The roads from Albany in the summer of 1754 led many places, but by the following spring the principal ones all belonged to the British major general Edward Braddock. “Few generals perhaps,” a contemporary historian would soon opine, “have been so severely censured for any defeat, as General Braddock for this.”1 While occasionally referred to as the battle of the Monongahela, “this” has been far more frequently called “Braddock’s defeat.” Indeed, not until the golden-haired Custer failed to emerge from the Little Bighorn more than a century later would another leader’s defeat be so personalized.

But the rough-cut road that led Edward Braddock to the Monongahela in the summer of 1755 was just one of four in a grand scheme that he was charged with overseeing to secure the expanding borders of King George’s North American colonies. History has long debated whether he was up to the task.

In part, this debate has persisted because there is relatively little to say about Edward Braddock until he disembarked at Hampton Roads, Virginia, on February 20, 1755, and got his first look at North America. He was short in stature, of ample girth, and, at age sixty, by any standard of the time an old man who should have been content to sit by the fireside and glory in tales of his regiment. He was in fact the son of another Major General Edward Braddock, who had commanded the fabled regiment of the Coldstream Guards in Flanders and Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession. Young Edward joined his father’s regiment in 1710 and slowly but surely worked his way up through the ranks, earning his promotions by longevity and loyal service rather than by purchase as was frequently the custom.

By 1745, the younger Braddock was lieutenant colonel of the Coldstream Guards, and he led the regiment in action on the continent the following year. It was in this service that he gained favor with the duke of Cumberland, who was George II’s younger son and the commander of the British army. Much better known for zealous military action than diplomacy, Cumberland had just returned from brutally smashing the last gasp of the Stuart dynasty at Culloden Moor in the Scottish highlands. Braddock was subsequently named colonel of the Fourteenth Foot Regiment, and he joined it at Gibraltar in 1753. Within a year he was promoted to major general and as such was readily available a few months later when Cumberland wanted to impose a military solution on the disarray of Great Britain’s North American frontier.2

In the summer of 1754 that disarray was being felt as abject panic in the offices of Virginia’s lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie, in Williamsburg. News had come from the Ohio country that George Washington’s second military mission to the forks of the Ohio had ended in humiliating defeat. The irony of the date would not become clear for almost a quarter of a century, but on July 4, 1754, Washington surrendered the crude stockade of Fort Necessity, about fifty miles south of the forks, to French forces and humbly retreated eastward to the Potomac. It had taken five years since Céloron’s less than auspicious journey, but the French were now decidedly in control of the Ohio country, and even the Iroquois hastily sent emissaries to mend relations with them.

Dinwiddie reported this calamity to the Board of Trade and other high-ranking officials, but even before receiving Dinwiddie’s official version, the de facto prime minister Thomas Pelham-Holles, the duke of Newcastle, warned that “all North America will be lost” unless the English countered French claims. Having said that, however, Newcastle favored conducting a neat and tidy, limited operation that would quickly and quietly secure key points on the English frontier before the French could send reinforcements and escalate matters into a full-scale war. That Newcastle leaned heavily on the less than tactful Cumberland to supply the military muscle for the operation was necessary, if somewhat ill-advised. Cumberland turned to Edward Braddock, perhaps—as some have suggested—because Braddock at sixty still desperately needed a job, but also no doubt because Braddock, too, was not one to allow tact to interfere with results.3

Whatever his strengths and weaknesses, General Braddock arrived in America with sweeping orders. Newcastle’s neat and tidy approach had developed with Cumberland’s involvement into a grand offensive scheme. Absent a formal declaration of war, Great Britain would nonetheless simultaneously attack the French frontier at four points. Given the communication and transportation networks of the time, “simultaneously” was, of course, a relative term.

Two regiments newly raised in the colonies and named after the heroes of Louisbourg in the previous war—Shirley and Pepperell—were to march west along the Mohawk River and seize Fort Niagara. Other colonials from New England, New York, and New Jersey were to strike north up the Hudson and rid the English of the annoying French finger of Fort Saint Frédéric at Crown Point. Still other New Englanders were to attack French outposts in Acadia and perhaps even seize the prize of Louisbourg that the English had given up once before. The fourth column, comprising two regiments of British regulars augmented by colonials and led by General Braddock himself, was to follow Washington’s footsteps back to the forks of the Ohio and evict the French from the newly built Fort Duquesne.

