Tip #92: Proofread your essay and application materials, reviewing spelling and punctuation in light of one of the two major systems — American English or British English.

Tip #92: Proofread your essay and application materials, reviewing spelling and punctuation in light of one of the two major systems — American English or British English.Chapter 10

Packaging Your MBA Essays

and Application

A product that looks good is worth something.

—Merchant’s adage

AMERICAN ENGLISH VS. BRITISH ENGLISH — SPELLING AND PUNCTUATION

Tip #92: Proofread your essay and application materials, reviewing spelling and punctuation in light of one of the two major systems — American English or British English.

Tip #92: Proofread your essay and application materials, reviewing spelling and punctuation in light of one of the two major systems — American English or British English.

American English and British English are the two major engines behind the evolving English language. Other English-speaking countries — most notably Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, the Philippines, and South Africa — embrace a variant of one or both of these two major systems. Although American and British English do not differ with respect to grammar per se, each system has its own peculiarities in terms of spelling and punctuation. The purpose of the following material is to provide a snapshot of these differences.

SPELLING DIFFERENCES:

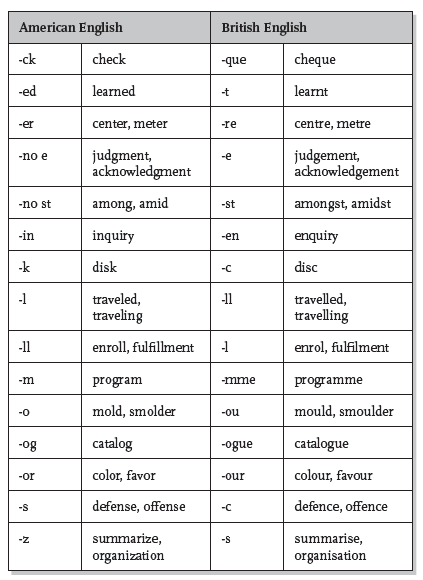

Generally, the place of your undergraduate institution will determine whether you are writing an application and adhering to spelling and punctuation conventions consistent with American or British English. For example, if you attended Cambridge University, you’ll in all likelihood be spelling words according to British English (e.g., “summarise,” “favour,” and “travelling”). If you attended Boston University, you’ll be spelling words according to American English (e.g., “summarize,” “favor,” and “traveling”). Exhibit 10.1 contains a summary of the major spelling differences. Try not to commingle the systems. Stick to one system to achieve consistency.

The following summary encapsulates some the nuances between British and American spelling:

The British generally double the final -l when adding suffices that begin with a vowel, where Americans double it only on stressed syllables. This makes sense given that American English treats -l the same as other final consonants, whereas British English treats it as an exception. For example, whereas Americans spell counselor, equaling, modeling, quarreled, signaling, traveled, and tranquility, the British spell counsellor, equalling, modelling, quarrelled, signalling, travelled, and tranquillity.

Certain words — compelled, excelling, propelled, and rebelling — are spelled the same on both platforms, consistent with the fact that the British double the -l while Americans observe the stress on the second syllable. The British also use a single -l before suffixes beginning with a consonant, whereas Americans use a double -l. Thus, the British spell enrolment, fulfilment, instalment, and skilful, Americans spell enrollment, fulfillment, installment, and skillful.

Deciding which nouns and verbs end in -ce or -se is understandably confusing. In general, nouns in British English are spelled -ce (e.g., defence, offence, pretence) while nouns in American English are spelled -se (e.g., defense, offense, pretense). Moreover, American and British English retain the noun-verb distinction in which the noun is spelled with -ce and the core verb is spelled with an -se. Examples include: advice (noun), advise (verb), advising (verb) and device (noun), devise (verb), devising (verb).

With respect to licence and practice, the British uphold the noun-verb distinction for both words: licence (noun), license (verb), licensing (verb) and practice (noun), practise (verb), practising (verb). Americans, however, spell license with an -s across the board: license (noun), license (verb), licensing (verb), although licence is an accepted variant spelling for the noun form. Americans further spell practice with a -c on all accounts: practice (noun), practice (verb), practicing (verb).

Exhibit 10.1 – Spelling Differences Between American English and British English

PUNCTUATION DIFFERENCES:

The following serves to highlight some of major differences in punctuation between America English and British English.

Abbreviations

American English

Mr. / Mrs. / Ms.

British English

Mr / Mrs / Ms

Americans use a period (full stop) after salutations; the British do not.

American English

Nadal vs. Federer

British English

Nadal v. Federer

Americans use “vs.” for versus; the British write “v.” for versus. Note that Americans also use the abbreviation v. in legal contexts. For example, Gideon v. Wainright.

Colons

American English

We found the place easily: Your directions were perfect.

British English

We found the place easily: your directions were perfect.

Americans often capitalize the first word after a colon, if what follows is a complete sentence. The British prefer not to capitalize the first word that follows the colon, even if what follows is a full sentence.

Commas

American English

She likes the sun, sand, and sea.

British English

She likes the sun, sand and sea.

Americans use a comma before the “and” or “or” when listing a series of items. The British do not use a comma before the “and” when listing a series of items.

American English

In contact sports (e.g., American football and rugby) physical strength and weight are of obvious advantage.

British English

In contact sports (e.g. American football and rugby) physical strength and weight are of obvious advantage.

The abbreviation “i.e.” stands for “that is”; the abbreviation “e.g.” stands for “for example.” In American English, a comma always follows the second period in each abbreviation (when the abbreviation is used in context). In British English, a comma is never used after the second period in either abbreviation.

Note that under both systems, these abbreviations are constructed with two periods, one after each letter. The following variant forms are not correct under either system: “eg.,” or “eg.” or “ie.,” or “ie.”

Dashes

American English

The University of Bologna – the oldest university in the Western World – awarded its first degree in 1088.

British English

The University of Bologna - the oldest university in the Western World - awarded its first degree in 1088.

The British have traditionally favored the use of a hyphen where Americans have favored the use of the dash. Discussion of the two types of dashes is found in both upcoming segments: Using Readability Tools and Editing Tune-ups.

Quotation Marks

American English

Some see education as a “vessel to be filled,” others see it as a “fire to be lit.”

British English

Some see education as a ‘vessel to be filled’, others see it as a ‘fire to be lit’.

Americans use double quotation marks. The British typically use single quotation marks.

American English

Our boss said, “The customer is never wrong.”

Or: “The customer is never wrong,” our boss said.

British English

Our boss said, ‘The customer is never wrong.’

Or: ‘The customer is never wrong,’ our boss said.

Periods and commas are placed inside quotation marks in American English (almost without exception). In British English, the treatment is twofold. Punctuation goes inside quotation marks if it’s part of the quote itself; if not, quotation marks go on the outside. This means that in British English periods and commas go on the outside of quotation marks in all situations not involving dialogue or direct speech. However, in situations involving direct speech, periods and commas generally go inside of quotation marks because they are deemed to be part of the dialogue itself.

NOTE  Today, the practice of using single quotation marks is not ubiquitous in the United Kingdom. A number of UK-based newspapers, publishers, and media companies now follow the practice of using double quotation marks.

Today, the practice of using single quotation marks is not ubiquitous in the United Kingdom. A number of UK-based newspapers, publishers, and media companies now follow the practice of using double quotation marks.

USING READABILITY TOOLS

Tip #93: Review documents for effective use of readability tools: bolds, bullets, dashes, enumeration, headings and headlines, indentation, italics, and short sentences. Look to apply edit touch-ups and check for grammatical gremlins (diction).

Tip #93: Review documents for effective use of readability tools: bolds, bullets, dashes, enumeration, headings and headlines, indentation, italics, and short sentences. Look to apply edit touch-ups and check for grammatical gremlins (diction).

