2

The Body They May Kill

The body is the emblem of our common humanity.

’Twas much that man was made like God long before;

But that God should be made like man, much more.

The human body was made to be the vehicle of human personality ruling the earth for God and through his power. Withdrawn from that function by the loss of its connection with God, the body is caught in the inevitable state of corruption in which we find it now.

In his 1972 novel My Name Is Asher Lev, Chaim Potok introduces readers to a simmering conflict that is soon to boil over between a prodigy named Asher and his pious Jewish parents and their Hasidic community. While Asher’s parents, especially his mother, possess deep affection for him, Potok’s readers quickly learn that the boy’s aesthetic vision does not comport with his family’s traditional values. As Asher’s passion for art rises, so also does his alienation from those whom he loves, and in due course his body and spirit are marked by anxious struggle.

Midway through the novel, the young painter meets Jacob Kahn—a seasoned artist and a secular Jew—who introduces sheltered Asher to the Museum of Modern Art, the nude and even Christian iconography. As Kahn begins to mentor Asher, he urges him to draw directly from the model:

The human body is a glory of structure and form. When an artist draws or paints or sculpts it, he is a battleground between intelligence and emotion, between his rational side and his sensual side. You do understand that. Yes. I see you do. The manner in which certain artists have resolved that battle has created some of the greatest masterpieces of art. You must learn to understand the battle.1

Asher embraces Kahn’s challenge, understanding that this decision to paint the nude and, eventually, the body of Christ will fully and finally estrange him from his Orthodox community. Nearly released from the burden of his conservative upbringing and with the prospect of an artist’s life before him, Asher is confronted by his father, who makes one final plea: “Do not forget your people, Asher. That is all I ask of you, that is all that is left for me to ask you.”2

In the third section of Potok’s novel, Asher travels to Florence, where he, like many before him, is deeply moved by Michelangelo’s towering David and the sculptor’s more tender Pietà. Asher’s encounter with these marble carvings stimulates a new body of work, including two large paintings that his dealer, Anna Schaeffer, titles Brooklyn Crucifix I and Brooklyn Crucifix II. Schaeffer proceeds to exhibit Asher’s new work in her New York gallery, and reviews of the same are published in the New York Times, Time and Newsweek. To the horror of his now-estranged community, this critical attention includes photographs not only of the paintings but also of Asher and his parents. The family’s unsolicited association with Asher’s Christian imagery, now on public view in the secular art world, is seemingly an unforgivable offense.

The final episode in Potok’s novel features yet another conversation, this time between Asher and a distraught rabbi who has failed to persuade the artist to attend a yeshiva in Paris. The teacher laments, “You have crossed a boundary. I cannot help you. You are alone now, I give you my blessings.”3 The artist’s decision to paint and draw the nude is especially problematic. In the end, Asher’s religious community—once a source of spiritual succor, an island of certainty in an uncertain world—is neither able nor willing to nurture his creative vision.

In reading the novel, many artists hailing from evangelical and fundamentalist Christian communities find that Potok’s coming-of-age account dramatically parallels their own. Like Asher, their pursuit of the visual arts has required them to reassess familial and ecclesial obligations, the attendant costs and benefits of entering the secular art world, and the relative merits of painting and drawing the nude. Most Christian students drawn to the arts either have or will sort through these challenges in a college or university art department.

It is not uncommon for faculty, administrators and trustees at church-related colleges and universities to engage in long and vexing debates over the prospect of students drawing unclothed models in the schools’ art studios and the exhibition of the same in their galleries. For art faculty on these campuses, the failure to provide a meaningful figure study program is thought to be substandard. Meanwhile, efforts to offer these courses invariably summon powerful and competing concerns, not least the fiduciary interests of the institution’s board of directors, the piety of its undergraduates and the secular training of the school’s art department faculty. If these parties manage to find common ground, it is usually the fruit of considerable compromise. But when agreement cannot be reached, this unsettled business often stirs up ongoing discord between faculty and administrators, which in turn negatively affects art department instruction and morale.

The battle at church-related institutions surrounding the human body and its representation is just one telling of a larger story. Many Christian undergraduates also pursue fine-art programs at secular schools or academies where degree plans routinely require at least one course in drawing or painting the nude. I suspect that many, in the face of the challenge of this standard obligation, have or will have an experience similar to mine.

On entering my first figure-drawing session, the sexual undertone and related vulnerability of our disrobed model was undeniable, and my awareness of this lingered throughout the semester. But it quickly became apparent that the actual practice of drawing the nude figure bore no tangible relationship to the tawdry world of pornography or, for that matter, the salacious sex scenes offered up in contemporary cinema. Moving beyond my initial apprehension, it took no more than one or two class sessions to recognize the greater challenge of this discipline: just as our model struggled through stiffness and discomfort to maintain the pose assigned to him, I too, perched at one of the drawing boards circled about the room, would need to face the steep demand of these ninety-minute sessions. In fact, rendering the human form requires exceptional hand-to-eye coordination and careful attention to the nuances of the male and female form, differences most novices fail to perceive. If I hoped to realize any success, it would require all that my mind and hand could summon.

As the months passed, a further realization settled in: having submitted myself to the rigors of drawing the nude, I was apprenticing myself to an enduring classical tradition. Like the bodies of the student artists, the bodies of our male and female models bore fingers and forearms, abdomens and breasts, calves, ankles and buttocks. To study the live model is to observe her or his body as she or he breathes in and then out, to notice the pattern of light as it casts shadow shapes across her or his form. In fact, we had been granted permission to study an embodied spirit, the beauty and the poetry of the human form coupled with its unwanted blemishes, awkwardness and even pain. In other words, during my undergraduate studies any awkward feelings I may have had about the discipline of figure drawing gave me only slight pause when compared to the demands of the task itself.

What I found more troubling was the obligation that I sensed to persuade the Christian community that my classroom obligation to draw the nude was not a wholesale capitulation to worldliness. But my apologetic, slim and unpersuasive as it was, fell mostly on deaf ears, even to some in the campus fellowship to which I belonged.

Having recounted Asher Lev’s decision to pursue his artistic vision and my first experience drawing the figure, I should mention one concern before pressing on to the larger topic at hand. From time to time students, usually from more conservative religious backgrounds, feel compelled by conscience or conviction to ask their art department (whether at a secular institution or a church-related school) to waive its figure drawing requirement. In an age of rampant sexual abuse and exploitation, it seems prudent to agree that drawing, painting or sculpting the nude might pose, for some, a moral, psychological or spiritual dilemma. Since it is impossible to know the inner workings of another person’s mind or heart, I believe that any student who requests an exemption should be excused from the rigors of this discipline and without stigma or retribution. At the same time, just as the study of anatomy and physiology in a nursing or premed program is a standard requirement, it is my conviction that every art major should be expected to successfully complete at least one or more courses in drawing or painting the figure.

Depicting the body, with its much-vaunted significance in the visual arts and the controversy that accompanies it, is the central concern of this chapter. For many Christians the study of the nude human form represents highly contested territory, and the reason for this seems straightforward: in American life and culture the presence of an unclothed male or female body is freighted with sexual baggage. For many Christians this matter is further complicated by the tendency of so many to adopt a gnostic spirituality wherein Christian life, in its most elevated state, is not only thought to be unhinged from material reality, but goes further to deny the reality of embodiment. Since the purpose of this book is to make some sense of the relationship—or lack thereof—between the evangelical church and the art world during America’s postwar period, it is crucial to sort out the nature and meaning of our physical bodies with respect to the visual arts and Christian discipleship.

