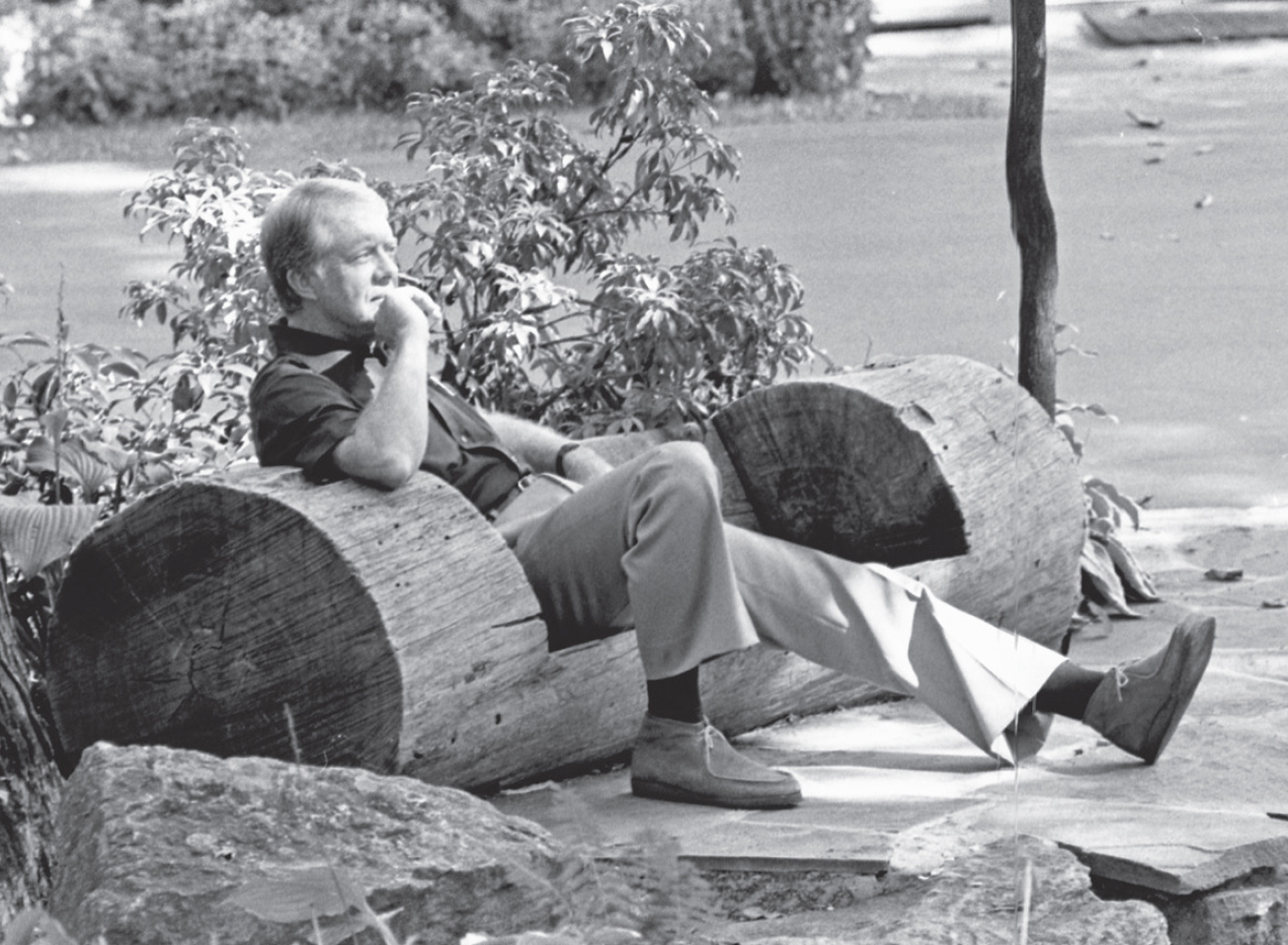

Jimmy Carter beside Camp David fish pond

Jimmy Carter beside Camp David fish pond

AFTER BREAKFAST on the morning of September 7, Carter and his top aides, Vance and Brzezinski, met with Begin, Dayan, and Weizman. Begin was in full fury. Carter tried to placate him by agreeing that Sadat’s proposal was “very tough.” He asked the Israelis if they could make some concession that would help change the mood of the summit; otherwise, it would all end very soon. Begin ignored his plea, insisting on going through the Egyptian proposal line by line, treating individual words and phrases as if he were spitting out poison. “Palestinians!” he exclaimed. “This is an unacceptable reference. Jews are also Palestinians.” “Conquered territory! Gaza was also conquered by Egypt.” Carter pointed out that Egypt was not laying a claim to Gaza, which was now under Israeli control. As Begin continued to tear into the Egyptian document, Carter realized how much the prime minister valued it as a foil to avoid addressing the issues.

“What do you actually want for Israel if peace is signed?” Carter said, nearly shouting in frustration. “How many refugees and what kind can come back? I need to know whether you need to monitor the border, what military outposts are necessary to guard your security.” He added, “My greatest strength here is your confidence—but I don’t feel that I have your trust.”

“We wouldn’t be here if we didn’t have confidence in you,” Weizman protested.

“You are as evasive with me as with the Arabs,” Carter responded. He said it was time to stop “assing around” and put their cards on the table. “Throw away reticence. Tell us what you really need.” The discussion got out of hand. Carter accused Begin of wanting to hang on to the West Bank, and said that his offer of autonomy was really just a “subterfuge” to keep the territory under permanent control.

Begin bridled at having his integrity questioned. Then he turned again to the Egyptian proposal, claiming it would force Jews to become a minority in their own country. That’s the kind of peace Sadat was seeking, he contended—with an Israel doomed by the very terms of his offer.

“Sinai settlements!” Begin continued, in his endless refutation of the Egyptian proposal. “There is a national consensus in Israel that the settlements must stay!”

At the outset of the Camp David summit, Sinai had seemed to be the issue most easily resolved, but Carter would come to the conclusion that it was, in fact, the most difficult of all. It was where the trouble all began.

THE BIBLE AND THE QURAN tell very similar stories about the origin of the conflict between the Egyptians and the Israelites. For four centuries, large numbers of Israelites were living and prospering in Egypt, growing into a great nation. Then a new pharaoh arises who is suspicious of the Israelites. Worried that they are becoming too numerous and pose a threat, Pharaoh turns the Israelites into slaves and orders that every male child born among them be thrown into the Nile.

One day, Pharaoh’s daughter (in the Quran, it’s Pharaoh’s wife) discovers a beautiful child floating in a wicker basket among the reeds of the river. This is Moses. The daughter is enchanted and adopts Moses into the royal household. Because the baby refuses to suckle at an Egyptian’s breast, the child’s actual mother is summoned to act as a wet nurse. Moses is raised as a prince, but he is always aware that he is a Hebrew. When he witnesses one of his enslaved kinsmen being beaten by an Egyptian overseer, he strikes the assailant and kills him. He spends the next four decades in exile, fleeing the wrath of Pharaoh, living as a nomadic shepherd in the land of Midian, across the Red Sea.

