4

Be Careful Little Eyes What You See

You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live.

When shall I come and behold the face of God?

Every picture tells a story, don’t it.

We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that he admires it intensely. All art is quite useless.

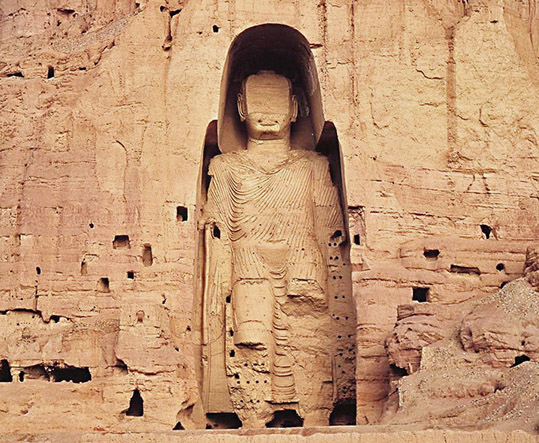

4.1. The Buddha, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, c. 500

On March 12, 2001, obeying the orders of their commanders, Taliban fighters commenced destroying two fifteen-hundred-year-old statues of the Buddha. This pair of landmarks—one towering an imposing 175 feet and the other 120 feet—had been carved deep in the stone cliffs of a remote region near Bamiyan, Afghanistan (figs. 4.1 and 4.2). At one time, some portion of each statue had been gilded, and ample evidence indicates that they were also decorated with lapis or ocher. The outcry against the desecration of these religious and cultural icons was international in scope. Still, the government of Afghanistan ignored the vehement protest of archaeologists, heads of state and religious leaders and made no effort to curtail or even forestall the horrific iconoclast actions of the Taliban. Even the economic threat of global trade sanctions could not prevent the soldiers from calling down a daily barrage of artillery fire and, finally, using dynamite to utterly destroy the monuments.1 Islamic fundamentalists like the Taliban are monotheists. They regard Allah as the only true god, and it follows that they do not tolerate the mention of other gods and abhor any image or idol that seeks to represent him.

4.2. The Buddha after Taliban desecration

The repudiation of representational images is the iconoclast’s central concern, and the production and adoration of such images has been the occasion for bitter disputes in all three Abrahamic faiths. It has naturally followed that the faith traditions that embrace an iconoclast position are generally those most wary of visual art and especially the rhetorical force of representational images.

Whether one is a thoroughgoing iconoclast or a sympathetic iconophile, the aims of this chapter are twofold.2 First, it revisits the besetting and perpetual swirl of controversy regarding the place and meaning of religious images—especially representations of God within the Judeo-Christian tradition. With this first objective before us, it makes sense to revisit Israel’s creation and adoration of the golden calf and then to examine the contrasting account of God’s command to erect a bronze serpent. Following this, we will review a trio of church controversies, including the debate surrounding the use of icons in Byzantium, the banishment of religious art and artifacts during the Protestant Reformation and the reinstatement of the same during the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Having assessed these events and debates, we will press ahead to our second aim: an exploration of how images and icons have functioned within conservative Protestantism, with particular attention to the yawning gap that lies between the stated beliefs of postwar American evangelicals and their practice of public and private worship.3

CALVES AND SERPENTS

The account of Israel’s golden calf stands as “Exhibit A” in the argument against the construction and adoration of images. In reading Exodus 31 and 32, it is not entirely clear why Aaron, Moses’ elder brother, yielded to Israel’s demand to fashion this idol. But the text suggests that Moses’ forty-day retreat to Mount Sinai had caused the prophet’s followers to doubt his actual return. Fearing that the promise of Canaan could not be realized apart from his presence, Israel’s leaders, it seems, appropriated the religious practices of their Canaanite neighbors.4

In the earlier chapters of Exodus we learn that, prior to their flight from the land of Egypt, God had instructed the people of Israel to plunder the wealth of their oppressors. In due course this material bounty would be used to construct the tabernacle (Ex 12:35-36). But, impatient with Yahweh, the Jews contributed their gold to the cause of casting and erecting the calf-god. In fact, God had already provided the Jews with several ritual means to encounter his presence, but Israel chose to forsake them. Indeed, the scandalous decision to fashion the golden calf demonstrates Israel’s failure to remember the powerful displays of God’s providence that they had already witnessed: his visitation of ten plagues on Egypt, his miraculous parting of the Red Sea and the manifestation of his presence in the cloud by day and the pillar of fire by night, to mention a few.5

Israel’s embrace of the Canaanite idol violated both the spirit and letter of two divine commands. First, God’s people had been charged to utterly destroy all idols originating from any of the pagan cultures that surrounded them:

The images of their gods you shall burn with fire. Do not covet the silver or the gold that is on them and take it for yourself, because you could be ensnared by it; for it is abhorrent to the LORD your God. Do not bring any abhorrent thing into your house, or you will be set apart for destruction like it. You must utterly detest and abhor it, for it is set apart for destruction. (Deut 7:25-26)

