Our country has always celebrated the individual; it is the very essence of what it is to be an American. That’s what I grew up believing. Whether it’s in the arts, science, or industrial innovations, the United States has paved the way for countries around the world, and has acted as a beacon for individual thought and freedom. As I said, my grandfather moved us to Astoria, Queens, for the uniqueness and diversity of the community, so I was always encouraged to be myself. In fact, we were discouraged from copying people around us.

When I was a young boy, I used to go to the movies and watch Fred Astaire on a Saturday afternoon. I’d walk home dazzled by the way he performed. He was a jazz dancer; he never repeated himself. In every movie, he made it a point to do something unique. On top of that, everything he did was different from anything anybody else had done before him.

Early on, I learned the importance of not copying other people’s style. I had a great voice teacher, Mimi Spear, whose office was on Fifty-Second Street. That block looked like some little alley in New Orleans, right in the middle of this huge cosmopolitan area. The awnings lining the street advertised the likes of Art Tatum, Billie Holiday, Stan Getz, Lester Young, George Shearing—all there in those wonderful clubs. “Don’t imitate another singer, because then you’ll just be one of the chorus,” Mimi told me. “Instead, listen to jazz musicians that you like, and find out how they do their phrasing.”

So I listened intently to the musicians, and I absorbed as much as I could from them. Fifty-Second Street was a haven for all the greats. You could just roll into those little clubs on any day and witness magic. This was the age of jam sessions; when the acts were done performing at 3 a.m., they’d close the doors and keep playing until noon the next day. As a young man, after listening to hours of Miles Davis and all these other incredible players, I’d walk out with my friends from a pitch-black room into the glaring sunshine. I can’t figure out how we functioned on so little sleep, but it was all worth it. I remember listening to Lester Young, “the Prez.” His sound was so sweet and so new that I got physically sick from excitement. I absorbed the unique phrasing and breath control of masters like Young and Stan Getz in order to hone my style.

When I started playing with bands, I would try to be individualistic and improvise. They’d be in a dance tempo, and suddenly I’d do something entirely new with the beat. Musicians used to ask me, “What are you doing?” They’d criticize me for not keeping the beat, since it was all about getting people up to dance. “I’m being different. That’s the way Art Tatum phrases,” I would tell them. So I took Art Tatum, and Stan Getz, who had a beautiful honey sound on his saxophone, and I applied their music to my singing. It was the beginning of my finding my way musically and developing my own style.

Jazz is in the moment; it’s Zen-like. It never feels tired, because it’s full of vitality. Jazz is the most exciting and creative music there is. It reminds me of a sketch, rather than a premeditated painting. There’s nothing greater than a Rembrandt sketch; with just a few lines, he could draw the leaves on a tree, where you can almost feel the wind blowing through them. That’s what jazz is all about; it’s a spontaneous moment that you’re capturing.

Today, though, a lot of this has been sucked out of the music that’s made. It seems as if everybody has to sound the same and be the same. The record labels find out what sells, and they force all of their artists to conform to whatever that sound is. Instead of celebrating someone’s unique character, we applaud the ability to conform. People feel they have to wear certain labels on their clothes and all look identical. This tendency has been a result of marketing companies’ promotions, and unfortunately, it has brought us to a new low.

When I grew up, even though it was the Depression, people were respected by their fellow Americans for their individual spirit; for just being themselves. Of course the big corporations felt differently, and felt threatened by independent thinking, as they do today. If you made it, you made it because you were different from the next guy. Nowadays, it’s all been flattened out.

Back in my day, you knew the difference between Art Tatum or Erroll Garner or Teddy Wilson just by listening to them. If you heard all the instruments together on a song, you could tell who the great trumpet player was. You’d say, “That’s not Roy Eldridge; that’s Ziggy Elman.” But today, even jazz has been cursed by elevator music. So you hear a sax with a trio, and they all sound alike; you can’t tell if it’s a Ben Webster piece, a Coleman Hawkins, or a Charlie Parker, because the producers have congealed music into something shapeless.

