If Braddock’s roads did not lead to a strengthening of Great Britain’s North American frontier, they did lead to the one place where the duke of Newcastle had not wished to go—all-out war with France. The full-blown conflict was made inevitable not by the frontier struggles in North America, but by a diplomatic upheaval among the powers of Europe. England and France were on opposite sides—there was no question about that—but between 1754 and 1756, the European alliances of the previous war shifted dramatically.

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria started the political shuffle by steadfastly refusing to accept Frederick the Great’s accession of Silesia in 1740. Great Britain, Maria Theresa’s chief ally in the War of the Austrian Succession, had not proved aggressive enough for her purposes, so the empress went shopping for a new European friend. She found one in her old foe, France, now under the influence of Louis XV’s mistress, the marquise de Pompadour.

Once the two women got to plotting, Austria’s recapture of Silesia was to be but the first step in dividing up all of Frederick’s territory. Empress Elizabeth of Russia, daughter of Peter the Great, eyed Frederick’s East Prussia and soon made it a trio against Frederick by allying Russia with Austria and France. Faced with this new alliance, which might well make France the supreme power on the continent, the duke of Newcastle’s government had little recourse but to align itself with its old enemy, the enigmatic Frederick.

The remaining European force, which might have tipped the balance of power,* was Spain. Although the days of its glory, before the Armada, were long past, Spain was nevertheless still a key player and the holder of major stakes in the New World. But despite the Bourbon blood of the royal houses in both Spain and France, Ferdinand VI resolutely proclaimed Spain’s neutrality. In doing so, he was taking to heart his country’s interests much more than the dictate of the Treaty of Utrecht that Spain and France never become one. Much to the chagrin of Louis XV, who relentlessly lobbied for his cousin’s involvement, Ferdinand shrewdly recognized that Spain had more to lose than to gain in the conflict. It was a lesson that Ferdinand’s successor would have done well to remember a few years later.

So, with new partners, both England and France prepared for global war. Still smarting over Braddock’s defeat, Newcastle’s England was in no great shape and desperately needed time to build up its forces. France, too, which might have declared war immediately after England’s attacks in North America in 1755, was all too happy to have some time to prepare, particularly in building up its navy. Samuel Eliot Morison asserted retrospectively that after the Treaty of Utrecht England was the sea power. Three decades after that treaty, however, even England still did not believe it. Lord Anson, soon to hold the Royal Navy’s highest post, first lord of the Admiralty, wrote in 1744, “I have never seen or heard … that one of our ships, alone and singly opposed to one of the enemy’s of equal force has taken her…, and yet we are daily boasting of the prowess of our fleet.”1

But England did have a numerical advantage. In the spring of 1756, according to one estimate of comparative naval strength, England had more than 160 capital ships, including about 100 ships of the line, each armed with 50 to 100 cannons, and more than 60 frigates, each with 32 to 40 cannons. Against this, the French could float only 60 ships of the line and 31 frigates. The number in each class actually fit for service varied greatly with individual reports. But the French were rushing the completion of at least 15 more capital ships either by purchase or in their own yards. Newcastle looked at these figures and feared that should the Spanish Bourbons change their minds, a combined French-Spanish armada would have “decided numerical superiority.”2

But France was not looking for an epic naval battle in the English Channel. Rather, it hoped to build on the success of de la Motte in eluding Boscawen the previous year. This effort had suggested that France could use its smaller but speedier navy to reinforce North America and its other outposts around the world while keeping England on the lookout for offensive operations closer to home. Eager to adopt these tactics even before a declaration of war, the French minister of the marine, Jean-Baptiste Machault, dispatched three squadrons to North America in the spring of 1756: two to the Caribbean and a third to Canada with another round of reinforcements. Meanwhile, France used its overwhelming strength in land forces to threaten the possibility of an invasion across the Channel.

