it made sense to study Willem de Kooning’s controversial painting Woman II (1952) early in the semester (see plate 1).1 I loathed de Kooning’s painting. Projected larger than life on the screen before us, the sneering grin of de Kooning’s subject, the painting’s aggressive sexuality, its looming chaos and simmering rage affronted my sensibilities. And a rapid sequence of questions followed. Why had our professor granted de Kooning’s painting such elevated status? Was the painter advancing some new female archetype, or was he just a misogynist? In fact, the answers to these kinds of questions interested me, but they paled in comparison to my growing worry that I was being played the fool. To gain a sense of the anxiety I felt as an incoming art major early in the 1970s, a bit more biography will help.

The medium-sized state university that I attended was located in a small Midwestern town. At the time my notions about art were admittedly romantic. Art, I thought, was primarily about self-expression, and the images and objects that held my interest ranged from Monet paintings to Maxfield Parrish illustrations and from psychedelic head shop posters to wheel-thrown pottery (it was the 1970s, after all). While conceptual projects held some interest, it was realism—the verisimilitude generated by a skilled hand moving in concert with a keen eye—that impressed me most. I had yet to genuinely consider artists such as Jasper Johns, Louise Nevelson, Barnett Newman, Georgia O’Keefe, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, Mark Rothko, Richard Serra and Andy Warhol. Moreover, the irreverence of the New York art scene, the authority of critics such as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, and the radical departure of modern art from the traditional canon existed for me at some far reserve either in the pages of Artforum or on the walls of museums that I had yet to visit. In brief, I was ill-equipped to give an account for my intense dislike of de Kooning’s Woman II.

As the semester advanced, however, my initial foreboding turned to curiosity. I largely credit my professor for this change. Sporting wire-rimmed glasses and a flowing beard, he embodied what I liked most about the American counterculture. My professor’s congenial nature and wry wit drew me in, and before long his enthusiasm for “difficult” art disarmed my skepticism. I was coming to understand and then believe that challenging modern and contemporary work could be a critical point of entry into substantially larger conversations about personal and cultural meaning.2 I was intrigued.

A FALSE CHOICE

Learning to draw, comprehending color theory and grasping the elements of basic design, not to mention the intellectual discourse that surrounds them, are formidable tasks. But for evangelicals who came of age during America’s postwar years, there was an added pair of challenges. On entering most secular art academies or university art departments, these Christian students quickly discovered that their religious convictions were thought to be hopelessly naive. And to the degree that these same students exhibited signs of religious devotion—something weightier than mere assent to creeds, traditions and stories—they would almost certainly encounter art world scorn. By the close of the twentieth century, this pattern remained largely in force. Writing in 2014, art historian James Elkins simply confirms the ongoing presence of this secular bias: “Straightforward talk about religion is rare in art departments and art schools, and wholly absent from art journals unless the work in question is transgressive. Sincere, exploratory religious and spiritual work goes unremarked.”3 Sadly, this discriminating spirit was paired to another: the Christian community’s ambivalence toward or disapproval of the visual arts. Postwar conservatives regarded the visual arts as a curious vocation at best and a capitulation to worldliness at worst.

However, as Dutch historian and philosopher Gerardus van der Leeuw points out, the edgy tension that existed between evangelical religion and the art world is hardly new. This, he explains, is because “religion is always imperialistic. No matter how vague or general it may be, it always demands everything for itself.”4 Critics of religion will eagerly agree. But, cautions van der Leeuw, “Science, art, and ethics are also imperialistic, each in its own right, and also in combination with the others.”5 Van der Leeuw’s point is that practitioners of religion, science, art and ethics each believe that their discourse offers the most comprehensive and, therefore, superior picture of reality. And so it follows that in the modern development of professional disciplines, art is no more eager to submit to religion than religion is willing to yield to art. Within this oppositional framework, each camp exerts pressure on its practitioners to abandon pursuits that lie beyond the parochial interests of their guild.6

The most tragic fact about the conflict, which we will explore in this book, is that it is based on a false choice. Again, as van der Leeuw explains it, “The paths of religion, art, ethics, and science not only cross, they also join.”7 In this same spirit, philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff insists, “Art and religion are inextricably bound.”8 Material culture bears witness to this reality. Across time, the business of fashioning things, crafting narratives, inventing rituals and designing spaces has been the domain of both art and religion. A casual stroll through the collection of any major art museum confirms that, since the beginning of recorded history, art and religion have been partners in an ongoing dialogue on everything from the character of vocational pursuits and the demands of daily life to more lofty speculations concerning the nature of suffering and evil, love and beauty, and transcendence and eternity. Simply put, there is ample reason to insist that the modern antagonism between art and faith is a late nineteenth- and twentieth-century aberration.

In his review of Seeing Salvation: The Image of Christ, a major exhibit at the National Gallery in London in 1997, Bryan Appleyard argued, “Western art was Christian, is Christian and, for the foreseeable future, can be only Christian; we cannot evade the Gospel’s continuing presence in our culture. Their meanings, their imagery, have determined the way we think, the way we create.”9 It is not difficult to locate the genesis of the long period that Appleyard points to. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity early in the fourth century turned the whole of the Roman Empire from polytheism and secularism toward Christian theism.10 Because of his edict, the minority voice and standing of the Christian community—the one that we learn of in the book of Acts and the Pauline Epistles—was reversed so that Christianity would grow to become the official religion of the Roman Empire. For at least thirteen centuries this worldview galvanized Western thought and practice. Secular thinker Alain de Botton characterizes the long-standing reciprocity between art and the church like this: “Intriguingly, Christianity never expected its artists to decide what their works would be about; it was left to theologians and doctors of divinity to formulate the important themes, which were only then passed on to painters and sculptors and turned into convincing aesthetic phenomena.”11

As already indicated, contemporary experience has led many to conclude something quite different than what van der Leeuw, Wolterstorff, Appleyard or even de Botton have described. Modernism signaled an end to a long and widely held conviction that the universe is best understood as a created unity. But as Daniel H. Borus points out, “The more the world resembled a multiverse rather than a universe, the greater the appeal of heterogeneity became in explanations and interpretations.”12 As philosopher Charles Taylor explains in his masterful study The Secular Age, moderns came to regard the universe as a disenchanted place.13 With this move from the sacred to the secular, the larger narrative that once made it possible to discuss the meaning of human life in relation to the whole of created reality vanished entirely. Art historian Kathleen Pyne describes the contours of the modern mind that emerged: “The modern cosmos is usually construed as a world in which the center no longer holds things together. It is a world that only capriciously reveals its true reality to humankind, with the consequences that human experience is often contradictory and irrational, and uncertainty rules moral and religious life.”14

Those who believe that Appleyard’s claim about art and religion in the West is correct lament the loss of enchantment in our secular age. Nonetheless, and while it is ever tempting to romanticize the past, it would be foolhardy to deny the checkered history of the West: its savage ideological conflicts, immeasurable bloodshed and manifold abuses of power. In more than a few instances, it was the church that sponsored these horrors. And along the way some of its clerics and theologians viciously assaulted artists in spirit and sometimes in body. Meanwhile, it would be equally foolish to propose that prior to modernism the West was populated by a whelming throng of religiously devout Christians who loved the visual arts. It is more reasonable to propose that, where art and religion are concerned, a multitude of diverging theories and opinions regarding the meaning and practice of each in relation to the other is standard fare.

