We left Brigadier James Wolfe in August 1758, as he was savoring the fall of Louisbourg and champing at the bit to sail up the Saint Lawrence River to attack Quebec. When Admiral Boscawen and General Amherst deemed the season too late and the news of Abercromby’s defeat at Ticonderoga too alarming to let them concur, Wolfe was instead dispatched with three regiments to burn French fishing villages on the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Observing in a letter to his father that his mission was “to rob the fishermen of their nets, and to burn their huts,” Wolfe reported to Amherst after the fact that “we have done a great deal of mischief—spread the terror of His Majesty’s arms through the whole gulf; but have added nothing to the reputation of them.” Then, without specific orders to do so, Wolfe left his officers and men at Louisbourg and abruptly sailed for England onboard Admiral Boscawen’s flagship.1

No one was more surprised to learn of his arrival there than William Pitt. After the fall of Louisbourg, Pitt dispatched orders that Wolfe was to remain in North America for the winter and prepare for the spring campaign—wherever that might be. Now, here was the young brigadier suddenly making the rounds between London society and his old regiment and, in Amherst’s absence, being hailed as the man of the hour for the capture of Louisbourg. Never mind that Wolfe had left there before Pitt’s orders to stay arrived—again, transatlantic communication was slow. The part most disconcerting to Pitt was that Wolfe had left Louisbourg without any orders.2

When military friends alerted Wolfe to his faux pas, the briefly humbled man of the hour wrote a short but ingratiating letter to Pitt alluding to his understanding that Lord Ligonier had previously agreed to Wolfe’s return to England after but one campaign season. Amherst, too, of course, had received similar assurances from Ligonier, but he had dutifully circled between New York, Boston, and Halifax waiting for the orders that deprived him of a winter’s respite in England. Now enjoying just that, Wolfe assured Pitt that he had “no objection to serving in America, and particularly in the river Saint Lawrence, if any operations are to be carried on there.”

If Wolfe was being coy in that last phrase, Pitt overlooked it, as well as his indiscretion in returning. Of course, there would be a campaign up the Saint Lawrence against Quebec, and for better or worse, Pitt had concluded that the soon to be thirty-two-year-old brigadier with the shock of flaming red hair to match his fiery ego was the man to command it.3

But Pitt kept Wolfe on the hook just a little while longer. “I am going directly to the Bath to refit for another campaign,” Wolfe wrote to a military comrade in reference to England’s most famous spa. If he knew where that campaign might be, Wolfe gave no indication, but he was not without his usual criticisms. “We shall look, I imagine, at the famous post at Ticonderoga,” Wolfe continued, “where Mr. Abercromby, by a little soldiership and a little patience, might, I think, have put an end to the war in America.”4

Soldiering, however, was not all that was on Wolfe’s mind at Bath. He renewed an acquaintance that he had made the previous year before sailing for Louisbourg. Her name was Katherine Lowther, and she was the daughter of a former governor of Barbados. Ten years before, Wolfe’s courtship of another woman had fallen flat, in part because of his absences in military service. “Young flames,” he confessed at the time, “must be constantly fed, or they’ll evaporate.”

Now, the matter seemed to take on far greater urgency for Wolfe at thirty-two than it had when he was twenty-two, and he pressed it with great vigor. What Miss Lowther saw in the gangly, thin, frequently fussy brigadier is open to conjecture, but his standing had certainly been raised over that of the previous year by his exploits at Louisbourg. For his part, Wolfe seems to have been transfixed by her captivating eyes. In the span of two months that were to be increasingly busy with military plans, Wolfe somehow found the time and the ardor to court her. He would leave England with both Katherine’s miniature portrait and her promise of marriage on his return.5

Just before Christmas 1758, Wolfe’s courtship of Katherine Lowther was interrupted by a summons to meet with Pitt at his country home. There, Wolfe finally received his orders for Quebec along with the temporary rank of major general in North America. Far from being humbled by the appointment, Wolfe got himself back into hot water almost immediately by adamantly insisting to Lord Ligonier that he had the right to name his own brigadiers. Ligonier acquiesced in two of Wolfe’s choices, but held firm with regard to George Townshend as the third, despite Wolfe’s threats. No wonder Wolfe was described as “intensely human, subject to error, not without vainglory, quick of temper, sanguine, emotional, vehement to a fault”—and this from the pen of a generally admiring biographer. To put it more succinctly, Wolfe was an odd duck.