In England, Newcastle was roundly criticized for fretting about the danger of such an invasion from France. But even though no such attack had occurred since 1066, it was still a possibility—enough, in fact, for King George II to confide that “neither the service of America, neither the defense of Minorca nor any project whatever would incline us to dégarnir [strip] our coasts by sending out too many ships of war.” Frederick the Great, too, warned the British minister in Berlin of French plans for an invasion. He may well have exaggerated them to solidify his own new alliance with England, but nonetheless, his warning was passed on to Newcastle with the assertion that “we could not be too much on our guard.”3

So, with Great Britain thus preoccupied, France decided to make a quick grab for British territory, just as General Braddock had tried to do against French interests the previous year. France looked for a weak spot and found it in the Mediterranean island of Minorca. Thirty miles wide and fifteen miles in diameter, this eastern point in the Balearic Islands off the coast of Spain had a long history of diverse colonization stretching from the Greeks to the Moors. The British had captured it from Spain in 1708, and their ownership was confirmed by the Treaty of Utrecht. Now an important naval base for both trading and military purposes, Minorca was arguably second only to Gibraltar in importance to Great Britain’s power in the Mediterranean.

As stealthily as possible, then, the French massed 15,000 men and a train of siege artillery under the duc de Richelieu and sailed out of Toulon aboard 170 vessels on April 10, 1756. Naturally, British spies reported the preparations and Newcastle fretted some more over the fleet’s destination. Was it Minorca, Gibraltar, or…? Against the 2,800-man British garrison at Fort Saint Philip on Minorca, this force was excessive, but turned loose elsewhere, perhaps even on the banks of the Thames, it would be of a size to cause utter chaos. Sailing with this convoy were twelve ships of the line commanded by the marquis de la Galissonière, the same man who as governor of New France had dispatched Céloron down the Ohio.

Given Britain’s concern over safeguarding the English Channel, its Mediterranean squadron was down to four ships of the line, three frigates, and one lone sloop. Thus it fell to England’s second-ranking naval officer, Vice Admiral John Byng, to sail from Portsmouth with a hastily assembled fleet to counter the threat. Byng, a lifelong sailor, was fifty-two and was the son of a storied admiral. He had never been very popular with his crews, perhaps because he was rather austere and a strict disciplinarian. Nonetheless, he had a long career of solid if undistinguished service in the Royal Navy.

By the time Byng’s fleet, including his ninety-gun flagship, Ramillies, arrived at Gibraltar on May 2, 1756, and joined up with what was left of the Mediterranean squadron, the French forces had landed on Minorca and bottled up its garrison in Fort Saint Philip. It fell to Byng, still operating without a declaration of war, to relieve the siege.

Immediately, there was confusion between Byng’s orders and those of the governor of Gibraltar over how many troops should be provided to Byng’s fleet. This put Byng in a quandary. He could insist on the troops and sail to relieve the garrison at Fort Saint Philip, but what if Gibraltar was invaded in the interim? Or he could sail with the number of troops he already had, hope to defeat the French at sea, and trust that the garrison could hold out until a larger landing force arrived. Either way, Byng faced potential criticism: fail to save Minorca and be censured; lose Gibraltar and be damned.

Byng chose to hope for a naval victory and sailed from Gibraltar with ten ships of the line and three frigates. Off Minorca, Galissonière was ready for him with what may have been one of the finest naval squadrons ever assembled by France—twelve ships of line that were well built, well armed, well manned, and well trained. In fact, the French flagship, Foudroyant, was one of the superweapons of the day, not only mounting eighty-four guns but also including a battery of fifty-two-pounders, clearly capable of throwing more broadside weight than any rival.

Byng attempted to communicate with the beleaguered Saint Philip garrison on Minorca, but on May 20, the sails of the French fleet on the horizon intervened. Having already faced one dilemma at Gibraltar, Byng now faced another. Should he engage a fleet that appeared superior in almost every category, or head for Toulon or other points to draw Galissonière away from Minorca? Galissonière’s position was far simpler, and his orders were clear-cut: defend the French beachhead on Minorca and prohibit the reinforcement of its garrison. Byng chose to attack.

Securing the weather gauge, Byng planned to run his fleet in a line obliquely toward the French ships and then tack and turn in line in the opposite direction, continuing to run obliquely at the enemy as the fleets sailed past each other. Properly executed, the plan would have been for British broadsides to pummel the sterns of the French ships, which would have had difficulty turning into the wind to engage their own full broadsides.

