If the fall of Quebec and the death of James Wolfe came to dominate a year filled with banner events, there is one more story that must be told before the curtain falls on 1759. Not surprisingly, the story belongs to Major Robert Rogers and his rangers and it begs to be told, if for no other reason, because of its seminal place in American frontier mythology. Whether in James Fenimore Cooper’s nineteenth-century tales or dime novels of the West, a good story has frequently obscured the truth. This occurred all the more in the twentieth century when motion picture images of historical events and personalities became so ingrained in the public psyche that it became difficult, if not impossible, to separate the historic character from the actor. Such is definitely the case with a resolute Spencer Tracy playing the role of Major Robert Roberts in 1940, in the film version of Kenneth Roberts’s classic, Northwest Passage.

The setting for the original drama was as follows. Amherst’s advance down Lake George and his capture of Ticonderoga and Crown Point in midsummer of 1759 had been less a stunning success for British arms than a tactical withdrawal by the French. Neither Fort Carillon nor old Fort Saint Frédéric at Crown Point could have withstood a determined British artillery assault. (Amherst was no Abercromby and doubtless would never have ordered another frontal assault by infantry.) So, under orders from the chevalier de Lévis at Montreal, the French forces on Lake Champlain retired northward to Ile-aux-Noix near its outlet. Having acted quite decisively until this point, Amherst grew cautious. In some respects, he took the bait and spent the remainder of the summer rebuilding these captured posts rather than advancing toward Montreal.

Besides building forts, however, Amherst was faced with two major uncertainties: the maritime control of Lake Champlain and the status of Wolfe’s attack against Quebec. As to the former, the French had a heavily armed schooner and three xebecs (small three-masted ships suited for lake or coastal operations) on the lake. While hardly an armada, this tiny flotilla nonetheless could have caused considerable destruction if turned loose against an advancing convoy of British whaleboats and bateaux. To counter this threat, Amherst had to launch a navy of his own; and as he built forts, his sawmills also constructed a brigantine and a “great radeau or raft, eighty-four feet in length and provided with sails, capable of carrying six twenty-four-pounders.” Once afloat, these vessels would provide cover for any convoy, but their construction also meant more delays in any northward movement.

That left the uncertainty of Quebec. If Wolfe was unsure of what role Amherst might play in operations along the Saint Lawrence, Amherst was equally in the dark about Wolfe. Early in August, the commander in chief dispatched a small party consisting of Captain Quinton Kennedy, Lieutenant Archibald Hamilton, and seven Stockbridge Indians to travel through the country of the Abenaki Indians under the cover of a flag of truce. Ostensibly, Kennedy’s mission was to make peace entreaties to the Abenaki, but in fact he was trying to obtain some word of Wolfe or even to reach Wolfe’s headquarters. This was definitely stretching the use of the white flag, and Kennedy and his party were detained by Abenaki from the village of Saint Francis and turned over to the French as prisoners. When news of their capture finally reached Amherst on September 10, he was furious. Enter Rogers and his rangers.1

Rogers had been out and about from Crown Point on various scouting expeditions. About 200 of his rangers under Captain John Stark had just returned to Crown Point after cutting a road from there through the Green Mountains to the outpost of Number Four on the Connecticut River (present-day Charlestown, New Hampshire). As Rogers remembered it, Amherst, “exasperated at the treatment of Captain Kennedy,” summoned him on September 13 and secretly ordered him to attack the Saint Francis Abenaki in retaliation and “bestow upon them, a signal chastisement.”2

Whatever Amherst’s motives in dispatching Rogers on this assignment, “he could not have assigned a duty more agreeable to the rangers.” The Abenaki had long been the scourge of the New England frontier. If Rogers’s journal is to be believed, some 600 scalps hung from poles at Saint Francis alone. While the rangers were not above similar acts, there was scarcely a man among them who had not had a family member or friend killed or abducted by the Abenaki. The Saint Francis Abenaki professed the Catholic faith, as a result of decades of missionary work by the Jesuits; but far from tempering their actions, this indoctrination made it all the more easy for French priests to suggest that attacks against the English would put them in higher favor with the church. Perhaps their most egregious conduct had occurred in the aftermath of Fort William Henry. To a man, the rangers thought that it was high time for retaliation.3

