William Pitt’s gamble in selecting Jeffery Amherst to command the Louisbourg campaign had paid off handsomely. Pitt was to be far less successful in his appointment of a commander to lead the center prong of his grand offensive. Lord Loudoun was out—there was no question about that—but if Pitt had acted precipitately in Loudoun’s removal, as some would later contend, he compounded the error in his selection of a replacement. In truth, Pitt had little choice. George II had gotten his fill of Pitt’s elevating junior officers and insisted that the top jobs of commander in chief in North America and commander of the thrust against Fort Carillon should both go to Loudoun’s deputy, Major General James Abercromby.

Abercromby’s redeeming feature—in George’s eyes at least—appears to have been his longevity. At fifty-two, Abercromby had enjoyed a long, if unremarkable, military career. A Scot by birth, he had served as lieutenant colonel of the Royal Scots, had been a staff officer in Europe throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, had participated in expeditions against France, and in June 1756 arrived in New York as a member of Lord Loudoun’s staff. Like Amherst, Abercromby had never held an independent command, although his preparation for one would at first glance seem to be equal to if not superior to Amherst’s. The problem was that Abercromby was a plodder. Kindly, tactful, never robust in health, he was not one to inspire confidence in his subordinates or to rush into things. Without a doubt, he lacked the fighting spirit, quick wit, and decisiveness of Pitt’s other new commanders.1

Pitt’s orders recalling Loudoun and appointing Abercromby in his place reached New York on March 4, 1758. Among the accompanying dispatches were circulars to the various colonial governors. Loudoun had already asked them to provide “precisely 6,992 provincial soldiers” for the coming campaigns. Now, Pitt demanded that they raise upwards of 20,000. Fortunately, he also gave them important concessions over earlier calls for provincial troops. While he had yet to figure out how to pay for it, Pitt assured the colonial governors that—in the same manner as for British regulars—the crown would supply the required arms, ammunition, tents, and provisions for these new troops. He also declared—although this never came to pass—that he would make strong recommendations to Parliament to reimburse the colonies for their costs of raising, clothing, and paying these recruits. Of value to morale was the added concession that provincial officers as high as the rank of colonel would be accorded parity of rank with their counterparts in the regular army.

The response was astounding. On the morning after Pitt’s letter was read to the Massachusetts assembly, the same legislators who had just refused to accord Lord Loudoun his request for 2,128 men voted unanimously to raise 7,000 on the terms proposed by Pitt. Other assemblies quickly followed suit. Even Connecticut, largely sheltered from the hazards of the front lines by New York and Massachusetts, voted to raise 5,000 troops. Within a month, Pitt’s new policies had resulted in pledges to arm more than 23,000 provincials, plus thousands more to be employed as teamsters, bateaux operators, and craftsmen. Great Britain’s North American colonies had finally been jumpstarted into a major war effort.2

These preparations and the prospect of another year’s campaign soon produced a frenzy of activity and a high state of apprehension all along the New York frontier. Albany should have been used to such anxiety by now, as once again it became the focal point of preparations, but the situation was tense nonetheless. One evening a resident of Albany, whom the newspaper described as “being in liquor,” failed to give the proper answer when challenged by a guard, and the poor inebriate was “fired upon by the sentinel, and killed on the spot.”3

But at least that sentry was trying to do his duty. Some troops from Massachusetts on their way to Albany were camped west of Northhampton when boredom got the better of them. “A number for diversion, cut round the bottom of a large tree with their hatchets,” reported the Boston Gazette. The tree fell on a tent occupied by four or five fellow soldiers. One was killed outright; another had an arm and both legs broken; and the others were badly bruised.4

Given such antics as these, what had the French to fear? First, of course, they had to fear the most penetrating of enemies. British intelligence from Fort Carillon confirmed what had now become the norm throughout Canada: “The French are much distressed for want of provisions, horseflesh runs very high in its price.”5

For his part, Montcalm seems to have vacillated on this subject, one minute wringing his hands and saying that the state of provisions “makes me tremble,” but the next minute, appearing quite unwilling to concede so much as an inch of ground. Despite dire shortages, Montcalm wrote to France in February 1758 that at a minimum any peace settlement should not only restore most of Acadia, but also permanently extinguish British claims to Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, and the Ohio Valley and limit British influence over the Six Nations.6

But what was Montcalm to do, militarily, in 1758 to accomplish this? Governor General Vaudreuil proposed that Montcalm and the majority of French regulars return to the Lake George country and make a powerful feint against Albany. Meanwhile, the chevalier de Lévis with a force of 3,000 handpicked regulars, Canadian provincials, and Indian allies would strike west, first to prevent the British from reestablishing Fort Oswego and then to spread terror down the Mohawk Valley. Vaudreuil hoped—with recent history as a guide—that the British would be paralyzed by the prospect of these two juggernauts and be left in confusion near Albany, not knowing which way to turn. If, in the resulting paralysis, Montcalm should be able to reduce Fort Edward with the same dispatch he had shown at Fort William Henry the year before, so much the better.