It was a good plan, calculated to wreak as much havoc as possible and then permit the fleet to escape intact—ready for the next round. But as the British fleet came about and moved closer to the French ships, the captain of the Defiance, now leading Byng’s van, misunderstood the signal to sail obliquely and instead led his division straight into the French line. This had the effect of putting British ships’ bows on to French broadsides. Byng was furious; and by the time the fleets were disengaged, half of his ships were heavily damaged and no longer fit for action. Byng withdrew, while Galissonière continued his defense of Minorca.

Now what? Byng faced the decision of remaining near Minorca and attempting to land troops despite the French fleet or returning to Gibraltar. After counsel with his officers, it was their unanimous opinion that the fleet should retire to Gibraltar. It was, of course, their opinion but Byng’s ultimate responsibility, especially after Fort Saint Philip surrendered a month later.

In a year that held no good news for Newcastle’s government from any front, Admiral Byng was subsequently court-martialed, found guilty of numerous counts of misconduct, and sentenced to death by firing squad aboard the Monarch in Portsmouth harbor. It was a sentence passed in the heated emotions—both public and governmental—of a year of defeat, and it was not exactly the high point of the Royal Navy.

In retrospect, Byng’s concern for Gibraltar and his decision not to risk his entire fleet when other corners of the British Empire were far more dependent on it than Minorca, may well prove his competence. And, of course, if his orders had been carried out competently in the first place, the result may have been far different. Instead, his execution became one of the most egregious affairs in the annals of the Royal Navy. The French philosopher Voltaire, who would pen more than his share of wry comments on the ensuing war, summed the matter up thus: “In this country [England] it is a good thing to kill an admiral from time to time to encourage the others.”4

Upon learning of the invasion of Minorca, Great Britain declared war on France on May 18, 1756. France reciprocated on June 9. Frederick the Great—without bothering to inform his British ally of his plans—put another log on the blaze by invading neutral Saxony a few months later. The British in North America would come to call the conflict the French and Indian War and trace its beginnings from Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity in 1754. In Europe, where peace and war tended to blur even in the best of times, it would after the fact be called the Seven Years’ War. Later still, Samuel Eliot Morison looked at its global scope and the enormous geography at stake and remarked, “This should really have been called the First World War.”5

Europe itself, North America, and the Mediterranean—where else would the rivals collide? High on the list was India. With the decline of the Mogul Empire in the early 1700s, the subcontinent of India had reverted to a polyglot of largely autonomous provinces under varying degrees of foreign influence. The rich Indian trade that the Portuguese had pioneered before Columbus had long been contested by other European powers, particularly around Bombay on the west coast, Calcutta in the northeast, and Madras on the southeast or Coromandel Coast.

During the War of the Austrian Succession, French forces from their fortress at Pondicherry (in French, Pondichéry) captured the British trading center at Madras and held it until the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. The British responded by building Fort Saint David just south of Pondicherry. In the uneasy peace that followed, the French governor, Joseph-François Dupleix, determined that the French East India Company should use troops left over from the war to acquire territory outright, rather than merely paying local rulers for trading privileges. The English East India Company, assisted by Robert Clive, responded in kind, and the result was that between 1751 and 1754 the two trading companies conducted a limited war all along the Coromandel Coast. England and France were still officially at peace, but—as in the Ohio country during this period—that fact did not stop their respective commercial interests and a handful of regulars on the fringes of their empires from engaging in a struggle to push those limits. The world was becoming smaller.

Dupleix was recalled to France in 1754, and both sides in India momentarily paused to catch their breath. Then, before news of the declarations of war reached India, the new ruler of Bengal, who may have feared the same territorial acquisitions that were taking place around Madras, attacked the British settlement of Calcutta. The British garrison there was sorely understaffed, and the fort’s defenses were in a dismal state of neglect. Some Englishmen escaped by ship, but others who surrendered were stuffed into a dungeon that came to be called the “black hole” of Calcutta. Many died of suffocation. France was not directly involved in the infamous affair, but when reports of the “black hole” reached England, it became another sore point for Newcastle’s administration and further evidence of global war.6