These cautions notwithstanding, it surely is the case that modernism was conceived and advanced by public intellectuals and cultural elites who were eager to embrace nontheistic thought. Political analyst David Brooks summarizes this secular project as follows:

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, religion lost influence, but the religious impulse lingered on. Some people sought salvation in the secular religions of politics—in Communism, fascism and various utopian experiments. Others saw artists, musicians and writers as Holy Men, who could provide transcendence and meaning, revealing timeless truths on how to live.15

The radical change that Brooks describes was evident as early as 1911 in an exhibit organized by Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and Gabriele Münter. Other modernist participants in the exhibit included the recently deceased Henri Rousseau and musical composer Arnold Schoenberg, a talented amateur painter. As historians readily point out, the “essential idea” that lay behind this group known as Blau Reiter (Blue Rider) “was Nietzsche’s dictum that ‘Who wishes to be creative . . . must first blast and destroy accepted values.’”16 According to historian Allan Megill, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) conceived “of ‘nature’ and of ‘the natural’ as human creations. In his view, the world in which we live is a work of art that is continually being created and recreated; what is more, there is nothing either ‘behind’ or ‘beyond’ this web of illusion. . . . The world is ‘a work of art’—but one that, as a consequence of the crisis of God’s death, ‘gives birth to itself.’”17 And here I add poet Christian Wiman’s prescient observation: “As belief in God waned among late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century artists, death became their ultimate concern. . . . Postmodernism sought to eliminate death in the frenzy of the instant, to deflect it with irony and hard-edged surfaces in which, because nothing was valued more than anything else, nothing was subject to ultimate confirmation or denial.”18

Artist by artist and movement by movement, early modernists ushered in what art historian Robert Hughes termed “the shock of the new.”19 As Brooks suggests, the artist and her vocation would supplant the long-standing cultural agreement that God’s divine agency and rule was the prime moving force behind the universe. As nineteenth- and twentieth-century secularists jettisoned religion, they embraced aesthetics as their means to establish a cultural foothold. In service to this cause, a struggle for creative emancipation ensued, during which time-honored virtues such as truth, goodness and beauty were subject to considerable scrutiny and then either relativized or discarded. Whether by design or default, this position left twentieth-century artists operating at the forefront (hence the term avant-garde) of cultural chaos. The artists’ aggressive dismissal of absolutes—in every form—anticipated the social and intellectual realities of the postmodern condition that would follow.

Protestant conservatives, meanwhile, steeled themselves against these radical developments. To that end, American evangelicals chose the language of theology and especially the Bible to maintain what they regarded as moral and spiritual high ground. Moreover, while upholding their Reformational commitment to sola scriptura (Scripture alone), they maintained its aesthetic—a fundamental hostility to the use of painting and sculpture in their houses of worship.20 By mid-century the schism between modern art and evangelical piety was simply assumed. In the decades that followed, this standoff might be caricatured as follows: If to the secular mind the art world appeared clever, visionary and provocative, then to evangelicals it was the personification of narcissism, profanity and godlessness. And if to pious Christians the church-gathered felt like a safe haven of mercy, moral stability and spiritual succor, then to artists it seemed xenophobic, pedantic and hypocritical.

The balance of this chapter describes the shared cultural context during America’s postwar period, wherein both the art world and the evangelical church “came of age.” Notably, leaders in both movements championed utopian visions even as they faced innumerable dystopian realities that threatened to undo their respective programs. If one group hoped to navigate the yawning spiritual gap that lay between the shining city of God and the depraved condition of humanity, the other wrestled in the liminal space that existed between the brilliance of the creative spirit and the nagging desire for existential significance.

POSTWAR AMERICA

In the aftermath of two world wars and the financial upheaval of the Great Depression, from 1945 onward America enjoyed a season of peace and prosperity. Veterans on the GI Bill filled college classrooms to capacity, suburban development sprawled, home ownership burgeoned and the boomer generation was born. American enterprises in business, industry, education and science prospered, first at home and then abroad. The early postwar years gave rise to sleek automobiles, streamlined appliances, towering skyscrapers, interstate highways—all built, so it seemed, from Bakelite, plastic, concrete, chrome and steel.21 As fresh brands sought greater market share, new logos, billboards and advertisements generated vivid icons befitting the modern age. Aided by an explosion of newsstand tabloids and radio, a meteoric ascendancy of popular culture would follow. A new class of celebrity athletes, artists, movie stars, musicians and politicians gained an admiring public, and it seemed as if their skyrocketing fame, dramatically accelerated with the advent of television, would know no bounds.

More than any other artist of the day, Andy Warhol (1928–1987) memorialized the rapid growth of this broad-reaching, celebrity-obsessed, visual culture. Warhol possessed the uncanny ability to capture the place where popular culture, commerce and art intersect. Images like his serigraph Marilyn (31) (1967) depicted the glitz and glam of the Hollywood spectacle, all the while hinting at the existential void that lay beneath it (fig. 1.1).

1.1. Andy Warhol, Marilyn (31), 1967

But as US citizens pursued the “good life,” a lurking menace challenged the promise of the American dream—Soviet communism. Indeed, the theaters of war had opened new commercial markets, the heightened possibility for international cultural exchange and unprecedented opportunities for nation building. But these global conflicts also occasioned new threats. And so, even as America’s bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima had signaled an end to World War II, the presence of this weaponry subsequently launched an arms race between superpowers, and the atomic age was born. In short order the Soviets armed themselves with nuclear warheads and intercontinental missiles, and within a decade every corner of the globe was susceptible to the threat of annihilation. With the escalation of the bitter and protracted Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, a disquieting version of Marshall McLuhan’s “global village” settled in.

The desire of the Soviets for world domination was especially troubling to the Christian community and for good reason: not only was communist aggression another hideous iteration of the very totalitarianism that had been vanquished in the Allied defeat of Hitler’s Third Reich, but its ideology was atheistic in every respect. In fact, Stalinists and the Soviet regime that followed would torture, imprison and kill tens of thousands of believers. This persecution extended far beyond Soviet borders to the Eastern bloc, China, North Korea, Southeast Asia and even Cuba. While Marxist theorizing established the careers of some armchair academics, the real-life use of communism to oppress common folk in the second half of the twentieth century was unprecedented. It is small wonder that many patriotic churchgoers understood America to be God’s nation on a mission to protect the world from “godless” communism.

This commingling of politics and religion in America had direct bearing on the art world. For even as many artists had fled three decades of European mayhem and violence for the promise of creative freedom and relative peace in the United States, at the height of the Cold War, political conservatives—most notably, US Senator Joseph McCarthy—routinely discredited contemporary artists by branding them as communists. Some were.22 Sadly, a battle line was drawn between those who welcomed the alignment of evangelical religious belief with right-wing political rhetoric over against more liberal-minded citizens who did not. And almost without exception, artists belonged to the latter.

As Cold War rhetoric and tactics continued to dominate US foreign policy, unrest at home began to stir. The catalyst for this turmoil was multifaceted: growing tension in black/white relations, ambitious new social programs outlined by Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, an ill-defined and ultimately failed war in Vietnam, and the overreach of the nation’s powerful military industrial complex. Emerging from this was a vocal youth culture that “partied” beneath the banner of “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll” even as it embraced radical, left-leaning social and political ideals that had been gathered up in the classrooms of America’s leading universities. In ways that might not have been predicted, theory had moved to praxis so that whether one belonged to the establishment, the radical left, or the ambivalent middle, by the early 1970s dynamic social change encompassed the whole of American culture, including the precincts of art and religion.