As noted above, there was no declaration of war, and so the British claimed—apparently with straight faces—that these movements were simply designed to expel the French from lands that legitimately belonged to England. This had some degree of truth based on the Treaty of Utrecht in the case of Acadia and even Fort Duquesne, La Salle’s grand claim of the drainage of the Mississippi notwithstanding; but it didn’t stand up very well with regard to the other two locations. The French, after all, had occupied Fort Niagara for seventy years and Fort Saint Frédéric for twenty-four.4

Both sides, it seems, were not yet thinking globally. Each naively thought that it could fight a limited war restricted geographically to North America. The duke of Newcastle—hardly the shrewdest person ever to govern England—sensed a lack of popular support for any war an ocean away when his countrymen had had their fill of countless others just across the channel. “Ignorant people,” the duke noted—apparently not counting himself in that characterization—“say what is the Ohio to us, what expense is there likely to be about it, shall we bring on a war for the sake of a river.”

The French were equally wary of an all-out war. As Braddock arrived in Virginia, French commanders in the Ohio Valley received word that “His Majesty [Louis XV] is on his side very far from allowing that any invasion be undertaken against his neighbors” and that any operations should be “strictly on the defensive.”5

But it wasn’t going to happen that way. Talk of limited war while the troops engaged were mostly colonial militia was one thing, but the distinction became quite muddy when both British and French regulars were committed to the field. Indeed, the fiction of Newcastle’s neat, tidy, limited war was disproved before the transports bearing Braddock’s two regiments disappeared from the Irish coast.

Even with the slowness of communications, there were really no secrets in this age. Spies told the French crown of the sailing; and in response Louis XV—despite whatever peaceful notions he might profess to the contrary—ordered some 3,000 of the best-trained French regulars on the continent to sail for Canada. Under the command of Jean-Armand, baron de Dieskau, these troops were to reinforce Quebec and Louisbourg and stand ready to counter any British advance.

Just as the French knew of Braddock’s departure for America, so, too, did the British know about the sailing of these French reinforcements. Nearsighted Newcastle determined to stop the French convoy not in European waters—that might prove too great a provocation—but in American waters, where the remoteness from Europe might lessen the import of the act even if it made finding the French fleet decidedly more problematic. Accordingly, Newcastle dispatched Vice Admiral Edward Boscawen with eleven ships of the line and two frigates to cruise off Louisbourg and “fall upon any French ships of war that shall be attempting to land troops in Nova Scotia or go … through the Saint Lawrence to Quebec.”6

In any encounter on water the odds were that France would almost certainly be weaker. In fact, the French merchant fleet was in such dismal condition that the troops and munitions for these regiments were crowded onto ships of the line instead of transports. Normally carrying sixty-four to seventy-four guns, these battleships were faster than transports, but in order to accommodate the troops, as many as two-thirds of their cannon had to be removed. Therefore, if Boscawen’s fleet could catch the French, it would face them with overwhelming firepower.

So, the race was on. The French hoped to sail by mid-April 1755, but hampered by adverse winds, they did not depart Brest until May 3. The fleet was under the command of Rear Admiral Dubois de la Motte, who flew his flag from the seventy-four-gun ship of the line Entreprenant, one of only three men-of-war in the fourteen-ship French convoy that had not been stripped down to accommodate troops. Admiral Boscawen had already sailed from Plymouth on April 27, and hoped to be waiting for the French somewhere amid the cold fog of the Grand Banks.

The fog could be friend or foe. De la Motte’s fleet arrived off Newfoundland without incident but despite countless signals quickly became hopelessly scattered in the fog banks. Then on June 6, with only three other French ships close at hand, de la Motte’s Entreprenant caught sight of the bulk of Boscawen’s fleet. Wisely, the French ships slipped back into the murky gloom to avoid it. Three other French ships were not so lucky. The Alcide, Lys, and Dauphin Royal were off the southern coast of Newfoundland west of Cape Race when Boscawen’s lookouts caught sight of them and the admiral gave chase.