But besides the dismal lack of food and other provisions, there was one festering sore in this plan, indeed in the entire conduct of military affairs in New France. The relationship between Vaudreuil and Montcalm was slowly disintegrating. Vaudreuil, it will be remembered, had not taken kindly to Montcalm’s arrival in the first place and each man had claimed the laurels after the French captured Oswego in 1756. At a time when New France required solidarity, “there existed a bitter rivalry, a personal animosity, between its highest executive and its most gifted general that boded no good for the future.” A superior in France counseled Montcalm that now was “not the moment to appraise the qualities and talents of those who direct affairs,” but the growing feud would simmer throughout 1758 before erupting the following year with disastrous results.7

“We are on the eve of the most cruel famine,” wrote a resident of Quebec on May 19, 1758, after the daily ration of flour had been cut in half to two ounces per person. About 1,200 to 1,500 horses had already been purchased to “make up for the want of bread, beef, and other necessaries of life.” Only arrival, in the nick of time, of five flour-laden ships from Bordeaux, which had somehow managed to elude the British fleet, gave the colony some measure of sustenance and permitted the dispatch of troops into the field.8

As spring turned to summer, Montcalm hurried south to reinforce Fort Carillon at the place the Mohawk called Ticonderoga, “the place between the great waters.” A short time later, reports that the British were massing north of Albany in unprecedented strength caused Governor Vaudreuil to send Lévis in support of Montcalm rather than on his western strike. Time would tell whether it was the correct decision.

The British forces were indeed assembling north of Albany in record numbers, but there were many in the cadre of British officers who held a decidedly low opinion of this new influx of provincial recruits. Even after receiving their assistance at Louisbourg, Brigadier James Wolfe was among those voicing the most disdain. “The Americans are in general the dirtiest most contemptible cowardly dogs that you can conceive,” wrote Wolfe. “There is no depending on them in action. They fall down in their own dirt and desert by battalions, officers and all. Such rascals as those are rather an encumbrance than any real strength to an army.”9

There was, however, to be at least one colonial who would elevate himself and a group of like-minded woodsmen to a level of esteem among certain British officers. His name, of course, was Robert Rogers, and he and his rangers would come to be called the original Green Berets of the American army. Curiously, the major histories of this era give little insight into the man. Perhaps it is assumed that Rogers is so well known that the writer need do no more than breathe his name. More likely, these writers, too, have struggled to cut away 250 years of legend and expose the facts.10

Robert Rogers was born in the tiny settlement of Methuen on the northern frontier of Massachusetts Bay Colony on November 18, 1731. His parents were Scots from Northern Ireland who appear to have immigrated to Massachusetts “only a short time before Robert’s birth.” As Presbyterians, they were unwelcome in many New England towns, but the outskirts of Methuen were home to a number of Ulster Scots who had settled there on common ground. It wasn’t long, however, before the promise of individual ownership of new land led his family into the Merrimack River valley of New Hampshire. Here, young Robert would hone his skills as a woodsman and have his first taste of Indian warfare.

In 1745, during King George’s War, the French encouraged Indian attacks all along the New England frontier. Robert Rogers was fourteen that fall and, “by frontier standards, old enough to take his place among men.” By the time the conflict ended four years later, Rogers was a seasoned warrior and, along with a fellow New Hampshire lad named John Stark, eager to be among those to explore farther west into the Connecticut River valley. Such advances by settlers met with renewed resistance from the Indians, particularly by the Abenaki of the village of Saint Francis, and Rogers served in a variety of militia assignments.