Here we must confirm the awkward fact that God’s command to Israel recorded in Deuteronomy is not different, in principle, from the actions taken by the Taliban troops in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, who employed explosives as their means to “burn with fire” the ancient carvings of the Buddha.6

4.3. Giotto, Faith, c. 1304

The second command given to Israel regarding idols is a corollary of the first: God forbade them from fashioning and then worshiping any idols of their own: “You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the LORD your God am a jealous God” (Ex 20:4-5). Regrettably, the practice of calf-worship had remarkable longevity in the religious life of Israel. Seven centuries later and in his effort to rival the significance of the temple in Jerusalem, Jeroboam, Israel’s godless ruler during the divided kingdom, erected two more calves, one in Bethel and one in Dan.7 Condemning this practice, the prophet Hosea protests:

And now they keep on sinning

and make a cast image for themselves,

idols of silver made according to their understanding,

all of them the work of artisans.

“Sacrifice to these,” they say.

People are kissing calves!

Therefore they shall be like the morning mist

or like the dew that goes early away,

like the chaff that swirls from the threshing floor

or like smoke from a window. (Hos 13:2-3)

Obeisance to an idol invites those who worship it to imagine that the idol’s material substance is somehow magical or that it can serve as a medium to the supernatural.8 As a visual commentary concerning the nature of idolatry, consider Giotto’s (1266–1337) fresco painting Faith and Infidelity, one of seven pairs that depict the vices and virtues and are a central feature of the considerably larger narrative program of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy.9 The female figure in Giotto’s left-hand panel upholds the Word of God in one hand even as she supports a cross in the other (fig. 4.3). Her faith is wholly dependent on God’s written and living Word. Meanwhile, the male figure in the right-hand panel supports the statue of an idol—presumably representative of pagan deities—in the palm of his upturned hand (fig. 4.4). The idol is inconveniently tethered to him. If he fails to uphold it, the idol will fall to hang like a millstone about his neck, thereby betraying him. Giotto’s image, which is not without humor, nicely illustrates the sentiments of the prophet Isaiah, whose words expose the foolish mind of any artisan who elects to craft an idol:

The carpenter stretches a line, marks it out with a stylus, fashions it with planes, and marks it with a compass; he makes it in human form, with human beauty, to be set up in a shrine. He cuts down cedars or chooses a holm tree or an oak and lets it grow strong among the trees of the forest. . . . Half of it he burns in the fire; over this half he roasts meat, eats it and is satisfied. He also warms himself and says, “Ah, I am warm, I can feel the fire!” The rest of it he makes into a god, his idol, bows down to it and worships it; he prays to it and says, “Save me, for you are my god!” (Is 44:13-14, 16-17)

It might seem that Isaiah’s reasoning supplies iron-clad support for the iconoclast position, but the larger Sinai story reveals three divine mandates that counter this conclusion: the planning and construction of the tabernacle and the ark of the covenant, including the use of symbols and images; God’s Spirit-filled call to Bezalel and Oholiab, artisans who possess the extraordinary set of skills needed to lead the effort; and the production and erection of the bronze serpent as an icon of healing. While each of these mandates merits lengthier discussion, for our purpose a closer look at the serpent narrative will suffice.

As noted, Israel’s forty-year sojourn in the wilderness was marked by impatience. Following a military victory over the Canaanites and en route to the Red Sea, they complained, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness?” In response, “the LORD sent poisonous serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many Israelites died” (Num 21:5-6). Realizing their desperate plight, the people repented and begged Moses to intercede to God for their deliverance. In response, “the LORD said to Moses, ‘Make a poisonous serpent, and set it on a pole; and everyone who is bitten shall look at it and live’” (Num 21:8).

Given God’s judgment on Israel for erecting the calf, coupled with Satan’s earlier personification as a serpent (Gen 3:4, 13)—not to mention the snakes’ predatory nature in the Numbers account and their general status as an “unclean” creatures according to Levitical law—God’s command to fashion the likeness of a reptile and then to lift it up on a pole appears counterintuitive, if not absurd. Nonetheless, this bronze casting became a means of God’s mercy so that, as promised, all who gazed on it would be rescued (saved). During Israel’s exodus and beyond, this image became a tangible symbol of redemption, so much so that according to Jesus it foreshadowed his atoning work: “Just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life” (Jn 3:14-15).10

In fact, the Bible makes frequent and positive reference to the use of visual symbols. Early in Israel’s formation, for instance, the patriarchs were instructed to build altars; upon Israel’s long-awaited entry into the Promised Land, God commanded Joshua to assemble two twelve-stone “memorials”—one in the middle of the Jordan and the other on its western shore—to serve as a signs (Josh 4:1-24); a pair of golden cherubim and other elaborate ornaments and utensils were created for the tabernacle (Ex 25:17-40); symbols of God’s presence were contained within the ark of the covenant (Ex 25:10-16); and Solomon replaced the portable tabernacle with a permanent temple that included the design and creation of numerous sacred vessels (2 Chron 2:1–4:22).11 Not least, Jesus imbued common bread and table wine with profound spiritual significance. The Bible supplies incontrovertible evidence that images and symbols that exist in service to God might be rightly held in high esteem.