If in the early decades of the twentieth century the modern art movement and the evangelical church were both cultural outliers, by the century’s end they would come to occupy a place of prominence in contemporary American life.23 For their part, many evangelicals believed that they had awakened the conscience of a so-called moral majority, others built megachurch congregations and still others entered headlong into conservative politics. Meanwhile, art world aesthetes personified high culture. Their wealthy patrons constructed or expanded contemporary museums in urban centers worldwide, and blue-chip artists enjoyed record sales and commissions. Remarkably, the elasticity of the American democratic ideal—its toleration—allowed both to prosper. And as the United States grew to become the world’s sole superpower, both its art and its religion commanded international attention.

Having acknowledged the dynamic social and political change that swept America during the postwar period, let us press on to explore the posture of the secular art world and the conservative Protestant church regarding their respective cultural standings, religious beliefs and convictions about personal and social transformation.

HIGH OR LOW

In 2006, hedge-fund manager Steven Cohen acquired Willem de Kooning’s Woman III (1952–1953), a painting belonging to the series mentioned in the opening paragraph of this chapter, for $137.5 million. If the sum of Cohen’s investment was remarkable, it was not out of step with art market trends. In her book Seven Days in the Art World, Sarah Thornton notes, “In 2007, Christie’s sold 793 artworks for over $1 million each.”24 When patrons like Cohen purchase works of art for record-setting amounts, the value and critical importance of these objects increase. While it may be that the art world is defined more by market forces than aesthetics, wealthy financiers are not the sole arbiters of taste. Rather, their judgments are enmeshed with the assessments of a small coterie of prominent visual artists, gallery dealers, auction-house experts, art historians, critics and publishers. Together they comprise what is commonly termed the “art world.” According to Thornton, this world is “structured around nebulous and often contradictory hierarchies of fame, credibility, imagined historical importance, institutional affiliation, education, perceived intelligence, wealth, and attributes such as the size of one’s collection.”25

Pertinent to the concern of this book, the lineaments of the art world invite at least three observations. First, consider its bearing on individual artists. Of the hundreds of thousands of artists hoping to attract serious critical attention, most will never enter the sitting rooms, galleries and collections of the powerful, and fewer still will be awarded exhibits in important venues, handsome exhibit catalogs or six-figure sales. Artists with MFAs from reputable schools, productive studio practices and solid but mid-level exhibition records will not make the cut.

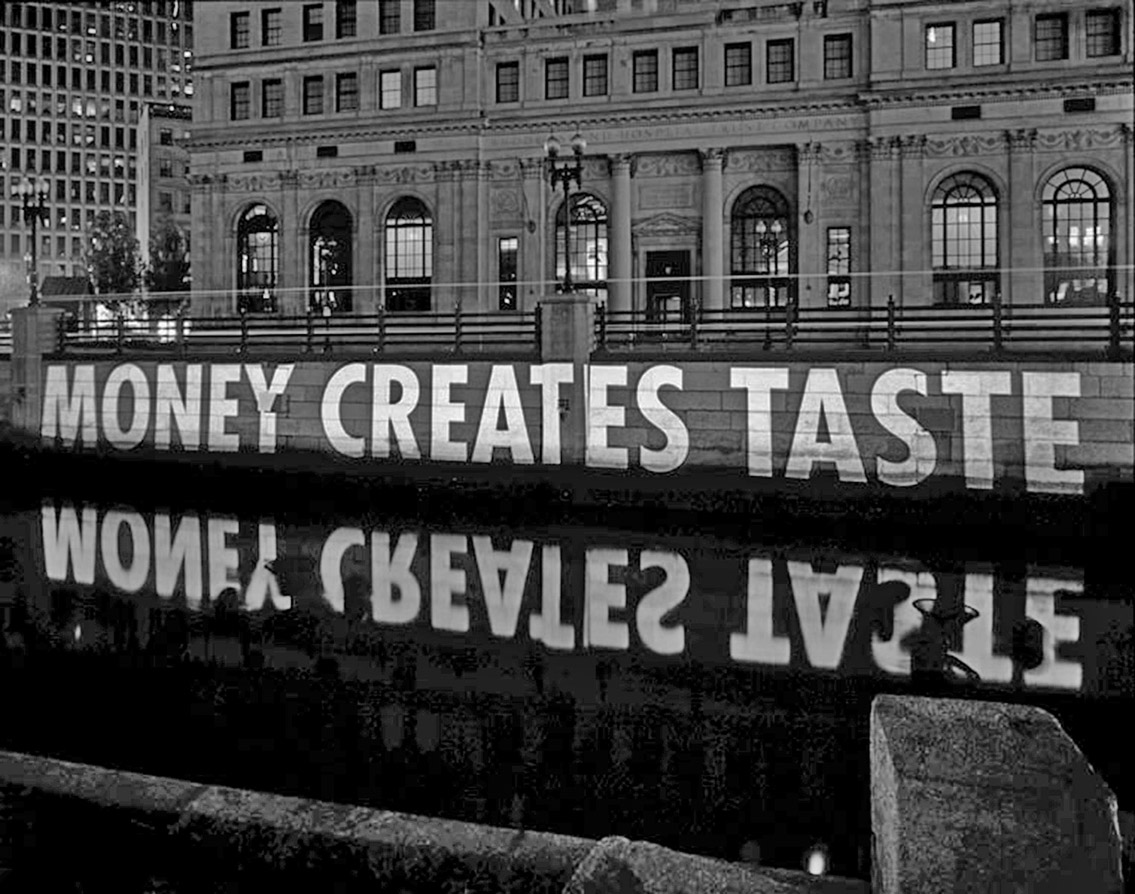

1.2. Jenny Holzer, Money Creates Taste, projection

Second, these art world machinations are not appreciably distinct from the elitism that exists in business, education, entertainment, law, medicine and professional sports. At their best, these guilds advance talent, innovation and excellence; they encourage the cream to rise. At their worst, these same guilds (formal and informal) perpetuate self-interest and haughty disregard for those who do not belong to their tribe—the uninitiated, unlearned and uninformed. In this respect the “exceptionalism” of the contemporary art scene can seem especially bizarre since it appears ever ready to sponsor projects that many citizens find esoteric, ugly or even profane.26

This leads to a third observation: if queried, most Americans would claim that the art world has no bearing on their daily lives; the enterprise does not summon their regular conscious concern or attention. In fact, galleries, museums and patrons join other elites in shaping the civic fabric of the world’s most vital urban centers. William Deresiewicz writes:

After World War II in particular, and in America especially, art, like all religions as they age, became institutionalized. We were the new superpower; we wanted to be a cultural superpower as well. We founded museums, opera houses, ballet companies, all in unprecedented numbers; the so-called culture boom. Arts councils, funding bodies, educational programs, residencies, magazines, awards—an entire bureaucratic apparatus.27

Whether it is provocative new museums, edgy contemporary exhibits or monumental commissions, the architects, artists and curators who envision these, in tandem with their sponsors, are caught up in a whirl of creative and commercial ventures that affect everything from graphic design to fashion and from product development to the contours of urban life. Consider, for instance, Alain de Botton’s reflection on the social and even religious function of today’s art museums: “The best architects vie for the chance to design these structures [art museums]; they dominate our cities; they attract pilgrims from all over the world and our voices instinctively drop to a whisper the moment we enter their awe-inspiring galleries. Hence the analogy so often drawn: our museums of art have become our new churches.”28

The trio of realities described above underscores the top-down nature and operation of the art world. By contrast, evangelical programs are essentially bottom-up, and in this regard their broadly conceived mission embodies three cardinal convictions that are substantially distinct from those held by the art world.