Whatever his growing reputation as a “ranger,” Robert Rogers also had his first brush with the dark side that would plague him all of his life. Short on cash and unable to make payments on land he had purchased in Merrimack, he fell under the spell of a counterfeiter named Owen Sullivan. Although not directly engaged in the counterfeiting, Rogers appears to have been among those who knowingly passed false bills obtained from Sullivan. Rogers was arrested along with eighteen other suspects, but never tried. This was in part because the principal culprit, Sullivan, had managed to slip away, but also because now, in the spring of 1755, New Hampshire was suddenly occupied with a far more pressing concern: another war with France. Rogers once more volunteered for duty and promised to recruit a company of men. On April 24, 1755, when the New Hampshire regiment was officially activated, twenty-three-year-old Robert Rogers became captain of “Company One” with John Stark as his lieutenant.11

Numerous assignments followed. Rogers and his men convoyed supply trains north from Albany, scouted French positions along Lake George and Lake Champlain, and captured prisoners needed for interrogations. These assignments were frequently far afield and caused him to miss the two major engagements of those early years: Dieskau’s attack against the British at Lake George in 1755 and Montcalm’s siege of Fort William Henry in 1757—during which Rogers was embarked on Lord Loudoun’s stillborn assault against Louisbourg. But Rogers and his “rangers,” as they came to be called, still saw plenty of action.

In January 1757, Rogers led eighty-five rangers north on ice skates across frozen Lake George and then on snowshoes over the mountains to halfway between forts Saint Frédéric and Carillon. Their mission was to gather intelligence and disrupt the lines of communication and supply between the two posts. The rangers captured several sleighs and seven prisoners, but then learned that two hundred Canadians and forty-five Indians had just arrived at Carillon and were poised to take to the woods and cut off their avenue of retreat.

A fierce fight broke out in the wintry woods. For a time, Rogers and his men appeared to be hopelessly surrounded; and the Canadians, singling out Rogers by name, repeatedly called for his surrender, all the while praising the valor of his men. Although Rogers was wounded in both the head and the wrist, he later reported that he and his men were “neither to be dismayed by their threats, nor flattered by their professions, and determined to conquer, or die with arms in their hands.” That night, under the cover of darkness, the rangers followed one of their cardinal rules of warfare. They broke off their engagement with a superior force, divided into small groups, and melted away into the forest to rendezvous again at a predetermined location.12

Such exploits, while hardly stunning military victories, nonetheless made quite a name for Robert Rogers and his men. In fact, colonial newspapers from this period are filled with reports of their adventures. “We hear that the famous Rogers of Fort William Henry has made another tour near the French encampment at Crown Point [Saint Frédéric],” reported the New York Mercury as early as May 1756. By August 1757, a paper in Boston was calling him “Major Rogers.” A lengthy account by Rogers himself of another scouting expedition against Fort Carillon in force—“the famous Rogers,” he was again called—appeared soon afterward. 13 Had this been the twentieth century, one might have been inclined to look around for his press agent.

But there was always the dark side, too. Occasional defeats in the field were to be expected, but lack of discipline by his rangers and even talk of that ugliest of military words—mutiny—were quite another. During the winter of 1757–1758 considerable friction developed between British regulars stationed at Fort Edward and the rangers of Rogers’s command camped below the fort on Rogers Island in the Hudson River. In November, the rangers’ discipline was less than its best on an unsuccessful raid that Rogers missed because of scurvy. (Shooting at game as one passed and ignoring guard duty were definitely not condoned by the rangers’ rules.) This led General Abercromby to report that if the ranger companies were to be increased as Rogers had requested, “it will be necessary to put some regular officers amongst them to introduce a good deal of subordination.”

The symbol of such subordination that came to grate on the rangers was the six-foot whipping post embedded in the ground on the island. It was “almost the symbol of discipline in the regular army” but was met with great disdain by most colonials. When two rangers were whipped for stealing rum from British stores, word quickly spread that “if rangers were to be flogged, there would not be rangers.” In the fervor that followed—no doubt caused partly by the boredom of a cold winter camp—a group of grumbling rangers surrounded the whipping post and one of them cut it down with a few well-placed blows of an ax.

An uproar ensued on the island and was heard by Fort Edward’s commandant, Colonel William Haviland. Before the matter was put to rest, Rogers stood before Haviland pleading for leniency for those involved and warning of mass desertions if it was not granted. For his part, Haviland proposed that “it would be better they were all gone than have such a riotous sort of people,” but if Rogers would catch anyone who attempted to desert, Haviland would “have him hanged as an example.”

