8

To Kill a Witch

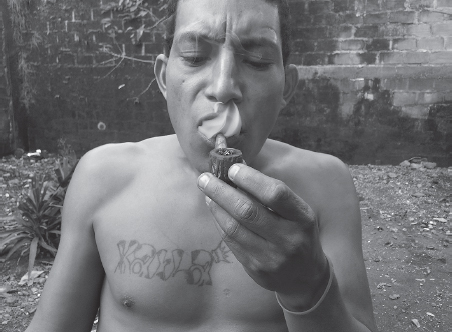

Even from outside Miguel Ángel’s shack, you can smell the penetrating scent of pot. The air is so still that the smoke lingers, hovering above our heads before slowly dissipating into the blue sky of western El Salvador. The police at the outpost across the street ignore the spectacle. They’re used to it. Inside the shack, on this January day of 2012, Miguel Ángel is smoking a joint as fat as a finger. He offers us a brief, hoarse hello, wanting to hold in the precious fumes as long as he can. He speaks and inhales, lets out a little smoke and then sucks it back in, swallowing back the gulp that had started to pour out. He’s enjoying himself so much that just seeing him makes you want to take a puff, to relish the dense smoke as much as he does.

Lorena, his teenage wife, is washing Marbelly in the cement sink and preparing a weak, translucent coffee. Something’s cooking in a pot, smelling spicy and healthy. At first glance, this could be the home of any young campesino couple.

Miguel Ángel wasn’t expecting visitors. When he knows people are coming, he puts on an old button-down shirt and shoes, and skips the marijuana. Today, he’s barefoot and shirtless, wearing threadbare pants. His hair is mussed, his eyes are red, and his mind is full of smoke.

He wasn’t expecting visitors or an interview, but stories are crowding on his tongue, and he’s ready to tell them to anybody willing to sit and listen. When he begins to talk, however, a battle begins between the stories he wants to get out and, maybe more important, the smoke that he wants to keep in. It’s like listening to someone trying to stifle a coughing fit.

When Chepe Furia first arrived, in 1994, Miguel Ángel had already tried to kill several people, but he’d only succeeded with two: a kid he left dumped under a pile of branches next to a river and an old man. The latter meant almost nothing to Miguel Ángel. He wasn’t going to waste much breath talking about him in the shack. The old man wasn’t a gang member, and his death didn’t count for anything, didn’t earn him any respect. It was like scoring a goal against a team without a goalie, when there’s not even a game going on.

Precious smoke. Miguel Ángel enjoyed few things more than a pipe of marijuana and cultivating cannabis on the site where he lived as a protected witness.

The victim was an elderly goatherd who’d crossed paths with Miguel Ángel when he was still a boy. The goatherd, who knew Miguel Ángel as a bum and a thief, offered him a drink of Cuatro Ases. Miguel Ángel took a swig. The old man then said that he’d give him money if he let him “treat him like his wife.” Miguel Ángel said sure, and when the man celebrated by tilting back the bottle of Cuatro Ases, Miguel Ángel punched him hard, right in the middle of the chest. The old man fell backward to the ground, and landed flat. He struggled to get in another breath.

“He choked because I whacked him with everything I had. And you know, if you get hit when you’re drinking, you drown,” Miguel Ángel says while examining the roach of the joint between his fingers, deciding on the best way to inhale the last of it.

The young Miguel Ángel snatched the bottle of Cuatro Ases and stole a few coins from the old man’s pocket, watching him as he choked, or at least that’s what he thought was happening: that the old man, beaten up by years of drinking guaro, died right at his feet. That was the last Miguel Ángel saw of him: laid out, eyes closed, not seeming to breathe, and not having been able to treat the Kid like his wife.

Along with the poverty and violence he suffered, the criminal life first left its mark on Miguel Ángel when he was still just a boy. From that day on, after killing (or attempting to kill) the old herder, he was filled with terror every time he heard the tinkle of goats’ bells. He thought the bells were the soul of the old man following him around, looking for what that young kid still owed him.

The goatherd—a regular figure in the village—was named Chepe Toño. Memories, especially memories more than two decades old, tend to dissipate like puffs of marijuana smoke, but Miguel Ángel has hung onto a crisp image of the scene: one hard punch and the old man was dead. Later, in El Refugio, the other kids would tease Miguel Ángel by chanting: here comes Chepe Toño!

In any case, that murder didn’t count as a gang murder. It didn’t add a point to his name, at least not as the homies counted them. It wasn’t the kind of kill Chepe Furia wanted from his lost children.

