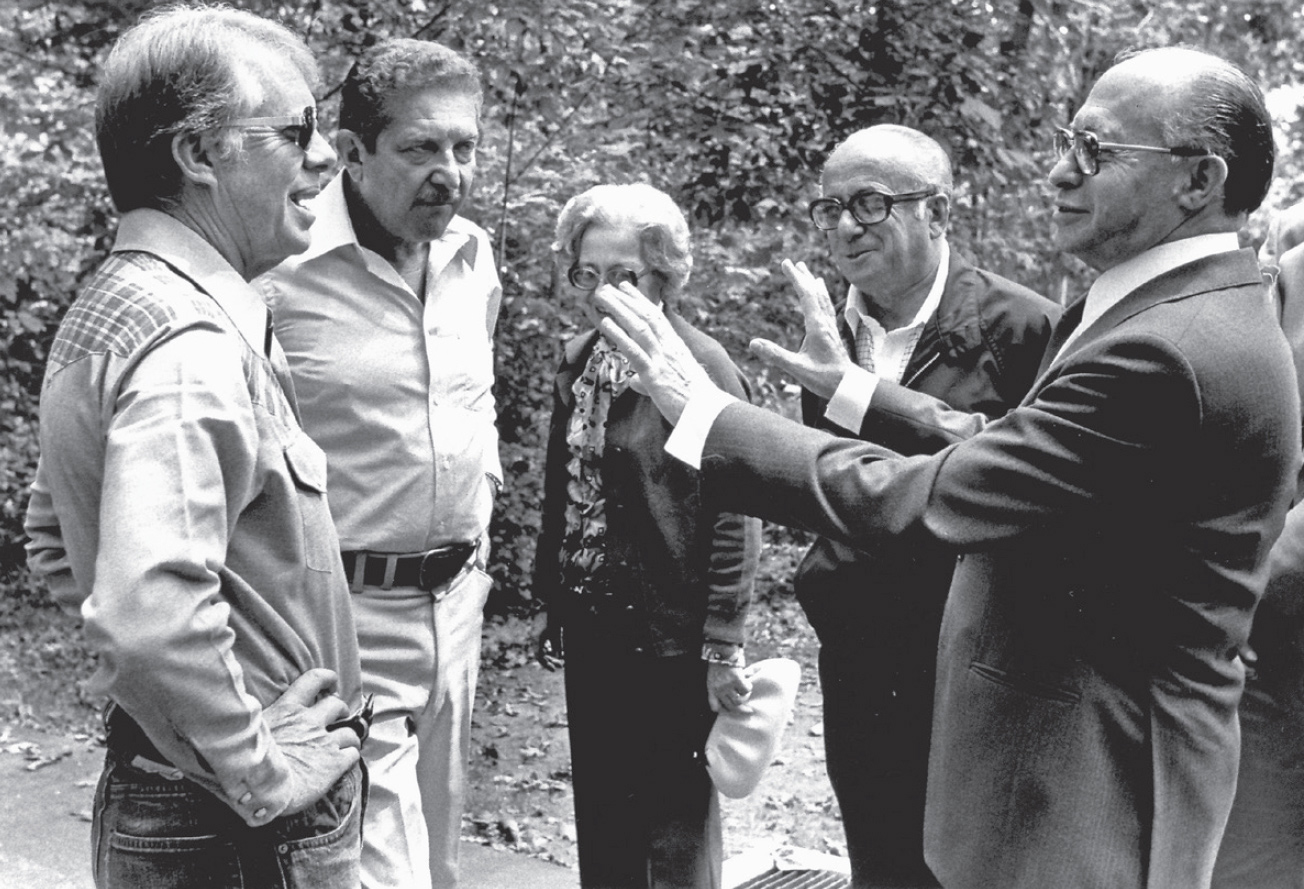

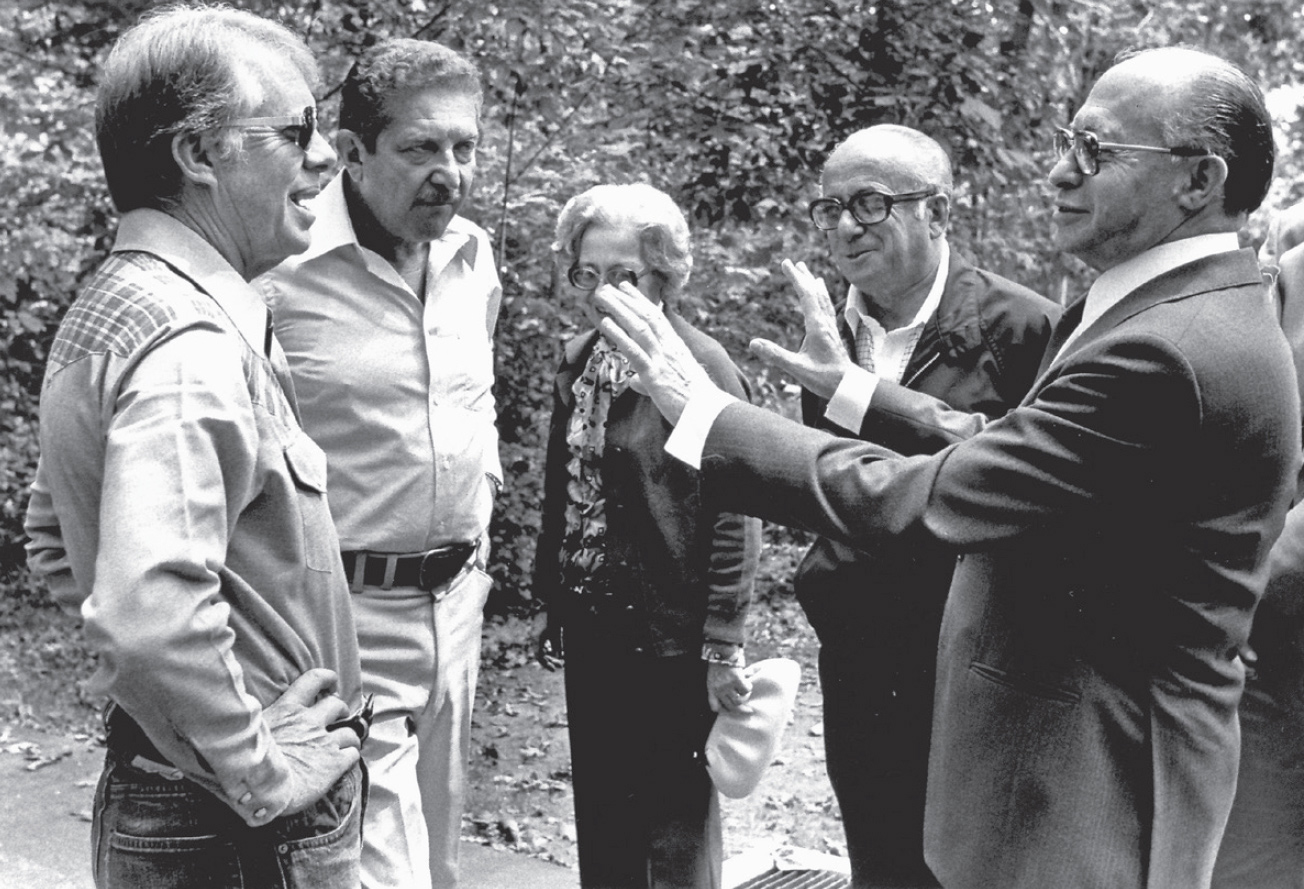

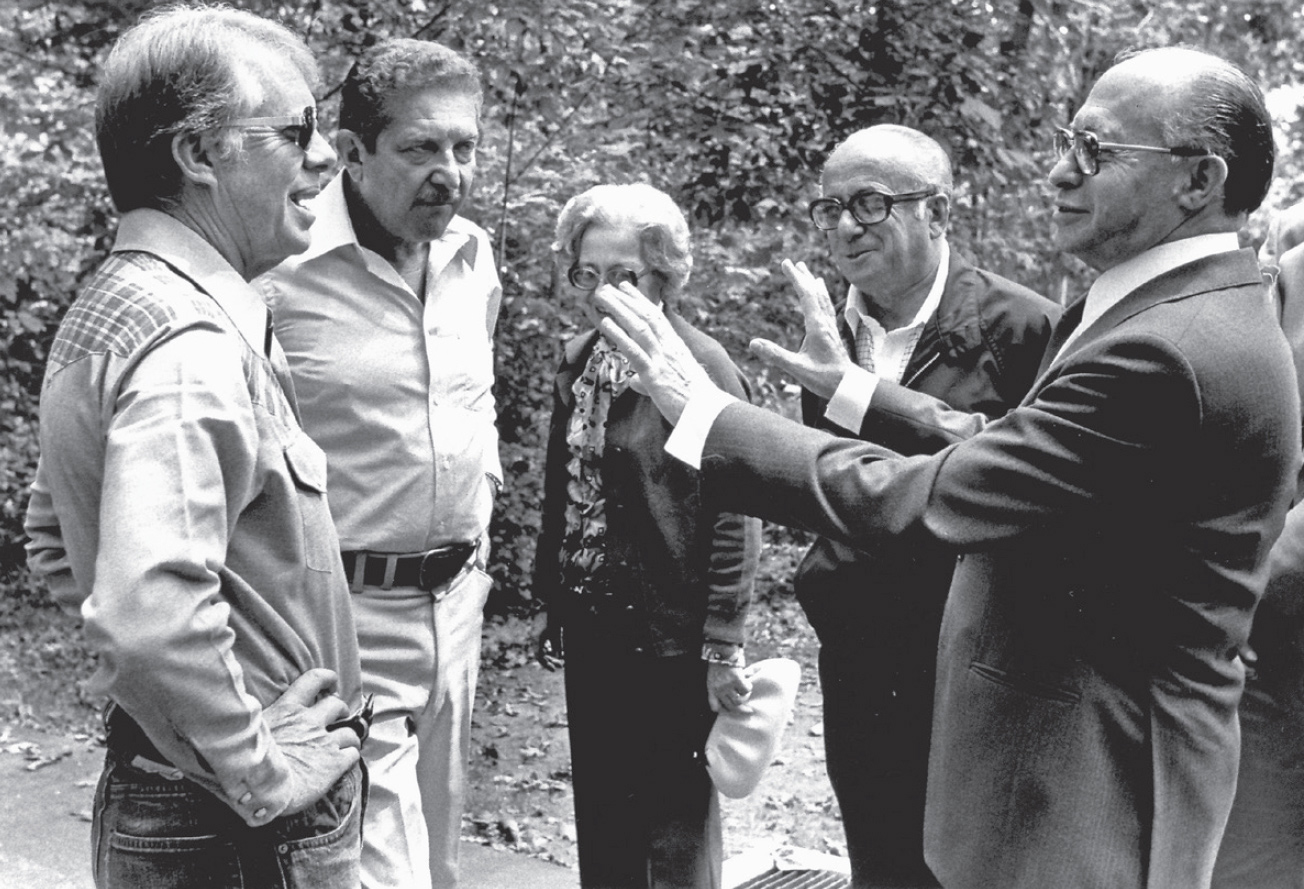

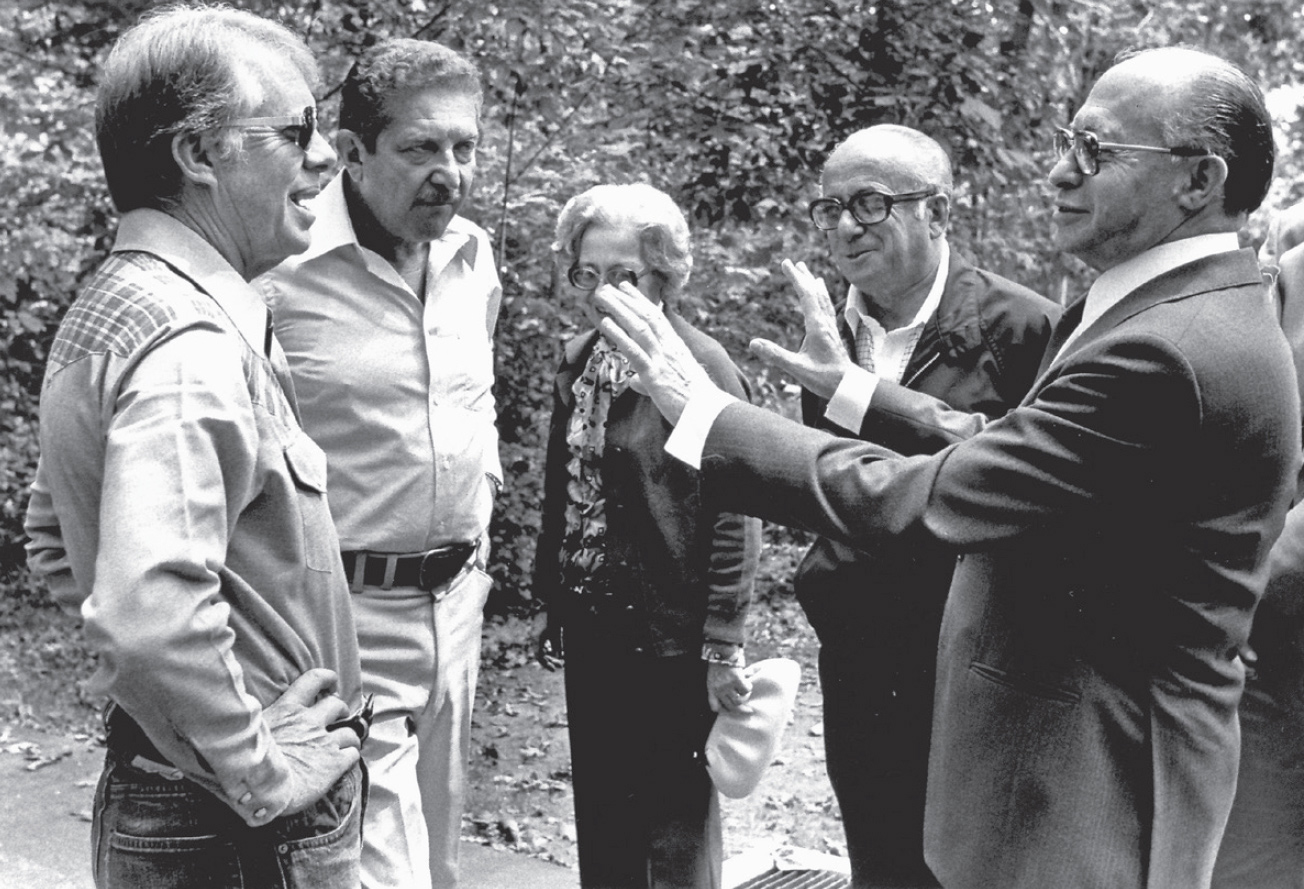

Jimmy Carter, Ezer Weizman, Aliza Begin, Yechiel Kadishai, and Menachem Begin at Camp David

Jimmy Carter, Ezer Weizman, Aliza Begin, Yechiel Kadishai, and Menachem Begin at Camp David

SINCE HIS NAVY DAYS, Carter had awakened each morning at five, a habit he could never break no matter what time he got to bed. This morning he looked over his dictation, and when the sun came up he and Rosalynn played tennis for about an hour. Cy Vance and Zbig Brzezinski joined them for breakfast. Carter kept shaking his head as he described his meeting with the Israeli prime minister the night before. Begin had seemed rigid and unimaginative, parsing every syllable; he was entrenched in the past and unwilling to look at the broad perspective. Carter was already dreading the meeting that afternoon among the three leaders.

Sadat rose at eight, went for his vigorous daily walk, then met with Carter at ten a.m. “My program is ready,” Sadat proudly told the president, handing him a draft of the Egyptian position. As Carter read “The Framework for a Comprehensive