Haviland passed the proceedings of Rogers’s own inquiry into the disturbance on to Abercromby and recommended various court-martial charges “to prevent these mutinous fellows escaping a punishment suitable to their crime.” Meanwhile, Rogers did the only thing he could think of to blunt such criticism: he promptly marched off with 150 men to make yet another raid against the French at Fort Carillon. By the time they returned, the entire sordid affair seems to have blown over, largely because even the staid Abercromby recognized the value of Rogers and his rangers. Whereas most British officers were content to hunker down behind log walls for the winter, Rogers and his men were among the few determined to carry the fight to the enemy no matter what the season.14

Doubtless it came as some surprise, however, that Robert Rogers was to find his greatest champion in the form of an affable and competent English lord. If Pitt was indeed stuck with James Abercromby as his commander in chief in North America, he was absolutely determined that a far more able and assertive field commander be at his side to direct the assault against Fort Carillon. Pitt found that man in George Augustus, viscount Howe, and appointed him to be Abercromby’s deputy.

Lord Howe, born in 1725, was the eldest of three brothers destined to distinguish themselves in Great Britain’s service. He chose the army, and like so many of his generation, saw service in Flanders and elsewhere on the continent under the duke of Cumberland. He embarked for America to serve as Abercromby’s deputy with both a sense of adventure and curiosity.

The second son, Richard, chose the sea and saw duty in both the merchant marine and the Royal Navy before being commissioned a lieutenant in 1745. Assignments of increasing responsibility followed until he was given command of the sixty-gun frigate Dunkirk in January 1755. It was as captain of the Dunkirk that he captured the French frigate Alcide off Cape Race, Newfoundland, the following June. Richard Howe would go on to become a vice admiral and commander in chief of British naval forces in North America during the opening years of the American Revolution.

The third son, William, began service in the duke of Cumberland’s light dragoons in 1746, was appointed major in the Sixtieth Foot Regiment in 1756, and most recently had been engaged under Wolfe at Louisbourg. William Howe’s name would reverberate in North America for the next twenty years, from the heights of Quebec with Wolfe to the forests of the Brandywine against George Washington.

Lord Howe was everything that the stuffy and ineffective Abercromby was not, and British regulars and colonials alike soon came to revere him. “Lord Howe was the idol of the army,” a provincial carpenter wrote, “in him they placed the utmost confidence. From the few days I had to observe his manner of conducting, it was not extravagant to suppose that every soldier in the army had a personal attachment to him. He frequently came among the carpenters, and his manner was so easy and familiar, that you lost all that constraint or diffidence we feel when addressed by our superiors, whose manners are forbidding.”15

Robert Rogers was commissioned “Major of the Rangers in His Majesty’s service, and captain of a company of the same” on April 6, 1758, and ordered to report to Lord Howe at Albany. Rogers did so and “had a long conversation with him upon the different modes of distressing the enemy, and prosecuting the war with vigor.”16 Indeed, Howe was so impressed with Rogers’s tactics that he went on at least one scouting foray with the rangers in order to learn more. Far from indoctrinating the rangers into the regimen of European warfare as Colonel Haviland had recommended, Howe saw to it that the rangers’ style was impressed on the other units of Abercromby’s command.

“You would laugh to see the droll figure we all cut,” read one report from north of Albany in early June; “regulars and provincials are all ordered to cut the brim of their hats off. Even the General himself is allowed to carry no more than a common private’s tent. The regulars as well as provincials have left off their proper regimentals, that is, they have cut their coats so as scarcely to reach their waist:—You would not distinguish us from common plowmen.” No women were allowed to follow the camp, and it was further noted that in the matter of washing clothes, “Lord Howe … has already showed an example, by going himself to the brook, and washing his own linen.”17

Just how completely Lord Howe embraced this wilderness life is best illustrated by an often-told story of a dinner he gave for his officers just before the army embarked on Lake George. Entertaining one’s junior officers in style was an accepted requirement of command in those days, and Howe’s subordinates no doubt arrived at his tent relishing the prospect of a brief respite of English grace and decorum. Instead, they found rough logs in place of chairs and bearskins thrown down on the ground instead of a carpet. There was not a piece of china or silver to be seen. In due course, a servant set a blackened pot of pork and peas on one of the bearskins.