Marbelly is fresh-faced and dripping wet from her bath. It won’t take long, however, before she’s rolling around in the dirt again. Miguel Ángel pinches what’s left of his joint between his fingers. A small ember glows between his lips. He burns himself and then finally tosses the butt. He spits ash off his tongue. Spits again. And then he starts to tell us about his first murder as a member of the Mara Salvatrucha 13, as a soldier for the Beast, as part of the tradition of assassins that began thousands of miles away from this little shack, in a strange land called California.

The Witch

By mid-1996, Chepe Furia had successfully planted the seeds of his gang. It was nothing like an established and structured mafia, but just a group of kids and teenagers bewitched by an older and more intelligent leader. They were ready and willing to do whatever Chepe Furia told them. After all, they had no one to tell them much of anything else. Soon it was Miguel Ángel’s turn to make a pact. To seal in blood his agreement with the Beast, he would have to kill in her honor.

Mara Salvatrucha 13 has a good memory. Its horrifying past has become part of its structure. The young gangsters learned to imitate what they saw, learned how to make it their own.

Years back in Califas, when they were still inspired by Black Sabbath, the gang started to play the Sureño’s bloody game: requiring new members to make their first kill. The Mara Salvatrucha 13—the Beast—taught her children what she’d learned. Meting out death is the price of admission, the seal of total submission.

Miguel Ángel’s first true hit was a baker. A youth from a small village, El Zapote, who, just like Miguel Ángel, was seduced by the irresistible ideas exported from the north along with the deportees. He was an Eighteen. Exactly what Miguel Ángel had been waiting for. After months of walking with the Beast, finally he had a chance to make a blood offering and become one of her legitimate children.

As leader of the mission they sent El Hollywood, a teenager with experience whose job was simply to make sure everything went smoothly, to be witness to Miguel Ángel’s initiation. They carried a 9mm pistol—a luxury for the neighborhood gangs, who still wielded machetes for whenever they were forced to carry out makeshift, artisanal hits.

Pop.

El Hollywood took the first shot, hitting the baker in the chest, knocking him to the ground. But then the pistol jammed. The baker, back on his feet, took off into the coffee fields, hoping to hide in the undergrowth, but that was precisely where Miguel Ángel was waiting for his opportunity. He hacked him with a machete in the face, and then in the chest, and then again in the face. The baker had stopped moving, but Miguel Ángel didn’t stop. He grabbed the baker by the hair, raised his machete again, and sank the blade into his neck. When El Hollywood arrived, with his pistol still jammed, he found Miguel Ángel staring into the eyes of a decapitated head. He was still holding it by the hair. Right in front of his face, the face of death. He dealt the head a couple of kicks, and a couple more kicks to the headless cadaver, and then he and El Hollywood lost themselves among the coffee trees.

At twelve years old, with a machete for a weapon, Miguel Ángel sealed his pact with the two letters.

“They said the guy was a witch, and it was true, because I tried with that pistol afterward and no problem, a fucking good shot. And then later again with the same gun … thunder, man. So that’s why I cut the dude’s head off, because they say that witches can put their brains back together. When El Hollywood came over, he found me holding the head,” Miguel Ángel would tell us in his shack, seventeen years after decapitating his victim.

The two boys ran through the coffee trees until they reached a field. They took a path to Miguel Ángel’s house, where they rested a while. Covered in blood, they burned their clothes and scrubbed their shoes.

El Hollywood ran to tell Chepe Furia and the other gangsters that the mission had been a success. The Beast had birthed another son. Now all that was left was the formal act, the ceremony. The jumping-in. The thirteen-second beating.

But being a teenage assassin, Miguel Ángel was worried about two things: the first was that his dad would find out about the half-bottle of Cuatro Ases he’d stolen and drunk with El Hollywood to calm their nerves after the decapitation; the second was that if they jumped him in during the week, he’d get in trouble at school for being all bloody and dirty and in trouble at home for ruining his uniform and his best pair of shoes. These were his childish fears.

Chepe Furia, like a kind godfather, soothed his disciple’s worries. He decreed that the jump-in would be the following weekend so that Miguel Ángel wouldn’t have any issues at school. These are the decisions you need to make when you’re the leader of a pack of teenage killers.

The clique at that time, Miguel Ángel recalls, consisted of twenty-two members.