Greed has corrupted the process as well. The music has stopped being art, and for many it’s become just a way to make a lot of money. But time has proved this to be the wrong path. Not a day goes by when you don’t read in the papers that the music business is in decline. The funny thing is that I’m selling more records now than I ever have, when everyone else is complaining that he can’t get a break. So I figure I must be doing something right.

Ever since the fifties, I have sung a certain way; I’ve strived to be myself, and that has always worked for me. I never went where everybody else went. When we started working together, I told my son Danny, “No matter what we do together, when everybody zigs, I want to zag.” That’s always been my philosophy, and Dan has done an excellent job of making sure that we stick to it. If everyone is going one way, we go the other way.

Toward the end of the sixties, I learned the importance of knowing when it’s critical to take bold steps to leave the comfort zone, move on, and take chances. I was going through hard times on the domestic side of my life, and had recently been divorced from my first wife. I was remarried and had moved to Los Angeles, living far away from New York City for the first time, which was a big deal for me.

Eventually, after my battles with Clive Davis at Columbia Records, I decided it was in my best interests to leave and start my own label. After moving to London for a complete change of scene, I created my own label, which I called Improv Records. For the first time in my career, I had complete artistic freedom to record whatever and with whomever I wanted. It was a very ambitious venture for that time; going independent was not in fashion then as it is today. The actual business logistics were quite challenging. In fact, this was the first time I asked my son Danny to help me out on a professional level, which as most people know, led to our working together for over thirty years, with untold success.

Dan was working in bands and following his own talents as a musician, but he always showed an interest in the business side of music as well. He reviewed the label contracts for me and pointed out how distributing records without a major label behind you could be problematic. I asked him to advise my partners of his concerns, but they unfortunately didn’t take him seriously. I decided to move forward, as I was excited about the prospects of creating albums that I had long hoped to produce.

One of those dreams was to record with the great jazz pianist Bill Evans, an idea suggested by Annie Ross. With all the albums I’ve made, the two that I recorded with Bill are considered my most prestigious. In the jazz world, Bill was known as a genius. Nobody in the world has ever played piano like Bill; it was unbelievable. We reached out to his manager and longtime producer, Helen Keane, and struck a deal in which we would record two albums’ worth of material. The first, The Tony Bennett/Bill Evans Album, would come out on his small jazz label, Fantasy Records. The follow-up album, Together Again, would be released on my Improv label.

Unfortunately, his company was quite uncreative in marketing the album; they put it out without doing any promotion, and the sales weren’t very strong. But realistically, it’s the best thing I ever did. I produced the best music with the best piano player, Bill Evans, and the greatest orchestrator in the world, Robert Farnon—and now those albums live on in The Complete Collection box set of all my albums.

I’ve learned that it often takes five years for something to catch on, and that’s what has happened with those records. Sometimes you just have to believe in yourself and exercise a lot of patience. Unfortunately, Improv folded as a result of my business partners’ inability to meet the challenges I mentioned, but I remain proud of the music I made during that time, and it continues to endure. Through the experience, Danny had given me some sound advice, which I would later tap into. From the day we started working together, we never looked back, and we’ve achieved some groundbreaking accomplishments that I’m very proud of. So it just goes to show you that sometimes you have to know what to leave behind in order to move forward.

I try to be inventive when I’m performing or recording. The producers can never figure out what I’m going to end up doing. It’s frustrating for them because it’s not easy to categorize me; all of a sudden I’ll sound different from the last recording, or what they expected or wanted from me. Strangely enough, I’ve never had trouble with the public on that front; they just enjoy what I do. But I’ve been misunderstood by a lot of producers and record label people. I never intend to be difficult, but I always have a clear sense of what I’m trying to accomplish. I always strive to be an individual.

Ever since I started performing, I’ve always wanted to put my best foot forward, and that carries over to the way I dress onstage. I think it shows respect for the people who’ve gone to the trouble to come out and see me perform.

