![]()

Family, Youth, Education

![]()

EVEN THE BASICS are complicated. My father, originally named Ilija (Ilya) Gershon Rochelson, was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, on August 19, 1907. But Kaunas was known as Kovno (or Kovne) to the Jews for whom it was home, in some cases for centuries, and in 1907 it was not part of a country named Lithuania but rather a city in the Russian empire. The Jews who lived there, however, and in neighboring areas (many, like my mother’s ancestors, in what is now Belarus) considered themselves to be Litvaks.1 Moreover, August 19 was September 1 in much of the world, but my father’s birth date was recorded under the Julian calendar, used in imperial Russia until the 1917 revolution. When in August Dad told us not to celebrate his birthday because he really was born on September 1, I never quite believed him, although perhaps I should have.2 I thought it was just survivor guilt preventing him from fully enjoying the pleasures of his new life, the congratulations we all felt he deserved, even though I knew about the thirteen-day calendar difference. The August 19 date persisted in most of my father’s official records, and it is the date that we, his American family, had carved on his gravestone after his death in 1984. Then, when I traveled to Lithuania in 2003 and obtained copies of vital records filed in the Jewish community archives, the Hebrew dates and an online Jewish/civil calendar3 confirmed it: my father was born on the twenty-second of Elul, which coincided with September 1 that year. His brit milah (ritual circumcision) was performed exactly when it should have been, on the eighth day following his birth, the twenty-ninth of Elul.4 I could only imagine the excitement in the house, and the nonstop preparations of his mother and other relatives as they prepared a family celebration for the day before Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year.

Jews are said to have lived in Lithuania since as early as the ninth or tenth century, CE, with extensive settlement beginning in the 1300s when King Gediminas invited foreigners to help build his empire (Greenbaum 1–5). Eli’s family had been in Lithuania for generations. His grandparents, Eliyahu Gershon (for whom he was named) and Devorah (Dvera) (figure 5), were born between 1830 and 1833; his great-grandfather was named Moshe (Movsha on some records), and a number of records spell Movsha’s son’s name as Eliash.5 During the childhood of my own grandfather—known in the family as Bere-Mikhel, but often Mikhel-Ber Rochelson in official records—the family lived in Veliuona (known by Jews as Velion), a town about midway between the two larger cities of Jurbarkas (Jurborg) and Kaunas (Kovno). Eli’Gershon and Dvera’s surname was Rochelson, but family genealogists have discovered that earlier generations used the name Michelson and, before that, Kielson. The standard explanation is that the name was changed when it seemed expedient to avoid compulsory service in the tsar’s army, service that was particularly harsh for Jews.

Figure 5. Formal portrait of Devorah (Dvera) and Eli’Gershon Rochelson, Eli G. Rochelson’s paternal grandparents. Family collection.

At the time of Bere-Mikhel’s birth, in 1864, his father was listed as owning a “drinking house” (LVIA728/1/873); indeed, being a tavern keeper was a frequent occupation for Lithuanian Jews, and Eli recalled his parents running a similar concern. A later record, of May 30, 1893, indicates that Eliash Gershon (Eli’Gershon) was a timber merchant who left Veliuona for Kaunas.6 However, I became aware of his occupation decades before the internet made these records available, when an announcement of my marriage in the New York Times in August 1975 came to the attention of Manfred Rochelson, who lived in Queens, New York. He contacted my parents in Brooklyn, and they met for the first time. My mother told me that Manfred’s resemblance to Eli was uncanny. He spoke of the German branch of the family, based in Berlin, and mentioned a family story that each Hanukkah they received a smoked goose from relatives in Lithuania. My father had no recollection of such gifts, but a phone call to cousins in Tulsa (the descendants of Dina Sanditen, one of my grandfather Bere-Mikhel’s seven sisters) confirmed that Lithuanian Rochelsons had sent a smoked goose, as described, every year. Manfred also confirmed that the German Rochelsons were in the lumber business, receiving timber from the rich forests of Lithuania via the Jurborg-Velion-Kovno branch of the family. Bere-Mikhel was born on July 17, 1864 (old style); internal passport data shows that his wife, my grandmother Henye Lubovsky Rochelson, was born in Naumiestis in 1869.7 Naumiestis (New Town) was a place called Naishtot (Neustadt) by the Jews, and there were in fact several Lithuanian towns by that name. Henye’s—Kudirkos-Naumiestis—was close to East Prussia, home of Königsberg, which became Kaliningrad in Soviet times and is now again an enclave of Russia.8 Kudirkos-Naumiestis is in the district of Šakiai, where my grandmother was living at the time of the Nazi invasion, and where she died at the hands of Lithuanian partisans.

Bere-Mikhel was the only son among eight siblings who lived to adulthood, and he died prior to the Holocaust, in 1932. His sister Dina Glike,9 emigrated to the United States and became the matriarch of the large Sanditen and Fenster family in Oklahoma; one of her descendants, named Deana after her, confirmed Manfred Rochelson’s story of the Hanukkah goose. Dina’s eldest daughter, Rivka (also spelled and pronounced Rivke or Rifke) lived for some time as a teenager with Bere-Mikhel and Henye’s family, going to school in Kovno. There she became close to their daughter, Chaya (Chaye, later Anna). If Eli was alive at that time, he would have been a baby, but in the United States he had fond memories of his cousin Rifke, whom he certainly knew in later years; she, her husband, and her two eldest children left for Tulsa as late as 1922 (figure 6). All of us met Rifke in 1960, a year before her death, when we visited the Tulsa family for Thanksgiving. Greta Minsky, one of Rifke’s granddaughters, suggests a reason for the bond between Eli and Rifke: “they both loved Chaye.”10

Figure 6. Chaye with the Fenster family, shortly before their emigration to the United States. Chaye is dressed in white, on the left; Rivka (Rifke) is standing; her husband, Gershon Fenster, is reclining on the left, and the two very young children are their son, Louis, and daughter, Rosalee (later Minsky); their youngest child, Irving, was born in the United States. I cannot identify the other two people. The message on the back reads, “For my beloved and dearest ones, brother [David] and sister-in-law [Ida], from your sister, Chaye” (translation from Yiddish by Rivka Schiller). Family collection.