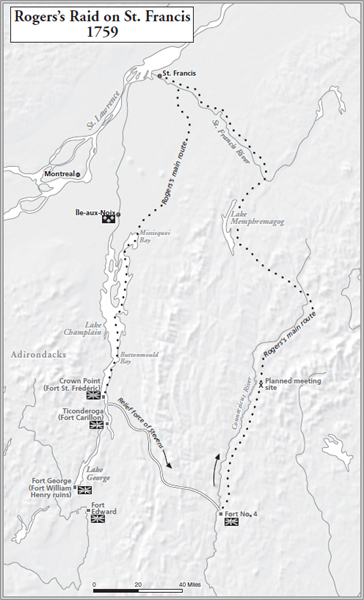

Rogers and some 190 men departed Crown Point in seventeen whaleboats on the evening of September 13, 1759—by coincidence, the day of the great battle at Quebec. Only 132 of this number were true rangers, the remainder being handpicked veterans from the regular light infantry and certain provincial units. Of the rangers, at least twenty-four were Stockbridge Indians and one was a twenty-six-year-old black man, “Duke” Jacobs, who had been granted his freedom after three years with the rangers, but who nonetheless volunteered for the Saint Francis raid.4

Dawn the next morning found the force holed up at Buttonmould Bay on the eastern shore of Lake Champlain. On their second night out, Rogers and his men reached the mouth of Otter Creek where they were forced to wait until patrolling French vessels moved farther up the lake toward Crown Point. Finally, ten days after leaving Crown Point, the little flotilla arrived at Missisquoi Bay in the northeast corner of Lake Champlain. Here, Rogers hid his boats, and with 149 men—the remainder had already started back to Crown Point with various maladies—set off cross-country for Saint Francis (near modern-day Pierreville, Quebec), about seventy-five miles away as the crow flies.

Two problems quickly presented themselves. First, the men were not flying, but slogging through an interminable spruce bog covered with water a foot deep. Such terrain added immeasurably to the distance, not to mention the discomfort. Second, on the second day in this quagmire, the two Stockbridge Indians who had been left to watch the whaleboats caught up with the main body and reported that the French not only had discovered and burned these boats but also were in pursuit with some 300 men. Barely into the raid, the rangers’ presence was known and their planned avenue of escape closed.

Rogers now leaned on his knowledge of the New Hampshire frontier. He sent Lieutenant Andrew McMullen and six others back to Crown Point with a report to Amherst that he intended to make a wide loop eastward and return by way of Lake Memphremagog and the Connecticut River and that Amherst should hurry provisions north from Number Four to meet him. As for their objective, “We now determined to out-march our pursuers,” Rogers wrote later, “and destroy Saint Francis, before we were overtaken.”5

In some respects, the spruce bog became their ally, making any pursuit as tortured as their own advance. Today, when we are used to Gore-tex and weatherproof boots, it is difficult to imagine being wet in wool clothing and leather moccasins for days on end. At night the rangers hacked spruce boughs off trees and stuffed them into the lower branches to make fragile but welcome hammocks above the morass. Food was already a problem.

For ten days they struggled through the swamps and then on the evening of October 2 emerged on the west bank of the Saint Francis River about twelve miles above the village. As it lay on the opposite shore, the rangers were forced to cross the five-foot-deep Saint Francis the next day by linking arms together in a human chain. By that evening, they were hidden in the woods surrounding the village. Half an hour before sunrise on October 4, 1759, Rogers and 142 of his men rushed forward to attack.

The village of Saint Francis consisted of over “sixty well-built, framed and windowed houses covered with bark, boards and even stone.” The two principal buildings were the Jesuit mission church and the council house that had been the scene of a wedding feast the night before. Rogers estimated the population killed in the next hour at 200, but that number is highly suspect. Many of the warriors were not in town, having left previously to await Rogers’s emergence from the spruce bog at Yamaska to the west. Others fled and hid with women and children in a little ravine just east of the town. Still others hid in their homes and probably did perish as Rogers’s men torched every building in town except three granaries of corn. Rogers took twenty women and children prisoners, and some others were undoubtedly killed in the fires despite Amherst’s instructions that “no women or children should be killed.” One French estimate gave the number of casualties at Saint Francis as ten men and twenty women and children.6

As smoke from the burning buildings filled the autumn morning, many rangers hurriedly scooped up corn and provisions. Others gathered plunder, including, it has long been alleged, numerous icons from the mission. These would become part of a subset of the legend of this raid—the lost “treasure” of Saint Francis. In the grim weeks ahead, most rangers would have gladly traded anything for the corn.

And then, within minutes, it was time to go. Soon, parties of French and Abenaki from Montreal to Three Rivers would be in pursuit. They included sixty regulars and militia under the command of Major Jean-Daniel Dumas, the officer who, as a young lieutenant in 1755, had steadied the French line and halted Gage’s advance guard on the Monongahela. Now, there was clearly no escape for the rangers except up the Saint Francis and down the Connecticut.

For eight days, Rogers led his men up the east bank of the Saint Francis River, averaging about nine miles a day. Then, at the fork of the Magog River (present-day Sherbrooke, Quebec), as the rations of corn from Saint Francis gave out, an officers’ council prevailed on Rogers to divide the command into smaller groups in the hope of finding game. Rogers had hoped to keep the party intact for at least another thirty or so miles to the southern end of Lake Memphremagog and the divide between the Saint Lawrence and Connecticut watersheds. But on the morning of October 12, he reluctantly agreed to follow his own ranger rules for dispersal and divide into eleven parties.