Peaceful Settlement of the Middle East Problem,” his heart sank. It was certainly comprehensive—page after page of uncompromising Arab boilerplate that was bound to torpedo any possibility of an accord; for instance, Sadat was insisting that Israel sign the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, to which Egypt had acceded but Israel had not. All settlements in the occupied territories would be dismantled. In addition to totally withdrawing from Sinai, Israel would have to pay for the oil it had pumped and the damage caused by acts of war to people and civilian installations. Displaced Palestinians would be allowed to return to Israel or receive compensation, and within five years there would be a Palestinian state on the West Bank. Israel would surrender control of East Jerusalem to Arab sovereignty. It was a fantasy. There was almost nothing Israel could agree to.

Sadat said he intended to read aloud the “Framework for Peace” at the afternoon meeting. Imagining Begin’s reaction, Carter warned Sadat that it would be a terrible mistake, but it was clear that Sadat wanted a strong initial position that would appease other Arab leaders and make it easier for him to grant concessions in the long run. Then he made a surprising offer. This part of the discussion was to be kept totally secret, Sadat stressed. He produced three typewritten sheets of paper, marked for the president’s eyes only, in which he proposed several concessions that Carter could use at his discretion. Sadat would agree to full diplomatic relations, with an exchange of ambassadors and free movement of peoples across the border, routine postal service, free trade—a normal, neighborly relationship, in other words, which was exactly the future that Carter hoped to secure. In addition, there could be a more modest approach to the Palestinian refugees, as well as the establishment of a self-governing authority in the West Bank short of a state. Sadat would also agree to minor modifications in the borders of the West Bank to accommodate Israel’s security needs. In Sinai, he would accept the presence of UN peacekeepers. Jerusalem could remain an undivided city. These were all points that Carter thought he could sell to Begin. For the first time Carter caught a glimpse of a possible settlement. But for now, he was the only one who knew of the existence of this secret memorandum. Sadat had even kept his own delegation in the dark.