To this point, there is an anecdote about Wolfe that must be told. Its details are perhaps dubious—or at least embellished—but its overall tenor is such that this same biographer proclaimed that it “by no means deserves to be rejected in toto.” On the eve of his departure for North America, Wolfe was invited to dine with Pitt and Lord Temple, Pitt’s brother-in-law, to receive, it is assumed, Pitt’s last-minute admonishments for the conduct of the coming campaign. As the evening progressed, Wolfe’s tongue was loosened more than normally by the wine. (It appears that as a rule he drank sparingly.) Not only did Wolfe freely offer his own sentiments on the task at hand, but “he drew his sword, he rapped the table with it, he flourished it round the room, [and] he talked of the mighty things which that sword was to achieve.”

Pitt and Temple sat speechless at the display. If Pitt had second thoughts about his chosen commander, he confided them only to Temple after Wolfe had departed. It was Temple who whispered of Wolfe’s conduct to the duke of Newcastle, who was still Pitt’s partner in government. Newcastle is supposed to have hurried to tell George II of Wolfe’s outburst as further evidence that Pitt’s cadre of young brigadiers was not to be trusted with the fate of the empire and that Wolfe in particular was quite insane. “Mad, is he?” retorted George, perhaps humbled by his insistence on the defeated Abercromby and the humiliation of his own son in Europe. “Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals!”6

We can take that with a grain of salt, but here is what happened next. Wolfe sailed from Portsmouth on February 14, 1759, onboard Neptune, the flagship of Vice Admiral Charles Saunders. In England, he had been promised some 12,000 troops, but by the time his army embarked for Quebec from Louisbourg, the number was closer to 9,000. All were regulars or Royal Navy marines with the exception of six newly raised ranger companies. Always a critic of the colonials, Wolfe labeled these North Americans “the worst soldiers in the universe.”7

After the dust had settled with Ligonier, Wolfe’s brigadiers were Robert Monckton, James Murray, and George Townshend. Monckton was the most experienced in North American affairs, having accomplished the only British success of 1755 with his capture of Nova Scotia’s Fort Beauséjour. Murray was perhaps an odd choice. Wolfe had had a run-in with him in Scotland years before, but after watching his service at Louisbourg as a regimental commander, Wolfe had praised him with a rare accolade, noting that “the public is much indebted to him for great service in advancing … this siege.”8

Townshend was more political than military in nature, but he had cut his teeth alongside Wolfe and Monckton at the battle of Dettingen so long ago. A falling-out with the duke of Cumberland left him out of the army for a time, but now Townshend seemed determined that some of Wolfe’s glory should rub off on himself. As both the nephew of the duke of Newcastle and a political ally of William Pitt in Parliament, Townshend was in easy touch with both sides of the Newcastle-Pitt marriage and could be counted on to report back to London any warts that might develop on Wolfe’s campaign. Of this quartet of Wolfe and his three brigadiers, Wolfe was the youngest by six months. In the end, all three brigadiers would come to detest him. And so, to Quebec they all sailed.9

Founded by Champlain as a permanent settlement in 1608, Quebec was the gateway to the heart of New France. The town’s very name told its geography. “Quebec” derived from an Algonquin word meaning “the river narrows here.” Indeed, it does. For 350 miles inland from the western tip of the Ile d’Anticosti, the Saint Lawrence estuary is fifteen, twenty, even thirty miles wide. Then, just below Quebec, faced by the plug of the Ile d’Orleans, it narrows upstream of the island to barely three-quarters of a mile.

The town stood on the northern shore atop a rocky promontory cut by the Saint Lawrence to the south and its tributary, the Saint Charles River, to the north. The promontory came to a point on its eastern side above the confluence of the two rivers and the waters of the Orleans Basin. Only to the west did the promontory widen beyond the city walls, rise to a shallow ridge, and then fall away gently across what was called the Plains of Abraham—not because of any biblical reference, but because one of Champlain’s river pilots, Abraham Martin, had settled there.

Quebec itself was divided into the Lower Town just above the river on a long, narrow strip that was crowded with docks, warehouses, and houses; and the Upper Town astride the tip of the promontory 300 feet above. The Upper Town was completely encircled by a stout wall, and its artillery commanded a wide sweep of the rivers below and plain to the west. On three sides the escarpment fell away from the walls in steep cliffs, while six bastions anchored the wall on its wide western side. No wonder Count Frontenac, when viewing the heights in 1672, exclaimed, “I never saw anything more superb than the position of this town. It could not be better situated as the future capital of a great empire!”10

Northeast of Quebec—the Saint Lawrence River maintains its generally southwest-to-northeast flow through here—there was a broad plain along the north bank of the river that extended three miles from the mouth of the Saint Charles to the little village of Beauport. Downstream from Beauport, the riverbank began to rise again the farther east one went until the cliffs crested at the 300-foot falls of the Montmorency River. West of Quebec—above the town in river parlance—the line of cliffs continued on the north shore with only a narrow break at a place called Anse au Foulon.