While tending his flock at the base of Mount Sinai, he investigates a strange fire on the slope. He finds a bush aflame, and yet it is not consumed by the blaze. “Moses,” a voice cries out from the flames, “I am God, the Lord of the Worlds!” The Lord tells Moses that he has taken pity on the Israelites. For the first time, God has decided to actively shape human history by taking the side of the Jews. “I have come down to rescue them from the Egyptians and to bring them out of that land to a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey.” He appoints Moses to lead his people out of Egypt.

Moses returns from Sinai to confront Pharaoh. “Let my people go,” he demands. When Pharaoh refuses, Moses and his brother Aaron cast a spell, turning the Nile into a river of blood. God sends a series of devastating plagues—frogs, boils, lice, flies, wild animals, hailstorms, locusts, and days of darkness—to harry the Egyptians until Pharaoh relents. Again and again, Pharaoh promises Moses, “If you remove this plague from us, we will truly believe in you and let the children of Israel go with you!” The Quran says that each time a plague is lifted, Pharaoh changes his mind and rejects his pledge to free the Israelites. The Bible says that God intentionally hardened Pharaoh’s heart, telling Moses that he is doing so in order to make a point, “that you may tell in the hearing of your son and of your son’s son how I have made sport of the Egyptians and what signs I have done among them; that you may know that I am the Lord.”

Finally God instructs Moses and Aaron to tell their people to slaughter a yearling lamb and smear its blood on their doorways. “I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will smite all the first-born in the land of Egypt, both man and beast,” he says. “When I see the blood, I will pass over you, and no plague shall fall upon you to destroy you, when I smite the land of Egypt.” In memory of this miracle, Jews celebrate Passover each year. At the Seder, a drop of wine is spilled for each of the ten plagues, to signify that the joy of the Jews because of their liberation is diminished by the suffering inflicted on the Egyptian people.

When Pharaoh awakens to find his own first-born son among the dead, he summons Moses and entreats him, “Go forth from among my people, both you and the people of Israel.” The Israelites quickly gather their belongings, but also take the time to demand jewelry and clothing from the ruined Egyptians.

But God isn’t finished with Pharaoh and his people. Once again, he hardens the heart of the ruler and causes him to summon his chariot and marshal his entire army. The Egyptian force chases the Israelites and catches up to them on the shore of the Red Sea. The cornered Israelites cry out to Moses, “Is it because there are no graves in Egypt that you have taken us away to die in the wilderness?” Moses responds by lifting his rod, whereupon a great wind rises up, parting the waters of the Red Sea. The Israelites cross into Sinai, but when the Pharaoh and his army pursue them, the Lord causes the waters to return and swallow them up. Not a single soldier survives. Moses and his people stand on the far bank and marvel at the sight, and they sing out,

My strength and my refuge is the Lord,

and he has become my savior.

This is my God, I praise him;

the God of my father, I extol him.

The Lord is a warrior,

Lord is his name!

“We saved the Children of Israel from their degrading suffering at the hands of Pharaoh,” the Quran concludes.

For the secular Jews who created modern Israel, the story of the Israelites’ presence in Egypt, and the Exodus, and the arrival in Canaan three thousand years ago is a testament to Jewish title to the land. History and archeology combine to tell a different story, however. There may have been Jews in Egypt, but there is no documentation by the ancient Egyptians—scrupulous record keepers—of their presence. It is possible that the biblical chronology is wrong. There was a Semitic people called the Hyksos who invaded and occupied part of Egypt before they were forcibly expelled more than a hundred years before the Exodus is supposed to have taken place; however, Israel is not cited in the inscriptions from the Hyksos period. A national trauma such as the drowning of a pharaoh and his army is not mentioned in Egyptian records.

According to the Bible, the Israelites who followed Moses numbered 603,550 men above the age of twenty, plus their wives and children, livestock, and a multitude of non-Israelites who accompanied them—a horde of at least 2.5 million people. Marching ten abreast, they would have stretched more than 150 miles. That would span the entire width of the peninsula. Many miracles supposedly occur on the journey. In the barren desert, God provides fresh water and provisions—in particular, manna, a divine substance that falls from heaven each night and sustains Moses and his people for the forty years that they wandered in the Sinai wilderness. The Lord instructs them not to eat more than their daily ration, except for the sixth day, when they are to gather enough for two days, so that they can rest on the seventh.

As the Children of Israel attempt to reach the Promised Land, they are set upon by the Amalekites, a tribe of nomads, who prey on the stragglers. The Lord is so infuriated that he instructs the Jews to annihilate the Amalek tribe entirely: “Do not spare him; kill men and women, children and infants, oxen and sheep, camels and donkeys.” In Jewish lore the Amalek came to be seen as a mythic enemy of the Jews that is eternally recreated. In the first evening of the Passover service, when Jewish families around the world recite the story of the Exodus, they are reminded that in every generation there is someone that will rise up in order to destroy the Jewish people. Menachem Begin would be guided by this admonition. In his parents’ generation, it was the Nazis; for him, it would be the Arabs.

Three months after the Israelites escape from Egypt, God calls Moses to meet him atop Mount Sinai, the place where He first revealed himself in the burning bush. When the Lord descends onto the mount, heralded by lightning and thunder and trumpet blasts, the summit blazes, and the people quiver in fear. The Lord speaks to Moses, issuing the Ten Commandments, followed by a long list of ordinances, such as how to treat slaves and sorcerers and cattle thieves. Twice God reminds Moses to be generous to strangers, “for you were once aliens residing in the land of Egypt.” In addition, the Lord promises to send an angel to lead the Children of Israel into the land of milk and honey—which inconveniently happens to be occupied by a number of other tribes. “Little by little I will drive them out before you,” the Lord pledges, “until you have grown numerous enough to take possession of the land. I will set your boundaries from the Red Sea to the sea of the Philistines [i.e., the Mediterranean], and from the wilderness [Sinai] to the Euphrates.” Elsewhere in the Bible, God specifically awards the land of Canaan to Moses, describing its boundaries as roughly encompassing those of modern Israel, but including much of southern Lebanon and the West Bank of the Jordan River.

The vast migration through Sinai that the Bible describes—millions of people tramping about for forty years—should have left some archeological residue, but not a single scrap of evidence exists to prove that the Exodus ever happened. The archeological record seems to show that the ancient Hebrew people were a Bronze Age tribe native to the Canaan region—a province of Egypt at the time the Exodus is supposed to have taken place, a fact the Bible does not mention. That would give Egypt an equal claim on present-day Israel with that of the Jews, if antiquity is the yardstick used to measure territorial rights.

The Quran accepts the premise that God awarded the Holy Land to the Israelites, but asserts that the people were disobedient and God turned against them, revoking their special status as the Chosen People. “But they broke their pledge, so We distanced them and hardened their hearts,” God says of the Jews; “you will always find treachery in all but a few of them. Overlook this and pardon them.”

AT TEN THIRTY on the morning of the third day at Camp David, Carter and Begin walked together to Aspen Lodge just in time to meet Sadat coming from the other direction. Begin, with his granitic sense of protocol, refused to enter the cabin before the two presidents, which caused a rather comic and awkward start to the proceedings. Carter began by asking Begin if he could make a generous concession that would respond to Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem. The prime minister brushed this overture aside, saying that the Israeli people had already rewarded Sadat by their warm reception. It should not be forgotten, Begin continued, that only four years before, on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, Sadat had launched his surprise attack, “knowing we would all be in the synagogues.”

