Basking in the triumph of his victory at Louisbourg, Major General Jeffery Amherst considered his next move. Thanks to the stubborn if somewhat reluctant defense of Louisbourg by the French navy, half of the summer of 1758 had passed before the town’s capitulation. The days were growing shorter. Amherst’s redheaded, hot-tempered young brigadier, James Wolfe, advocated pushing on to Quebec no matter what the season, but Amherst was uneasy about how his commander in chief, Major General James Abercromby, was faring north of Albany.

Then on August 1 “came the news which Amherst had feared, only ten times worse. Abercromby had been not only defeated at Ticonderoga, he had been slaughtered.” With their Lake Champlain front secure, it now seemed that the French could concentrate their forces against any army that Amherst might send up the Saint Lawrence, or they could advance on Albany at their pleasure. Amherst and Admiral Boscawen held a hurried conference and reluctantly wrote a joint report to Pitt detailing the impracticality of attacking Quebec that summer. Rather than sail for Quebec, Amherst would rush to Abercromby’s aid, while Wolfe was given the rather unpleasant task of destroying generally unarmed French fishing villages on the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.1

Meanwhile, on the southern shores of Lake George, Abercromby took stock of his own situation. What Wolfe characterized as “the unlucky accident that has betaken the troops under Mr. Abercromby,” was much more than that. Although Montcalm did not mount a major offensive southward in pursuit, he did send about 1,000 men around the eastern side of Lake George to disrupt Abercromby’s lines of communication between the lake and Fort Edward. The French fell on a wagon convoy and killed 116 men, sixteen of whom were rangers. Rogers was dispatched with a party of about 700 men, including rangers, Connecticut provincials under the command of Major Israel Putnam, and some of Gage’s light infantry, to cut off their retreat.

The main French force eluded him, but as Rogers returned to Fort Edward, other French troops attacked and Major Putnam was among those taken prisoner. After about an hour’s fighting, Rogers nonetheless claimed that “we kept the field and buried our dead.” All this left Abercromby feeling quite vulnerable, particularly because he had finally given Colonel John Bradstreet permission to undertake a daring plan that Bradstreet had been promoting for at least three years.2

By most accounts John Bradstreet was a doer, a man of great energy and personal courage who had worked his way up the hard way. He seems to have been driven by an insatiable ambition that occasionally found him crossing the line into dubious activities. “John Bradstreet,” wrote the historian Harrison Bird more succinctly, “was a bateau man.”3

Indeed, no one had mastered the use of those ugly flat-bottomed boats for operations or logistics more effectively than John Bradstreet. The wooden boats certainly weren’t pretty to look at or elegant under way—propelled by oars, makeshift sails, or both—but in this war in this roadless wilderness, bateaux were the counterparts of modern half-tracks or Bradley fighting vehicles. One bateau was capable of transporting twenty-five men and supplies along watery routes for great distances.

John Bradstreet was born in Nova Scotia in 1714, the son of a British army lieutenant and an Acadian mother. From the age of fourteen onward, he took the British army as his avenue of promotion, and he steadfastly stuck with it despite agonizingly slow advancements. At a chance meeting with Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts in 1744, Bradstreet impressed Shirley with his intimate knowledge of Nova Scotia and may have persuaded Shirley that an attack on Louisbourg could be successful. When Shirley sent William Pepperell’s expedition in that direction the following year, Bradstreet was in the thick of things. Bradstreet remained in the British army after the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle and seems to have relied on his mother’s Acadian roots to carry on questionable trading practices—if not outright smuggling—with the French while he was a British officer.4

By 1755, Bradstreet was a captain, and from Oswego he reported to Governor Shirley—by then commander in chief in North America—that the French were marshaling their forces at Fort Frontenac on Lake Ontario and were likely to attack Oswego. “Frontenac” was a name that Bradstreet would come to repeat time and time again.5

The following year, observing that operations at both Lake George and Oswego had suffered in 1755 “for want of a sufficient number of wagons, horses, and bateaux-men,” Shirley informed his superiors in London that he had taken steps to prevent the same from happening again. “I gave orders for engaging 2,000 bateau-men to be disposed into companies of 50 men each under the command of one captain and an assistant, and to be put under the general direction of one officer well skilled in the many branches of this important trust.”