First and foremost, evangelicals long to see the unchurched and unconverted place their faith in Jesus Christ. In their view, the only cure for “sin sick” souls is Christ’s atoning death on the cross. Typically, they regarded this gift of salvation—God’s gracious pardon from sin—as a personal transaction between God and an individual person.

Second, evangelicals believe that all who confess Christ are welcome at the foot of his cross. The good news, God’s “amazing grace,” extends to every tribe, tongue and nation so that in Christ “there is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male or female; for all . . . are one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28).

And third, since evangelicals believe that the eternal destiny of each person hangs on their response to God’s gracious invitation and that this message is good news for all people, there can be no more urgent task than to bear witness to this new life in Christ. Indeed, before he ascended to heaven, Jesus instructed his disciples to “make disciples of all nations” (Mt 28:19). Postwar evangelicals embraced this command—the Great Commission—as their own.

Generally speaking, evangelicals’ eagerness to convert the lost oscillated between their deep desire for family, friends and neighbors to enter into a life-giving relationship with Christ and strategies intended to reverse secularism and re-Christianize America. Following World War II, the challenge of sharing Christ grew to become a global concern that stimulated a generous outpouring of finances and fervent prayer. These words from Harold Ockenga’s convocation address at Fuller Theological Seminary in 1947 capture the spirit of these years as well as any:

Listen to me, my friends, the quickest way to evangelize the world, the quickest way to enter the open field, the quickest way to do God’s work in the period of respite before us, before another holocaust takes place that everybody is predicting now, and only a few did some time ago, is to have divinely called, supernaturally born, spiritually equipped men of unction and power to go forth. We will not default. God help us, we will occupy till he comes.29

To carry out this evangelical vision, passion for evangelism was paired with American know-how, confidence and techne. Adding yet more urgency to this endeavor was the widely held belief that Christ’s return could be hastened if the task of world evangelization were “completed in this generation.”

As I have described it, the art world is largely an elitist enterprise centered on the wealth, talent and aesthetic preferences of a few, and later in this chapter I examine the mind and motives of several prominent modernist artists. In sharp contrast to that social order, postwar American evangelicalism was a grassroots, populist movement. To understand something of the contours of the evangelical mission during those years, consider the life and practice of Billy Graham and Bill Bright, two men who epitomized the effort.

By any standard, Billy Graham (b. 1918) was the twentieth century’s most famous evangelist—perhaps the century’s most famous citizen. He sought nothing less than to preach the gospel to all men, and to that end he filled stadiums and arenas with tens of thousands of listeners the world over. It is estimated that during Graham’s years of active ministry the evangelist reached more than two billion people both in person and via radio and television. Hollywood stars, high-profile athletes and US presidents sought his counsel, and not infrequently even his detractors admired him. Graham was handsome, well-spoken, and the picture of integrity, all of which added to his appeal. Ironically, the evangelist’s sharpest critics seemed to be Christian fundamentalists who regarded his fraternization with liberal Protestants and Catholics the evidence of worldly compromise.

Businessman Bill Bright (1921–2003), founder of Campus Crusade for Christ, shared Graham’s commitment to world evangelization. In 1952 Bright created the Four Spiritual Laws, a gospel booklet designed to present the logic of the Christian message in simple terms, initially to college students (fig. 1.3). The tract’s central point was this: “We must individually receive Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord; then we can know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.” The form and content of Bright’s Four Laws were not appreciably different from a booklet of coupons inserted in one’s Sunday paper. Millions of copies were printed and, largely because of Bright’s charismatic leadership and business acumen, hundreds of thousands of persons were trained to present this outline to friends and strangers alike. Enthusiasts of the Four Laws are eager to point out that Bright’s tract has been used by God to lead many to Christ.30

1.3. Cover of Have You Heard of the Four Spiritual Laws? by Bill Bright, 1965

Where cultural elites are concerned, two responses to these kinds of evangelical efforts are worth noting. Whether it was Graham’s simple plea at the end of each crusade to “come forward and receive Christ” or Bright’s low-brow gospel tract, these approaches to witness supplied ample evidence to elites that evangelical Christianity was surely not for them. Added to this, the insistence by these same evangelicals that Jesus was the only way to the Father was and remains intolerable to the liberal mind.

Meanwhile, though evangelicals like Graham and Bright enjoyed considerable popular success, a good many evangelical leaders grew increasingly frustrated by their exclusion from centers of cultural power. If some regarded this rejection as “suffering for the sake of Christ,” others could not mask their longing to “take back the White House,” “transform the secular university,” “redeem Hollywood,” and so on. Remarkably, in their desire to amass cultural capital, neither fundamentalists nor evangelicals demonstrated any appreciable interest in the visual arts.

In their desire to reach the world for Christ, almost without exception, early postwar evangelical strategies for witness failed to anticipate the advent of pluralism. By the close of the century, however, the realities of an emerging global culture necessarily affected every aspect of the evangelical mission both at home and abroad.31 The new heterogeneity took up residence not only in America’s urban centers but also in its suburbs. To their credit, more progressive evangelicals responded by contextualizing their message and methods, and their sensitivity to matters of race, gender, traditional cultures and even social class increased. It followed that apologetic arguments would, more and more, be intentionally paired with what was surely the most unimpeachable aspect of the evangelical witness—feeding, clothing, housing and educating millions of children, women and men, and often at considerable cost. But even this responsible social action would not diminish the long-standing tension between the conservative church and the dynamic world-changing culture that seemed to flourish beyond its doors.

More than six decades ago, H. Richard Niebuhr’s (1894–1962) book Christ and Culture outlined this dilemma. Niebuhr proposed five possible relationships: Christ against culture, the Christ of culture, Christ above culture, Christ and culture in paradox, and Christ the transformer of culture.32 Whether one’s posture toward culture is primarily top-down or bottom-up, the range of Niebuhr’s positions confirms the breadth and complexity of the situation.

Though they themselves would have been disinclined to read the work of this neo-orthodox theologian, twentieth-century fundamentalists and some of their evangelical heirs are best described by Niebuhr’s first position, Christ against culture. This view was well matched to their separatist doctrine, and it had compelling biblical warrant. That is, beginning with the people of Israel and their emancipation from the land of Egypt and continuing on to the early church in the New Testament, God frequently commanded his people to be distinct in belief, character and behavior from the pagan nations that surrounded them. Jesus’ own teaching concerning the kingdom of God and the kingdom of this world effectively underscores the idea of two cultures in conflict. It was Jesus, after all, who described Satan as the “ruler of this world” (Jn 12:31).

However one assesses Niebuhr’s Christ-against-culture position, the most persuasive aspect of this position is its capacity to call evil “evil.” Whether high or low, human culture never ceases to generate dubious, harmful and even blasphemous things. Even the most ardent, irreligious person must concede that “worldly temptations” such as alcohol, drugs, gambling, infidelity, pornography and tobacco have devastated millions of lives and that the “idols” of fame, money and power have been the ruin of countless families, communities, guilds and nations. The biblical antidote to this unrighteous mayhem is to resist evil or, in Old Testament language, to separate what is “clean” from that which is “unclean.” Consider the words of James 4:4: “Adulterers! Do you not know that friendship with the world is enmity with God? Therefore whoever wishes to be a friend of the world becomes an enemy of God.” But how is this separation to be accomplished?