“It was strategic deception,” Sadat responded.

“Deception is deception,” Begin said. He then took up Sadat’s proposal, going through it once again point by point, ridiculing the language in brutal fashion. The men seemed unable or unwilling to understand each other. Begin contented that the Egyptian document laid the groundwork for a Palestinian state. “We will not allow the establishment of a base for Yasser Arafat’s murderers within our borders, including the redivision of Jerusalem. There can be no agreement on the basis of these demands.”

“No! I said already yesterday that there is no need to divide Jerusalem,” Sadat protested.

“You address us as if we were a defeated nation,” Begin said, talking past him. He clung to Sadat’s document like a prosecutor waving the murder weapon in front of the jury. “You demand we pay compensation for damages incurred by Egyptian civilians,” he continued. “I would like you to know that we also claim damages from you.”

This set Sadat off. At that very moment, Israel was still pumping oil from the Sinai wells that properly belonged to Egypt, Sadat said indignantly. Begin made another provocative remark about being treated like a defeated nation, which brought up the question of who actually lost the war of 1973. Carter interceded to say that neither side was claiming to represent a defeated nation. They calmed down for a moment, but the grievances of both parties were burning hot, and neither man seemed inclined to hear the other.

Sadat angrily recited the suffering that four wars had inflicted on the Egyptian people. Carter tried to interrupt, but Sadat waved him aside. “I thought that after my initiative there would be a period of goodwill,” he complained to Begin. “We are giving you peace and you want territories.”

Begin replied that Israel merely wanted a defensible situation.

“I also want to defend Egypt!” Sadat shouted. Whenever he lost his temper, Sadat tended to call Begin “premier” rather than “prime minister,” which irritated Begin. Now Sadat leaned forward in his chair and accused the Israeli leader of not wanting peace at all. Stabbing the air with his finger he exclaimed, “Premier Begin, you want land!”

The two men no longer seemed aware of Carter’s presence. Their faces were flushed and their voices unrestrained. Rosalynn was in the next room, and she could hear the leaders screaming at each other. Sadat pounded the table and declared that land was not negotiable. For thirty years, he said, Israel had sought security, an end to the Arab boycott, and full recognition—and here it was, on the table! If Begin continued to insist upon holding on to territory then the discussion was over. “Security, yes! Land, no!” Sadat cried. No Israelis could remain in Sinai. Egyptian territory must be “clean-shaved.”

The presence of a few Israeli settlers in Sinai was not an infringement on Egyptian sovereignty, Begin responded, infuriating Sadat even further. All the good feelings his trip to Jerusalem had engendered had gone up in smoke, Sadat said. “Minimum confidence does not exist anymore since Premier Begin has acted in bad faith.”

Weirdly, there were moments when Sadat and Begin burst into spells of levity. One of the men referred to kissing Barbara Walters, and wondered if the cameras had been on and his wife was watching. Another time, they bickered about who was responsible for the trade in hashish between Israel and Egypt in Sinai. This struck them both as hilarious.

After three hours of exhausting interchanges, the leaders recessed to consult their advisers in advance of the next session that afternoon. Before they broke up, Carter recited a list of all the problems that remained to be resolved:

Sinai. If it was to be demilitarized, what did that mean? Was it the entire peninsula or could the Egyptians station troops to protect the canal? Would police be allowed in Sinai to maintain order?

Settlements. Begin refused to dismantle any settlements anywhere; Sadat demanded that they all must go, not only in Sinai but also in the West Bank and Gaza and the Golan Heights.

An independent Palestinian state. This was Begin’s biggest fear; he would assert that any compromise on the West Bank and Gaza was a gateway to a state for terrorists. Sadat thought an independent state was inevitable, but he preferred that whatever entity emerged be affiliated either with Israel or Jordan. The Palestinians themselves should be allowed to choose. The fact that the Palestinian movement was led by Yasser Arafat, who had been the head of the terrorist organization Fatah, made this issue diplomatically radioactive.

Palestinian autonomy. Begin claimed that Israel would be very generous in granting Palestinians “full autonomy,” but in Carter’s opinion the evidence was to the contrary. Begin wanted to keep the land and rule over the people through a puppet government that didn’t have final authority.

Israeli military presence in the West Bank and Gaza. If the Palestinians were indeed to be given some kind of autonomy, how would Israel guarantee its security without having a military government overseeing the region? Would it be able to station forces in the territories?

The West Bank. Begin maintained that UN Resolution 242 simply didn’t apply to the West Bank, because when Israel seized the territory in 1967 it was a defensive war. Thus, he argued, the victor was entitled to keep the land. Sadat was somewhat flexible on borders but not on the principle that the West Bank belonged to the Palestinians.

Jerusalem. Under the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which created the State of Israel, Jerusalem was envisioned to be an international city that was not under the rule of any other entity. Begin, however, was not willing to budge on anything having to do with Jerusalem.

What peace means. In addition to ending the state of war, there should also be trade, open borders and waterways, and an exchange of ambassadors, although Sadat sourly suggested he was reconsidering diplomatic recognition because of Begin’s poor attitude.

Refugees. There were approximately 750,000 Palestinians who fled during the war of Israel’s creation in 1948, and another 300,000 or so who became refugees in 1967. Many of them and their descendants were living in refugee camps in neighboring countries, stateless, often in squalid conditions. How many of them could return to Israel? How many would even be allowed back into the West Bank? What compensation would be given to those not allowed to return? The fact that the Palestinians were not represented in this summit made it difficult to arbitrate on their behalf.

The Sinai airfields. Israel had ten on the peninsula, only two of them significant. Begin suggested that the U.S. could take over the operation of the bases, allowing the Israelis to continue using them. Sadat adamantly rejected this plan.

There were several other points, regarding participation by other Arab countries and the establishment of a mutual defense treaty between the U.S. and Israel. Both Begin and Sadat were in favor of this because it would eliminate Israel’s chronic complaint about security needs, but Carter was reluctant to formally ally himself with one of the partners. It would make it impossible in the future to mediate between Israel and the Arab countries.

When Carter finished reading his list, he was depressed. The problems were overwhelming. There were so few areas of agreement. He had no idea where to go next. These were problems that were built into the creation of Israel itself, thirty years before.

IN NOVEMBER 1947, the UN voted to divide the territory of Palestine into two states, 56 percent for Jews and the remainder for Arabs. Jerusalem would be an international zone, available to all three religions but governed by an independent body. The plan was never given a chance. On May 14, 1948, the British formally left Palestine, and the State of Israel was born. The next day, armies from Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Transjordan, and Egypt approached from the north, east, and south in an attempt to destroy the Jewish state.

It is interesting to imagine what might have happened if we could have stopped those Arab armies in their tracks, before the cascade of wrongheaded decisions, and let history take an alternative course. None of the surrounding Arab countries favored the creation of Israel, but they were also opposed to a Palestinian state. King Abdullah of Transjordan had previously sought an accommodation with the Jewish leaders in order to annex the West Bank and Gaza and gain precious access to the Mediterranean, but his rival Arab leaders were determined to prevent the Hashemite king from expanding his domain. Both Egypt and Iraq aspired to replace the defunct Ottoman Empire. Each of these Arab powers was primarily interested in blocking the aspirations of the others, but their predatory instincts were also aroused. The Palestinians themselves were weak and leaderless. Thus, the Israeli-Palestinian problem was Arabized instead of subsiding into a two-party dispute.

