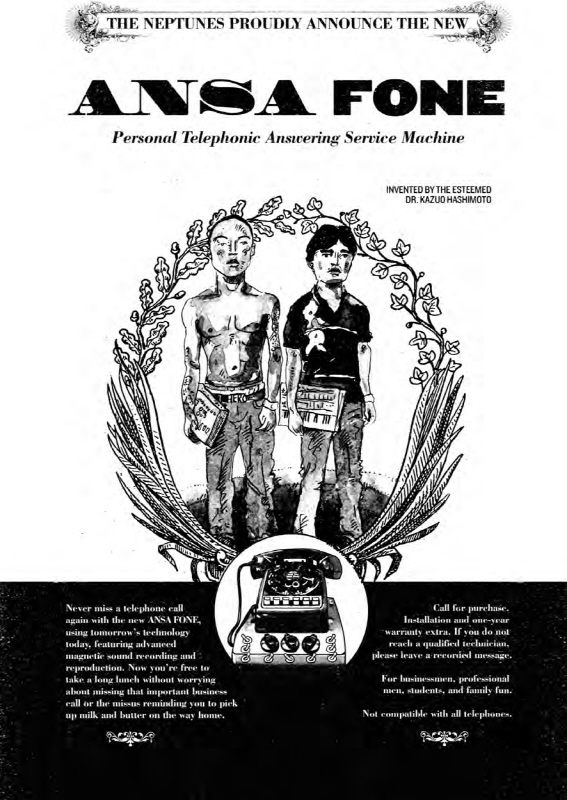

[ THE NEPTUNES ]

SCENE 1

When Esquire ran a special issue featuring the best and brightest ideas and minds in the country, the editorial board named the Neptunes—the production team of Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, responsible for hits by Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, and Snoop Dogg—as the most promising musicians of the moment. With Bill Clinton penning the introduction to the issue, the producers were in high-caliber company. So I called their publicist to schedule time with Pharrell. Below is the first of five interviews with him, all of which are included here in their entirety.

Hey, this is Neil Strauss from Esquire. Thanks for doing this.

PHARRELL: Hey, I’m having a house party. Can we reschedule this?

Sure, when do you want to—

PHARRELL: (Click.)

[Continued . . .]

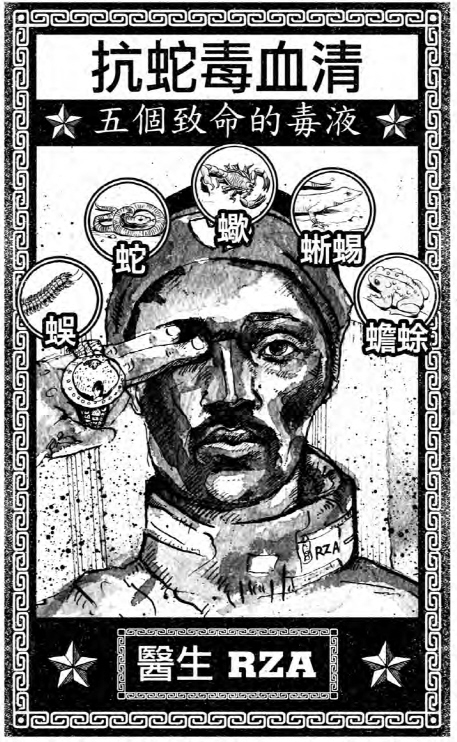

[ KORN ]

SCENE 1

It was supposed to be the biggest, most mainstream press exposure the hard rock band Korn had gotten to date: the cover of Spin magazine. Yet two weeks after the interview, the band’s management company, the Firm, called and offered me ten thousand dollars not to write the article.

Evidently Fieldy, the band’s bassist, had gotten into a fistfight with Spin’s creative director during the photo shoot and the band didn’t want to be on the cover anymore.

An hour later, an editor at Spin called and said the magazine was thinking of killing the story because the band had called another staffer at the photo shoot “a cunt.”

“That’s part of their charm,” I explained.

By that point, I’d spent enough time with these five misfits from Bakersfield, California, to see them piss off just about everybody they crossed paths with. At the Fuji Rock Festival in Tokyo, Fieldy picked a fight with a member of Primal Scream by repeatedly insisting, “You look like my uncle Bob.” An hour later, he was annoying Garbage singer Shirley Manson by repeatedly sticking a toy keychain in her face and setting off various sounds without a word of explanation. Meanwhile, Korn singer Jonathan Davis was yelling at drum-and-bass star Goldie, “Fuck you, dick!” And Junkie XL, a dance musician from Amsterdam, turned down dinner with Korn because he thought the band members were assholes.

But he was wrong: The guys in Korn aren’t assholes. They just want some love—and when they don’t get it, they act out. In his hotel room, raving drunk the night before the band’s Tokyo performance, Davis stood on a chair and explained.

JONATHAN DAVIS: We go to these goddamn festivals, and no fucking goddamn band will love us. We get no fucking love at all. It’s like we’re in our own little world. We’re not that goddamn scary. What the goddamn fuck? For once in my life, please love me: I’m in Korn.

Well, you guys weren’t out there making friends today.

DAVIS: We’re nothing like that, man.

Leaps off chair.

Like what?

DAVIS: Any of that shit!

Any of what shit?

DAVIS: Any shit that’s out there. There’s so much rehashed shit. You see it around us at the festival: Musicians fucking hate us. Fucking hate us!

Why is that so important?

DAVIS: I don’t know. What can you call it?

Call what?

DAVIS: [Our] music. What can you call it? It’s like the Clash: What the fuck can you call the Clash? Fucking punk, pop, reggae? That’s a great band.

People call you heavy.

DAVIS: They do?

I’m talking about your music.

DAVIS: Yeah, we just want to be heavy. That’s what it is. All we want to do is bring heavy back into rock and roll, because goddamned Ben Folds Five sucks. It’s fucking Cheers music. With us, it’s fucking special. We’re all completely different.* I’m a sissy, basically. Fieldy’s hip-hop, Head and Munky are Head and Munky, and David [Silveria]’s got tits † but he’s a great drummer. All we have in common is that we’re all freaks, we’re all fucked up, and we’re all on drugs.

Later that night, Davis plays a track from his new album, then explains . . .

DAVIS: That song’s about how I thought I’d become a rock star and not get picked on anymore, but my band still calls me a fag.

I’ve noticed that.

DAVIS: Everyone thinks I’m queer (sighs). And I kind of am—except for the dick part.

At two a.m. the phone rings in my hotel room.

Hello.

DAVIS: Know what I said about us being outsiders? Forget it.

Why’s that?

DAVIS: Prodigy walked up to us.

Great.

DAVIS: We were downstairs drinking, and all of them were there. And there was skinny model ass everywhere.

Were the models coming up to you?

DAVIS: No, not at all.

But Prodigy were.

DAVIS: They were like, “What’s up, guys?”

Good for you.

DAVIS: I think it’s coming around, man. Wanna come upstairs and cuddle?

I’m wiped. Let’s talk after the show tomorrow.

DAVIS: Yeah, you’re probably right. [My bodyguard] Loc told me I can’t do coke tonight because I have to work tomorrow.

[Continued . . .]

* Korn fun facts learned in Tokyo: Guitarist Munky wet his pants onstage once, Fieldy won’t touch stairway handrails because he’s afraid of germs, second guitarist Head drinks six-packs of beer alone in his bathtub, and Davis refuses to touch or lick female genitalia.

† Most people would call them pecs.

[ THE NEPTUNES ]

SCENE 2

Three days later . . .

Thanks for rescheduling this.

PHARRELL: Sure, man.

One thing that sets you apart from other producers is that you don’t differentiate between genres—

PHARRELL: Dude, can I tell you something? I really don’t give a fuck about different styles. Music is music. In the eighties, that’s the way it was. On the big black station here in Virginia—we would listen to 103 Jamz, which I would love for you to print, and that station would play all kinds of shit.

What artists have you been working with lately?

PHARRELL: First, there’s Mystikal. I would love to just go to the dustiest part of Georgia—even though he’s from St. Louis.* I would love to go to a desperate area, with no people almost, very country, and just record his album in a shack. And then . . . Actually, I’m about to go out now and get some chicken. So can I just call you from the road?

Okay, but make sure you call this time.

PHARRELL: Promise.

[Continued . . .]

* Actually the rapper is from New Orleans, though the collaboration was postponed when Mystikal was imprisoned the following year for sexual battery of his hairdresser.

[ CHER ]

SCENE 1

Sometimes stories collide. For example, you’re on the phone with Cher for the New York Times while you’re at guitarist Dave Navarro’s house writing a book with him.

Do you mind talking to Dave Navarro? He’s with me right now and wants to say hi before I let you go.

CHER: Sure, I’d love to.

DAVE NAVARRO: How are you?

CHER: I’m good.

NAVARRO: I just couldn’t allow this phone call to be made from my house and not get in and say hello.