Eli was also close to the children of his mother’s brother Mordkhel (Mordechai), some of whom I came to know as well, since his daughters Genya and Riva survived the war in the South of France and later lived in Paris. Eli’s maternal grandfather was David Lubovsky; I do not know his maternal grandmother’s first name, although my father mentions her, too, affectionately, in his account. Only recently did I discover the existence of a sister of my grandmother, someone of whom I had never been aware although she immigrated to the United States in the late nineteenth century, losing her life in a Brooklyn trolley accident in 1909. I have met several of her descendants, and together we’ve confirmed the connection. That story comes later, as do the stories of other cousins.

When Eli was a child his family lived on Yatkever Gass, the Yiddish name for the “street of butchers,” where many Jews lived in the Old Town (Senamiestis) of Kovno. It is now called M. Daukšos Street, and I easily walked the length of it when I visited the city, from its origin in a walkable branch of the major artery Jonavos Street to its termination at the Nemunas River, which Jews called the Niemen (see the map of Kovno and its environs in appendix A). I had no idea where on the street my grandparents’ home had been, but I assumed I had walked past it. My uncle David Robinson, Dad’s eldest brother, who was born in 1895 and lived in Miami Beach during the last years of his long life, told my son that one of his earliest memories was of seeing a circus parade with an elephant in the town square in Kovno, when he was a small child living in Yatkever Gass.11 In the interview with his son Burt, Eli talked about his early life there, too, recounting memories of home and family (see figures 7 and 8):

I had one sister and five brothers. My sister’s name was Chaye, and then the brothers were David (who changed his name for Robinson), then Maishe, Mottel, Avraham, and I.12 Then I have another sister, she died of a childhood infectious disease; as far as I can remember, I was told that she had diphtheria. My [surviving] sister Chaye had scarlet fever, and she developed rheumatic fever with a severe rheumatic heart disease.13 My father, at that time, when I was born, was working, at one time, in a brewery, by letting out the beer and counting, and by, when they came back from selling the beer, counting how many empty bottles they had, and how many they sold. After a while, he opened, we called it in Jewish an akhsanye.14 This I don’t remember, but I was told, it’s like a little motel, a hotel; I would say I would call it a rooming house. Of course it didn’t have the character, at that time, like it has here the motels. Now, then we moved, in a small street in Kovno called Yatkever Gass, where my parents opened a restaurant. I started to remember events, I think, when I was five years old. My brother David, at that time, it was in 1912, he was carrying me, I remember, on his shoulders, and going around all over, the rooms and in the streets. . . .

We had, as I said, opened a little restaurant, where we had different type of high-cholesterol food, but very tasty. Every breakfast we had, let’s say, the fricassee from chicken, or from geese, boiled in soup with cereal, and then we had piroshkes made from dough with meat. That was our breakfast. There in this birele, or we call it restaurant, where we sold liquor, which we didn’t have a license to sell, and David had to—the police were coming in often to check if alcohol is sold. And many times my brother when he saw the police he threw away the bottle . . ., and they couldn’t do anything because they didn’t catch him with alcohol. . . .

Among Eli’s earliest memories were happy times with his extended family, especially his aunts and cousins:

We had there Tante Sarah with her children; her children were Feyge, Leiye, and Taibke.15 And then Minne had children, it was Uri, Grunye, and Paike. There was another boy, Yankele, who died, who drowned while swimming in the Niemen. Sarah is my father’s sister, and Minne is my father’s sister.16 Almost every Saturday, holiday, either we visited them in their house or we were going out, on the Naburus[?], that means near the river, where we were running around, taking wildflowers, and having a good time, I would say. For some reason or another I remember the flowers which have a very round type of appearance, and when they blew, it flew away. . . . And after a couple of weeks there were a tiny button-like green fruit which was not edible. But we had a song, “run around the beigelach,” we called [it]. Then also there were yellow flowers, and different wild flowers.

Figure 7. Formal portrait of the Rochelson family, ca. 1913. Left to right. Mottel, Ilija (Eli), Henye, Chaye (Anna), Bere-Mikhel, Maishe (Mishe), Avraham. The photograph on the table next to Chaye is of David, who was already in the United States. Family collection.

Figure 8. Formal portrait of (left to right) Avraham, Mottel, Maishe, Ilija (Eli). Family collection.

The park at the confluence of the rivers, close to Kaunas Castle, still hosts outings for city families on Saturday afternoons, and is called Santakos (Confluence) Park (figures 9a and 9b). It may also have been the place where Eli, his lifelong friend Joseph Kushner, and two other young men were photographed after a swim in the river in 1929 (figure 10). Lithuania is filled with natural beauty, and Eli’s love for nature, the countryside, and even the ocean, which he called “the sea,” began in that childhood life before the First World War.

Eli was just under seven years old when World War I began. As he described it, “In August 1914, we children were playing near the Niemen River, and we heard news that a war started.” He spent his childhood in Kovno until he was nearly eight, when Russian authorities, fearing that Jews who lived near the German border might be a fifth column as the German army advanced, expelled Jews from Kovno and elsewhere in Lithuania in early May 1915.17 Eli’s maternal grandmother traveled with them from Kovno. He described her fondly as “very sweet,” a woman who hid kopecks (pennies) and candies for the children to find, and to give to them as rewards. He remembered that during this time of travel or exiled settlement, “she got very sick, and she died from pneumonia, and this is very—This I remember clearly.” The family resettled in Russia, staying in Rostov-na-Donu (Rostov-on-Don), a large and historic port city in southern Russia, until 1921. Eli’s account describes the journey and his family life there and in other towns along the way:

Figure 9a. Where the Neris and the Nemunas meet. Photograph by author on visit to Kaunas, 2003.