But these positive biblical examples notwithstanding, the allure of refined materials and skillfully crafted objects enhanced by the artist’s vision and persona have tempted many to be more impressed by the passing work of human hands than the power and splendor of God’s presence.12 According to philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff, here “works of art become surrogate gods, taking the place of God the Creator; aesthetic contemplation takes the place of religious adoration; and the artist becomes one who, in agony of creation, brings forth objects in absorbed contemplation of which we experience what is of ultimate significance in human life.”13

THREE CONTROVERSIES

Having contrasted one account of Israel’s abuse of an image in worship with a second that highlights an acceptable, God-assigned use, intriguing questions arise. For instance, if an artist is both unable and forbidden to create an actual likeness of God, is she permitted to create a symbol or an image that represents God? If such symbols or images are permitted, what is their place or function in personal or corporate worship? In the history of the church, this pair of questions represents the substance of three precedent-setting debates.

The Second Council of Nicaea. In years that followed the conversion of Roman emperor Constantine (c. 274–325) to Christianity in 312, the center of the empire was relocated from Rome to Byzantium, which the ruler renamed Constantinople. It is said that Eusebius (c. 260–339), the bishop of Caesarea, would not allow the emperor an image of Christ. Nonetheless and in service to the church, artists of the day produced a great many liturgical objects and crucifixes of rare beauty, and this practice continued for several hundred years.14

Young Leo III (680–741), however, a brilliant military tactician and the seventh emperor of Byzantium, was a hard-bitten iconoclast. As John Julius Norwich explains, it might have been the influence of Islam on Leo’s family that created this disposition. In any case, “for some time the cult of icons had been growing steadily more uncontrolled, to the point where holy images were openly worshiped in their own right and occasionally even served as godparents at baptisms.”15 Nine years into his rule, Leo destroyed “the most prominent icon in the whole city,” a large golden image of Christ placed high atop the Chalke Gate, the principal entrance to the imperial palace.16 The popular reaction was immediate: a group of outraged women killed the commander of the demolition party on the spot. Matters continued to escalate:

In 730 he [Leo III] finally issued his one and only edict against the images. All, he commanded, were to be destroyed forthwith. Those who disobeyed would be arrested and punished. In the East, the blow fell most heavily on the monasteries, many of which possessed superb collections of ancient icons—together with vast quantities of holy relics, now similarly condemned. Hundreds of monks fled secretly to Greece and Italy taking with them such smaller treasures as could be concealed beneath their robes.17

Leo died in 742 and was succeeded by his son, Constantine V, who, like his father, hated icon worshipers and continued the cruel persecutions. “His most celebrated victim was Stephen, Abbot of the monastery of St. Auxentius. Accused of every kind of vice, he was stoned to death in the street, but he was only one of several thousand intractable monks and nuns who suffered ridicule, mutilation or death in defence of the icons.”18

On the occasion of Constantine V’s death, his eldest son, Leo IV, assumed the throne, but he died at the early age of thirty-one, leaving the rule of Byzantium to his wife, Irene. She was “a fervent supporter of images, who constantly strove against iconoclasm and all that it stood for.” With her son, Irene invited Pope Hadrian I to attend what would become the seventh ecumenical council, the Second Council of Nicaea (787), at which a great reversal occurred: “Iconoclasm was condemned as heresy” but with the proviso that icons were “to be objects of veneration rather than adoration.”19 It was agreed: signs, symbols and icons could again be permitted as a means to prepare the worshiper to embrace and adore God’s true icon, Jesus Christ.20

More than six hundred years later and at the height of the Italian Renaissance, it must have seemed that the place of religious icons and images was wholly secure. But while artists continued to produce extraordinary Christian art, they and their scholarly counterparts also demonstrated a renewed appreciation for pagan myths and ancient philosophies.21 Increasingly, they celebrated the human spirit rather than the divine. Powered by economic abundance, the compromised ambition of powerful Renaissance patrons and church leaders was often exposed.

The Protestant Reformation. In 1517 Martin Luther (1483–1546) inaugurated a sea change in the religious, social, economic and political life of Europe. In nailing his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg, the German cleric effectively launched the Protestant Reformation. Challenging the divine right of the pope and the cardinal doctrines and practices of the church in Rome, Luther held the conviction that, in matters of faith, sola scriptura (Scripture alone) and not the traditions of the church and its clerics should be the absolute source of all spiritual authority.