Three groups determined to strike southwest directly toward Crown Point, while the others agreed to rendezvous on the Connecticut River about sixty miles above Number Four, near where Rogers had proposed the construction of Fort Wentworth in 1755. Here, they hoped to find the supplies Amherst had dispatched from Number Four.7

In his request to Amherst sent via Lieutenant McMullen, Rogers had asked that Lieutenant Samuel Stevens be placed in charge of the relief column because of his knowledge of the upper Connecticut. Stevens had in fact commanded a platoon of rangers at Number Four during the winter of 1758–1759. On the same day as the attack on Saint Francis, Amherst ordered Stevens to gather supplies and men at Number Four, march north to the mouth of the Wells River, and remain there “as long as you shall think there is any probability of Major Rogers returning that way.” The question that would haunt Stevens’s subsequent court-martial—and the question that is still being asked today among aficionados of Rogers’ Rangers—is this. Given Rogers’s already legendary record of survival, how long a wait was enough?8

Stevens’s timing was uncannily close. His relief party of five men from Number Four paddled a large canoe laden with supplies up the Connecticut, portaging several falls, and arrived within five miles of the Wells-Ammonoosuc-Connecticut confluence on October 19. Here, they halted because of strong rapids, but Stevens and others “went daily by land to Wells River and fired their muskets to signal Rogers.” But for how many days? Maybe only one.

Rogers reached the appointed rendezvous on October 20. His party numbered twenty-six others. Both Rogers and Stevens reported hearing musket shots. Stevens discovered two hunters, determined them to be the cause, and shortly thereafter paddled back down the Connecticut with the supplies. Rogers discovered Stevens’s fire, still smoldering, at Wells River and collapsed in despair.9

For Rogers’s partisans to this day, Stevens remains the villain, never to be forgiven. Rogers summoned his strength and with three others made an epic descent of the Connecticut by raft to Number Four. Within half an hour of his arrival, supplies were hastened back upriver to the forks, but by one count thirty-four men in the groups that finally reached there died of starvation before help arrived. Other returning parties ended up scattering as far east as Lake Winnipesaukee, and one managed to reach Crown Point directly. Rogers himself rested at Number Four only one day and then returned upriver with two more canoes of provisions.

Rogers was more than bitter. He pushed for Stevens’s court-martial the following spring, and the lieutenant was found guilty of neglect of duty and relieved of his command. Stevens had arrived back at Crown Point on October 30, saying that it was most unlikely “that Rogers would return by way of Number Four.” Amherst himself expressed some skepticism and recorded in his journal that Stevens should have waited longer. Eight days later, Captain Amos Ogden, who had rafted down the Connecticut with Rogers, walked wearily into Crown Point with Rogers’s report to prove the contention.

If Stevens has any supporters, they remain cowed by the insurmountable legend of Rogers and his rangers. It might only be said in Stevens’s defense that waiting with only five others—townsmen no doubt eager to return to Number Four—along the route of known Abenaki incursions into New Hampshire must have given Stevens pause. But why didn’t he at least cache provisions at his northernmost point? The answer is that he had explicit orders not to do so. Amherst’s direct orders were that after waiting at his own discretion, Stevens was to “return with said provisions and party to Number Four.” Likewise, Amherst’s orders to the commissary at Number Four indicated that if Stevens did not encounter Rogers, he would “return with said provisions to you, and you will return them into the King’s stores.” Even if Stevens had considered doing otherwise, he was no doubt swayed by his belief—as he testified at his court-martial—that if he was going to meet Rogers at all, it would have been earlier at Number Four.10

By the best estimates, Rogers lost 69 of the 142 men who left Missisquoi Bay with him. One was killed in the attack on Saint Francis; seventeen died in various ambushes on the return; forty-three succumbed to starvation; and the fate of eight is unknown. Even compared with the most horrendous encounters of the period, this casualty rate was appalling. There is some evidence that both Rogers and General Amherst sought to sweep the figures under the table or at the very least not tally them all in one place.11

But it hardly mattered. In many respects, the numerous deaths and the hardships of the retreat only heightened this exploit in the public mind. Contemporary colonial newspapers continued to sing the praises of “the famous Rogers.” Rogers himself published his journal and various other accounts after the war, partly to obscure less heroic ventures, as shall be seen some pages hence.

But no one remembered that. Instead, tales of the rangers’ campsites, buried treasure, elusive escape routes, and escapades real or imagined permeate upstate Vermont and New Hampshire. Indeed, local stories that “Rogers’ Rangers passed through here” became almost as ubiquitous as signs saying “George Washington slept here.” By the time Spencer Tracy marched his way across the silver screen in 1940, the legend of Robert Rogers and his rangers was forever intact.