In turning against Israel, Arab societies also turned against the Jews in their midst. There were about 800,000 Jews living in Arab countries in 1948, 75,000 to 80,000 in Egypt alone. Mass detentions, bombings, and confiscations of their property prompted the Arab Jews to pack their bags, taking with them their investments, their long history, and the cosmopolitanism that once infused urban centers from Morocco to the Levant. Today, only remnants of the Jewish population exist in Arab countries, where any Jews remain at all. Arab culture and society were profoundly diminished by this modern exodus; and in the absence of actual Jewish neighbors, a simplistic and reflexive anti-Semitism took hold. Many of those refugees found their way to Israel, replacing the Palestinians who fled or were chased out of the contested land.

Egyptian military leaders advised against intervening in the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. The army was weak, poorly trained, and inadequately armed. Egypt was still occupied by the British, and many Egyptian nationalists argued that war in Palestine would be a needless and dangerous distraction; a wiser course would be to strike a deal with the Jews to use their influence with Britain and the U.S. to support Egyptian independence. But the decadent King Farouk, who pictured himself as the new caliph of the Muslims, decided otherwise, and so he sent his ragged, ill-prepared army into battle. The Egyptian Army officers “didn’t think about the possibility of victory or defeat,” Sadat would later write. “They thought about one thing only, that a war had been announced in the name of Egypt, and Egypt’s army must wage this war as bravely as any army wages war, and its men must die, officers and soldiers, in sacrifice for every kernel of the wealth of the Holy Land, for Arab unity, glory, history, and piety.” Those high-minded abstractions were scarcely equal to the commitment of a people who were fighting for their very existence.

Although five Arab countries attacked the new nation, it was not really such a one-sided contest as legend would have it. The total number of Arab troops fielded at the beginning of the war was 25,000, whereas the Israel Defense Forces had 35,000 troops, a number that increased to nearly 100,000 by the end of the war in 1949—about twice the size of its foes. Egypt attacked from the south, through Sinai, getting within twenty miles of Tel Aviv and bombing the city several times before encountering the newly formed Israeli air force. Ezer Weizman had created it with five or six light planes—Piper Cubs and Austin biplanes—commandeered from the Palestine Aviation Club. By the start of the war the corps also included four brand-new Messerschmitts. Weizman himself flew one of them in the air force’s first action, strafing an Egyptian armored unit that was bearing down on Tel Aviv. The sky was thick with anti-aircraft fire, and the Messerschmitts had never actually been flown before. “We swung out to sea, climbing to 7,000 feet, and swooped toward the Egyptian column,” Weizman recalled. “I must confess I had a profound sense of fulfilling a great mission.” That first run was scarcely a success: one of the four Messerschmitts was shot down, and Weizman’s cannon jammed; but the Egyptian troops were shocked and sensed that they had already lost control of the air.

The war provided an opportunity for the new Jewish nation to reshape itself, not only geographically but also demographically. Many Palestinians fled the conflict, under the impression that the Arab victory would be swift and they could soon return to their homes. But many others were forced out. Dayan was put in charge of a commando unit, Regiment 89, soon noted for slashing raids into Arab towns, his troops killing indiscriminately, feeding the panic that led to the mass exodus of Palestinians. He led his men into the city of Lydda (near the site of what is today called Ben Gurion Airport), where they shot everyone they saw—more than a hundred civilians in less than an hour. The next day, the Israeli army carried out a systematic massacre of hundreds more and the expulsion of thousands of the town’s surviving citizens, many of whom would die on the trek toward the ruined lives that otherwise awaited them. They joined hundreds of thousands of others who swelled the refugee camps of neighboring countries, destabilizing those governments and opening an era of terror that continues to find its justification in the loss of a nation that never actually got the chance to exist. The 1948 war would leave Egypt in control of Gaza, and Jordan with the West Bank, including the Old City of Jerusalem. Israel annexed eight thousand square miles, giving it three-fourths of the territory of the British Mandate. So much for Palestine.

The Arab defeat would have shattering consequences for those societies. Humiliated in battle, the soldiers returned to take revenge on their governments. Military coups, one after another, turned the region into a vast barracks state. To justify their continued hold on power, the military rulers had to enshrine a permanent enemy, and the one they could all agree upon was Israel. Peace would ruin everything.

ONE OF BEN-GURION’S MAIN TASKS during the War of Independence was to gain control of the underground movements, especially Begin’s Irgun. As Israel’s first prime minister, Ben-Gurion did not want his country riven by private militias contending for power. Even though Irgun nominally had been disbanded and its members integrated into the Israeli army, Begin still commanded a fanatically loyal following. His greatest worry was that the Arab countries would accept the partition plan and that the war would end, forcing Israel to remain inside the borders that it had been awarded. That seemed to be its destiny on June 11, 1948. The UN had brokered a cease-fire between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Both sides agreed not to bring in any more arms. UN observers were straining to enforce the ban.

At this delicate moment, a boatload of French arms, purchased by Irgun and valued at more than five million dollars, arrived off the Israeli coast. The Altalena dropped anchor at nightfall opposite a village named Kfar Vitkin, north of Tel Aviv. Begin emerged from the underground and greeted the vessel. He was still unused to being in public, and many of his Irgun followers had never actually seen him. Some of them wept to discover their commander standing in front of them.

The shipment was supposed to have arrived before the cease-fire went into effect. There was an agreement with Ben-Gurion that the Irgun would receive 20 percent of the munitions and the Israeli army would get the rest, the Israeli prime minister suddently became convinced that Begin intended to stage a coup d’état. He excitedly told his cabinet, “It’s an attempt to run over the army and murder the State.” He sent Lieutenant Colonel Moshe Dayan to Kfar Vitkin to confiscate the entire shipment.

Dayan found members of Irgun unloading the shipment. He thought it would be sufficient to spread his men around the beach and say, “Enough! You’re surrounded.” Begin defied the ultimatum, however, instructing his men to continue unloading the cargo. Although guns were drawn on both sides, Begin scoffed at the possibility that violence would break out. “Jews do not shoot at Jews!” he confidently told a subordinate. But then automatic weapons crackled, followed by mortar fire.

Who fired first became a matter of dispute. “Our men called on Irgun to give themselves up,” Dayan recalled. “Their reply was a volley of fire in which eight of our men were hit, two fatally.” According to Begin, “Suddenly, we were attacked from all sides, without warning.” Six of his men were also killed. When Begin refused to leave the beach voluntarily, his followers wrestled him aboard a launch to get him to the Altalena. Trailed by Israeli warships, the Altalena steamed toward Tel Aviv, where Begin’s supporters were gathering in force. So was the Israeli army.