With a knowing glance about him, Howe took a sheath containing a knife and fork from his pocket and began to cut away while his guests looked on in astonishment. “Is it possible, gentlemen,” his lordship asked, “that you have come on this campaign without providing yourselves with what is necessary?” Polite laughter turned to sighs of relief only as Lord Howe moved to distribute a similar knife and fork set to each of them. It was a far cry from what might have been expected in similar circumstances in Europe; but this was not England, and Lord Howe seems to have been the most astute of the British officers in recognizing that difference. For their part, the colonials idolized him for doing so.18

By June 8, 1758, Lord Howe was encamped at Fort Edward with about half of Abercromby’s army. Two weeks later found them at the ruins of Fort William Henry on the southern end of Lake George. Upwards of 500 wagons were at work between Albany and the lake hauling supplies and matériel northward after them. On Lake George itself, more than 1,000 bateaux, “each capable of carrying twenty-five men,” were being readied for the assault down the lake.

Contemporary accounts speak of building boats to “cross the lake,” but to one who has not wandered along Lake George’s forested shores, those words do not paint the full picture. To be sure, the object was to “cross the lake,” but Lake George is one to three miles wide and thirty miles long. What was now required was to row from the ruins of Fort William Henry north down the lake to its northern outlet, which led through a short passage before emptying into Lake Champlain within an easy artillery shot of Fort Carillon.19

Major General Abercromby arrived at the Fort William Henry camp with the remainder of his army on June 28, but it was still very much Lord Howe’s show. Howe sent Rogers north to make a detailed reconnaissance of Fort Carillon and the line of advance, including the best landing site at the lake’s northern end and the approach to the fort. He also ordered Rogers to survey Lake Champlain for three miles beyond Carillon and “discover the enemy’s forces in that quarter.” Howe, it seems, was being quite thorough.20

Reports of the exact numbers of troops engaged in the campaign vary, but most speak of about 15,000—approximately 6,000 British regulars and 9,000 colonials, easily the largest army yet assembled on the North American continent. Thirty-five miles away at Fort Carillon, Montcalm was doing his best to scrape together an opposing force of less than 4,000. “In all human probability,” wrote one correspondent, “a few days will decide the dispute.”21

Early on the morning of July 5, 1758, Abercromby’s army—under Howe’s able command in the field—took to its boats and sailed north down Lake George. What a sight that must have been! The glint of thousands of muskets and the flutter of regimental colors filled the lake as the dull clunking of oars and the staccato beat of drums resounded from the hillsides. By one account some 900 bateaux and 135 whaleboats were laden with men and accompanying baggage, stores, and ammunition. Artillery pieces followed on heavy flatboats. One wounded officer wrote from Albany two weeks later, “I never beheld so delightful a prospect.”22

Down the lake they went, first to Sabbath Day Point, twenty-five miles away, by late afternoon. After briefly resting and allowing the long line of boats to close up, the advance guard started off again just before midnight. It was led by Rogers and Lord Howe in the first boat, but also in the vanguard was a light infantry regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage, the same officer who had led Braddock’s advance across the Monongahela three years before. Designed to be more mobile and more rapidly deployed than regular British regiments, this light infantry regiment was the British army’s way of having regular troops that could imitate the tactics of Rogers’ Rangers without some of the rangers’ antics. It would prove to be the beginning of light infantry units in the British army.23

Dawn found the leading boats passing under the granite slabs of Rogers Rock, which rises above the western bank of the lake near the narrows at its northern end. (Legend subsequently suggested that earlier the same year Rogers had escaped from a pursuing party of French and Indians by sliding down this precipice—on his seat or on snowshoes; take your pick—but Rogers himself fails to mention it in his journal.24) On this July morning, Rogers was no doubt much more concerned about a French advance party of some 350 regulars and Canadian provincials who watched every movement of the British from the heights.

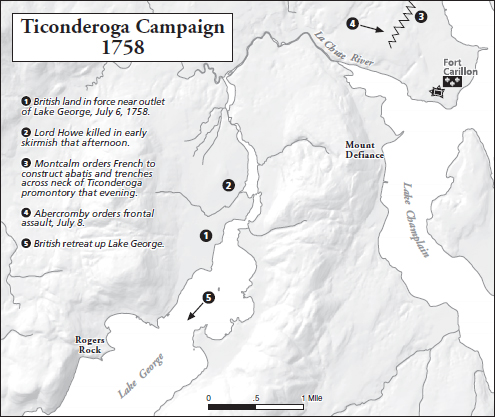

By noon on July 6, the bulk of the British forces were ashore at the northern end of the lake. Hindsight suggests that Howe should have ordered the entire army to follow Rogers along the route he had previously reconnoitered and close with Fort Carillon as quickly as possible. But this was easier said than done. Montcalm had perhaps as many as 1,500 troops spread out along the connecting stream between Lake George and Lake Champlain. There was also the French advance guard, now descending Rogers Rock and trying to make its way back to the main French lines. Finally, there was the forest itself. A dense thicket of timber and undergrowth extending down to the water’s edge gave grim testimony as to why the British had opted to sail the thirty miles down Lake George in the first place.

