8

An Aesthetic Pilgrimage

Art has always been about meaning.

The Christian is the one whose imagination should fly beyond the stars.

For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.

See, I am making all things new.

In an article written for National Geographic, Chip Walter describes his first experience viewing the chambers of the Cave of Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, an important archaeological site discovered in 1994:

Around 36,000 years ago, someone living in a time incomprehensibly different from ours walked from the original mouth of this cave to the chamber where we stand and, by flickering firelight, began to draw on its bare walls: profiles of cave lions, herds of rhinos and mammoths, a magnificent bison off to the right, and a chimeric creature—part bison, part woman—conjured from an enormous cone of overhanging rock. Other chambers harbor horses, ibex, and aurochs; an owl shaped out of mud by a single finger on a rock wall; an immense bison formed from ocher-soaked handprints; and cave bears walking casually, as if in search of a spot for a long winter’s nap. . . . In all, the artists depicted 442 animals over perhaps thousands of years, using nearly 400,000 square feet of cave surface as their canvas.1

Archaeologically speaking, the cave’s spectacular drawings—some, Walter observes, “drawn with nothing more than a single and perfect continuous line”—are relative newcomers.2 In other places, scientists have confirmed the discovery of beads, carved bone tools, and ocher and stone objects fashioned by the human hand and estimated to be one hundred thousand years old.

Ancient artifacts, including extraordinary drawings of the sort found in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave, remind all who study them that it is the nature of human communities to generate a material culture. Made things, rendered images and built spaces record the imaginative acts and abiding values of the peoples who sponsor them. According to philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff, “[We] know of no human society or sub-society which has managed to live without the arts—by which I mean, without music and poetry and role-playing and story-telling and pictorial representation and visual design and sculpture.”3

When measured against art’s shimmering tour de force throughout history, it is fair to insist that postwar conservative Protestants demonstrated little to no interest in the visual arts. They did, of course, publish educational materials, produce devotional objects and construct houses of worship, but the character of these popular arts was predictably didactic and utilitarian. Stained-glass windows being the notable exception, conservative Protestants did not display art in their church parlors, statuary was absent from their sanctuaries, and handsome liturgical objects and finery held no pride of place in the low-church worship experience. From early in the twentieth century onward, one expected the edifice and interior of, say, a Baptist or Assemblies of God church to look and feel substantially different from their Lutheran, Episcopalian or Catholic counterparts.

If aesthetics was decidedly not a central concern for most postwar evangelical communities, salvation was: God saving men and women to himself and from the world. That is, evangelicals did not imagine that the aesthetic dimensions of their being—apart from music—had any bearing on their salvation. This commitment to a strong, demonstrable conversion was flanked on one side by steadfast allegiance to the authority of God’s Word, the Bible. Matching it on the other was a resolute devotion to personal holiness, the ongoing sanctification of every believer. This trio of commitments—conversion, the Bible and personal piety—shaped conservative Protestant priorities, and by mid-century it also guided popular understandings of God, morality and community for millions of Americans, even nonbelievers.

Since most evangelicals considered the highbrow aesthetic commitments of the art world anathema, artists who longed for a place where art and faith could thrive in fruitful union found themselves in a precarious position. If their Christian belief inspired devotion to Christ and his body, artistic success assumed uncritical alignment with the ideology and practices of the secular art world. As their church communities preached separation from the world, in equal measure the creative pursuits of these artists were relegated to the margins of church life. In many respects this was a rational divide, for just as the aesthetic expressions of the art world were not easily comprehended by the church, moral frameworks wedded to divine revelation left aesthetes confused. And so it followed that where one community saw no virtue in visual aesthetics—including the possibility that aesthetics (beauty) could be a path to transcendent reality—the other doubted the possibility that the real presence of God could be revealed in a book, the Bible. Consequently, each community harbored deep skepticism concerning the core convictions and practices that animated the other.

Tertiary education contributed mightily to this divide. From the 1950s onward, BFA and MFA degree programs at secular academies, colleges and universities swelled in popularity, and student enrollment skyrocketed. Almost without exception, these courses of study embraced a modernist aesthetic that only widened the breach between art and religion.4 In due course, art departments were also established at Christian colleges and universities. It followed that the faculty credentialed to offer instruction in these new programs were artists who had completed their MFA at secular institutions. While these newly minted professors could generally subscribe to the statement of faith and personal code of conduct of the institutions that employed them, it was their secular training that largely informed the philosophic and aesthetic commitments they brought to the classroom. Indeed, many of these art department faculty embodied the very tensions outlined in this book and, in due course, so also would their students.

Remarkably, during the postwar period almost no church-related Catholic or Protestant college or university art department encouraged students to make art for the church. And it remains the case that visual art directed to worship and liturgy is conspicuously absent from the curricula of these tertiary institutions. The reason for this is twofold. First, and as already noted, nearly all of the teaching faculty in these church-related college and university art programs completed their graduate training at secular institutions and had, therefore, no formal training in the liturgical arts. Second, the denominations that founded these institutions have been either disinterested in or opposed to finding a meaningful place for visual art in their worshiping communities. While a good many art departments at church-sponsored colleges and universities have flourished, the students who matriculate from these programs seldom bring their learning, skill and imagination back to the faith communities that have, at least in part, sponsored their education.

As we observed at the beginning of this book, from the mid-nineteenth century onward, artists of faith had been presented a false choice: an ultimatum insisting that art and religion could not reasonably coexist. Secular and even Christian art education reinforced this polarity, as did the social, critical and economic machinations of the art world. To manage this supposed conflict, artists in the Christian community found themselves opting for one of three perfunctory arrangements: they could remain in the conservative church and abandon their art, migrate to liberal Protestantism and enjoy a modicum of vocational support, or cast their lot with the art world, leaving their personal attachments to Christian belief behind. At the end of the day, each choice signaled a troubling loss of community. Conservative Christians attuned to the arts would need to find their way forward alone. Save for a few visionaries, most did not.

A primary objective of this study has been to understand why, in the second half of the twentieth century, American evangelicals and the modern art movement existed at such remove. During these decades this distance was the given condition. With the seven previous chapters of this book providing a rich context, this closing chapter aims to resurrect a measure of hope for those who believe they are called by God to be faithful artists. The thematic arc of this project requires nothing less.