CHER: Oh, I’m so happy that you did. My son has been a huge fan of yours for such a long time.

NAVARRO: Is that right? I’ve met him several times.

CHER: Yeah, he was little when you first met him. I mean, well, he’s twenty-three now, but he’s been a fan of yours from the get-go. He’s struggling, but that’s good.

You need to struggle if you’re going to be in music because you’re going to struggle sometime one way or another.

NAVARRO: Oh God, yeah, ain’t that the truth. But he seems to be doing well.

CHER: Yeah, I think he needs to stay on the straight path. But he’s a good boy inside. It comes easy to him because he’s really talented, but he doesn’t know that it’s not enough.

NAVARRO: I know. That was a mistake of mine.

CHER: I hope he gets through it.

NAVARRO: I do, too. I didn’t know he was having that hard of a time.

CHER: Yeah, he is, kind of. He’s really trying to address it and yet he doesn’t. You know how to get anything done, you have to say, “Yeah, it’s a fucking problem.” He’s at that place where he wishes that it wasn’t a problem.

NAVARRO: To run to a self-help group at that age can be really traumatic. It’s almost worse than what any drug can do to you.

CHER: Yeah, you know, it’s in this place where I just don’t know which way to turn.

NAVARRO: You can’t force him. He’s got to do it himself.

CHER: So I’m just laying back but, boy, I’m not a good layer-backer when it comes to my kids, and especially to him.

NAVARRO: I don’t think any parent would be. My father wasn’t. I lost my mom when I was very young and I was a heroin addict for a lot of years. And my dad, as much as he knew he had to sit still and wait, couldn’t stand keeping quiet.

CHER: I just don’t want to see my son turn out like his father, because his father was a really great, fabulous, wonderful, funny, special man. And finally the drugs just became him. He wasn’t himself. He’s been taking them for so long that there’s just nothing left of him.

NAVARRO: I’ve met him a few times, too, when I was trying out those rooms for a while and . . .

CHER: Board those guys up and just move on.

NAVARRO: I know, you kind of have to, huh? There’s only so much you can do and—well, I tell you, I appreciate it so much to say hello, and I’m just a great admirer myself so . . .

CHER: Thank you. Have a really good time with your life and your music.

NAVARRO: Thanks very much. I’m really excited. I’m just now doing something by myself and it’s the first time I’ve really been able to do anything like that.

CHER: Great. You know what, maybe when I come home we’ll get together.

NAVARRO: I would love that so much.

CHER: Okay, great. Am I going to talk to the boy again that I was just talking to?

NAVARRO: Would you like to? It’s up to you.

CHER: Sure, I want to say good-bye.

Hi.

CHER: Hi. He sounds so sweet, doesn’t he?

He’s very nice.

CHER: Well, I really wish him well, because he sounds really, really good. Boy, you know, I gotta tell you something: If this business doesn’t fucking kill you, then you can just come back and hopefully be the best person you’re ever going to be, because it’s the only business that eats its young.

[Continued . . .]

[ JOSH CLAYTON-FELT ]

The following is a cautionary story that shows just how heartless record labels can be.

It begins in 1996, when Josh Clayton-Felt, who had a couple minor hits with his band School of Fish, submitted his second solo album to A&M Records. The label sent him back to the studio to record more songs, and then sat on the album for eight months, promising to release it soon.

Then, in a surprise announcement, A&M was bought as part of a corporate merger and collapsed into the Universal Music Group. Clayton-Felt was one of some 250 artists dropped in the downsizing afterward. This would have been a relief for him, but the label refused to give Clayton-Felt his music back.

Any progress in getting the rights to your music?

JOSH CLAYTON-FELT: I’ve spent the last four months saying to them, “I know I was dropped, but can I have the record back? Or can I release it independently myself and give you a percentage of the sales?” But they said that basically the only way they’ll release it is if I’m on a major label and the label pays a lot of money to Universal for the record. But I don’t want to do that: I just feel like it puts me in a bad place creatively.

What about just re-recording the songs and putting them out yourself?

CLAYTON-FELT: I can’t do that, either. What I didn’t know is that they own the songs I turned in. So not only are they not willing to give the record back, but they won’t let me re-record the songs. According to them, I can’t re-record them for five years.

Why do you think they’re doing this? It’s not like they’re making money off the music.

CLAYTON-FELT: I tried to figure out why they want to do this. I think they know the power of the Internet and the artist, and maybe by taking 250 artists and shelving them, they’re eliminating the competition.*

So what are you going to do?

CLAYTON-FELT: It’s tough. I even went to the point of thinking: What if I changed my name, or had a band instead, or wore a dress and played the songs? But from what I understand, there are probably a hundred artists who have albums shelved because of the merger. My idea is to find these artists and do an album where I can’t record my song but Joe or whoever can, and Joe can’t record his song but Paul can. We’d each put in our best song and give it to someone else. It would be making a statement about the whole being more important than our individual needs. If this can be turned into something positive, I’d be happy.

I think a lot of artists would just give up and record new songs in your situation.

CLAYTON-FELT: I’m not giving up on these songs. I love them. Maybe the record company will see the article and it will put them more in a place of their heart than their wallet.

Unfortunately, the story didn’t sway Universal Music Group. So Clayton-Felt decided to go into the studio and re-record the music anyway. He explained in an e-mail that at least this way he could make the album he always wanted without executive meddling, and maybe Universal would allow him to release it before the five years were up.

He finished recording on December tenth, 1999—almost four years after he turned the original album in—and told friends that it was now, finally, perfect. But then something unexpected happened: The following day, he developed severe back pain, which he thought was due to stress. When he went to a hospital to have it looked into, he was told he had testicular cancer.

When Universal heard about his illness in early January, the label finally gave him and his family control of the record. But it was too late: By then, Clayton-Felt was in a coma. At 4: 45 in the morning of January nineteenth, he passed away at the age of thirty-two.

But death was not the end of the story of Clayton-Felt’s music.

LAURA CLAYTON BAKER [his sister]: We worked on getting the record out for two years. There were just constantly frustrations: waiting for the paperwork, waiting for photographs, getting the artwork done, scheduling. Everything seemed to take so long because he wasn’t there to help make the decisions.

STEVEN BAKER [his brother-in-law and president of DreamWorks Records]: A lot of people at DreamWorks came through and listened to the songs and liked them, and have had a great love and respect for the record. So I was able to get the label to put it out. The deal with DreamWorks is that they’re pressing and distributing the record, and our family is paying for marketing and publicity.

Several former employees of A&M who used to work with Clayton-Felt volunteered to do the marketing and publicity for free. In the meantime, his mother coordinated a network of fans in different cities to help with local promotion.

MARILYN CLAYTON-FELT [his mother]: He said that his work wasn’t finished here, so I tried to finish it. Well, finish is too final. I tried to bring it to the world.

* Speaking on condition of anonymity, an executive at Universal offered a different reason: “Money’s money. We aren’t big enough to handle settlements for all these acts.” Meaning, presumably, that the label didn’t want to pay the attorney fees involved in returning the music to the artists.

[ BACKSTREET BOYS ]

SCENE 1

The Backstreet Boys have sold more than seventy-five million albums around the world, a number that few pop acts have surpassed. In their prime, they were a pop juggernaut, breathing new life into MTV, the record business, children’s radio, and teen magazines.

But along the way, a very similar band with the same management company and the same songwriting and production team surpassed them in popularity: ’N Sync. As ’N Sync’s star rose, the Backstreet Boys seemed to disappear. After much coaxing, Kevin Richardson, the oldest member of the band, agreed to sit down and discuss life behind the scenes as a pop phenomenon—and what happens when five young men put to work as pop puppets grow up and develop minds of their own.

There’s a lot of pressure on you for this next record. Do you feel it’s a make-it-or-break-it moment?

KEVIN RICHARDSON: Yeah, I feel like it’s a very crucial record in our career. In April, we just had our nine-year anniversary. In nine years, we’ve had five albums, including the greatest hits album. So I just want to put out something I’m proud of, and happy and excited about. The last record, and I’m not whining or complaining or blaming anyone because it sold a lot of copies, but for me personally, creatively, I wasn’t happy with it.

Why not?

RICHARDSON: I wanted to experiment more. I felt like we should have.

Experiment in what way?

RICHARDSON: Just working with different people—exploring, taking chances, taking control, and trusting in our gut. But, you know, it’s not always easy. There was all this pressure and fear from our label and our management company at the time. And I’m like, “Guys, we’ve got millions of fans all over the world. If we make great music, that’s all that matters.”

So tell me one of your ideas they wouldn’t use.

RICHARDSON: You know, we’ve thrown all kinds of ideas around. We thought about having an album that was about different styles and flavors of pop. Like almost a compilation, but it would be all us doing the music and a picture of like a lollipop on the front with the words, “Suck on this.”

[Continued . . .]