Figure 9b. Wildflowers in the park at the confluence of the rivers. Photograph by author on visit to Kaunas, 2003.

Figure 10. Friends at the river, 1929; Joseph Kushner is at right, Eli Rochelson is next to him; the other young men are unidentified. Gift of Joseph Kushner to the author.

Within 24 hours we had to leave Kovno. . . . [W]e put everything together, our pillows, and blankets, and pots, whatever we could, we loaded on a horse and carriage, and we went to our relative. That is another sister of my father, Yente; there were two daughters she had. We went to [a place] called Žežmary.18 I wouldn’t know how many miles it was, but I do remember that the horse got stuck in the deep sand, like dunes, and it was unable to go. We pushed the carriage, we pushed the horse; finally we came there and we stayed there for a short time, and we returned back to our house, to our house in Kovno. But seems to be there was another order from the tsar19 that not only from Kovno but [ . . . Jews from many areas] have to leave Lithuania. Because they suspected that the Jewish people, by knowing Jewish language, which is similar, the derivate from German, may become spies for Germany.

Then we again went through the same ordeal. We went to, all the Jews went to the railroad station, we went to a train, and we were traveling a day or two. As a child, at that time I was six years old, I would say already seven. When we came, I remember vividly, when the train stopped, and they said, “You can go out now.” It was a small town, and the light was visible, the light over the leaves of the trees, and to me it was a fascinating picture. At night, the electrical light and the trees. We slept overnight at the railroad station. And then, the next morning, the Jewish organizations which were there, in Khorol, a little town near Kharkov . . . ; they helped us out. We stayed for a while in Khorol but we didn’t like it. And then we moved to another small town called Izyum. Izyum is a little provincial small town belonging to the county of Kharkov.20 This town Izyum—the word “Izyum” means a raisin, but that was the name. Now in Khorol, also I remember, we rented a little apartment which was near a river. In the spring it was flooding, and we had to make, erect like little bridges with plain boards over wooden horses to walk out to the streets, because there was water, and in the house was water.

In Khorol and Izyum, where they stayed a bit longer, Eli continued the Jewish education he had begun in Kovno at age five or six, and enrolled in a tsarist Russian-language school. His sister Chaye, a young teenager when Eli was born, encouraged him to study Russian: “She was the one who guided us all through the years,” he remembered, “and even taught me and my brothers Russian, how to write and how to read.” Chaye continued to encourage Eli, nurturing his ambitions as he matured, and remaining an important influence in his life.

At school in Izyum, Eli experienced antisemitism for the first time. He recalled the school as having 90 to 95 percent non-Jewish students, who recognized the few Jews by their appearance:

Of course we looked differently, maybe we didn’t have a payah and yarmulke, but I wore tzitzis, and I was making tefillin every day and praying three times a day.21 But when we came there, there was the icons on the walls, with a big cross, and a pope was coming, and they also had, so-called coaching into the Russian religious topics. And they had, let’s say, with special writing in Russian Slavyonic [Slavonic] type of script.22 I had to learn that, and when we tried to say we are Jewish, they said, “never mind, you have to stand up, you have to pray.” The only thing, we didn’t have to cross ourselves. That they didn’t compel us. But what I remember, going home each time, I had to go different streets because we Jews—I personally remember on me they were throwing stones, attacking you, beating you up, . . . Usually we were attacked by kids the same age, maybe a little older, one or two years.

With help from local Jewish organizations as well as from vendors, Bere-Mikhel had opened a grocery store in Izyum. But the family didn’t like the life there, and when they heard from friends in Rostov-on-Don, they decided to go, hoping the larger city would offer better economic and educational opportunities. Oleg Budnitskii reports that Jews made up 7.2 percent of the residents of Rostov-on-Don in 1914, a population that grew to 9 percent (or 18,000 out of 200,000) by 1918, playing “a significant role in the economy and public life of Rostov” (16). The family lived in a suburb called Nakhichevan, known for its sizable Armenian population. That the Nakhichevan Jewish community was considered integral to Rostov is evinced in the name of one of its mutual aid organizations, the Association of Jewish Refugees in the Cities of Rostov and Nakhichevan-on-Don (Budnitskii 22). Eli recollected with pleasure how, in this town of southern Russia,

[w]e established in Nakhichevan a little . . . ice cream parlor, with a candy store and fruit. I remember we children, at night, we had our fruit, and watermelons, and grapes, and all type of tropical food, outside the store and inside, people were coming from all over the city because we did a very good job. We had different type of ice creams, and early in the morning we had by hand, we had to turn metal drums, with the sweet cream and sugar, vanilla or chocolate, and there we had also different kinds of pastries, and we made a very nice living. It wasn’t near our apartment house, but it was, oh let’s say, about, fifteen minutes or a half-hour walk to our house.23

The Russian school that Eli attended in Rostov was run by Iliya Shershevskii, a Jewish community leader who in 1918 helped found a Jewish Culture and Education Society. According to Budnitskii, the Shershevskovo Gymnasium24 was one of his greatest achievements, “a mixed (boys’ and girls’) private Jewish gymnasium, the first of its kind in Rostov” (Budnitskii 22). Eli studied Hebrew there, as well as Russian. He also continued religious studies at the local synagogue, where he attended services every Sabbath and on the holidays and sang in the choir. Since he was there until 1921, he would have celebrated his bar mitzvah in that synagogue. I remember him telling me once that the reception consisted of women throwing raisins and candies at him from the balcony, where they sat. If I had the opportunity today I would ask him many more questions—about the bar mitzvah and so much else. In his interview Eli recalled that, as a newcomer, he was harassed by some of the other boys when they played in the shul (synagogue) backyard. Finally, when he had had enough of one particular boy, a redheaded, freckle-faced child who was older and stronger than he, young Eli said to the others, “‘Look, boys, I will show you that this guy will never go to me near.’ And I gave him such a beating that since then I became one of the heroes and became friendly with this guy.” Telling the story to Burt, years later, he concluded, “If a person goes too many times . . ., you finally react.” He remembered a game called yampolke,25 which they played in that backyard, which involved hitting a stick on the ground with a larger stick and then hitting it again when it was in the air. He recalled hanging onto the backs of trolleys when he didn’t have money for the fare or when he was saving the money for a treat and thought he’d take a chance.