According to Rogers, it was General Abercromby who directed him to take some rangers and seize high ground about a mile inland from the landing place. This left Lord Howe to advance with other ranger units and elements of Gage’s light infantry. In the tangled woods directions quickly became confused, and any sense of a line of battle disintegrated. What does appear to have happened, however, is that Lord Howe remained on the leading edge of the confusion, gallantly indeed, but this was hardly the place for the man Wolfe later called “the spirit of that army, and the very best officer in the King’s service.”25

Howe’s advance guard collided in the deep woods with elements of the French advance guard rushing north from Rogers Rock to avoid being cut off. “A sharp fire commenced in the rear of Lyman’s [Connecticut] regiment,” Rogers recorded, and when it was over, the French had been routed but Lord Howe was dead, killed almost instantly by a musket ball through his chest. One unsubstantiated report suggested that Howe had been calling for the surrender of a French officer when he was struck, or he simply may have been hit in a hail of blindly fired bullets. The result was the same. “So far things had been properly conducted and with spirit,” wrote Captain Joshua Loring of the Royal Navy, “but no sooner was his lordship dead, than everything took a different turn and finally ended in confusion and disgrace.”26

With the death of Lord Howe, both the inertia and the intelligence of the British advance faltered. The advance guard spent the remainder of the day disentangling itself from the wooded maze and then returned to the landing site to regroup. Abercromby was two hours’ march from Fort Carillon, but he would spend two days getting there. Yes, the woods were dense; yes, there was the prospect of an attack by the French; but rather than strike quickly, Abercromby dallied and constructed an entrenched camp at the site of a French sawmill just two miles from the fort. “I can’t but observe,” recorded a physician from Massachusetts named Caleb Rea, “since Lord Howe’s death business seems a little stagnant.”27

Abercromby’s delay was Montcalm’s good fortune, and Montcalm made the most of it. He had arrived at Carillon only the week before to find a dismal shortage of both men and supplies—by now the modus operandi of all military operations in New France. As the British force passed under Rogers Rock, Montcalm pondered his fate. Where should he make his stand? There was little chance of holding Fort Carillon against a protracted siege. For one thing, he and his men would soon starve to death. If things went poorly, Montcalm stewed, Fort Carillon might turn out to be Fort William Henry in reverse.

Several of Montcalm’s lieutenants favored making a stand at the sawmill and in the woods along the outflow stream from Lake George. Others warned that this location was susceptible to enemy fire from the surrounding heights, parts of which Rogers was indeed soon sent to seize. So, on the evening of July 6, as Abercromby’s army regrouped from the skirmish that had cost it Lord Howe, Montcalm made his decision. He ordered his troops to undertake a flurry of construction across the narrow neck of the Ticonderoga promontory northwest of the fort.

From the fort at the eastern tip of the promontory, the terrain sloped gently westward and then rose to a rounded hill that fell away toward the most likely route of the British advance. Just below the crest of this hill, Montcalm’s men dug shallow entrenchments and then cut huge logs to stack above them. In front of these works for nearly 100 yards, they piled a series of deadly abatis, tree limbs strewn about like a tangled web. Leaving only one battalion to man the artillery in the fort, Montcalm then deployed the majority of his troops, including recent arrivals led by the chevalier de Lévis, along this line. Providence help the enemy that advanced on them.

But truth be told, their present enemy had no compelling reason to advance directly against them. Montcalm prepared for a frontal assault, but left his flanks sadly exposed. To be sure, the terrain there was much more rugged, but overwhelming numbers thrown against either flank might have been enough to turn the outnumbered French line. Or, for that matter, why not simply reduce this formidable barricade with artillery?