Bolds

Bolds may be used to emphasize key words or phrases or aid in dividing an essay into parts. Bolding the occasional key word causes words to jump out at the reader, making the job of reading your writing easier. Underlining or capitalizing does basically the same job as bolding. Underlining is a carryover from the days of the typewriters when bolding was not an option. With the advent of word processing, bolding and italics have taken over. Be careful not to overuse bolding. You will not only dull the effect but also risk patronizing the reader. Moreover, remember an unwritten rule of publishing: Never use bolds, full caps, and underlining at the same time.

Bullets

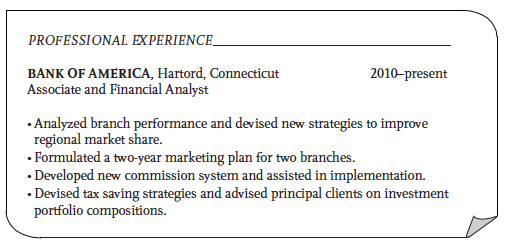

Bullets are effective tools when paraphrasing information. They are excellent for presenting information in short phrases when formal sentences are not required. Bullets are de rigueur for use in PowerPoint® presentations or flyers. In business school presentations, bullets (either square or circular) are commonly used in résumés or employment records and/or when presenting extracurricular activities. Bullets are not, however, recommended for use in the body of your essays. It is not considered good practice in formal writing to use hyphens (-) or asterisks (*) in place of bullets.

Résumé Excerpt:

Dashes

Dashes can be used to vary the rhythm of a sentence, and to present ideas with a bit of flair. The use of the dash is considered more dramatic compared with the comma.

Dartmouth College, the world’s oldest business school program, awarded its first MBA degree in 1900.

or

Dartmouth College – the world’s oldest business school program – awarded its first MBA degree in 1900.

Enumeration

Enumerations involve the numbering of points. Listing items by number is more formal but very useful for ordering data. Note that the words “first,” “second,” and “third” may also function in a similar manner.

Essay excerpt

Given time constraints, I see three potential scenarios that would overcome such an impasse. I would play a different role in each scenario to facilitate timely competition. The three scenarios are:

i) We have the same solution.

ii) We have different solutions.

iii) We have no solution at all.

Essay excerpt

I feel that my greatest long-term contributions working in this field will be measured by: (1) my ability to find ways to define and quantify, in “dollars and cents” terms, the benefits of ethics and corporate citizenship, and (2) my ability to sell corporations on the proactive benefits of these programs as a means to market the company, products and employees.

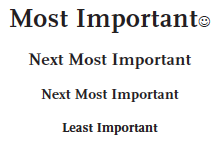

Headings and Headlines

Headings and headlines may be especially useful in writing essays for business school, as both devices help the reader obtain information very quickly. Headings and headlines are similar devices; the difference lies in their length and purpose. Headings are usually a word or two in length; headlines are usually several words in length, and may even be a line or two in length. The purpose of headings is to divide information under sections. The primary purpose of headlines is to summarize or paraphrase information, especially to capture the reader’s attention. As an example, consider a short article about buying diamonds, centered on the four C’s. Predictable headings would include “Color,” “Clarity,” “Cut,” and “Carat Weight.” The same article might instead employ the following headlines: “Less color, more desirable,” “Fewer inclusions, greater value,” “Better cut, better sparkle,” and “More carats, more the merrier.”

Headlines are used in the “Disney” essay written by Shannon (Chapter 3). Through the use of the six caption headings — Is your watch accurate? … The dial of creativity … The gears of teamwork … The strap of humanity … The hands of direction … The case of leadership … The complete watch — we gain a hint of what is being discussed in each section. For more on headlines, refer to tip #49 in Chapter 4.

Indentation

Two basic formats may be followed when laying out a written document: “block-paragraph” format and “indented-paragraph” format. The block-paragraph format typifies the layout of the modern business letter. Each paragraph is followed by a single line space (one blank line). Paragraphs are blocked, meaning that every line aligns with the left-hand margin with no indentation. Often, paragraphs are fully justified, which means there are no “ragged edges” on the right-hand side of any paragraph. The indented-paragraph format is the layout followed in a novel. The first line of each paragraph is indented and there is no line space used between paragraphs within a given section.

This book employs both layout formats. The basic text follows the block-paragraph format while the sample essays included in Chapters 3, 4, and 5 follow the indented-story format. For the purposes of writing business school essays, the most commonly followed format for online business school essays is the block-paragraph format.

Italics

Italics, like bolds, serve similar purposes. Think of using italics to highlight certain key words, especially those of contrast or illustration. For example, words of illustration commonly include: first, second, and third. Two obvious words of contrast include “no” and “not.” Be careful of overusing italics, because they are tiring on the eye and will make the page look unduly busy.

I grew up understanding work as the act of filling a position, not as a career that should be strategized and planned.

Short Sentences

There is power in short sentences and you should concentrate on using a few of these in your essays. Short sentences catch the eye and stand as if “bare naked” in front of the reader.

I like beer. Beer explains more about me than anything in the world. Who am I? I am the beer man – at least that is what many of my close friends call me.

One tip that has some merit is the “topic sentence, one-line rule.” Topic sentences are effectively the first sentence of each paragraph you write. The practice of trying to keep most of your topic sentences to a single typed line in length will make it easier for the reader to grasp the main ideas in each of your paragraphs.

EDITING TOUCH-UPS

Abbreviations (Latin)

The abbreviations “e.g.” (meaning “for example”) and “i.e.” (meaning “that is”) are constructed with two periods, one after each of the two letters, with a comma always following the second period. The forms “eg.” or “ie.” are not correct.

Below are three ways to present information using “for example.”

Correct: A number of visually vibrant colors (e.g., orange, pink, and purple) are not colors that would normally be used to paint the walls of your home.

Correct: A number of visually vibrant colors, e.g., orange, pink, and purple, are not colors that would normally be used to paint the walls of your home.

Correct: A number of visually vibrant colors, for example, orange, pink, and purple, are not colors that would normally be used to paint the walls of your home.

Below are three ways to present information using “that is.”

Correct: The world’s two most populous continents (i.e., Asia and Africa) account for 75 percent of the world’s population.

Correct: The world’s two most populous continents, i.e., Asia and Africa, account for 75 percent of the world’s population.

Correct: The world’s two most populous continents, that is, Asia and Africa, account for 75 percent of the world’s population.

The Latin abbreviations as listed in Exhibit 10.2 should be used with caution. Their use depends on whether the intended audience is likely to be familiar with their meaning. This compilation is not so much an endorsement for their use as it is a convenient list in case readers find them in various works.

Exhibit 10.2 – Latin Abbreviations and Their Meaning

NOTE  The abbreviation “etc.” stands for “et cetera” and translates as “and so forth.” Never write “and etc.” because “and” is redundant and otherwise reads “and and so forth.”

The abbreviation “etc.” stands for “et cetera” and translates as “and so forth.” Never write “and etc.” because “and” is redundant and otherwise reads “and and so forth.”

Brevity

As a general rule, less is more. Consider options that express the same ideas in fewer words without changing the meaning of a sentence.

Less effective: A movie director’s skill, training, and technical ability cannot make up for a poor script.

More effective: A movie director’s skill cannot make up for a poor script.

Often you can cut “of” or “of the.”

Original: employees of the company

Better: company employees

Don’t use “due to the fact that” or “owing to the fact that.” Use “because” or “since.”

Original: Owing to the fact that questionnaires are incomplete, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Better: Because questionnaires are incomplete, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Original: We want to hire the second candidate due to the fact that he is humorous and has many good ideas.

Better: We want to hire the second candidate since he is humorous and has many good ideas.

Colon

A colon (a punctuation mark that consists of two vertical dots) is commonly used to introduce a list or series of items and is often used after, or immediately after, the words “follow(s),” “following,” “include(s),” or “including.” A colon is not used after the words namely, for example, for instance, or such as. When introducing a list or series of items, a colon is also not used after forms of the verb “to be” (i.e., is, are, am, was, were, have been, had been, being) or after “short” prepositions (e.g., at, by, in, of, on, to, up, for, off, out, with).

Incorrect: We sampled several popular cheeses, namely: Gruyere, Brie, Camembert, Roquefort, and Stilton.

