12

The Hollywood Soldier

Mission Hollywood had left the Clown and his clique exhausted. The Eighteens of Chalchuapa knew how to shoot back, and many MS members died during the war. Both gangs’ territory became more and more defined. Atiquizaya was mostly MS-13. Chalchuapa was mostly Barrio 18. That division continues today.

The police of Ahuachapán, backed by the local forces of El Refugio, Turín, Chalchuapa and Atiquizaya, launched an operation to capture gang members.

The Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha weren’t only losing members to death, but also to jail.

By 2000, the gangs weren’t yet plainly at the center of El Salvador’s national security debate. Newspaper headlines mostly reported armed assaults and kidnappings of upper-class children.

El Salvador was violent. In 2000, it was, if we apply United Nations standards, epidemically violent. At the turn of the century this small country had a rate of 45.5 homicides for every 100,000 inhabitants. Pretty bad. And yet, the five-year period between 2000 and 2005 would be El Salvador’s most peaceful period in the twenty-first century so far.

Peace in El Salvador is another country’s extreme violence.

The police were hardly investigating the cliques, their leaders, or their members. They weren’t even documenting any piecemeal investigations they were conducting. In 2008, Detective Pineda had to start from scratch because his colleagues hadn’t kept any data. Instead, they’d gone out like hunters, looking for the easiest prey. The average age of a clique member was about eighteen, and many were already getting face tattoos. The police’s plan was to scare everyone and hunt down whoever let their guard down. The cases they had against gang members were weak. Accusations of assault, homicide, attempted homicide, battery—all without much in the way of evidence or witnesses. Proof of the police’s incapacity to properly deal with the gang problem lies in the fact that many of the most infamous gang members of the moment would land back in the streets just a few years later. Officers hoped they could stem the tide by decommissioning some of the young warriors for as long as possible, which wasn’t very long.

X, the child gang member dazzled by the recent deportees who danced to Tavares in 1993, was successively detained in several jails around that time, just as Mission Hollywood was coming to an end. X was first locked up in July 1999, and not released until a decade later. Right around then the government decided to imprison members exclusively by affiliation, in secluded prison wings (or “gang universities”). This practice marked the rise of the national MS leadership behind bars.

If the bloody war between lost boys marked the gang’s infancy, its young adulthood was marked by the imprisonment of homies and recent deportees.

X recalls that the gangs didn’t yet control the jails in 2000. In fact, he himself would shake his cell bars begging to be let out of La Esperanza (better known as Mariona or Miami). X knew that La Raza ruled the prison, and that he was in the minority. The prison guards had to hit X’s fingers with a club to get him inside his cell. X remembers one guard’s parting words: “We lock you up at night so we won’t have to find your body in the morning.”

X was sent to cell 27, ward 2. He was greeted with a question and a slap with a machete. “And you, injun, what’s up with you?” barked a member of La Raza before hitting him with the flat face of his machete. “Look what happens to troublemakers,” and he lifted a sheet hung as a curtain.

“Two were giving it to El Spider de Apopa. One forcing Spider to suck him off and the other banging him from behind. Spider was eighteen years old,” remembered X in June 2017, a grimace darkening his face in the small interview room of an immigration detention center in Texas. He was waiting for a judge to review his petition under the United Nations Convention against Torture. Given the blood he shed in El Salvador—and hounded as he was by the Salvadoran police—X isn’t eligible for asylum, but he can try to avail himself of the convention. To do so, however, he must show that if he is repatriated there’s a greater than 50 percent chance that he’ll be tortured. If his judge only knew what El Salvador is like. If his judge only knew what it means to desert the MS-13. If his judge only knew the long history of the gangs. If his judge only knew that if X stepped one foot in El Salvador, the MS-13, the Barrio 18, and the police would know. And they’d all want to get a hold of him.

X says El Spider died of AIDS, years later. He remembers the prisons eliciting only two things in a gang member: anger and fear.