In its panicked flight, the Altalena came aground just off the coast of Tel Aviv, in front of the Kaete Dan hotel, which served as the headquarters for the UN as well as a watering hole for diplomats and foreign journalists. They stood on their balconies watching in gape-mouthed astonishment as Israeli forces strafed the stranded ship and even shot at Irgunists swimming toward the beach. The captain ran up a white flag, but Begin demanded that he take it down. “We must all perish here,” he proclaimed. “The people will rebel. A new generation will come to avenge us.” Then a shell struck the cargo hold, fire engulfed the Altalena, and the ammunition stored below began exploding. The captain gave the order to abandon the sinking vessel. Begin, who couldn’t swim, was again forced into the launch, while protesting that he wanted to go down with the ship. Sixteen of his men were killed and dozens wounded. Three members of the Israeli Defense Forces were also killed.

Once ashore, Begin rushed to a radio transmitter to convey his account to the Israeli public before the government had a chance to put its stamp on it. He was terribly distraught and in no condition to make a speech. He wept and screamed. At times, he was incoherent. He called the attack “the most dreadful event in the history of our people, perhaps in the history of the world.” His speech was a disaster, all the more so because he punctured the legend of mystery that had surrounded him while he was underground. He turned what might have resulted in a national outcry against Ben-Gurion into a bathetic display of self-pity. His career as a leader of an underground movement was over. He went into seclusion, a broken man. It was then that he decided to reinvent himself as a politician.

AT FIVE P.M., the three principals reconvened in Carter’s small office. Sadat was still fuming from the morning meeting, insisting that he had nothing more to add. Begin suggested that they return to what he saw as the main issue, Israel’s security needs in Sinai. He reminded Sadat that King Farouk, President Nasser, and President Sadat himself had each attacked Israel from Sinai. The settlements there served as vital outposts for Israel’s protection.

“Never!” Sadat said adamantly. “If you do not agree to evacuate the settlements, there will be no peace.”

“We will not agree to dismantle the settlements,” Begin replied stonily. “The opposition in Israel will not agree to it either.”

The Egyptian people genuinely long for peace, Sadat argued, but “they will never accept an encroachment on their land or sovereignty.” Any remaining Israeli settlements in Sinai would be an absolute insult to Egypt, he said. “I have tried to provide a model of friendship and coexistence for the rest of the Arab world leaders to emulate. Instead, I have become the object of extreme insult from Israel, and scorn and condemnation from the other Arab leaders.” He added: “I still dream of a meeting on Mount Sinai of us three leaders, representing three nations and three religious beliefs. This is still my prayer to God!”

It was a characteristic moment for the Egyptian leader. Under stress, his idealism spread its wide wings. He became emotional and took any setback extremely personally. Begin, his opposite in so many ways, became colder and more analytical, marshaling data to try to win debating points while dismissing the broader perspective that Sadat tried to place on the table. “Anyone observing the two men could not have overlooked the profound divergence in their attitudes,” Weizman later recalled. “Both desired peace. But whereas Sadat wanted to take it by storm … Begin preferred to creep forward inch by inch. He took the dream of peace and ground it down into the fine, dry powder of details, legal clauses, and quotes from international law.”

Ignoring Sadat’s dream, Begin said that there were only about two thousand Israelis in thirteen settlements in Sinai—so why couldn’t Sadat just convince the Egyptian people to accept them as permanent residents who posed no military threat to Egypt and no infringement of their sovereignty?

Sadat had had enough. He said he saw no reason for the talks to continue. He stood and stared sternly at Carter.

Carter was desperate. He had gambled his career on Camp David, but more than that, he had placed a bet on human nature. He firmly believed that men of goodwill, representing the interests of their people and with history looking over their shoulders, would acknowledge that the benefits of peace were so great that they must find a way to achieve it. But war makes its own compelling argument. Hatred is so much easier than reconciliation; no sacrifices or compromises are required. War holds out the promise of victory, and with it the enticing prospect of redemption from the humiliation of the past. Revenge always wants to be satisfied before peace can come to the table. There is a natural human tendency to inflict on others the indignity one has had to endure. Israel and the Arab world were two anguished cultures that could only be healed by making peace with each other; but their wounds preoccupied them. The anger and willful misunderstanding that had characterized the talks so far were the language of war, not peace.

Carter temporized. He outlined areas of agreement, but there were few to point to. He warned that failure at Camp David could lead to a world war. He said he couldn’t believe that the Israeli people would prefer settlements in Sinai to peace with Egypt. He suggested to Begin that, if he couldn’t bring himself to make the sacrifice, he should go to the Knesset and ask that they make the decision about dismantling the settlements. “I’m sure you will get an overwhelming majority,” he said.

The Israeli people would never accept it, Begin replied; moreover, it would spell the end of his government. He would be willing to accept the consequences if he believed that it was the right thing to do, but he absolutely did not believe it.

By now both Begin and Sadat were heading toward the door. Carter physically blocked their path. He begged them for one more day so that he could devise a compromise. Begin agreed. Carter looked at Sadat, who finally nodded his head. Then the two men left without speaking to each other.

THAT EVENING the Carters had arranged a party. They had thought that by now the delegations would be hammering out the final details of an agreement, and this would be a kind of celebratory break. Bleachers were erected around the helicopter landing field, and Marines conducted their famous Silent Drill—marching in close order, with bayonets on their rifles, and performing their intricate movements in total silence. The grim-faced audience in the bleachers also sat in total silence. There was a light mist in the air, which made the blades gleam as the rifles twirled. Moshe Dayan, who had written the training manual for the Israeli army, watched the display with quiet contempt. Such a display belonged in a circus, he thought, not on a military parade ground.

Since the start of the summit, the press had been shuttered miles away from the grounds. Daily press conferences were held at the American Legion Hall in nearby Thurmont, Maryland, which boasted the tenuous claim of being the “goldfish capital of the world.” Hundreds of journalists had commandeered every available room in the region. ABC News had secured an entire motel, turning it into a remote bureau, complete with a blimp carrying a satellite dish several hundred feet above the scene. Each day, White House press secretary Jody Powell fed hundreds of journalists little more information than what the delegates had for breakfast and the precise times that they met. The reporters were ravenous for real news. For this one occasion, they were bused to the Camp David grounds and allowed to observe the delegates from a distance. What they saw were the three leaders with fixed expressions, not exchanging a single word, watching a military pantomime. It seemed clear that the talks had broken down.

After the drill, as the Marine Band struck up a medley of patriotic songs from the three countries, the press was ushered back to the buses. Gerald Rafshoon, Carter’s media adviser, was checking to make sure everyone was aboard, but he discovered that Barbara Walters was missing. She was finally located, lurking in the ladies’ room.

When the press departed, there was a reception with a string quartet for the delegates. The Carters had made a great effort to get the Egyptians and the Israelis to mingle. A buffet was spread on different tables inside Laurel Lodge and on the patio in order to encourage people to circulate. Rosalynn sat with Sadat on the low brick wall around the patio. She had noticed how forlorn he appeared, especially as the patriotic music was playing. Sadat couldn’t even bring himself to mention Begin’s name. “I’ve given so much and ‘that man’ acts as though I have done nothing,” he told her. “I have given up all the past to start anew, but ‘that man’ will not let go of the past.” Rosalynn tried to reassure him, reminding him that the whole world admired his courage and was watching Camp David hoping for a breakthrough. She added that sometimes when healing words such as his are said it takes a little time for them to soak in. Sadat was inconsolable. “I would do anything to bring peace to our two countries,” he said. “But I feel it is no use.”