A GLIMMER OF LIGHT

In the 1970s a few visionaries in the evangelical community commenced on an aesthetic pilgrimage. The backdrop for this development was surely the rise of the American counterculture. As the 1960s youth movement grew, it challenged and then overturned traditional hierarchical structures—establishment practices—on every front. To the uninitiated, the spirit of freedom and creativity present in the Aquarian age was intoxicating. For while conservative Christians talked about the joy of knowing Christ, the innovative music and fashion of the counterculture, coupled with its radical politics and liberated social mores, enacted a more visceral exuberance—a festival of present delights rather than the deferred promise of an eternal home.

For a loosely configured yet dynamic fellowship of culturally attuned evangelical intellectuals, artists, pastors and ministry leaders, the broad-reaching force of this social revolution required a ready response. Some rose to meet it. To achieve this, these evangelicals would need to step away from the reactionary posture that had bound them for so long to embrace new strategies for church growth, preaching, scholarship and social engagement. Nuanced missional paradigms, ones intending to be biblically faithful yet culturally open, did emerge. And Christian perspectives on the visual arts benefited directly from these.

In his 1973 book Art and the Bible, Francis Schaeffer asserted: “While the lordship of Christ over the whole world would seem to include the arts, many Christians will respond by saying that the Bible has very little to say about the arts . . . but this is just what we cannot say if we read the Bible carefully.”5 According to Schaeffer, if one believed in the Bible, it followed that one must hold the arts in high regard. For artists in the evangelical church, Schaeffer’s endorsement felt like a game changer. Indeed, not only had this popular Christian thinker granted Bible-believing Christians permission to accept the arts as a central feature of their story, but the apologist served notice to any in the church who might resist the idea. While the reach of Schaeffer’s speaking and writing was limited primarily to the conservative Protestant community, for Christian artists a promising light had appeared on an otherwise dull horizon.

Across several decades, many have criticized Francis Schaeffer’s “thin,” generalist approach to weighty philosophical, theological and social issues. Few, however, dispute the broad encouragement that he and his wife, Edith, brought to a generation who longed for the day when the gospel of Jesus Christ would be regarded as culturally relevant. And no group in the Christian community benefited more from their efforts than artists.

In 1970, three years prior to Schaeffer’s publication of Art and the Bible, his friend H. R. Rookmaaker published Modern Art and the Death of Culture.6 The Dutchman was a learned art historian, and his regard for modernism was evident throughout the book. Still, for believers eager to find a Christian voice in the modernist milieu, Rookmaaker’s critique offered little forward direction. Though insightful, it was not—as the book’s title suggests—a hope-filled account.7

In 1978, however, Rookmaaker published Art Needs No Justification, a considerably smaller essay.8 Like Schaeffer’s Art and the Bible, this work affirmed the relevance and legitimacy of the arts to the evangelical community. Just two years later, philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff published his book Art in Action, and that same year aesthetician Calvin Seerveld released Rainbows for the Fallen World.9 Within a decade, a handful of Reformed thinkers had articulated the case for Christianity and the visual arts. While it should not be imagined that Rookmaaker, Schaeffer, Seerveld and Wolterstorff were evangelical spokespersons per se, their commitment to the authority of Scripture granted them an audience with other culturally attuned theological conservatives. In due course, their speaking and publishing, coupled with growing enthusiasm from younger followers, created new space for art.10

The basis for this new openness centered largely on a conviction espoused by Schaeffer and his protégés: if Christians hoped to reach a “lost world,” then they needed to understand it firsthand. In other words, the context for Christian witness mattered profoundly. In practical terms, this revised understanding of evangelism caused increasing numbers of mission-minded evangelicals to view secular films, visit museums, listen to contemporary music and read modern literature and philosophy. Before long, evangelicals were sponsoring a wide variety of innovative endeavors that featured sophisticated cultural critiques and an ever-increasing sympathy for the arts. And here I would be remiss if I failed to note the founding of Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA) by art professor Eugene Johnson at Bethel College in 1979. CIVA—for which I currently serve as executive director—occupied a place at the very center of the discourse I am describing.

If from the 1950s to the 1980s mainline Protestants and some Catholics had taken the lead in faith-based arts initiatives, evangelicals increasingly became core participants. By the close of the century, a common love of art and belief in the redemptive power of the gospel generated positive if not unexpected alliances. Across denominational boundaries, collegial friendships were formed, guilds and associations were established, and fresh aesthetic life was breathed into existing Christian institutions. An art and faith movement had been born, and not infrequently evangelicals provided leadership.

In the wake of all this promise, however, two or more decades would pass before a more filled-out Christian understanding of the artist’s vocation would find expression.11 In fact, Schaeffer, Rookmaaker, Wolterstorff, Seerveld and others had always been attuned to the social and spiritual realities of the artist’s vocation. Nonetheless, most postwar evangelical leaders were either unprepared or unwilling to embrace this new moment either for art or for artists who belonged to their congregations or organizations.

From the 1990s onward the tide began to turn as some evangelical leaders and institutions revisited their wavering commitment to the visual arts. A flurry of promising ventures followed. These belonged, more or less, to one of four categories: the formation of professional societies and publications, print and online; fresh arts-related initiatives at Christian liberal arts colleges and universities; related graduate-level study and research, with notable developments in theological education; and a wide range of congregational initiatives. With regard to the local church, mainstream evangelicals began to celebrate the artist’s vocation, develop arts ministries, establish gallery spaces and exhibition programs, and introduce visual art into their preaching and teaching.

What grants this wide range of endeavors its authority, what lends gravitas to its cause, is the compelling breadth and quality of the artistic production that continues to occur. At the end of the day, the promise of the entire art and faith enterprise will be sustained only if artists in the community continue to make art of scope and substance.

Before pressing ahead, let’s consider an important footnote to this social history. Two opportunities to redress the seeming impasse between visual art and Christian faith had been present to conservative Protestants all along. First, they might have consulted the marvelously rich yet largely forgotten history of Christian art. For at least fifteen centuries or more and prior to the Protestant Reformation, there existed a vital visual witness to Christian piety, worship and thought. Since this world of art and architecture is cherished by both secular and religious persons and respected by cultural elites, church leaders might have called on it as a means to meaningfully engage the art world.12 But the iconoclasm of the Protestant tradition, nervousness about its alignment with a more Catholic past and the anti-intellectualism of its populist practitioners forestalled its ability to unpack these treasures. Second, conservative Protestants might have explored the art world’s abiding intrigue with spirituality—a fascination that prevailed throughout the twentieth century despite the endemic bitterness that so many modernists harbored toward organized religion.13 In this regard Marcus Burke’s caution is prescient:

At the outset of the twenty-first century, it is a sort of dereliction of aesthetic duty for a believing artist, whether recently converted or long since brought to faith, to turn his or her back on the immense power that modern design has brought to art. Above all, the ability of modernist techniques to achieve visual and philosophical transformations and access human psychology must not and cannot be ignored by any artist seeking to express the life of faith.14

By the century’s end, fresh winds did fill the sail of earlier developments, and for artists serious about Christian faith and art practice, it was time to enter or reenter the scene. But this new opportunity was limited and in two respects: their estimation of culture remained underdeveloped, and their understanding of the artist’s vocation skewed or miscast. To these topics we now turn.