The sixty-gun Dunkirk led the pursuit followed by Boscawen’s flagship, Torbay, and two other ships of the line. Captain Toussaint Hocquart of the sixty-four-gun Alcide, one of the French ships with its armament intact, lay back to cover the flight of the Lys and Dauphin Royal to the northwest. The former was laden with eight companies of regulars and the latter with nine. As the British ships closed on the Alcide with gun ports open, Captain Hocquart was determined not to be the aggressor. If this was Newcastle’s limited war, so be it, but France would not be the one to start it. As the Dunkirk bore down on the Alcide, Hocquart called out in English, “Are we at peace or at war?” When there was no answer, Hocquart hailed a second and third time with the same query, “Are we at peace or at war?”

Finally, the Dunkirk’s captain, Richard Howe, replied in French, “La paix, la paix”—“At peace, at peace.” Scarcely had the words died away when the Dunkirk’s cannon belched a broadside at close range. Whether Howe was duplicitous, or Hocquart merely a dupe—there was a red pennant flying from Boscawen’s flagship that signaled “attack”—is debatable, but the result was not. Dunkirk’s broadside was double-shotted with both cannonballs and grapeshot and chain, and the result was havoc. Hocquart and his crew fought bravely if briefly and soon struck Alcide’s colors.

Other British ships closed with Lys. Armed with only twenty-four of the lighter cannon of its normal complement of sixty-four, Lys ran with a gentle breeze for a time, but was eventually overtaken after a daylong chase. Its captain, too, was forced to surrender or be cut to pieces. Only the third member of the trio, Dauphin Royal, which happened to be one of the fastest ships in the French navy, escaped to the safety of the harbor at Louisbourg.

Boscawen was ready to declare a victory, but others were not so sure. One by one, or by twos and threes, the remaining French ships made their way into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and up the river to Quebec. There was no denying that New France had been reinforced. The loss of the Alcide and Lys aside, de la Motte had managed to deliver seventy-eight companies of regulars, some 2,600 troops, to the gates of Quebec with the loss of only ten companies and two ships.7

“In America, the disputes are,” Newcastle had postulated a few months before, “and there they shall remain for us; and there the war may be kept.”8 But in the wake of Admiral Boscawen’s actions that was no longer the case. Lord Chancellor Philip Hardwicke, who had participated in the deliberations over sending Boscawen in the first place, put his finger squarely on the problem. “What we have done,” Hardwicke wrote to Newcastle, “is either too little or too much. The disappointment gives me great concern.”9 Wherever Edward Braddock’s roads led, he was now certain to find forewarned commanders and fresh faces to greet him.

Edward Braddock—the soldier used to giving orders—arrived in Virginia and proceeded to do just that, managing in the process to alienate almost everyone he encountered. Braddock immediately went to Williamsburg to confer with Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie and then summoned governors De Lancey of New York, Shirley of Massachusetts, Morris of Pennsylvania, and Sharpe of Maryland to meet with them at Alexandria. Rather than ask the governors’ cooperation and assistance, Braddock demanded, indeed expected, it. That attitude didn’t go over very well with anyone.

“We have a general,” wrote William Shirley’s son, also named William, “most judiciously chosen for being disqualified for the service he is employed in almost every respect.” Assigned to General Braddock as his secretary, the younger Shirley would have cause to feel Braddock’s inadequacy all too personally within a few weeks.10

Braddock reciprocated this animosity. Having assumed too much the role of the conquering Roman consul, he confessed, “I cannot say as yet they [colonials] have shown the regard … that might have been expected.” But that hardly kept him from being upset with New York and Massachusetts for continuing to trade with French Canada, indignant at Quaker Pennsylvania for showing little enthusiasm for the entire military effort, and decidedly opposed to Governor Shirley’s plan to combine efforts and jointly strike Fort Niagara first. That way, Shirley reasoned, Fort Duquesne would wither on the vine like an unharvested grape. Absolutely not, replied Braddock. The duke of Cumberland’s orders dictated that the first attack be against Duquesne, and against Duquesne it would be.11

Fort Duquesne was certainly not the Gibraltar of the west, but in less than a year’s time the French had turned it into a reasonably defensible position and proved young Major Washington’s assessment of its strategic location. Under the command of Captain Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecoeur, workers quickly tore down the Ohio Company’s hastily begun stockade and in its place erected a solid structure approximately 150 feet square—compact, to be sure, but easily the most imposing fortification on the Ohio frontier. That it should be named for the recent governor general of New France was further proof that the French intended it to be a powerful and permanent fixture.