Once again, the visual arts were implicated and in two respects. First, art represented the considerable wealth and holdings of the church, a symbol of its oft-abused privilege. But more than this, the production of devotional images—especially efforts to produce likenesses of God—seemed to defy the biblical injunction against adding or subtracting a single word from Holy Scripture (Rev 22:18-19).22 That is, fashioning images of God was additive since its visual and material nature would, of necessity, communicate something of God’s true nature. The greater offense is that the mystery and beauty of God would now be represented by artists and artisans who were refashioning the God-created material world that was already bearing witness to his power and glory (Rom 1:20, 23). And so, like the iconoclasts who preceded them, Protestant reformers such as Zwingli and Calvin regarded the creaturely use of material forms to represent God’s ineffable nature a blasphemy.

As early as 1524, Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli (1484–1531) had paintings and sculptures systematically removed from Protestant churches in Zurich. And as historian Lee Wandel explains it, although the actual destruction of Christian icons and the whitewash of sanctuary walls in major European cities such as Zurich, Strasbourg and Basel were executed by relatively small bands of activists, it was the sermons being preached in the churches that incited the reactionary zeal of its parishioners.23

While the writings of French reformer John Calvin (1509–1564) often celebrate the beauty of God’s creation and demonstrate confidence in the place of beauty and the value of the arts, he too deeply opposed the presence of images and symbols in the church. According to Calvin, “Paul declares, that by the true preaching of the gospel Christ is portrayed and in a manner crucified before our eyes. . . . From this one doctrine the people would learn more than from a thousand crosses of wood and stone.”24 In concert with other reformers, Calvin believed that when someone placed his life before the measure of God’s Word, his idolatrous nature—the temptation to worship inert and visible things rather than the living and invisible God—would be made plain. The reformer would certainly have agreed with Lutheran theologian and reformer Martin Chemnitz, who wrote, “The best, surest, and most useful image of God and of Christ is the one which the understanding of our minds forms and conceives from the Word of God.”25 In this regard, extrabiblical ideas were especially objectionable so that highly popular religious images such as the pietà were regarded not only as fiction but, worse still, as heresy. It followed that artists who fashioned these kinds of work or the patrons who sponsored them could only be regarded as enemies of the gospel.

The Council of Trent. The charges of these upstart Protestant clerics and scholars, coupled with the violent actions of their followers, could hardly be ignored by the Roman Church. In a defensive posture, the Council of Trent (1545–1563) preserved the view that sacred images were legitimate provided they met certain criteria:

The holy synod enjoins that images of Christ, of the Virgin Bearer of God, and of other saints are to be had and retained particularly in the churches, and that due honor and veneration be shown them; not as though they were believed that any divinity or power resided in them, on account of which they are to be worshipped, or that anything should be requested of them, or that trust should be placed in images, as was formerly done by the heathen, who placed their hope in idols, but because the honor which is shown them is bestowed on the prototypes they represent, so that through the images which we kiss, and before which we uncover our head and bow down, we may adore Christ, and venerate the saints whose similitude the images bear, as has been defined by the decrees of councils, especially the Second Nicene Synod, against the opponents of images.26

These affirmations of the Catholic Reformation protected the interests of late sixteenth-century Italian artists who sought to create religious images, particularly works depicting the Godhead and Mary. In addition to renewing the church’s general support for Christian art, the council was careful to protect church interests. More practically, this meant that the form and content of the artists’ labors would be closely monitored to ensure that their works conformed to established church doctrines and enhanced the devotion of the laity.

In sympathy with the events that led to the Catholic reform, Ignatius Loyola (1491–1556), founder of the Jesuits, created a spiritual exercise that utilized both word and image. Exercise forty-seven states, “When the contemplation or meditation is on something visible, for example, when we contemplate Christ our Lord, the representation will consist in seeing in imagination the material place where the object is that we wish to contemplate.”27 Modern secular people might regard the ascetic constraints of Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises extreme or obscure, but they were not regarded as such by the renowned sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), who, “following the counsel of Ignatius, withdrew once a year into the solitude of a monastery to devote himself to spiritual exercises.”28 Similarly, the Spanish painter El Greco (1541–1614) gave himself to these same disciplines.