In other words, Shirley had found someone who not only knew about boats and logistics but also knew how to fight. That man proved to be John Bradstreet. Shirley promoted him to the rank of lieutenant colonel and put him in charge of bateau service on the Mohawk River, essentially the supply line between Albany and New York’s western outposts, including Oswego.6

If nothing else, this proves that Shirley—despite subsequent criticism—understood that a wilderness war could never be won without reliable lines of supply. These tasks had to be undertaken not by unarmed teamsters and boatmen, but by men able to fight their way through no matter what the terrain or the opposition. When Oswego fell in the summer of 1756, Shirley bore the brunt of the blame, but not because of any problems with supply: six weeks earlier Bradstreet’s bateaux convoy had “thrown into Oswego six months provisions for five thousand men … and defeated a party of French and Indians on his way back.”7

Throughout these years of lackluster British military achievement in New York, Bradstreet performed admirably and sang but one song: Frontenac. Never mind Britain’s loss of Oswego, or Webb’s failure to reinforce Fort William Henry the following year. Bradstreet wanted to lead a daring raid against the hub of New France’s own western supply line—Fort Frontenac. No doubt it was at Bradstreet’s urging that first Shirley and then Lord Loudoun were inclined to strike this way, but the exigencies of the moment always prevented them from turning Bradstreet loose.

Never shy about stating his own qualifications or promoting his own advancement, Bradstreet continued to beat the drum not only for an assault on Frontenac, but also for an attack from there down the Saint Lawrence to Montreal. Mincing no words, Bradstreet unabashedly proclaimed: “Were it not owned by all degrees of people that no person in America is more capable of conducting an inland expedition in these parts than I am, I would by no means be so presumptuous as to offer myself as a candidate for the command.”

Bradstreet continued, “I know and am sensible of the distance, difficulties, and dangers which would attend it, and believe few there are who think it practicable, but … so far am I convinced of my being able to go through with it that I will risk my reputation upon the success of it as far as the taking of Montreal and all the forts upon the lakes and join the fleet should they reach Quebec—unavoidable accidents excepted.”8

This was bold talk, particularly as the war in North America seemed to be filled with “unavoidable accidents,” but Bradstreet was continually diverted to other missions. Most recently, Abercromby had summoned him to Ticonderoga. Bradstreet had been in the vanguard there with Rogers and Howe, and his bateau men had done yeomen’s service marshaling Abercromby’s army forward and shepherding its retreat. Now, after the staggering setback, Abercromby “was looking desperately for something that might soften the bitterness of his defeat.”

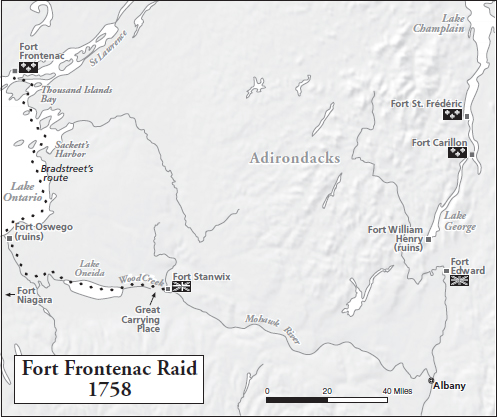

Once more, Bradstreet pleaded his case for an attack on Fort Frontenac. On July 13, 1758, Abercromby agreed. Bradstreet was directed to proceed up the Mohawk and assist General John Stanwix in the construction of what would become Fort Stanwix at the “great carrying place,” the portage between the Mohawk River and Lake Oneida. This effort was designed to counter the threat of a French invasion down the Mohawk—the very operation that New France’s governor general, Vaudreuil, had talked of earlier in the spring. It would also reestablish in the area a British presence that had been lacking since the fall of Oswego and would serve to renew Iroquois confidence in Great Britain. These objectives were openly discussed and waved about rather freely. Only Bradstreet seems to have known that he also had Abercromby’s permission to proceed beyond these defensive actions and at long last take the battle to the gates of Fort Frontenac.9

Fort Frontenac, like most North American fortifications of this era, was not an impregnable citadel—far from it. But its strategic location where Lake Ontario empties into the Saint Lawrence River could not be denied. It was the crossroads of the western half of New France. Eastward, the Saint Lawrence funneled to it a singular lifeline of supplies and what sustenance Quebec and Montreal could spare.