Carter and his top advisers met with the Egyptian delegation later that evening. It was clear that they were on the verge of leaving. “I know you are all very discouraged,” Carter said. The Sinai settlements seemed to be an insurmountable issue. “Our position is that they are illegal and should be removed,” he continued. “On this, your views and ours are the same.” He admitted that he did not have a solution. He only wanted a little more time.

“My good friend Jimmy, we have already had three long sessions,” Sadat replied. “I cannot yield conquered land to Israel, and if sovereignty is to mean anything to Egyptians, all the Israelis must leave our territory. That man Begin is not saying anything that he might not have said prior to my Jerusalem initiative.” Sadat pointed out numerous areas where he had been willing to compromise, whereas Begin “haggles over every word, and is making his withdrawal conditional on keeping land. Begin is not ready for peace.”

Carter defended Begin as “a tough and honest man.” He analyzed the situation from Begin’s perspective. “His present control over Sinai was derived from wars which Israel did not start,” Carter observed. He reminded the Egyptians of America’s special relationship with Israel and stressed that the Israelis really did want peace.

Sadat, annoyed, lit his pipe and exhaled a river of smoke from his nostrils. “It was I who made the peace initiative,” he said. “If Begin had really desired peace, we would have had it for some time now.” He said he was willing to be flexible, but not on Sinai. “I must have also a resolution of the West Bank and Gaza,” he added.

As the Americans auditioned various ideas for the discouraged Egyptians, Carter mentioned the 1972 Shanghai Communiqué, a famous document in the annals of diplomacy, which was crafted by Henry Kissinger, Richard Nixon’s national security advisor at the time, and Chou En-lai, the Chinese prime minister. Both the U.S. and China had sought to normalize relations, but they could not find a way to agree on the language that would resolve the central issue, which was China’s claim to Taiwan, an American ally. Finally, Kissinger resorted to what he later termed “constructive ambiguity,” by inserting the sentence “The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a province of China,” but avoiding the question of who should govern it. The agreement opened the way for China and the U.S. to overcome decades of hostility. As Carter explained it to the Egyptians, “We both agreed that there was one China, but we did not destroy the agreement by trying to define ‘one China’ too specifically.”

Carter might have employed another famous example of constructive ambiguity with which the delegates were more familiar: UN Resolution 242. The language that had been proposed by the Arab states and the Soviet Union demanded that Israel withdraw from “all the territories occupied during the hostilities of June 1967.” That was modified to read as just “the territories.” To further fudge the matter, the definite article was finally removed from the English-language version of the text but was retained in the French version. Since both were official UN documents, the Arabs could say that the resolution bound Israel to withdraw from the lands it had conquered and Israel could say that it agreed to withdraw from some, while not committing to which ones. Of course, finally resolving that ambiguity was one reason for the summit at Camp David.

“Stalemate here would just provide an opportunity for the most radical elements to take over in the Middle East,” Carter warned as the meeting broke up. “We simply must find a formula that Egypt and Israel can accept. If you give me a chance, I don’t intend to fail.”

It was one in the morning when Carter came to bed. For all practical purposes, the summit was over, he admitted to Rosalynn. “There must be a way,” he said, again and again. “We haven’t found it yet, but there must be a way.”

Rosalynn watched him struggle. “When Jimmy’s pondering, he gets quiet,” she noted in her memoirs, “and there’s a vein in his temple that I can see pounding. Tonight it was pounding.”

ROSALYNN HAD KNOWN Jimmy all her life; she was actually born in the house next door to his, although Jimmy’s family moved to a farm three miles away while she was still a baby. Her father, Edgar Smith, an auto mechanic, a handsome man with dark, curly hair and a prominent dimpled chin, had met Rosalynn’s mother, Allie Murray, a strikingly lovely girl, when she was still in high school and he was driving the school bus. They didn’t marry until Allie finished college, getting a teacher’s diploma from Georgia State College for Women. Eleanor Rosalynn Smith was born the next year, on August 18, 1927. Except for her three younger siblings, Rosalynn grew up very much alone. There was no movie theater or library in Plains, which had a population of about six hundred and no other girls her age. Rosalynn spent much of her time playing dolls, sewing, reading, and cutting paper dolls out of the Sears, Roebuck catalog.

Her parents were romantic in a way that other adults in Plains didn’t seem to be. When Edgar came back from working at his garage, he would whirl Allie around the kitchen and kiss her. Other parents didn’t act that way. Edgar was strict with the children, however, and they lived in awe of him. Rosalynn responded by being perfect. Her greatest infraction was “running away”—crossing the street to play with friends. Edgar would spank her and then command her not to cry. She would hold her emotions in check until she got to the outdoor privy so she could weep unseen. She couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t let her cry. She supposed he only wanted her to be strong, but she also thought that maybe he didn’t really love her. “Just having these thoughts troubled me and gave me a guilty conscience for years,” she admitted.

In 1939, her parents allowed her to go to summer camp, the first time she had ever been away from home. When she returned, she discovered the reason she had been sent away. Her father had been in the hospital for tests. He was gravely ill. Although Edgar assured Rosalynn he was going to get better, he never did. Assuming that his suffering was because of the mean thoughts she had had about him in the past, Rosalynn did everything possible to show him how much she loved him. She brushed his hair and read the Bible and detective stories to him hour after hour, even as his face grew paler and he fought for breath. In October, he called the children to his bedside. “The time has come to tell you that I can’t get well and you’re going to have to look after Mother for me,” he told them. “You are good children and I’m depending on you to be strong.” He said that he had always wanted to go to college, but hadn’t been able to. Now he instructed his wife to sell the farm if she needed money for the children’s education. His greatest sorrow was that he wasn’t going to be around to make sure they all had good lives and opportunities he didn’t have. Once again, he commanded them not to shed tears. Afterward, Rosalynn rushed to the privy to cry and cry. “My childhood really ended at that moment,” she realized. Later, critics took note of her stoicism, calling her the “Steel Magnolia,” but her childhood had hardened her to the blows that life inflicted.

Most of the medical care in Sumter County was embodied in the indomitable figure of Lillian Carter, a registered nurse, who made a practice of treating both the black and the white citizens of Plains and dared anyone to tell her different. When Edgar Smith first contracted leukemia, Miss Lillian checked on him every day, and when the end came she took Rosalynn home and let her spend the night with her daughter Ruth. Rosalynn was thirteen years old.

Rosalynn’s mother took in sewing to support her four children and her elderly father. Eventually she got a job as a postmistress. Rosalynn worked as a part-time shampooer in a beauty parlor. She helped as well with her two younger brothers, and her little sister, who was only four when their father died. At night, Allie would read the Bible to her children and assure them that God really did love them. Rosalynn had her doubts. She was haunted by the specter of an angry, vengeful God. She was an outstanding student, always getting As, and graduated as the class valedictorian and the May Queen. She prayed; she went to church practically every time the doors opened; she achieved everything her strict and pious father would have asked of her, except the one, most important thing—to keep him alive.