THE CULTURE PROBLEM

In chapter one we noted H. Richard Niebuhr’s publication of Christ and Culture, in which the theologian outlines the virtues and liabilities of five possible relationships between Christianity and culture, the first being a position he termed “Christ against culture.” Those familiar with Niebuhr’s work generally agree that his Christ-against-culture position best represents the operational paradigm of most American fundamentalists and evangelicals from the late nineteenth century through to the close of the twentieth. Admittedly, evangelical beliefs and practices during those decades were more complex than this—influenced as they were by denominational particularities, regional distinctives and the social standing of their adherents. And as previously mentioned, in the closing decades of the twentieth century, evangelicals grew more open to the possibility that a variety of faithful responses to culture might be possible. But none of these changes or modalities reverse Niebuhr’s observation that the Christ-against-culture position is especially hostile to the arts.15 In fact, it is impossible to meaningfully engage art and the artist’s vocation while sidestepping or disabusing the reality of human culture. For artists hoping to remain faithful to Christ, three commonly held misperceptions about culture must be overturned.

The first and perhaps fatal flaw of the anticulture position is its failure to comprehend the intractable bond that each of us has to the whole of humanity—our communities of origin and then each subsequent community to which we belong. Modern men and women may theorize about living “off the grid,” but in reality planes and satellites continue to orbit planet Earth, the overflow of consumer waste routinely washes ashore and global digital networks pulse with data. To be human necessitates participation in the human community. That is, from financial management to education, from health care to commerce, each of us swims in a social pond. Common languages, customs and social policies, alongside less evident realities such as shared weights, measures and currencies, are essential to human flourishing. It follows that most men, women and children need an ordered civic life to thrive. No authentic discussion about culture can therefore occur when “others” who exist in that same culture are understood primarily as abstractions. According to Niebuhr, “Christ claims no man purely as a natural being, but always as one who has become human in a culture; who is not only in culture, but into whom culture has penetrated.”16

A second deficiency of most anticulture schemes is the assumption that movements like the art world or the evangelical church are monolithic. During the postwar period, both entities were loose federations at best, and their respective visions and programs fluid and contingent. Put differently, these enterprises behaved more like a school of fish darting about in deep waters than, say, a Roman legion on a measured march, and internal conflict and dissent was standard fare.17 In any case, the ever-shifting and sometimes fugitive character of these movements should forestall any impulse to universalize the beliefs and practices of one group and set these against the aesthetics and behaviors of the other. Faithful accounts will acknowledge a variety of actors whose manner and methods display divergent motives and ambitions. It is because of this that a bright line demarcating one community from the other is not easily drawn.

Third, twentieth-century evangelicals worried a great deal about membership—who belonged to their camp and who did not. The centerpiece of this concern was a fierce and long-standing debate regarding the nature of Christian conversion. If, they reasoned, eternal destiny is a matter of ultimate concern, then nothing is more important than the assurance of one’s salvation—to know for certain who has and has not passed from darkness into light, from death unto life. These impassioned and often fine-tuned discussions remain a central feature of evangelical identity, and especially as a counter to “cheap grace” or a hedge against universalism.

Not so subtly, this ongoing to-and-fro concerning the identity of the “saved” and “unsaved” underscored the anticultural stance of the fundamentalists and evangelicals who advanced it. That is, accompanying this spirit of separation was an abiding yet little-noticed assumption concerning class. The populist nature of conservative Protestantism inclined it to regard cultural elites—the moneyed, famous, powerful and privileged—as those least able to humble themselves and to take up the cross of Christ. There is a definite sense in which this conviction is rightly aligned with Jesus’ ministry and teaching, since Jesus boldly announced his Father’s heart for the least among us: the lame and the blind, the orphan and the widow, the beggar and those possessed by evil spirits. According to Jesus, the disciple who chooses the low road that leads to salvation must eschew money, status and privilege.18 Individual artists might or might not have belonged to this camp, but art-world elites—famous artists, collectors, museum patrons, curators and critics—surely did.

In this regard the rich young man is presented as the tragic exemplar (Mt 19:16-26; Mk 10:17-27; Lk 18:18-25). Though this affluent man longed to enter the kingdom of God, he could not heed Jesus’ instruction to “go, sell all your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mt 19:21). Fundamentalists and evangelicals reasoned that cultural elites, captivated by self-interest and pride, had chosen the wide road to their own destruction. At the same time, they imagined themselves accounted among Christ’s most faithful disciples. In the face of spiritual pride, of course, no measure of weakness, poverty or powerlessness is a guarantor of spiritual fidelity.

Twentieth-century fundamentalists and their evangelical heirs sought to establish a bulwark against liberalism, secularism and the worldliness of popular culture. At its best, the Christ-against-culture position was and remains a corrective to moral relativism and soteriological sloppiness. And here Niebuhr’s own estimation of the needed balance is instructive:

The relation of the authority of Jesus Christ to the authority of culture is such that every Christian must often feel himself claimed by the Lord to reject the world and its kingdoms with their pluralism and temporalism, their makeshift compromises of many interests, their hypnotic obsession by the love of life and the fear of death. The movement of withdrawal and renunciation is a necessary element in every Christian life, even though it be followed by an equally necessary movement of responsible engagement in cultural tasks. Where this is lacking, Christian faith quickly degenerates into a utilitarian device for the attainment of personal prosperity of public peace; and some imagined idol called by its name take the place of Jesus Christ the Lord.19

By the close of the twentieth century, the explicit challenge of secularism—a world without God—gained remarkable acceptance, especially among cultural elites. With this the optimistic theism that had marked so much of American life and culture five decades earlier dissipated. American religious history confirms that the Christ-against-culture posture did not abate this advance, nor did it offer much guidance to Christian disciples attempting to live faithful lives before the rising specter of pluralism.