[ BILLY JOEL ]

Backstage at a Person of the Year dinner produced by the organization that runs the Grammys, Billy Joel sat in a large armchair, sweating after his speech under the hot lights of the stage. His acceptance speech began with him saying that Sting, who was trying to save the “fricking rainforests,” was probably more worthy of the award. He spent the remainder of the speech addressing an important issue pertaining to artists of his caliber: asking industry members in the audience to set him up on a date with Nicole Kidman.

Is your record company upset that you haven’t recorded anything new in so long?

BILLY JOEL: I’m an artist who hasn’t handed in an album since 1993, and my record contract says I’m supposed to hand in albums. Now you can’t get blood from a stone, and the record company understands that. I think people have all these assumptions about what kind of power a record company has over an artist. I never had a bad relationship with Columbia Records. I was fortunate enough to have come up in the early seventies, when there was freeform radio and I had album cuts played and I wore whatever dopey clothes I wore and I had bad hair and the whole thing.

But you were taken advantage of a lot back then, too.

JOEL: I have to audit my record companies all the time. I’ve had managers who’ve taken me to the cleaners. I’ve been fleeced numerous times. There are certain promoters who were less than aboveboard. I was with a guy named Artie Ripp who was taking a piece of the action from me for twenty years, and that’s not right. I think it’s time for artists to climb out of the ivory tower, to stop living in a dream world, and to come buy groceries with everybody else and find out how the rest of the world lives.

In the sense of getting involved with the business side of things?

JOEL: It’s a job. And if you don’t see it as a job, then you’re kidding yourself. There’s a lot of work that goes on underneath the surface of this tip of the iceberg called the star. Most of it is promotion, marketing, politics, business, legal, and accounting. It’s the music business. It’s a business, not the Boy Scouts.

Some people would respond that artists should just focus on making music.

JOEL: I, for a long time, did not want to face up to the fact that there was capitalism involved in music. I thought that prostituted the art. “Oh my God, there’s money. I’m not doing this for money. I’m doing this for the art.” Well, I found out there are a lot of other people perfectly willing to take that money.

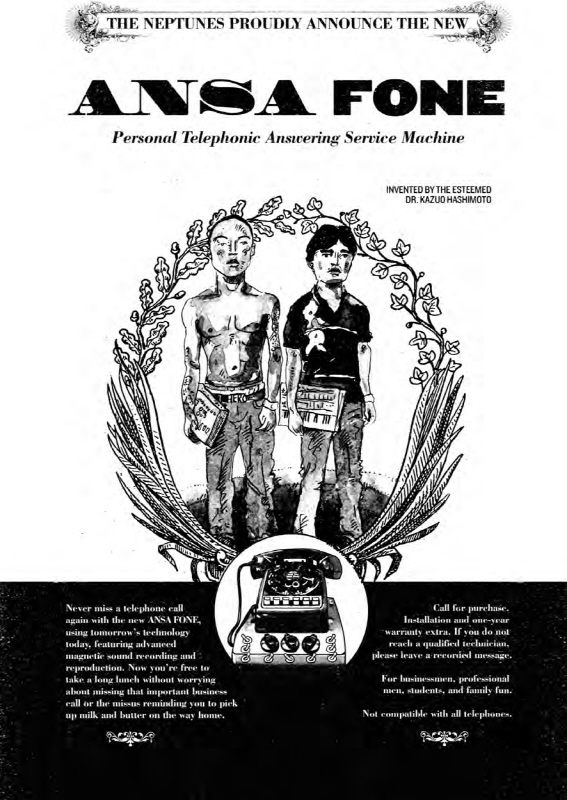

[ WU-TANG CLAN ]

SCENE 1

I first met the Wu-Tang Clan in a loft in the meat-packing district of Manhattan, where the rappers were watching a rough cut of a new video and reading books like The Mind and The Prophet. The RZA, the group’s producer and mastermind, pulled me into a garbage-strewn stairwell so we could talk in private—and so he could smoke a hand-rolled cigarette. Maybe it was laced with hash; maybe it was laced with PCP; maybe it was laced with both; or maybe it was just tobacco. We will never know.

The conversation began with an in-depth analysis of his cryptic lyrics . . .

How about the [lyric], “I stand close to walls, like number four the lizard”?

RZA: That’s only for the hardcore fan, right there. There’s a movie called the Five Deadly Venoms. You ever heard of it?

Is Woody Allen in it?

RZA: No.

Then I haven’t heard of it.

RZA: It’s phat. You should see it. So there’s five deadly venoms in it, and number four is the lizard. And they talk about how he climbs walls. That’s my style, staying close to walls.

In “Bells of War,” you say, “Illegible, every egg ain’t edible.” And then later, “Got to catch this paper to buy Shaquasia a glacier / Melchizedek a skyscraper.”

RZA: You can take every egg ain’t edible in a lot of different ways: from the female, from the biblical, from the idea that everything that you see ain’t good for you. That’s like universal knowledge. The other lyrics are about my children. See, I got to make this money to buy her a whole glacier. I want to buy my son a whole skyscraper. I gotta make a buck.

You have two kids?

RZA: I don’t even know how many babies I got.

You must know. Wouldn’t all their mothers be hitting you up for money?

RZA: That’s what the money I make is for anyway. I don’t like to talk about babies. Say if I’ve got five babies with five women, I’m working for them. I’m not working for me. [. . .]

Did you make any money by adding America Online software to the interactive CD that comes with Wu-Tang Forever?

RZA: I didn’t make no money from that. I don’t know who did, but I didn’t.

So what is—

RZA: Hold on, do you think there’s money to be made from that?

I think if America Online is going to be making money by getting new subscribers from people who bought the Wu-Tang CD, then you should get something.

RZA: I didn’t go that deep into it. That’s good information. I’ll investigate that.

So what’s your ultimate plan? Where are you trying to get to with your music now?

RZA: I might be backing out of it. My little brother’s making tracks now. And there’s about twenty-one mothers trying to make my beats, so I don’t got to make beats no more.

What would you do?

RZA: When I complete this, I’m going to be a doctor. That’s my love right there, my lifetime goal. I’ve got a few stumbling blocks I’ve got to overcome. But I’m going to make something special for the planet. It’s going to be something that’s going to remain. There are 109 elements—everything you see is composed of them. I’m going to put some of that shit together. I’m studying it all—mental, physical, chemical. I’m studying the body, circulation, tai chi, all that.

What’s your specialty going to be?

RZA: My specialty’s going to be peace. I’m going to do it, man.

[Continued . . .]

[ CURTIS MAYFIELD ]

Curtis Mayfield is responsible for some of the most seminal soul, funk, and inspirational music of all time, from his anthem with the Impressions “People Get Ready” to the theme from Superfly to the samples that have fueled over a hundred R&B and hip-hop songs. But in 1990, while preparing for a concert in Brooklyn, Mayfield was struck by a falling lighting scaffold that paralyzed him from the neck down.

In your music, you sing about peace and how there are better years coming. Now, when you hear those songs twenty-five years later, do you feel peace and better years have come?

CURTIS MAYFIELD: Well, I believe never lose hope. Never lose faith in your dreams. In spite of this world, there is still a whole lotta good people in it—and I must believe that. So I’ll never give up and just lose total hope for mankind itself. And I’m a rather pessimistic fellow (laughs). But I’m optimistic about people and I must be. I mean, especially in my shape today. If it weren’t for a lot of good, good people about, I’d be in bad shape. So just keep the faith. That’s what [congressman] Adam Clayton Powell used to say.

I suppose some things have gotten better and other things have gotten worse. I guess that’s how it always works.

MAYFIELD: Ain’t that life? But somehow we still manage and somehow, if you look for it, you can still live for happiness. It might be a little harder trying to achieve, but you don’t give up, you know. Can’t give up to these losers, man. In spite of these people that drag you down and create crime and hardship, you gotta believe that people are better than that.

Has the accident changed any of your ideas about life or what we’re supposed to do with the time we’re given?

MAYFIELD: Well, no, nothing’s changed too much. I’m the same person. I just happen to be paralyzed. Of course, you have to deal with the complications of being in this particular order, but I still carry my spirits as high as I can. If anything, after the accident and seeing beautiful people of all colors, races, and creeds come to my aid and having their love, respect, and especially prayers, I must believe in mankind even more.

Are you still able to perform?

MAYFIELD: Oh, I have no plans of performing again. Being a quadriplegic, it will be just a little too testy. It’s really always a life-and-death situation—almost every minute of the day. Then there’s the cost of just getting me around. You know, when I get up and go anywhere, it can cost me from ten to twenty thousand dollars between making travel arrangements, taking along a nurse, getting baths, and all the other stuff I need just to survive. So performing is out of the question.

On one hand, it’s been great to see your music celebrated with three new compilations and two tribute records, but on the other hand, do you kind of wish that people were doing it anyway before the accident?

MAYFIELD: A lot of people say that I didn’t get the credit I deserved in my day, but I was never overly saturated with success either. I may not have been making music in these times where they’re making twenty million dollars a year, but somehow I managed to survive. I raised all my children and I’m living a decent life. I’m a great believer in the saying, “It may not come when you want it to, but it’s right on time.”

