MITCHELL LEISEN AND NATALIE VISARTMITCHELL LEISEN AND NATALIE VISART

She was a high-school gal pal of Cecil B. DeMille’s daughter Katharine. He was the son of a Midwestern beer baron and had established himself as a Hollywood costume designer and art director.

The two met at DeMille’s house during the time Leisen was collaborating with the director on The Volga Boatman (1926), and Visart was hanging out with the director’s daughter after school.

Visart had been born Natalie Visart Schenkelberger in Chicago on April 14, 1910. Her father, Peter C. Schenkelberger, a tall, bald man with a withered left leg, was a surgeon; and her mother, Marie Gertrude Debury, was a Canadian immigrant. Visart expected to follow her father in a medical career as a nurse. But in September of 1920, her respiratory health issues prompted her father to send Visart to live in California. She met Katharine DeMille at the Hollywood School for Girls. The DeMille family befriended Visart, inviting her to spend weekends and school vacations with them.

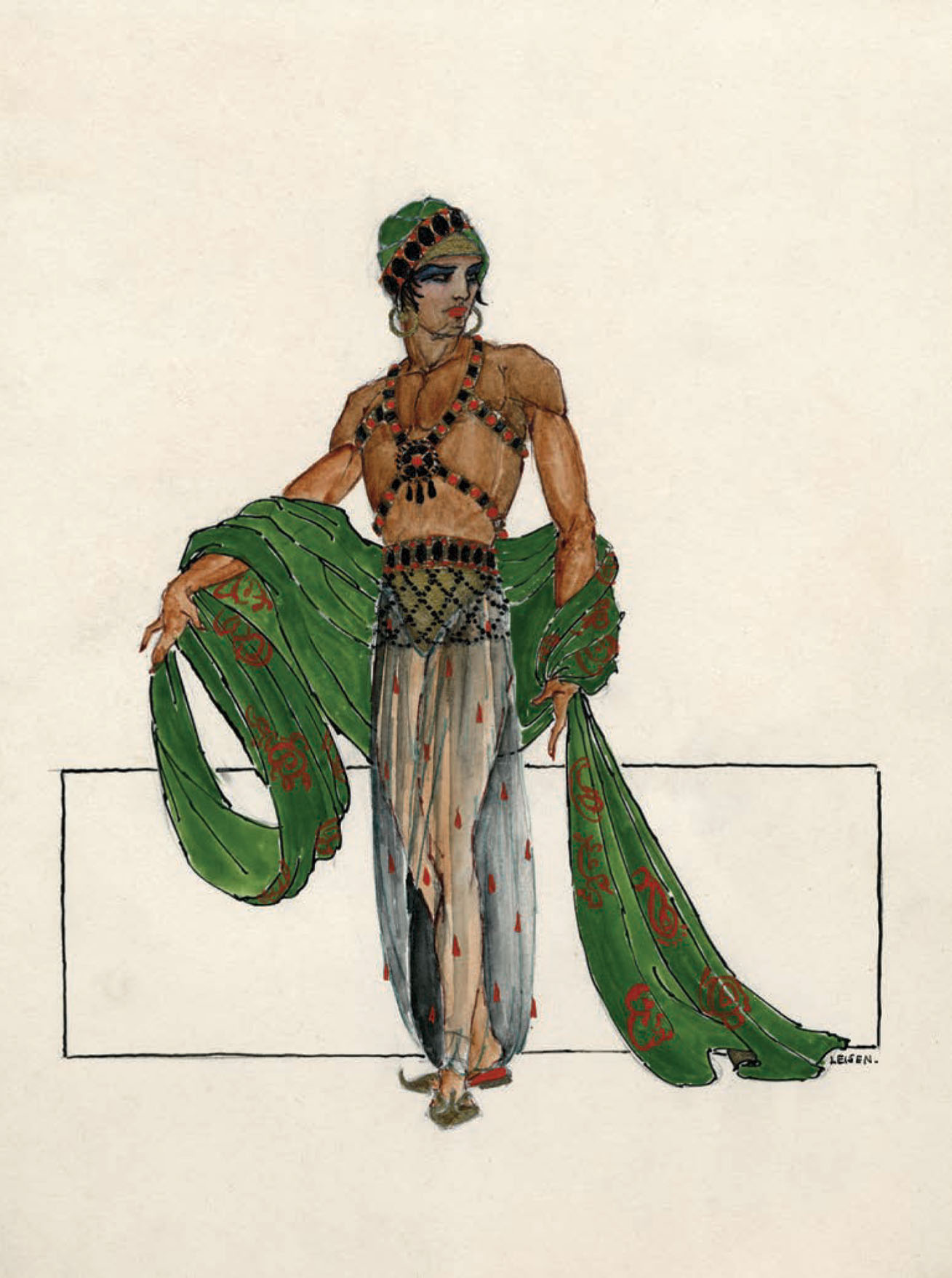

Just before Visart’s move to California, an encounter with DeMille at a dinner party had brought Leisen his first job as a costume designer, making clothes for superstar Gloria Swanson in DeMille’s Male and Female (1919). Leisen was aggressively unqualified for the task. “DeMille approved my sketch and then told me I had to do fifty more and supervise the making of them,” Leisen recalled years later. “I had never made a dress in my life and I didn’t know the first thing to do. Clare West was the head of wardrobe at Lasky studio, and she wasn’t about to have me making anything in her workroom. She stuck me in a little room about four by six with six seamstresses, and I sweated the whole thing out myself.”

True to his reputation for extravagance, DeMille requested something startling for Swanson in the sequence, “When I Was a King of Babylon and You Were a Christian Slave.” Leisen designed a gown dyed in batik—an ancient technique from Java using wax and pigments—and embroidered with pearls. The ensemble included a peacock-shaped, feathered headdress also embroidered in pearls. To give the diminutive Swanson more stature, Leisen used clogs shaped like Babylonian bulls with wings coming up the sides of Swanson’s feet to hold them on. “You had to learn to think the way he thought, in capital letters,” Leisen said of DeMille. “Everything was in neon lights six feet tall: Lust, Revenge, Sex.”