In the opening decade of the twenty-first century, the cultural posture of evangelicals continued to evolve, and a pair of books deepened the conversation: Andy Crouch’s Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (2008) and, two years later, James Davison Hunter’s To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (2010). Crouch alerted his evangelical community to something that in retrospect should have been obvious: day in and day out, Christians make culture. Writes Crouch: “We make sense of the world by making something of the world. The human quest for meaning is played out in human making: the finger-painting, omelet-stirring, chair-crafting, snow-swishing activities of culture. Meaning and making go together—culture, you could say, is the activity of making meaning.”20 According to Crouch, the making of culture is best understood as the natural fruit of daily thought and labor. In the opening pages of Hunter’s book, the sociologist takes Crouch to task for his optimism concerning the power of grassroots efforts to effect longstanding change, but then goes on to advance his own thesis: only those with the requisite financial, social, intellectual and political capital—elites—have the capacity to inaugurate and then sustain deep cultural change.

I cite both positions here—Crouch’s confidence in the significance of imaginative grassroots endeavors (bottom-up) and Hunter’s endorsement of projects directed by and toward elites (top-down)—to highlight the evolution of evangelical thought and action with respect to culture. It takes little imagination, I think, to see that healthy communities who are eager to serve the commonweal will hope to discover genuine synergy between top-down and bottom-up operations. Whether one is inclined more toward Crouch or Hunter, both positions demonstrate the notable shift of some evangelicals away from reactionary separatism, on to apologetic engagement and eventually to culture making itself.

For younger, more progressive evangelicals who prefer cultural participation rather than separation, the older “culture war” has lost its force. And here we must acknowledge the substantially larger ideological conflict that engulfs these more particular iterations of evangelical community. That is, in this second decade of the twenty-first century, memories of Christian empire might persist, but the hegemony of Christendom no longer holds. Today Christian faith is but one of many options available to persons who choose or prefer to believe in God. And beyond these varieties of religious belief, the reigning ideological disposition of the West is now best described as post-Christian. Our emerging global context requires us to make peace with pluralism, to regard it as normative.21 Still, no matter which cultural critique or worldview one holds to, for Christians at least, neither Jesus’ commission to share the good news of the gospel with the world nor his command to love one’s neighbor has been rescinded.

Thus far we have considered the shifting cultural stage set on which artists in the evangelical community were left to work out their calling during the postwar period. Now we press on to consider the nature of this call.

CALLED BY GOD

A great deal has been written on the topic of Christian calling, and given its standing in the evangelical community, the topic remains a preeminent concern. Here is why. Beyond conversion to Christ, the most cherished position an evangelical man or woman can occupy is to be “called”—one who is able to discern and then pursue God’s will for his or her life. I have no quarrel with this general understanding. Indeed, Scripture abounds with accounts of God’s invitation to men, women and even children to assume divinely appointed roles and responsibilities in diverse settings and situations. In the Old Testament, God commanded Abraham, “Go from your country and kindred,” and he “went” (Gen 12:1-4). In the New Testament, Jesus invites his disciples to follow him, and they do so, leaving family, friends, possessions and careers behind. Bible readers are given considerable cause to imagine that, large and small, these kinds of invitations are normative and that God, according to his grace, provides those who follow him with the gifts and abilities needed to complete such tasks.

In their postwar zeal to evangelize the world, most conservative pastors and teachers reasoned that Christians belonged to one of two camps: a select group called to full-time ministry or a more general group needed to send and support those who had been called. A two-tiered system emerged in which persons called to serve as pastors, leaders and evangelists operated in the upper story and those tasked with providing prayer, encouragement and financial support occupied the lower.22 Across the centuries God’s people have supplied material support for those they deemed to be “set apart” to his service. Early evidence of this practice is God’s command that ancient Israel supply a tithe in order to support the Levites (Deut 18:1-8). Carried forward, this idea found radical expression in the early church, formed the operational heart of the premodern monastic movement that swept Europe and remained the foundation of missionary endeavors throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the postwar period, impressive acts of generosity, sacrifice and service advanced the global evangelical mission, and it is reasonable to suggest that this demonstration of altruism and devotion represents one of the movement’s finest hours.23

Acknowledging the strength of this position, there is ample reason to question the assumptions that undergird this two-tiered arrangement, not least because those occupying the upper story—persons who had themselves heeded a call to full-time ministry—were typically the ones commending the strategy. That is, pastors and other church leaders not only regarded this understanding of vocation as the biblical model; they occupied the podium from which it was announced. Because of this, the rich and expansive Reformational understanding that all believers are priests was often eclipsed or even forgotten.

If this two-tiered strategy effectively advanced particular expressions of the gospel message, too frequently it diminished the work of Christians who sensed no call from God to pursue “full-time” ministry. In its most flawed implementation, the calling of visual artists and countless other professionals was granted no standing, save in a supportive role. And more than bankers, or educators, or medical technicians, or ranchers, or auto mechanics, or military personnel, or homemakers, the usefulness of the artist’s calling was questioned most frequently (church musicians being the exception).24 How, after all, can making a painting measure up to the high calling of saving souls, healing the sick or feeding the hungry? Again and again, no ready or persuasive apologetic emerged.

Having served in full-time ministry for most of my adult life, but also being one with formal training in the visual arts and an ongoing studio practice, let me propose what I regard to be a more faithful approach to Christian calling. I term it “responsible agency.” As persons made in God’s image, we possess remarkable capacities. Our agency equips us to decide, act and create, to embrace opportunity and address need. But more fundamental than this, we have the ability to make moral, aesthetic, relational and spiritual decisions. This agency is basic to our being, so much so that the contours and capacities of our humanity cannot be understood apart from it.