Stout though its position might appear geographically, Quebec in the spring of 1759 was in a sorry state. In many respects, it mirrored the rest of New France. “The harvest of 1758 had been the worst of the whole war in Canada, and the winter of 1758–59 the coldest in memory.” Once again, Quebec and much of Canada were starving. Without provisions from France, it would be difficult to mount a defense against any of the various avenues by which the British appeared certain to threaten.11

“If your winter proved melancholy, ours I assure you, has not been gay,” wrote one resident of Quebec to his brother-in-law in late April 1759. “We have been reduced to a quarter of a pound of bread per day, and have often had no meat at all…. In a word, every thing is above price: ’Tis a most melancholy circumstance to think what will become of us. It is my opinion, if peace does not immediately take place, or great succor sent us from France, our colonies had better submit to the English than continue in their present misery.” Now, there was little else to do but wait for the attack that all of Quebec knew was almost certain to occur.12

English attacks on Quebec were nothing new. In fact, the English had captured what was then a tiny settlement in 1629, only to have the town and surrounding country returned to France by treaty. Other attempts by the English to capture Quebec in 1690 and 1711 had failed, as had a more recent attempt in 1746. In each case the English had planned an assault up the Saint Lawrence and encountered varying degrees of calamity on it. In fact, the river was a gigantic bogeyman in legend, if not in fact. The very thought of sailing up the Saint Lawrence, with its changing tides and currents, unpredictable shallows and sandbars, and blinding fog made most Royal Navy captains shudder. “I believe the difficulties supposed to attend the navigation of the River Saint Lawrence to be more imaginary than real,” wrote Amherst to Pitt, but then the only waterway before Amherst was Lake George.13

The problem of the Saint Lawrence belonged to Vice Admiral Charles Saunders. His most recent assignment had been the blockade off Brest and his patron, First Lord of the Admiralty Anson, had tapped him for this important task. When the main British fleet at last weighed anchor and struggled forth in a light breeze from Louisbourg harbor early in June, it numbered 162 ships, including twenty-one ships of the line, five frigates, fourteen sloops, two bomb vessels, a cutter, and 119 transports loaded with Wolfe’s men and matériel. There had, however, already been one major naval setback.14

When Admiral Boscawen returned to England late in the fall of 1758 with the bulk of the British fleet, he ordered Rear Admiral Philip Durell to remain at Halifax for the winter with some fourteen ships of the line and frigates. Durell was to be prepared for offensive operations early the following spring. In December, Pitt wrote to Durell about the coming campaign up the Saint Lawrence and specifically ordered him to take up station off the mouth of the river in ample time to prevent reinforcements and supplies from France from reaching Quebec.

But when Saunders and Wolfe sailed into Halifax on April 30, Durell’s squadron was still in the harbor, held there by late ice floes in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence that were the result of the unusually bitter winter. (Wolfe, who had not been impressed with Durell’s actions off Louisbourg the summer before, thought that too easy an excuse.) By the time Durell’s ships finally reached the Saint Lawrence, two French frigates and a convoy of fourteen supply ships had managed to slip up the river and reach Quebec.15

The effect on the town was electrifying. Not only would its citizens have food, but Montcalm would also have provisions with which to mount a strong defense. Had Durell succeeded in intercepting this relief convoy, the general populace of Quebec might have had little choice but to open its gates at Wolfe’s arrival in order to avoid starvation.

So, with Durell’s squadron leading the way, Saunders’s main fleet sailed up the Saint Lawrence. It helped immensely that the navigator of one of the lead ships, Pembroke, was none other than a young lieutenant named James Cook, then still cutting his teeth but in time to become one of the Royal Navy’s most distinguished sailors. Between some captured Canadian river pilots, who were lured aboard the first British ships by a false display of French colors, and a bit of verve on the part of several captains, the British fleet passed upriver without the loss of a single ship and anchored off the Ile d’Orleans. Seeing such audacious seamanship, the French themselves were amazed. “The enemy,” reported Governor Vaudreuil, “have passed sixty ships of war where we durst not risk a vessel of a hundred tons by night and day.”16