And then came more grave news from North America. It had been a rough year in the wake of Braddock’s defeat. Colonel Thomas Dunbar had set the tone early by writing Governor Robert Hunter Morris of Pennsylvania in July 1755 that he intended to retreat from Fort Cumberland with the remainder of Braddock’s command and go into winter quarters in Philadelphia. Winter quarters in July! Morris saw red, and so, too, did the Pennsylvania frontier. It was left wide open to marauding companies of French and Indians. One settler reported from the Susquehanna country, “Sure I am, if there is not some speedy measures taken by men of weight, that we shall be utterly ruined.” And “in short,” the Pennsylvania Gazette noted in an editorial, “the distress and confusion our people in general are in on the frontiers is inexpressible.”7

The situation was no better up north in New York. The Boston Gazette had expressed surprise when William Shirley’s expedition of 1755 halted at Oswego. “We flattered ourselves,” the newspaper noted, “that the three regiments with him, together with the Indians and Rangers, were more than sufficient to have carried both Frontenac and Niagara.”8 By the following summer, however, even Oswego appeared to be out on a limb.

To be sure, Shirley had not forgotten about the two regiments of some 1,500 troops that he had left to quarter Oswego. But after the appointment of John Campbell, the earl of Loudoun, as commander in chief in North America early in 1756, Shirley had less and less to say about them. Before Loudoun arrived in New York, Shirley dispatched Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet and a force of about 500 men from Albany to deliver much-needed supplies to Oswego. This Bradstreet accomplished, but on his return journey, French and Indians ambushed his column. Bradstreet held his own, but the attack and his subsequent report of poor conditions at Oswego should have convinced both Shirley and Loudoun that a major relief effort was needed immediately. Unfortunately for the defenders at Oswego, the urgency of the matter fell victim to the change of command between Shirley and Loudoun and frustrating delays of military bureaucracy.

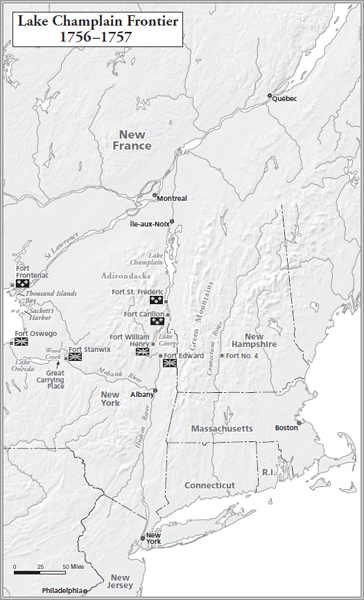

But while the British debated strategy in the aftermath of Loudoun’s arrival, the French were on the move in force. Under the command of the marquis de Montcalm, about whom much more would soon be heard, French forces—numbering about 1,300 regulars, 1,700 militia, and assorted Indian allies—sailed south across Lake Ontario from Fort Frontenac and, at Oswego, surrounded the forts of Ontario, Pepperell, and George. Fort Ontario occupied a rise on the eastern bank of the mouth of the Oswego River. It overlooked Fort Pepperell on the western bank and Fort George, a tiny redoubt farther to the west.

Meanwhile, a British relief force under the command of Colonel Daniel Webb finally departed Albany for the west, but it was to be too late. On August 12, 1756, supported by ships in Lake Ontario, Montcalm opened his attack with a bombardment of Fort Ontario by siege artillery. Oswego’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel James F. Mercer, ordered an evacuation of Fort Ontario the next day, but about all that did was to permit Montcalm to place French cannon on the heights and concentrate his fire on the two remaining fortifications. One of the men who fell under this renewed bombardment was Mercer himself, struck dead by a cannonball that beheaded him. His surviving officers held a council of war and decided to surrender.

“I am master of the three forts of Chouegen [Oswego] which I demolish,” Montcalm reported, and “of 1,600 prisoners, five flags, one hundred guns, three military chests, victuals for two years, six armed sloops, two hundred bateaux and an astonishing booty made by our Canadians and Indians.” Many of the prisoners were shipped to Montreal, but upwards of 100 were massacred in the wake of the surrender before Montcalm could intervene. It should have been a lesson to him for future operations with his Indian allies.9

When the news from Oswego spread, British North America shuddered at this crucial defeat. “Oswego is lost,” bemoaned a New Yorker, “lost perhaps forever.”10 And with it was lost not only the Lake Ontario fleet but, more important, the gateway to the lucrative fur trade that had made Albany so crucial on the northern frontier. Far from plucking French grapes from the vine that tied Quebec to Louisiana, England had just lost all access to Lake Ontario and much of western New York.