The two creation stories featured in the opening chapters of Genesis establish the character of our agency. The first of the two is a kind of cosmic account that reviews the seven days of creation (Gen 1:1–2:3). The second finds its focus in the story of Adam and Eve (Gen 2:4-25). In these chapters, three primary realities about God’s nature are revealed: God exists in trinitarian community, he has the ability to create ex nihilo and he delights in blessing what he has made. With this understanding as broad context, in Genesis 1:27 we then learn about the nature of humankind:

So God created humankind in his image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

Together, male and female bear the imago Dei. In this regard the man and woman were charged to be fruitful and multiply (Gen 1:28a); granted dominion over the plants, fish, birds and mammals (Gen 1:28-30); placed in paradise to tend the garden (Gen 2:15); and tasked with naming the creatures (Gen 2:19-20). The evidence of their agency abounds. Adam and Eve are presented to us as imaginative, self-reflective and relational beings who have been invited by God to participate in what Dorothy Sayers describes as acts of “co-creation.”25

Notably, God does not ask the man, Adam, to accomplish his work alone. Moreover, while Adam’s powers are considerable—especially when compared to the other creatures—his capacity is limited and in three respects: he is constrained to exercise his freedom within the boundaries of the paradise where God has placed him; unlike God, Adam cannot create ex nihilo; and not all good things are available to him. Notably, Adam is forbidden from eating fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen 2:17).26

The unfolding story of the Bible visits the reality of human agency again and again. Early on, humankind’s impressive capacity to design, invent, make and build is confirmed. In the millennia that follow, this agency appears in everything from engineering and scientific theorizing, to philosophic discourse and transformative education, to corporate leadership and entrepreneurial risk taking. When rightly conceived, these practices are regulated by moral and aesthetic judgment, exist in service to God’s creation, including his creatures, and form the very foundation on which a full and meaning-filled life is constructed.

But we know that there is also a dark and disturbing side to this account. Scripture alerts us to the immense risk of granting fallible beings such potent agency. As the Babel account confirms, this agency is neither unbounded, nor is it (now in our postlapsarian condition) “naturally” poised to advance the good. To the contrary, creative agency can be employed to erect hubristic monuments (Gen 11:1-9), and throughout history our creative and imaginative capacity has been enlisted, again and again, to inflict unspeakable violence against other women and men, other creatures and creation itself. Not infrequently, art and architecture have been marshaled to advance reprehensible causes and conditions. But it is also the case that these same forms have been used redemptively to express deep, soul-searching lament.

To summarize, human agency is central to any understanding of Christian calling. Made in God’s image, we are invited to join with him to accomplish God’s work in the world. But if this general understanding is straightforward, it does not follow that identifying one’s particular vocation is an easy task. Rather, the pursuit of meaningful work can be all-consuming and appear to be a fool’s errand. This business is further complicated (but also blessed) by the reality that true vocation is worked out in a social context, a conflagration of morals, muses and manners in which realities such as class, race and gender figure importantly. In other words, the pursuit of one’s vocation necessarily intersects one’s prevailing cultural narrative, the Zeitgeist one inhabits.

With evangelicals having proclaimed their desire to reach the world for Christ, the perennial temptation in postwar evangelical America was to frame Christian calling too narrowly, thereby ignoring or eclipsing critical expressions of human agency. Too often religious believers inclined toward the arts were expected to conform the complexity of their lives and callings to a theological framework that lacked imagination and an understanding of discipleship that preferred method over nuance. The legitimacy of the artist’s agency, even its usefulness in the kingdom of God, was often questioned. We turn now to address the vocation of artist-actors themselves.

THE ARTIST’S VOCATION

Art is an impressive and often beguiling demonstration of human agency writ large in the world, and more than a few minds have sought to describe the artist’s task in relation to this. I believe that the artist’s calling is fulfilled when at least one of four human needs is addressed or met: supplying fitting design, advancing meaningful critique, generating palpable beauty or exploring ineffable mystery. If this reasonably outlines the possible range of an artist’s work, then it is not difficult to understand how the visual arts emerged.

Ancient man needed bowls and pots, fabric and clothing, tools and weapons, and furniture and shelter for sustenance and protection. Since the beginning of recorded history, Homo sapiens has been Homo faber, a worker, a maker of things. In preindustrial times, of course, these material goods were fashioned entirely by hand. In due course, familial and tribal structures would be organized around the acquisition and refinement of increasingly specialized making skills. Guilds and workshops were formed to cultivate mastery and increase productivity. Apprentices, usually younger family members, were mentored by elder generations, and those most gifted in making, embellishment and the ways of commerce rose in reputation and power.27

The earliest evidence of these kinds of activities in the biblical record appears in Genesis 4: “Adah bore Jabal; he was the ancestor of those who live in tents and have livestock. His brother’s name was Jubal; he was the ancestor of those who play the lyre and the pipe. Sillah bore Tubal-Cain, who made all kinds of bronze and iron tools” (Gen 4:20-22). In this ancient text, the arts are especially evident: musicians and metalsmiths existing on par with nomadic herdsmen. But material possessions were not humanity’s only need. Humanity’s social, intellectual and spiritual being required signs, images and icons (idols). It seems almost certain that Bezalel and Oholiab, the artist-artisans identified in Exodus, belonged to this kind of socioeconomic arrangement—Bezalel being the first person mentioned in the Bible to be filled by God’s Spirit, and God being the one who guided the artist’s mind and hand in designing and constructing the tabernacle (Ex 36:2).28

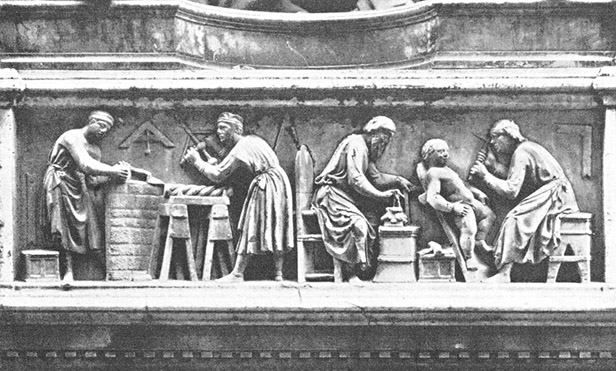

8.1. Carved stone relief, Oratory of St. Michael, Florence, 1339

In its way, God’s charge to Bezalel anticipates the later calling of the architects and artisans—workers in stone, metal, wood and masonry—who built Europe’s celebrated cathedrals.29 In this regard, a frieze located beneath the sculpture Four Crowned Martyrs on the exterior wall of the Oratory of St. Michael in Florence, Italy, is instructive (fig. 8.1).30 Though now a church and museum, the Oratory was built in 1336 both to store grain and to serve as a center for commerce. In 1339 each of the city’s professional guilds was invited to supply a statue of their respective patron saint to be placed in one of fourteen niches that now surround the building’s exterior. The distinctly premodern tableau of this carved stone frieze highlights what would have been a typical relationship between artisans and artists: skilled masons and sculptors laboring side by side to complete a larger commission.