I was watching television at 2 a.m. one night when a documentary about Andy Warhol came on. It caught my interest because I had known Andy pretty well. They were asking him about changes in society and the fact that no one wears a suit any longer. The speaker asked him, “Is there any glamour left?” and Andy said, “Yeah.” All of a sudden there’s a picture of me with Andy at a Hollywood party. “Tony Bennett’s the only one keeping it with the glamour,” Andy said.

I’ve been in three earthquakes, and one was in Japan with Count Basie’s band. It lasted for an entire minute, and the band ran out into the street in the middle of the night. Funny enough, I slept through the whole thing, and the band kidded me for the rest of the tour because I missed it. I was lucky it wasn’t a bad one.

But the earthquake I’m known for was a big one in Los Angeles. The whole chest in the bedroom came down with the television on it and everything; it went bam! right next to my bed. It was four o’clock in the morning, and my hotel was evacuated. I went outside, and there was everybody in their pajamas and bathrobes. I was the only one who’d put on a suit. Most people were shocked, and asked me if I slept in my formal wear. When a reporter interviewed me about the incident, he asked why I had a suit on in the middle of the night. I said that it was because I was voted Best Dressed Man that year and had to live up to that image. But, joking aside, if you respect someone and also have strong self-respect, you’ll take the trouble to look your best. Putting that extra effort into my appearance translates into showing that I care about what I do—and the audience picks up on that.

Speaking of zigging and zagging, Lady Gaga looked fantastic when she arrived to record “The Lady Is a Tramp” with me. She came dressed to the nines in a beautiful full-length black lace dress, and her hair was a striking shade of aquamarine. Gaga is someone who is not afraid to be different, and who has built a whole career around that. We realized we have a great affinity with each other on this front. When I told her that I loved the way she looked, she said, “Thank you, Tony. I thought I’d give it a little twist for you. I said, ‘What would Tony want?’ ”

Then she told me I looked handsome, and wanted to know if I chose the yellow shade of my glasses intentionally. When I told that her I did, she gave me a knowing look of approval and said, “I figured.” She could tell exactly what I had in mind.

Gaga was also intrigued by my past; she asked me what it was like with the girls when I started out. She wanted to know if they got nervous and started blushing around me like she was; she was imagining what it must have been like when I was a young pup. “I would’ve been chasing you around in this dress,” she said, which made me feel quite flattered. Lady Gaga was a joy to work with; she came to the session totally prepared, and the chemistry between us was all sparks.

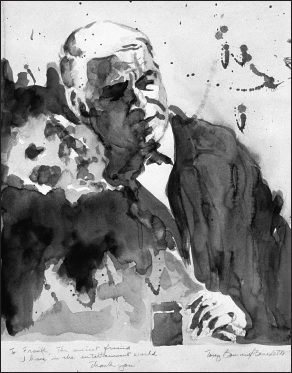

Later I painted Gaga’s portrait for a photo shoot for Vanity Fair with photographer Annie Leibovitz behind the camera. She was a natural model—and I’ll tell you, she was as professional and elegant undressed as she was dressed. We had a lot of fun together, and we have since become great friends.

“Vive la différence,” I love to say. Hanging out with people who aren’t exactly like you keeps life interesting, and also keeps you on your toes. Andy Warhol once told me: If you have an idea, but you don’t execute it, then it’s just an idea. But if you do it, then it becomes a fact. That statement always stuck with me, and spurred me on to try new things. I’m always seeking to find new meaning in a song, every time I sing it.

I’m very satisfied when one of my songs comes on the radio and people say they can tell right off the bat that it’s one of mine. Then I know that I’ve done what I set out to accomplish. If you strive to be yourself at all times, you’ll just naturally be different from the pack. Remember that no two snowflakes are alike!

The Zen of Bennett

Don’t imitate another person, because then you’ll just be one of the chorus.

If you create good music, no matter what year it came out, it will always sound completely modern.

Use the past to memorize the mistakes you’ve made, and make sure you don’t repeat them.

When you are yourself, you automatically become different from everyone else.