Squeezed into the very point of the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela, the fort had two sides protected by the merging rivers and the other two sides protected by a maze of ditches and embankments. The ramparts facing the land were built of squared logs and backfilled with earth up to ten feet thick. On the watersides, upright round logs formed a stockade wall twelve feet high. Four bastions anchored the corners of the enclosure and were topped with an assortment of two- to three-pound swivel guns and six-pound cannons. The main entrance was on the eastern side via a gate and drawbridge, and there was a postern or back gate on the riverside.

Inside the stockade was a minuscule parade ground barely half the size of a tennis court that was surrounded by a guardhouse, the commander’s quarters, the officers’ apartments, the enlisted men’s barracks, and a storeroom. A kitchen, blacksmith shop, powder storeroom, and prison were housed under the four bastions. The forest was cleared for a distance of about a quarter of a mile—more than a musket shot—and the stumps were chopped off at ground level. Corn was planted in this area, where there was also a collection of bark huts and cabins built to house the remaining troops.12

General Braddock was quite aware of all this. In fact, he was privy to a very accurate map of the entire French post. His source of information came from Major Robert Stobo, one of two English hostages George Washington had accorded the French after his surrender of Fort Necessity. Sent to Fort Duquesne as leverage to ensure the release of French prisoners captured by the British, Stobo promptly went to work sketching the fortifications and then had his drawings smuggled out of Fort Duquesne by a Delaware Indian.

How much this information may have influenced Braddock on his advance is debatable, but Stobo’s sketches of stout ramparts and open approaches may have convinced the general that he was in for a classic siege. In any event, Braddock insisted on dragging with him an artillery train that included monstrous eight-inch howitzers and twelve-pounders taken from a Royal Navy vessel. “I have my own fears,” wrote the British admiral from whose ships Braddock procured them, “that the heavy guns must be left on this side of the hill.”13

Braddock’s army of some 2,000 regulars, provincials, and a few sailors assigned to the artillery finally marched out of Fort Cumberland, Maryland, on June 10, 1755—much later than the general had planned. Truth be told, it was lucky to get off at all. Supplies in general and wagons and horses in particular had been painfully difficult to obtain, and only the prompt intervention of none other than Benjamin Franklin had managed to save the day.

Franklin initially contacted Braddock in his role as deputy postmaster general, seeking to facilitate communications among the far-flung prongs of the general’s military operations. Quick study that he was, Franklin immediately recognized the muddle with supplies and went to work, going so far as to hint in a newspaper in Pennsylvania that if horses weren’t made available for purchase, Braddock might be forced to confiscate some.

Within a couple of weeks, 150 head of horses and wagons loaded with provisions funded in part by the Pennsylvania General Assembly stood ready at Fort Cumberland. Whatever his opinion of colonials, Braddock was deeply grateful for Franklin’s prompt leadership in securing Pennsylvania’s assistance and acknowledged to Franklin that Virginia and Maryland “had promised everything and performed nothing,” while Pennsylvania “had promised nothing and performed everything.”14

But if at last well provisioned, Braddock’s army was nonetheless a lumbering ox when finally under way. Heavy wagons, cumbersome artillery pieces more suited for coastal bombardment than frontier operations, and a string of camp followers all blunted rather than sharpened its strategic focus. Essentially following Washington’s route of both 1753 and 1754—which was, of course, really the route of Christopher Gist and his fellow traders—the column took seven days to travel twenty-two miles. It looked as if the journey to the forks of the Ohio was going to be very slow.