What do you think is the most important thing you’ve taught your children?

MAYFIELD: Live by example.

Shortly after this interview, Mayfield’s right leg was amputated because of complications from diabetes, which he developed due to the injury. He died a year later at the North Fulton Regional Hospital in Roswell, Georgia. He was fifty-seven years old.

[ BACKSTREET BOYS ]

SCENE 2

Tell me if you agree with this: You’re human beings who some people just see as cash cows, right?

KEVIN RICHARDSON: Mm-hmm.

And because of that, the corporations that release your music are so worried about their bottom line that they’re not always going to do what’s best for the group.

RICHARDSON: I mean, when you have the level of success that we’ve had, there are a lot of expectations and responsibilities that are put on you. And with all of the business coming in, it blocks the artistry.

So maybe [your second management company] the Firm was the right place when you started there, but—

RICHARDSON: When Millennium came out, they were the right place. We were all so depressed and so sad and so tired of fighting everybody. We were dealing with lawsuits and fighting our original management company—and the managers locking our production equipment up, our stage, everything.

They locked up your equipment?

RICHARDSON: Yeah, our past manager. We were trying to get out of management contracts. We gave them an ultimatum and we had attorneys give them notice. And they locked our production equipment and stage and everything up and said, “You guys are supposed to do a tour, but you’re not getting your equipment.”

And you wanted to leave the contract because—

RICHARDSON: Our contracts were just exploiting us. We were being taken advantage of. And there’s the fact that they were managing us and then they signed ’N Sync, and we thought it was a conflict of interest.* Again, we have nothing against the guys in ’N Sync. They’re talented and we respect them, but they were directing them to work with all the writers and producers that we worked with. And they were using them against us, saying, “Oh, if you guys don’t do this gig, we’ll just book ’N Sync.”

I talked to your former manager, and he said that Disney had wanted to broadcast a Backstreet Boys concert special, but you guys turned it down and so he gave it to ’N Sync instead. And that special is what really started their career. Is that valid?

RICHARDSON: Yeah, we passed on that show because we wanted to spend time with our families at Christmas. It was either Thanksgiving or Christmas and we just came off the road in Europe, and that opened the door for them. But they worked hard. They deserved it. Everybody wants to pit us against each other. Everybody wants to say that—not everybody, but a lot of people say, “Oh, they took the crown,” or whatever. Like there was a crown.

So how did you get your equipment and stage back from your old manager?

RICHARDSON: We basically settled. We left them and the Firm rescued us. I’m grateful for that. At that time, they had Korn and Limp Bizkit, and they were a smaller company. But now they’ve built a huge powerful company and they’re good people. Please make sure you reflect that in the interview. I don’t want to bag on them, but this past year, some bad decisions were made and some bad advice was given.

Like when your tour was sold to Clear Channel † for a hundred million dollars—

RICHARDSON: Big mistake.

Big mistake?

RICHARDSON: We lost control of our ticket prices. Big mistake. We alienated some of our fans who couldn’t afford to come to the show. Big mistake.

So why did you do it?

RICHARDSON: When people were throwing that big number on the table, it was tempting. But we asked questions. We asked about ticket sales. We asked about the control aspect. And we were told not to worry. And it hurt us. We lost control—and we were advised to do that.

So what were the pros of doing that?

RICHARDSON: The pros of doing that was a hundred million dollar paycheck.

That’s a good pro.

RICHARDSON: I’m gonna tell you what happened. We made a deal with Clear Channel for a hundred million, right? We put a production together to play in arenas and then expand to go into stadiums. We spent that money—a lot of money. Well, then the economy dipped. And also, to be honest, when our managers and we saw the ’N Sync ticket sales not doing very well in stadiums—which, by the way, ’N Sync put their tickets on sale purposely right before ours, which is—

Which is capitalism.

RICHARDSON: Well, the thing about this I want to make clear is that we have nothing against those guys. We respect them. They’re very talented and they work their asses off.

I’m sure it wasn’t the band’s decision.

RICHARDSON: I mean, they hadn’t even put out a single yet. And the purpose was to beat us to the punch, which is fair game. It’s tactical. But once we saw their tickets weren’t selling very well and then the economy took a big hit, we were like, “You know what? We shouldn’t play stadiums.” I’d rather not play a sixty-thousand-seat stadium with thirty thousand people in it. So we all took a hit there. When the tickets don’t sell, somebody’s gonna have to cough it up.

Do you know who coughed it up? The House of Blues did, because the Firm talked them into giving the Mary J. Blige tour to Clear Channel to compensate for the money they lost on your tour.‡ Did you know that?

RICHARDSON: No, I didn’t. That’s . . . that’s . . . wow.

But in the end, you were the third top grossing tour of last year, so I still think it was—

RICHARDSON: No, it wasn’t safe. It wasn’t safe. And that’s one of the reasons we’re not with the Firm now.

Hang on, I got to go to the restroom.

[Continued . . .]

* Lou Pearlman, the Florida aviation entrepreneur who created both bands, responded: “The Backstreet Boys got so big, they got tired. And after a while, it became not about managing them but reasoning with them.”

† Clear Channel Entertainment was a concert promotion company that bought the rights to the entire Backstreet Boys tour.

‡ Mary J. Blige was one of the Firm’s other management clients. And the House of Blues and Clear Channel Entertainment were rival concert promoters.

[ JOHNNY STAATS ]

In order to interview one of country music’s greatest mandolinists, Johnny Staats, I needed to get permission from his manager—not his music manager, but the manager of the UPS shipping facility where he worked as a driver. Even though Staats had recently signed a major-label record deal through Time Warner—an extremely rare feat for a bluegrass picker—he decided not to give up his day job in West Virginia. So his boss gave me permission to ride along in uniform with Staats as he ran his UPS rounds on a cold, snowy afternoon.

“I’d sure hate to lose him as a driver,” said Doug Adams, Staats’s supervisor. “But I don’t know why a man with those talents continues working here. I guess it’s the security.”

So what are you going to do if your record company wants you to tour?

JOHNY STAATS: I’ve saved up all my vacation days for concerts, but I reckon I can’t tour. I have a wife and two kids, so I’m kind of stuck between a rock and a hard place. This job is real good money and the music business is shaky. One minute you’re living on steak; the next minute you’re living on beans.

Have you ever thought of moving to Nashville to help your career?

STAATS: If I moved to Nashville, I’d have to leave the country life. I’m just an old country boy: I love to pick and hunt coons. (He pulls up to a dilapidated red house and inspects it.) These kind of calls right here are where you have to watch out for Fido. If there’s pee on the porch, that’s a warning sign for me.

He leaves a package behind a shovel on the porch, then walks briskly along the icy path back to his truck.

How long do you work each day?

STAATS: On a normal day, I work ten to eleven hours. I worked part-time at first for UPS, and the way I made extra money was in music contests. I learned to play everything I could find: mandolin, fiddle, guitar. At Vandalia, I came in first on guitar, first in mandolin, and third in fiddle.* That was a good payday. I made twelve hundred dollars just in contest money. I was the West Virginia mandolin champion three times. It would’ve been four consecutive years, but I had to work one year and couldn’t get off.

How often do you practice?

STAATS: I used to practice a lot. In high school, the only thing I wanted to do was to play music. I’d practice seven to eight hours a day. I wasn’t interested in football, basketball, nothing. I’ve played so long before I’ve seen blood come out from under my fingernails, seeping out the end of it (sighs). I miss having all that time to practice now.

Many a day, I’ll take my mandolin with me, park the UPS truck in an old holler, and spend my lunch hour practicing. I’ve had people come up and knock on the door of the truck, wondering what that music was coming from inside.

He pulls up at an insurance office and walks inside to deliver a package.

Do you have any musical influences outside of bluegrass?

STAATS: Do you like classical? I listen to Mozart and Beethoven. Them’s what I call geniuses. Mozart would play four songs in one composition. That’s how I win the contests: I’ll play a bunch of different songs and styles, just to show them I can do anything.

He flirts with the secretary, hands her a package, then returns to the truck.

What would you do if you made enough money off your new album to live on?

STAATS: I don’t even know how I’d react if I ever made enough money as a musician to leave this job, because I’m so used to going to work. Boom! It would be a weird way of life when you’re not told to be here or deliver this package. The music business isn’t the real world.

(He displays the palms of his hands. They are caked black with dirt.) This right here is the real world. I’ve washed them three times today and the dirt still won’t come off.

True to his word, Staats kept his job and didn’t tour when his CD came out, though he did open a concert for the Dave Matthews Band. When I checked in with him a year later, he was working on his second CD during lunch breaks and after work, and preparing to perform with the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra. He was eventually dropped from the major label that signed him.