In his day, and desiring to cleanse Florence of its worldliness and to reform the church, the fifteenth-century Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola gathered up thousands of objects that he regarded as immoral—everything from pagan texts and art to mirrors and cosmetics that only the city’s wealthiest citizens could have afforded—and set the entire pile ablaze. The event known to us now as the Bonfire of the Vanities occurred on February 7, 1497.33 Curiously, the actions of this Catholic friar who knew and highly regarded the work of Fra Angelico would foreshadow the evangelical proclivity, centuries later, to ban or burn books, record albums and CDs; boycott offensive Hollywood films; and protest the exhibition of blasphemous works of art—works they had not personally viewed that were created by artists whom they did not know.

The evangelical desire for personal piety merits a bit more comment. Twentieth-century Protestant conservatives rightly understood that any meaningful Christian doctrine must find palpable connection to daily life. They reasoned that the relativism of the day could be countered only by a renewed commitment to the Bible as truth. Meanwhile, in the secular world, traditional conceptions of family and morality, especially sexuality, were being overturned at an alarming rate. In other words, even as private spiritual practices such as prayer, Bible reading and personal holiness were belittled, it seemed that moral absolutes were slipping away. If secularists and liberal Christians had stridently embraced worldliness, evangelicals would stand their ground. Some conservative Protestants were content simply to “be separate.” Others, however, prepared for battle, and to that end they assembled a moral arsenal composed of censorship, mediated social pressure and political action. From the mid-1980s onward, Christian and secular social observers would note (sometimes with considerable delight) the ever-widening gulf between these two camps, and the postulation of a great “culture war” became a handy and fashionable means to describe it.34

Whether evangelical acts of resistance were prudent must be evaluated, but in every age the church has needed to embrace internal reform even as it steels itself against its external challengers. In modern America it was religious sects such as the Amish and certain Catholic orders that managed to separate themselves most completely from the world. But these measures were too austere for most postwar evangelicals, who instead advanced the idea that one could participate in the world while somehow managing not to be of it. On first impression this approach appeared practical and even wise. But almost without fail, implementation of this “in but not of” strategy generated a graceless legalism. As fundamentalists and evangelicals upheld their doctrine of separation, they faced the challenge of working out this separation in a world where the assumptions of Christendom rapidly receded as the social and ideological complexities of pluralism gained ascendancy.

Again, while there is much to commend the Christ-against-culture position, it contains a deeply flawed conception of culture (not a flaw in Niebuhr’s reasoning, but rather in the reasoning of those who held the position he described). As a synonym for worldliness, Christian conservatives have understood culture to be a Babylon given to the worship of false deities, the pursuit of godless passions and a safe haven for the enemies of our soul (Rom 1:18-32). Viewed through this lens, culture becomes an artifact of human activity used to describe those who live opposed to God and decidedly not the natural outcome of our being creatures whose domain is creation. Theologically speaking, the oppositional view of human culture is entirely postlapsarian: culture is the result of Adam and Eve (humanity) reaping their just reward for their rebellion against God rather than a mandate given by God to the man and the woman to rule and be fruitful amid Eden’s paradise (Gen 1:26-27).

In sharp contrast to evangelical hand-wringing about purity and holiness, the art world has never been much troubled by its relationship to culture: its primary task is to create culture. It is at this point in our discussion that the deep sociological divide between art world elites and the evangelical church becomes most apparent. Whether liberal or conservative, both were well practiced at separating sheep from goats as a means to advance their respective causes.

It is, for instance, no secret that secular elites delighted in discrediting evangelicals. To this end they constructed truncated histories of conservative Christianity in America. Such a history might begin by citing Jonathan Edwards’s sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” (1741), go on to celebrate William Jennings Bryan’s defeat in the Scopes (Monkey) Trial (1925) and chortle at televangelist Jim Bakker’s moral and financial indiscretions (1989). Predictably, these narratives and their endless iterations culminate with an expression of disdain for James Dobson and his organization, Focus on the Family. That these “bad histories” span nearly three centuries and feature protagonists who exist in no particular relationship to each other did not undermine the overarching goal of this effort, which was to demonstrate that evangelicals are plain folk, simple in mind, lacking urbanity and foolishly devoted to superstitious belief.

Meanwhile, evangelicals were no less swift to judge. In their view, secular elites were blithely unconcerned about the needy, given to habitual self-aggrandizement and rushing pell-mell on the “wide way” to their own destruction. Evangelical pronouncements concerning the art world have been equally vicious: artists are rebellious bohemians, collectors are hoarders of art-world treasure, and patrons are narcissists who spare no expense to erect extravagant monuments to themselves.35

Fortunately, postwar America was both more complicated and more interesting than simple binary schemes like high and low might suggest, and from time to time these tidy classifications collapsed entirely. For instance, in the late 1970s, Christian Reformed pastor Robert H. Schuller (1926–) commissioned world-renowned architect Philip Johnson (1906–2005) to take the lead in designing what would become the Crystal Cathedral (fig. 1.4). Schuller’s decision to commission Johnson—founder of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art in 1930 and the leading proponent of the International Style—aroused not a little curiosity in the art world and considerable skepticism from his evangelical counterparts.36 But on September 14, 1980, Schuller dedicated his completed edifice “To the Glory of Man for the Greater Glory of God.”

There are several ways to assess Schuller’s selection of Johnson, a secular Jew, to build a house of Christian worship in Orange County, California. Perhaps it was Schuller’s penchant for pageantry or even his vanity. Perhaps it was his insight into the worship needs and greater witness of his congregation. No matter how one understands the purpose of this high-culture megachurch collaboration, it demonstrated the ability of an elite secular architect to partner with a high-profile religious leader to respond to the fluid cultural matrix of their day.

In the end, the premise that culture can be understood as something separate from regular life is both untenable and false. No matter what ism or creed one heeds, to the extent that one shares economies, language, symbols and technologies with one’s neighbor, one will find oneself swimming in some region of the same cultural pond. In the end, whatever combination of cultural perspectives one may hold to, the shared space and place that we call “culture” is where we all endure threats and encounter limits, even as we seek sustenance and strive to flourish.

SECULAR OR SACRED

In 2003 reporter Sarah Boxer interviewed painter Hedda Sterne (1910–2011). Ninety-three years old, Sterne recounted a story that she once shared with the celebrated abstract expressionist painter and sculptor Barnett Newman (1905–1970). “A little girl is drawing and her mother asks her ‘What are you drawing?’ And she says, ‘I’m drawing god.’ And the mother says, ‘How can you draw god when you don’t know what he is?’ And she says, ‘That’s why I draw him.’” According to Sterne, Newman liked the story so well that he wanted to adopt it as the motto for abstract expressionism.37

As this exchange between Sterne and Newman confirms, it would be wildly inaccurate to suggest that modernism and its proponents held no interest in metaphysical or spiritual matters.38 To the contrary, artists such as Constantin Brancusi, Paul Klee, Kazimir Malevich, Isamu Noguchi and a host of others were powerfully drawn to spiritual practices and ideas.39 For many, this fascination had been catalyzed by Wassily Kandinsky’s 1911 essay Concerning the Spiritual and Art.40 Kandinsky, whose affiliation with the Blau Reiter group is cited earlier in this chapter, had been trained as a lawyer and was a practicing theosophist. He believed that abstract color and form could express the spiritual nature of being. In this regard, his painting and writing held considerable sway, but none greater that his posthumous influence on abstract expressionism and in particular the work of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko (1903–1970). In this regard, Newman’s Stations of the Cross (1958–1966)—fourteen large paintings on view in the East Building of the National Gallery in Washington, DC—is exemplar. Though a Jew and not a Christian, Newman’s minimalist work employs an austere modernist form to explore the central Christian doctrine of Christ’s passion.