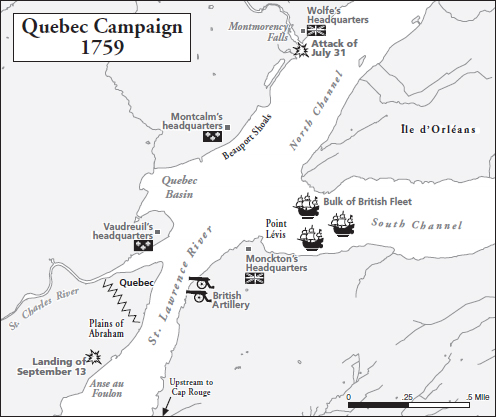

Less than five miles from his objective, Wolfe now made his opening moves in rapid succession. Troops landed on the Ile d’Orleans on June 26. Three days later, Monckton’s brigade went ashore at Point Lévis and soon seized the heights directly across the river from Quebec. By July 12 a battery consisting of four mortars and six thirty-two-pounders was placed on the heights within 900 yards of Quebec. “We opened our battery on the town,” wrote one British soldier, “which played its part very well, and soon set several houses on fire, which burned to the ground. The enemy returned the compliment as they could, but did us but little damage.” Two additional batteries were soon in place on Point Lévis. Meanwhile, elements of Murray’s and Townshend’s regiments had landed on the north bank downstream from Montmorency Falls.17

But Quebec was far from trembling. The British artillery fire was demoralizing to its citizens, but for the moment their bellies were full and they were content to wait behind its walls. Montcalm, commanding a force of some 14,000 French regulars, marines, Canadian militia, and a handful of Indians, was also content to wait. Rather than concentrate around a single stronghold such as the Upper Town, Montcalm had deployed his forces all along the wide Beauport shore where Wolfe had first proposed to land. His left flank was anchored more than five miles from Quebec by fortifications on the Montmorency River. West of the city, his right flank was protected by militia units stretching upriver another five miles to Sillery.

By spreading out his forces, Montcalm, the man who had successfully besieged Fort William Henry and held firm at Carillon, was determined not to get caught in a trap, but to leave himself with routes of retreat upriver with the bulk of his forces should Quebec fall. It required some communication—and perhaps a little intuition—to know where to mass his troops along this wide front in the event of a concerted attack, but let Wolfe come. Montcalm was content to wait.

James Wolfe had other ideas. The short northern summer was slipping away. Louisbourg had surrendered the year before on August 1, yet Quebec showed no signs of so speedy a fall. On July 31, determined to bring Montcalm into a full-blown engagement, Wolfe ordered a combined amphibious assault from the Saint Lawrence and across the Montmorency River against Montcalm’s left flank. It was a disaster.

Warned in advance by the thunder of a British naval bombardment, Montcalm calmly shifted troops to his left. A low tide was necessary for the land-based troops to cross the Montmorency below the falls and attack west, but the low tide also played havoc with the boats of the amphibious landing. Rather than massing on the beachhead—hotly under fire though it was—companies of disembarking grenadiers began a frantic attack inland, perhaps remembering the impetuousness of those Highlanders who had won the day in Gabarus Bay. But the grenadiers were cut down by concentrated French fire.

From then on, the combined attack faltered. Wolfe, himself no stranger to impetuosity, was highly critical of the behavior of the grenadiers; and by the time his troops stumbled back to their ships and the lines east of the Montmorency, he had lost 443 killed and wounded. Governor Vaudreuil was smug, but a little premature, when he intoned, “I have no more anxiety about Quebec.”18

Anxiety was about all that Wolfe had. Montcalm’s lines were stretched so wide and defended so well that Wolfe simply could not get in close enough to the walled city to dig the trenches and place the artillery that were customary in siege warfare. Frustrated and distraught by the dismal affair at Montmorency, Wolfe began to look upriver for alternatives.

As early as the night of July 18, two ships of the line, two heavily armed sloops, and two transports had passed beneath the guns of Quebec under the cover of a furious artillery barrage from Point Lévis. This foray had the effect of disrupting river communications and commerce between Quebec and Montreal and also gave the British a closer look at the northern side of the upper river. Montcalm had fortified this area well, and artillery at Sillery caused some damage to the command ship Sutherland.19

But operating on the upper river had its merits, particularly with regard to impeding the flow of arms and men between Canada’s two principal towns. To that end, on August 4, Wolfe dispatched Brigadier James Murray and 1,200 men upriver aboard a squadron commanded by Rear Admiral Charles Holmes. Murray was to probe the defenses on the north bank west of Quebec while Holmes was to frustrate any attempts the French might make to descend the river in their few remaining ships. On August 8, Murray met some stiff resistance on the north shore at Pointe aux Trembles, about twenty miles above Quebec. Next, he raided Saint Anthony across the river on the south shore and a supply depot at Deschambault farther upstream. French naval forces were content to retreat to the mouth of the Richelieu River draining Lake Champlain.