* The Vandalia Gathering, West Virginia’s annual heritage festival, was where Staats was discovered by Ron Sowell, musical director for Mountain Stage, a live concert broadcast on National Public Radio. “I pride myself on knowing the West Virginia scene, and I’d never heard of Johnny Staats before,” Sowell recalled.

“It was like he materialized. He played as fast as any human can play mandolin, but every note was articulated and under control.”

[ JONI MITCHELL ]

Joni Mitchell has been called the most influential female singer-songwriter of the twentieth century and has received just about every award a musician can, including at least nine Grammys and her face on a postage stamp. When the rest of the New York Times pop music critics and I selected the twenty-five most significant albums of the twentieth century, Mitchell’s Blue was on that list. Those who saw her perform in the late sixties and early seventies were awestruck, describing her as unearthly and angelic. So while spending three days talking with her over games of pool in Hollywood and meals in Brentwood, I was surprised to discover that gratitude and humility were not among her strong points.

Here’s what she had to say about . . .

. . . her songwriting.

I mean, there’s layers and layers to this song. The lyrics have a lot of symbolic depth, like the Bible.

. . . producing.

I don’t like the title producer. Mozart didn’t have one.

. . . her most famous song, “Big Yellow Taxi.” It’s a nursery rhyme. Of all the creations that are there, if you reduce it to this thing, it’s a tragedy.

. . . her record company. The record company has sat on this album, but sitting on me a little bit is not a bad idea, just to make it more timely. Because sometimes I’m too far ahead and people aren’t ready for it yet.

. . . being an opening act.

Bob Dylan is the only artist I open to. Period. Or Miles [Davis]. But Miles is gone.

. . . gender.

One guy came up to me and said, “You’re the best female singer-songwriter in the world.” This was some years ago, and I laughed. He thought I was being modest. But I was thinking, “What do you mean female? That’s like saying, ‘You’re the best Negro.’ ”

. . . astrology.

My daughter is a Pisces. She’s the day of the explorer. I’m the day of the discoverer.

She’s a natural follower. I’m a natural leader. I can’t help it. The stars put me there.

. . . her Grammy, Billboard, and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame awards.

Dubious honors. They knew that they had to do it, but they—at least the speechmakers—weren’t quite sure what to illuminate in the work.

. . . charity.

After Billboard honored me, all of a sudden VH1, who wouldn’t play my videos, decided to honor me, which means they get a free concert out of me. Then they hand me a check for my favorite charity, they take it away, and they get the tax write-off. So I refused to do it.

. . . a two-year-old article on her in the New York Times.

The guy was a bad observer, even down to what I was wearing. There were seven errors of observation in the piece.

. . . all of the above.

You think I got a trap mind or something? I guess I do. Yeah, I’m sensitive (pauses). I’m not a pitiable creature. It’s just that I suffer very eloquently.

[ JAY LENO ]

Shortly before what was supposed to be his last performance on The Tonight Show before handing the reins to the younger Conan O’Brien, Jay Leno, wearing an over-washed blue button-down shirt and faded jeans, sat down in the show’s green room to discuss leaving behind his legacy of 3,756 shows. Here are some choice excerpts.

Has there ever been a time where you showed up at the studio and you just didn’t want to do the show?

JAY LENO: I would like to say yes, but I have to say no. I mean, that’s what the job is. I’m a great believer in low self-esteem. The only people that have high self-esteem are criminals and actors.

I remember interviewing Joni Mitchell, and everyone was giving her all these awards and she was so ungrateful.

LENO: I love it when stars go, “Two hundred and fifty thousand dollars a week? I’m not working for that!” A million a month and you’re insulted—really? You don’t think you can be replaced?

I can’t say I ever get like that. It always makes me laugh when people say, “Oh, Jay was exhausted.” [Comedian] Alan King always used to say that exhaustion is a rich man’s disease. You know, if a coal miner says to his boss, “I’m exhausted,” the boss goes, “Get back to work!”

Do you ever have a distaste for someone you’re talking to, and you have to keep it in check while interviewing that person?

LENO: Well, yeah, that happens a lot. You know, it’s not a bully pulpit—I mean, with the exception of O.J. and those kinds of guests. But then there are guests who you don’t agree with politically, but you figure, let’s have them on. I remember I had Ann Coulter on the show. In my mind, because of the nature of what I do, I thought, “Well, she’s a biting satirist. This is sharp commentary that I don’t agree with, but I can see the wit in it.” And then when she was here, I walked out to do the warm up and I saw this kind of white-shirt-red-tie brigade in the audience. And everything she said, they hooted and cheered to the point where it was distracting. I thought to myself, “Well, maybe she really does believe all this crap.” I didn’t handle that one well.*

A lot of people say that the secret to succeeding in show business is just showing up on time.

LENO: In show business, if you can physically make it to the stage for seven years, you’ll always work. Most people can’t do that. It’s cocaine, you’re too straight, you’re too gay, you’re too whatever. I see a lot of comics after five or six years honing an act, they begin to hate it and they resent the audience laughing at them. Nobody was funnier than Sam Kinison with that high-energy scream. But it got to the point where it’s cocaine and guns, and now you’re going 120 miles an hour in the street and—Boom! Boom!—he didn’t make it to seven years. If you can make it through the seven, you’re okay.

When it was decided five years ago that Conan O’Brien would take over the show, was it weird for you to know you were going to be replaced?

LENO: You know, taking over these shows is like tsarist Russia. There’s too much bloodshed and anger. So I said, “Look, this is fine. Let’s see what happens.” Because back then, I thought, “Pssh, five years—that’ll never come!” But when it happened, I still liked doing this. And ABC and Fox and everybody else seemed interested.

Why didn’t you consider going elsewhere?

LENO: You know, showbiz is not that hard. People make it extremely difficult. The problem starts when you have to have all the money. I don’t need all the money. It’s just my wife and me. I don’t have an agent. I don’t have a manager. I’ve said this a million times and it’s cliché, but I’ve never touched a dime of TV money. I put it in the bank and live off the money I make as a stand-up comedian.

If you had an agent, he would have told you, “Let’s try to get a counter-offer and start a bidding war.”

LENO: Yeah, it’s stupid. My thing is, if I always make a couple bucks less than whoever the highest-paid guy is, then you’re fine. You can’t eat the whole pie. If you eat all the pie, you’ll get fat, choke, and die. If you eat as much as you want and then give someone else some pie, then you have all these friends who are thrilled because you gave them a little piece of pie. It’s not that hard.

To what extent do you think your modesty and longevity are a result of the way you were raised?

LENO: My family was extremely stable. I had great parents. I wasn’t one of those drunk-father or whore-mother deals. I had a wonderful childhood, and I never had any problems.

If I had anything, it was a sense that my mother came to this country when she was eleven. My grandmother had run off with a younger man, and my grandfather had too many kids and couldn’t afford them. So my mother came to America to live with her sister, and always had a sadness that permeated her. Her natural inclination was not to be laughing. So when I was a child, I always felt I had to cheer my mom up somehow. To get even a laugh out of my mother was seen as a huge thing.

What do you think you’re going to miss most about The Tonight Show?

LENO: I don’t know. I’m a creature of habit and I like doing the same thing every day. I won’t really know until it’s gone.

Is there anything you’re wistful about? Like, “This is the last time I’ll be on this stage” or—

LENO: No. I mean, I enjoy it and I love the people and it’s fine. But what happens the day we leave? A truck comes through here and knocks all this down and it ceases to exist on any level anywhere. It’s gone. So you can’t grow that attached to it. The first thing about show business is, you don’t fall in love with a hooker.

Evidently, Leno fell in love with the hooker: Nine months later, when both Leno’s new program and The Tonight Show failed to deliver strong ratings, Conan O’Brien was given thirty-three million dollars to step down and allow Leno to return to the show.

* Branford Marsalis, who used to lead Leno’s on.air band, felt even stronger about some of the musical acts he had to tolerate: “I haven’t heard anything new that I’ve liked on the show. A lot of the bands we play with are just bad, especially those alternative rock bands. They can do it in the studio, but they can’t play live . . . I see the audience applauding while they’re playing, and I wonder if it’s just because they’re fans of the band and don’t care, or out of spite. Because it certainly isn’t because they sound good.”

[ THE GAME ]

SCENE 1

The Game didn’t want to take his shirt off.

Though the rapper had no problem posing with his muscles flexed and tattooed torso exposed for the cover of his number one debut album, The Documentary, he didn’t want to go shirtless for his Rolling Stone photo shoot. He refused to pose in a tank top as well.

After a few minutes of photos in a black beanie, faded blue jeans, and a baggy white T-shirt that bulged on the right side in the outline of a pistol grip—perhaps the quickest shoot in Rolling Stone history—Game jumped into his black Range Rover and pulled out of the West Hollywood studio, followed by the rest of his entourage in matching Range Rovers.

Why didn’t you want to pose without a shirt?