In the aftermath of Trent, these devotional practices demonstrate that the ongoing presence of sacred themes in the art of the day amounted, for some at least, to something considerably more substantially than the resolution of a formal problem or the completion of a public commission. Of this we can be certain: both the Catholic reformers and their Protestant antagonists understood the capacity of religious images to codify theological understanding and secure the affection of worshipers. For this reason the ratification of Trent held profound aesthetic and ecclesiastical implications.29 In this regard art historian A. W. A. Boschloo compares the painter’s vocation to that of a preacher:

The painter is a preacher differing from the “true” preacher only to the extent that he addresses the people with image and not with words. Like the artist, the preacher is advised to adhere literally to the biblical text and not employ complicated imagery, but to penetrate his audience’s heart with simple unembellished terms. Useless eloquence and rhetorical fireworks are reprehensible; they testify only to the speaker’s vanity, while it is really the spiritual welfare of the faithful he should have at heart.30

Modern divergence. A mere half-century after the ratification of Trent, boatloads of colonists crossed the Atlantic to establish communities in America. These Puritans, Quakers and other low-church or free-church Pietists sought a simple word-based, congregational approach to worship. They were iconoclast in every respect.31 And while later groups such as the Shakers and eventually the Amish upheld similar views, the aesthetic disposition of America’s religious founders indelibly marked the nation’s attitude toward the visual arts.32

Having noted the iconoclasm of the Protestant Reformation and the centrality of this mindset to the early colonizers of America, it seems important to remember that the iconoclastic impulse is not unique to Christianity or, for that matter, even to religion. A diverse range of social, political and aesthetic revolutions and reforms, often secular in nature, have called for the annihilation of images. During the French Revolution (1789–1791), for instance, angry mobs smashed stained-glass windows and Gothic sculptures. As we observed in chapter three, claiming aesthetic affiliation with Shaker sensibilities, 1960s minimalists were no less radical. In pursuit of referent-free objects, they directed their creative attention to inert material and pure form, hoping to resist the tug of either spiritual transcendence or political engagement. Similarly, as American forces invaded Iraq in 2003, statues and images of brutal dictator Saddam Hussein were gleefully toppled and defaced—this only two years after Taliban soldiers had destroyed the Buddhas in Bamiyan (fig. 4.5).

Despite America’s iconoclastic Protestant roots, contemporary Americans are essentially iconophiles and radically so; that is, they rely on the visual to represent their passions, preferences and beliefs. Nowhere is this more evident than in the popular appropriations of the term icon. For nearly two millennia this word was a referent to objects or images representing God. But in recent decades icon has been assigned new duties; today the term signifies the adulation of popular personalities, the focus of consumer desire and the graphical interface that appears on millions of computer screens.33 The dramatic secularization of this term is now so thorough that even the most committed Protestant iconoclast might be inclined to appreciate Pope John Paul II’s conviction that

the rediscovery of the Christian icon will . . . help in raising the awareness of the urgency of reacting against the depersonalizing and at times degrading effects of the many images that condition our lives in advertisements and the media, for it is an image that turns towards us the look of Another invisible one and gives us access to the reality of the eschatological world.34

EVANGELICAL ICONS

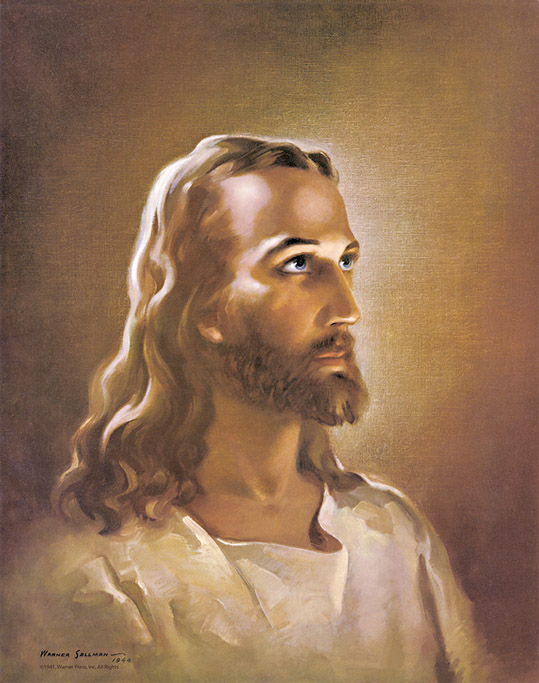

4.6. Warner Sallman, Christ at Heart’s Door, 1942

Not a few evangelical readers who have followed my account thus far of the icon and its alter ego, the idol, might imagine that this business is not much their concern. But they are mistaken. To illustrate the point I will again reference my own Protestant upbringing. In the church of my youth, a picture of Jesus occupied the central place on the front wall of our main Sunday school room. It featured a lighted door at nightfall, and before it stood Jesus patiently knocking. Painted by a woman in our congregation, it was a persuasive rendering—a copy—of Warner Sallman’s Christ at Heart’s Door (1942) (fig. 4.6), which itself owes a substantial debt to William Holman Hunt’s Light of the World (1851–1856). Considerable care had been taken to mount the woman’s work in a gold frame and to illuminate it from above. Apart from the stained-glass window at the front of our sanctuary (another image of Jesus), this picture was the only “original” work of art in the church.