Braddock realized this on the evening of June 16 and chose to divide his command. He would push on with approximately 1,300 men, the bulk of the artillery, and about a quarter of the wagons. Reports of increased French reinforcements at the forks were almost as ubiquitous as the trees that were being felled to permit the passage of his wagons, but whatever truth they held suggested that speed was essential. In hindsight, however, all that this division of command accomplished was to weaken a plodding beast, not speed two-thirds to its destination.

Braddock’s advance force still had to cut a road through dense forest and over rolling hills, and it even stopped to bridge streams. Another twenty-two days passed before the column arrived on the east bank of the Monongahela some eight miles southeast of Fort Duquesne. Along the way Braddock repeatedly refused the entreaties of several subordinates that he order up the remainder of his command.

Now, on the evening of July 8, 1755, there was another decision to be made. The route that day had taken the column through a narrow valley lined with steep hills where the column was ripe for an ambush. Braddock’s precautions had been textbook perfect: secure the hilltops and mouth of the valley before the main column moved through it. All this had been done without incident, but the route ahead on the east bank of the Monongahela offered a similar passage—dense narrows tightly confined between the river and the high bluffs that spilled onto the ford at Turtle Creek. It was another likely spot for an ambush and this time, on the advice of his guides, Braddock elected to avoid it completely.

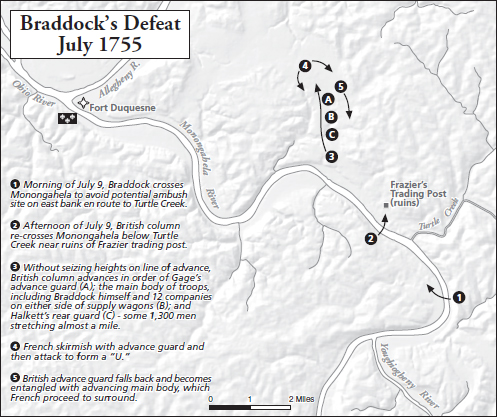

Consequently, on the morning of July 9, the column forded the low waters of the Monongahela to its western bank and proceeded northward through more favorable terrain. It then recrossed the river to arrive back on its eastern bank below Turtle Creek, near the ruins of John Fraser’s most recent trading post. (Poor Fraser seems to have been in the thick of things no matter where he hung his hat!)

The order of march for Braddock’s column that afternoon—by all accounts a sunny day—was similar to what it had been all along. The Indian agent and trader George Croghan and seven Indian scouts led an advance guard of some 300 regulars under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage. These troops included grenadiers of the Forty-fourth Foot and a company normally commanded by young Captain Horatio Gates, but this day under the leadership of Captain Robert Cholmley with Gates at his side. Behind the advance guard came engineers, axmen, and road builders under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Sir John St. Clair, followed by a long line of wagons loaded with supplies and tools. More troops formed a rear guard to this lead division that “was drawn out over a distance of about one-third of a mile.”15

About 100 yards to its rear came the main body of troops, headed by a detachment of light horse and another body of workmen, including the British sailors detached to Braddock’s service along with the heavy cannon. Next came the general’s guard and Braddock himself, accompanied by his two aides-de-camp, George Washington and Robert Orme. Washington was quite ill, suffering from dysentery and hemorrhoids so painful that he “could ride a horse only by tying cushions over the saddle,” and he had caught up to Braddock’s advance command only the evening before. His absence appears to have been necessitated by his abysmal physical condition, but one wonders if he remembered that the terms of his parole from the French at Fort Necessity the previous year dictated that he not return to the Ohio country for at least a year.

The main force of regulars followed the general and was divided into twelve companies, half on either side of another long line of wagons that carried the bulk of the force’s supplies. Finally, there was the rear guard of the entire force, commanded by Sir Peter Halket and including a company of colonial rangers from Virginia led by Adam Stephen, who about thirty years later would passionately persuade Virginia to ratify the Constitution. In all, it was a column of about 1,300 men—reports vary as to the exact number—that stretched almost a mile from Fraser’s abandoned post northward into the woods.16

Key ingredients clearly missing from this force, however, were Indian allies. The southern Catawba and Cherokee, who might have been inclined to help, remained out of the campaign largely because of a rivalry between South Carolinia’s governor James Glen and Virginia’s lieutenant governor Dinwiddie. Glen had originally suggested a military conference of southern governors and then championed just the sort of strategy session that Braddock called in Alexandria. But Dinwiddie ignored the first and then blocked Glen’s invitation to the latter on petty grounds motivated by political jealousy. Miffed, Glen saw to it that his Catawba and Cherokee allies stayed in the Carolinas.