Rosalynn grew into an attractive young woman, but she was sober and unsmiling. She saw herself as ordinary and painfully shy. She had her mother’s wide-set eyes and high cheekbones and her father’s dimpled chin—to which was added a small scar when she fell out of a sitting-room window as a child and landed in a rose bush. Ruth Carter, who was two years younger than Rosalynn, became her best friend; and it was in Ruth’s bedroom that Rosalynn fell in love with a photograph of a young man with slicked-back hair and a dark, burning gaze that seemed full of intelligence and ambition, looking “so glamorous and out of reach.” It was Ruth’s older brother, Jimmy. Rosalynn knew him—everybody in Plains knew everybody else—but she rarely saw him. By now she was following her father’s last dictate and attending a nearby junior college, hoping to become an interior designer, and Jimmy was off at Annapolis, another universe away. The only time Rosalynn could remember speaking to him was when she bought an ice cream cone from him one summer on Main Street. The photograph in Ruth’s bedroom filled her with longing. Jimmy had escaped Plains. He had what it took. Surely her father would have approved of him.

Ruth cooked up the idea of a romance between her idolized older brother and her best friend. She would call Rosalynn whenever Jimmy came home at Christmas or during summer leave, but Rosalynn was so intimidated by the boy in the photograph that she couldn’t imagine what she would say to him. Finally, in the summer of 1945, the year the world war ended, Ruth invited Rosalynn to a picnic. Jimmy was there. He teased her about the exotic way she made her sandwich, on mismatched slices of bread, using salad dressing instead of mayonnaise. He was obviously a perfectionist. After the picnic, the Carters dropped her off at her house, and she thought to herself, “That’s that.”

Later that afternoon, after church, she was standing with friends when a car drove up and Jimmy got out. He asked if she’d like to go to a movie—a double-date with Ruth and her boyfriend. Jimmy and Rosalynn rode in the rumble seat, and on the way home, under a full moon, he kissed her. That very night he told his mother he was going to marry Rosalynn. He was twenty; she was seventeen. They were married a year later. Jimmy presented her with a manual, called A Navy Wife.

She felt liberated the moment she left Plains, although some of their early postings were dreadful. Jimmy was often at sea, leaving Rosalynn to take care of their first child, Jack. In 1948, the year the State of Israel was created, Jimmy was accepted to submarine school in New London, Connecticut. For the first time in their married life, Jimmy had regular hours. They studied Spanish and took an art class together. When Jimmy finished sub school, they got the best news: he was being posted to the USS Pomfret, based in Hawaii. Rosalynn sewed aloha shirts and took hula lessons. Jimmy learned to play the ukulele and Rosalynn would dance to “My Little Grass Shack” and “Lovely Hula Hands.” Another son, James Earl Carter III, called Chip, was born. Plains, thankfully, was very far away.

Jimmy Carter, in his Navy uniform, and Rosalynn Carter, on their wedding day, July 7, 1946, in Plains, Georgia

The submarines of the era had to surface every twenty-four hours to recharge their batteries, and during Carter’s first cruise aboard the Pomfret, as an electronics officer, the ship ran into one of the most violent storms ever to strike the Pacific Ocean. Seven ships went down that night, and the Pomfret itself was so badly battered that it was reported missing. Carter was violently sick during the tempest, but he was dutifully standing his watch in the middle of the night when a gigantic wave rolled over the ship and swept him out to sea. He floundered inside the wave in utter darkness. In an instant, he had been subtracted from the world he knew and plunged into an obscure and inky grave. Suddenly he was slammed against the five-inch gun behind the conning tower, about thirty feet from where he had been standing. He held on to the cannon with everything he had. It was eerie; no one on the ship had even known he was missing. Fortunately, Rosalynn was visiting in Plains and did not hear the false report that the ship had been lost at sea.

Being a Navy wife suited Rosalynn. She enjoyed the companionship of other wives; there were always children around for her own to play with; and the postings took them to interesting places. So when Carter’s father died in 1953, Rosalynn wasn’t at all prepared to hear that Jimmy was quitting the Navy and they were moving back to Plains. She cried and screamed. It was the most serious argument of their marriage. She refused to talk to him on the entire drive back. If she needed to stop for the restroom, she would tell Jack, and Jack would tell his dad. When they finally pulled into Plains, Jimmy turned to her with his biggest grin and said, “We’re home!” It was as if the prison doors had closed upon her and the best part of her life was over.

The first year Jimmy and Rosalynn were back in Plains there was a terrible drought; the crops failed, and their income that year was less than $200. They lived in public housing. Rosalynn took over the bookkeeping in the peanut warehouse, while Jimmy sold seed and fertilizer. The bank turned them down when Jimmy asked for a business loan. Quitting the Navy appeared to be a colossal mistake. Although they were scraping by, living on savings, they buried themselves in community work. Jimmy got involved with the Chamber of Commerce, the Hospital Authority, and the Library Board, while Rosalynn joined the PTA and the Garden Club. She was the den mother for her boys’ Cub Scout pack. The next year the rains finally came and their business began to prosper.

Jimmy was seen as somewhat exotic in Plains because of his education and his spin in the Navy. He quickly took on the role of a community leader, becoming chairman of the county school board at a time when racial integration was ripping the Deep South into bitter factions. In 1962, he tried to consolidate the three white schools in the county, but the white population saw it as a prelude to school desegregation. A homemade sign was placed in front of the Carter warehouse: COONS AND CARTERS GO TOGETHER. Carter’s initiative was voted down. As would be true at other times in his life, failure was a spur to Carter’s ambition. On the morning of his thirty-eighth birthday, he put on his Sunday pants rather than the work clothes he normally wore to the warehouse. Rosalynn asked where he was going, and he told her he was on his way to Americus, the county seat, to place a notice in the newspaper that he would be a candidate for the state senate. He had not consulted her or anyone else. The election was fifteen days away. Rosalynn was thrilled, although she had never actually met a state senator.

South Georgia in 1962 was a brutal school for political neophytes. Sumter County, where Plains is located, was the largest in Carter’s district, and he was well known there. However, Quitman County, on the Alabama state line, was ruled by a bootlegger with a reputation for disposing of his enemies in the Chattahoochee River. His name was Joe Hurst. He exercised almost total control, like a feudal lord, handing out patronage and even passing out the welfare checks for the 50 percent of the county residents who were beneficiaries. He used his fiefdom to become one of the most powerful figures in the state. For the Democratic primary, Hurst refused to set up voting booths; instead, he greeted each voter and told them how to vote—against Carter, with his clean-government agenda. Because there was no Republican candidate, the primary was tantamount to election. When one elderly couple tried to sneak their ballots into the box without Hurst’s examination, he threatened to burn down their house.

Carter was leading by 70 votes until Quitman County finally announced its results: 333 voters had somehow cast 420 votes. Some of the dead had risen from their graves to cast ballots, and more than a hundred had managed to vote in alphabetical order. Carter lost the election. He contested the results, precipitating a convulsion in state politics that wasn’t resolved until the moment he actually raised his hand and took the oath of office on the floor of the state senate in 1963. Joe Hurst sent Rosalynn a message that the last time people crossed him, their businesses burned down. Rosalynn was terrified. While Jimmy was in Atlanta during the legislative session, she left lights on in their house, pushed the couch against the door at night, slept with their children, and nailed the windows shut.