WHEN SADAT RETURNED to his cabin, he was in high spirits, his foreign minister observed. Mohamed Kamel had known Sadat for most of his adult life, even before they were in prison together. They had been drawn together because of their lifelong hatred of the British, which united them in a sensational conspiracy.

In the summer of 1942, the German tank corps of General Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox,” had bottled up the British Eighth Army in El Alamein, a seacoast town in northern Egypt. Many fervent Egyptian nationalists thrilled to the Nazi invasion and openly prayed for Britain’s defeat. “Germany is the enemy of our enemy, England,” Sadat later explained. Sensing an opportunity to make history, he took it on himself to send a letter to Rommel, proposing that elements in the Egyptian Army would block British soldiers from leaving Cairo so that German forces could have a free hand; in return, Egypt would be granted her complete independence. At the time, Sadat was a twenty-three-year-old captain in the Signal Corps, but he felt entitled to negotiate a treaty between Egypt and one of the most illustrious figures in military history. The letter never actually got to Rommel; Sadat had dispatched a fellow conspirator to fly to El Alamein and deliver the note, but he flew in a British plane and the Germans shot it down.

Soon after that, two Nazi spies contacted Sadat. Their names were Johannes Eppler, who was half Egyptian, and Hans-Gerd “Sandy” Sandstede. They had a damaged transmitter that they hoped Sadat could repair. Sadat saw another chance to communicate his scheme to Rommel, and he readily agreed. The spies were living it up on a houseboat on the Nile belonging to a well-known belly dancer. They boasted to Sadat that a Jewish intermediary had changed more than forty thousand counterfeit British pounds for them. “I was not surprised that a Jew would perform this service for the Nazis because I knew that a Jew would do anything if the price was right,” Sadat recalled. “But I was worried on behalf of Eppler and Sandy over this contact with the Jews.”

Hekmet Fahmy, the belly dancer, had the face of an ingénue, but she was a fierce Egyptian nationalist, the Mata Hari of Cairo. Eppler used her to lure British officers she met at the Kit Kat Cabaret to the houseboat. While she was occupying the officer in her bedroom, the spies would go through his papers. Sadat began spending nights at the houseboat himself, where the scene became one of mounting depravity. Eppler was obsessed with the legend of “A Thousand and One Nights,” and he was constantly playing a recording of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. He told Sadat, “How happy King Shahryar must have been—getting a fresh virgin every night and then killing her in the morning! That’s my ideal life!”

The Nazi spies were caught, and they quickly implicated Sadat. Eppler complained that they had been betrayed by two Jewish prostitutes, who turned them in to British authorities after he had threatened to “slaughter” them during a role playing of “A Thousand and One Nights” while singing “Deutschland über Alles.”

Sadat was arrested in September 1942. Two years later, when the war was clearly coming to a close, many Egyptian prisoners who had fallen afoul of the British were freed, but Sadat was not. As a kind of publicity stunt, he and several companions escaped from the lightly guarded prison where they were held, hailed a taxi to the king’s Cairo residence, Abdeen Palace, signed the guest book, and then took a cab back to the prison. After this escapade, Sadat went on a hunger strike, and when he was eventually sent to the hospital, he slipped away once more. For the next year, he lived as a fugitive. He grew a beard to disguise himself and tried to find work as a contractor. Sadat was free but destitute. In 1945, his ten-month-old daughter died, apparently of starvation.

It was during this period that he met Mohamed Kamel. Kamel was the leader of an underground organization that stalked and killed British soldiers, usually when they were drunk and alone on the streets of Cairo. The two men met in a coffee shop in Opera Square. Sadat was a striking figure, tall, quite dark, with a mustache and a deep, resonant voice. In Kamel’s opinion, Sadat wore “eccentric clothes”—a dark gray suit, a red-checked waistcoat, and an especially notable pair of white leather shoes, quite an outfit for a man on the run.

Sadat immediately understood how he could employ Kamel’s little “murder society,” as he called it. Shooting a handful of British soldiers was not going to liberate Egypt, but it could be a sort of “limbering up” for the main task: eliminating prominent Egyptians who supported the British—in particular, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Nahhas.

Sadat took the aspiring assassins into the desert, taught them how to shoot, and schooled them in the use of hand grenades. The plan was to hurl the bombs at the prime minister’s car as it passed by the American University in Cairo on Qasr el-Aini Street and then riddle him with bullets for good measure. Sadat gave Kamel and the other killers a package containing the grenades and a couple of pistols, and then he waited in the getaway car in front of the university. When Nahhas’s car appeared, it suddenly sped up to avoid a tram, and the grenade exploded behind the target. The conspirators scattered. The getaway car was nowhere to be seen.

Sadat quickly produced another candidate for elimination: Amin Osman, a minister in the government who had said that the relationship between Egypt and its British occupiers was “as unbreakable as a Catholic marriage.” This time the attempt was successful. Osman was shot as he was entering the Old Victorians’ Club, a favored den of the English and a highly symbolic venue for the assassination. “Apart from removing a staunch supporter of colonialism, we had seriously damaged the prestige of the British authorities,” Sadat boasted. Within a few days, however, the killer made a confession and the entire murder society was rounded up and jailed.

Kamel came from a wealthy and influential family; in fact, his father was a prominent judge, which meant that he was granted special favors. His family sent food into the prison, which Kamel generously divided among his codefendants. Sadat loved Kamel’s mother’s cooking and would boldly request special dishes, such as rice-and-pigeon casserole. Kamel was also allowed out of the prison twice a week, allegedly to go to the dentist. There he would meet his family and some of Sadat’s military friends, who would fill Kamel’s pockets with goods to be smuggled into the prison.

The trial of what was called “the great political assassinations case” filled the front pages of Egyptian newspapers during the two years that it took place. Sadat’s involvement was the main subject of interest; the former military officer was already well known for his attempts to collaborate with the Nazis. His bravado and lurid background, with his handsome looks and natural dramatic flair, made him a tabloid sensation and a hero to Egyptian nationalists. “Condemn me to death if you like,” he declared from the cage that enclosed the defendants in the courtroom, “but stop the public prosecutor from praising British imperialism in the venerable presence of this Egyptian court of law.”