There wasn’t any help from the Iroquois either. At first, the Iroquois were annoyed that the campaign might include their traditional southern enemies, the Catawba and Cherokee. By the time they learned that it wouldn’t, those Iroquois who weren’t still smarting over the purchases of the Susquehannah Company were equally disgusted with infighting among the British over whether they should join William Shirley’s effort against Niagara or William Johnson’s against Saint Frédéric. Whatever else they were doing, the Iroquois weren’t setting forth for the Monongahela.

Finally, Braddock had held negotiations with groups of Ohio Indians, principally Delaware and Shawnee. The general’s bluntness about the purpose of his mission was hardly constructive even to a temporary alliance. Most certainly, Braddock told the assembled chiefs, this was to be the great war for empire—British empire, not the return of Indian lands from the French. By the time Braddock concluded his oration, these potential allies, too, were offended and quickly melted away into the Pennsylvania woods. That left only seven or eight—depending on whose count one believes—Mingo to scout for Braddock’s caravan.17

Meanwhile, the French commandant at Fort Duquesne, Captain Pécaudy de Contrecoeur, was not hampered by lack of Indian support. It was, however, the Potawatomi and Ottawa of the western Ohio country, who came to the forks to fight for the fleur-delis. According to the historian Francis Jennings, they did so more to curry favor with the French in those western lands than through any great notion of restoring Indian sovereignty east of the Ohio. No matter what their motives, Pécaudy de Contrecoeur would have been in deep trouble without them. By the time the commandant ordered Captain Liénard de Beaujeu, his newly arrived replacement, to lead the bulk of French forces up the Monongahela and intercept Braddock, they numbered 36 French officers, 72 French regulars, 146 Canadian militia, and 637 Indians—roughly two-thirds Braddock’s number.18

In historical shorthand, the battle that followed is frequently called an ambush. Actually, the initial encounter may have taken both sides by surprise. Beaujeu and his advance units suddenly appeared in front of Gage’s lead ranks. Far from being a dense thicket, the forest north of Fraser’s cabin was actually fairly open, evidence of an Indian hunting ground that had been cleared of underbrush by burning. The French began to spread out, and Gage’s troops fired one or perhaps two musket volleys. At 200 yards, the results were minimal, but among those who fell dead was Captain Beaujeu. Rather than panic, his second in command, Lieutenant Jean-Daniel Dumas, quickly steadied the French regulars across Gage’s front, while his Indian allies advanced largely on their own accord to form a U around both sides of the British column. Gage’s advance guard retreated and fell back on the first company of wagons and road workers.

For some reason, Gage had failed to send troops to take control of a hill to the right of his line of march, as he had done in similar terrain just the day before. The attacking French and Indians soon occupied this high ground and began to pour a deadly fire into the British column strung out below. Under pressure, Gage’s advance guard continued retreating in column, telescoping inward on itself in the process and quickly intermingling the various units into a disorganized mass.

On hearing the sounds of this action, General Braddock’s textbook response should have been to order his main body to stand firm until the extent of Gage’s engagement could be ascertained. Inexplicably, Braddock instead ordered his main force to advance in column. The result was that the two key pieces of Braddock’s command—Gage’s advance force retreating down the road and the main body of troops advancing up it—collided in even greater confusion.

The French and Indians continued to fire into this entangled mass of redcoats, who nonetheless stood their ground despite the confusion in their ranks. Braddock and his aides-de-camp, Washington and Orme, were in the thick of things, rallying the troops and directing courageous if somewhat ineffective volley fire into the woods on three sides. Gage’s retreat had abandoned two six-pound cannons, and the French now turned them against the head of the British column and added their fire to that coming from the surrounding woods.