Perhaps the most welcome news that Wolfe received from Murray and Holmes on their return on August 25 (most of Holmes’s squadron remained on guard upriver) was information from several prisoners that General Amherst had prevailed against Ticonderoga and Crown Point. Fort Niagara, too, was in British hands. This was grand news, but why, Wolfe wondered, was there no sign that his commander in chief was striking north to apply pressure against Quebec from the south? The answer would become clear only in hindsight.

Amherst was busy reconstructing Fort Ticonderoga and building his new post at Crown Point. He was also awaiting the construction of a brigantine on Lake Champlain before making his way against the most recent line of French defenses at the Ileaux-Noix at the lake’s outlet. Not having heard from Wolfe since early July, Amherst was wary that Montcalm might yet appear in front of him with a unified army. As for help from Niagara, after learning of Prideaux’s death and Sir William Johnson’s confused assumption of command there, Amherst dispatched Brigadier Thomas Gage to take command of the newly won western posts. Gage may have been Amherst’s most able administrator, but he was never one to move quickly. He was content to secure the British gains and not run the risk of sending troops down the Saint Lawrence against Montreal. Wolfe, then, was on his own, just as he had been from the beginning.20

But by now Wolfe was dreadfully ill, his normally weak constitution ravaged by an assortment of fever, consumption, and an inability to urinate except with excruciating pain. The prescribed cures—bloodletting and opiates—did little to improve the clarity of his thinking. Recognizing that “the public service may not suffer by the General’s indisposition,” he summoned his three brigadiers to a council of war and asked their advice on one of three courses of action. It was the first time that Wolfe had done so, and his own decisions during the past two months had hardly endeared him to Monckton, Murray, or Townshend.

Now, Wolfe proposed three alternatives. First, ascend the Montmorency eight or nine miles and fall on the French rear above Beauport in concert with another attack west from the falls. Second, make a combined amphibious and land attack directly against the Beauport shore. Finally, replay the plan of July 31 and attack from the river and across the ford at Montmorency. Essentially, they were all variations of the same theme, and the brigadiers were not persuaded by any of them.

“General Wolfe’s health is but very bad,” wrote Townshend to a friend in England. “His generalship in my poor opinion—is not a bit better, this only between us.” Even fifteen years later, Murray was still writing to Townshend of Wolfe’s “absurd” fixation on attacking the enemy’s lines at Beauport.21

And even if they gained Beauport, could they cross the Saint Charles against Quebec? The brigadiers were unanimous in their counsel. All favored abandoning the Montmorency camp, transferring operations to the south shore, and moving upriver to force an open field battle with Montcalm by decisively cutting off his lines of communication and supply from Montreal. Reluctantly, Wolfe agreed. Of his failed plans at Beauport, Wolfe confided to Saunders the day after meeting with his brigadiers that “My ill-state of health hinders me from executing my own plan: it is of too desperate a nature to order others to execute.”22

During the first week of September 1759 more British men, ships, and matériel passed upriver of Quebec. Now, Montcalm had to make a decision. Was this another feint or the real thing? In addition to militia units, the key military force immediately west of Quebec was a 2,000-man contingent of cavalry and foot soldiers under the command of Montcalm’s trusted aide-de-camp, Louis Bougainville. This force was charged with shadowing the British fleet as it moved between Quebec and Pointe aux Trembles twenty miles to the west and coming to the aid of the militia units to repulse any attempted landing. For a time, the Guyenne battalion of regulars was also camped outside the city’s western gates to assist in these efforts. “I need not say to you, sir,” wrote Govenor Vaudreuil to Bougainville on September 5, “that the safety of the colony is in your hands.”

Montcalm, too, was concerned with his lines of both supply and retreat west of Quebec, but he was still far from certain that Wolfe would mount a major offensive from that direction. Having waited patiently at Beauport and at the Montmorency most of the summer, Montcalm saw these British movements upriver as just a diversion. Montcalm still believed as late as September 2 that Wolfe, “having played to the left [Montmorency], and then to the right [upriver], would proceed to play to the middle” directly against Beauport. And in fact, Wolfe may well have done this, had it not been for his brigadiers.23

By September 7, Bougainville’s force was moving from Sillery, just west of Anse au Foulon, and following British movements upriver to Cap Rouge, about eight miles above Quebec. Wolfe issued orders that Monckton would lead a major force ashore at Pointe aux Trembles on the morning of September 8, while other units would make a feint against Cap Rouge to hold Bougainville in place. But the weather turned stormy with torrents of rain and Wolfe countermanded the orders. Instead, some 1,500 troops were permitted off their transports and given a two-day respite on the southern shore.