(Remove the colon placed after the word “namely.”)

Incorrect: My favorite video game publishers are: Nintendo, Activision, and Ubisoft.

(Remove the colon placed after the verb “are.”)

Incorrect: Graphic designers should be proficient at: Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, and Adobe Acrobat.

(Remove the colon placed after the preposition “at.”)

However, if what follows a colon is not a list or series of items, the writer is free to use the colon after any word that he or she deems fit.

Correct: The point is: People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.

(A colon follows the verb “is.”)

Correct: Warren Buffett went on: “Only four things really count when making an investment — a business you understand, favorable long-term economics, able and trustworthy management, and a sensible price tag. That’s investment. Everything else is speculation.”

(A colon follows the preposition “on.”)

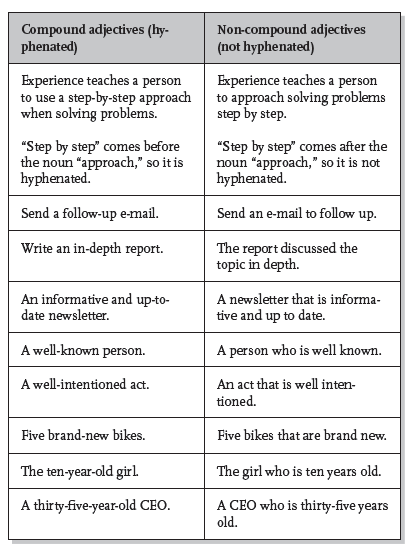

Compound adjectives

Compound adjectives (also called compound modifiers) occur when two (or more) words act as a unit to modify a single noun. As illustrated in Exhibit 10.3, use a hyphen to join the compound adjective when it comes before the noun it modifies, but not when it comes after the noun.

Note that in situations where compound adjectives are formed using multiple words and/or words that are already hyphenated, it is common practice to use an en dash (–) to separate them. See entry under Dashes.

Example: Los Angeles–Buenos Aires

Example: quasi-public–quasi-private health care bill

Sometimes compound adjectives consist of a string of “manufactured” words.

Example: a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants entrepreneur

Example: a tell-it-like-it-is kind of spokesperson

There are four potentially confusing situations where compound adjectives are either not formed or not hyphenated. The first occurs where a noun is being modified by an adjective and an adjective is being modified by an adverb.

Example: very big poster

In the previous example, “big” functions as an adjective describing the noun “poster,” and “very” functions as an adverb describing the adjective “big.”

The second situation occurs when adjectives describe a compound noun: that is, two words that function as a single noun.

Example: cold roast beef

Here the word “cold” functions as an adjective to describe the compound noun “roast beef.” We would not write “cold-roast beef” because “cold-roast” does not jointly modify “beef.”

Example: little used book

Here the word “little” functions as an adjective to describe the compound noun “used book.” The meaning here is that the book is not new and also little. However, it would also be correct to write “little-used book” if our intended meaning was that the book was not often referred to.

A third situation occurs when a compound noun describes another noun.

Example: high school student

Example: cost accounting issues

Exhibit 10.3 – Compound Adjectives

“High school” is considered a compound noun that describes “student.” Compound nouns are not hyphenated. “Cost accounting,” which describes “issues,” is also a non-hyphenated compound noun.

A fourth situation occurs when compounds are formed with adverbs ending in “ly.” Adverbs ending in “ly” are not hyphenated, even when functioning as compound modifiers.

Example: a highly motivated employee

Example: a newly published magazine

Example: a publicly traded company

Example: a frequently made error

NOTE  “Family-owned” and “family-run” are hyphenated (when functioning as compound adjectives) because “family,” although ending in “ly,” is not an adverb.

“Family-owned” and “family-run” are hyphenated (when functioning as compound adjectives) because “family,” although ending in “ly,” is not an adverb.

Dashes

Note first the difference between a hyphen and a dash. A dash is longer than a hyphen (-) and should not be used when what is needed is a dash. There are two types of dashes. The first is called “em dash” (“—”), which is the longer of the two dashes. The second is called “en dash” (“–”), which is the shorter of the two dashes. The en dash (–) is most popular in everyday writing, while the em dash (—) is the standard convention for formal published documents. Incidentally, the en dash is so-called because it is the width of the capital letter “N”; the em dash is so-called because it is the width of the capital letter “M.” These two types of dashes can be found in Microsoft Word® under the pull-down menu Insert, Symbols, Special Characters.

Three common conventions arise relating to the use of the dash: (1) an en dash (“ – ”) with spaces on both sides of the dash, (2) an em dash (“–”) with no spaces on either side of the dash, and (3) an em dash (“ — ”) with spaces on both sides of the dash. The first two conventions are the most popular for written (non-published) documents. The third option is popular on websites.

Example: To search for wealth or wisdom – that’s a classic dilemma.

(Spaces on both sides of the en dash.)

Example: To search for wealth or wisdom—that’s a classic dilemma.

(No space on either side of the em dash.)

Example: To search for wealth or wisdom — that’s a classic dilemma.

(Space on both sides of the em dash.)

Hyphen

Use a hyphen with compound numbers between twenty-one through ninety-nine and with fractions.

Example: Sixty-five students constitute a majority.

Example: A two-thirds vote is necessary to pass.

In general, use a hyphen to separate component parts of a word in order to avoid confusion with other words especially in the case of a double vowel.

Example: Our goal must be to re-establish dialogue, then to re-evaluate our mission.

Example: Samantha’s hobby business is turning shell-like ornaments into jewelry.

Use a hyphen to separate a series of words having a common base that is not repeated.

Example: small- to medium-sized companies

(This of course is the shortened version of “small-sized to medium-sized companies.”)

Example: short-, mid-, and long-term goals

(This is the shortened version of “short-term, mid-term, and long-term goals.”)

In general, use hyphens with the prefixes ex- and self- and in forming compound words with vice- and elect-.

Example: Our current vice-chancellor, an ex-commander, is a self-made man.

NOTE  “Vice president” (American English) is not hyphenated, but “vice-presidential duties” is.

“Vice president” (American English) is not hyphenated, but “vice-presidential duties” is.

Modification errors

Watch for those modification errors that occur when a phrase or clause beginning a sentence (typically set off by a comma) is separated from the word it is intended to modify. Modifying words or phrases should be kept close to the words they modify.

Original: In addition to building organizational skills, the summer internship also helped me hone my team-building skills.

(Who is building organizational skills? According to this original sentence, “the summer internship” is the person who is doing the building.)

Correct: In addition to building organizational skills, I also honed my team-building skills during the summer internship.

Original: Recognizing the value of each person’s input, our group’s decision was made only after discussing the ideas of all members.

(Who recognizes the value of each person’s input? According to this original sentence, “our group’s decision” does.)

Correct: Recognizing the value of each person’s input, we discussed the ideas of all members before making our decision.

Nominalizations

A guiding rule of style is that we should prefer verbs (and adjectives) to nouns. Verbs are considered more powerful than nouns. In other words, a general rule in grammar is that we shouldn’t change verbs (or adjectives) into nouns. The technical name for this no-no is “nominalization”; we shouldn’t nominalize.

Avoid changing verbs into nouns:

More effective: reduce costs

Less effective: reduction of costs

More effective: develop a five-year plan

Less effective: development of a five-year plan

More effective: rely on the data

Less effective: reliability of the data

In the above three examples, the more effective versions represent verbs, not nouns. So “reduction of costs” is best written “reduce costs,” “development of a five-year plan” is best written “develop a five-year plan,” and “reliability of the data” is best written “rely on the data.”

Avoid changing adjectives into nouns:

More effective: precise instruments

Less effective: precision of the instruments

More effective: creative individuals

Less effective: creativity of individuals

More effective: reasonable working hours

Less effective: reasonableness of the working hours

In the latter three examples above, the more effective versions represent adjectives, not nouns. So “precision of instruments” is best written “precise instruments,” “creativity of individuals” is best written “creative individuals,” and “reasonableness of the working hours” is best written “reasonable working hours.”