During the modern period, sites such as the Cave of Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc (mentioned at the beginning of this chapter) and the Oratory of St. Michael, and artisans like Tubal-Cain, Bezalel and Oholiab, remained archaeologically and historically interesting. But building on the brilliant accomplishments of Renaissance artists such as da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael and Caravaggio and then rising to a fever pitch during the romantic period, the artist was recast as a “genius.” Increasingly, it was believed that the artist’s powers of invention, skill and facility should be celebrated, admired. For some moderns the “true” artist was believed to be a cultural prophet or priest. Painters, poets, sculptors and musicians were exemplars of emancipated modern selves. With this a deep chasm between ideation and craft settled in. As the fame of the artist-genius increased, artisans would, more and more, be regarded as mere makers of mere things.31 As William Deresiewicz explains it:

All of this began to change in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the period associated with Romanticism: the age of Rousseau, Goethe, Blake, and Beethoven, the age that taught itself to value not only individualism and originality but also rebellion and youth. Now it was desirable and even glamorous to break the rules and overthrow tradition—to reject society and blaze your own path. The age of revolution, it was also the age of secularization. As traditional belief became discredited, at least among the educated class, the arts emerged as the basis of a new creed, the place where people turned to put themselves in touch with higher truths.32

Having shed the burden of tradition and religion, the modern artist was no longer subservient to prescribed conventions or ruling institutions. Moreover, the advent of photography and its striking verisimilitude released artists from the burden of depicting people, places and events of note for posterity’s sake.

To illustrate the nature of this breathtaking transition, consider Claude Monet’s serial depictions of the Rouen Cathedral (1891–1895) (fig. 8.2). As art historian Carla Rachman suggests:

There was a long tradition of depicting the Gothic churches of northern France in a manner that emphasized their spiritual role, but Monet . . . was uninterested in entering the building. . . . The close-up viewpoint of most of the paintings treats the cathedral simply as an enthralling surface, faceted stone rising before our eyes like a man-made cliff eroded by the years.33

8.2. Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, 1894

In other words, the theological or sacramental significance of this Parisian cathedral was not Monet’s concern. Rather, fascinated by the quality of light as it played on the surface of the ornate structure, Monet appropriated the grand edifice to his aesthetic purposes. In the end, the thirty paintings in Monet’s Cathedral series—over which he labored for several years—are most admired for their evocative, shimmering color, the plastic qualities of his paint.

For many centuries Europe’s grand churches and cathedrals had been places of rich spectacle and, more practically, centers of religious, social and economic power. As the modernist aesthetic gained influence, this extended season would end abruptly and, with it, the vitality of Christian art. Compelling exceptions—the paintings of Vincent van Gogh, the prints and paintings of Georges Rouault, the biblical art of Marc Chagall, to name a few—would continue. But on entering the twentieth century, the art world would mostly regard Christian art as anathema, declaring it to be (as it often was in popular forms and expressions) riddled with kitsch and compromised by sentimentality.

Though seldom compared or contrasted, concurrent with these mostly European developments in the art world, eighteenth-century American evangelicals were witnessing widespread revivals or “awakenings” stirred up by the “the spell-binding preacher George Whitefield, the indefatigable evangelist John Wesley, and the brilliant theologian Jonathan Edwards.”34 Late in the nineteenth century, popular evangelists such as Charles Finney, Dwight L. Moody, Billy Sunday and Rueben A. Torrey would gain impressive popularity, and their ministries were aided by theologians such as Augustus Strong, Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield. These men, alongside a host of others, would shape the public character and evangelistic mission of conservative Protestantism for the rest of the century.

But the crisis of modernism had already begun in Europe, where, as noted, the artist’s vocation was being dramatically reconfigured. From the mid-eighteenth century onward, the grand narrative of Christendom would be cast on the ash heap of history, and modern art tasked to find meaning and purpose apart from traditional religious belief. The restless spirit of modernism and its desire to usher in new political regimes, overturn social conventions and inaugurate utopian dreams had fully surfaced. It was, in a sense, a mad rush away from the past—from histories believed to curtail expressive freedom and toward a future yet to be invented.

Where art and faith are concerned, these historical developments lead naturally, I think, to six intriguing questions. First among them is this: What, after all, is the artist’s work or calling? It seems unlikely that this substantially modern question much occupied the mind of premodern makers. But as the obligations of utility, religion and realism were sloughed off, the artist’s task or calling was redirected to one of two primary functions: either stimulating personal expressive freedom, including at times the obligation to speak truth to power, or simulating transcendent encounters, supplying a suitable replacement for the efficacy of religious devotion and ritual. Consider the words of British painter Ben Nicholson (1894–1982): “Painting and religious experience are the same thing, and what we are all searching for is the understanding and realization of infinity—an idea which is complete, with no beginning, no end, and therefore giving to all things for all times.”35

Aided by the startling rise of consumer culture during the postwar period, art and design were allied to a third cause: the highly profitable yet contested prospect of gathering the spectacular tools needed to gain market share. In the aftermath of the Great Depression and the sacrifices of World War II, the behemoth of consumer culture swelled to meet material desires stimulated by rising affluence and increasingly liberal mores. The long season of destitution had passed.

Returning then to the prospect of the artist’s calling, consider Frank Stella’s (b. 1936) compelling reflection on the nature of painting, which he published in 1986:

The ephemeral quality of painting reminds us that what is not there, what we cannot quite find, is what great paintings always promise. It does not surprise us, then, that at every moment when an artist has his eyes open, he worries that there is something present that he cannot quite see, something that is eluding him, something within his always limited field of vision, something in the dark spot that makes up his view of the back of his head. He keeps looking for this elusive something, out of habit as much as out of frustration. He searches even though he is quite certain that what he is looking for shadows him every moment he looks around. He hopes for what he cannot know, what he will never see, but the conviction remains that the shadow that follows but cannot be seen is simply the dull presence of his own mortality, the impending erasure of memory. Painters instinctively look to the mirror for reassurance, hoping to shake death, hoping to avoid the stare of persistent time, but the results are always disappointing. Still they keep checking.36

For Stella, there is a linkage between the “ephemeral quality of painting” and the “dull presence of our mortality.” That is, the fugitive nature of the artist’s work mirrors life’s transience, “the impending erasure of memory.” In one sense, negotiating this nature rests at the very heart of the artist’s calling.