Westward—ah, westward; that was the key. From Fort Frontenac westward, French supply lines and the accompanying influence of the French fanned out like water from a sprinkler. Indeed, Fort Frontenac was the faucet that dispersed goods to frontier posts from Fort Niagara and points south, including the Allegheny portage to Fort Duquesne, all the way westward to Fort Michilimackinac. In return, the riches of New France’s far-flung fur trade passed through Fort Frontenac and were funneled in the opposite direction down the Saint Lawrence to Montreal.

Count Frontenac, as the newly arrived governor general of New France, had established the fort in 1673 and named it for himself. Count Frontenac was eager to extend French influence on Lake Ontario by controlling its outlet, as well as to establish a line of some resistance that would both keep the Iroquois south of the lake and protect the French fur trade. Six years later, the French built Fort Niagara on the lake’s inlet from the Niagara River and Lake Erie in an effort to extend this buffer. These efforts met with limited success, of course, and in time the British constructed the post at Oswego in response.10

Lulled by eighty-five years without a direct major attack, Fort Frontenac had grown far more commercial than military in nature. Arranged in the form of a square with bastions at the corners and stone walls about one hundred yards in length, its interior accommodated officers’ quarters, barracks, a chapel, and the requisite powder magazine. Some thirty cannon graced the ramparts with another thirty held in reserve, but the fort’s real treasure lay outside its walls in the great storehouses filled with goods at the water’s edge. Frontenac was less militarily prepared than either Fort Niagara or Fort Duquesne, but each of these outposts owed its survival to the supplies that passed through Frontenac’s wharves.11

As Bradstreet assembled his troops and headed up the Mohawk in August 1758, the makeup of his force was no secret. “Colonel Bradstreet is to command in an expedition this way of 3,000 men,” noted a report from the Great Carrying Place dated August 13. His army was to include only 155 regulars and rely on provincials numbering as follows: “New York, 1,112; New Jersey, 412; Boston, Col. Williams, 432; Boston, Col. Doty’s 243; Rhode Island, 318”; and, of course, 300 or so of his fellow bateau men. Where they were headed, however, was still supposed to be a closely guarded secret. A train of eight artillery pieces and three mortars “go into Wood Creek this day” from the portage with the remainder of the army to follow the next, but their destination “is not known to any mortal here, except General Stanwix.”12

That was probably not entirely true, particularly as a report a few days later made mention of very low garrison strength at Fort Frontenac and suggested that “they were not in the least suspicious of any army coming that way this year.” It was possible, of course, that Bradstreet might strike westward and attack Fort Niagara instead, but regardless of the final destination, as his forces assembled and moved out, two things were certain.13

First, the Onondaga and Oneida from the Six Nations whom Bradstreet had encouraged to join in the expedition as allies quickly became convinced that its purposes were far more aggressive than merely building a fort at the Great Carrying Place. Unwilling to carry the fight against posts where they frequently traded, most Indians quietly deserted the campaign. The second certainty was that the French, transfixed by operations at Louisbourg and Fort Carillon, were almost totally unprepared against any offensive operations on Lake Ontario. Not only had they left the back door largely unguarded; they had left it standing wide open.

So Bradstreet’s bateau navy sped his little army down Wood Creek to Lake Oneida and then down Oswego Creek to Lake Ontario. Arriving there on August 21, they found only the ruins of the British post that Montcalm had captured and destroyed two summers before. The next morning, its destination now becoming obvious to all, the flotilla rowed thirty-five miles northward along the eastern shores of Lake Ontario to Sackets Harbor, where it paused to regroup. (Montcalm had used this quiet bay to similar advantage when he attacked in the opposite direction.)