Numbers

The numbers one through one hundred, as well as any number beginning a sentence, are spelled out. Numbers above 100 are written as numerals (e.g., 101).

Original: Our professor has lived in 3 countries and speaks 4 languages.

Correct: Our professor has lived in three countries and speaks four languages.

Passive voice vs. active voice

As a general rule of style, write in the active voice, not in the passive voice (all things being equal).

Less effective: Sally was loved by Harry.

More effective: Harry loved Sally.

Less effective: In pre-modern times, medical surgery was often performed by inexperienced and ill-equipped practitioners.

More effective: In pre-modern times, inexperienced and ill-equipped practitioners often performed medical surgery.

In a normal subject-verb-object sentence, the doer of the action appears at the front of the sentence while the receiver of the action appears at the back of the sentence. Passive sentences are less direct because they reverse the normal subject-verb-object sentence order; the receiver of the action becomes the subject of the sentence and the doer of the action becomes the object of the sentence. Passive sentences may also fail to mention the doer of the action.

Less effective: Errors were found in the report.

More effective: The report contained errors.

or: The reviewer found errors in the report.

Less effective: Red Cross volunteers should be generously praised for their efforts.

More effective: Citizens should generously praise Red Cross volunteers for their efforts.

or: We should generously praise Red Cross volunteers for their efforts.

How can we recognize a passive sentence? Here’s a quick list of six words that signal a passive sentence: be, by, was, were, been, and being. For the record, “by” is a preposition, not a verb form, but it frequently appears in sentences that are passive.

Plural nouns

Watch for situations involving the personal pronouns “they” and “our” that require that they be matched with plural nouns, not singular nouns. This occurs when a noun is not identical for all members of a group. “Our dream” and “our dreams” pose different meanings.

Incorrect: Candidates should bring their résumé to their job interview.

Correct: Candidates should bring their résumés to their job interviews.

Incorrect: When it comes to computers, some people don’t have a technical bone in their body.

Correct: When it comes to computers, some people don’t have a technical bone in their bodies.

Possessives

Confusion can arise regarding how to create possessives with respect to nouns. There are four basic situations. These involve (1) creating possessives with respect to single nouns not ending in “s”; (2) creating possessives with respect to single nouns ending in “s”; (3) creating possessives for plural nouns not ending in “s”; and (4) creating possessives for plurals ending in “s.”

For single nouns not ending in the letter “s,” we simply add an apostrophe and the letter “s” (i.e., ’s).

Example: Jeff’s bike

Example: The child’s baseball glove

For single nouns ending in the letter “s,” we have a choice of either adding an apostrophe and the letter “s” (i.e., ’s) or simply an apostrophe.

Example: Professor Russ’s lecture

Example: Professor Russ’ lecture

For plural nouns not ending in the letter “s,” we simply add an apostrophe and the letter “s” (i.e., ’s).

Example: men’s shoes

Example: children’s department

For plural nouns ending in the letter “s,” we simply add an apostrophe. Note that most plural nouns do end in the letter “s.”

Example: ladies’ hats

Example: The boys’ baseball bats

In this latter example, “boys’ baseball bats” indicates that a number of boys have a number of (different) baseball bats. If we were to write “boys’ baseball bat,” it would indicate that a number of boys all own or share the same baseball bat. If we wrote “the boy’s baseball bat,” only one boy would own the baseball bat. In writing “the boy’s baseball bats,” we state that one boy possesses several baseball bats.

Print out to edit

Do not perform final edits on screen. Print documents out and edit from a hard copy.

Qualifiers

Whenever possible, clean out qualifiers, including: a bit, a little, fairly, highly, just, kind of, most, mostly, pretty, quite, rather, really, slightly, so, still, somewhat, sort of, very, and truly.

Original: Our salespeople are just not authorized to give discounts.

Better: Our salespeople are not authorized to give discounts.

Original: That’s quite a big improvement.

Better: That’s a big improvement.

Original: Working in Reykjavik was a most unique experience.

Better: Working in Reykjavik was a unique experience.

NOTE  Unique means “one of a kind.” Something cannot be somewhat unique, rather unique, quite unique, very unique, or most unique, but it can be rare, odd, or unusual.

Unique means “one of a kind.” Something cannot be somewhat unique, rather unique, quite unique, very unique, or most unique, but it can be rare, odd, or unusual.

Quotations

The following four patterns are most commonly encountered when dealing with quotations.

Example: My grandmother said, “An old picture is like a precious coin.”

Example: “An old picture is like a precious coin,” my grandmother said.

(A comma is generally used to separate the quote from regular text.)

Example “An old picture,” my grandmother said, “is like a precious coin.”

(Above is what is known as an interrupted or split quote. The lower case “i” in the word “is” indicates that the quote is still continuing.)

Example “They’re like precious coins,” my grandmother said. “Cherish all your old pictures.”

(Above are two complete but separate quotes. Note the word “cherish” is capitalized because it begins a new quote.)

With respect to American English, there is a punctuation “tall tale” that suggests using double quotation marks when quoting an entire sentence, but using single quotation marks for individual words and phrases. There is, however, no authoritative support for this practice. The only possible use for single quotation marks in American English is for a quote within a quote. For more on the use of double or single quotation marks, refer back to American English vs. British English — Spelling and Punctuation Differences.

Redundancies

Delete redundancies. Examples: Instead of writing “continued on,” write “continued.” Rather than writing “join together,” write “join.” Instead of writing “serious disaster,” write “disaster.” Rather than writing “tall skyscrapers,” write “skyscrapers.” Instead of writing “past history,” write “history.”

Run-on sentence

A run-on sentence refers to two sentences that are inappropriately joined together, usually by a comma. There are effectively four ways to correct a run-on sentence as seen in each of the four correct examples below. First, join the two sentences with a period. Second, join the two sentences with a coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, or, nor, for, yet). Third, join the two sentences with a semi-colon. Fourth, turn one of the two sentences into a subordinate clause.

Original: Technology has made our lives more comfortable, it has also made our lives more complicated.

Correct: Technology has made our lives more comfortable. It has also made our lives more complicated.

Correct: Technology has made our lives more comfortable, but it has also made our lives more complicated.

Correct: Technology has made our lives more comfortable; it has also made our lives more complicated.

Correct: Although technology has made our lives more comfortable, it has also made our lives more complicated.

Sentence fragment

A sentence fragment is a group of words that cannot stand on their own as a complete thought.

Original: A fine day indeed.

(This statement is a fragment, does not constitute a complete thought, and cannot stand on its own.)

Correct: Today is a fine day indeed.

(The sentence can be corrected by adding the subject “today” and the verb “is.”)

Sentence fragments are not acceptable for use in formal writing, e.g., essays and reports. In contrast, sentence fragments are commonly used in informal writing situations (e.g., e-mail and text messaging), and frequently seen in creative communications such as advertising, fiction writing, and poetry.

The following sentence fragments would be acceptable in informal written communication:

Will Michael Phelps’ feat of eight Olympic gold medals ever be equaled? Never.

We need to bring education to the world. But how?

Dream on! No one beats Brazil when its star forwards show up to play.

Sentence openers

Can we begin sentences with the conjunctions “and” or “but”? There is a grammar folk tale that says we shouldn’t begin sentences with either of these two words, but, in fact, it is both common and accepted practice in standard written English to do so. Most writers and journalists have embraced the additional variety gained from opening sentences in this manner. It is also acceptable to begin sentences with “because.” In the same way that the words “as” and “since” are often used to begin sentences, the word “because,” when likewise functioning as a subordinating conjunction, may also be used to begin sentences.

Slashes

A slash (also known as a virgule) is commonly used to separate alternatives. No space should be used on either side of the slash; the slash remains “sandwiched between letters.”

Incorrect: At a minimum, a résumé or CV should contain a person’s job responsibilities and / or job accomplishments.

Correct: At a minimum, a résumé or CV should contain a person’s job responsibilities and/or job accomplishments.