On the heels of Newman’s achievement, patrons John and Dominique de Menil commissioned Mark Rothko to create work for the interfaith de Menil Chapel in Houston (1971). Rothko’s paintings—also fourteen in number—would become his most important achievement.41 By design, Rothko’s color fields were luminous and ethereal. Since the work contained no symbols or images, the artist’s intention remained highly enigmatic. Fortunately for us, Rothko’s ample commentary rescues the meaning of his work from obscurity and poignantly so: “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate these basic human emotions. . . . The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience as I had when I painted them.”42 Tragically, Rothko would not witness the final installation of his dark-hued paintings in the de Menil chapel. In the aftermath of a painful divorce from his wife and struggling with failing health, on February 25, 1970, the artist committed suicide. He was sixty-six.

In their quest to probe spiritual reality, other modernists explored the vitality of the Christian story more directly than either Newman or Rothko. Consider, for instance, the tongue-in-cheek work of Andy Warhol, most notably his Last Supper series (1986). The Christian themes in Warhol’s work were hardly happenstance. According to art historian Jane Daggett Dillenberger, the primary source of Warhol’s Catholic devotion was his much-beloved mother, Julia Warhola:

Before leaving home each day, Andy knelt and said prayers with her [Julia], in Old Slavonic. Andy wore a cross on a chain around his neck under his shirt and carried a pocket missal and rosary with him. His mother kept crucifixes in the bedroom and kitchen, and she went to services regularly at St. Mary’s Catholic Church of the Byzantine Rite. In Julia’s yellowed and frayed Old Slavonic prayer book there is a commemorative card with a cheap reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper which Andy must have seen. This is a sentimentalized version of Leonardo’s masterpiece, which Warhol recreated, using other copies of the original, in over a hundred paintings and drawings in the last years of his life.43

Consistent with his earlier practices, Warhol created his Last Supper by reproducing and then altering images from Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, a mural painted by the fifteenth-century artist in the chapel of the Church of Santa Maria della Grazie. In due course, Warhol’s appropriation of this sacred art and the biblical story that it contained was exhibited at Credito Valtellinese, a bank in Milan located directly across the street from the Santa Maria della Grazie. There is a sense in which the initial exhibit of Warhol’s facsimiles in a secular space juxtaposed to the sacred sanctuary that housed da Vinci’s original painting mirrored his troubled relationship to Catholicism.44 It is claimed, for instance, that while Warhol attended daily Mass with some regularity throughout his life, he refrained from partaking of the Eucharist. The Last Supper series was Warhol’s final major work before his untimely death in 1987. He was fifty-eight.

Whether allusion, art historical trope or ironic treatment, Warhol’s appropriation of da Vinci’s Last Supper, as well as the countless riffs on this theme by other artists throughout the modern and contemporary periods, demonstrates the resilience of the biblical story in the history of Western art.45 Indeed, from Antoni Gaudí’s (1852–1926) Expiatory Church of the Holy Family, a monumental Roman Catholic Basilica in Barcelona, to Georges Rouault’s (1871–1958) Misère series depicting the sufferings of Christ, to Marc Chagall’s (1887–1985) biblical narratives in prints and stained glass, the imprint and gravity of the Christian narrative endured throughout the twentieth century.46

In their day, few evangelicals would have been aware of seminal artists like Newman, Rothko and Warhol. For the most part, the spiritual interests of these painters existed quite apart from formalized religion and especially Christian dogma. Rather, modernist fascination with the spiritual gravitated to the numinous and the liminal—matters of soul, states of consciousness and approaches to the Absolute that found their source in modern psychology, literature, philosophy and, not infrequently, non-Western religion. The overarching desire of these twentieth-century artists, writers and philosophers was to locate some evidence of existential meaning and, with that goal before them, they sought sublime aesthetic encounters.

Ironically perhaps, the imprint of traditional religious practice was not easy for modernists to shed. In pursuit of the spiritual, more than a few likened their studio practice to priestly labor: their material acts of making turned to ritual, and their aesthetic experiences became revelation. According to Alain de Botton, the museum itself would become a secular house of worship:

Like churches, they are also the institutions to which the wealthy most readily donate their surplus capital—in the hope of cleansing themselves of whatever sins they may have racked up in the course of accumulating it. Moreover, time spent in museums seems to confer some of the same psychological benefits as attendance at church services; we experience comparable feelings of communing with something greater than ourselves and of being separated from the compromised and profane world beyond.47

And, as Sarah Thornton explains, this questing continues: “For many art world insiders and aficionados of other kinds, concept-driven art is a kind of existential channel through which they bring meaning to their lives. It demands leaps of faith, but it rewards the believer with a sense of consequence.”48 As conscious beings, the meaning question will not go away; it dogs us.

To professing, Bible-believing Christians, the kind of secular spirituality outlined in the previous paragraphs will seem mostly misguided and far afield from any kind of saving faith. Historically, Christians have generally equated spirituality with ways of being that are practiced by those seeking to follow God and the spiritual, that transcendent realm where God exists. According to this view, neither spirituality nor the spiritual finds its source in human understanding, since these realities cannot be summoned from within. Rather, knowledge about God comes to men and women as revelation, first as the book of creation and second as the book of Scripture. Just as creation—the works of God—bears witness to God’s invisible power and eternal nature, Holy Scripture—the Word of God—tells of his true nature and being.

Early in the twentieth century and fearing admixtures of Protestant liberalism, religious syncretism and secular unbelief, conservative Protestants sought to protect their doctrine of revelation and to that end waged a “battle for the Bible.”49 The outcomes of this century-long effort to defend the Bible were various. In some instances this impassioned effort galvanized disparate factions in the conservative movement. On other occasions it fostered intense parochial disagreement and dissent. Pertinent to the concerns of this book, the crusade for biblical truth inflicted collateral damage on those who entertained other genuine ways of knowing—knowledge born of narrative, symbol, mystery and haptic experience—ways held by the majority of artists in the church.

As noted, some modernists maintained a keen interest in the spiritual, but this fact notwithstanding, the general direction of the movement is best characterized as a centuries-long migration from an earlier vision that had once been nurtured and then groomed by a life-giving connection to Christian theology to one that found its primary inspiration in secular thought. The sources of this roiling intellectual revolution were seminal figures including Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, Karl Jung and Friedrich Nietzsche—men with capacious minds who were eager both to capture the spirit of their age, its Zeitgeist, and to diminish or obliterate Christian beliefs and especially the institutions that housed them. With that goal before them, they recast their respective disciplines—economics, the natural sciences, psychology and philosophy—in nontheistic forms that would directly challenge Christendom, the grand narrative of the West.50 If some in the nineteenth century had begun to entertain agnosticism, the twentieth-century rush toward atheism was swift and bold. Roger Lundin explains it like this:

We have learned to live with unbelief in our midst and, in many cases, our hearts. Yet when it first broke upon the scene in the mid-nineteenth century, a sense of disruption and disorientation was palpable, even overwhelming for some, as within a matter of decades unbelief went from being an isolated experience on the cultural margins to becoming a central facet of modern life.51

To illustrate this dramatic shift, consider the atheism espoused by esteemed British mathematician and political activist Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) in his pamphlet Why I Am Not a Christian (1927). In the late 1920s, Russell’s pronouncements may have seemed either scandalous or brave. But on entering the twenty-first century, views such as Russell’s appear commonplace and, with that, any popular worry about one’s eternal destiny became a hopelessly antique concern.