All was not to continue in this ordinary way, however. The Russian Revolution and its aftermath had a major impact on Eli and his family. Many Jews, inside Russia and elsewhere in the world, at first welcomed the revolution as an end to tsarist oppression. Eli remembered “excitement in the streets,” parades, people carrying red flags, singing the “Internationale,” calling out “‘Down with the capitalists, with the murderers, . . . with the tsar. [Long live] the proletariat, . . . Trotsky and Lenin. . . . We children were watching” as adults celebrated “the new regime of the proletariat [pronounced in the European way, with stress on the last syllable], and the eventual victory of the Communism.” Right after the revolution, however, Rostov-on-Don became a major battleground in the Russian Civil War. As Eli described it,

the tsarist army, or the White Guardians,26 . . . occupied Rostov-na-Donu. There was fighting going on, you could see dead people on the streets, dead horses, horses who died and killed by compression the people who were riding, and it was terrible. Then, then again fighting in a couple of weeks; the Red Army took over, and then again it went to the White. Several times the city changed the hands, till finally of course the Red Army was victorious, and they settled there.

At that time, Eli’s brother Maishe (or Misha, as he was known in Russian) was mobilized and taken into the White Army. Eli recalled the day he came home:

Early in the morning, we heard a bell, ringing. I came out first, and I saw there was an old-looking man with a beard and I didn’t recognize him, till finally it hit me that it was my brother Maishe. Seems to be, he escaped from the White Guardians army, where he was doing the telephone lines, taking care of the telephone lines, and he escaped; he deserted the White Guardian army. . . . He came back to our house. He was with a beard, and completely unshaven, dirty, with plenty of lice. And my mother cried, everybody cried.

And then there was the Red Army. Then again, attack, and this White Army started to attack Rostov-na-Donu. My brother decided, because he was a deserter, he was afraid they may catch him, and that would have been terrible, went to this, our ice cream parlor, . . . in the back room, . . . where he was hiding and covered himself with a lot of boxes and cans, they shouldn’t find him. And imagine, at that time when the White Guardians came, they were in the backyard of the store, but they didn’t open the [back room]. They were all looting. And what we did at that time, to make appear that it was looted already, we opened the front door, we took out and broke the windows. And he was hiding there, while the door was open, and therefore they didn’t touch anything, and they didn’t look in the back. Then finally the Red Army took over, and then he was able to go out of the hiding, and he became an ardent Communist. When we came back to Lithuania he didn’t want to go back. He wanted to stay in Russia.

Eli’s account of the preemptive “looting” of the house is reminiscent of similar actions taken by Jews, then and earlier, to avoid oncoming pogroms. Maishe (known as Misha thereafter, his Russian name) was at that time the oldest son at home with the family. They remained in touch with him at least until the start of World War II, and he remained an ardent Communist, at one point sending his brother Dave, in the United States, a photograph in the style of socialist realism (figure 11).27 The woman in the photo is unidentified, but she looks very much like Misha’s wife in a later image (figure 12). As I will relate, my father disappointed Misha when he decided to go to the United States instead of the Soviet Union after the Holocaust, but Misha contacted him again many years later.

Figure 11. Maishe (Misha/Moshe) Rochelson and a young woman (his wife or future wife) in workers’ clothing, reading Pravda. Family collection.

Despite early optimism among many, the Revolution did not bring with it the hoped-for better life. Times became harder for the family in Rostov, and they began to think about returning to Kovno. As Eli described it,

[i]t was difficult with getting food, it was . . . famine or starvation . . . all over Russia and in Rostov-na-Donu also. . . . We had to close our store there. [W]e couldn’t get supplies, . . . [and] the Russians were looking at any people who are enterprising as remnants of capitalism or capitalistic enterprises, and they just—we were afraid and we couldn’t get even merchandise. The only thing we could do, there was like a marketplace in Nakhichevan, and we, buying bread, let’s say, and selling bread, . . . we make profit to have for us at least a few slices of bread profit—bread—no money, but bread. Otherwise if you ate . . . [all] the bread we didn’t have money to buy it the next day. . . . [T]hen we also had thread, needles, little tiny things which we could sell. . . . But the Russians made many times, we called oblava [a raid], it means . . . they surrounded [us] . . . from all streets, and were catching those who were selling. They didn’t like even this, they didn’t want any enterprise, this already is the beginning of the capitalism. And to make the story short, they [had] rations, we starved. One day they would have dried fish, salty, the other day they would have salt, the third day they will have sugar, or peas or pea soup. That was all we could have, and we really starved.

Although summers in Nakhichevan could be hot enough for ice cream, the winters were extremely cold:

Now our house was heated with a stove, a coal-burning stove, and also wood-burning stove. Now we had to supply these. I and my brothers were going, and I had to carry, let’s say, I remember, a whole sack, a canvas sack, with coal I was getting, and bringing home, going for miles bringing home to have some for the coal stove; also wood we were getting, to keep warm. . . . [W]e didn’t have water [in the house]; in the winter, we had to go to a pump near the house . . ., and imagine there [it] is cold like in Alaska. . . . You go with a pail, and you go up and there is a hill of ice; you go up, you have your pail and you try to go down: Bingo! Everything spilled out and you go again and you bring it.