Space: Break up long paragraphs

Avoid long paragraphs in succession. Break them up whenever possible. This applies to e-mails as well. Often it is best to begin an e-mail with a one- or two-sentence opener before expounding on details in subsequent paragraphs.

Space: Never two spaces after periods

Avoid placing two spaces after a period (ending a sentence). Use one space. Computers automatically “build in” proper spacing. Leaving two spaces is a carryover from the days of the typewriter.

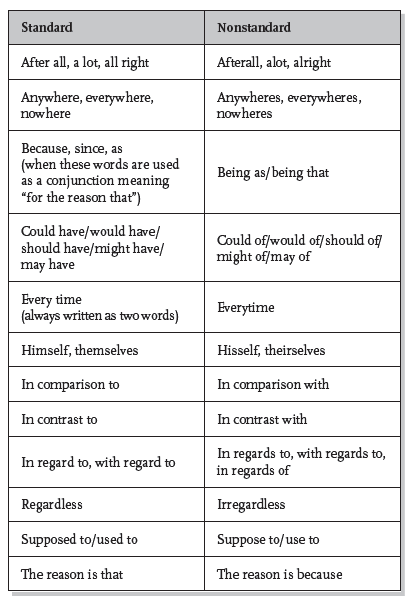

Standard vs. nonstandard words and phrases

Because language changes over time, complete agreement never exists as to what grammatical words and phrases are considered standard. From one grammar handbook to another and from one dictionary to another, slight variations arise. These differences are due in large part to the differences between colloquial and formal written language. For example, in colloquial written English, the words “all right” and “alright” as well as “different from” and “different than” are used interchangeably. Lexicographers continue to have difficulty deciding whether to prescribe language or describe it. Should they prescribe and dictate what are the correct forms of language, or should they describe and record language as it is used by a majority of people? Exhibit 10.4, on the following page, provides common misusages to watch for.

Exhibit 10.4 – Standard vs. Nonstandard Usages

Weak openers

Limit the frequent use of sentences which begin with "it is," "there is," "there are," and "there were." These constructions create weak openers. A sound practice is to never begin the first sentence of a paragraph (i.e., the opening sentence) with this type of construction.

Original: It is obvious that dogs make better pets than hamsters.

Better: Dogs make better pets than hamsters.

Original: There is an excellent chance that a better diet will make you feel better.

Better: A better diet will make you feel better.

GRAMMATICAL GREMLINS (DICTION)

Affect, Effect

Affect is a verb meaning “to influence.” Effect is a noun meaning “result.” Effect is also a verb meaning “to bring about.”

The change in company policy will not affect our pay.

The long-term effect of space travel is not yet known.

A good mentor seeks to effect positive change.

Afterward, Afterwards

These words are interchangeable: afterward is more commonly used in America while afterwards is more commonly used in Britain. A given document should show consistent treatment.

Allot, Alot, A lot

Allot is a verb meaning “to distribute” or “to apportion.” Alot is not a word in the English language, but a common misspelling. A lot means “many.”

To become proficient at yoga one must allot twenty minutes a day to practice.

Having a lot of free time is always a luxury.

All ready, Already

All ready means “entirely ready” or “prepared.” Already means “before or previously,” but may also mean “now or soon.”

Contingency plans ensure we are all ready in case the unexpected happens. (entirely ready or prepared)

We’ve already tried the newest brand. (before or previously)

Is it lunchtime already? (now or so soon)

All together, Altogether

All together means “in one group.” Altogether has two meanings. It can mean “completely,” “wholly,” or “entirely.” It can also mean “in total.”

Those going camping must be all together before they can board the bus.

The recommendation is altogether wrong.

There are six rooms altogether.

NOTE  The phrase “putting it all together” (four words) is correct. It means “putting it all in one place.” The phrase “putting it altogether” (three words) is incorrect because it would effectively mean, “putting it completely” or “putting it in total.”

The phrase “putting it all together” (four words) is correct. It means “putting it all in one place.” The phrase “putting it altogether” (three words) is incorrect because it would effectively mean, “putting it completely” or “putting it in total.”

Among, Amongst

These words are interchangeable: among is American English while amongst is British English. A given document should show consistent treatment.

Anymore, Any more

These words are not interchangeable. Anymore means “from this point forward.” Any more refers to an unspecified additional amount.

I’m not going to dwell on this mishap anymore.

Are there any more tickets left?

Anyone, Any one

These words are not interchangeable. Anyone means “any person” whereas any one means “any single person, item, or thing.”

Anyone can take the exam.

Any one of these green vegetables is good for you.

Anytime, Any time

These words are not necessarily interchangeable. Anytime is best thought of as an adverb which refers to “an unspecified period of time.” Any time is an adjective-noun combination which means “an amount of time.” Also, any time is always written as two words when it is preceded by the preposition “at”; in that case, its meaning is the same as its single word compatriot.

Call me anytime and we’ll do lunch.

This weekend, I won’t have any time to tweet (twitter).

At any time of the day, you can hear traffic if your window is open.

Anyway, Any way

These words are not interchangeable. Anyway means “nevertheless, no matter what the situation is” or “in any case, no matter what.” Any way means “any method or means.”

Keep the printer. I wasn’t using it anyway.

Is there any way of salvaging this umbrella?

NOTE  The word “anyways,” previously considered nonstandard, is now considered an acceptable variant of “anyway,” according to the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary.

The word “anyways,” previously considered nonstandard, is now considered an acceptable variant of “anyway,” according to the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary.

Apart, A part

These words are not interchangeable. Apart means “in separate pieces.” A part means “a single piece or component.”

Overhaul the machine by first taking it apart.

Every childhood memory is a part of our collective memory.

Awhile, A while

These words are not interchangeable. Awhile is an adverb meaning “for a short time.” A while is a noun phrase meaning “some time” and is usually preceded by “for.”

Let’s wait awhile.

I’m going to be gone for a while.

NOTE  It is not correct to write: “Let’s wait for awhile.”

It is not correct to write: “Let’s wait for awhile.”

As, Because, Since

These three words, when used as a conjunction meaning “for the reason that,” are all interchangeable.

As everyone knows how to swim, let’s go snorkeling.

Because all the youngsters had fishing rods, they went fishing.

Since we have firewood, we’ll make a bonfire.

Assure, Ensure, Insure

Assure is to inform positively. Insure is to arrange for financial payment in the case of loss. Both ensure and insure are now largely interchangeable in the sense of “to make certain.” Ensure, however, implies a kind of virtual guarantee. Insure implies the taking of precautionary or preventative measures.

Don’t worry. I assure you I’ll be there by 8 a.m.

When shipping valuable antiques, a sender must insure any piece for its market value in the event it’s damaged or lost.

Hard work is the best way to ensure success regardless of the endeavor.

Every large jewelry shop maintains an on-site safe to insure that inventory is secure during closing hours. (taking of precautionary measures)

Because of, Due to, Owing to

These word pairings are interchangeable and mean “as a result of.”

The climate is warming because of fossil fuel emissions.

Fossil fuel emissions are increasing due to industrialization.

Owing to global warming, the weather is less predictable.

Better, Best

Better is used when comparing two things. Best is used when comparing three or more things.

Comparing Dan with Joe, Joe is the better cyclist.

Tina is the best student in the class.

Between, Among

Use between to discuss two things. Use among to discuss three or more things.

The jackpot was divided between two winners.

Five plaintiffs were among the recipients of a cash settlement.

Cannot, Can not

These words are interchangeable with “cannot” being by far the most popular written expression in both American and British English.

Choose, Choosing, Chose, Chosen

Choose is present tense of the verb (rhymes with “blues”). Choosing is the present participle (rhymes with “cruising”). Chose is the past tense (rhymes with “blows”). Chosen is the past participle.

My plan was to choose blue or green for my company logo.

I ended up choosing teal, which is a blend of both colors.

Actually, we first chose turquoise but, soon after, realized that the shade we had chosen was a bit too bright.