During this time, Wolfe came up with a scheme much different from that previously discussed with his brigadiers. Taking a boat downstream on September 9 with Monckton, Wolfe spent hours reconnoitering the narrow gap in the cliffs at Anse au Foulon. He made similar observations on the following two days and by September 12 told Monckton that his troops would lead the assault against this point. Monckton was dubious, both because of the French positions atop the cliffs and because of the fact that Murray and Townshend had not been told what their roles might be. Was Anse au Foulon to be the main attack or merely a diversion?

Why and how Wolfe came to focus almost secretively on Anse au Foulon has long been a matter of debate. Wolfe’s admirers offer it as a testament to his genius and generalship. His detractors term it a desperate, last-ditch gamble in which Wolfe was determined to die rather than return to England in disgrace. Some say that Wolfe discovered the rocky defile himself, that he was told of it by a French deserter, or even that he learned of it from Captain Robert Stobo, who had achieved fame as a British spy at Fort Duquesne and had recently escaped from Quebec.

The truth may lie in a report from Admiral Holmes, whose ships would bear the burden of the naval operations. Holmes observed a few days after the battle that Wolfe’s “alteration of the plan of operations was not, I believe, approved of by many, besides himself.” According to the admiral, Anse au Foulon “had been proposed to him a month before, when the first ships passed the town, and when it was entirely defenseless and unguarded, but Montmorency was then his favorite scheme, and he rejected it.”24

Now, on the evening of September 12, Wolfe’s brigadiers sent him a joint letter pleading to be told his specific plans. Wolfe’s reply was indifferent, almost condescending: “It is not a usual thing to point out in the public orders the direct spot of our attack.” He had given the navy specific instructions for loading troops, into small boats. He himself would be in the van of Monckton’s troops and Monckton had already been told that his troops would lead the attack. If they were successful, Townshend was to follow, and presumably, Murray after him. What more did they need to know?

But as Wolfe gave these orders in his cabin aboard the Sutherland, it appeared that far from planning a grand victory, he was planning his own funeral. He had summoned a friend, Lieutenant John Jervis of the Royal Navy, who would go on to fame in the Napoleonic wars, and given Jervis his personal papers, a copy of his will, and the miniature portrait of Katherine Lowther. Set the portrait in jewels and return it to her with his compliments, the general commanded. He was dressed in a bright new uniform, and whatever infirmities he had recently suffered were momentarily put aside. Midnight came, and two lanterns appeared in the maintop of the Sutherland. It was time to go.25

The part of Wolfe’s legend that maintains that Anse au Foulon was the only possible spot west of Quebec where a landing might be forced is simply not true. Strategically and tactically, Pointe aux Trembles offered numerous advantages and at the time was guarded by only 190 men. By putting 4,000 troops ashore there, Wolfe could have moved eastward, dispensed with Bougainville’s smaller force at Cap Rouge, and completely cut Montcalm’s lines to Montreal.

Instead, Wolfe gambled on moving his army down the swift current of the Saint Lawrence in a flotilla of tiny boats, landing at one rocky spot, climbing in single file up a steep cliff, and forming on the plain above before they could be repelled. Perhaps Wolfe was a genius or, as the duke of Newcastle supposedly described him, “simply mad.” For his part, Admiral Holmes called the plan “the most hazardous and difficult task I was ever engaged in—the distance of the landing place; the impetuosity of the tide; the darkness of night; and the great chance of exactly hitting the spot intended, without discovery or alarm; made the whole extremely difficult.” But, evidently, it was not impossible.

Bougainville was still at Cap Rouge with more than 2,000 men. Admiral Holmes had been toying with him by having his ships float upriver with the high tide and then descend again with the ebb. Weary of following what had become a daily show, Bougainville settled in at Cap Rouge to await more concrete developments. Montcalm was east of Quebec at Beauport, still certain that whatever the British were doing upriver, it was part of an elaborate ruse, and that the main attack would come on the Beauport shore. Admiral Saunders did all that he could on the night of September 12 to confirm this opinion by lowering boats, placing buoys, and unleashing a heavy bombardment against these French positions in an elaborate ruse of his own.26

On the evening of September 12, 1759, as Wolfe made his personal preparations, about 4,000 troops embarked in flatboats on the south shore. Other ships made their daily float up to Pointe aux Trembles and then turned with the tide and under a favorable south wind raced back down river to join them. By two o’clock in the morning on September 13, the flotilla of boats, led by Wolfe and Monckton, was moving down the Saint Lawrence toward Anse au Foulon.