Concerns ran high that any number of French vessels known to be on the lake might chance on the convoy of more than 100 bateaux and whaleboats and scatter it with cannon fire, but no French sails appeared. On August 25, after another twenty-five miles, Bradstreet’s bateaux nosed ashore about one mile west of Fort Frontenac and landed their cargoes of troops, artillery, and supplies without opposition.

The French commandant at Fort Frontenac was Major Pierre-Jacques Payen de Noyan. He had spent forty-six of his sixty-three years in the service of his king in the French marines and was about to undertake his last official act. Forewarned several days earlier by his own Indian allies of Bradstreet’s advance, Noyan had sent a messenger hurrying to Montreal to beg Governor Vaudreuil for any and all assistance. The governor immediately summoned militia from the fields where they were harvesting the crop that was New France’s lifeblood and started them up the river toward Fort Frontenac. Meanwhile, Noyan mustered his forces and looked west from the fort’s ramparts.

By the morning of August 26, Bradstreet’s artillery was in place about 500 yards west of the fort. These pieces began a bombardment limited by the quantity of ammunition available. The French replied for show, but any real effect was limited on their side as well by a lack of troops to man all the fort’s cannons. Unsure of how many troops Noyan had inside Frontenac, Bradstreet no doubt also had visions still fresh in his mind of Abercromby’s frontal assault at Ticonderoga. Bradstreet did not order a direct attack. Instead, his troops advanced to an old line of defensive breastworks about 250 yards from the fort and then hauled two twelve-pounders to the top of a small hill only 150 yards from Frontenac’s northwest bastion.

At dawn on the second morning, Bradstreet’s artillery began to pour a pounding barrage against the fort’s crumbling, eighty-five-year-old stone walls. “Being so near,” wrote an officer in the New York regiment, “every shell did execution.” The French cannon responded, but Noyan knew that he was doomed. There was no sign of relief from Montreal. Concerned for the large number of women and children in the fort and with no chance of overcoming Bradstreet’s overwhelming odds in manpower, Noyan struck his colors. He lowered the white fleur-de-lis and ran up a red flag of surrender, which the French used to differentiate such a request from their national ensign.

Bradstreet wasted no time. Noyan’s meager garrison—which totaled only 110 men at the time of the surrender—could keep their money and their clothes, but they were to return to Albany as prisoners of war until exchanged. The real prize, Bradstreet knew, was in the storehouses along the docks and in the holds of nine captured ships—two snows, three schooners, three sloops, and a brigantine.* Inexplicably, they had remained tied to the dockside rather than fleeing before Bradstreet’s artillery could be hauled into position. Seeing the fort capitulate, the crews of the brigantine and a schooner attempted too late to get under way, but British cannon fire interrupted their escape. The French sailors quickly abandoned their ships and fled to shore in small boats. The brigantine and the schooner were left to drift, coming aground several miles away, and Bradstreet’s men soon retrieved them.14

Not knowing when Governor Vaudreuil’s Montreal militia might appear, Bradstreet’s men quickly fell to work salvaging appropriate plunder before demolishing the fort. “It had in it a vast quantity of provisions, which we burned in the fort, and everything else that the French left, and we could not bring away,” an officer from New York reported.

By one account, “2000 barrels of provisions”—flour, beef, and pork—went up in smoke. The two snows, the three sloops, and two of the schooners were also burned to their waterlines. Now, even if other provisions could be found, there was no way for the French to transport them to the western posts of Fort Niagara and Fort Duquesne. Even Bradstreet did not realize at the time how many of the hopes of New France were disappearing into the late summer sky amid the black smoke.15

By the afternoon of the following day, August 28, Bradstreet was anxious to be on his way. He amended the terms of surrender slightly and now permitted Noyan and his soldiers and their families to proceed directly to Montreal, on Noyan’s promise to arrange for the release of a like number of British prisoners. This was not a noble gesture but merely Bradstreet’s way of ridding himself of unnecessary baggage so that he might do what he did best: move fast. With all the plunder his men could gather loaded into the captured brigantine and schooner, Bradstreet ordered his fleet of bateaux and whaleboats back onto the lake.