NOTE  There is no such word as “chosing.” This word is sometimes mistaken for, and incorrectly used in place of, the present participle “choosing.”

There is no such word as “chosing.” This word is sometimes mistaken for, and incorrectly used in place of, the present participle “choosing.”

Complement, Compliment

Both complement or compliment can be used as nouns or verbs. As a verb, complement means “to fill in,” “to complete,” or “to add to and make better”; as a noun it means “something that completes” or “something that improves.” Compliment is used in two related ways. It is either “an expression of praise” (noun) or is used “to express praise” (verb).

A visit to the Greek islands is a perfect complement to any tour of bustling Athens. Visitors to the Greek island of Mykonos, for instance, are always struck by how the blue ocean complements the white, coastal buildings.

Throughout the awards ceremony, winners and runner-ups received compliments on a job well done. At closing, it was the attendees that complimented the organizers on a terrific event.

Complementary, Complimentary

Both words are used as adjectives. Like complement, complementary means “to make complete,” “to enhance,” or “to improve” (e.g., complementary plans). Complimentary means “to praise” (e.g., complementary remarks) or “to receive or supply free of charge.”

Only one thing is certain in the world of haute couture: fashion parties brimming with complimentary Champagne and endless banter on how colorful characters and complementary personalities rose to the occasion.

Differs from, Differ with

Use differ from in discussing characteristics. Use differ with to convey the idea of disagreement.

American English differs from British English.

The clerk differs with her manager on his decision to hire an additional salesperson.

Different from, Different than

These two word pairings are interchangeable. However, whereas different from is used to compare two nouns or phases, different than is commonly used when what follows is a clause.

Dolphins are different from porpoises.

My old neighborhood is different than it used to be.

Do to, Due to

Do to consists of the verb “do” followed by the preposition “to.” Due to is an adverbial phrase meaning “because of” or “owing to.” Due to is sometimes erroneously written as do to.

What can we do to save the mountain gorilla?

Roads are slippery due to heavy rain.

Each other, One another

Use each other when referring to two people. Use one another when referring to more than two people.

Two weight lifters helped spot each other.

Olympic athletes compete against one another.

Everyday, Every day

These words are not interchangeable. Everyday is an adjective that means either “ordinary” or “unremarkable” (everyday chores) or happening each day (an everyday occurrence). Every day is an adverb meaning “each day” or “every single day.”

Although we’re fond of talking about the everyday person, it’s difficult to know what this really means.

Health practitioners say we should eat fresh fruit every day.

Everyplace, Every place

These words are not interchangeable. Everyplace has the same meaning as “everywhere.” Every place means in “each space” or “each spot.”

We looked everyplace for that DVD.

Every place was taken by the time she arrived.

Everyone, Every one

These words are not interchangeable. Everyone means “everybody in a group” whereas every one means “each person.”

Everyone knows who did it!

Every one of the runners who crossed the finish line was exhausted but jubilant.

Everything, Every thing

Everything means “all things.” Every thing means “each thing.” Note that the word everything is much more common than its two-word counterpart.

Everything in this store is on sale.

Just because we don’t understand the role that each living organism plays, this doesn’t mean that to every thing there isn’t a purpose.

Every time, Everytime

Every time means “at any and all times.” It is always spelled as two separate words. Spelling it as one word is nonstandard and incorrect.

Every time we visit there’s always lots of food and drink.

Farther, Further

Use farther when referring to distance. Use further in all other situations, particularly when referring to extent or degree.

The town is one mile farther along the road.

We must pursue this idea further.

Fewer, Less

Fewer refers to things that can be counted, e.g., people, marbles, accidents. Less refers to things that cannot be counted, e.g., money, water, sand.

There are fewer students in class than before the midterm exam.

There is less water in the bucket due to evaporation.

If, Whether

Use if to express one possibility, especially conditional statements. Use whether to express two (or more) possibilities.

The company claims that you will be successful if you listen to their tapes on motivation.

Success depends on whether one has desire and determination. (The implied “whether or not” creates two possibilities.)

NOTE  In colloquial English, if and whether are now interchangeable. Either of the following sentences would be correct: “I’m not sure whether I’m going to the party.”/“I’m not sure if I’m going to the party.”

In colloquial English, if and whether are now interchangeable. Either of the following sentences would be correct: “I’m not sure whether I’m going to the party.”/“I’m not sure if I’m going to the party.”

Instead of, Rather than

These word pairs are considered interchangeable.

Lisa ordered Rocky Road ice cream instead of Mint Chocolate.

The customer wanted a refund rather than an exchange.

Infer, Imply

Infer means “to draw a conclusion”; readers or listeners infer. Imply means “to hint” or to suggest”; speakers or writers imply.

I infer from your letter that conditions have improved.

Do you mean to imply that conditions have improved?

Into, In to

These words are not interchangeable. Into means “something inside something else.” The phrase in to means “something is passing from one place to another.”

The last I saw she was walking into the cafeteria.

He finally turned his assignment in to the teacher.

Regarding the sentence above, unless the student were a magician, we could not write, “He finally turned his assignment into the teacher.”

Its, It’s

Its is a possessive pronoun. It’s is a contraction for “it is” or “it has.”

The world has lost its glory.

It’s time to start anew.

Lead, Led

The verb lead means “to guide, direct, command, or cause to follow.” Lead is the present tense of the verb while led forms the past tense (and past participle).

More than any other player, the captain is expected to lead his team during the playoffs. Last season, however, it was our goalie, not the captain, who actually led our team to victory.

It is a common mistake to write “lead,” when what is called for is “led.” This error likely arises given that the irregular verb “read” is spelled the same in the present tense and in the past tense. Ex. “I read the newspaper everyday, and yesterday, I read an amazing story about a ‘tree’ man whose arms and legs resembled bark.”

Lets, Let’s

Lets is a verb meaning “to allow or permit.” Let’s is a contraction for “let us.”

Technology lets us live more easily.

Let’s not forget those who fight for our liberties.

Lie, Lay

In the present tense, lie means “to rest” and lay means “to put” or “to place.” Lie is an intransitive verb (a verb that does not require a direct object to complete its meaning), while lay is a transitive verb (a verb that requires a direct object to complete its meaning).

Lie:

Present: Lie on the sofa.

Past: He lay down for an hour.

Perfect Participle: He has lain there for an hour.

Present Participle: It was nearly noon and he was still lying on the sofa.

Lay:

Present: Lay the magazine on the table.

Past: She laid the magazine there yesterday.

Perfect Participle: She has laid the magazine there many times.

Present Participle: Laying the magazine on the table, she stood up and left the room.

NOTE  There is no such word as “layed.” This word is the mistaken misspelling of “laid.” Ex. “A magazine cover that is professionally laid out,” not “a magazine cover that is professionally layed out.”

There is no such word as “layed.” This word is the mistaken misspelling of “laid.” Ex. “A magazine cover that is professionally laid out,” not “a magazine cover that is professionally layed out.”

Like, Such as

Such as is used for listing items in a series. Like should not be used for listing items in a series. However, like is okay to use when introducing a single item.

A beginning rugby player must master many different skills such as running and passing, blocking and tackling, drop kicking, and scrum control.

Dark fruits, like beets, have an especially good cleansing quality.

Loose, Lose, Loss

Loose is an adjective meaning “not firmly attached” or “not tightly drawn.” Lose is a verb meaning “to suffer a setback or deprivation.” Loss is a noun meaning “a failure to achieve.”

A loose screw will fall out if not tightened.

There is some truth to the idea that if you’re going to lose, you might as well lose big.

Loss of habitat is a greater threat to wildlife conservation than is poaching.

Maybe, May be

These words are not interchangeable. Maybe is an adverb meaning “perhaps.” May be is a verb phrase.

Maybe it’s time to try again.

It may be necessary to resort to extreme measures.

Might, May

Although might and may both express a degree of uncertainty, they have somewhat different meanings. Might expresses more uncertainty than does may. Also, only might is the correct choice when referring to past situations.