As well as any, Stella’s own art showcased the pursuit of three primary, dynamically interconnected activities: the innovative manipulation of materials, the refinement of the artist’s marks and the subsequent generation of meaning (see fig. 8.3). From Monet’s impressionist daubs to Pollock’s pours and drips to the patina on an Anselm Kiefer sculpture or the craftsmanship of a Martin Puryear installation, the natural sequence from material making to making meaning is a common modernist refrain. Borrowing on existentialist language, these kinds of creative endeavors can be regarded as a kind of Tillichean quest to discover an “ultimate concern.”37

At this point, some comment about the artist’s persona seems fitting. Just as there is no acceptable way to describe the persona of all persons who are religiously inclined, neither is there one adequate means to characterize the artist’s nature. Nonetheless, in the broad sweep of history, artists have borne a variety of guises—the bohemian, the scoundrel, the dandy, the trickster, the genius, the prophet, the narcissist, the hero and the shaman. Belittled by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, but lauded by wealthy Italian patrons such as the Medici during the Renaissance, the artist, then, is heir to a checkered past. But no matter how one regards the standing of any particular artist, the modern reputation of artists is that they are the ones who rise up as a strident voice in the crowd, perform an unexpected gesture, pursue beauty, or hold out for greater wisdom and good that can only be realized by choosing the narrow way (Jesus) or heading down a road less traveled (Frost).

For believing persons, a second question follows: Does this description of the artist’s calling hold up as a Christian calling? I believe that it does. After all, Stella’s manner of thinking is aptly allied with biblical texts such as Job, Ecclesiastes and many of the psalms. I am not here attempting to describe Stella’s “religion,” since I know nothing of his personal convictions in this regard. My point is otherwise: from the brute and profane to the elegant and sublime, serious art either showcases or upholds our humanity.38 Whether one is caught up in the cosmic breadth of the biblical story or some other compelling narrative, the ephemeral nature of our lives is central to their telling. And here we return full circle to Stella’s insistence about the nature of painting. In pursuit of art or religion or both, we begin, as we must, by recognizing our finitude. In her recalibration of the world, the artist restores human proportion to the vast physical, intellectual and social space that each of us inhabits.

This leads to a third question, one frequently asked by art’s detractors: Is art necessary? The ready answer to their query is this: art is only necessary if our being human is necessary. We have already established that art confirms our humanity, but here we go further to insist that art’s existence is predicated on this humanity. And theologically speaking, we declare something more: art is manifest in the world because we are the imago Dei. It cannot be otherwise.

For Christian believers, then, a fourth question arises: Is it possible to make meaningful art in a post-Christian world? If a Christian worldview is now out of fashion, if this ancient intellectual framework has been displaced by secular ideologies, if God no longer establishes or animates reality, it can be argued that the table of the artist’s task has been entirely reset. But here caution is invited. Although this perspective is widely lauded, it is but one perspective. Alternatively, consider Madeleine L’Engle’s conviction concerning the interplay of art and faith: “To try to talk about art and about Christianity is for me one and the same thing, and it means attempting to share the meaning of my life, what gives it, for me, its tragedy and its glory.”39 L’Engle believed that art and Christianity lead to the same place: both aid us in our struggle to make sense of the “tragedy and glory” of life. In fact, we know more than we are able to express, and it is from this deep well of experience and being that the fullness of life emerges. To that end, the visual arts are a present help since aesthetic ideas are so often mediated to us as material forms. For artists of faith, then, the personal and interior aspects of knowing—everything from the sensate to the theological—can be negotiated, at least in part, in material terrain. For, like the gospel, art is incarnate.

Our fifth question and one of substantial interest to many is this: How shall we realize artistic success? My answer here is direct and oriented more toward performance than results. For Christians, it seems, the artist’s true calling begins at the place where the desire for fame recedes and then slips entirely away. Rare is the contemporary artist who will earn his keep by selling art. Fewer still will exhibit in prestigious galleries or museums. For most, being an artist in America holds no promise of financial return or cultural prestige. Admittedly, this is not a promising report.

Still, and following on the topic of success, one observation seems to hold: the artists whom most of us deem to be successful share a common trait—they do the work. At some point they set romantic ideas about being an artist to the side and commenced doing the artist’s work. Arriving at this place requires one to accept delayed gratification, the awkwardness that is sure to come from making bad art and the reality of negative cash flow. Pushing beyond distraction and discouragement, they accomplished something Herculean—they pushed beyond musing and imagining to establish regular studio practices, to take on habits of making. In the words of Karen Swallow Prior, these artists “clarified their telos.”40 Writes Madeleine L’Engle, “We must work every day, whether we feel like it or not, otherwise when it comes time to get out of the way and listen to the work, we will not be able to heed it.41

In the end, the contemporary artist is advised to shed vain imaginings about her “specialness” or “superiority” and direct her hands, heart and mind to the particular tasks she has been given or called to accomplish. Religious or not, the artist does so by faith, since she can have no confidence that what she has imagined and given herself to will take form.

Our sixth and final question is this: Having acknowledged that today’s world is broadly post-Christian, should Christians abandon their time-honored beliefs? Not at all! Biblical precedent confirms that the relative standing of Christianity when compared to other religions and ideologies—its rank in the polls, so to speak—has no particular bearing on the truthfulness of the Bible nor the compelling nature of the gospel. In fact, ancient Israel was a persecuted minority that struggled to survive amid powerful pagan tribes and empires. Similarly, the early church emerged beneath the cruel hand of Roman rule and was surrounded by a multiplicity of philosophies and sects and a competing pantheon of gods and goddesses. Where truth and revelation are concerned, popular opinion can have no standing. The reigning empire of Christendom might be a fixture of the past, but for those who believe, the Christ-life remains as vital, potent and compelling as ever. The reason for our hope is fixed and constant.

THE HOPE OF THE NEW

The God of the Bible is revealed to us as a covenant maker and covenant keeper, and orthodox Christian belief rests on the bedrock of God’s faithfulness. This is the central message of the beloved hymn “Great Is Thy Faithfulness,” penned by Thomas Chisholm in 1923:

Great is Thy faithfulness, O God my Father,

There is no shadow of turning with Thee;

Thou changest not, Thy compassions they fail not;

As Thou hast been, Thou forever wilt be.