GAME: I got the number one album in the country, so I can do what I want. I don’t have to let myself get pushed around by anybody (nods head and smiles). I’m platinum, man. I’m already a millionaire, and I haven’t even gotten a rap check yet. That’s just off my mix tapes and my endorsements.

And soon you’re going to get royalty checks.

GAME: Fuck those checks. I don’t even need those checks, man. I’m not looking to make the bulk of my estate from rap. I’m looking at investments, endorsements, movies. Movies is really where I want to end up. The Ice Cube money has to be good.*

So do you see yourself as an artist or a businessman?

GAME: I’m a businessman. At the end of the day, I’m a young black entrepreneur, man. Rap is my tree stump. Then you got all these branches: You got the Nike deal, you got the Vitaminwater deal, you got the Boost Mobile deal, you got the movie shit. I mean, even my son’s everywhere: He’s about to do a Sean Jean deal and he’s got Huggies calling.

He slams on his car brakes and screeches around the corner of Melrose and Spaulding.

So where are we going now?

GAME: To the car wash. This is the best place in LA to get your car washed. And it’s only seven bucks.

[Continued . . .]

* Ice Cube on directing: “The money restraints are the only thing that made me feel like I was over my head because we did not have enough money to shoot a lot of scenes I wanted in the picture. If I had two million more dollars, the movie would be shot better.”

[ THE NEPTUNES ]

SCENE 3

Two days later . . .

PHARRELL: Hey, it’s Pharrell. Sorry it took me so long (phone crackles) . . . Yeah, go ahead, man.

So I’ll make this quick. I just wanted to—

Pharrell: Uh-huh (crackling). Hold on one second . . . Ben, dial 438-7897 and tell her I’m on my way over there . . . Okay, dude, can I call you right back? I promise I’ll call you right back. I want to do this story.

[Continued . . .]

[ LOVE ]

Led by one of the few African-American psychedelic rock singers of the sixties, Los Angeles band Love released one of the genre’s greatest albums, Forever Changes, a beautifully orchestrated masterpiece shot through with surreal lyrics. Plagued by drug abuse, arrests, and madness, the band just barely survived the era. The following is from a telephone interview with reclusive Love leader Arthur Lee.

What’s your favorite backstage story?

ARTHUR LEE: I was backstage, having to listen to Janis Joplin sing. The Grateful Dead was opening for us. I was wearing triangular glasses, and Pigpen* came back to the dressing room saying, “You know what they say about people with triangular glasses? They have triangular minds.” I sort of nodded, but then, when I was talking to the rest of the band, I realized what he meant. If I had realized it right away, I would have broken both of his legs.

What did he mean?

LEE: You know.

I don’t think I do.

LEE: (Silence.)

So what are your plans for your new record?

LEE: When I wake up in the morning, I want to see me rise on the horizon. That’s how big I want to be.

That’s pretty big.

LEE: Yeah, pop music needs a king and I’m it.

One of my favorite lyrics of yours is, “Oh, the snot has caked against my pants / It has turned into crystal.” A friend of mine heard it once and said, “Whatever drugs he’s on, I want to be on.”

LEE: What? There wasn’t any drugs involved.

He was saying it metaphorically, as a compliment.

LEE: No drugs! (Click.)

Hangs up.

Shortly after this interview, Lee was imprisoned for firearm possession. He was released five-and-a-half years later. In 2006, he died at age sixty-one due to complications from leukemia.

* Former Grateful Dead member who died of a gastrointestinal hemorrhage at age twenty-seven.

[ THE GAME ]

SCENE 2

The Game’s arrival at the car wash caused something of a commotion. Teenagers pulled his CD cover out of their cars to get autographs; a friend of Game’s showed off his new seventy-thousand-dollar Mercedes-Benz; and a music manager ushered Game into his SUV to hear unreleased tracks by a rapper named Smitty. As he got out of the SUV, Game boasted to the manager . . .

GAME: I met with [film producer] Joel Silver. He wants to sign me for like five movies. He wants to make me the next DMX (pauses), but without the crack.

Have you acted before?

GAME: I’m just multifaceted. I got a great personality, so I could do that. You can tell doing the interview that I can pretty much do whatever. If they tell me to act like I’m crying, I’ll act like I’m crying. It’s no big deal. I’m not shy at all. (Waves at a friend walking past.) That’s Steve, one of my white homies. I got white homies, too.

I’ve noticed that with everything you do, you have this drive to be successful no matter what it takes.

GAME: Pretty much. I give a hundred percent to anything that I do, whether it be selling crack or fucking in the booth with Dr. Dre.

How did you start selling crack?

GAME: I didn’t sell crack because I wanted to fuck anybody’s life up. My mom will tell you that she doesn’t regret the things I used to do for money, because I did what I had to do to feed my family. And as a man, we all should, no matter what it is.

But if you got busted, then you wouldn’t have been able to feed anyone.

GAME: Yeah, that’s one way of thinking about it. I mean, me selling crack on the corner in Compton didn’t contribute to the crack epidemic in America. Take me off the corner and put me in college playing basketball, and there would be another guy on that corner selling crack. I had to do what I had to do to survive. Anybody would do it. And the people that don’t are the people with no willpower, and we see them with signs when we’re getting off the freeway.

What was the first money you ever made?

GAME: The first money I ever made was probably not made. It was probably stolen.

From who?

GAME: From my grandmother, man, or my mom or something. I was a real ass-hole to my parents and my mother and my grandmother, and I’ve spent the last three years making up for it. My mom is happy now. She’s got a cameo in the new video.

Is there any parallel between the way you got to the top as a rapper and as a crack dealer?

GAME: I got successful dealing crack just by having the best supply, man. A lot of people, they don’t know how to cook crack. You gotta do it right. And even though the financial reward isn’t great in the beginning, it’s about having longevity, you know what I’m saying. Everybody’s going to come to where the good shit is. The good car wash is on Melrose: Everybody comes from far and near to the great car wash. The problems come when you’re trying to make money fast and not making good product.

Did other dealers try to take you out?

GAME: Yeah, that happened. I got shot. Well, I don’t know if that’s why they shot me. I didn’t get to ask them before they left. I really think that had a lot to do with it though, man. And it worked. They got me out of the building.* But, hey, I’m rich now, so who cares?

Is there anything you could have done differently that night to prevent it from happening?

GAME: Yeah, I could have not opened the door at all, which was my first instinct because when dealing drugs, you have to have an order of operations and you have to have rules. One of the rules was not to deal drugs after twelve a.m., and it was almost two in the morning. I was greedy, man. I opened the door, and in came the infiltrators. They were like the Decepticons.† It was like me against them and I was outnumbered. But I lived through it, man. I can honestly say that I wouldn’t wish that on anybody, man. Bullets aren’t the best feeling in your stomach.

Do you ever worry about getting shot like Billboard?‡

GAME: I’m not a pussy, man. I know that death is coming. It’s not something I’m scared of or running from. It’s gonna happen. So it’s me against time right now. I’m fighting time to get all this shit done before my time is up.

How do you feel then about the times you’ve been on the other end of the gun?

GAME: I did drive-bys with my brother Fase. And we did gangbanging for a long time. But I also went to school and made straight As and got a scholarship to a legit top ten college. I don’t have any regrets to this date about things that I have done, good or bad, because I never did anything to anybody who didn’t impose threat or harm on my life or my family members. I kind of felt like the people I did things to deserved it, because I’ve never started any wars.

But you’ve finished them?

GAME: I’ve finished quite a few of them, man.

I noticed that you were strapped.

GAME: I’ll be strapped for the rest of my life. It’s just my comfort level. I’d rather spend money on lawyers and fight a case than be dead in a coffin fighting nothing.

[Continued . . .]

* In 2001, three men entered the apartment complex where Game sold drugs in Bellflower (near Compton), shot him five times, and left with his money and drugs. After he woke up from a three-day coma, Game decided to find a safer way to make money, so he started learning about rap—and real estate.

† The villainous alien robots in The Transformers.

‡ Game’s best friend, sidekick, and rapper, who was shot by a rival gang member.

[ MUSIC LAWYERS ]

One of the more unpleasant duties of being a journalist is dealing with attorneys. To call them liars would be libelous, so it may be best to let one’s words speak for themselves.

You were going to give me an accurate account of—

LAWYER: I was going to run through this with you.

Right.

LAWYER: The first accounts, particularly the ones on TV, had the following statements in it: One, she had overdosed on heroin and, two, she was rushed to the hospital and was under the influence of heroin. Both of those are absolutely false. First of all, she did not overdose on anything and was not treated in the hospital for an overdose.

So why was she in the hospital?

LAWYER: She had an allergic reaction.

To?

LAWYER: To, uh, er . . . I’ll think of it in a minute, but . . . I’ll think of it before we get through. But she had an allergic reaction . . .

So where did the overdose information come from?

LAWYER: I don’t know. I can’t, uh . . . I can’t be responsible for inaccurate press reporting, you know, as to where or how . . .