To the southwest of Fort Carillon and just over a mile away, the rounded hump of Rattlesnake Hill (later renamed Mount Defiance) rose some 700 feet above the waters of Lake Champlain and the outflow stream from Lake George. Montcalm’s haste and lack of manpower had by necessity left its slopes undefended. Having taken great pains to float an artillery train of sixteen cannons, eleven mortars, thirteen howitzers, and 8,000 rounds of ammunition down Lake George, Abercromby might now have taken what time he needed to array his cannons on Rattlesnake Hill and blast the French out of their entrenchments. But having dithered when he should have charged, Abercromby now charged when he should have waited for his artillery to be dragged into place. Nineteen years later, during the American Revolution, the advancing British recalled the lesson and in a day’s time placed cannons on the slopes of Mount Defiance. The Americans surrendered the fort without firing a shot.

Early on the morning of July 8, Abercromby sent a junior officer forward to make a reconnaissance of the French lines. After only a cursory look, he returned with the assertion that the trenches could be carried by a frontal assault. Abercromby did not ask for a second opinion from the more experienced officers, including Thomas Gage, who with Howe’s death was suddenly second in command. Indeed, the only question that Abercromby asked his staff, before ordering them into an eighteenth-century forerunner of the charge of the Light Brigade, was whether they wished to advance in ranks of three deep or four deep. Three deep was the answer, and while his artillery remained at its landing site, Abercromby’s army deployed in long ranks across the front of the French line. Perhaps for a moment, even Montcalm could not believe his good fortune.

The advance guard of Rogers’s ranger companies, Gage’s light infantry regiment, and a battalion of Massachusetts light infantry moved forward to the edge of the abatis tangle, chased off a few French pickets, and set to sniping at any heads that poked up above the crest of the main fortifications. This, as the historian Fred Anderson points out, was at least some evidence that Gage, if not Abercromby, had learned a lesson or two from his days on the Monongahela. But the array of ranks spread out three deep behind them belied that education and showed that Abercromby “intended to use his most thoroughly disciplined troops in the most thoroughly conventional way: by arraying them in three long, parallel lines and sending them straight up against the French barricade.”28

It was noon by the time eight regular regiments, backed by six provincial regiments in reserve, dressed their ranks and prepared to advance into the hornet’s nest. Then, to the beat of drums and swirl of bagpipes—the Highlanders Black Watch regiment was in the center of the line—the thin line started across the field.

The Black Watch was another of Pitt’s controversial military experiments. The Scots Highlanders had long proved that they were fighters, but now that they were finally a lasting part of the British Empire, Pitt determined that they should use their bravery fighting for it, not against it. To the generation of English military leaders who had fought against certain Scots at Culloden only a decade before, it was a shocking proposition. A Highlander regiment had acquitted itself well with Wolfe at Louisbourg, and now the Black Watch was about to prove its mettle before Carillon.

Onward they came. What discipline, what courage, what waste! Regiment after regiment approached the edge of the abatis and disintegrated, torn from its formation by the tangle of fallen timber and struck down by the hail of bullets from the fortifications. March up briskly, rush the enemy’s fire, and pour volleys into the trenches behind the breastworks, Abercromby had ordered. But the advancing regiments were chewed up long before they reached it. “Our orders were to [run] to the breastwork and get in if we could,” a survivor recalled, “but their lines were full, and they killed our men so fast, that we could not gain it.”29

And what of the Black Watch, the Highlander regiment that some had questioned as “Pitt’s grand experiment”? In the center of the British line, the Black Watch had taken “as hot a fire for about three hours as possibly could be,” all the time seeing nothing of the French “but their hats and the ends of their muskets.” Casualties were appalling. By one count, out of approximately 1,000 men, the regiment lost 8 officers, 9 sergeants, and 297 soldiers killed and 17 officers, 10 sergeants, and 306 soldiers wounded—a horrific casualty rate of 65 percent. Among those wounded was fifty-five-year-old Major Duncan Campbell.30

Those are the facts. Here is the legend. After the last gasp of the Stuarts at Culloden, a man with torn clothing and a kilt covered with blood appeared at the gate of the venerable castle of Inverawe on the banks of the River Awe in the western Highlands. The laird of the castle who answered the summons was Duncan Campbell. The stranger confessed to having killed a man in a brawl and pleaded for sanctuary from his pursuers. Campbell vowed that he would provide it and even acknowledged the stranger’s plea that he so “swear on your dirk.”

Scarcely had the stranger been safely hidden then there came another pounding at Inverawe’s gate. Two armed men confronted Duncan Campbell with the news that his cousin, Donald, had been murdered and that the killer was fleeing before them. Much distressed, Duncan denied any knowledge of the unwanted guest he had sworn on his dirk to protect and sent the men away.