The next morning X was attacked by a group of inmates and taken to a place within the prison known as El Pepeto. When they arrived, five Emes, of the Mexican prison gang, were lined up like children in trouble, surrounded by members of La Raza. They were being interrogated by an infamous prisoner known as Macarrón, right-hand man of Bruno, the Raza leader. X was lined up next to El Panther, El Fool, El Pirate, El Dragon, and El Shaggy, and then clubbed in the chest, the back of the legs, and the back. They ordered him to lift a dumbbell with powdered-milk cans, filled with cement, hanging off either side. The circle of men with machetes was closing in. X understood that if he bent down to lift the weights he’d be attacked, so he jumped up onto the tabletop and ran. The other five Emes followed, trying to escape La Raza’s machetes. They reached the cell bars X had rattled in desperation the day before, begging the guards to let them out. Most of the guards only laughed. But one, named Carballo, opened the door and the Emes were able to escape what would have been yet another massacre in the Salvadoran prison system. The chase yielded two machete wounds, one on Pirate’s hand and the other in X’s abdomen, where he still bears a scar.

As has happened again and again throughout the history of these gangs, a space that was supposed to rehabilitate them, offer them an alternative, only pushed them into further violence. The gangsters jailed in Salvadoran prisons in the twenty-first century confronted the same questions as the migrants who’d reached California in the 1980s: What are you capable of doing to save your life? Can you fight? Are you willing to kill? Will you be the hunter or the hunted?

The six MS-13 gang members, still shaking with fear, were taken to the Island, the cell for targeted inmates. There were three other Emes there: Spuky de Viroleños, Cuchumbo de Novena, and El Diablito of Hollywood, who, currently, and at least since 2008, is the most celebrated MS member in El Salvador as well as the face of La Ranfla, the gang’s national leadership, formed by incarcerated members in 2002. Through collective decision making, La Ranfla has established many of the general norms that Salvadoran gangs abide by. If we were to conduct a survey asking who is the leader of the MS-13, most people would answer El Diablito. He’d already done several stints in prison, having been repeatedly taken out of one and locked up in another to save his life. He was sentenced to thirty years for premeditated homicide in July 1998. And yet, despite being in prison, he would be tried a further six times for conspiracy, threats, illegal possession of war weapons, and homicide.

El Diablito, unlike Chepe Furia, joined the Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha after having only spent fifteen years on the streets of Los Angeles. In the early ’90s a man named Sandoval jumped him in and gave him the gang name Diablón (Big Devil), though in the Salvadoran prisons where he’d remain until 2017 he was known as Viejo Bigotudo (Old Mustaches) or Sam Bigotes. Diablito, real name Borromeo Henríquez Solórzano, came back from the United States as a teenager. He was welcomed by a gang legend, Ozzy de Coronado. Following Ozzy’s lead, he refused to recreate the Californian cliques in El Salvador, founding new ones instead: Harrison Locos, Sanzíbar Locos, Criminal Mafiosos, Big Crazys and Guanacos Criminal. That’s to say, Diablito did not create Hollywood Locos in El Savador. It was Chepe Furia, despite having been a member of the Fulton in Los Angeles, who created Hollywood Locos.

This would have its consequences for Chepe Furia, but not until much later.

Back in 2000, X found Diablito in the isolation cell, scared, covered in bruises, and with a broken hand. El Diablito is now one of ten Salvadoran MS members on the US Treasury blacklist, but back then, alone and angry in his cell, he was part of a generation of gang members itching to enact their revenge against the “civilians.” They’d arrived at a place where they were not victimizers but victims. And they didn’t like that role. The gang members who were jailed in those years, like all who were arrested in the west after Mission Hollywood, would die, serve life sentences, or emerge from jail after having earned a ton of street cred.

Those in prison—around 8,000 people in 2000—were going to taste the gangs’ wrath. The system, until then exclusively controlled by the civilian mafias, was about to get a makeover. The prison massacres would continue through the decade.

The Hollywood Locos who remained outside of prison were part of a clique that was drastically starved of members by 2000. Only five were left, including the Clown. Chepe Furia had disappeared once again, and the Clown was sure that their leader was hiding in Guatemala.

Only sixteen years old, the Clown had already come full circle. Born into war, recruited into the MS-13 by an ex-military officer, he decided it was now his time to hide. The Clown presented himself at a military barracks and asked to sign up.

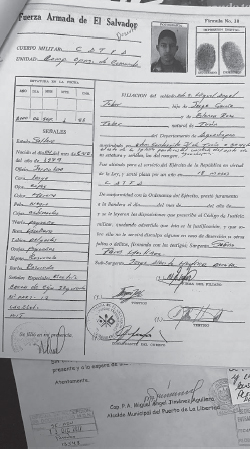

Record no. 38 of the Transmission Support Command of the Armed Services of El Salvador states: “On the sixth day of September 2000, before the witnesses, Sergeant Sabino Flores Martínez and Deputy Sergeant Jorge Alberto Martínez Bonilla, Miguel Ángel Tobar, of Salvadoran nationality, son of Jorge García and Blanca Rosa Tobar, measuring 5 feet 2 inches, with previous employment as a day laborer, brown eyes, dark skin, and a scar on his left eyebrow, and without any legal documentation, enlisted under oath.”