I might like to visit the Taj Mahal someday. (much uncertainty)

I may go sightseeing this weekend. (less uncertainty)

They might have left a message for us at the hotel. (past situation)

No one, Noone

No one means “no person.” It should be spelled as two separate words. The one-word spelling is nonstandard and incorrect.

No one can predict the future.

Number, Amount

Use number when speaking of things that can be counted. Use amount when speaking of things that cannot be counted.

The number of marbles in the bag is seven.

The amount of topsoil has eroded considerably.

Onto, On to

These words are not equivalent. Onto refers to “something placed on something else.” The phrase on to consists of the adverb “on” and the preposition “to.”

Ferry passengers could be seen holding onto the safety rail.

We passed the information on to our friends.

NOTE  We could not pass the information onto our friends unless the information was placed physically on top of them.

We could not pass the information onto our friends unless the information was placed physically on top of them.

Passed, Past

Passed functions as a verb. Past functions as a noun, adjective, or preposition.

Yesterday, Cindy found out that she passed her much-feared anatomy exam.

The proactive mind does not dwell on events of the past.

Principal, Principle

Although principal can refer to the head administrator of a school or even an original amount of money on loan, it is usually used as an adjective meaning “main,” “primary,” or “most important.” Principle is used in one of two senses: to refer to a general scientific law or to describe a person’s fundamental belief system.

Lack of clearly defined goals is the principal cause of failure.

To be a physicist one must clearly understand the principles of mathematics.

A person of principle lives by a moral code.

Sometime, Some time

These words are not interchangeable. Sometime refers to “an unspecified, often longer period of time.” Some time refers to “a specified, often shorter period of time.”

Let’s have lunch sometime.

We went fishing early in the morning, but it was some time before we landed our first trout.

Than, Then

Than is a conjunction used in making comparisons. Then is an adverb indicating time.

There is controversy over whether the Petronas Towers in Malaysia is taller than the Sears Tower in Chicago.

Finish your work first, then give me a call.

That, Which

The words which and that mean essentially the same thing. But in context they are used differently. It is common practice to use which with nonrestrictive (nonessential) phrases and clauses and to use that with restrictive (essential) phrases and clauses. Nonrestrictive phrases are typically enclosed with commas, whereas restrictive phrases are never enclosed with commas. This treatment means that which appears in phrases set off by commas whereas that does not appear in phrases set off by commas.

The insect that has the shortest lifespan is the Mayfly.

The Mayfly, which lives less than 24 hours, has the shortest lifespan of any insect.

That, Which, Who

In general, who is used to refer to people, which is used to refer to things, and that can refer to either people or things. When referring to people, the choice between that and who should be based on what feels more natural.

Choose a person that can take charge.

The person who is most likely to succeed is often not an obvious choice.

NOTE  On occasion, who is used to refer to non-persons while which may refer to people.

On occasion, who is used to refer to non-persons while which may refer to people.

I have a dog who is animated and has a great personality.

Which child won the award? (The pronoun which is used to refer to a person.)

There, Their, They’re

There is an adverb; their is a possessive pronoun. They’re is a contraction for “they are.”

There is a rugby game tonight.

Their new TV has incredibly clear definition.

They’re a strange but happy couple.

Toward, Towards

These words are interchangeable: toward is American English while towards is British English. A given document should show consistent treatment.

Used to, Use to

These words are not interchangeable. Used to is the correct form for habitual action. However, when “did” precedes “used to” the correct form is use to.

I used to go to the movies all the time.

I didn’t use to daydream.

Who, Whom

“Who” is the subjective form of the pronoun and “whom” is the objective form. The following is a good rule in deciding between who and whom: If “he, she, or they” can be substituted for a pronoun in context, the correct form is who. If “him, her, or them” can be substituted for a pronoun in context, the correct form is whom. Another very useful rule is that pronouns take their objective forms when they are the direct objects of prepositions.

Let’s reward the person who can find the best solution.

Test: “He” or “she” can find the best solution, so the subjective form of the pronoun — "who" — is correct.

The report was compiled by whom?

Test: This report was drafted by “him” or “her,” so the objective form of the pronoun — "whom" — is correct. Another way of confirming this is to note that “whom” functions as the direct object of the preposition “by,” so the objective form of the pronoun is correct.

One particularly tricky situation occurs in the following: “She asked to speak to whoever was on duty.” At first glance, it looks as though “whomever” should be correct in so far as “who” appears to be the object of the preposition “to.” However, the whole clause “whoever was on duty” is functioning as the direct object of the preposition “to.” The key is to analyze the function of “whoever” within the applicable clause itself; in this case, “whoever” is functioning as the subject of the verb “was,” thereby taking the subjective form. We can test this by saying “he or she was on duty.”

Let’s analyze two more situations, each introduced by a sentence that contains correct usage.

1) “I will interview whomever I can find for the job.” The important thing is to analyze the role of “whomever” within the clause “whomever I can find” and test it as “I can find him or her.” This confirms that the objective form of the pronoun is correct. In this instance, the whole clause “whomever I can find” is modifying the word form “will interview.”

2) “I will give the position to whoever I think is right for the job.” Again, the critical thing is to analyze the role of “whoever” within the clause “whoever I think is right for the job.” Since we can say “I think he or she is right for the job,” this confirms that the subjective form of the pronoun is correct. In this instance, the whole clause “whoever I think is right for the job” is modifying the preposition “to.” Therefore, this example mirrors the previous example, “She asked to speak to whoever was on duty.”

Whose, Who’s

Whose is a possessive pronoun. Who’s is a contraction for “who is.”

Whose set of keys did I find?

He is the player who’s most likely to make the NBA.

Your, You’re

Your is a possessive pronoun. You’re is a contraction for “you are.”

This is your book.

You’re becoming the person you want to be.

AVOIDING TWO COMMON ADMISSIONS BLUNDERS

Tip #94: Avoid two common bloopers: Forgetting to switch school names in your applications and implying that practice is the only way to “learn” about business.

Tip #94: Avoid two common bloopers: Forgetting to switch school names in your applications and implying that practice is the only way to “learn” about business.

Forgetting to Switch School Names

Every year admissions officers receive application essays which read wonderfully except that they contain the names of the wrong business school. For example, a person completing a London Business School application states, “This is why I want to apply to INSEAD.” Obviously, this is not going to do wonders for your application chances. This may strike you as an oversight that you would never commit yourself. However, when pressured by deadlines, and when cutting and pasting parts of one application to fit another, it becomes a lingering possibility.

Saying You Cannot Learn Business from Books

If you write in your application essays that businesspeople don’t learn from books, or that entrepreneurship cannot be taught, you should stop and think about what you are saying. The admissions reviewers will likely want to respond by asking why you want to go to business school. Of course, any mature, seasoned businessperson would surely recognize that effective and efficient business practices best combine theory and practice. And this is hardly different from any other practical endeavor. No sane person would try to build a large home without a blueprint. What’s a blueprint? It’s the theory. And it’s an integral part of the solution. Period.

If you say you cannot learn from books (notwithstanding the fact that books are not the only tool one can learn from in business school), you are belittling the role of business schools, business school administrators, and business school professors. Any business professor would acknowledge that theory is important in making optimum decisions and avoiding fundamental mistakes. Saying that books or theories don’t “count” is a blooper from the admissions side of the equation.

TIPS FOR WRITING SMART

Tip #95: Avoid MBA speak.

Tip #95: Avoid MBA speak.

MBA speak is easier to illustrate than to describe. It refers to a style of writing that has a business focus, but is full of jargon and generalities. Our goal is to keep MBA speak out of our writing. When it does appear, we must edit out the jargon and turn generalities into specifics.

I quickly learned IT best practices and took charge developing the new operating model, building the governance framework and modeling resource capacity. Our team proactively involved the partner and the client in our activities, and I contributed by ensuring the CIO and his team addressed critical action items. We built on each others ideas and leveraged individual strengths. Through collaborative teamwork, we were able to complete the project and ultimately change the client’s perception.