Although he doesn’t write about it in his memoirs, Sadat was twice smuggled out of prison by a group of young military officers who were dedicated to protecting the honor of the king from British humiliation. They called themselves the Iron Guard. Like Sadat, they too hoped to assassinate Mustafa al-Nahhas. Sadat was in a car belonging to the royal palace when shots were fired at the prime minister, but missed. A month later, Sadat was involved in a car bombing of the minister’s house, but he was never charged. (The charmed Nahhas lived to be a very old man.)

Sadat and Kamel adamantly lied about their involvement in the political assassinations case and were eventually acquitted. “My efforts at the cross-examination had adequately thrown the case into confusion,” Sadat happily concluded. Soon he was able to return to the military, where he joined the conspiracy that Nasser had established to overthrow the king. Kamel went into the Foreign Service, eventually becoming the Egyptian ambassador to West Germany. The two men rarely saw each other in the intervening years, even as they ascended in their government careers.

In December 1977, when Kamel had returned to Cairo for official business, his wife heard on the radio that he had been appointed foreign minister. He was shocked; Sadat had not even bothered to tell him. By making a public announcement, Sadat made it impossible for Kamel to back out without creating a scandal. Two foreign ministers in a row had already resigned because of Sadat’s peace overtures. Kamel felt trapped; old ties of loyalty going back to their prison days pulled on him, but in truth he was appalled by any dealings with the Israelis. He believed that once you began to talk, half the battle was lost, because dialogue implied equality. Egypt was too weak to be Israel’s equal. The only strength Egypt had was to stand with other Arabs in their refusal to negotiate. Sadat was deaf to his concerns, however. “Do you remember when we were in prison?” Sadat asked him when they finally did talk about the job. “You’ll have a place in history with me, Mohamed!”

Kamel arrived at Camp David in a state of great emotional distress, smoking too much, far more worried about success than failure. After some of the previous meetings with Israelis, Kamel had been heard sobbing in his room. Vance had tried to pacify him. The Israelis’ historic claim to Arab lands caused him to explode with outrage: “The Israeli attitude rests on an erroneous racist belief, which dominates their thinking and governs their behavior—namely, that they are God’s Chosen People. Accordingly, whatever they believe, their rights transcend the rights of others.”

AFTER RELATING HIS MEETING with Carter that morning, Sadat suggested to Kamel and other members of his delegation that they take a walk in order to get familiar with the surroundings. Sadat set off in his tracksuit. Along the way they ran into Menachem Begin in a golf cart. It was the first tentative encounter between the two men at the camp.

“How are you, Mr. President,” Begin said, as they shook hands. “You are looking well. I hope you are feeling well, too.”

“You are looking well, too, Mr. Prime Minister,” Sadat replied, sizing up his adversary.

Their health was a subject of constant speculation and scrutiny by all parties. Both men had suffered repeated heart attacks. Of the two, Sadat seemed to be in better condition, although he handled his health like a cracked pot that had to be very carefully used. He usually slept until nine or nine thirty in the morning; upon waking, he ate a spoonful of honey and royal jelly, along with a cup of sweet mint tea. He prayed, bathed, and shaved, then went back to bed to read the papers until breakfast—usually yogurt or papaya and honey. Eventually, he dressed for work, fortified perhaps with a shot or two of vodka as a tonic to stimulate his heart. For the next three or four hours he conducted official business, receiving visitors and reading reports. He believed he got colds very easily and so he forbade air conditioning no matter what the temperature. Whenever needed, an aide supplied a clean white handkerchief to mop the perspiration from his face. For an hour each afternoon, he lay on the floor of his bedroom with a scarf over his eyes. As part of his diet, he had given up eating lunch, although he still smoked a pipe, which was rarely out of his hand. Every day, he would take his vigorous two-and-a-half-mile walk. The only other exercise he allowed himself was Ping-Pong; in addition to his other duties, he was chairman of the African Union for Table Tennis. Exercise was followed by a massage, a bath, and a long nap. He would wake again around seven in the evening. He had another glass of tea, then a light supper. He conducted more business until nine, when he put on his pajamas and sent out a list of films he wanted to watch—mainly American westerns—which he enjoyed with a nightcap of whisky.

Begin seemed to have an aversion to exercise, although unlike Sadat he had managed to give up smoking. He took a number of medications for heart disease and diabetes, which drained his vitality and undermined his mood. He, too, ate a bland diet, preferring boiled chicken and cottage cheese, but he drank tea constantly—in the Russian style, with a cube of sugar in his mouth. He was frequently withdrawn and depressed. In 1951, after one of his many failed elections, he briefly retired from politics and sailed to Italy with Aliza. It was rumored among his staff that he had spent time in a Swiss sanatorium during that period. Throughout his life he would plunge into dark moods, and even in cabinet meetings he was often listless and unable to concentrate.

Anwar Sadat

There was concern among the Americans that the stress of the negotiations at Camp David could be perilous for both men. Mortality was an unacknowledged guest but always present.

CARTER ASKED BEGIN to come to the three o’clock meeting a little early, and when he arrived Carter appeared extremely nervous. “President Sadat brought a written proposal with him,” Carter said, warning Begin in advance that he knew the Israelis would not be willing to accept it. “But I would not want that to break up the conference.”

Sadat arrived, now showered and dressed, like Begin, in a coat and tie—neither man was willing to adopt Carter’s insistent informality. They sat on the porch of Aspen, around a small wooden table in the mottled afternoon light. Carter intended to participate as little as possible in this meeting, hoping that the two men would get to know each other better and begin to trust one another. At that point, he still saw his role as a facilitator, nothing more.

Begin started by saying, “We must turn over a new leaf.” But he added, “Negotiations require patience.”