Decades later I viewed Sallman’s Christ at Heart’s Door in an exhibition of his work on display at the University of Chicago.35 Sallman (1892–1968) “lived his life in Chicago, where he was trained as a commercial artist at the School of the Art Institute.”36 Without a doubt, the artist’s most popular work is his Head of Christ (1940), and this painting in its original state was also on view (fig. 4.7). In Protestant America, Sallman’s Head of Christ—a blue-eyed and Nordic-looking Jesus—occupied a place of honor in countless churches and Christian homes. Some calculate that this painting has been reproduced more than 500 million times. Moreover, having completely penetrated the nation’s postwar mentality, for many the painting functioned as nothing less than an authorized portrait of the Savior.37

4.7. Warner Sallman, Head of Christ, 1940

In theory the Protestant Reformation should have steeled fundamentalists and evangelicals against the production and distribution of such images. But even as they looked askance at Catholic devotion to, say, the Stations of the Cross or the Eastern Orthodox veneration of icons, largely because of the power of Christian publishing they embraced Sallman’s work—as well as a host of images inspired by the Bible—without reservation.38 Suffice it to say, if the King James Bible was considered to be the translation that best represented God’s Word as he intended it to be read, then Sallman’s painting was thought to be a reliable depiction of God’s Son.

In fact, the postwar evangelical appetite for such images was voracious. In 1966, for instance, Kenneth Taylor produced his Good News for Modern Man, a widely released, reader-friendly paraphrase of the Bible filled with simple line drawings used to illustrate a variety of scenes and stories. Published by the American Bible Society, an estimated 225 million copies are in circulation. The illustrations for this bible were created by Annie Vallotton (1915–2013). In her effort to supply these drawings with a “modern look and feel,” Vallotton did not assign a particular character to the figures or their faces. To twenty-first-century viewers, Jesus, John the Baptist and her other depictions might have the look and feel of alien invaders. But beyond Vallotton’s illustrations for Good News for Modern Man, consider this: each year millions of Christians enthusiastically send and receive Christmas cards that, without qualification, depict the Holy Family at rest before the Bethlehem manger with the Christ child and choirs of angelic beings singing “Glory to God in the highest.”

Meanwhile, illustrated Bibles and Christmas cards pale in comparison to the more recent and extraordinary confidence evangelicals have conferred on cinematic representations of Jesus. Consider Campus Crusade’s Jesus film. Translated into 1,420 languages, this film has been screened around the globe with a viewership estimated to be in the billions.39 The astonishing distribution of the Jesus film is regarded by some as a primary contribution to world evangelization and, not without irony, the film has been viewed in thousands of evangelical churches that are otherwise as “cleansed” of icons, paintings and sculptures as any in Calvin’s Geneva. Supporters of this project defend its pedagogical value, its usefulness both in teaching the faithful and in communicating the story of Jesus to the unchurched.40 But perhaps the greatest irony is this: though unwilling to display a crucifix on their sanctuary walls, in 2004 conservative Protestants bused record numbers of their congregants to local theaters to view Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, a graphic and decidedly Catholic enactment of Jesus’ suffering and death.

These wildly popular receptions should not lead one to conclude that in postwar America the iconoclastic spirit that was once so foundational to the establishment of American fundamentalism and evangelicalism has substantially vanished. But generally speaking, “imaging” Jesus became an accepted practice—accepted, that is, unless these images were either not to their liking or at odds with their interpretation of the biblical account. If they failed either of these tests, they would meet harsh evangelical resistance staged on one of two fronts: edgy or controversial films such as Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and Denys Arcand’s Jesus of Montreal (1989) would be either boycotted or ignored. Meanwhile, in conservative evangelical settings, a deep mistrust of icon veneration remained.

Thus far we have considered the relative merits and demerits of religious images in Christian life and worship and observed that, contrary to their theological and historical roots, twentieth-century conservative Protestants were in fact rabid consumers of Jesus images. But a deeper and more penetrating matter remains, and it has to do with the increasing use of images in evangelical spiritual formation.

OBJECTS OF DEVOTION

In some evangelical circles and especially in the 1980s and 1990s, it was not unusual for Henri Nouwen’s thoughts regarding Jesus, the simple life and compassion for the needy to turn up in a Sunday sermon or a small group discussion. But from time to time even Nouwen’s Protestant enthusiasts could find the priest’s Catholicism disconcerting. Such is his meditation on an image of Jesus fashioned by world-renowned Orthodox icon writer Andrei Rublev (c. 1360–1430).41 In Nouwen’s essay The Road to Daybreak, the priest explains how, after pondering Rublev’s icon for several exasperating days, he was led to a direct encounter with Jesus:

As I look into your eyes, they frighten me because they pierce like flames of fire my innermost being, but they console me as well, because these flames are purifying and healing. Your eyes are so severe yet so loving, so unmasking yet so protecting, so penetrating yet so caressing, so profound yet so intimate, so distant yet so inviting.42

What shall we make of Nouwen’s epiphany? Did God’s Spirit use the tiny strokes of the icon writer’s brush to generate a connection between the priest’s physical vision and his heart, mind and spirit—a mystical encounter unbounded by words? Or did Rublev’s image simply function as a talisman, bringing forward what Nouwen already knew of Jesus from his many readings of the Gospels?