While in Nakhichevan, Eli caught the Spanish flu during the great epidemic of 1918–19 that killed between twenty and forty million people (“Influenza Pandemic of 1918”). The disease infected one-fifth of the world’s population, and was most deadly among people aged twenty to forty. Eli would have been between eleven and twelve years old: “I got sick; while in gymnasium, I had chills. . . . When I came home I told my mother I am very, very sick. She put me to bed, and I became delirious. The only thing I remember is seeing rats going over the chest across my bed, and various types of wild pictures, imaginary of course.” Some months later he became ill again, and an Armenian doctor treated him for typhus recurrentes, recurrent fever, and then for spirochete of Obermaier, a microbe causing “paroxysms of high fever that last five or six days” (Stevens 260). “[T]his Armenian doctor, really,” Eli recalled, “saved my life.” There was a cholera epidemic at this time, as well, and, as he recounted later, people were dying of cholera within twenty-four hours. But the government gave the family cholera immunizations, and they were spared: “I still remember the pain [of the vaccine],” he reported; “I had sharp pain with swelling of the arm, but this saved me against cholera.” Eli remembered these events in the interview as an adult and a physician, and he took pride in sharing the details with his son, who was about to begin his own medical studies.

With conditions worsening in Nakhichevan and relatives in Kovno urging them to return, the family traveled back, via Rostov-on-Don and Moscow, in 1921. Even today, that rail journey would take between seventeen and twenty-eight hours. Apparently many families were making the trip then; Eli recalled that children left the train when it stopped, and some did not get back in time. When his family arrived in Kovno—“so starved and so hungry”—they were greeted at the train station by an older cousin, Dora Ozhinsky (a sister of Genya and Riva Lubovsky), who brought hot chocolate, bagels, candy, and other treats: “Imagine what it meant to us. I still remember the taste.”28

At the time the family arrived home, Kaunas (Kovno) was the temporary capital of Lithuania, which had become independent from Russia in 1919. Vilnius (Vilna), the traditional capital, switched hands between Russia and Poland in the interwar years and was restored as the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic when the Soviets occupied Lithuania in 1940. It is the capital today, while Kaunas remains the second-largest city. At any event, Eli enrolled in the Russian gymnasium in Kovno, as he had in southern Russia. Most of the Jewish teenagers attended either the Hebrew or the Russian gymnasium, not the Lithuanian, in part because of the intense Lithuanian nationalism in those schools, which alienated Jews. Additionally, as Eli pointed out in the interview now in the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library, when Lithuania was part of the Russian empire, before the first world war, “[t]he Lithuanian language was strongly forbidden and you could be jailed for studying or teaching the Lithuanian language” (Rochelson, NYPL interview 4). Eli’s sister, as he mentioned, encouraged him to study Russian, and he had already received a good start in Shershevskii’s school. That he did not attend Hebrew gymnasium thus may or may not reflect on his family’s practice of Judaism, but it does suggest a desire to be part of the larger world. As Eli’s account makes clear, however, in the early years of the twentieth century he and his family were observant Jews, although not ultra-orthodox, and probably like most of their Jewish neighbors.

In the NYPL interview Eli elaborated on his own language use, and on general language preferences among Jews in Lithuania. In his childhood home they always spoke Yiddish, but when he was a young man and when he married, he and his Jewish peers conversed in Russian (4). Later in that interview he indicated that he also knew Lithuanian well (69). Thus there is a real parallel in language use as well as degree of acculturation between my father’s generation of Jews (at least those in urban areas), whose parents remained in Lithuania, and those of the same generation (for example, my mother), whose parents emigrated to the United States and other Western nations. Yiddish was their first language, but they were also fluent in the languages of the nations in which they lived. Modernity touched all of them, its course interrupted in Europe by the Holocaust. Those who perished and those who survived were as much a part of twentieth-century culture as those who built Jewish lives in American cities after the 1880–1920 great wave of immigration (see figures 13, 14, 15a, 15b, and 15c).

Figure 13. Avraham (Abraham) Rochelson (seated, left) and other members of the sport club “Ha-Koach” (Strength, Power) in a 1928 formal portrait. Family collection.

Figure 14. Chaye (Chaya/Anna) Rochelson Arendt and Albert Arendt visiting Montevideo, Uruguay, 1928. Albert had relatives in Uruguay. Family collection.

Figure 15b. Mottel (Mordechai) Rochelson, formal portrait, no date. Family collection.

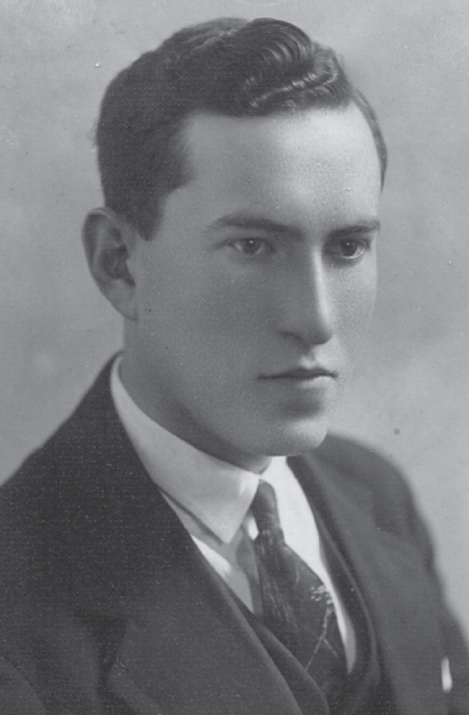

Figure 15c. Ilija (Eli) Rochelson, formal portrait, August 5, 1930. Inscription on the back reads, “From your youngest brother, Ilija, whom you used to carry on your shoulders” (translation by Rivka Schiller). Family collection.