IDEAL FORM

From culture to culture and epoch to epoch, the manner in which the clothed and unclothed body has been treated in the visual arts varies dramatically. In most Western countries, it is the classical Greek tradition and its powerful reappearance during the Italian Renaissance that forms the basis of modern and contemporary understanding of the body. In the opening pages of The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, Sir Kenneth Clark delineates the difference between nudity and nakedness:

To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition. The word “nude,” on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone. The vague image it projects into the mind is not of a huddled and defenseless body, but of a balanced, prosperous and confident body; the body re-formed.4

Clark goes on to explain that the depiction of the nude in Western art originated in ancient Greece (c. 500 BC), where the beauty of the perfected body was celebrated. In the Greco-Roman world, the body in its ideal form was often expressed in mathematical formulae, and the resulting ratios became the basis for everything from the design of columns, doorways and temples to a means to comprehend the divine.5 “The Greeks perfected the nude in order that man might feel like a god, and in a sense this is still its function, for although we no longer suppose that God is like a beautiful man, we still feel close to divinity in those flashes of self-identification when, through our own bodies, we seem to be aware of a universal order.”6 Indeed, the actual measure of the human body is our basis for determining the intimacy that we sense while seated in a neighborhood café or, conversely, the monumentality that overcomes us in the grand space of a Gothic cathedral. Our corporeal being locates and then grounds us in space and time, and apart from this we would truly be lost in the cosmos.7

In the early church, representations of the body, especially images of gods and goddesses, were associated with pagan practices. In the centuries that followed, similar depictions of the Christian Godhead were created to cultivate profound theological and spiritual truths.8 But at the zenith of medieval asceticism, realistic renderings of the nude faded almost entirely from view. And it was generally the case that steady Christianization of the West signaled the decline of the figurative tradition. However, a notable exception to this pattern emerged. As art historian Timothy Verdon points out, “It was in Italy and by the end of the twelfth and the middle of the thirteenth centuries, that a dramatic and—for the West—decisive process of change began. Art rediscovered the body in fully religious terms, as a privileged vehicle of spiritual experience, the locus of a uniquely Christian sanctity.”9 For two centuries or more, the Italian Renaissance stimulated an unprecedented revival of the nude, and to that end the church and the art world found common cause. Marsilio Ficino, a leading humanist in fifteenth-century Florence, “taught that the human figure occupied a central position between heaven and earth. By turning toward earthly love, one could descend to the lower state, or by turning in love toward God, one could ascend to his likeness. The body, therefore, was central—it could lead one toward or away from God.”10 Stimulated by the resurgence of Greek thought and the flourishing of humanist studies, the nudes rendered during the Italian Renaissance reached unprecedented levels of verisimilitude at the hand of celebrated artists such as Michelangelo, da Vinci, Bellini, Botticelli and Caravaggio. Suffice it to say, in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italy, the classical ideal of humanity as a demigod regained its public standing.

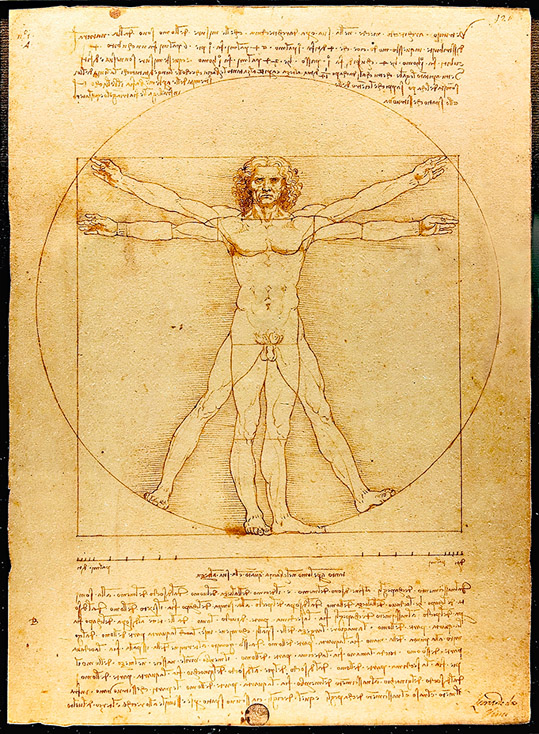

In due course, papal policies grew more austere, and eventually new commissions featuring nude figures or pagan themes, as well as the installation of these works in religious spaces, were forbidden.11 But as church interest in this endeavor grew tepid and cautious, in the art world the function and meaning of the unclothed human form continued to be a central concern. Consequently, in survey classes devoted to Western art, students are likely to encounter everything from Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1487) (fig. 2.1)—wherein an idealized male form is placed within the pure geometry of a circle and a square—to the mythology of Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c. 1484), and from the politics of Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1831) to the impudence of Francisco Goya’s Naked Maja (1797–1800).

A mindful consideration of the figurative tradition reveals something further: study of the nude was hardly limited to the narrower interests of aesthetics and religion. For many centuries this discipline was allied with science so that the line separating the forensic from the aesthetic or the clinical from the visual was hardly visible. Artists were often among the first to examine human musculature and skeletal systems, internal organs, the development of the fetus in the womb and so on. Consider, for instance, da Vinci’s numerous anatomical studies and paintings by Rembrandt such as The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Nicolaes Tulp (1632) and The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Joan Deyman (1658). In the twentieth century, Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) continued this practice in works like The Gross Clinic (1875) and The Agnew Clinic (1889).12

In fact, the Western figurative tradition is neither staid nor secure, and the record of its mercurial rising and falling is well documented. Since the account of artists who painted and sculpted the figure from the mid-nineteenth century onward is decidedly nonlinear, to locate the significance of the human figure squarely within the postwar period, it will be useful to examine five thematic arenas of concern: the radical reappraisal of social and sexual manners, the angst of existential being in the modern world, a critique of popular consumer culture, the politics of difference and, finally, the brokenness of the modern body.

MODERNISM’S BODY

Much of Kiki Smith’s (b. 1954) artistic output has been given to depict bodily forms, especially their transient beauty and provisional nature.13 In this regard, her mid-career sculpture Untitled (1987–1990) is particularly arresting (fig. 2.2). The work consists of a dozen silvered water jars, measuring twenty and a half inches high and aligned single file on a waist-high white base. Etched into the glass of each of the twelve containers is the name of a bodily fluid that is presumably contained within, and the names appear as follows: diarrhea, blood, semen, vomit, tears, pus, urine, saliva, sweat, mucus, milk and oil. Not unlike some medieval scientific endeavor, Smith’s work reduces the body to its constituent fluids. Her seemingly clinical treatment of these extractions and distillations reminds those who view the work that the human body is a vessel, the container of one’s being. On one hand, Smith has tidied up the gross mess of our embodiment, and her alignment of silvered jars and their etched labels brandishes a kind of modernist elegance. On the other, her mere listing of these twelve bodily fluids elicits from most a visceral reaction of disgust or repulsion. However one understands the meaning of Smith’s provocative work, it exists in a universe far removed from a workshop in ancient Greece where, say, a gifted stone carver must labor for many months to render an ideally proportioned Venus. Nonetheless, for both Smith and the unnamed Greek artisan, the body remains a worthy subject, not least because the being of every man, woman and child abides in a body. Aesthetically speaking, it might be reasoned that Smith’s lineup of silvered jars is the logical outcome of a century or more of the figurative tradition preceding it.