Miguel Ángel’s life is cyclical, and he returns to his origins again and again, tying his life to the lives of other men who have been just as deprived as him, who’ve also bled and suffered in this part of El Salvador. They decided to jump him in on May 3—a sacred day for the indigenous community, a day of celebration for the god Xipe Totec, the Flayed One. The Flayed One is the god of rain and harvests, the god who restores life after his own death, who skins himself in sacrifice in order to restore the life of others.

In his capacity as founder and leader of the Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha de Atiquizaya, Chepe Furia directed the jump-in. In this performance of power, everything has its place. Chepe handpicked three established members to give Miguel Ángel his initiation. He made sure to assume a role in which he’d be able to keep his hands clean. So Chepe stood on the sidelines and slowly counted to thirteen as the fists and kicks rained down on Miguel Ángel. Chepe was the conductor of an orchestra, and the symphony was a beat-down.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep termed certain symbolic actions “rites of passage.” He described ritualized moments in which a person passed from one social category to another, abandoning all that pertained to his earlier life as he entered into a distinct social position.

One … two … three … Seconds lingering in the air, seconds as long as days. Chepe counted slowly. Thirteen seconds never last as long as they do for the Mara Salvatrucha 13. Marijuana smoke floating above the ritual, bottles of Cuatro Ases at the ready to bid welcome. The other members stood in a semicircle around Miguel Ángel. Kicks. Punches. The crunch of bone. Four … five … six … Outside of the semicircle were the second-class spectators, the other neophytes who would soon get their own turn to be pounded. The rite of passage always follows the same form, according to Gennep. Seven … eight … nine … Miguel Ángel was quick. With the agility of a cat, he was able to dodge most of the fists. He sparked one way and then the next. He covered his head. And then Chepe Furia stopped counting. “Three more, change over,” he ordered. Three fresh kids stepped in. Kick, kick, kick. Rib crunch, blood, airless lungs. Ten … eleven … Symbols are important, Gennep wrote. They give the ritual meaning. Twelve … gasping … thirteen. “Alright, dog, welcome to the Mara!” Chepe Furia announced. He offered his hand to Miguel Ángel, who, hearing the magic number, fell to the ground, to the dirt. All the other homeboys raised their hands and signed the Salvatrucha horns. They welcomed their new brother, congratulating him: “¡Órale!”

“I was hallucinating. My whole face was swollen, and I could feel a cracked rib. But Chepe Furia gave me his hand, and then I felt like I was a part of something really awesome,” Miguel Ángel would remember eighteen years later. He had been jumped into what would be his family for the next thirteen years.

With rare exceptions, you don’t get to choose your first gang name. Your new name is picked by the group. And it’s usually unflattering.

Miguel Ángel has a clownish face, with an outsized mouth and eyes slightly farther apart than normal.

On May 3, 1996, as people across El Salvador were sticking crosses in the ground to commemorate the Cross of May, Miguel Ángel Tobar died and a new man came to life. The newest member of the Mara Salvatrucha: El Payaso, or the Clown of the Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha.

Xipe Totec, Our Lord the Flayed

Xipe Totec was a popular precolonial deity worshipped from what is today El Salvador to Central Mexico. The legend goes that at the beginning, when the first humans came into the world, Xipe Totec took pity and offered them his own skin for sustenance. This is why corn is associated with renovation, with the death that gives us life. Something must die so that something may live and thus, in an infinite circle of death and life, the ancient Mesoamericans understood their world. The priests of Xipe Totec skinned enemy warriors and dressed in their skins as an offering to the generous god who had given food to their ancestors. The bloody side of the skin faced out, and the hands, still connected by strings of flesh, hung loosely from the priests’ wrists.

In homes and temples, Xipe Totec was represented by clay figures. A being that rose out of the scales of old skin. When the old skin sloughs off, a new being is born. And he is born into suffering.

With the arrival of the Spanish, the priests of a strange new god banned these practices. Human sacrifice was prohibited and nearly all native holidays were replaced by Christian ones. But people always combined some aspects of both faiths. In the case of El Salvador, instead of paying homage to Xipe Totec, people started worshipping the Holy Cross. Every May 3, instead of a priest donning human skin, wooden crosses are set out and hung with fruit in thanks for the rain and the renovation of the earth and its plenty.

But the Indians, in a wink to their ancestors (and to Xipe Totec) make their crosses with wood from the mulato tree, which constantly sheds its bark, its skin. And so every May 3, as El Salvador prays to the Christian cross and venerates the sacrifice of the Christian God, at the same time we are venerating another god who also offered his skin to save our ancestors.

Xipe Totec, Our Lord the Flayed.