The fiery minister of New England Jonathan Edwards wrote to a friend serving as chaplain for a Massachusetts regiment on Lake George and lamented the loss of Minorca and now Oswego. These defeats, Edwards said, would “tend mightily to animate and encourage the French Nation” and make England “contemptible in the eyes of the nations of Europe…. What will become of us, God only knows.”11

The duke of Newcastle wondered the same thing and looked around for help. Who would save England, if only from itself? Who would save England, if only from its own ineptitude? Not everyone in England believed them, but the answers were forth-coming from a forty-eight-year-old member of Parliament, William Pitt. “I know that I can save England,” Pitt vowed, with an assertiveness that had been decidedly lacking in the government, but then also displaying his own enormous ego by quickly adding, “and that no one else can.”12

William Pitt was born in Saint James Parish, London, on November 15, 1708. History would come to call him the “great commoner,” but he was hardly that. His paternal grandfather was Thomas “Diamond” Pitt, a self-made tycoon who had secured the family fortune by trading in India and serving as president of the East India Company and governor of Madras. Diamond Pitt was the original owner of the 410-carat Pitt diamond, dug from the Parteal mines of India and destined to grace the sword of Napoleon. Some said the old man was mad—a claim that would be leveled at his descendants as well—but whether he was truly insane, merely eccentric, or just bullheaded, it was hard to argue with his accomplishments.

“If you ever intend to be great,” “Diamond” Pitt advised his son Robert, “you must be first good, and that will bring with it a lasting greatness, and without it, it will be but a bubble blown away with the least blast.” As to public service, the old man continued, “if you are in Parliament, show yourself on all occasions a good Englishman, and a faithful servant to your country.”13 It was a charge that Robert took seriously when he did in fact serve in Parliament, and Robert’s second son, William, would take it even more seriously.

From these scarcely humble beginnings, William Pitt was dispatched first to Eton and then to Trinity College at Oxford. Ill health—Pitt suffered horribly from gout and other maladies most of his life—kept him from graduating, but he embarked on a self-directed finishing tour on the continent, which included spending time at the University of Utrecht and throughout Holland and France.

Early in 1735, at the age of twenty-seven, Pitt took his seat in Parliament. His journey there had certainly not been that of the average commoner, but he seems to have held a genuine love for liberty and to have realized that it flourished best when the rights of the common man were championed. To the English middle class—still disenfranchised in the mid-eighteenth century—William Pitt became a champion, raising his piercing voice in the House of Commons as their voice. In time, when Pitt spoke, he might not move the government, but the government listened and occasionally trembled nonetheless.

Pitt incurred the wrath of Sir Robert Walpole’s government through his affection for King George II’s eldest but despised son, Prince Frederick, and in turn used his fiery oratory to help bring Walpole down in 1742, in part over criticism of continuing British subsidies to the king’s lands in Hanover. The king, Pitt argued, was turning the nation into “a province to a despicable Electorate [Hanover].”14 There may well have been great truth in that statement, but it was hardly calculated to win Pitt any favor with the king. So, while Pitt held minor positions, including vice treasurer of Ireland, George II steadfastly refused to draw him into his inner circle.

But in 1754, Newcastle’s brother, Henry Pelham, died, leaving a void in the House of Commons. Newcastle himself sat in the House of Lords, and even if he had been inclined toward galvanizing oratory—which he was not—it would have had little impact on the stodgy peerage and even less on the House of Commons. Like it or not, Newcastle looked more and more to Pitt in the House of Commons—out of necessity.