French sentries who heard the boats pass and might have spread the alarm were surprisingly gullible. Word had been passed along the river posts to expect a convoy of provisions from Montreal trying to slip past the British fleet in the dark of night. This must be it. When French challenges of “Who goes there?” from the shore were answered “Français,” there was no alarm raised.

At four o’clock in the morning thirty advance boats with about 1,800 men touched ashore at the base of Anse au Foulon and several points above and below it. Led by Lieutenant Colonel William Howe—the younger brother of Lord Howe, who had died at Ticonderoga—and followed closely by Wolfe himself, a detachment of light infantry clambered up the slopes to the plain above. If Howe, because of his own personal loss, had any misgivings about the presence of his commanding general in such a dangerous position, he gave no indication of it.

But the surprise was not complete, and when a small outpost of sixty Canadian militiamen opened fire, Wolfe sent orders down to the beachhead not to land any more troops. Was this his death wish or merely confusion again, as when he waved his hat in Gabarus Bay before Louisbourg?

Whatever the answer, it didn’t matter. Wolfe’s adjutant, Major Isaac Barré, disregarded the order and continued to urge the thin line of troops up the winding path. Meanwhile, Montcalm heard the firing west of the town but sat transfixed on the Beauport shore, thinking that the commotion upriver must be from an attack on his provision convoy. Even an early report that the British were in possession of Anse au Foulon was deemed to be suspect. Just the same, Montcalm ordered the Guyenne battalion, lately posted at Beauport, back to its position just west of Quebec.

Finally, mounting evidence convinced Montcalm that he himself should ride to the sound of the guns and take with him as many troops as he could muster. By the time Montcalm reached the crest overlooking the Plains of Abraham with some 4,500 regulars and militia, Townshend’s second wave had come ashore at Anse au Foulon and bolstered Wolfe’s force to more than 4,000.27

Much has been said by British writers about the glory of Wolfe’s “thin, red line” stretching across the verdant Plains of Abraham on that cool, misty September morning. Just as much has been written from the French side to the effect that as Montcalm beheld this, he and all of New France trembled and foresaw their doom. But should they have?

The year before, Montcalm had waited patiently for Abercromby’s hideous blunder before Ticonderoga. There was no tangle of abatis to hide behind on the Plains of Abraham, but Wolfe had not even moved his line forward to seize the high ground in the middle of the plain. Having sent a messenger to Bougainville urging him to rush from Cap Rouge and fall on the British rear, why didn’t Montcalm wait for him? At the very least, why didn’t Montcalm wait to be attacked by British ranks moving uphill? Incredibly, after waiting patiently all summer and refusing to engage Wolfe in a major battle, Montcalm moved with alacrity to do just that. If Wolfe seemed determined to die trying to capture Quebec, Montcalm now seemed resigned to the fact that he must die defending it.

And so, in this most unconventional of wars by European standards, the centerpiece battle was to be fought in the most conventional of European styles—two long lines of opposing forces, one rushing forward, the other content to stand tall and fire away. Once Montcalm had decided to attack, the topography of the plain gave him little option but to do so in a frontal charge.

The British line was stretched from the heights above the Saint Lawrence for almost half a mile to the bluffs above the Saint Charles. At five minutes to ten on the morning of September 13, 1759, about 2,000 French regulars, their ranks thinned by years of service in North America; and some 1,500 Canadian militia started forward with a great cheer. “It was,” the historian Fred Anderson wrote, “almost the last thing they would do in unison that day.”

At about 150 yards from the British position, the French troops, their ranks already in some disarray, dropped on one knee and fired a volley by platoons into the British line. Standing on a rise on the right flank with the Louisbourg Grenadiers, who had prematurely rushed into action at Montmorency, Wolfe was among the first to be hit, sustaining a shattered wrist. Reloading, the French line moved forward to close the gap. No one in the British line had yet fired a shot.

Onward the French came. At about sixty yards the British right and left flanks opened fire by platoons, but the Forty-third and Forty-seventh regiments in the center gave the onrushing ranks another twenty yards. Then, with the French attackers only forty yards away, the center of the British line exploded in a single volley that staggered the French advance and stopped it cold. As the British reloaded, the French units disintegrated and beat a hasty retreat.

Wolfe, apparently not content to be merely the victor, ordered a bayonet charge in pursuit and fell mortally wounded with wounds in his chest and intestines. Montcalm, too, had fallen, his abdomen and leg ripped open by grapeshot. Wolfe would expire on the field, Montcalm early the following morning.

