NATACHA RAMBOVANATACHA RAMBOVA

“Even her worst enemy has admitted the genius of Natacha,” Herb Howe wrote of Natacha Rambova in 1930, “that unquenchable flame of ambition that sweeps out from her ruthlessly.”

The woman known the world over by the striking Russian name was born Winifred Kimball Shaughnessy in Salt Lake City on January 19, 1897. Her father, Michael Shaughnessy, a hero of the Civil War, and her mother, Winifred Kimball, an interior decorator, separated when she was young because of Michael’s heavy drinking and gambling. The elder Winifred remarried twice, first to Edgar De Wolfe, brother of interior decorator Elsie De Wolfe, and then to wealthy perfumer Richard Hudnut.

Rambova studied ballet while attending boarding school in Great Britain. She began an affair with the Russian ballet dancer Theodore Kosloff when she was only seventeen. She changed her name to Natacha Rambova to dance professionally. When her mother discovered the affair, she pursued statutory rape charges against Kosloff. Eventually, the charges were dropped and Kosloff and Rambova settled in Los Angeles, where he began acting and designing films for Cecil B. DeMille.

Rambova helped Kosloff with the designs, and he passed Rambova’s work off to DeMille and others as his own. For Billions (1920), Kosloff submitted Rambova’s designs to Alla Nazimova, which she used in the film. For Nazimova’s next proposed film, Aphrodite (unmade), Kosloff made the mistake of sending Rambova to meet the actress instead of going himself. As Rambova made changes to the sketches in Nazimova’s presence, the actress realized that they were Rambova’s designs, not Kosloff’s. Nazimova hired Rambova to design Aphrodite, sending Kosloff into a rage. When Rambova announced that she was leaving him, Kosloff shot her in the leg. Rambova never reported the incident to police to avoid any further contact with Kosloff.

In 1921, Rambova met unknown actor Rudolph Valentino while he was making Uncharted Seas (1921). Nazimova introduced the two because she intended to cast Valentino as Armand in Camille (1921). Valentino had just finished The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), which would establish him as a star, but it had not yet been released. Given the legend that their romance would spawn, Rambova and Valentino’s initial meeting was disappointingly uneventful, at least for Rambova.

“I remember the first day he came on to the set, I disliked him,” Rambova said. “At that time I was very serious, running about in my low-heeled shoes and taking squints at my sets and costumes. Rudie was forever telling jokes and forgetting the point of them, and I thought him plain dumb.” She did not realize that she had piqued Valentino’s interest. “Then it came over me suddenly one day that he was trying to please, to ingratiate himself with his absurd jokes,” Rambova recalled. “‘Oh, the poor child,’ I thought. ‘He just wants to be liked—he’s lonely.’ And, well, you know what sentiment leads to . . .”

Rambova had a unique personal style. She wore turbans and bangle bracelets. She favored designers like Paul Poiret. She loved fabrics that reflected light, and designs that showed off the human form. Her sets and costume designs for Camille embodied an art deco sensibility, which was the rage in Europe at the time. But Camille may have been too much of an art film. When audiences rejected it at the box office, Metro Pictures canceled Nazimova’s contract. Nazimova Productions released its next feature, A Doll’s House (1922), through United Artists. It also featured Rambova’s sets and costumes.