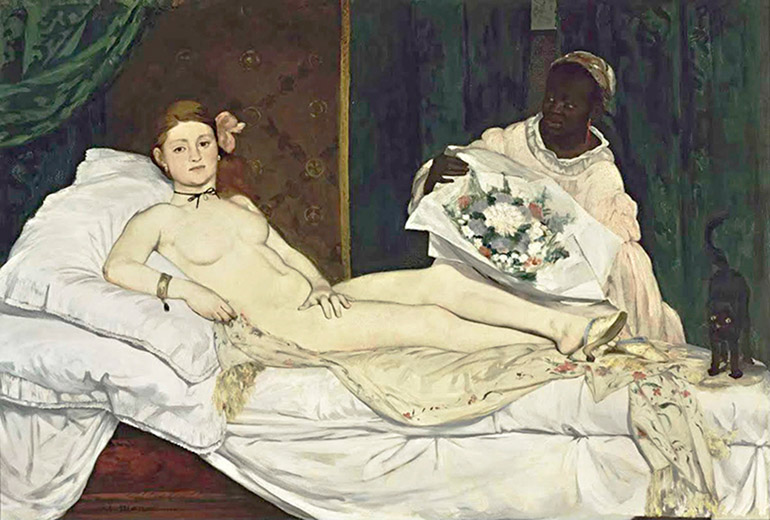

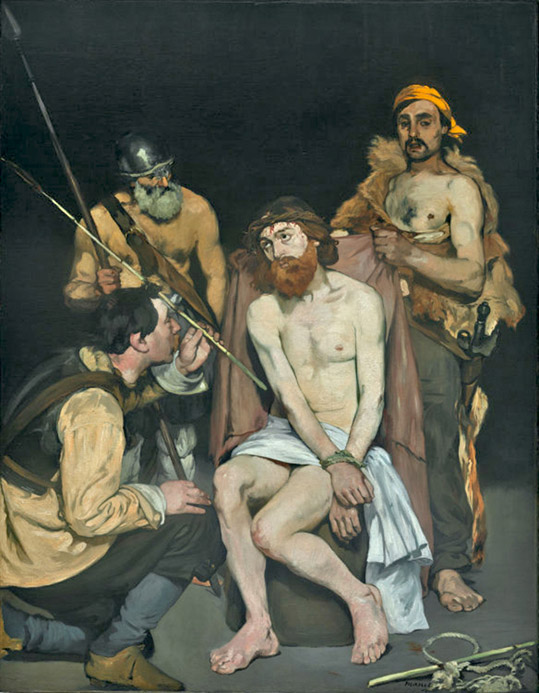

In his book The Painting of Modern Life, art historian T. J. Clark proposes that the first truly modern nude was Édouard Manet’s (1832–1883) Olympia (1863) (fig. 2.3), a painting often compared to Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538).14 Olympia was exhibited in 1856 in the Paris Salon, where it hung beneath another of Manet’s paintings, Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers (1865) (fig. 2.4). While both works explore the stigmatized social standing of their subjects, Manet was painting in a secular city and for a secular age. Therefore, it was Olympia that incited popular derision and critical contempt and not Jesus Mocked by Soldiers.

2.4. Édouard Manet, Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers, 1865

The widespread and negative reaction to Olympia was decidedly not to the model’s nudity, since paintings and sculptures of the nude female figure were commonplace in nineteenth-century Paris. Rather, it was Manet’s bold juxtaposition of Olympia’s likely occupation as a courtesan and her corresponding “uncleanness” over against the symbols of affluence and sensuality that adorned her—pearl earrings and bracelet, a black ribbon about her neck, an orchid in her hair and the oriental shawl beneath—that fomented the outrage. In a forthright manner, Manet’s work showcased the realities of prostitution in Paris and the interchange of class, money and sex that sustained it. Moreover, Manet had not only painted a prostitute; he had depicted a woman who brazenly refused the gaze of those (male clients) who would possess her. “Manet’s [model] is bold and looks directly, almost confrontationally, at the viewer. Thus looking out at those who are looking at her, she defies the age-old objectification of undressed women. And with her candid unidealized appearance, she is a frankly ‘naked’ woman defying a tradition of prettified academic ‘nudes.’”15

To be sure, Manet’s depiction of Olympia’s defiant sexual persona is unhinged or liberated from the constraints of older Victorian and puritanical manners. But more than this, Manet alerts his viewers to the ambiguous social standing of the courtesan. Meanwhile, the black woman, who presumably bears flowers from the courtesan’s client and whose figure occupies a place of importance in the visual structure of the painting, introduces race to the discourse. Manet’s pictorial strategy confirms that whether clothed or unclothed, bodies situated within the picture plane can be used to question the conventions of social class and challenge prevailing sexual mores.

2.5. Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women, 1899

Like Manet, Gustave Klimt (1862–1918) also embraced avant-garde sensibilities and endured hostile reviews from more traditional critics in late nineteenth-century Vienna. But if Manet had managed to explore the social meaning of his courtesan’s world, Klimt was simply enamored of the erotic allure and mystery of the women that he painted. Meanwhile, both Manet and Klimt would have known of Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and his sojourn to Tahiti, where, having abandoned his wife, children and friends, he would spend the final thirteen years of his life. During his stay in Tahiti, the artist frequently painted the female nude, and his work continued to explore quasi-Christian themes (see fig. 2.5). Gauguin was on a quest to find paradise, an Eden apart from the business and infighting of the art world. But, in the end, this effort left him disconsolate.

2.6. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

As demonstrated by their depictions of the female nude, artists such as Manet, Klimt and Gauguin were relocating the central interest of painting away from the verisimilitude and idealism that had guided it for nearly five centuries.16 If the study of the figure once found its primary focus in recounting the stories of nobles, courtiers, prostitutes, revolutionaries, peasants and deities, then from the mid-nineteenth century onward, new social, political and existential understandings of the human form were being cultivated. From this point forward, a common feature of the modern era would be the transformation of what had formerly been private manners to public spectacle. Critically and aesthetically, these kinds of paintings—which relied on a high degree of realistic rendering—anticipated a time when verisimilitude would yield to more plastic, abstract concerns. In 1960, ninety-seven years after Manet had completed Olympia, critic Clement Greenberg anointed Olympia the first truly modernist work and celebrated the “flatness” of its paint.17

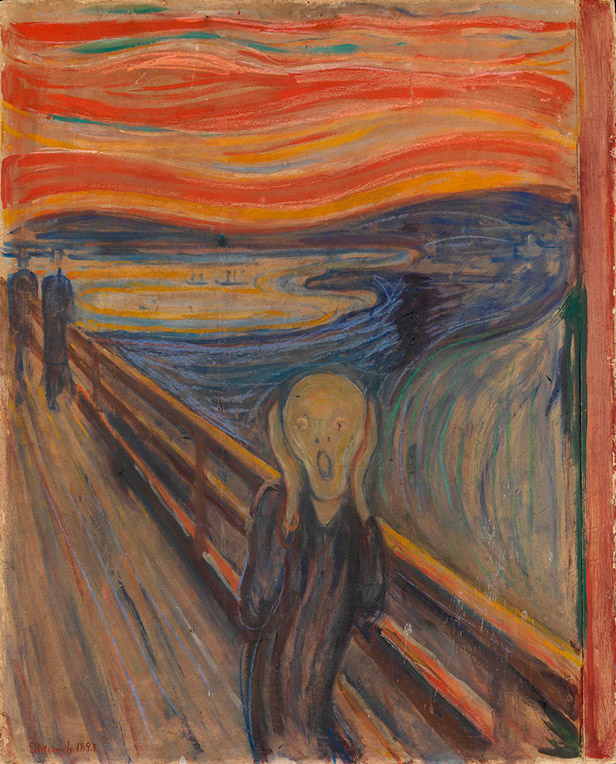

If the coming secular age and its promise of personal and social emancipation seemed intoxicating, this optimism was offset by the horrors of modernity. Like some bewildering Pandora’s box, modern life ushered in the regimens of widespread industrialization, political repression and injustice, the surveillance and brutality of new totalitarian regimes, and, eventually, the unfulfilled promise of consumer capitalism. Despite the seemingly miraculous advances of science and the ever-expanding frontiers of human freedom, the demise of one’s body could not be reversed; death could not be circumvented. It was this modern milieu that sponsored Edvard Munch’s terror-filled painting The Scream (1893) (fig. 2.6), and it was in this same period that Vincent van Gogh produced his garish yet stunning self-portraits. In 1953, sixty years after Munch had painted The Scream, Irish artist Francis Bacon exhibited his Screaming Pope, a work based substantially on the Portrait of Pope Innocent X painted by Spanish artist Diego Velázquez in 1650. Modern artists could not abate the terror of the modern world, and for painters like Bacon the institutional church was complicit in this.

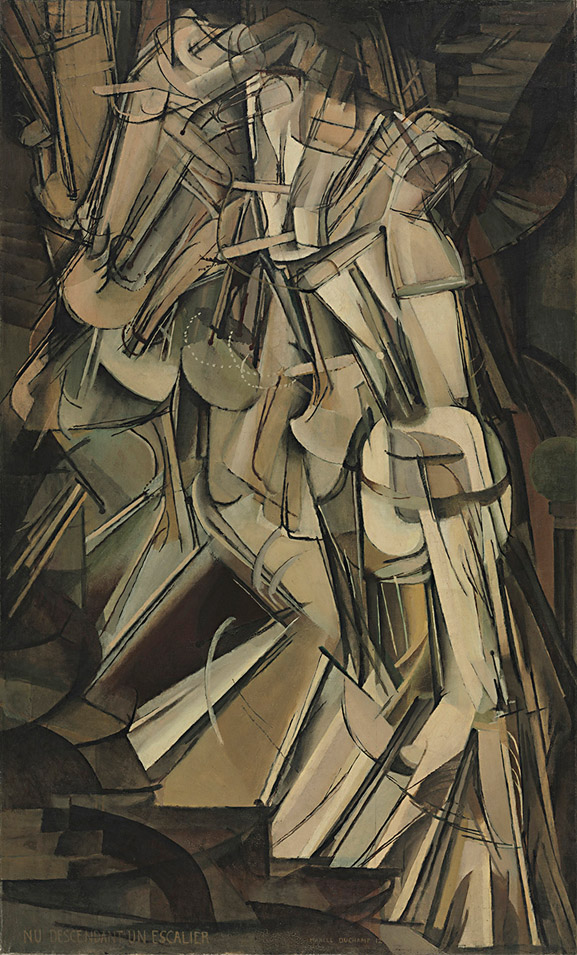

2.7. Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912

Meanwhile, in the twentieth century the cubism of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the deconstruction of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912) (fig. 2.7), the aimless wanderings and alienation of Alberto Giacometti’s solitary sculpted figures and the abstract expressionist canvases of Willem de Kooning’s Woman series charted yet another course for the figure. The severe treatment of these figures, again mostly female nudes, challenged the long-standing assumptions of the figurative tradition: it seemed to these artists that the classic beauty of ideal human forms had been exhausted. Present in their work was an existential anxiety that carried forward the philosophical and literary ruminations of European intellectuals such as Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre. The violence of two world wars, the dismissal of tradition, the ascent of modern psychology and the death of God placed artists and intellectuals alike on the edge of a philosophical precipice. For them, art making was a means to respond to the yawning abyss that opened before them.

