9

Mission Hollywood 1:

A Cleanup in the Clique

Marbelly has learned an amazing hominoid skill: putting one foot in front of the other to move forward. She practices walking constantly, and, at two years old, grabbing at anything she can and is nearly always at the point of tumbling into the dirt. Like any father, Miguel Ángel has taken precautions. A curious child in this home, however, runs risks different from those she would face in most homes around the world.

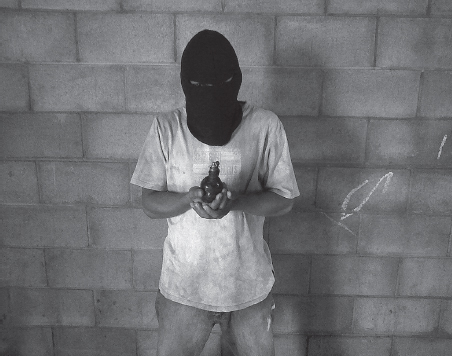

Miguel Ángel has a grenade. Not a homemade bomb. Not a Molotov cocktail. An M-67 industrial grenade—the type that the soldiers and guerrillas would hurl at each other in the mountains during the twelve years of civil war. To Miguel Ángel, it’s a kind of life insurance, although it’s really more like death insurance. Aware that Marbelly wants to explore every nook of their home, her father has put his grenade on top of a high beam so that she won’t one day find it, pull its rusty pin, and blow them all to pieces.

“This piece is a little sensitive. If I pull the pin and let it drop, the balloon pops … It pops and I’m a goner, but I’ll take whoever’s around with me,” Miguel Ángel says as he pulls out the pin and, after a moment, secures it back into place.

His life has always been so close to the edge of the abyss that trusting in a little rusty ball of metal doesn’t seem out of the ordinary. Not to him or to Lorena.

Sometimes it’s worth pausing a moment. There are details—but are they just details?—that powerfully capture complex realities in just a few words. Miguel Ángel and his family, knowing that the Mara Salvatrucha wants them dead, sleep next to a grenade. Miguel Ángel understands death, and he prefers, for his and his family’s sake, that they die by grenade rather than by the Mara Salvatrucha.

He’s gotten skinnier. You could see his ribs before, but now it’s worse. The basket of provisions the Salvadoran state sends him is just enough to eat frugally for a week. Detective Pineda sometimes—sometimes—supplements the basket with a few dollars from his own pocket. The rest of their income comes from selling the marijuana Miguel Ángel grows outside their shack, or from asking for “donations” from Coke or Pepsi delivery drivers. They shell out reluctantly. When an ex-gangster, even if he’s retired, asks for money in the street, it’ll always have a whiff of extortion.

Lorena serves up a plate of boiled chayote flavored with lime and salt. Marbelly shows off her newfound talent and toddles toward her parents. She takes a piece of chayote and sticks it in her mouth. It’s hot, but she eats it anyway, giggling.

Miguel Ángel takes a piece and swallows it. He’s sitting on a half-buried tire in the yard in front of the shack. His past comes to him in waves. As it turned out, he explains, he hadn’t yet proved enough that he wanted to become a soldier of death. Shortly after killing for the Beast for the first time, she asked for more. This time she wanted the blood of a friend.

Miguel Ángel kept an M-67 grenade hidden above a ceiling beam, intending to use it on himself and his family if they were cornered.

“What happened was that the barrio forced me to fuck up this loco from the Gauchos who didn’t want to join up with the Mara. He was my homeboy, but a Gaucho, not a Hollywood. Because the loco didn’t want to follow MS-13’s rules,” he says, sitting on the tire.

No Place for the Timid

The majority of new gang members didn’t need—and still don’t need—to be forced or threatened in order to join. Poverty in Central America pushed them right into the gang’s arms. The general hardship, lack of opportunity, violence, and quasi-medieval living conditions, turned joining up with MS-13 into a completely logical choice. It’s a choice between being nobody and being part of something. Between being a victim or a victimizer. Being Miguel Ángel Tobar or the Clown of Hollywood. In those years, however, just before the turn of the millennium, Chepe Furia couldn’t wait around for poverty to do its convincing. Barrio 18 was arming itself. A war was looming.

With the clique already established, mostly by former members of neighborhood gangs, Chepe Furia needed to make clear to the kids already jumped in, as well as to future members, that joining the Mara is not always an option. For the kids who belonged to rock-throwing, chicken-stealing gangs, there was only one path that didn’t lead to MS-13.

“So they threw us a line. The thugs who didn’t want to accept the two letters, that didn’t want to be part of the big MS-13 family … you got to drop them flat. Bam! They finished El Pollo. Cut his throat. You couldn’t defend anybody in those days, because they’d just say, ‘Hey, are you with the Mara or not? Are you blue or not?’” [Translator’s note: Blue has multiple connotations in this context—it refers to the traditional color of Southern California gangs, the blue of the Salvadoran flag, as well as the blue of tattoo ink.]

It brought home to them how things were changing, how nothing would be the same again.

And the strategy was effective. Nobody messed with the Mara Salvatrucha 13. It wasn’t a group you could join for a while, have some fun with, and then leave. It came and it took over. MS-13 doesn’t nibble, it devours. And the boys understood, they got it, but they also understood that the Mara is a competitive space, where everyone’s after prestige and honor, status and perks. Everything was permitted, even eliminating rivals for the most trivial infractions, so that everyone was as blue as you. It was a time for building character, preparing for what was to come.

Those who didn’t get the message were done for. A kid confused about the complex gang argot accidentally called himself “bicha,” which is most commonly used to refer to members of Barrio 18. “Done for,” Miguel Ángel remembers. Another kid, an aspiring gangster blazed on marijuana, committed a similar error: he referred to himself as a female. Instead of saying he was pedo (high), he used the feminine form of the adjective, peda. “Done for.” Wiped out. Young kids who were just developing into teenagers as they became members of the Mara Salvatrucha were settling their differences by machete. The toughest of them survived. Chepe Furia was letting them weed themselves out, purifying the ranks. And he had a name for the purification. He called it Mission Hollywood (though he would also use this name for a massacre that would prove fundamental in the gang’s history and formation).

Only the most brutal survived: those ready to kill for the pure fun of it, or to obey an order. Those fateful mistakes and confusions, committed by youngsters who often didn’t even know how to write, were so trivial that Miguel Ángel has practically forgotten them—even though, back when he was the Hollywood Clown, he was in the thick of the drama. Because it wasn’t important, because nobody was waiting for those kids to come home, because they lived in destroyer homes in the San Antonio neighborhood and ended up rotting on the banks of the river. Maybe that’s why he barely remembers the details. So many murders were still to come, so many gruesome, sadistic deaths, that maybe these early deaths were buried in his memory beneath the avalanche.

Everything moved quickly. The Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha de Atiquizaya was growing. The police started following their trail. And the nascent clique was beginning to get into skirmishes with their Barrio 18 enemies.

In neighborhoods like Chalchuapita, Centro de Chalchuapa, La Periquera, and others around Atiquizaya, Chepe Furia’s cousin, Moncho Garrapata, had started to organize other kids on the street, under a different banner: Barrio 18.

In the last years of the 1990s, these two men, who both came of age during the Civil War, founded a kind of cultural movement based on the most disturbing values. They steered the young toward a dark abyss. An extremely violent whirlpool in which these young sought respect and status. In order to stop being nobodies and become feared men, they made a deal with the Beast: I’ll give you Miguel Ángel Tobar and you give me the Hollywood Clown of the Locos Salvatrucha.

With both sides armed and ready, it was time for the game to begin.