“I have the pleasure to inform you,” wrote one of his lieutenants just two days later, “that I arrived here [Oswego] this day, with a brig under my command, deeply loaded with furs, skins, bale goods, liquors, etc. The brig is the same that was taken from us by the French at Oswego two years ago.”16

By the time that Governor Vaudreuil’s militia finally reached the charred ruins of Fort Frontenac, Bradstreet had also arrived at Oswego and was once more hauling his wooden fleet back to the Great Carrying Place. His troops had suffered the loss of only one man killed and a dozen or so wounded.

Bradstreet immediately hurried on to Albany and pleaded with General Abercromby to allow him to conduct a similar raid against Fort Niagara. Had the bateau man known that the French garrison there numbered but forty men, he might have relied on the odds of a speedy victory, raided without Abercromby’s permission, and then simply begged forgiveness. But now, having asked the question, Bradstreet was bound by the old plodder’s answer. Abercromby—clearly not recognizing the strategic coup that Bradstreet had just wrought—said no. Niagara would have to wait for another year.17

Earlier that spring, Brigadier James Wolfe, who was so critical of so many, had already written of Bradstreet, apparently without ever meeting him, “Bradstreet for the bateaux and for expeditions is an extraordinary man.” Now, he rendered his postmortem. “Bradstreet’s coup,” wrote the general who still dreamed of Quebec, “was masterly.”18

Eighty miles north of Albany, Montcalm stood on a parapet at Fort Carillon as a chilly wind of early fall blew across Lake Champlain. It was now his turn to ponder his fate. The couriers of September 6 had not brought good news. In a double blow, Montcalm learned simultaneously of the defeats at Louisbourg and Fort Frontenac.19 What good was his own victory now? Had it indeed been providence, Abercromby’s stupidity, or just plain luck?

Replacing Lord Loudoun with General Abercromby may not have been one of Pitt’s shrewdest moves, but it seems to have had one definite impact in the field. Loudoun had planned to move against Fort Carillon in late May—a time when both the lack of provisions and the melting snows would still preclude speedy deployment of French troops from their winter quarters in Montreal and Quebec. Montcalm did not march south with the bulk of Carillon’s reinforcements until after the arrival of the first supply ships in late June. By the time Abercromby finally struck north, it was early July. Had the British appeared at Carillon’s gates a month earlier, they would have found it in a state of readiness similar to that which had just greeted Bradstreet at Fort Frontenac.20

But no matter to whom he owed his victory, Montcalm had it. On the very evening that he received the news of Louisbourg and Frontenac, he set out for Montreal to confront the man he had come to feel was as grave a threat to New France as any invader—Governor Vaudreuil. Abercromby had blundered badly below Carillon’s entrenchments, and this had cost him 2,000 casualties and another summer. But Vaudreuil had been caught napping on Lake Ontario, and that had cost him not only the vital provisions of Frontenac’s storehouses but—more important—the lines of supply to both Fort Niagara and Fort Duquesne. Montcalm was determined to do all that he could to repair the damage.

At first glance, Bradstreet’s raid seems to pale beside the grand siege of Louisbourg and the carnage at Ticonderoga. But closer scrutiny suggests that quite possibly this little-known affair might have been the death knell of New France. After all, it was not the loss of Louisbourg alone that threatened New France. With a more powerful navy, France might have saved Louisbourg or ended up trading it back and forth again as in the past. On the Lake Champlain frontier, New France’s boundaries had remained essentially unchanged for four years running—admittedly, thanks in part to Abercromby’s blunders. But Frontenac was different. It sat astride the main artery that sustained not only Niagara and Duquesne but also all of the upper Mississippi and Ohio valleys. It sat astride New France. Time would soon tell, but the bateau man had indeed taken a huge whack out of the trunk of the tree.