That year the civil rights movement arrived in Sumter County. Martin Luther King was arrested in Americus. Police beat protesters with billy clubs and shocked them with cattle prods. Hundreds of black marchers were arrested. A white student was killed in one of the demonstrations. Carter was quiet on the subject of race, although in his first substantive speech in the state senate, in his second legislative session, he denounced the thirty questions that were asked of blacks who were attempting to register to vote, which included abstruse matters of law, such as “What do the constitutions of the United States and Georgia provide regarding the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus?” and such nonsense as “How long is a piece of string?” or “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?” His maiden speech went unreported, however.

In the summer of 1965, Carter finally had to face a moment of truth on the race issue. There was a photograph in newspapers all over the world of a mixed group of blacks and whites praying on the steps of the First Baptist Church in Americus while the pastor stood over them with a riot gun and a bandolier of bullets across his chest, barring entry. Soon after that, a resolution was introduced in the Plains Baptist Church, where Carter was a deacon, to exclude “Negroes and other agitators.” Jimmy and Rosalynn were in Atlanta for a wedding, and she begged Jimmy not to return for the vote in the church. She was exhausted by the controversies and the boycotts of their business; moreover, Jimmy was contemplating a run for the U.S. Congress, and racial politics could easily sink him. Jimmy insisted on speaking against the measure, however. When the vote was taken, the ban passed overwhelmingly. Only six parishioners voted against it—five members of the Carter family and a deaf man who may not have understood what he was voting for.

Carter announced that he was running for the U.S. House of Representatives against Howard “Bo” Callaway, the Republican incumbent, who was a West Point graduate and the heir to a textile fortune. Callaway was popular in the state and had strong support from the extreme-right-wing John Birch Society. However, when the Democratic candidate for governor suffered a heart attack and withdrew from the race, Callaway decided to run for that office instead, leaving Carter with only token opposition for the congressional seat. Carter tried to enlist another candidate to run against Callaway in order to keep the statehouse from going Republican for the first time in a century, but finally decided to do it himself. With only three months before the primary, he dropped out of the congressional race he was nearly certain to win and entered the gubernatorial Democratic primary. His main opponents were a former governor, Ellis Arnall, thought to be too liberal to beat Callaway, and the segregationist and archconservative Lester Maddox. Rosalynn was extremely unhappy with Jimmy’s decision. It meant that they would not be moving to Washington, which she dreamed of, and that they would also be spending a large portion of their savings on a race that was going to be very difficult to win.

Carter recruited his family and a small circle of friends to travel the state and campaign for him. That included Rosalynn, who was shy and fearful of speaking in public, but she gamely drove all across the state asking people for their vote, sometimes a degrading or humiliating experience. She hated standing in front of Kmarts, for instance, which did not allow soliciting, and she suffered the indignity of being run off from nearly every Kmart in the state. In one small Georgia town she handed a brochure to a man who was standing in the doorway of a shoe shop, chewing tobacco. Rosalynn asked him to vote for her husband. The man responded by spitting on her.

Carter lost the primary by twenty thousand votes. Maddox went on to win a runoff with Arnall and then faced Callaway in the general election. Because of a write-in campaign for Arnall, neither man received a plurality, and under Georgia law the race was decided by the predominately Democratic General Assembly. Maddox became the new governor. Carter had dropped 22 pounds (down to 130), and was deeply in debt. One month later, he started campaigning for the office again.

He roamed the state, meeting people, recording their names on a pocket tape recorder, along with some personal details, such as their job, political philosophy, and likelihood of being a contributor or a worker in the campaign. He kept a running tally of how many hands he shook—600,000 by the end of the campaign. To get the addresses of people he came in contact with he bought every telephone book in Georgia—more than 150—and then Rosalynn followed up with a thank-you note. She kept his files and clipped newspaper articles for him. To save money, he stayed in the homes of his supporters. For the last two years of his second run he was away from home nearly every night.

As Rosalynn barnstormed through Georgia, she got an intimate education about the problems that her fellow citizens faced. One day at four thirty in the morning, she was standing in front of a cotton mill, waiting for the shift change, when a woman came out, her hair and sweater covered in lint from her labor during the night. Rosalynn asked if she was going home to bed. The woman said she might get a nap, but she had a mentally retarded child at home, and the expenses were more than her husband’s income so she had to work nights to make up the difference. That moment became a turning point for Rosalynn. When she realized that Jimmy was coming to the same town later that day, she stood in line to meet him. He reached for her hand before he even realized who she was. “I want to know what you are going to do about mental health when you are governor,” she said. The startled Carter replied, “We’re going to have the best mental health system in the country, and I’m going to put you in charge of it.”

On election day, 1970, Carter won 60 percent of the vote. Maddox, unable to succeed himself as governor, was elected lieutenant governor, with 73.5 percent of the vote.

Carter was seen as a rising figure in Democratic politics, but very few people understood the full scope of his ambition. He gained a reputation as a progressive governor, despite a contentious relationship with the Georgia legislature. Within two years of his election to the statehouse, he decided he would run for president. He would be out of office in 1974, which meant that he could run full-time for the following two years.

Once again, Rosalynn was making the speeches she hated so much. By the end of the presidential campaign she had visited forty-two states, and more than a hundred communities in Iowa alone. On January 20, 1977, on an icy morning in Washington, D.C., her husband was inaugurated as the thirty-ninth president of the United States, and Rosalynn Carter, the lonely little girl from Plains, became first lady. While Jimmy was taking the oath, their predecessors, Gerald and Betty Ford, stood beside them—a ritual of democracy that is perhaps the most powerful testament to the tradition of nonviolent social change. At that very moment, the closets of the White House were being emptied of the Fords’ belongings and the Carters’ clothes hung there instead.

Rosalynn proved to be an activist first lady, sponsoring significant legislation for mental health and the elderly, and upsetting many Americans by unapologetically sitting in on cabinet meetings. Those close to the president knew that she was always his most influential adviser, and they came to appreciate her political savvy. In 1979, even as Carter’s own poll numbers plummeted, Rosalynn topped Mother Teresa in Gallup’s poll for the most admired woman in the world.

Camp David had been her idea. However it turned out, she would bear both credit and responsibility.

FOREIGN MINISTER KAMEL WAS unable to sleep. He sat on the edge of his bunk talking to his roommate, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, until late at night. Camp David was a strange place to conduct diplomacy, they agreed. They were used to wearing dark suits and meeting in the marbled offices of state, and here they were in the woods in their pajamas. The main problem for the Egyptians, however, was not the setting but their leader. Whenever they met, Sadat sat silently, inscrutably puffing on his pipe, as his delegation fumed. It didn’t seem to trouble him that Carter was not interested in a single principle embodied in the Egyptian project. “And now look where we are!” Kamel exclaimed in his bunk, “Here we have the United States president, without equivocation or ambiguity, coming up with the idea of concluding a strategic American-Egyptian-Israeli alliance, while Sadat does not utter a single word! What can be the matter with him?”

“Maybe he was only absent-minded or tired,” Boutros-Ghali responded. He added, “It could be that Carter’s aim was to test us by throwing out ideas as trial balloons.”

“Didn’t you notice Carter’s sly remark to Tohamy, to the effect that rumors had it that President Sadat was moderate while his assistants were hard-liners? He means us, of course.”

“Anyway, today’s meeting was merely preparatory,” Boutros-Ghali said. “We shan’t know the conclusions they have reached until they finalize their project and submit it to us—then we shall see. So stop worrying until then and let’s get some sleep—it’s almost dawn!”