A hallmark of evangelical Protestantism has been and continues to be its conviction that all true knowledge is rooted in the immutability of God’s character, that his character is revealed in the Bible and that it is foundational to all faith and practice. These convictions form the basis of the creeds it confesses, its confidence in the efficacy of Christ’s atonement for sin and its reason to hope for a heaven beyond this world. Throughout the twentieth century these biblical and theological convictions encountered unending and often vicious challenges, especially from cultural and intellectual elites. Understandably, the impulse of theological conservatives was to guard the gospel, keep the faith, hold their ground.

During these same decades, a radically different disposition was taking root in the secular world: modern art, philosophy and even theology set myth and superstition to the side to embrace what philosopher Charles Taylor terms a “disenchanted world.” At the center of this new ideology was an increasingly independent and liberal self. Robert Hughes’s description of modernism as the “shock of the new” is, therefore, an almost ideal summation of this movement, and to a substantial degree it continues to inform the unfolding aesthetic of contemporary art. From the advent of modernism onward, the pursuit of the new—achieving something that has “not been done”—would indelibly mark the art world aesthetic. It was believed that innovation, invention and experimentation would eradicate the cliché, overcome sentimentality and deliver authenticity.

Here again, the oppositional dispositions present throughout this book surface. On one hand, we observe conservative Christians vouchsafing the past and cherishing the “old, old story.” On the other, we note modernism’s strident entrance into contemporary culture as an emancipating force. It might seem that if one community sought to obey God, then the other cast its lot with rebellion and revolution. It is remarkable, is it not, to observe the degree to which the impulse to conserve and its resistance to change so easily sponsors the kind of reactionary posture exhibited by the religious right. Alternatively, it seems that invention, which begs for rule breaking and the testing of limits, becomes fertile ground for the radical ways of the left. In noting these trends, my purpose is decidedly apolitical. I want to point out the degree to which the penchant either to conserve or to invent conforms so easily to the mental models we adopt. Spelled out, this simple binary appears as follows: Christianity is conservative and reactionary | Modern art is liberal and revolutionary. Let’s explore the assets and deficits of each position a bit further.

The impulse to conserve is well justified. Most persons, religious or not, are inclined to preserve that which is good, true or beautiful. A conserving spirit (think of our museums and family archives) grounds us to reality and enables us to remain faithful to our story. In view of this, Christians in every age have been called to defend their faith, granting no quarter to heresy or false teaching. But in their pursuit of faithfulness, these same Christians have often succumbed to fear or entertained pride. That is, their foundational commitment to truth too often sponsored a spirit of moral and spiritual superiority and its overflow, judgment and haughtiness.

Our perennial fear of change—which seems to intensify over time—underestimates the dynamic nature of God’s creative and redemptive work. And so it follows that stasis, the negative stance of the positive desire to conserve, can resist divine change and frustrate the work of the Holy Spirit. Here the continual temptation for evangelicals is to go directly to glory without living for a season in this world. Marilynne Robinson cautions against this: “The great narrative, to which we as Christians are called to be faithful, begins at the beginning of things and ends at the end of things, and within the arc of it civilizations blossom and flourish, wither and perish.”42 In fact, change is normative and necessary, though not all change is good. For instance, when the systems in our body cease to function, death is near. Similarly, when spiritual life grows stagnant, when creative thought ceases and when institutional endeavors become gridlocked, the vitality of each is at risk. The cessation of change means certain death.

This understanding of change has direct bearing on the artist’s calling. Critic Vicki Goldberg puts it like this: “Artists are engines of invention.” Innovation is marrow in the creative bone, and at its best this kind of imaging enables us to meet the future. But the pursuit of innovation as an end—fomenting change simply to witness the thrill of disruption—can be foolhardy and even sinister. Novelty for novelty’s sake runs the risk of being little more than an adolescent effort to relieve boredom or redress dystopia. Consequently, the penchant that some have to reflexively privilege “the new” raises important moral and spiritual questions, especially when, in the aftermath of this perennial change and the spectacle that accompanies it, we are not left enlightened, but rather numb or dumb.

Christians dedicated to the visual arts must recognize the need both to conserve and to innovate. And here we are well served by an insight from Dorothy L. Sayers: “The artist does not recognise that the phrases of the creeds purport to be observations of fact about the creative mind as such, including his own; while the theologian, limiting the application of the phrases to the divine Maker, neglects to inquire of the artist what light he can throw upon them from his own immediate apprehension of truth.”43 Ideally the “creeds” and the “creative mind” will coexist in splendid, life-affirming synergy.

For faithful artists, these impulses are best married, conjoined. This is because hope, Christian hope, is dynamic, not static. The Spirit of Christ has been loosed on the world and never tires from the work of transformation. The movement and labor of God’s Spirit is fixed on healing, reformation, repair and resurrection—infusing light into our dark souls, imparting theocentric order to the farthest reaches of the universe. In the Christian frame, then, it is not merely the new that we seek but rather the redemption of all things, including women and men, body and soul. We long for nothing less than a final reversal of our misfortune, fear and every cause of anxious being. Marilynne Robinson writes, “The meteoric passage of humankind through cosmic history has left a brilliant trail. Call it history, call it culture. We came from somewhere and we are tending somewhere, and the spectacle is glorious and portentous.”44 This new day comes to us as a fresh, dew-laden morning, and it is the radical nature of the gospel of Jesus Christ that prepares us to receive it.

If the Christian story is true, then there will be signs both hidden and seen scattered all about. In fact, the plans for a “new heaven” and a “new earth” have already been laid (Rev 21:1). A day is coming when the refiner’s fire will separate dross from pure gold. Sheep will be sorted from goats. The nations will be judged, but they will also be healed. The secrets formerly seen through the screens of sign, symbol and code will become hyperreal. At last, all that has been unseen will be seen. This is why the whole of creation and we ourselves groan as we await the redemption of all things at the end of chronological time (Rom 8:19-23). This longing anticipates that great day when all things will be made new. For God declares, “I am making all things new” (Rev 21:5).

I suppose that most who have read this book will be persons on a journey with God and toward God. Many might be artists. To make progress on our way—to see clearly—the substantial underbrush in this thicket we call life must be cleared away. Gaining clarity of vision, seeing rightly, is the first task of every true vocation and the particular task of every artist. The prospect of facing the future might alternately fill us with deep dread or eager anticipation, and no measure of planning or divining can equip us to face tomorrow’s demand. Indeed, the heart of Christian religion is a decision to live by faith, to place oneself under the care of the only One who knows what the future holds.