I was just wondering if you had any idea who would have—

LAWYER: Yeah, irresponsible people in the media! Um, hold on one second. I’ll get you the name of that thing or I’ll keep thinking about it (sounds of movement and rustling papers). Xanax. It’s some kind of prescription drug. I shouldn’t even say drug. It’s a prescription medication that you take to deal with depression.

I don’t think it’s an antidepressant.

LAWYER: Well, that’s a little harsh. That kind of sounds like Prozac or something. It’s a medication a doctor gives to you. It’s a mild version of Valium. Something like that. But it’s hardly . . . It’s not something that’s abused.* It’s not something that is some kind of drug, which you get high off of.

I guess it wasn’t something she had been taking previously if she had an allergic reaction to it.

LAWYER: Whether she was or wasn’t, I don’t know, but, uh . . . In other words, I don’t think this or anything else opens up her entire past medical history. She had an allergic reaction to it.

And what about the heroin?

LAWYER: She wasn’t under the influence of heroin. She didn’t overdose. I spent two hours with her at the police station and was with her for two hours afterward. I have been practicing criminal law for twenty-five years and have seen people under the influence of all kinds of substances, and she was absolutely sober. In fact, she was not booked for being under the influence.

What was she booked for?

LAWYER: She was booked for four things. One, felony possession of narcotics.

Two, felony possession for receiving stolen property.

What was the stolen property?

LAWYER: The charge was about a prescription pad that was found in her hotel suite. The simple answer is that we’ve interviewed her doctor and the doctor left it there when he was visiting her. So it’s not stolen property. There were no prescriptions written on it. It’s the business of the police to investigate it, but I’m confident that’s going no place.

And what were the other two charges?

LAWYER: Another charge was possession of drug paraphernalia. The fourth one involves possession of a hypodermic needle, which is a separate charge.

But none of those have any bearing on her admittance to the hospital?

LAWYER: No! Oh, she . . . no . . . None of them at all.

Right. So with the narcotics charge you mentioned, what was that?

LAWYER: It was not narcotics! It’s some . . . it’s . . . the police find white powder—or something that looks like white powder. So they arrest somebody for possession of drugs. But it’s not drugs! I know what it is. I know where it came from.

Would you be able to tell me?

LAWYER: Sure! Absolutely. It’s a Hindu . . . It’s Hindu good luck ashes, which she received from her entertainment lawyer.

So that’s not something one administers orally or shoots up?

LAWYER: Well, I don’t know what you do with Hindu good luck ashes. I think you . . .

I don’t know, either, so I was just asking.

LAWYER: Okay, I suppose you carry them around with you for good luck.

So it’s not something you would ever ingest?

LAWYER: No, you don’t ingest it! No. It’s certainly nothing that you drink or eat. I mean it’s . . . I certainly haven’t decided to study the Hindu faith in order to properly represent her. I know it’s not drugs. I know where it came from.†

So I guess what you’re saying is the only charge that holds any weight is the hypodermic needle?

LAWYER: They did find a hypodermic needle. And we were able to explain what that was doing there and it was not there because of the administration of drugs.

Why else would it be there?

LAWYER: Well that’s . . . I’ll tell you what: Go to court and you’ll find out.

* According to H. Westley Clark of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Xanax can be and is abused. The effects should not be minimized.” In 2008, thirteen million people were estimated to be abusing drugs in the Xanax family.

† A Google search at the time of this book’s publication produced no independent results for “Hindu good luck ashes.”

[ KORN ]

SCENE 2

When a rock band is at its peak onstage, there are few spectacles more powerful and awe-inspiring. That’s one of the reasons why women throw themselves at bands afterward. But what fans and groupies don’t see is the mess that many bands are before going onstage. The day after Davis’s rant about getting no respect, Korn was in a courtesy van on the way to the Fuji Rock Festival in Tokyo for its first live show in thirteen months.

FIELDY: I need a drink.

JONATHAN DAVIS: I’ve never seen you drink this early. You’re fucking nervous.

FIELDY: I threw up this morning. Everyone else is so nervous, every time they think of the show they get ill. I took a whole bar of Xanax.

MUNKY: My heart’s beating a hundred miles an hour. And I can’t feel my hands. I’m not kidding.

DAVIS: I’ve done seven thousand shows before, and I’m still fucking scared. I woke up at five this morning and wrote out the lyrics to every song and sung them from top to bottom. I feel sick.

HEAD: Be strong, man, like Ozzy. He’d just get up in the morning, drink forty bottles of Jack, and be onstage.*

DAVIS: I’m not a man. I’m a bitch.

HEAD: Yeah, actually I’ve got anxiety for the first time. I had a dream that Caco [the guitar tech] fucked up my pedal board and there were only three on there. Then I had a dream that you guys switched the songs around on me and didn’t tell me. I kept playing the wrong songs.

FIELDY (tauntingly): Head’s gonna fuck up in front of fifty thousand people onstage. You could have major shit go wrong with your pedals. If one went out, you’d be fucked.

HEAD: No, I wouldn’t . . . Then I had a dream that Rosie O’Donnell was our accountant. She called me and said, “I hate this fucking TV show crap. What I really want to do is get you your money.”

MUNKY: Whose dick hurts from jacking off?

Backstage, the band’s nerves haven’t calmed any.

FIELDY: Let’s all walk to the stage together, like a gang, know what I’m saying, brother. The whole posse. Everybody. (The band begins to walk toward the stage.) Walk slow. It will make you more confident.

DAVIS: I can’t walk slow. I’m too scared.

HEAD (to Loc): If I suck, will you tell me I was great anyway?

LOC [Korn’s bodyguard and minder]: No, I’ll tell you that you sucked and need to get in shape.

The show, as predicted, is a disaster. Head cracks himself in the head with his guitar, and the black stage is so sun-baked that the entire band seems to be on the verge of passing out. Nonetheless, tens of thousands of Japanese kids, never having seen Korn before, go wild, even opening up a mosh pit (a rarity at Japanese shows). As the band exits the stage . . .

FIELDY: We sucked. And you can print that.

DAVID SILVERIA: Are you going to write about how shitty we were?

Really, you weren’t so bad, but the end got loose.

SILVERIA: I didn’t get loose. I made it all the way through. The rest of the band fell apart.

Half an hour later, Davis approaches me.

DAVIS: What the fuck should I do?

About what?

DAVIS: I’m fucking through.

No you’re not.

DAVIS: Yes I am.

No, you’re psyched. You did your show and you got the props you wanted.

DAVIS: Yeah, I did good. What’d you say about the band? Loose?

Everyone has good days and bad days.

DAVIS: We’re Korn. We’re not ever loose. How the fuck do you think you got here?

You gotta have your off gigs?

DAVIS: Never. Never ever ever.

So are you pissed at the band?

DAVIS: It’s not their fault. It’s our first time in Japan. It’s been a year since we last played. Fieldy’s drunk off his ass and delirious. And Head thinks he’s knocked himself half-conscious and goes to the hospital for stitches, and they give him a Band-Aid. Do you see what I’m stuck with here? It’s four against one.

The following day, Davis breaks down. Literally. He has an anxiety attack, and spends the rest of the trip in bed with Loc babysitting. When I come up to visit, Munky is standing loyally outside his hotel room.

MUNKY: I feel so bad for Jonathan. I just massaged his back. But sometimes I just don’t know what to do for him.

Inside the room . . .

How are you feeling?

DAVIS: A bit better.

Has this happened before?

DAVIS: My first anxiety attack was like five years ago: too many damn Mini Thins.† Drinking and that gave me anxiety. So they had to get Loc for me. With alcohol, I get too drunk and wake up, and it’s like withdrawal. I get the shakes, I’m sweaty, I’m freaking the fuck out. And the stress: full-on stress. My stomach’s just spitting out acid in my throat (smiles feebly). But I guess everything’s got to be dramatic or it wouldn’t be fucking good.

Or you could just stop drinking?

DAVIS: My psychiatrist says he should be helping me, but he’s just looking for ways to get me high. But maybe I should start taking antidepressants—or go to AA. When the band’s all joking around, the only way I feel comfortable with them—like I can join in—is when I’m drunk.

Let me know if there’s anything you need tonight.

DAVIS: It’s okay. I’m sorry I can’t kick it in Tokyo with you tonight, dog. I’ll make it up to you. I’ll take you to Bakersfield.

LOC (privately, to me): I’m doctor, psychiatrist, brother, bodyguard, and father to these guys. Everyone’s scared of them, but, really, they’re just kids.

[Continued . . .]

* Ozzy Osbourne actually suffers from severe stage fright.

† A diet pill containing ephedrine that truckers and others use to stay awake.

[ THE NEPTUNES ]

SCENE 4

Four hours later . . .

PHARRELL: Hey, I want to do this fucking interview. The fact that you guys chose us and the fact that you’re even interested . . . I want to give you whatever you need. Ask whatever you want.

Okay. You were starting to tell me before about the projects you were working on right now.