By mid-century and especially on the American scene, art turned to explore the weighty business of being a fully modern, social and secular self. With the advent of photography and at the apex of modernism’s aesthetic sway, the realism, verisimilitude and iconography of the past was thought to be horribly out of fashion.18 High modernism was bent on capturing pure form, form unencumbered by the burden of realism and representation. And so, at least for a season, the relative honor or dishonor of the unclothed body would be regarded as a mostly parochial interest. Nevertheless, the figure would remain a perennially important subject, for, as critic Arthur Danto reminds us, “The body is the emblem of our common humanity.”19 And as the earlier reference to Kiki Smith’s silvered jars suggests, this work was often highly provocative, intended to shock the viewer.

THE SEXED BODY

In 1953 Hugh Hefner founded Playboy, the “men’s entertainment magazine.” Hefner’s genius was his ability to exploit and then monetize the precarious tension that exists between nice-girl nudity and its raunchy cousin, pornography. Despised by some and admired by others, Hefner embraced the proposition “sex sells” full on. As early as the 1960s, pop artists such as Mel Ramos (b. 1935) and Tom Wesselmann (b. 1931) played fast and loose with the slippery connection between these kinds of sexually provocative images and their usefulness in gaining market share. Consider the odd dissonance of one Ramos painting, Hippopotamus (1967), in which a curvaceous, blonde female nude awkwardly straddles an enormous, fleshy hippopotamus, or Wesselmann’s Great American Nude series (c. 1961), where campy erotic caricatures of female nudes are surrounded by generic suburban props such as televisions and other household objects. Was the purpose of these works by Ramos and Wesselmann to expose the superficiality of the pinup mythology or simply to exploit it? The answer to this question remains ambiguous. But viewing these works, now decades later, one may be impressed by the pop movement’s ability to mimic and thus critique the emerging social norms of its day.

Was it this same disposition that prompted Jeff Koons (b. 1955) to have his studio meticulously craft Made in Heaven (1989–1991), a series of paintings and sculptures featuring larger-than-life images of the artist with his (now former) wife, Cicciolina (a well-known Italian porn star), in various stages of sexual intercourse? Did Koons create this body of work to seize an art market opportunity? Did he intend to shock his viewing public? Or was this creative venture simply a record of the artist’s narcissism? In the end, the artist would gain considerable critical attention, not least because individual and museum patrons were willing to pay high prices to add a “Koons” to their collection.

My purpose in citing Heffner, Ramos, Wesselmann and Koons is not to celebrate their achievements but instead to point out that beneath the gloss of consumer images and the cultural sophistication of contemporary art, the sinister undertow of sexual exploitation is an ever-present reality. Regrettably, the very freedom that secures space for an artist to produce and exhibit serious work without fear of censure also creates space for a multibillion-dollar porn industry where, under the imprimatur of artistic expression, nearly every instance of critical, cultural and moral resistance is silenced. Once limited to adult movie selections on hotel televisions and the printed page of newsstand tabloids, the ubiquity of internet porn is now considered normative, a cultural given.

The central theme of pornography is male domination over women, other men and even children. As such, it perverts the goodness of human sexuality; worse still, it perpetuates unspeakable evil, enabling as it does the few to amass extraordinary fortunes by materially exploiting the addictions of the many. The dignity of these victims is of no concern to those who profit from them, nor is the degradation of the bodies involved. Ironically and tragically, since neither intimacy nor beauty is here present, sex itself is demeaned. Pornography’s objectification of men, women and children and its chronic sadness are so repugnant that more liberal-minded artists and aesthetes should join with conservatives to condemn it. In the presence of this powerful economic engine—its unequaled capacity to generate and then monetize desire—an undergraduate studying the figure or an artist painting or sculpting a nude in her studio hardly bears mention.

Near the conclusion of Kenneth Clark’s discussion of the nude (cited earlier in this chapter), he compares the work of Henri Matisse to that of Pablo Picasso and then offers this cautionary note: “To scrutinize a naked girl as if she were a loaf of bread or a piece of rustic pottery is surely to exclude one of the human emotions of which a work of art is composed; and, as a matter of history, the Victorian moralists who alleged that painting the nude usually ended in fornication were not far from the mark. In some ways nature can always triumph over art.”20 Like their Victorian forebears, most moral conservatives and, not inconsequently, feminists consider the inevitability of Clark’s scenario repugnant. If moral conservatives remain troubled by the provocative and unending connection between nudity and sexual immorality, feminists rightly protest the objectification of women and their bodies.

In the postwar period, the pursuit of physical beauty could be unrelenting. Reasonable concern for hygiene, fitness and attractiveness often gave way to irrational longings for perfection and, ultimately, immortality. Together, fashion and consumer culture generated ideal images of the male and female beauty managed by the whim and wishes of the market. Countless weight-loss regimens, how-to sex manuals, fitness programs and anti-aging remedies confirmed an American fixation with the body that was tantamount to worship. And this desire for bodily perfection was met by an industry of extreme remedies (surgical, cosmetic, pharmacological and prosthetic) that promised to perfect male and female bodies. With these came a corresponding rise in personal pathologies (eating disorders, drug abuse, self-mutilation and even suicide).21 In the end, the desperate quest for perfection was shaped less by received classical categories of the sort examined earlier in this chapter and more by the demand of fashion. Beneath what could appear to be virtuous pursuits, darker social, sexual, political and economic functions prevailed. What emerged was a highly conflicted understanding of the self with particular regard to the limits and hazards of embodiment, wherein the fact of mortality was both embraced and denied. When bodily perfection cannot be realized, narcissism devolves to tragic forms of self-loathing. Hence the pathos and irony of the bumper sticker that reads “Start a revolution . . . stop hating your body.”22

While the physical beauty of a man or a woman is surely fleeting and the standards used to establish this are superficial at best, popular conceptions of physical beauty remain linked to sexual identity and performance. The history of sexual desire and the corresponding mores and manners assigned to rein it in are vast. In this regard the sexual revolution of the 1960s radically reset the table. Long-standing conventional commitments such as fidelity and fecundity gave way to the promise of heightened and spontaneous erotic sexual encounters to be enjoyed by new emancipated selves.23 A host of emerging realities including free love, feminism and the pill would challenge and, for many, overturn traditional conceptions of marriage. Accompanying the rise of sexual options and preferences was an alarming increase in sexually transmitted disease, interpersonal alienation, sex trafficking and personal brokenness. As general prewar cultural agreements about the meaning of marriage and family dissolved, the decades of lawmaking that followed would secure a new paradigm. The youth culture longed for personal and expressive freedom, and within a decade or so sexual performance and experience would be severed from marital virtues of fidelity and commitment.