As the British surged toward the walls of Quebec, their lines and discipline deteriorated, thanks in part to a concentration of fire from the remaining Canadian militia in a cornfield on the French left. Quite suddenly, there was mass confusion. Wolfe was dying or already dead. Monckton lay injured. Barré was incapacitated with a face wound. Murray was bogged down in a fight with arriving reinforcements above the Saint Charles, and the advance units of Bougainville’s column were appearing to the south.

Command devolved on Brigadier Townshend, who suddenly found himself in the military role he had sought. Townshend hastily dispatched orders to regroup. Seeing this coalescence begin, Bougainville held up his attack and withdrew to the safety of the Sillery Woods. His arrival an hour earlier, or Montcalm’s wait of an hour, might have led to a far different story.28

Not surprisingly, Governor Vaudreuil was among the critics who charged that Montcalm had acted “precipitately.” But he was not alone. One French officer wrote that “it was the judgment of everyone that had Montcalm awaited the arrival of Bougainville, so that the combined forces could have struck the enemy, not an Englishman would ever have re-embarked.” It would have been a classic pincer movement. Instead, it was the classic blunder of largely uncoordinated units of ill-trained militia and regular battalions long removed from the discipline of European battlefields rushing forward against a solid line. Vaudreuil had wanted to use these men to defend New France with frontier tactics across a wide region. Now, Montcalm had assembled them to fight a very different kind of battle and had met with disastrous results.29

By one count the British lost sixty men killed and 600 wounded. The French lost 200 killed and 1,200 wounded. The death of each side’s commanding general left history with two pithy quotations: Wolfe glad that he could die happy in victory and Montcalm appeased that he would not live to see the English masters of Quebec. The latter, of course, was now about to happen.

Vaudreuil and his militia and Bougainville and his force retired westward toward Montreal. The commandant of the garrison at Quebec, Jean de Ramezay, was left with an assortment of about 2,200 soldiers, sailors, and militiamen and three days of rations with which to defend the town and its 6,000 frightened inhabitants. Vaudreuil had no misconceptions about the outcome and left Ramezay instructions to surrender when his provisions ran out.

But in retrospect, this action by Vaudreuil appears to have been hasty, too. The chevalier de Lévis, who heretofore had been charged with protecting Montreal from Amherst, rallied the retreating troops and marched back toward Quebec with eighty carts of provisions and as many as 5,000 men. This relief force, which may well have played havoc with Townshend’s dwindling numbers, was only a dozen miles from Quebec when word reached it that Ramezay had surrendered on the afternoon of September 17.30

The following day a detachment of the Royal Artillery and the Louisbourg Grenadiers marched into the Upper Town and raised the Union Jack over the citadel of Quebec. In many respects it was a frighteningly hollow victory. The British immediately granted the French troops safe passage to France with full honors of war—not as prisoners—and permitted the militiamen to lay down their arms and rejoin their families. Most of the regulars were delighted to leave; but far from being magnanimous, the British were being practical. They simply did not have the troops to impose harsh terms. And their numbers were about to grow even smaller.

On October 18, Admiral Saunders and the bulk of the British fleet weighed anchor and sailed for England before another winter’s ice claimed the Saint Lawrence. Brigadier Monckton chose to go to New York to recover from his wounds; Brigadier Townshend elected to return to England, no doubt in order to look after his political health. That left James Murray, the junior brigadier, to take on the thankless task of presiding over the winter garrisoning of Quebec.

Perhaps no circumstance emphasized the tenuousness of Wolfe’s victory more than the situation in which Murray now found himself. The British fleet was gone, an able French army lurked just to the west, and Quebec was effectively cut off from all aid and succor. The British may have captured Quebec, but what they had really done was to trade their position as attackers and become the besieged. With some justification, a newspaper in Paris reported that “the English hold no more than the ruins of Quebec.” This coming winter, it would be British troops who would go hungry and wait to be attacked. Had it really been the battle for a continent? If so, it was not yet over.31

And what of the flaming James Wolfe? His body was onboard the Royal William, bound for England for burial, but what of his reputation? William Pitt himself set the tone in a speech to Parliament that seems to have surpassed even his usual hyperbole. “Carthage may boast of her Hannibal and Rome may decree triumphs of her Scipio,” a newspaper declared, “but true courage never appeared more glorious than in the death of the British Wolfe.”

Later, British Canada would sing, “In days of yore from Britain’s shore, Wolfe the dauntless hero came, and planted firm Britannia’s flag on Canada’s fair domain.” Wolfe would forever be called “the Conqueror of Canada” But did he deserve the name? Christopher Hibbert subtitled his biography, Wolfe at Quebec, “The Man Who Won the French and Indian War.” Taken in that light, Montcalm’s biography might just as readily be subtitled “The Man Who Lost the French and Indian War.”32