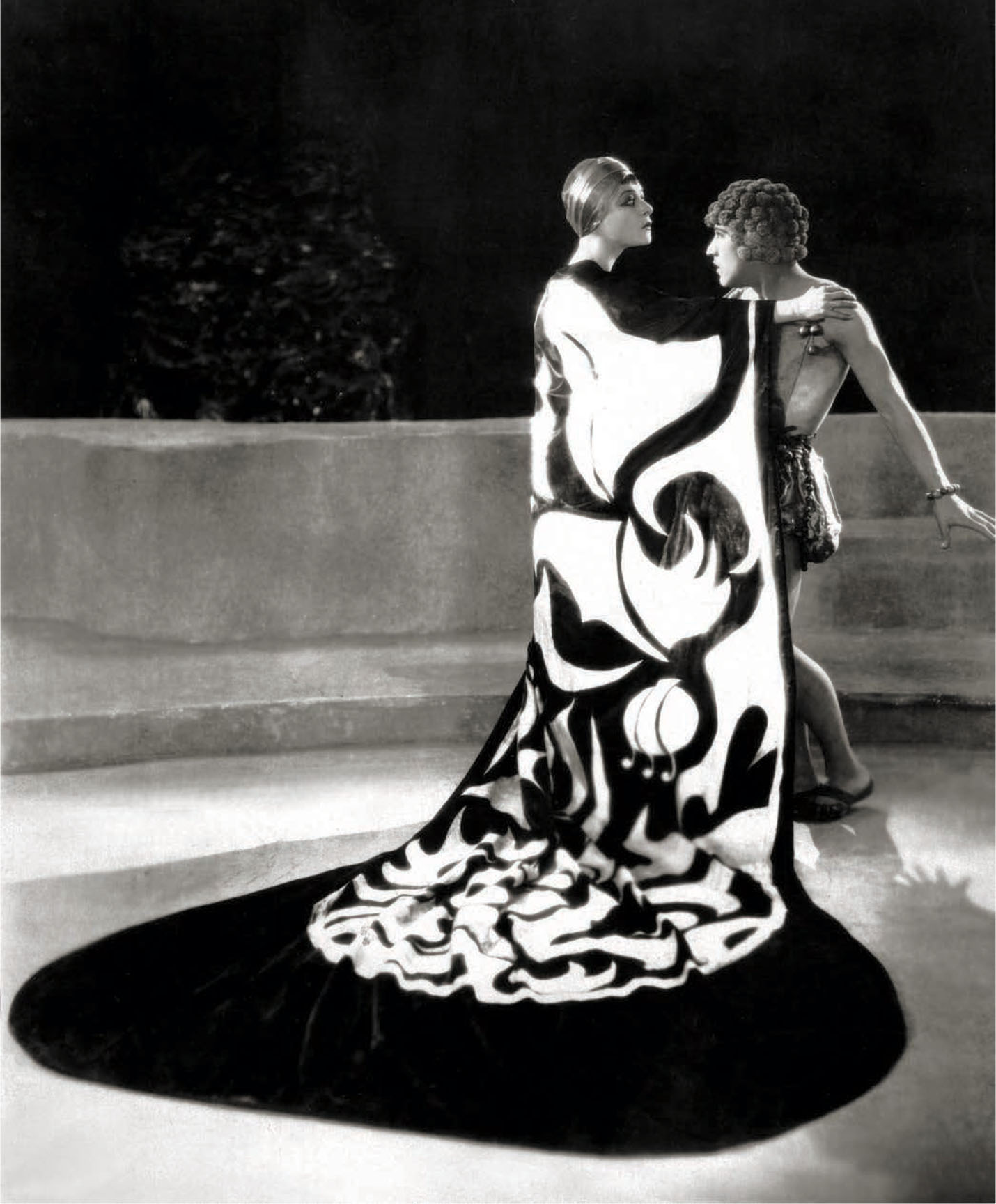

Rambova and Nazimova’s final collaboration, Salomé (1922), was perhaps Hollywood’s first art film, as it was clearly experimental, even by today’s standards. Rambova’s minimalist sets looked like peculiar stage scenery. Her highly stylized costumes matched Nazimova’s bizarre hairdos, which included glowing light spheres. Shirtless male actors sported nipple paint and giant bead necklaces. “The settings and composition of the scenes, devised by Natacha Rambova, correspond in a measure to the drawings by Aubrey Beardsley (in Oscar Wilde’s published play); and this visual beauty, as background to the fantastic flare and vivid drama of the story, gives the Nazimova Salomé an added artistry,” wrote the Exhibitors Herald. Public response was not so enthusiastic. Audiences stayed away en masse. The disaster ended Nazimova’s career as a producer.

Natacha Rambova and husband Rudolph Valentino.