While it is beyond the scope of this book to give either agnosticism or atheism its serious due, it is not difficult to understand the modern collapse of confidence in God’s providence. In light of the human carnage of trench warfare in World War I, the Nazi genocide of six million Jews and other ethnic minorities in World War II, and America’s eventual and pointless war in Vietnam, there was ample cause for despair. If human progress—especially the marvels of science and technology—was an understandable occasion to display a bit of twentieth-century hubris, the horrors loosed on humanity by its inventions were unspeakable. The long shadow of modern violence and savagery compelled many to ask, “If God is powerful and compassionate, then why did he allow this?” And under these circumstances more than a few artists were left to wonder what justification there could be for continuing to make art.52 These penetrating questions remain, and, in my view, the most fitting first response before them is silence.

By mid-century the footings for the modernist scaffolding had been poured deep into disenchanted ground. In the face of Cold War moralizing and rigidity, a new retinue of artists, critics, galleries and museums would parade aesthetic anarchy. And as old deities and weary traditions were exorcised, daily studio practice, high-minded theorizing and the art market rose up to occupy the vacancy. Sufficient unto itself, the art world came of age, and its fraternity of bohemian artists, aesthetes and collectors could herald the movement’s final triumph: l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake).53

Thus far in this chapter we have examined the contrasting postwar approach of the art world and the evangelical church first to culture and then, in this section, to religious belief. To the secular mind, the abiding gnosticism, piety and fundamentalism of evangelicalism—its failure to meaningfully engage immanence, groundedness and freedom—placed it dramatically out of touch with the interests of contemporary artists, who saw no tangible relation between the aesthetic pleasures and freedoms they sought and the church’s long-standing commitment to revelation, authority and fidelity. Consequently, artists who came of age in the 1960s and beyond found it difficult—even impossible—to see any virtue in an earlier conception of the world wherein the biblical narrative guided art in the West, Christian symbols and metaphors prospered, and stories of simple faith announced the sacred character of ordinary life.

Without question, modernism was a secular project. Nonetheless, some of the movement’s leading artists were animated by a fascination with the metaphysical and the spiritual. Christians who are keen cultural observers might take encouragement from this report. But alas, the intellectual pitch of America’s elite art museums, galleries and academies, in partnership with the publishing houses and academic departments that supported them, remained hostile to traditional Christianity.54 In this regard the exoticism of such things as Zen Buddhism, shaman rituals, Islamic art and Jewish art were welcome. In rare moments the academic study of Christian themes was tolerated. But in secular academic and cultural centers, “heartfelt” orthodox Christian belief was considered quaint, naive and irrelevant.

AESTHETES OR DISCIPLES

Though it may seem altogether strange, in postwar America the evangelical church and the modern art movement did share one patch of common ground: an all-consuming desire to effect personal and cultural transformation. That is, the leaders of both movements were unabashed zealots, eager proselytizers. If conservative Protestants labored to disciple a generation of godly people to evangelize the globe, then the art world schooled young aesthetes to embark on a daunting material and ideational struggle. Put differently, even as many evangelicals longed to return America to the narrow path of biblical truth and traditional mores, the art world campaigned for artistic freedom and advanced a new, radical understanding of the self. Each was, in its way, hardwired to be a witnessing presence.

The modernist movement was promulgated by avant-garde artists in leading cultural centers like Barcelona, London, Paris and Zurich in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From its inception, modernism—and its disruptive submovements cubism, Dada, expressionism, fauvism, futurism, impressionism, surrealism, to mention a few—was marked by its pursuit of new plastic forms and utopian ideals, and these were frequently enumerated in edgy manifestoes. Predictably, public reaction to these avant-garde ventures was usually shock or outrage. But almost without exception, these early provocations went on to gain critical, institutional and even popular support, and with this the artist’s role as modern prophet and muse grew in scope.

Following World War I and well into the postwar period, European artists found safe harbor in New York: a metropolis soon to become the hub of the international art scene.55 A striking emblem of this historic recentering is an image that first appeared on the January 15, 1951, cover of Life magazine (fig. 1.5). It features a group of New York artists who, because of their protest against the exhibition policies of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1950, had come to be known as the Irascibles. This artist collective included abstract expressionist painters such as Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, who, in partnership with other luminaries such as Hans Hoffman and Arshile Gorky, would form the center of what came to be known as the New York School. Notably, three of the fifteen were émigrés, and at least three more were first-generation sons of émigrés. Only one, Hedda Sterne (noted earlier), was a woman. Many of these artists lived in cold-water flats, surviving on whatever odd jobs they could find. A favorite watering hole was the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village, where they fraternized with Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Frank O’Hara. Known to us now as the icons of American modernism, most of these painters and writers went on to enjoy celebrated careers. But none, not even Rothko, would rise as high as Jackson Pollock (1912–1956).

Born in Wyoming and the son of a shiftless sheep rancher, Pollock’s persona was perfectly suited to the swagger and machismo of American culture. Pollock’s America—a nation that would spare no expense to place the first man on the moon—was a nearly ideal environment in which to launch unfettered aesthetic exploration. While studying at the Art Students League in New York City, Pollock met Thomas Hart Benton.56 Benton, known to be “a virulent, truculent, hard-drinking macho-man,” quickly became Jackson’s mentor.57 Although the young painter rejected his mentor’s realist aesthetic, Pollock’s temperament resembled Benton’s, and by age twenty-five Pollock was being treated for alcoholism. Two years later he entered into Jungian psychoanalysis.

Early in his career, Pollock was fascinated by mythopoetic symbols, likely a debt to his clinical exposure to Carl Jung. But the mainstay of his oeuvre quickly became “drip” or “action” paintings—expansive works such as Autumn Rhythm (No. 3), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, or Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) (fig. 1.6), in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. To some viewers, these large canvases suggest everything from complex neural networks to rapidly expanding cosmic dioramas. Viewed in this manner, they invite visceral engagement. To others, Pollock’s marks appear to be nothing more than drizzled paint. While Pollock’s mature work may now seem de rigueur, in its day it was provocative and without precedent and since the late 1950s has occupied an exalted place in the modernist canon.

If any artist in the postwar period personified the conviction that art is primarily an expression of the self, surely it was Pollock. Describing his creative practice, Pollock once volunteered, “The thing that interests me is that today painters do not have to go to a subject matter outside of themselves. Most modern painters work from a different source. They work from within.”58 Painter Lee Krasner, the artist’s wife, recounts the time that she brought the celebrated color field painter Hans Hofmann to visit Jackson. Hoffman queried, “Do you work from nature?” Pollock famously replied, “I am nature.”59

On first impression, Pollock’s declaration might appear entirely romantic. That is, summoned by the grandiosity of nature and quickened by the special ability of artists to divine spiritual meaning from it, proponents of romanticism regarded their efforts as a counterproposal to rationalism. Romantic poets, musicians and painters believed that their collective enthrallment could challenge the burgeoning optimism of the Enlightenment and its confidence in the ability of science to define, manage and improve the world. Simply put, if science had disenchanted the universe, art could restore it.

Unwittingly perhaps, Pollock and his ilk had taken their cue from Nietzsche, who claimed, “Nature, artistically considered, is no model. It exaggerates, it distorts, it leaves gaps. Nature is chance.”60 The ascendancy of Darwinian thought had demystified the natural world, displacing earlier celebrations of creation as the shining evidence of God’s handiwork with cooler conceptions of nature as randomly generated evolutionary effects. But matters would evolve (or devolve) even further. As Lundin points out, “By the end of the eighteenth century” romantically inclined artists and intellectuals “were crying out for a world that could match in its external splendor the marvels created by the imagination in its internal wonder.”61 If a Spirit-hosted universe did not exist, then the numinous and the transcendent would need to be born afresh by the creative powers of the artist. From this point forward, the flame igniting artistic passion could be lit only from within.