While evangelicals have considered Nouwen’s encounter a mostly Catholic or Orthodox event, their own devotional practices could bear remarkable similarities.43 Richard Foster, a devout Quaker, writes, “Sometimes it is good to close the eyes in order to remove distractions and center attention on the living Christ. At other times it is helpful to ponder a picture of the Lord or look out at the lovely trees and plants for this purpose.”44 Older evangelicals will recall the familiar refrain of Helen H. Lemmel’s hymn “Turn Your Eyes upon Jesus.” Written in 1922, it remained popular for many decades, including later interpretations and performances by Amy Grant and Michael W. Smith.

Typically, evangelicals have embraced and continue to embrace two primary devotional practices: Bible reading and prayer. In fact, visual imagination is critical to both. On hearing the Gospel account of, for example, Jesus calming the storm on the Sea of Galilee, a person might imagine Galilee’s choppy water and gusty winds as well as that next moment when Jesus commands the storm to be still. In her mind’s eye, she might see the sky brighten and serenity return to the water’s surface and calm come across the faces of the troubled disciples. While reading or listening to the story, a mental picture of the scene takes form. Similar phenomena transpire during prayer. When a person closes his eyes to pray, it is not unusual for a set of images to appear. Here the disciple can employ his imagination to recall stories and events; use a natural object such as a stone, a feather or a shell to contemplate God’s divine design; light a Christ candle; place a cross or crucifix in his hand; or even imagine the face of Jesus.

The larger point is this: the history of American evangelicalism and its relationship to material culture confirms that visualization has been central to its piety. Argues Foster, “We simply must become convinced of the importance of thinking and experiencing in images. It came so spontaneously to us as children, but for years now we have been trained to disregard the imagination, even to fear it.”45 What Foster and others like him propose is a devotional bridge that connects the visible to the invisible—one not unlike Jacob’s waking vision of angels ascending and descending in the night (Gen 28:10-17).

Father Sebastião Rodrigues, the protagonist in Shusaku Endo’s novel Silence, describes his encounter with the face of Christ as follows:

As for me, perhaps I am so fascinated by his face because the Scriptures make no mention of it. Precisely because it is not mentioned, all its details are left to my imagination. From childhood I have clasped that face to my breast just like the person who romantically idealizes the countenance of one he loves. While I was still a student, studying in the seminary, if ever I had a sleepless night, his beautiful face would rise up in my heart.46

While it is not clear how exactly God’s Spirit guides such transactions, it is surely the case that modern-day Bible readers and prayer practitioners reflexively consult a vast archive of movie clips, personal experiences, artist renderings and subconscious archetypes to complete these acts.47

Meanwhile, to those who find Foster’s line of reasoning either awkward or suspect, the sentiment of the children’s Sunday school chorus we considered earlier might seem apt:

O be careful little eyes what you see,

O be careful little eyes what you see,

For the father up above is looking down in love,

So be careful little eyes what you see.

Within the church, at least, the kinds of practices considered in this chapter continue to stir substantial disagreement. Some believe that any preoccupation with physical spaces, objects and images belonging to the material world should be set to the side so that one may approach God unhindered. Others, meanwhile, regard these same encounters as central to their devotional life. So, while the evangelical rank and file may fear that Nouwen’s interaction with the Rublev icon crossed into unacceptable territory, many of their most cherished practices bear a striking resemblance to his account.48

SEEING THE UNSEEN

Given the problematic nature of representing the divine, one might conclude that picturing God is best left to God. Indeed, the hiddenness of God’s face is a recurring biblical theme. Prior to meeting with Yahweh on Mount Sinai, for instance, God warned Moses, “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live” (Ex 33:20). And surely this is the Old Testament understanding of things: in powerful deeds and actions, God shows his hand but never his face.

A central figure in this ongoing controversy is theologian J. I. Packer and, in particular, the fourth chapter of his widely read book Knowing God. Commenting on the second commandment, he writes, “Just as it forbids us to manufacture molten images of God, so it forbids us to dream up mental images of him. Imagining God in our heads can be just as real a breach . . . as imagining him by the work of our hands.” As already noted, the actual practice of many evangelicals ignores Packer’s claim. But more than this, one is left to wonder how this theologian or any other disciple of Christ is able to comprehend God incarnate, God with us, apart from calling on his or her imagination. Perhaps Packer has been satisfied to conceive of God as a hyper- rational being or, alternatively, encounter him inside various emotions. In either case, most of us—especially artists—function differently and must object to Packer’s claim that “all manmade images of God, whether molten or mental, are really borrowings from the stock-in-trade of a sinful and ungodly world, and are bound therefore to be out of accord with God’s own holy Word.”49 In effect, Packer has dismissed nearly the whole of Christian art. Dorothy Sayers’s conviction on this matter runs entirely counter to Packer’s: “To forbid the making of pictures about God would be to forbid thinking about God at all, for man is so made that he has no way to think except in pictures.”50