Valentino was charged with bigamy and jailed shortly after Rambova married him in Mexico on May 22, 1922. Although Valentino’s first wife, actress Jean Acker, had obtained a divorce decree prior to the Rambova nuptials, Valentino had failed to wait the mandatory waiting period under California law before remarrying. Before the year was over, contract disputes arose between Valentino and Famous Players-Lasky, resulting in lawsuits in court, and a struggle for public sympathy in the press. When the studio successfully obtained an injunction preventing Valentino from acting for other studios, his new agent, George Ullman, suggested he and Rambova go on a dance tour, sponsored by Mineralava products, to keep the couple financially solvent. The tour was a great success. It ended with the couple marrying again, this time legally, on March 14, 1923.

Rambova became Valentino’s manager, and his career seemed to suffer instantly. In Monsieur Beaucaire (1924), Valentino played a seventeeth-century duke. Although Rambova, George Barbier, and René Hubert designed beautiful period costumes for Valentino, his fans did not expect or accept the star in powdered wigs and frilly ruff collars. The film flopped. Valentino’s next film, A Sainted Devil (1924), showed a return of the Latin lover image, but script revisions caused the film to suffer. Rambova was increasingly blamed in the press for Valentino’s failures.

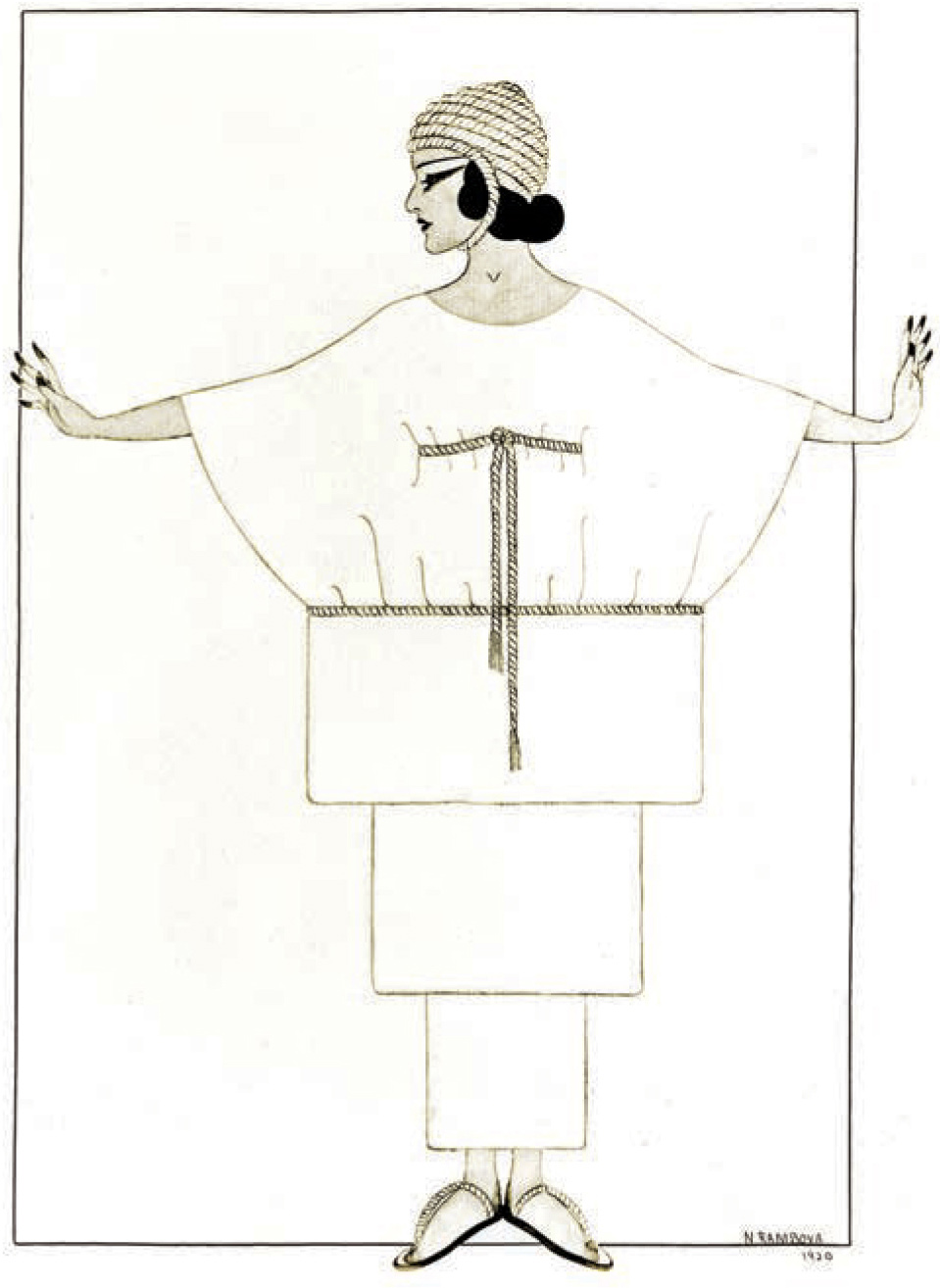

Costume sketch by Natacha Rambova, possibly for Alla Nazimova in Aphrodite (never made).

Misstep after misstep plagued their next production, The Hooded Falcon (unmade), to be produced by Ritz-Carlton. Valentino tabled the project and made Cobra (1925) instead. Ritz-Carlton hired Adrian to costume the players, thereby minimizing Rambova’s involvement. After talks failed to resolve The Hooded Falcon disputes, Ritz-Carlton canceled the project and Valentino’s contract.

United Artists offered Valentino a contract with the stipulation that Rambova had no negotiating power, nor could she even visit the sets of his films. To placate the outraged Rambova, Ullman co-produced What Price Beauty? (1925), starring and written by Rambova. The film did not do well at the box office.