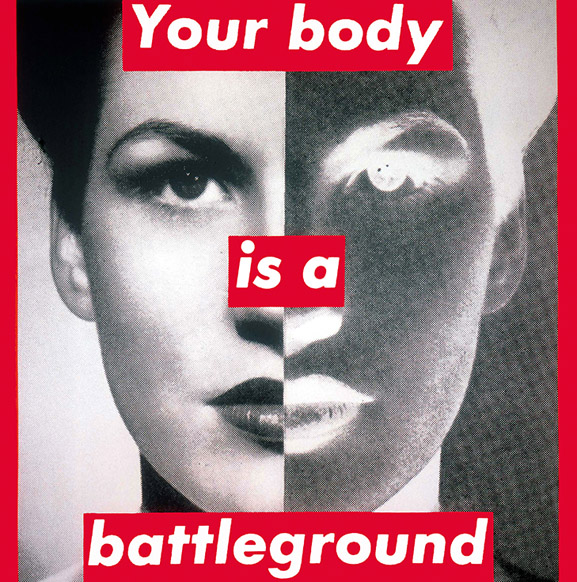

2.8. Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground), 1989

Both aesthetics and art making figured importantly in this conversation. As modernism’s formal and formalist regard for the body passed from fashion, new debates regarding the body’s social and political meaning came to occupy the stage. As Barbara Kruger’s photomontage Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground) (1989) confirms, by the end of the twentieth century the body itself had become a site of struggle (fig. 2.8). Did legislative, judicial and ecclesial leaders hold the right to determine the meaning of one’s ethnicity or the morality of one’s sexual practice or identity? As if to challenge all conventional thoughts on this matter, in the 1980s and 1990s numerous artists produced work that featured sexually explicit content: the performances of Karen Finley (b. 1956) and the homoerotic photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989) come easily to mind. The purpose of these works varied, of course, from wry aesthetic commentary and social protest to the bizarre sexual fixations and fetishes of individual artists. But whatever their purpose, Finley’s and Mapplethorpe’s works were intended to startle the viewer and, in doing so, to transgress conventional mores and manners with the hope of maximizing personal freedom and moral license.24

While works by Krueger, Mapplethorpe and Finley hardly invented the politics of the body, they championed a new ideological framework that came to be known as critical theory. The focus of this rising intellectual revolution, which received widespread endorsement from the humanities curricula of America’s leading universities, was ethnic and gender politics. The support that critical theory gained from innumerable artists eager to support a cluster of ideologically divisive issues—including women’s rights; gay, bisexual, lesbian and transgender preferences; the dignity of the physically impaired; and ethnic diversity—was nothing less than viral.25 Thus, in the closing decades of the twentieth century a revolution centered on personal rights ensued. From education to commerce and politics to entertainment, no part of the American social or economic fabric was untouched by this agenda.

This review of the figurative tradition in the modern era—its abstraction, exploitation and politicization—points to a complex and summative reality: the brokenness of our corporeal being.26 If cubism anticipated this, it is the sculptures of German-born Hans Bellmer (1902–1975) that established the fragmented body as a modern category.27 Bellmer’s odd-looking photographs and sculptural assemblages appear to be fashioned from female limbs, torsos, breasts and buttocks. And while these constructions surely find their origin in the surreal erotic fantasies of the artist, in the end they resurface as a Frankensteinian nightmare.

At the close of the century, art critic Roberta Smith wrote, “These are the days of underwear as outerwear, X-rated fashion photography, devolving standards of modesty and privacy, and relentless image bombardment. These are the days of ubiquitous naked bodies, and sexual references in contemporary art.”28 The sexed body of modernism was in fact a broken body.

BROKEN BODIES

Unexpectedly, in the 1960s and on the heels of the pop art movement, drawing, painting and sculpting the figure enjoyed a vigorous revival. In the movement known as new figuration, the body was once again a primary subject for painters, photographers and sculptors such as Frank Auerbach, Eric Fischl, Lucian Freud, Robert Graham, David Hockney, Sally Mann, Robert Mapplethorpe, Philip Pearlstein, David Salle and Kiki Smith.29 Generally speaking, the task of these artists was to document the body in the context of modern life. As painter Lucian Freud (the grandson of Sigmund Freud) explains it, “For me, painting people naked, regardless of whether they are lovers, children, or friends, is never an erotic situation. The sitter and I are involved in making a painting, not love. These are things that people who are not painters fail to understand.”30 Describing Freud’s paintings, one writer wondered: “Isn’t the potential of paint to become flesh and not merely simulate it what all [of his] works celebrate?”31 Similarly, figurative painter Philip Pearlstein comments, “The act of re-creating the visual experience of the models in front of me is absolutely absorbing, leaving no room for extraneous thoughts, sexual or otherwise.”32

One realist painter, Melissa Weinman, depicts Christian martyrs in contemporary settings as a means to explore what she terms “unredeemed pain.”33 This idea animates one of her most arresting paintings, St. Agatha’s Grief (1999), in which two “Agathas” stand back to back in full-length profile. The garment of the figure on the right is bloodied, and her chest is flattened, indicating that her breasts have been severed from her torso. It is a gritty image that invites the viewer to wonder whether Weinman is depicting Christian faithfulness or the ravages of cancer. Likely both. Writes one reviewer: “These icons are just like us; they are us; their blood is wet; their feet hurt; their hearts break. Let your mind reach over time, she seems to goad us, and see them as they were, as they are, not as relics but as human beings suffering the same woes as us.”34

As noted, the history of the body and its treatment during the modern and postmodern period is neither linear nor tidy. Alongside the new figuration, another submovement known as body art emerged in the 1960s and 1970s.35 It included everything from self-mutilation to masturbation to sadomasochism. Disturbing, sometimes gruesome, performances by artists such as Marina Abramović (b. 1946), Vito Acconci (b. 1940) and Chris Burden (b. 1946) raised the profile of this enterprise.

For our purposes, at least one of these events warrants further comment. In 1974 Chris Burden completed a performance piece titled Trans-Fixed, in which the artist had himself “crucified” atop the hood of a Volkswagen Beetle. With nails piercing each hand, he sought to reenact the central icon of Christendom. Responses to Burden’s performance ranged from initial disgust and bewilderment to more considered explorations of the social and theological meaning of his body and, by analogy, the broken human body. It can be argued that Burden’s work was not different in substance from Munch’s The Scream (1893), painted more than eighty years earlier, since both works explored the “angst of being” that had become part and parcel of modern life.

Burden was hardly alone in calling on the central and classic Christian theme of crucifixion to advance his interests. In 1992 Benetton, the Italian fashion house known for its enigmatic and sometimes disturbing print advertisements, published the image of an AIDS patient whose anguished face and onlooking bedside friends bore a striking resemblance to Andrea Mantegna’s The Dead Christ (c. 1500) (plate 2). In the Benetton ad, AIDS activist David Kirby lies in a hospital bed at death’s edge surrounded by his grieving family. In featuring this advertisement, Benetton and its designer Oliviero Toscani appear to demonstrate their solidarity with the gay community. Comments Toscani, “I called the picture of David Kirby and his family ‘La Pieta’ because it is a Pieta which is real.” He continues, “The Michelangelo’s Pieta during the Renaissance might be fake, Jesus Christ may never have existed. But we know this death happened. This is the real thing.”36

Much in the spirit of the sexual politics and critical theory noted at the close of the previous section, Benetton, with the publication of its AIDS ad, consciously entered what was, even in the 1990s, risky social and political territory. One wonders, had Benetton’s marketers appropriated the grim reality of the AIDS pandemic to establish the appearance of being a socially progressive brand and, therefore, to expand its market in the youth culture? Or, conversely, was Benetton responding to the AIDS crisis with genuine humanitarian concern well before it became fashionable to do so? Having launched its marketing strategy in uncharted waters, the questions surrounding Benetton’s sincerity remain.37 However one assesses the situation, in the Benetton advertisement art, life, disease and death embrace uneasily at the forefront of fashion.

TENTS AND TEMPLES

Like all saints and sinners, we exist as carnal beings—a term derived from the Latin root carnis, meaning “flesh” and belonging to a family of words such as carnivore, carnage and, notably, incarnation. The base connotation of these terms and their respective allusions to sexuality, appetite and slaughter have caused some in every age to disparage our embodiment. The fact of our mortality is unsettling. And across the centuries, the abiding inclination to denigrate our bodies sponsored at least two notable heresies: Docetism, the claim that Jesus did not have a real body, and Gnosticism, the conviction that genuine spiritual knowledge exists in a realm apart from our embodiment in this dull, material world.38 In both instances, material being is thought to be antagonistic to spiritual enlightenment. While Western Christian thought generally discarded these views, it often favored the Platonic dualism of body and soul.