PHARRELL: Right now? . . . Hold on . . . (To someone else: ) See if we can get more money. . . . Can I call you right back?

[Continued . . .]

[ BACKSTREET BOYS ]

SCENE 3

Kevin Richardson returns from the bathroom and we head to his car, where he plays new recordings the Backstreet Boys have been working on.

With your Greatest Hits record, I felt like maybe your record company or managers needed money, so they rushed it out.

KEVIN RICHARDSON: Let me tell you what, the five of us wanted to put our greatest hits album out on our ten-year anniversary. That’s what we wanted to do. We thought putting it out now was too early in our career. That’s why we called it Chapter One.*

Shouldn’t your management company be fighting on your behalf?

RICHARDSON: Well our management company was supportive of the album and we weren’t. And the record company was going to put it out anyway. So it’s either promote or fight with your label, don’t promote it, and risk it doing very badly. But ultimately, who is it that’s going to get hurt? It’s not going to hurt our label. It’s going to hurt us. But it’s just frustrating because the five of us are trying to do things for a long career and it’s like our label sometimes, man, whatever. It’s a necessary evil. I don’t want to be bitching, but . . .

But they’re just going to work you until you die if you let them. Don’t you feel like taking time off and just not being a Backstreet Boy?

RICHARDSON: That’s true, and it was also our decision at first. We didn’t stop for five or six years. But when Brian [Littrell, his cousin and bandmate] went in to have open heart surgery, it made me realize, like, “Wow, what are we doing? We need to maybe slow down and take care of ourselves.” Because even I was like, “Let’s go, let’s go baby, let’s do this.”

Did Brian’s illness have anything to do with how hard he was working?

RICHARDSON: Yeah. Brian was born with a congenital heart defect. He had a hole in his heart and he had to go every year to get checked up. And this one year, we had toured so much and he had been, you know, going, going, going, so this hole was getting bigger. The doctor said, “You need to get that taken care of.” And I remember management at the time saying, “Well, can’t you postpone it so we can finish this tour?” And this just hurt Brian so much, ’cause he’s like, “Dude, this is my heart.”†

Wow, that’s cold.

RICHARDSON: Yeah, that opened all of our eyes. Though even at that point, to be honest, I was still cracking the whip—“aw, man, come on, you got to go”—until I saw him in the Mayo Clinic after his surgery. It really woke me up and I was like, “You know what, this is my cousin. He just had his chest split open and his heart out. And here I am worrying about getting back out on the road and selling records.” It was a big wake-up call for me.

How did Brian feel about you cracking the whip at that point?

RICHARDSON: Brian felt hurt, you know. I hurt him. He felt like we all hurt him, because we didn’t understand. But after that, I understood him even better. That brought us all closer.

What would you do if it all ended tomorrow?

RICHARDSON: Wow, wow. I mean, if it all ended tomorrow, meaning if nobody gave a damn about us and we didn’t sell another record?

Yes, exactly.

RICHARDSON: I just got married and I want to start a family in a couple of years or whatever. If you can’t enjoy your friends and family and your success, then what good is it? Because, you know, it’s nice having fame and having some money in your pocket, but—it sounds so cliché—that ain’t what it’s all about. I didn’t have no money before, and those were some of the happiest times in my life. You don’t want to be wealthy and just worn out—grumpy and old and depressed because you have nobody to share it with.

After the Backstreet Boys released their next album, Never Gone, Richardson left the band. A year later, he and his wife, Kristin, had their first son, Mason.

* Almost a decade later, there has yet to be a Chapter Two released.

† Asked to respond to the accusation, Pearlman said he supported the band taking time off for Littrell’s operation immediately.

[ KORN ]

SCENE 3

A week later, Jonathan Davis came through on his promise. He and his minder Loc picked me up at my house and drove to Bakersfield, where “there’s nothing to do but drugs and drink and fuck,” as Davis’s nineteen-year-old half-brother Mark explained when we arrived.

“We could go stop off and pick up a couple of hoochies if you want,” Mark offered soon afterward. “And they’re not bad looking, either—asses tighter than a motherfucker.”

Davis passed on the hoochies. “I’ve been with the same bitch for seven years,” he said. “My mack went bye-bye.”*

After a tour of the town, including the high school where he was bullied and the mortuary where he used to work, Davis picked up his father, Rick, and drove to his dad’s recording studio. The two were the spitting image of each other.

RICK DAVIS: When I was Jonathan’s age, I had hair all down my back and was traveling around the country playing music. Who’d think I’d become old and fat, working at a government-funded TV station?

Did the [Korn] song “Dead Bodies Everywhere,” about how you didn’t want Jonathan to be a musician, ring true for you?

RICK: Initially there was a nervousness on my part. But [the song] forced us to sit down and go over all the issues and resolve them. And we did, didn’t we?

JONATHAN DAVIS (obediently): Yeah.

RICK: I had lost everything in bankruptcy and I was going through a divorce, and at that moment I looked at my son and said, “Always have a day job to fall back on.” And fortunately he didn’t listen to me. But everything’s okay now. We never had bad blood?

JONATHAN: No, we were both fucked up.

RICK: I still remember when I drove back home after you moved to Long Beach. When I saw you were living in one corner of a garage, you have no idea how many buckets I cried driving home. But I thought, at least he’s pursuing his dream. How would you feel if you saw [your son] Nathan living like that?

JONATHAN: Yeah, you’re right. I wouldn’t like it.

RICK: Now you know why I did what I did.

JONATHAN: I never realized how hard it is being a parent. We bought Maine lobsters once. I didn’t want to kill them, so in the end, [my wife] Renee did. I was a little drunk, I think. And I told Nathan as a joke, “Your mommy just killed Sebastian [from The Little Mermaid].” I feel so bad about it now.

RICK: I’ll be damned. Now you’re a little drunk in front of your kid, making music and touring all the time, just like I was.

When his father leaves to go to the bathroom, Jonathan shakes his head in disbelief . . .

JONATHAN: Since I was thirteen, all we talked about was pussy. It wasn’t until I started writing songs about him that we started talking about all that other stuff. He’s not that bad now. But at that time, it felt horrible. When he asks me, “I wasn’t a bad dad, was I?” what am I going to say, “You were an asshole”?

It does seem like he’s trying to justify his behavior, but at least you can empathize with him a little more now.

JONATHAN: Ever since I’ve had a kid, I totally have new respect for my dad. He did fuck me over, but I can understand why. When he left to go on the road, he needed to put food on the table. He needed to pay hospital bills. I was asthmatic. I was in the hospital every fucking month from the age of three to the age of ten. When you’re three years old, you don’t think about that shit.

So do you think Nathan is going to grow up with hard feelings because you’re gone all the time like your dad was?

JONATHAN: Probably definitely. It really freaked me out when I left to go to Japan and my son said, “You got to go to work? Bye daddy!” Then he rolled over like, “Don’t talk to me.” It hurt my feelings more than anything in the world. I don’t give a flying fuck about this whole band. I just want to make my son happy.

That’s one way of looking at it.

JONATHAN: It’s a way that can keep me sane.

When Jonathan’s father returns, the two spend some more time trying to connect, then we drive him home. As he leaves the car, Jonathan’s dad smiles wanly and says . . .

RICK: I’d tell you that I’m proud of you, but you already wrote a song about it, so I don’t know what to say.

Jonathan waves goodbye to his father from inside the car. As we drive away . . .

JONATHAN: So what’d you think of Bakersfield?

It’s a shitty place to live and a shitty place to visit.

JONATHAN (triumphantly): You’re pissed off. And you want to start a band called Korn, right? Now you understand—and you’ve only been here a few hours.

* Three years later, Davis and the “bitch”—his high-school sweetheart—divorced, and he married a porn star.

[ TRICKY ]

During our first interview, Tricky discussed his work with the dance-music collective Massive Attack and his skittish solo debut, both of which have come to define the genre known as trip-hop. For our second interview, he brought a photo album to a bar in Los Angeles and sat for an hour and a half telling tales about each person on the maternal side of his family, going back five generations. What follows are just a few stories from his family tree. All effort has been made to make sure that, in the jumble of information he manically regurgitated, the names and relationships have been reported accurately.

Great-great-grandparents

They were horse dealers and they had orchards. They brought horses from Ireland, and someone got hung.

Great-grandparents Arthur and Maggie

Arthur was a champion fistfighter of Knowle West [in Bristol, England]. He fought the king of the gypsies and won. All his children were boxers.

Great-uncle Martin

My auntie says he was born evil. I remember saying to her, “Why is everybody always so scared of Martin?” And she goes, “Because when he says he’ll cut your throat, he’ll cut your throat.”

Martin used to get drunk and go smash everybody’s house up. He stabbed someone fourteen times. Fourteen times! He went to Manchester and opened an illegal club, and what he used to do with opposition clubs is he’d walk in right past the security with a can of petrol, pour it on the floor, and fucking burn it down.

Great-aunts Maureen and Olive