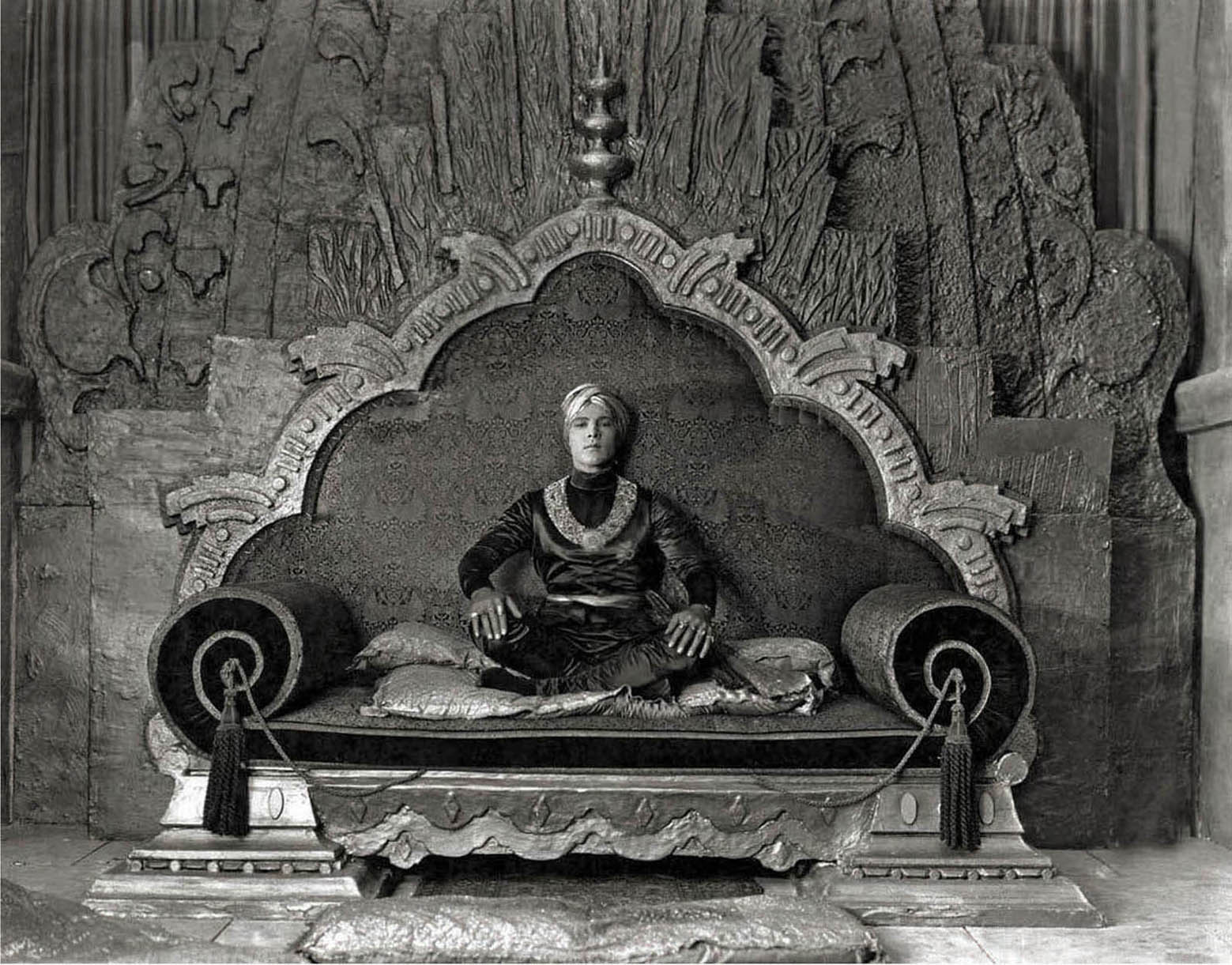

Rudolph Valentino in The Young Rajah (1922).

Under the strain of failed business collaborations, and because Rambova did not want to have children, Valentino and Rambova separated in 1925 and were divorced in 1926. By the time of the divorce, Valentino’s next two films The Cobra (1925) and The Son of the Sheik (1926) put his career on track again.

As the Valentino divorce was being finalized, Rambova was given an opportunity to act in Do Clothes Make the Woman? The film, about an oil executive who tries to break up the marriage between a young inventor and his wife, was re-titled When Love Grows Cold, to Rambova’s dismay. She was further insulted when the producer billed her as Mrs. Rudolph Valentino. Hurt and humiliated, she never worked on another film.

In August 1926, Valentino was hospitalized in New York City with appendicitis and gastric ulcers. Hearing of his grave condition, Rambova telegraphed Valentino from France. The couple exchanged telegrams, and Rambova viewed this as a reconciliation. After a brief rally, Valentino relapsed with pleurisy and died on August 23, 1926. Rambova was inconsolable and did not attend the funerals in New York or Los Angeles.

Rambova remained a pariah in Hollywood following Valentino’s death. In 1927, she found some success opening a couture shop on Fifth Avenue in New York City. In 1934, she married Spanish aristocrat Alvaro de Urzaiz and moved to the island of Mallorca with him. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, Urzaiz stayed to fight, and Rambova moved to France. Rambova suffered a heart attack shortly afterward, and the couple divorced in 1939. When World War II started, Rambova returned to New York and taught classes in Egyptology and mysticism. She amassed a well-regarded collection of Far Eastern and Egyptian art. When she became ill in the early 1960s with scleroderma, brought on by years of anorexia nervosa, Rambova moved to Pasadena to be looked after by a cousin. She died there of a heart attack on June 5, 1966.

Alla Nazimova in Salomé (1922).

Though Rambova has been revered for her costume and set designs, and later was respected as a scholar, her legacy remains the villainess who destroyed Valentino’s career. “I’m glad Rudie died when he did, while the world still adored him,” Rambova said in 1930. “The death of his popularity would have been a thousand deaths to him. Of course he might have gone on, but I’m afraid today we have a realism in pictures and on the stage. Rudie belonged to the age of romance. He brought it with him, it went with him. I think it was a climax he would have wished.”