As underscored throughout this chapter, evidence of the body’s temporality and glory is shot clear through the Western figurative tradition. For Christians seeking to make sense of this tradition, it follows that a biblical understanding of the self must regard physical being as an essential component of true spirituality.39 A robust theology of the body is needed. With this goal before us, two biblical images—the tent and the temple—provide useful categories for further reflection.

In his second letter to the believers at Corinth, Paul (himself a tentmaker) describes the body as an earthly tent, a temporary residence given to us during our journey on earth. Many Christians, especially amid physical suffering, have readily agreed with the apostle that “while we are at home in the body we are away from the Lord” (2 Cor 5:6).40 Meanwhile, in his first letter to this same community and as a corrective to their sexual misconduct, Paul reminds them that their bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 6:19) and charges to them to “glorify God” (1 Cor 6:20) through their bodies. Here the body is not a tent vulnerable to the effects of sin and death but rather a temple suited to host nothing less than the indwelling of God’s Holy Spirit.

Whether Paul’s reference is to the Jewish temple in Jerusalem or temples generally, he selects a sacred structure to serve as a metaphor for the body. This choice will remind Bible readers of Jesus’ heated exchange with the moneychangers, wherein he compared his body to the temple in Jerusalem (Jn 2:13-22). While the limits and vulnerabilities of our embodiment do present a myriad of challenges, the Bible is unequivocal in its insistence that the body is a physical site suited to host the dynamic relationship between the divine Spirit and our human spirit. To understand this more fully, the sections that follow consider four facets of our embodiment—its beauty, agency, sexuality and mortality—and their subsequent bearing on our spiritual formation.

Beauty. The second chapter of Genesis reports, “The LORD God formed the man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being” (Gen 2:7). Then, observing the man’s aloneness, God created other living things (Gen 2:19), but supremely it was his creation of the woman (Gen 2:22) that supplied the man with a true “partner” (Gen 2:20). According to the divine design, and set apart from other creatures, humankind—male and female together—bears the imago Dei, the image of God (Gen 1:26).41 That is, while the whole of creation abounds in aesthetic delight (Gen 1:31), the human form is a body of particular beauty.

From Genesis onward, two events—conception and birth—mark the beginning of human life. Caught up in this wonder, the psalmist writes, “I was being made in secret / intricately woven” (Ps 139:15), a declaration drafted long after Adam and Eve had fallen from grace.42 Apparently even bodies born in sin (conceived after the fall) are beautiful. The Christian view of corporeality, then, is that our bodies are beautiful simply because our physical being is a means given to us wherein we show forth God’s image. And it follows that the history of art simply confirms the fluid nature of aesthetics with regard to human beauty in every epoch and across all cultures. In this regard and with varying measure, we understand that particular standards for beauty—the proportion of one’s physique, the color of one’s eyes, the tone of one’s skin and the luster of one’s hair—are socially constructed.

Agency. The human body is more than an aesthetic object, a delight to the eye. It possesses impressive agency. With seeming ease, children—who display their own kind of radiant beauty—train their limbs to jump, pull, push and twist. This is the early evidence of their potential to flourish. As these young bodies gain form, skill and strength, they might someday fell a tree and fashion it into a cabinet, run a swift footrace, deftly finger an instrument, endure the hardship of military battle or wait patiently in a receiving line. Indeed, it is in and through these remarkable abilities and capacities that we act in the world. In turn, these acts are the threshold to human culture making. But more than this, these actions, rightly conceived, confirm that the imago Dei lies latent within us.

Sexuality. Both beauty and agency find particular expression in human sexuality. To be sure, our present age is obsessed with sexual performance and identity, but this fixation is hardly original, nor is it uniquely modern. Rather, the impulse to procreate and the desire associated with it are normative for Homo sapiens across the whole of human culture. Moreover, there is a fittingness to God’s design of our sexuality. For instance, the sight of an unclothed or partially clothed body is intended to stimulate sexual desire, but not in every case. That is, while unclothed or partially clothed bodies might be sexually provocative, there are notable and often lovely exceptions to this rule: the body of a newborn child; the physique of a dancer, athlete or laborer at work; the wise beauty of an elderly man or woman, especially their face and hands, to mention a few. With this distinction as background, we return to the matters of dress and undress and sexuality that are present in the biblical narrative.

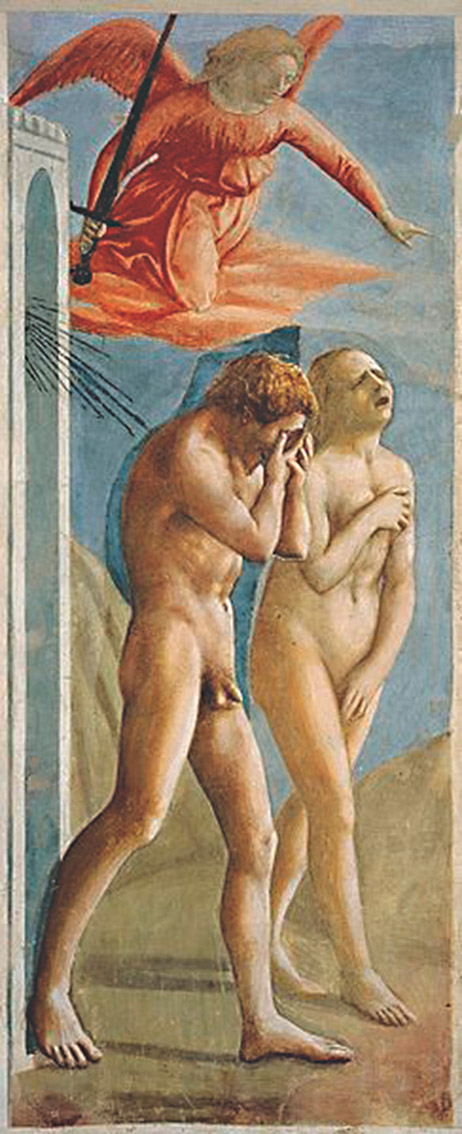

2.9. Masaccio, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, c. 1424–1427

While many assume that Adam and Eve’s rebellion against God was fundamentally sexual in nature, having to do with their nakedness, this notion is mistaken. Prior to their rebellion, Genesis reports that “the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed” (Gen 2:25).43 We also learn something about God’s intentions for marriage: “A man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh” (Gen 2:24). This core understanding of nakedness, marriage and heterosexual physical union has been the tradition of the church for centuries and remains widely accepted by most Christians, especially those within evangelical circles. It is only in the aftermath of Adam and Eve’s disobedience that shame enters the narrative: “Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves” (Gen 3:7).

There is not, I think, a more haunting image of this epochal fall from grace than Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (c. 1424) (fig. 2.9). This fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence depicts Adam with his face buried in his hands and Eve, who searches for a way to cover her exposed body. Surely the shame of this consumes the entirety of their beings—body, mind and soul. Following their banishment from Eden and in their postlapsarian condition, the man and woman’s physical nakedness became a visceral symbol of their spiritual exposure, the tangible evidence of their desire to hide from God (Gen 3:8). Only then, apart from God’s blessing and beneath the curse, is the problematic nature of their new sexual relationship revealed. For the woman, pain will now be associated with childbirth. For both, the fidelity that they once enjoyed will be displaced by a new relational dynamic: the man will dominate the women, and she will become his subordinate (Gen 3:16).

If, however, Genesis 3 calls on human nakedness to illustrate spiritual and psychological alienation, this sits in sharp relief to the affirmation that Adam and Eve were created to be ones who bore God’s image, this prior to their rush to put on the fig leaves that they had stitched together or to wear the garments that God made for them from the skin of animals (Gen 3:21).

While the unclothed body maintains a place of importance in the biblical narrative, its moral meaning remains inconclusive. But here Kenneth Clark’s distinction between nudity and nakedness (noted earlier in this chapter) provides a useful way forward. If we follow Clark’s line of reasoning, we might say that the pathos of Adam and Eve’s descent into disobedience, fear and shame as observed in Masaccio’s painting represents their nakedness. Meanwhile, the mutual delight and sensuality of the unclothed lovers described in Song of Solomon finds expression in their nudity:

How graceful are your feet in sandals,

O queenly maiden!

Your rounded thighs are like jewels,

the work of a master hand.

Your navel is a rounded bowl

that never lacks mixed wine.

Your belly is a heap of wheat,

encircled with lilies.

Your two breasts are like two fawns,

twins of a gazelle.