It might seem that this line of reasoning from the Old Testament continues on into the New, where John’s Gospel states, “No one has ever seen God” (Jn 1:18). But then, with the stroke of his stylus, the Gospel writer declares that God has been seen! John explains, “It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known” (Jn 1:18). In these same verses John reminds us that the mission of John the Baptist is to “testify to the light” (Jn 1:8). Indeed, “the true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world” (Jn 1:9). Reading on we learn that when Jesus first appeared to this wilderness prophet, John declared, “I myself have seen and have testified that this is the Son of God” (Jn 1:34). On the next day the Baptizer saw Jesus pass by again and announced to all within earshot, “Look, here is the Lamb of God” (Jn 1:36). And on the following day, the Evangelist reports, Philip encouraged the skeptical Nathanael to “come and see” (Jn 1:46).51 And so John’s narrative continues on, the disciples seeing Jesus and Jesus, God’s Son, being seen. These early disciples were beginning to understand that in Christ the Father was showing his face.

Later on and having already ascended to the Father, Jesus appeared to Saul as he and his companions made their way along the road to Damascus (Acts 9:1-9). Saul, a learned Jew and a rabid persecutor of early Christians, was entirely transformed in heart and mind by his encounter with Christ. So much so that in later letters he would boldly assert that in Christ “all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (Col 1:19). Saint Paul’s conversion has been the subject of many paintings, most famously, perhaps, by Caravaggio (c. 1601) (fig. 4.8).52

The author of Hebrews writes, “He [the Son] is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being” (Heb 1:3). Whether one is an iconoclast or iconophile, the meaning of the incarnation is certain: the unseen God is seen through the veil of Christ’s flesh. This simple fact has redirected the whole of human history.

When we embrace this cardinal Christian doctrine and it radical impact, a kind of oddness settles in. For while the face of Christ is surely the central image of the Christian faith, there is no firsthand visual or even verbal record of Jesus’ actual appearance save, perhaps, for two lines from one messianic Hebrew poem written several hundred years before his birth: “His eyes are darker than wine, / and his teeth whiter than milk” (Gen 49:12).53 As early as the first century, however, symbols representing Christ made frequent appearance:

Jesus Christ was portrayed on the walls of the catacombs as a fish, a vine or a lamb. Fish were historically linked with the miracle of the loaves and fishes, and with the apostolic vocation to become “fishers of men.” The letters of the Greek word for fish, ichthus, stand for “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour,” and the sign therefore became a logo for the faith, carved on gravestones and on walls. The vine was for Jesus a symbol of his union between himself and his people, and a memorial of his passion.54

These symbols notwithstanding, there appear to be no likenesses of Jesus—not a single one—generated by artists who worked during his lifetime. How shall we account for this absence? Certainly, the Roman artists of Jesus’ day sculpted marvelous busts and figures of emperors, philosophers, military commanders and deities. Perhaps the Jewish observance of the first and second commandments forbade Gentile images of Christ. Or perhaps Jesus’ lowly origin—a poor Jew from Palestine—isolated him from artistic scrutiny. However one accounts for this initial absence, two millennia later we possess innumerable images of Jesus, and all of these are inventions conjured in the mind of an artist and rendered by an artist’s hand.

During the postwar period, the far-flung examination of Christian images and icons that we have considered in this chapter led to two straightforward conclusions. First, relatively few Protestant evangelicals were actually iconoclasts. To the contrary, their Christmas cards, the paintings and posters that adorned their walls, and their general viewing habits betrayed their deeper desire to possess images of Christ. Some, of course, continued to resist the use of religious images and icons, but it may be that this reluctance had more to do with their unfamiliarity with or backlash against other Christian traditions than with some carefully reasoned biblical or theological position.

Second, by the close of the twentieth century, significant numbers of evangelicals turned to embrace liturgical, iconic, sacramental and ecclesial forms and practices that lay well outside their own tradition. And not coincidentally, some evangelical churches in America became more open to visual art and more supportive of their members who sensed a call to create it. Meanwhile, to the extent that conservative Protestants embraced the iconoclasm of their sixteenth-century forebears, many serious visual artists concluded that they needed to worship elsewhere.

To make sense of the presence and meaning of images and icons within the church, this chapter has highlighted the contest between iconoclasts and iconophiles. But there is a second side to this coin: Protestantism’s preference for texts rather than images, and especially its unique regard for the Bible. This contest, which pits the verbal against the visual, is the central subject of the chapter that follows.