That day, he pledged to the flag of El Salvador after being read to from the Military Justice Code, warning of the impossibility of pardon in cases of desertion and other offenses or crimes. Below, between the signatures of the two military officers, are the poorly written letters, M and A, and two fingerprints attesting to the Clown’s decision to join the army.

On the same page is the Clown’s photo. His head is shaved and, though the image is in black and white, thanks to the style and the patches you can tell he’s wearing the classic olive-green uniform. A son of war clad in war garb. The look on the Clown’s face reminds us of Detective Pineda’s theory about the gaze kids have before and after they kill for the first time. This isn’t the gaze of a child. It’s the gaze of a broken man. It’s the impassive, severe, stony gaze of someone who’s seen too much. Who has seen, and done, terrible things. At the time the photograph was taken, the Clown was already a seasoned murderer.

One word appears next to the Clown’s face: deserter.

That word would weigh heavily on Miguel Ángel Tobar’s life.

Miguel Ángel was born on January 4, 1984, according to the ID card he would acquire years after joining the military. When he presented himself at the barracks, he was barely sixteen. He had no military experience, but he did have four years of experience as a member of MS-13.

In those days you didn’t have to take a polygraph test to rule out gang membership. State security forces didn’t yet fear being infected by what was still a relatively obscure virus. The minister of defense in 2017, David Munguía Payés, acknowledges that “minors were often accepted in the military back then. People would bring in their misbehaved kids and beg us to take them off their hands, as a favor.” And this despite laws banning recruits under eighteen.

The Clown received his military training at the Transmission Support Command in San Salvador. The Salvadoran state first trained the Clown in basic soldiering skills: marching, the use of military-grade weaponry, military regulations, and how to handle and maintain radio communications equipment. During his first three months in service, the Clown, funded by Salvadoran tax dollars, perfected his use of the M-16 rifle, the M-60 machine gun, and M-67 grenades.

Miguel Ángel signed up for the army aged only sixteen, too young to enlist legally. Written to the left of the photo is the word “deserter.’’

And Miguel Ángel, who only thought of the military as a safe place to hide, started to scavenge. Every two weeks he’d take whatever M-16 ammo fit into the left pocket of his olive-green uniform. He’d trade the ammo with other cliques around the country for ammo that was useful to the MS, or he’d sell it off to criminals. Into his right pocket he’d sometimes slip an M-67 grenade, like the one that years later would keep his family safe at night. Once, after seeing how poorly the military warehouses were guarded, the Clown stole three grenades in one weekend. He was disappointed to find, once he got to Las Pozas, that he’d mistakenly taken three smoke grenades. More successfully, Miguel Ángel stole dozens of bullets that would later carry death throughout western El Salvador.

There’s a major pipeline between military arsenals, gangs, and drug traffickers. Between 2010 and 2017, the public prosecutor’s office prosecuted more than two dozen military personnel for stealing grenades, rifles, and machine guns. The M-60 machine guns, which can fire up to 550 bullets per minute, have been sold on an MS-13 clique for $3,000 each.

When the Clown went on leave, he was visited by the four members of the Hollywood Locos who’d been left stranded in El Refugio and Atiquizaya. Sometimes Ángeles Locos members came around, and, less often, members of the Parvis Locos. “So many fucked-up little bichas,” the Clown would think to himself. The Hollywood Locos still had the G3 rifle that Chepe Furia had given them as a seed weapon, as well as a .357-caliber gun and some 12mm rifles. The Clown took care to keep track of all the weapons in his clique’s possession. But, as time went on, the clique’s cohesion eroded, and the new recruits no longer came to meet him. The Clown felt he was seeing the death of Chepe Furia’s creation.

After receiving seventeen checks from the military and spending almost eighteen months as a grunt by day and a gang member by night, pledging to the flag while contributing to extra-official violence and crime, the Clown deserted. It was a military offense that could land him six months in prison. On February 28, 2002, the Clown stopped presenting himself at the military barracks and slunk back to the rank and file of what had always been his true regiment: the Mara Salvatrucha 13.