When Eli and his family returned to Kovno, his studies in Rostov were accepted and he entered the third year of a gymnasium formed by “a cooperative of former Russian teachers . . . who were tsarist” and had fled the revolution.29 He described the curriculum, in which he also studied Lithuanian language and history, as including mathematics, geography, astronomy, general history, and German. Exams after the first four years of study allowed a student to go on to the fifth through eighth years. Eli remembered the German courses especially well, because they led to a high degree of mastery: “We already had to write about Goethe and Schiller, and even had to memorize certain things from Goethe. Heinrich Heine wasn’t allowed, but we were reading Heinrich Heine too.”30

When the family first arrived in Kovno from Rostov, they lived a semirural life, keeping two cows, a goat, and chickens in their backyard. The animals shared a pasture with those from several other houses and, as Eli told the story, each cow knew where to come back to at night. Once when he became ill he was given goat’s milk as a treatment—“[g]oat milk . . . and fresh air, and good food, and sweet cream, and cakes, all these carbohydrates. I think it was a good idea, too, after starvation.” They had chicken, eggs, and milk from their livestock; they made sour cream and butter from the milk, as well as cheese, straining the milk through a towel. They sold some of the dairy foods they produced and thus were able to make a living and eat well themselves. Later they moved to Slobodke (also spelled Slobodka, or Vilijampolé in Lithuanian), a place renowned for its yeshivas, places of Jewish learning. It eventually became the site of the Kovno ghetto, after the Nazis occupied the city. When Eli’s family lived there, he had to walk four or five miles, he estimated, across a bridge over the Neris River to the Russian gymnasium, summer and winter. He told this story in his interview with Burt, but he also told it to me often when I was a child. I was a bit surprised when I learned later that a parent’s tale of walking to school over ice and snow was also part of American childhood lore, that children with American-born parents would later joke about hearing similar stories of hardships in the “olden days.” In Eli’s case, he had to pay a toll to cross the bridge, and once he and his brother Mottel got into a fight with the bridge tender when they didn’t have the fee. In spring, when the ice melted, the bridge was washed away, and they would give someone a few kopecks to row them across, about ten people to a boat, each way. After Slobodka the family moved again, to the center of town, near a fish market, when Bere-Mikhel worked for the Wolf-Engelmann brewery.31

Eli completed gymnasium in 1927:

[W]hile in gymnasium, in the same class there was Misha Meerovich and his sister, Serafima. I fell in love with her; I was invited many times to her house because Misha Meerovich was my friend. We were talking together. . . . He was a very bright young man, a capable man, he was—he never prepared his homework, he knew when he was present at school, he remembered, he memorized, and he was, in all type of science, or literature, philosophy, he was very adept, he finished with high marks. His sister was also in the same class; we had, at that time, a co-ed school. Now, many times we were walking together, he was talking about Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche, and other things, and I would say, partly my education was also through him, and his education, he got from his father who was a pharmacist, a very intelligent, cultur[ed] man.

Mikhail (Misha) Meerovich was born in March 1910, making him nearly three years younger than Eli; Serafima was one year younger than her future spouse.32 That they were all in the same class attests to the high intelligence that Eli took pains to record (see figure 16).

About 30 percent of the students at the school were Jewish, 70 percent were non-Jewish, and Eli had many non-Jewish friends: “We were going out together, meeting each other, and there [were] no signs of antisemitism, or any hostility” at that time. Teachers, too, showed no hostility, and, as Eli remembered, “it was a very neat, close group together, . . . the students and the teachers.” In order to receive a “certificate of ripeness,” essential for applying to university, students had to pass difficult written and oral exams, at the latter of which a representative from the state education department was present. Nearly fifty years later, Eli recalled how his German teacher, named Pinagel, was surprised that after his excellent performance in class his written exam was not satisfactory. She apparently then graded his test generously, so that he would gain the certificate, and then examined him orally again to make sure he knew the material. In the end, he graduated cum laude.

Figure 16. Graduation photograph, 1927, Kovno Russian Gymnasium of the Teachers’ Association. Eli Rochelson’s picture is on the extreme right of the third row from the top; Serafima and Mikhail Meerovich are second and third from the left in that same row. Family collection.

Antisemitism existed, however, in higher education. Eli applied to the veterinary faculty of the University of Vytautas the Great (also known as Vytautas Magnus University) in Kaunas, “because I knew they wouldn’t accept a Jew in medicine.” After a year, however, he applied to the medical faculty and was accepted. He had to earn a living, as well, and he worked as a bookkeeper while taking one course each year, presumably yearlong courses. There was no time limit, as long as he paid tuition. When he was drafted into the Lithuanian army in 1935, his wife took over the bookkeeping job and he took six weeks off from his medical studies for basic training. Photographs show Eli in his army uniform and with his unit in the snow; he would explain that he was the one wearing a fur collar because they had to keep the doctor healthy (figures 17 and 18). Some of the young army doctors (jokingly?) practiced their trade for the camera indoors (figure 19). In his interview Eli praised an encouraging colonel, “the doctor in charge of the [military] hospital,” who told him that, for the year and a half of service required after the first six weeks, he could work in the hospital in the morning and then “take off your uniform and go to medical school.” Eli did that, and by 1939 he had finished his military service and earned his candidacy in medicine; in 1940 he received his medical degree.

As with the colonel, Eli took pains to acknowledge the non-Jewish teachers, professors, and even a dean who showed him friendship and support as he pursued his education. Similarly, he spoke of the friendships he had with non-Jewish peers, especially up until the early 1930s. He wanted to explain the complexities of life in Lithuania, as well as its pleasures. It was important to him, and valuable to his story as history. Seven decades after the Holocaust ended, it is too easy and at the same time inaccurate to see the situation of the Jews in their East European homelands as an unremitting struggle against antisemitism. Yet Eli also exposed the antisemitism that he and other Jewish medical students suspected and encountered:

Figure 17. Eli in the uniform of the Lithuanian army, January 1937. Family collection.