By most accounts—and there are many—this situation continued for at least two hours. Then, bullets finally found General Braddock, who had already had five horses shot from beneath him. Braddock fell severely wounded; and as Washington and others moved him toward the rear, the resolve of the British regulars, who—contemporary criticism to the contrary notwithstanding—had valiantly stood their ground, disappeared. Their next maneuver, along with the remainder of Braddock’s command, was a headlong rush for the ford at the Monongahela. “When we endeavored to rally them,” Washington later wrote, “it was with as much success as if we had attempted to stop the wild bears of the mountains.”19

So, the flight eastward continued. Four days later, within a mile or so of the ruins of Washington’s Fort Necessity, Major General Edward Braddock succumbed to his wounds. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the middle of the rough road, and the surviving wagons and troops of his command passed over it to obscure its location. Most of the other dead were not so lucky.

Upwards of 500 men from Braddock’s command had died. Five years later, their bleached bones would still be visible to a passerby, spread “so thick that one lies on top of another for about a half mile in length, and about one hundred yards in breadth.” Among the dead was William Shirley, Jr., shot through the head at the side of the general he despised. Almost as many had been wounded. Some of them would die before reaching Fort Cumberland. By one report, the French losses were twenty-eight killed and about the same number wounded, while the Indian losses were eleven killed and twenty-nine wounded. There was little doubt that Newcastle’s plan to secure the British frontier had met with a stunning defeat.20

Braddock’s defeat is one of those battles that have been fought and refought a thousandfold. In the aftermath of the American Revolution, it was popular to describe Braddock’s loss as the defeat of Old World tactics—the opening volley in a contest that ultimately saw the British system unsuited to the demands of America’s expansive frontier. But later historians have argued that this interpretation overlooks the fact that the Old World order did not function on the banks of the Monongahela even as it should have functioned in the Old World.

On at least three counts, Braddock’s actions that day were counter to Bland’s Treatise of Military Discipline, the military bible then in use on European battlefields. First, the general had rushed his main body forward into confusion rather than forming up and standing firm to await the report of his advance guard. Second, he had not marched his command by smaller platoon units that could have more readily turned the long column into offensive lines. Finally, Gage had failed to take possession of the high ground above the line of march. And why had Braddock divided his force in the first place? With 2,000 troops arrayed before them, the French might have faced such overwhelming numbers that they would have abandoned Fort Duquesne on their own.21

Disastrous as Braddock’s defeat was, however, it was to have graver ramifications well beyond the banks of the Monongahela. Among the many wagons and tons of supplies and munitions captured by the French that day was the general’s trunk, complete with the war plans of the other three roads of attack, as well as Major Stobo’s drawings of Fort Duquesne. This latter evidence proved an embarrassment to Major Stobo, rendering him more a spy than a gentleman prisoner, but the other campaign plans sparked both military maneuvering and political indignation. The French found not only detailed plans for the attacks against Fort Niagara and Fort Saint Frédéric, but also extensive plans to surprise New France and “invade it at a time when, on the faith of the most respectable treaties of peace, it should be safe from any insult.”22 When these documents reached Paris, they were a diplomatic bombshell. So much for Newcastle’s limited war.

And what of those other roads that Edward Braddock had contemplated for the summer of 1755? From Albany, Major General William Shirley, who after Braddock’s death became commander in chief of British forces in North America, finally marched and paddled 200 miles to Oswego on Lake Ontario, arriving there on August 17, still 150 miles short of Fort Niagara, his goal. As the dog days of late summer took their toll on his men, Shirley received reports of a growing concentration of French troops at Fort Frontenac across Lake Ontario and decided to fortify Oswego and remain there instead. Another of Braddock’s roads had been stopped short of its objective.