Your neck is like an ivory tower. (Song 7:1-4)

By design, this Hebrew poem summons images of unclothed bodies. And whether readers understand this biblical text to express a young groom’s passion for his bride or to serve as a metaphor for Christ’s love of his church, its eros is unmistakable. As we know, many pagan ancients engaged in practices such as temple prostitution, believing that there was a palpable connection between human sexuality and the fertility of their crops and cattle. They imagined a dynamic, albeit blurred, connection between eros and transcendence.

Could it be that human nakedness is an apt image of humanity separated from God by its willful disobedience, even as instances of human nudity provides us with images of redemption and renewal? The larger point is this: the biblical narrative frequently employs themes of nakedness, nudity and human sexuality to serve as parables of spiritual union and knowing. In this regard, Israel’s disobedience caused her to be described as the idolatrous whore of Babylon (Rev 17), even as the church is celebrated as the chaste virgin presented to Christ (2 Cor 11:2; Rev 21:9).

Mortality. Time passes. In due course, childish bodies bear the anxious confusion of puberty until, almost without notice, a blossoming occurs wherein awkwardness yields to the discovery of physical powers and comeliness (or lack thereof) in life and love. Those who have entered the second half of their lives recognize full well that new physical realities have settled in. Their bodies, now marked by the cares and hazards of the world, begin to expire. The wizened faces and uncertain steps of our elders confirm what lies ahead: we are made from dust, and to dust we shall return. Once only an abstraction, the psalmist’s words gain gravity:

As for mortals, their days are like grass;

they flourish like a flower of the field;

for the wind passes over it, and it is gone,

and its place knows it no more.

George Steiner is right to insist that we must not gloss the finality of physical death:

In death the intractable constancy of the other, of that on which we have no purchase, is given its most evident concentration. It is the facticity of death, a facticity wholly resistant to reason, to metaphor, to revelatory representation, which makes us “guest workers,” frontaliers, in the boarding-houses of life. . . . However inspired, no poem, no painting, no musical piece—though music comes closest—can make us at home with death, let alone “weep it from its purpose.”44

And in this matter the artist’s vision—say, the prematurely aged face of Walker Evans’s Allie Mae Burroughs (1936) or Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat (1793)—and the biblical record are allied. Even a simple child’s prayer captures the fact of our finitude:

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

This child’s prayer reminds us that our present, unredeemed bodies are the temporary residence of our being, but that our soul or essence will live on in a resurrected body (1 Cor 15:35-48). From cradle to grave, it is within flesh and blood that we “live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

In a deep Christian understanding of things, however, death and brokenness are somehow joined to redemption. Returning to the opening chapters of Genesis, the central fact of the drama is that Adam and Eve chose to eat fruit from the forbidden tree. Their agency opened the door to mortality. Their earlier innocence but a memory, they fled God’s presence even as he cast them from his garden. And as we have already noted, God extended a small mercy to these exiles and “made garments of skins for the man and for his wife, and clothed them” (Gen 3:21). Throughout our lives the preservation of our bodies remains a central concern, and this is magnified with the passing of life’s seasons. The prospect of death might be the most frightful aspect of our being, but in the end and empowered by the promise of resurrection bodies, Christians are those who stare death down.

Spiritual formation. While the reality of physical death leaves us wounded and often afraid, considerably more can be said about the spiritual dimensions of our embodiment, and the remainder of this section is given to consider them. Thus far, the vital connection between body and spirit is self-evident. That is, if those who follow Christ seek to become like him, then their spiritual formation must contend with and be guided by the material reality of their bodies. But as Dallas Willard points out: “It is precisely this appropriate recognition of the body and of its implications for theology that is missing in currently dominant views of Christian salvation or deliverance. The human body is the focal point of human existence. Jesus had one. We have one. Without the body in its proper place, the pieces of the puzzle of new life in Christ do not realistically fit together.”45

Willard’s observation has not seemed so obvious to many New Testament readers, who have been quick to point out that our “flesh” is a problem. For instance, in his letter to the churches in Galatia, Paul identifies the works of the flesh as “fornication, impurity, licentiousness, idolatry, sorcery, enmities, strife, jealously, anger, quarrels, dissension, factions, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and things like these.” Not a pretty list, and the apostle goes on to insist that “those who do such things will not inherit the kingdom of God” (Gal 5:19-21). Our sinful attitudes and behaviors pose a grave spiritual hazard, and because of this Paul presses on to say, “Those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires” (Gal 5:24). If these warnings about the flesh are not foreboding enough, during his dark night in Gethsemane, Jesus spoke these words to his weary disciples, “The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak” (Mt 26:41). Our flesh is at odds, at enmity with God.

Regrettably, decades of sermonizing and popularizing have skewed our understanding of “the world,” “the flesh” and “the devil.” By stripping biblical terms like these of their metaphorical meaning, one can wrongly equate the world with God’s created order, flesh with our actual physical bodies and the devil with some comic caricature. Indeed, this triad of resistance should be of considerable concern to all who seek after God. But the reference to flesh in these disparate accounts does not center on the physical body, and when we mistakenly advance such an alignment, we both degrade God’s intention for our physical being and curtail the work of the Spirit.

Such a degrading of the body was neither Paul’s nor Jesus’ intent, for both employed the term flesh as a figure of speech to illustrate two frontiers of human struggle. As we will observe in chapter three, the first of these has to do with unrighteous or unrestrained passions that stand opposed to the real presence and work of God’s Spirit. Second, and confirming what we have already observed, the body in which our spirit resides is finite and temporary. That is, our mortal bodies are subject to the same “bondage to decay” (Rom 8:21) such that “the whole of creation has been groaning in labor pains until now” (Rom 8:22).

Properly understood, the meaning of “flesh” in the New Testament does not entirely reverse our inclination to disparage our bodies. In Jesus’ day, for instance, it was commonly believed that a man born blind or bearing some other physical infirmity was encountering, in his body, God’s judgment for his sin or the sins of his parents. But Jesus was quick to challenge this assumption, saying, “Neither this man nor his parents sinned; he was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him” (Jn 9:3).

In fact, corporeality is not the enemy of one’s spirit but rather the stage on which moral goodness and evil are both acted out and acted on. That is, God acts on our bodies, and we, in our bodies, serve and worship him. Regarding the former, consider this: when a woman “who had been suffering from hemorrhages for twelve years” touched the hem of Jesus’ garment, her bleeding ceased (Mk 5:25-29). When Jesus ordered Lazarus, by then dead for four days, to “come out,” Lazarus arose and exited the tomb, grave clothes and all (Jn 11:43-44). Miracles, God’s supernatural intervention in the natural world, confirm that the membrane that separates the material from the spiritual is more permeable than generally imagined and that the spiritual is ultimately more real than the material.46 God, by his Spirit, provides physical healing, safety, rest and empowerment.

God, then, acts on and through our bodies, and in the same manner we respond to him. Christians have long understood the importance of subduing or denying bodily demands. To that end they have practiced spiritual disciplines such as fasting, prayer, meditation and solitude as means to open themselves fully to God’s Spirit. The truism “cleanliness is next to godliness” might seem quaint or even puritanical to some, but this allusion to personal hygiene finds a connection not only to the idea of ceremonial cleanliness but also with regard to personal transformation and identity. Whether it is found in the code of the Nazarites in ancient Israel (Num 6:1-21), particular behaviors mandated by the Levitical law, the rite of baptism or the metaphor that is resident in the gospel hymn “Are You Washed in the Blood,” a cleansed body is the tangible reminder that those who fear God seek purity of heart. While the various practices we have considered might invite disciples to refrain from particular comforts and indulgences for a season, the purpose of this restraint is not to punish the body but rather to eliminate passing distractions and discipline the will.

Adjacent to the concern for purity is the spiritual significance of physical posture. The position of one’s body in relation to God has been used to express everything from celebration (choreographed or spontaneous dance) to penitence (kneeling or falling prostrate for prayer) and from praise (hands held high) to grief (a defeated body crying out in despair). In all of these acts we note that the physical body is not assigned a volitional capacity or will. Rather, it is the mind and heart that generate moral decisions and then summon one’s body into action. Attending to our corporeality in this manner becomes a means for God’s sons and daughters to consecrate themselves. Here the mundane or even profaned body is made holy. This is not unlike the host and its transformation into the body of Christ within more sacramental Christian traditions. The higher goal is “that the life of Jesus may be made visible in our mortal flesh” (2 Cor 4:11).