Figure 18. Eli (front row, third from right) in his military unit, February 1937. On the back he has written in Yiddish, “Not far from the shooting field. People are warming themselves by the fire. I am standing in the fur” (translation by Rivka Schiller). Family collection.

Figure 19. Army doctors with their patients, February 1937; Eli is at far left. Family collection.

We had eighteen subjects, and each time you had to pass [an] oral examination, and face the professor. I had an argument with the dean of the medical college, he was the professor of physiology. Each time he failed me. I had to go two or three times; he said, come in a month, come in a month, and in a month. At one time—and the people, usually the students were waiting outside, and [there] were one or two—inside he questioned, and the other[s were] outside. One time he said, you come in a month; I got mad, and slammed the door, and then he said—they told me after, a girl, a medical student told me—“You know, he made a remark about you, he said you got mad, he almost broke the window, but I will never let him finish the medical school.” Of course I got upset and so on, but finally I passed with him the physiology.

Anatomy was a different chapter. The first year of medical school we had one part of anatomy, and the second year we had the second part of anatomy. We had to do all colloquiums, about thirty-six colloquiums. . . . [T]his professor, his name was Yelinski, he was a known antisemite, and people were going, couldn’t pass from first year, many times, and to the second year, or from second year to the third year, because he wouldn’t pass [them in] the examinations. And the Jewish fellows sometimes go three or four years, studying only anatomy to pass. But he was such a cruel man, that after you answered all questions, he says—[he] gave another question. If you didn’t know: come in six months, come in three months. Anyway, one young student, already three or four years, and he didn’t pass, he told him to come in three months, he jumped at him with a knife, and he wanted to kill him. But then the assistant Kropotky came out. And I was then in the building there, nearby. He came out and he saved his life. But the man [the student] was committed to an insane asylum where he committed suicide. And that was only an illustration how hard it was in Lithuania, especially when you are a Jew. I think Lithuanians, the natives, didn’t have too much problems; they have their notes in Lithuanian language, whatever they had, and they passed them immediately.33 It only was trouble with the Jews. Anyway, I overcame— . . . This man who attacked the professor was not crazy, he was just mad and he couldn’t suffer anymore. That was the story.

Natalia Aleksiun, in research on Jewish medical students in prewar Poland, has found similar antisemitism toward Jewish medical students there, and specifically among professors of anatomy (see Aleksiun, “Christian Corpses for Christians!” “Jewish Students and Christian Corpses”). Šarūnas Liekis reports that, on December 12, 1939 (just months after Eli received his candidacy for the degree), “[t]he [non-Jewish] students of the Kaunas University medical faculty started to protest and to demand to establish numerus clausus [numerical limitation, or a restrictive quota] for the Jewish students. The Lithuanian students filed a written complaint stating that the Jews were not loyal to Lithuania and claimed that Jewish students were distributing leftist literature” (254–55, italics in original). The University of Vytautas the Great medical school was later known as the Kaunas Institute of Medicine, or the medical faculty of Kaunas University (figure 20).

Figure 20. Entrance to Kaunas Institute of Medicine in 2003. Photograph by author on visit to Kaunas.

![]()

1. Scholars of these turn-of-the-twentieth-century communities sometimes denote the geographic boundaries between Litvaks and Galitzianers (the other major Jewish cultural group in the region, largely in Poland) with a “gefilte fish line”: east of it, Litvak Jews preferred their gefilte fish savory; west, the Galitzianers preferred it sweet (see Prichep).

2. Recently, doing research at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, I discovered that my father’s intake documentation from Dachau lists his date of birth as 1907.IX.1—September 1, 1907 (Dachau questionnaire of Ilija Rochelson, Individual Documents Dachau, 1.1.6.2/10266519_0_1/ITS Digital Archive. Accessed at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum on January 23, 2017). It is repeated on some, but not all, of the cards in his International Tracing Service (ITS) file, perhaps because the relatives searching for him used his traditional birth date.

3. The perpetual Jewish Civil Calendar, http://wwwx.uwm.edu/cgi-bin/corre/calendar, is an extraordinary resource. There is now, of course, an iPhone app that also makes the conversion. I am grateful to Dr. Galina Baranova, now director of the Lithuanian State Archives, for providing me with copies of vital records documents, while I waited, on my last day in Vilnius.

4. This information is now in the Lithuania births database on JewishGen: LVIA/1226/1/2013.

5. I am deeply indebted to the genealogical work of Francis (Bob) Wilson, George Rockson, and Eric M. Bloch, whose combined efforts produced a detailed and comprehensive family tree on which I have relied while writing this book, and who compiled the extensive family history from which I have learned so much. I have also relied significantly on the All Lithuania Database of JewishGen.org, compiled through the efforts of LitvakSIG researchers who have translated and posted an extraordinary number and variety of records online. Spellings of names and specific dates can vary from item to item, as they still do in our supposedly more accurate age. I have tried, wherever possible, to indicate the sources of this information in the Kaunas Regional Archives (KRA) and the Lithuanian State Historical Archives (LVIA), as indicated in JewishGen and LitvakSIG documents.

6. JewishGen Tax and Voter Lists, KRA/I-222/1/2/134; see Bloch, “Rochelson Family History,” endnote 16. Eric Bloch more recently brought to my attention, from the Kaunas Research Group databases, that Eliash Rokhelzon (another spelling of the name) had five hundred rubles in property in 1892, making him one of the wealthier Jewish property owners in Veliuona at the time (KAU-VEL-1892 Box Taxpayers List, Kaunas Research Group of LitvakSIG; e-mail to author, August 26, 2017).