“It’s true we need time,” Sadat agreed. He wanted a framework for comprehensive settlement, details to be sorted out later by the drafters of the treaty. “I think we will need three months’ work.” Sadat seemed uncharacteristically ill at ease, fumbling over his words several times as he responded. The tension of the first meeting was affecting each of them.

Begin noted that when the Catholics choose a new pope they say, “Habemus papam.” He hoped that at the end of the conference the three of them would all be able to say, “Habemus pacem”—we have peace.

After these pleasantries, the moment that Carter had been dreading arrived. Sadat put on his glasses and read from his eleven-page plan. “Further to the historic initiative of President Sadat,” he said immodestly, “the initiative that revived the hope of the entire world for a happier future for mankind, and in consideration of the desire of the Middle Eastern peoples and all peace-loving peoples to end the pain of the past …” He went on in this high-flown vein until he came to the actual proposal. For the next ninety minutes, he read feelingly, gripping the sides of his chair at times as he made his demands for a Palestinian state, an Arab stake in Jerusalem, the return of Sinai, the elimination of all settlements, and Israel’s withdrawal to the 1967 lines. Begin sat stony-faced. Carter sensed the lava rising in the volcanic prime minister. When Sadat finally concluded his presentation, there was a moment of complete silence.

Carter broke the tension by suggesting to Begin that he could save everyone a lot of trouble if he just signed the document as written. Suddenly, all three leaders burst into laughter. Begin made a surprisingly polite response, saying that he appreciated how hard the Egyptians had worked on their document, but now he would have to read it more carefully and consult with his aides. The three leaders agreed to meet again the following day. Everyone parted in high spirits.

It was odd. Carter had predicted to Rosalynn, “Begin will blow up,” but on the contrary, he appeared strangely relieved. So did Sadat.

BEGIN’S MEETING with his advisers on his porch at Camp David became a nightly ritual. His assistant, Yechiel Kadishai, would solemnly draw a chair to the center for Begin, “like a rabbi,” Dayan observed. On this chilly autumn evening, as Begin recounted the session with Sadat and Carter, the Israelis were aghast. Begin noted that Sadat had even demanded compensation—as if Israel were the defeated nation, not Egypt. “What chutzpah! What impertinence!” he railed.

“Chutzpah is an understatement,” Dayan agreed.

Begin added a bit of uncharacteristic Israeli slang: “If I’m wrong about the Egyptian document, I’m a flowerpot!”

It was clear in Begin’s tirade that he felt that Sadat’s opening gambit breached the normal boundaries of diplomacy, and that somehow Israel’s national honor had been called into question. He was acutely sensitive to such slights. His life and career testify to his ceaseless effort to promote Jewish dignity—the word he used was hadar, which actually means glory or splendor, in any case the extreme opposite of the degradation and victimization that Jews had experienced in modern history. His attempt to embody this quality accounted not only for his grandiose manners and love of ceremony but also for his absence of sympathy for cultures that were not Jewish. Such flintiness made him a daunting figure in the underground but a difficult man to reason with at a peace conference. “There is only one thing to which I’m sensitive,” he admitted to Carter. “Jewish blood.”

THE ISRAELIS REALIZED that there was a relationship between Begin and Kadishai that could not be understood in the usual terms of employment or friendship. It had begun in Tel Aviv in the early days of the Second World War. Kadishai was part of a group of Jews who had joined the British Army. About twenty of them would meet secretly in a cellar under King George Street, trading rumors about what was happening in Europe. They all had families there, and word was spreading that the Germans were massacring Jews. Was it true? What could they do? They had so little information.

One day, the door to the cellar opened and a slender young man—the others at first thought he was a boy—entered. He was wearing round glasses and an army uniform with a Scottish cap and knee shorts with buttons on his socks. On his cap was the emblem of the Polish eagle, signifying his membership in the Anders’ Army, made up of former prisoners who had come out of the Russian gulags. After the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin had released the Polish prisoners, including Jews, and allowed them to form their own army under General Wladyslaw Anders. Eventually, the Anders’ Army came under the British High Command in the Middle East.

The young man brought appalling news to Kadishai and the Jewish soldiers gathered in the cellar in Tel Aviv. The Jews in Poland—more than three million—were already condemned, the mysterious messenger said. But the Jews in Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria could be rescued because the Germans had not yet turned their attention to them. “We can save them, but there are no savers,” he said. If Great Britain would only open the doors to Palestine, Jews from all over Europe would come pouring in—on bicycles, trucks, they would even walk through Turkey and Persia. But the only way to persuade the British was to cause trouble.

Kadishai—who was nineteen at the time—turned to one of his military comrades. “Who is this boy?” he asked. One of the soldiers replied, “He came now from Siberia. His name is Menachem Begin.”

Soon after that, Kadishai signed up to become one of Begin’s troublemakers. In 1946, during the Irgun campaign to drive the British Mandate out of Palestine, Kadishai would help blow up the British embassy in Rome. Three decades later, Kadishai was still at Begin’s side, attending him with a kind of spousal tenderness that no one questioned or entirely understood. Only those who had been with Begin in the underground grasped the moral cost of his journey, and no one knew better than Kadishai. But who could ever have imagined that it would bring them to this wooded mountain retreat to talk about peace?

IN DECEMBER 1943, when he was thirty years old, Begin became the head of Irgun. The idea of waging a Jewish insurgency at a time when the British were fighting the Nazis seemed like madness to many Jews. However, the British, freshly awakened to the value of oil and hoping to maintain productive relations with Arab countries, agreed to severely restrict Jewish immigration into Palestine. The Irgun was smuggling Jews out of Europe, but British authorities were blocking ships carrying refugees to Palestine and sending them back to the European slaughterhouse.

The organization that Begin took over was nearly defunct; there were about a thousand members in Irgun at the time but only a third of them were trained fighters; between them they had one machine gun, five submachine guns, a number of pistols and rifles, along with a hundred hand grenades and five tons of explosives. With that meager inventory, Begin declared an armed rebellion against the British Mandate. “We shall fight, every Jew in the homeland will fight,” he proclaimed. “There will be no retreat. Freedom—or death.”