Pollock was an immense talent. His Promethean drive, coupled with the expressive freedom and critical endorsement of the New York scene, contributed to the artist’s meteoric rise in the art world. But Jackson was also a troubled, demon-haunted soul. Drunk behind the wheel and with his mistress Ruth Kligman at his side, he met his end in a fatal car crash. Pollock was forty-four. Kligman survived.

As Pollock’s rise and demise suggests, the ascent of modernism signaled an extravagant new estimation of the self—a contemporary “self-consciousness” that would go on to form the basis of nearly every conception of personal identity. This emerging notion of the self was rooted in the older Renaissance conviction that humanity is the measure of all things. Indeed, the Renaissance was enamored of the possibility of human genius, an idea that, though much debated, persists in all the arts through to our present day.62 But even this understanding of the self—informed substantially by the Enlightenment—would be cast aside by modern philosophy and the rising social sciences.

The modernists found themselves in opposition to their world for reasons which were continuous with those of the Romantics. The world seen just as mechanism, as a field for instrumental reason, seemed to the latter shallow and debased. By the twentieth century the encroachments of instrumental reason were incomparably greater, and we find the modernist writers and artists in protest against a world dominated by technology, standardization, the decay of community, mass society, and vulgarization.63

As well as any, the words of Barnett Newman capture the moment: “We are freeing ourselves of the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, myth or what have you, that have been the devices of Western European painting. Instead of making cathedrals out of Christ, man, or ‘life,’ we are making [them] out of ourselves, out of our own feelings.”64

The art world’s dynamic migration toward individual expressive freedom underscores the true nature of the aesthetic revolution that had unfolded. These ascending notions of intellectual, moral and aesthetic emancipation were bolstered by everything from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself (1855) in the nineteenth century to Jack Kerouac’s stream-of-consciousness epistle On the Road (1957) in the twentieth.65 And it was on this frontier of new freedoms that artists staked their claim. To the secular mind, genuine personal emancipation would release the human spirit from religious superstitions and oppressive hierarchies, and the idea of “self-determination”—a virtue principally linked to nation building and international diplomacy—came to form the basis of a new and radical individual autonomy.

The desire for personal emancipation is a thoroughly American ideal and the foundation of religious liberty itself. Indeed, the nation was settled by immigrants seeking release from the authority of the church and the crown. Conservatives and liberals would be allied in the commitment to the virtue and exercise of personal freedom. But this shared commitment then leads us to observe that the postwar conflict surrounding freedom was not about its possibility but rather its essential nature, and at this point a great divide opens.

For artists at least, this new, radical freedom was bent on dismantling tradition in at least three forms.66 First, it rejected conventional creeds, confessions and polity—any tangible connection of art to traditional Christian doctrine and practice. Second, it abandoned academic art—classical ideals such as proportion, symmetry, harmony and beauty derived primarily from the study of the human figure. Third, artists paired their new aesthetic freedom with moral license, throwing off any constraint—be it from the church or within the academy or the larger culture—that might abate pleasure. In effect, Rothko, Pollock and others had embraced the Nietzschean project “to replace Christian morality with a secular ideology revolving around philosophy, music, and art.”67

But in vanquishing tradition, dispatching legitimate authority and removing personal boundaries, communal norms essential to daily life would also be swept away. In the aftermath of modernism’s heyday, America’s Christian manners and mores would be forever altered as the nation uncritically embraced what Christopher Lasch termed “the culture of narcissism.”68

Meanwhile, artists and other cultural elites imagined that all “born-again,” “Bible-believing” Christians belonged to the fundamentalist tribe.69 For these elites, Christian fundamentalism could be understood only as the antithesis to artistic freedom. In response, conservative Protestants seldom advanced an equally robust biblical understanding of freedom. They understood freedom first and foremost as liberation from sin and the subsequent physical and spiritual death that sin proffered. It was freedom from the tyranny of evil and freedom to be ones who bear the image of God. In fact, this kind of teaching was present even in the most conservative settings, but it was often eclipsed or negated by legalism. More generous, though sometimes controversial, meditations on the meaning of grace would come later.70

Patterns of advance and retreat are native to all cultural change. Although the New York School functioned as a loose affiliation, and its members—such as Gertrude Stein’s Parisian Salon (c. 1905–), the Bloomsbury Group (c. 1905–1932) in Britain, the German Bauhaus (1919–1933) and Black Mountain College (1933–1956) in North Carolina—were modest in number, its measure of cultural influence outpaced the wildest imaginings of its founders.71 It was humble yet visionary beginnings such as these, alongside others in Chicago and on the West Coast, that spawned a vibrant network of art schools and departments, galleries and museums. From the 1960s onward the modernist aesthetic gradually secured its place as the core curriculum of nearly every secular art department in America and, for that matter, most church-related colleges and universities.72 At its zenith modernism impacted every corner of the art world, even the more traditional academies that railed against it. Aided by the powerful engine of commerce, this new aesthetic captured mainstream America and found expression in a raft of cultural goods, including popular music, cinema, design, fashion and architecture.

But modernism would pay a steep price for its success. As historian Stuart D. Hobbs observes, by the end of the century postwar intellectuals actually rejected bohemianism: the “cultural outsiders became insiders.”73 In the closing decades of the twentieth century, it seemed that Rothko’s, Warhol’s and Pollock’s bold acts—their canvasses—would surface most often as mere illustrations ornamenting the covers of psychology and philosophy textbooks. Leeched of its vitality, the “shock of the new” had been domesticated.

Modernism’s move inside, its general acceptance in American life and culture, hardly signaled an end to avant-garde thought and practice. To the contrary, the radical freedoms gained early in the postwar period would be repositioned in the 1980s to express postmodern acts of aesthetic, social and political transgression.74 And it was from this point forward that any popular or critical resistance to this advance would be branded “intolerant.”

This introductory chapter has attempted to cover considerable ground. To set the table for the chapters to follow, a fitting summary might be this: if, during the postwar years, modernists struggled to make sense of the artist’s role with respect to tradition, the elusive quest for meaning and the necessary freedoms to pursue both, evangelicals found their focus in defending biblical truth, upholding personal piety and advancing the gospel.

Sadly, while many of us have gained a clearer picture of art and faith in American life and culture in the latter half of the twentieth century, this does not diminish the profound sense of alienation that was experienced by a modest cadre of Christians in the visual arts during those decades. In their day, they faced a pair of sad alternatives: either privatizing their religious identity in the art world or producing sentimentalized art for the church. In other words, assuming a dual identity was the only way that these artists could secure a foothold in both communities. It is, quite simply, the kind of dilemma that marginalized people face. Here the words of sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), the first African American to earn a PhD from Harvard University, are most fitting: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”75 To be both a practicing Christian and a practicing artist seemed not to be a legitimate option.

Having reached the end of this chapter, one could easily imagine that the movements we have examined were self-contained, monolithic subcultures fundamentally opposed to each other. To many political pundits and social observers, this apparent conflict between the art world and the church was a kind of perfect storm. Indeed, those hoping for this to be true will find no shortage of anecdotal evidence. But apart from rabid and polarizing media attention, it was less hostility and more ambivalence that characterized the relationship. That is, during America’s postwar period, artists and evangelicals behaved less like contestants slugging it out in the ring and more like ships passing in the night.