7. Mihkel Ber’s date of birth is in the All Lithuania Revision List Database, Part I, of JewishGen, Family List KRA/I-197/1/1. For Henye’s most likely year of birth, see internal passport record KRA/66/1/738; dates in the JewishGen records differ.

8. See articles on “Shaki (Sakiai)” and “Naishtot (Kudirkos-Naumiestis)” by Joseph Rosin.

9. In Yiddish names such as this one, which end in an e, the final letter is pronounced as a separate sound, something like a short i in English. The sound is more obvious when the final e follows a y, as in Henye or Genye/Genya, which are variations of the same name.

10. Greta Minsky, e-mail message to author, April 26, 2017.

11. My son, then in elementary school, had been assigned the task of interviewing an elderly relative. He chose Uncle Dave as the oldest person he knew, and I was amazed and delighted at this story from a past I had never imagined. Uncle Dave died on July 19, 1993.

12. The Yiddish names of the family are derived from Hebrew names. Chaye is a version of Chaya, meaning life, and can be translated to English as Eve, although my aunt’s European name was Anna; Maishe (also Mishe or Misha) is Moshe, or Moses; and Mottel (also known as Motteh) is Yiddish for Mordechai. My father’s name of Ilija is Eliyahu, or Elijah.

13. Chaye died from complications of this disease, as I will discuss in its place. According to a birth record in JewishGen (LVIA/1226/1/1993), the sister who died in early childhood was named Gitel.

14. This is the word for hostel in modern Hebrew.

15. Also spelled Feige or Faige, Leya or Leah, Taube, etc. Although spellings of names may be inconsistent in the narrative, I hope the reader will understand. All of these names were originally spelled in Yiddish, in Hebrew letters.

16. See the family diagram in appendix B. Uri Kanter made aliyah to Israel, probably in the 1930s, and his family survives there.

17. Dov Levin lists the dates of the expulsion from Kovno as May 2–5, 1915; if these dates are according to the Julian calendar, then the dates in the rest of Europe would have been May 15–18 (see Levin, Litvaks 107).

18. I am grateful to Josef Griliches for identifying this town east of Kovno, nearly halfway on the road to Vilna. Its Lithuanian name is Žiežmariai.

19. I have not found additional information to confirm two orders, but this was Eli’s recollection.

20. This route would have taken the family southeast from Kovno, through what are now Belarus and Ukraine.

21. These are items and rituals associated today with Orthodox Jews. A payah (pl. payot, or payis) is the lock of hair that remains unshaven or uncut on the side of a man’s or boy’s head. Tzitzis (or tzitzit) is a word that means fringes and refers to the fringed garment worn by men under a shirt, generally with the fringes visible. Tefillin are known in English by the equally obscure word phylacteries. They are small leather boxes containing words of scripture that remind the wearer of the commandments. They are worn at weekday morning prayers, affixed to the head and arm by narrow leather straps.

22. Church Slavonic, the script of which differs from the more modern Cyrillic alphabet.

23. When my son was in high school, more than eighty years later, we hosted an exchange student from Azerbaijan. Alex mentioned to us that his family had lived for a while in Rostov-on-Don; what he remembered most about it were the ice cream shops.

24. The Russian gymnasium was a high school, but students started to attend earlier than in the United States.

25. The name of this game may be derived from the Russian word yama, which means hole or pit. In the interview Eli explains that the smaller stick was placed on the ground on top of a stone.

26. This group of anti-Communist forces is more commonly known in English as the White Guards.

27. The photograph is signed by Misha on the back, and dated/3/VIII/25 (3 August 1925).

28. Dora Ozhinsky and her sisters were the children of Henye Rochelson’s brother, Mordkhel Lubovsky. According to Riva’s grandson Pierre Pizzochero, Dora, Genya, and Riva also had a sister Essia and a brother David. David was killed in the action against intellectuals in the early days of the Kovno ghetto, as I will discuss, and in an e-mail Pierre confirmed that Dora (and, most likely, her children) was also killed in the Holocaust. Essia, however, had married a Russian and survived the Holocaust in Russia. She had a son who became a scientist and a professor at Lomonosov Moscow State University. As I learned from Pierre in conversation, Essia visited Riva and Genya in Milan, where they lived sometime before their deaths, and the sisters enjoyed a few weeks’ reunion. As I will discuss, while researching this book I came in contact with other Lubovsky cousins, the Esner family, American descendants of a sister of Mordkhel and Henye of whom neither Pierre nor I had previously been aware.

29. Josef Griliches identifies this school as the Russian gymnasium that was near a Russian Orthodox church, on Vytauto Prospect in the eastern part of Kaunas. There were also Polish and German gymnasia nearby (telephone interview, October 2012).

30. Heine, a German poet of Jewish birth who converted to Christianity, was well known for his lyric and his satiric poetry, as well as his sometimes radical political views. He was a key poet studied by Jews at this time, as well as by others. His own relationship to Judaism was complicated, and that, too, was part of his identity for Jewish readers.

31. Volfas Engelman brewery, now largely owned by a Finnish company, was in the 1920s also called Wolf-Engelmann. At that time it was responsible for 40 percent of Lithuania’s beer consumption (“Volfas Engelman”). A Volfas Engelman beer is apparently still distributed by the Ragutis company based in Kaunas. The original Wolf Engelman was a Jew, and in 1940 the brewery owned by that “Zionist leader” was confiscated by the Soviets (“Soviet Seizes Jewish-owned Brewery”).

32. Misha’s birthdate is recorded in a Kaunas draftee list, KRA F 219/2 1043, made available to subscribers to the Kaunas District Research Group of LitvakSIG; Sima’s year of birth appears in the internal passport database of LitvakSIG, Kaunas District Research Group and JewishGen, KRA/66/1/40515, passport number 68/2603.

33. According to Paulina Rosenstein, whose mother graduated from the same medical school, the language of instruction and the textbooks were in German. (Personal conversation, January 24, 2015.)