Begin intuitively understood that terror is theater. Murder was not the object, even if it was the inevitable result. His idea was to create a number of showy attacks that would make headlines in London and New York and provoke repressive countermeasures. Predictably, British authorities would resort to mass internments, brutal interrogations, and exemplary executions; the Jews of Palestine would be increasingly alienated and aroused; and Britain’s standing in the world community would suffer, as would support for the Mandate in Britain itself. “History and our observation persuaded us that if we could succeed in destroying the government’s prestige in Eretz Israel, the removal of its rule would follow automatically,” Begin writes.

Thenceforward, we gave no peace to this weak spot. Through all the years of our uprising, we hit at the British Government’s prestige, deliberately, tirelessly, unceasingly.

The very existence of an underground, which oppression, hangings, torture and deportations, fail to crush or to weaken must, in the end, undermine the prestige of a colonial regime that lives by the legend of its omnipotence. Every attack which it fails to prevent is a blow at its standing. Even if the attack does not succeed, it makes a dent in that prestige, and that dent widens into a crack which is extended with every succeeding crack.

Begin’s brilliant improvisations created a terrorist playbook that would be followed by groups around the world—including Palestinian organizations—that hoped to emulate his success.

Begin was fortunate in that he was dealing with a weakened and distracted adversary that was still enmeshed in a war with Germany. During its entire history in Palestine, Britain never formulated a coherent policy in fighting Jewish terrorism, which unlike Arab revolt a decade earlier took place largely in the cities, where it was easy for the insurgents to fold back into the surrounding communities. Begin’s goal was not to win battles but to prove to the British that Palestine was ungovernable. He concentrated on highly symbolic targets, starting with simultaneous attacks on three British immigration offices, which were in charge of blocking illegal Jewish immigrants. That was followed by similar attacks on four police stations. He raised money through extortion and theft. In January 1945, Irgunists snatched a shipment of diamonds from a post-office wagon in Tel Aviv, which they later sold for forty thousand British pounds. A year later, they stole a similar amount in cash during a train robbery. Weapons were obtained from raids on British arsenals and eventually supplemented by Irgun’s own weapons factories. In July 1945, the British placed a reward of two thousand Palestinian pounds on his head. Begin went into hiding. He grew a beard and disguised himself as a Hassidic rabbi named Israel Sassover, with a long black coat and a narrow-rimmed hat. He lived with his family in a small apartment in Tel Aviv, where the terrorism impresario spent much of his time changing diapers and washing dishes. Except for his daily newspaper delivery and his prayers in the synagogue, few other people ever saw him during this period.

One who did meet him was Moshe Dayan, who was by then a trusted officer in Haganah, the Jewish defense organization. Relations between Haganah and Irgun were always fraught. Haganah was working at the direction of the official Jewish Agency, then headed by David Ben-Gurion. Almost from the moment Begin entered Palestine, Ben-Gurion saw him as a rival. Haganah had a history of accommodation with British authorities, which Begin infuriatingly compared to the diffidence of the European Jews during the rise of Nazism. Ben-Gurion had vowed to shut down Irgun at any cost, and he sent his protégé Dayan to deliver a message.

Begin was dazzled by the dashing young officer, his contemporary but his opposite in so many ways. Dayan was a native-born Israeli—a sabra—who embodied the Fighting Jew that Begin had summoned in his imagination. “He had lost his eye in Syria, but he certainly had not lost his courage,” Begin observed admiringly. Begin, on the other hand, still had the refined air of a Polish lawyer. Dayan noted that, although Begin was in hiding, he still managed to present a neat appearance. “He has large and parted front teeth and is well dressed,” Dayan reported. The message that Dayan came to deliver was that Irgun should stay in line. “You have no right to act without coordination and approval,” he said. This was not the time for a freelance insurgency. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had promised to allow Haganah to form a brigade to fight the Nazis, which Ben-Gurion hoped would form the basis of a future Jewish army. Begin replied that only military force would drive the British out of Palestine. Then he asked, “Are you also in favor of violence against us?”

Dayan said he was a soldier, and would follow orders.

This first meeting was the beginning of a fateful relationship. The two men stood across a wide divide of ideology and tactics that would threaten to bring the Jews to civil war. In November 1944, Haganah cracked down on Irgun and an even more violent splinter group known as the Stern Gang (also known as Lohamei Herut Yisrael or LEHI). Ben-Gurion saw them as a threat to the consolidation of power in the incipient Jewish state and tried to crush them. Irgun members were kidnapped; some were locked up in makeshift dungeons and others turned over to the British. Some were even tortured. Children of Irgun members were expelled from school; Irgun sympathizers were fired from their jobs. Although his followers were howling for revenge, Begin refused to retaliate. He decreed that Jews must not be harmed. His ability to keep his men in line made a profound impression, even among the Haganah. A new picture of Begin was emerging—that of a patriot with a nearly mystical attachment to Jewish lives. If he had chosen to respond in kind to Haganah’s attacks, the community would have been torn utterly apart, but his willingness to endure persecution for the sake of peace among Jews lent him and his movement an aura of martyrdom.

When the Second World War came to an end, Europe was overrun with Jewish refugees, but Western democracies closed their doors to them. In some cases, refugees who had gotten as far as the docks of Palestine were turned around and sent to “displaced persons” centers in Germany right next door to the concentration camps where they had formerly been imprisoned.

In July 1945, Churchill suffered a surprising defeat. Zionists were thrilled because the incoming Labour Party had been so supportive of their cause, but they were quickly disillusioned when the new government decided to maintain the same restrictive immigration policies of its predecessor. In the minds of many Jews in Palestine, Begin—the fanatic, the terrorist—had been proved right.

Ben-Gurion decided that Haganah should temporarily join forces with Begin’s Irgun and the Stern Gang in a united resistance against the British. The pace and scale of the attacks ramped up dramatically, and so did the British response. By 1946, there were more than a hundred thousand troops in Palestine—about one British soldier for every adult male Jew in the country. In a single immense sweep on June 29, which came to be called “Black Sabbath,” the British picked up three thousand suspected members of the resistance. At that point, Ben-Gurion decided the revolt had become too hazardous. But he had allowed one last operation to be put in motion, the biggest one of all.