By the fall of 1756, Newcastle’s government was reeling under the triple blows of the losses of Minorca, Calcutta, and Oswego. When Henry Fox, then secretary of state for the Southern Department and Newcastle’s manager in the House of Commons, abruptly resigned, Newcastle asked Pitt for support, but he did not even find sympathy. Pitt brashly announced that he would not serve in any administration that included Newcastle. The duke saw the handwriting on the wall, made a flurry of last-minute political appointments, and resigned on November 11, 1756. A befuddled George II—who, although there were bouts of insanity in his own family tree, was among those to call William Pitt quite mad—nonetheless reluctantly turned to Pitt to form a government. “I am hand and heart for Pitt, at present,” a dejected Newcastle sighed. “He will come as a conqueror. I always dreaded it.”15

But Pitt was not in for an easy ride. Disdaining the treasury, Pitt chose the duke of Devonshire as first lord of the treasury and the nominal head of his government and himself took the position of secretary of state for the Southern Department. The middle class loved him, but their champion had not exactly endeared himself to the House of Commons at large. Many in Parliament opposed him. The duke of Cumberland did not support him. The king, it was said, loathed him. These were not relationships that would inspire Pitt’s confidence or help him to govern decisively. Then, of course, there was still Newcastle. The duke might no longer be the head of the government, but after his nearly four decades in one office or another, the government bureaucracy was filled with his appointees.

Within a month, however, Pitt had boldly written a three-point agenda for George II to deliver to Parliament. First, it recognized the essential importance of the North American colonies to the greater empire. By land and by sea, America must be defended. Second, it created a national militia designed to alleviate fears of a cross-channel invasion, while freeing up regulars for service abroad. Third and last, it called for some measure of relief from the high price of corn and other commodities for the lower class. As with a presidential state of the union address, however, the executive may propose, but how the legislature deposes is an entirely different matter.

It was now up to Pitt to persuade Parliament to craft his ideas into law. He urged that an “expedition of weight” of not less than 8,000 men and a fleet be sent to North America and demanded that the Admiralty provide a list of ships “requisite for the total stagnation and extirpation of the French trade upon the seas.” When he found that 62 of Great Britain’s 200 warships were out of commission, he began a four-year construction program to bring the Royal Navy up to 400 ships of all classes. But he also crossed both king and citizenry over the execution of Admiral Byng. To his credit, Pitt spoke his mind and his conscience. Whatever the circumstances of that day off Minorca, Pitt thought that Byng’s execution was not part and parcel of rectifying them. Against both the crown and popular opinion, Pitt favored clemency.16

That was enough for George II. On April 6, 1757, he demanded Pitt’s resignation and ordered Newcastle to form an interim government. Almost three months of incessant political bickering and intrigue followed. England drifted without a rudder. The disputes were less about policy—all sides agreed that North America must be saved, and even Pitt now saw that subsidies to Hanover and Prussia were central to keeping France busy on the continent—than about personalities. Who was going to stand at the helm? Finally, it became clear that if neither Newcastle nor Pitt could govern England alone, it could not be governed without both of them.

In June 1757, Lord Chesterfield was instrumental in negotiating a coalition government into which Pitt brought the “confidence and support of the people” and Newcastle brought his far better relations with the king, Parliament, and the bureaucracy. Pitt resumed his office of secretary of state. Newcastle assumed his old post as first lord of the Treasury. In effect, Pitt would be prime minister, left to “appoint generals, admirals, and ambassadors” and to carry on the conduct of the war. Newcastle would be what he was best at being—the wizard behind the curtain working the wheels of patronage, currying favor with the House of Lords, and reassuring the king. “I will borrow the duke’s [Newcastle’s] majorities to carry on the government,” the resurrected Pitt told the duke of Devonshire.17

And so a most unusual partnership was born. “The duke of Newcastle and Mr. Pitt,” wrote Lord Chesterfield, “jog on like man and wife, that is, seldom agreeing, often quarreling, but by mutual interest … not parting.” Indeed, their relationship might well be considered the essence of the definition of partnership. Each party needed the other; each brought strengths the other lacked, and each was content—or at least resigned—to let the other do what he did best. “No amount of pressure could create the political machine that was prerequisite for conducting the business of government; the only man with such a machine was Newcastle.” And the only man bold enough to use it was William Pitt.18

“Britain has long been in labor,” Frederick the Great observed later, “and at last she has brought forth a man.”19 It remained to be seen what that man could accomplish. Nevertheless, one fact was now crystal clear. Newcastle had fiddled with it and initially sought to limit its scope, but from now on, there was no doubt but that the conflict in which Great Britain found itself embroiled was Mr. Pitt’s global war.