Albany also saw the departure that summer of Major General William Johnson’s force of about 2,000 provincials determined to expel the French from Fort Saint Frédéric. Johnson had a shorter distance to go than Shirley; but just when his advance was moving forward, he stopped to build Fort Edward at the portage between the Hudson River and the southern end of Lake George. He did so, Johnson explained, because “in case they were repulsed (which God forbid) it may serve as a place of retreat.”23

Meanwhile, Dieskau, having escaped the clutches of Boscawen’s fleet, had planned to sail against Shirley at Oswego, but Braddock’s captured letters convinced him that he should parry the threat toward Lake Champlain first. “Make all haste,” Canada’s governor general Vaudreuil urged him, “for when you return we shall send you to Oswego to execute our first design.”24

Even without Braddock’s captured papers, however, the French and Canadians had already been moving south from Fort Saint Frédéric and begun building Fort Carillon at a place the British called Ticonderoga. On September 8, 1755, Dieskau sailed south up Lake George from Carillon. (Lake George drains north into Lake Champlain, which in turn drains north into the Richelieu River and eventually the Saint Lawrence. Thus, sailing south on both lakes is going up the waterway.) Hoping to surprise the British, French regulars along with Canadians and Indian allies crept through the forest and poured volley after volley into Johnson’s camp. When the British finally counterattacked, Dieskau was wounded and captured.

Each side claimed victory, but might just as easily have claimed a stalemate. The French continued construction of their fortress of Carillon at the southern end of Lake Champlain. Johnson proceeded to build a second fort, William Henry, at the southern end of Lake George. For the British, this road, too, was a dead end.

Finally, there was Acadia. Perhaps because this prong of Braddock’s four-part plan had gotten an earlier start, only here did the British meet with some success. On May 26, 1755, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton sailed from Boston with 2,000 provincials and 280 regulars to attack Fort Beauséjour on the isthmus joining Nova Scotia to New Brunswick. The fort was manned by several companies of French regulars and nearly 1,000 Acadian militia, but when British artillery hauled from Halifax began a bombardment, it was “enough to bring about the surrender of the fort because fire combined with inexperience made everyone in that place give up.” Nearby Fort Gaspereau was also captured, effectively cutting the land route between Quebec and Fortress Louisbourg. Capturing Louisbourg would require greater efforts, but in the meantime, the British busied themselves with deporting more than 6,000 Acadians, most to faraway Louisiana, to prevent them from aiding the French cause in either Quebec or Louisbourg.25

Notwithstanding Nova Scotia, Braddock’s roads in the summer of 1755 had led nowhere, but an interesting chain of subsequent encounters flowed from that day on the banks of the Monongahela and involved three of Braddock’s principal lieutenants: George Washington, Thomas Gage, and Horatio Gates. All three earned their spurs of leadership that day, but they would have cause to stand on different sides twenty years hence. By 1774, Thomas Gage was the royal governor of Massachusetts, charged with overseeing a veritable hornet’s nest of colonial unrest. His heavy-handed administration only made things worse, and after militia fired on his troops at Lexington, the fat was in the fire. Gage ordered the attack on Bunker Hill and soon found his army besieged by the newly minted Continental Army under the command, of course, of George Washington.

Washington’s adjutant general was Horatio Gates, who had gone home to England after the French and Indian War and only recently—with Washington’s encouragement—returned to America to settle on land in western Virginia. Within the first two chaotic years of the Revolutionary War, Gates quickly became a major general—again with Washington’s blessing—and after the all too common political infighting found himself in command of the American army at Saratoga. The subsequent surrender to him there of General John Burgoyne’s British army was arguably of even greater significance than Yorktown. The latter was the finale; but without the decisive victory at Saratoga, the fuse of revolution might have been snuffed out.

By then, Thomas Gage had departed Boston for England and become the scapegoat of the deteriorating colonial situation generally, and of the British defeat at Bunker Hill specifically. One of those who chastised him was a fellow officer who wrote that Gage was “an officer totally unfitted for this command.”26 That critic was John Burgoyne, who soon would know the ultimate meaning of “scapegoat.”

Horatio Gates emerged from Saratoga a hero, but willingly or not soon found himself involved with the “Conway cabal” that questioned Washington’s leadership. He was once more at his plantation in Virginia when Congress summoned him to save the Carolinas after the fall of Charleston in 1780, Washington at the time being occupied containing another British army in New York. Gates chose his ground wisely and hoped for another Saratoga, but when most of his militia fled the field, the battle of Camden became one of the most disastrous American defeats of the war. How different, then, were the roads that led from the Monongahela that day in 1755 for Thomas Gage, George Washington, and Horatio Gates.