That night sleep came hard to the laird, but when it finally did come, he was confronted by the ghost of his murdered cousin standing beside his bed. The figure implored Inverawe to “shield not the murderer.” In the morning, Duncan went to the stranger and asked him to leave. “But you have sworn on your dirk,” came the stranger’s reply. Now, even more distressed, Campbell led him out of the castle and hid him in a nearby cave. That night the same ghostly presence returned to his bedside and once more implored him to “shield not the murderer.” In the morning, Campbell hastened to the cave to oust his unwelcome guest, but the murderer was gone. Once again that evening, sleep came fitfully, but the ghostly vision of his departed cousin returned a final time. “Farewell, Inverawe,” was all that he said, “Farewell, till we meet at Ticonderoga.”

The strange name, so the story goes, dwelled on Duncan Campbell’s mind until a few years later, when, as a major in the Black Watch, he found himself rowing toward Ticonderoga. On the night before the attack on the abatis, the ghostly vision of his cousin appeared to him again. In the morning, despite well-meaning comrades who tried to dissuade him from his gloom, Campbell averred, “This is Ticonderoga. I shall die today!”

Major Duncan Campbell survived the day, but died of his wounds nine days later in the hospital at Fort Edward. He now lies buried in the Union Cemetery in Fort Edward. The legend may be denied, but what cannot be denied is that Abercromby’s misuse of these brave and loyal troops was enough to give any Scot nightmares.31

Back at the sawmill camp, Abercromby had heard the terrible din of battle, but had not dared to venture forward to witness it. Lord Howe had lost his life by being willing to lead his army. Abercromby almost lost his army by refusing to lead it. By late afternoon there was a panicked retreat back to the landing site on Lake George. Upwards of 2,000 troops had fallen dead or wounded, and rumors abounded that the French were counterattacking and about to drive the rest into the lake.

At some point it must have dawned on even the blundering Abercromby that he had not only lost a large portion of his army but opened a gaping hole in the New York frontier. Far from taking any blame himself, however, he simply reported to Pitt that “it was therefore judged necessary for the preservation of the remainder of so many brave men, and not to run the risk of the enemy’s penetrating into His Majesty’s dominions, which might have been the case if a total defeat had ensued, that we should make the best retreat possible.”32

After such a misinformed and imprudent attack with such resulting death, it is hard to speculate what “a total defeat” might have been. Official returns later put the total number of British casualties at 1,944—of which 551 were killed; 1,356 were wounded; and 37 were missing. The majority of the casualties were regulars. French losses were 106 killed and 266 wounded.33

Dawn on the morning of July 9, 1758, found the largest British army yet assembled in North America rowing with all its might back up Lake George. The images of fluttered banners and glistening bayonets had been replaced by chaos. Ironically, the British were fleeing an army that was but a quarter of the size of their own and that was not in pursuit. Montcalm was more than content to maintain his position at “the place between the waters” and declare victory.

In fact, Montcalm was ecstatic, and his ecstasy caused him to misstate the facts in a letter to his wife. He had not stopped an army of 25,000 and had not inflicted 5,000 casualties, as he wrote to her; but just the same he had saved New France for another summer. Later Montcalm wrote to a friend: “The army, the too-small army of the King, has beaten the enemy. What a day for France! If I had had two hundred Indians to send out at the head of a thousand picked men under the Chevalier de Lévis, not many would have escaped. Ah, my dear Doreil, what soldiers are ours! I never saw the like. Why were they not at Louisbourg?”34

Why indeed, but the far more pressing question was why Abercromby had rushed headlong into defeat with an abandon that even Braddock had not evidenced on the Monongahela. Two contemporary poems emerged from the carnage to offer their authors’ own explanations. One bemoaned the loss of Lord Howe:

Illustrious Man! Why so intrepid brave.

Since thine was like to prove the army’s grave?

Could not that love for us, that led thee on,

Show, that by losing thee, we were undone?

Why was that life in which our hopes were centered,

So much exposed, and too, too much adventured?

Of arms and arts and all that’s good a mirror;

Thy too much braveness was thy only error,

Now rest in joy a peace and let thy name

Ascend illustrious in the sphere of fame.35

The other poem was written by Montcalm himself and inscribed on a great cross that he ordered erected on the battlefield the morning after the battle:

To whom belongs this victory?

Commander? Soldier? Abatis?

Behold God’s sign! For only He

Himself hath triumphed here.36