To summarize, genuine Christian spirituality embraces the unity and coherence of our entire being and, as such, the body’s manifold functions, including pain and pleasure. Reflecting the spirit of Jesus’ teaching, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me” (Mk 8:34), is Jerome’s sentiment nudus nudum Christum sequi (“followed naked the naked Christ”).47 While the marketplace trains us to despise our bodies (in the guise of loving them), and though evangelical theologians have overlooked them (with eternity in view), the body is best regarded as a sacred vessel. These bodies—the ones we have loved and despised, protected and volunteered, the ones that have borne so many celebrations and sorrows—contain our conscious being. It is within these bodies that we are known and through these bodies that we come to know. The same bodies that are given in love are taken from us in death. No wonder artists have wrestled so mightily to come to terms with the human form, this habitation of our spirit that is universally shared by all living human beings.

A SACRED VESSEL

Across the spectrum of Christian belief, it is agreed that men and women bear the image of God. But this understanding is but a prelude to the simple yet monumental fact that God, who is unseen, was pleased to release his fullness in the body of Christ. That is, the Father chose the medium of human flesh as his preferred means to reveal his presence. As we have already observed, this embodiment of being began with the first Adam in Eden. But it finds its fulfillment in the second Adam, Jesus Christ (1 Cor 15:48-49). Those struggling to make sense of this quickly find themselves exploring territory that is alternately strange and strangely wonderful.48 In reference to the incarnation, Flannery O’Connor writes:

This is an unlimited God and one who has revealed himself specifically. It is one who became man and rose from the dead. It is one who confounds the senses and sensibilities, one known early on as a stumbling block. There is no way to gloss over this specification or to make it more acceptable to modern thought. This God is the object of ultimate concern and he has a name.49

Apart from Jesus’ corporeality in time and space, the gospel is not the gospel. That is, while many prefer to romanticize, allegorize and rationalize the humanity of Jesus, the “gospel truth” is that he possessed those bodily functions that are common to all of us—perspiration, urination and defecation (to identify those we regard as most ignoble, a fact that helps us to further grasp the meaning of Kiki Smith’s silvered jars considered earlier in this chapter). In other words, Jesus entered fully and “naturally” into the world, and there is no sacrilege involved in depicting the infant Jesus with a penis, feeding at Mary’s breast, passing through puberty, knowing hunger and thirst, experiencing physical exhaustion and bearing the agony of death.50

Our embodied condition has played a very central role in the artistic tradition, mainly because visual artists in the West had the task of representing the mystery on which Christianity, as the defining Western religion, is based—the mystery, namely of incarnation, under which God, as supreme act of love and forgiveness, resolves to be born in human flesh as a human baby, destined to undergo an ordeal of suffering of which only flesh is capable, in order to erase an original stigma of sin.51

Nor is it a problem to theorize that the adult Jesus experienced sexual longing (though no text records this). More than this, to the extent that he did encounter sexual temptation, he neither yielded to it nor was corrupted by it (Heb 4:15). Simone Weil puts it like this: “Christ experienced all human misery, except sin. But he experienced everything which makes man capable of sin.”52 In a verse added in 1978 by Mark E. Hunt to Charles Wesley’s original hymn “Come, Thou Long-Expected Jesus” (1744), Hunt reminds us that Jesus came “to earth to taste our sadness.” The vulnerability of our humanity is known to God, but, as Hunt insists, in Christ, God goes on to meet what we lack by becoming our “Redeemer, Shepherd, Friend.”

Come to earth to taste our sadness,

he whose glories knew no end;

by his life he brings us gladness,

our Redeemer, Shepherd, Friend.

Leaving riches without number,

born within a cattle stall;

this the everlasting wonder,

Christ was born the Lord of all.53

In becoming the servant to humankind, Jesus knew the water of his mother’s womb and the blood of the cross. The stress of Gethsemane and the disfigurement of his Roman execution confirm that he came to suffer. Indeed, both the internal organs and external members of his body absorbed the physical, mental and spiritual demands of human sin. Anticipating the moment and meaning of his death, Jesus issued this challenge to his disciples: “Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (Jn 6:53). As painter Bruce Herman explains it, “The brokenness of the Messiah, the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53, is the central mystery of cosmic and salvation history. God’s body broken for us is the source of hope and healing in a lost world. It is our communion, the only genuine possibility of meaning and belonging.”54

He was wounded for our transgressions,

Crushed for our iniquities;

Upon him was the punishment that made us whole

And by his bruises we are healed. (Is 53:5)

This season of Christ’s suffering has passed, of course, so that humanity is invited now to live inside the victory of Easter. God’s demonstration of triumph in the resurrection—wherein physical death is conquered—is the symbol of a new promise, and on the day of our own resurrection, we too shall receive imperishable bodies (1 Cor 15:35-57). According to Paul, “We are expecting a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ. He will transform the body of our humiliation so that it may be conformed to the body of his glory” (Phil 3:20-21). Our “adoption” leads to the eventual “redemption of our bodies” (Rom 8:23).

Even as we await the day when our lowly bodies will one day be perfected (Phil 3:21), we might also observe that the postresurrection, glorified and eternal body of Jesus bore the scars of his crucifixion. What does the record of these wounds suggest to us about our own resurrection? Will our new bodies also bear some perfected version of our scars, laugh lines and furrowed brows? We cannot know, but these considerations surely add intrigue to the artist’s exploration of the human form. Of this we can be certain: our present bodies manifest the imago Dei, and the incarnation confirms that this image is more than the emanation of our persona or the cultivation of our inner spiritual life. The eternity of our soul is secured in the truth of God and his kingdom, and the resurrection of our bodies will be the final demonstration of his power.

To conclude this chapter we return again to the promise of the figurative tradition. As we have noted, the bodies of contemporary men and women are burdened by the false messages they receive from the visual culture that surrounds them. The worlds of fashion, marketing and design advance a myth about our corporeality that must be deconstructed. In turn, this myth must be re-formed by the reality that is revealed in everything from ancient biblical stories, poetry and letters to the contemporary paintings of artists such as Melissa Weinman and Lucian Freud. Indeed, drawing, painting and sculpting the figure is often a consecrating act that empowers artist and viewer alike, as it increases their regard for the uniqueness, significance and dignity of all persons. Moreover, we are presented with the plain fact that the reality of our embodied existence also requires redemption. As painter Catherine Prescott proposes: “Our fears, our sorrows, our loves, our longings, are the inescapable reality of our daily, visible lives and if we can bring these things to the canvas in the current atmosphere of free-for-all appropriation of images, style, technique and identity, then we can perhaps present a solid alternative to the fractured world all around us.”55

Contrary to the profusion of digitally manipulated images that appear within the cinematic frame, on the pages of print journals and on the screens of our now-ubiquitous handheld devices, the consideration of real bodies is a study of common humanity. It is, therefore, not only an aesthetic endeavor but also a moral act. Regarding his work, figurative painter Edward Knippers comments: “I am trying to engage viewers in such a way that they have to contend with their own physicality in response to the work—come to grips with who they are as physical beings. Without that reality, the spiritual aspects of life will tend toward fantasy. In any practical day to day sense, we cannot have the spirit without the body. That is the nature of human existence.”56 Catherine Prescott urges, “If ever there were a challenge for those of us who are Christian representational painters, perhaps especially of the figure, the presentation of our humanness and our creaturely nobility in the face of a creation ‘that groaneth and travaileth,’ is it.”57

No wonder the ordinary act of viewing another’s face is among the most poignant in human experience.58 Indeed, the eyes do seem to be a window into the soul, and this invitation to know an other is what imbues the figure, the portrait and the self-portrait with such power.59 Our embodied hope is this: the splendor of creation, the surprise of the incarnation and the wonder of Christ’s resurrection all boldly endorse the spiritual merits of the physical world. God created material reality, he chose to inhabit the same in the body of Jesus and, at the end of time, he will create yet another material heaven and earth.

Finally, whether Christians at work in the visual arts should or should not direct particular energy to draw, paint, sculpt, photograph or film the nude human figure is not for this writer to determine. But of this we can be certain: in the broad scope of our lives with each other and with God, we embrace the reality that we are, in this season, embodied spirits. And to the extent that visual art and Christian theology are poised to address this foundational reality, both will be able speak to us in our day.