Encountering MBA speak causes us to reread the same sentences over because the words don’t stick. Our mind is hearing the words, but we are unable to grab hold of them. Conquering MBA speak requires attacking the jargon and vague terms. In the previous passage, we ask, What does “governance framework” or “modeling resource capacity” or “critical action items” really mean? If they are precise technical terms, we could place short definitions in brackets right next to each of them as they are introduced. Vague terms include "best practices," “proactively involved,” “leveraging individual strengths,” “collaborative teamwork,” and “client’s perception.” We want to replace these words with words that better describe the situation. For instance, what are the exact strengths of each team member, how is teamwork collaborative, and what were those aspects of the client’s perception that were changed.

Tip #96: Favor politically correct writing.

Tip #96: Favor politically correct writing.

The masculine generic refers to the sole use of the pronoun “he” or “him” when referring to situations involving both genders. Avoid using “he” when referring to both “he or she”; likewise avoid using “him” when referring to both “him or her.” Avoiding the masculine generic and maintaining gender-neutral language signals to the reader that you are sensitive in acknowledging both sexes. The simple fact is that greater than 50 percent of admissions personnel are female. Thus, it is not only politically correct, but also politically astute to avoid using the masculine generic.

Consider the way the following sentences read from a female perspective:

Original: Today’s chief executive must be extremely well rounded. He must not only be corporate and civic minded, but also be internationally focused and entrepreneurially spirited.

There are essentially two ways to “fix” this:

Either write “he” or “she” (or “him” or “her”):

Today’s chief executive must be extremely well rounded. He or she must not only be corporate and civic minded, but also be internationally focused and entrepreneurially spirited.

Or put the sentence in the plural using “they” or “them”:

Today’s chief executives must be extremely well rounded. They must not only be corporate and civic minded, but also be internationally focused and entrepreneurially spirited.

Tip #97: Think in terms of a top-down, expository writing style. Be able to summarize any essay in just one sentence.

Tip #97: Think in terms of a top-down, expository writing style. Be able to summarize any essay in just one sentence.

MBA essay writing is expository writing. The primary purpose of expository writing is to inform or persuade, not to entertain. Writing that exists to inform or explain should follow a top-down writing style, also known as the “inverted pyramid approach.” This means that we conclude at or near the top and then proceed to supply details. If the reverse occurs, inefficiency will result, because the reader will not be able to figure out the main point of our writing until the end, and details, therefore, will be much harder to remember. Perhaps the best example of the top-down approach in action is the newspaper. Newspaper writers know that if a story is too long and needs to be cut, the editor will start at the bottom and work up. Simply put, this is where the least critical information is. Contrast this with the world of entertainment (movies and TV shows), or the creative world of fiction, where we enjoy and expect surprise endings. We would never want to go to a movie and be told at the very beginning what the whole movie was about. This is not the case in the world of expository writing, of which MBA essay writing is a subset. Don’t play “I’ve got a secret” and leave the reader guessing.

Favor the top-down approach to writing:

Avoid the bottom-up approach to writing:

Tip #98: Focus your writing. Try not to discuss too many things at one time.

Tip #98: Focus your writing. Try not to discuss too many things at one time.

Try not to discuss too many ideas at one time. Remember that it’s better to do “a lot with a little” than “a little with a lot.” As a fairly reliable generalization, it is true that most MBA applicants are prone to make a similar mistake with essay content. They try to cover too many topics in a given essay, sacrificing depth of writing. Given the fact that essays have length limits, discussing too many things will inevitably lead to superficiality.

Consider the following analogy that centers on storytelling. You have just spent a year traveling around the world. You arrive back to tell a bunch of your friends all about your epic journey (over beers!). You know it’s impossible to explain everything about the vast terrain you’ve traveled in a three hour chat-fest. So you naturally focus in on one of the most memorable, quintessential, intriguing, unexpected parts of the journey — the day you went to the market in Morocco. You build your first travel story about your trip to Morocco and everything else flows from that nexus.

The technique of focusing conversation is the same in speaking, or storytelling, as it is in writing. A laundry list of places traveled, coupled with a chronology of the means of transportation used to get from place to place is hardly interesting. It is the detail and the cohesiveness of the message that moves us as listeners or readers. Just as a great storyteller knows how to build a story around a key person, place, thing, or idea, so too does the good writer know how to narrow the focus to engender interest. This is where the seasoned writer is separated from the amateur. The seasoned writer knows of the impossible task at hand that lies in trying to cover “everything” in one page, so he or she focuses instead on one aspect of the topic at hand, and in taking a stand, a memorable writing piece is created.

Tip #99: Cherish the “for example” technique.

Tip #99: Cherish the “for example” technique.

The following sentences were taken from application essays written by prospective business school students. Each statement made by the candidate is matched by a response that likely exists in the mind of the reviewer immediately after reading the sentence. One of the best tips to use to avoid vagueness in your writing and help ensure that you lend adequate support for the points you are making involves placing “for example” immediately after what you write, and proceeding to add support. As a practical matter, it is up to the writer to decide whether to leave “for example” in your essay or edit it out, particularly if you are looking for more seamless connections between ideas and support points.

Candidate: Growing up in both the East and West, I have experienced both Asian and Western points of view.

Reviewer: Do you mind telling me what these Asian and Western points of view are?

Candidate: I am an energetic, loyal, creative, diligent, honest, strict, humorous, responsible, flexible, and ambitious person.

Reviewer: Do you care to develop your discussion by choosing two or three of these traits and supporting each with concrete examples?

Candidate: Although ABC Company did not flourish, I still consider my effort a success because I was able to identify strengths and weaknesses in my overall business skills.

Reviewer: What were the strengths and weaknesses you were able to identify?

Candidate: Not only did I develop important operational skills in running a business, but I experienced and witnessed the challenges that entrepreneurs face on a daily basis.

Reviewer: What were these challenges?

Candidate: I believe teamwork, along with leadership, is the key to business success because no one person can do everything or possesses the know-how and temperament to solve every problem.

Reviewer: Wonderful, but I sure hope you’re going to tell me more about how know-how and temperament are key factors in the successful execution of teamwork and/or leadership.

Candidate: Sleeping in cheap hostels and on Eurorail trains, I got a much better picture of life in Europe than tourists do from the windows of a moving bus.

Reviewer: Prove it!

The following pairings address vagueness in writing. The “original” statement is vague while the “better” example incorporates detailed support.

Original: Sometimes I wish I could entertain broader points of view, especially those that directly attack my value system. It is important to hold to one’s convictions and not be unduly persuaded by others.

Better: Sometimes I wish I could entertain broader points of view especially those that directly attack my value system. For example, during one of our community college fundraising brainstorming sessions, a member of the committee suggested organizing a rave party and donating profits to the school. Although I could see that an event like this would generate a sizable profit, I vetoed the idea based on two considerations: the first was its association with a rave party, which has strong drug-related connotations, and the second, the inappropriateness of not informing the donors of our purpose.

Original: My college education in Florida provided me with an incredible chance to develop myself. I pursued a rich choice of academic, athletic, professional, and social activities. At different times during my undergraduate education, I was a member of the Varsity Debate Team, Varsity Tennis Team, and a member of both a well-known professional business fraternity and a social fraternity.

Better: My college education in Florida provided me with an incredible chance to develop myself. I pursued a rich choice of academic, athletic, professional, and social activities. At different times during my undergraduate education, I was a member of the Varsity Debate Team, Varsity Tennis Team, and a member of both a well-known professional business fraternity and a social fraternity. Using just a few words to summarize what each experience taught me: from debate, I learned to be organized and think ahead; from tennis, I learned to be persistent and not give up; and from my business and social fraternities, I learned to work in groups, work with rules, and value personality.

Original: I grew up in a Maine farm family that was ethnically Scottish, but really your everyday New England household. I am thankful now for a stable, happy childhood. My parents gave me the best education and upbringing they could. They taught me to be caring and respectful of people and the environment. They taught me honesty, humility, and the silliness of pretense.