The elegant King David Hotel in Jerusalem was not only the center of the country’s social life, it was also the headquarters of the British Administration, which had set up offices on two floors of the southern wing of the highly secure building, which the hotel had been designed to withstand earthquakes as well as aerial bombardment. There had been numerous threats made against the facility but the British chief secretary, John Shaw, chose to ignore them. “We must retain, as far as possible, normal conditions,” he told his subordinate, “and you can’t take a last place of amusement away from the people.”

Posing as Arab waiters, Begin’s men smuggled seven large milk churns, each packed with seventy pounds of TNT, into the basement through the kitchen of the restaurant. Upstairs, diners were being seated for lunch in the posh Café Régence. At 12:10 p.m., an anonymous woman called the switchboard and said that the hotel had been mined. “Evacuate the entire building!” But somehow the news did not reach the diners or the hotel guests. Begin would later blame the British for not heeding the warning, and in particular, John Shaw. He spread a rumor that Shaw had declared he was there “to give orders to the Jews and not to receive them.” Shaw claimed there was no warning at all.

At 12:37, the city was shaken by the blast, which sheared off the southern wing of the once impregnable six-story hotel and left a mound of smoking rubble in the street. The silence that followed the great noise was soon broken by the cries of the wounded. Two weeks later, when emergency workers had finally sorted through the shattered stones, twisted girders, splintered furniture, and the detritus of offices and hotel rooms and kitchenware and plumbing pipes, they counted ninety-one dead, including twenty-eight British, forty-one Arabs, seventeen Jews, two Armenians, a Russian, a Greek, and an Egyptian.

A distraught Begin listened to the report of the casualties on the BBC, which was followed by the playing of a funeral march. One of his aides, concerned about Begin’s mental state, removed a tube from the radio so he couldn’t listen anymore.

Haganah ordered Begin to take sole responsibility, which he loyally did. Ben-Gurion then denounced the operation, although according to Irgun he had secretly authorized it. “The Irgun is the enemy of the Jewish people,” the prime minister publicly declared. “It has always opposed me.”

Begin admitted that the fact that innocents were killed caused him “days of pain and nights of sorrow,” but his grief was circumscribed. “We mourn the Jewish victims,” he said on the radio afterward. “The British did not mourn the six million Jews who lost their lives, nor the Jewish fighters the British have murdered with their own hands. We leave the mourning for the British victims to the British.” He neglected to mention the other victims, including the Arabs, who made up the largest number of fatalities.

During the manhunt that followed, Begin hid in a secret compartment in his house for four days without food or water. A wanted poster was circulated by British authorities with a photo of Begin, slightly frowning and staring evenly at the camera with an implacable expression. The poster described him as “5ft. 9in.”—he was actually about three inches shorter—“medium build, long hooked nose, bad teeth, wears horn-rimmed spectacles.” The search was confounded by the abundance of misinformation in the British files. “He may be a Soviet agent,” the British Foreign Office speculated. “He was made ‘better-looking’ by a German-Jewish doctor in Cairo,” a British newspaper asserted. “It is likely the flat feet and bad teeth have also been remedied.”

As Begin had hoped, the King David bombing exhausted the will of the British people to continue the Mandate. They were already spending more on Palestine than on their own domestic health and education. In February 1947, Britain announced it was turning the problem of Palestine over to the UN, saying the Mandate had proved “unworkable.”

Sensing victory, Begin stepped up the attacks—sixteen on a single day in March, including a bomb in a British officers club that killed twelve. When teenage members of his Irgun gang were arrested and flogged by the British, Begin warned that British officers would be treated in the same demeaning fashion, stroke for stroke. No doubt the childhood memory of Polish soldiers flogging Jews in Brisk flooded his mind. “For hundreds of years you have been whipping ‘natives’ in your colonies—without retaliation,” an Irgun message stated. “Jews are not Zulus. You will not whip Jews in their homeland.” Britain stopped this practice after four of its soldiers were captured and flogged. The news of this event went all over the world, in part because of the equivalence in human worth that Jews had dared to make with their British occupiers.

Begin soon posed an even more insulting challenge to British authority. Early on the morning of July 29, the British hanged three Irgunists convicted of terrorist crimes. That very same morning, Begin’s men hanged two British soldiers and booby-trapped their dead bodies. Begin, the lawyer, justified the murders by saying that the soldiers, who had been randomly kidnapped, had been court-martialed for “anti-Hebrew activities.”

Many Jews were appalled by this action, not only by the murder of the British sergeants but also by Begin’s legal sophistry. There was an immediate and virulent eruption of anti-Semitic attacks all over Britain—synagogues burned, shops looted. Outraged British troops went on a shooting spree in Tel Aviv, killing five civilians. And yet Begin’s strategy had worked. The hanging of the British sergeants tipped the scale of public opinion in the UK decisively against the Mandate.

Terror was not the only reason that the State of Israel finally came into being, but the Irgun campaign was a critical factor in driving the British out of Palestine. Begin was the first terrorist to grasp the value of publicity in promoting his cause to an international audience. The transformation of terrorism from a primarily local phenomenon into a global one came about in large part because of the success of his tactics. He pioneered techniques that would become basic terrorist strategy, such as simultaneous bombings and the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). He proved that, under the right circumstances, terror works. Many years later, American forces would find a copy of Begin’s memoir The Revolt in the library of an al-Qaeda training camp. Osama bin Laden read Begin in an attempt to understand how a terrorist transformed himself into a statesman.

Begin always disputed that he had engaged in terror. He wrote that his object was “precisely the reverse of ‘terrorism,’ ” because the point of his struggle was to free Jews from their chief affliction—fear. He concludes, “Historically we were not ‘terrorists.’ We were, strictly speaking, anti-terrorists.”