Creating over-the-top designs to satisfy DeMille’s grandiose tastes seemed like an unlikely vocation for Leisen given his beginnings as an awkward, shy child. He was born Jacob Mitchell Leisen on October 6, 1898, in Menominee, Michigan, where his father was a partner in the Leisen & Henes Brewing Company. His parents divorced while Leisen was a toddler; he was raised by his mother and stepfather in St. Louis. At age five, Leisen underwent an operation to correct a club foot that left him with a slight limp for the rest of his life. Introverted as a child, Leisen spent hours alone building models of theaters and arranging flowers. Alarmed by his atypical boyhood interests, Leisen’s parents sent him to military school. It never had the desired effect, as Leisen went on to study architecture and commercial design at Washington University in St. Louis.

As an interior designer for the Chicago architectural firm of Marshall and Fox, Leisen realized some of his boyhood dreams of theatrical design by planning the interior decor of the Powers Theater and the ballroom of the Edgewater Beach Hotel. When business at the firm slowed, Leisen took a sabbatical in Hollywood, and taking the advice of his cousin, stage and film actress Kathleen Kirkham, gave films a try.

Leisen stayed in Los Angeles with family friends Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, who were pioneers of modern dance. They introduced Leisen to Jeanie Macpherson, Cecil B. DeMille’s valued screenwriter. Impressed with Leisen, Macpherson introduced him to her boss.

At the end of his first year, Leisen asked DeMille to put his architectural skills to use by letting him design sets. DeMille assigned Leisen to do sets for his brother, William DeMille, and set dressing for himself. After several blowups with Paul Iribe, DeMille’s art director, Leisen was fired.

Gloria Swanson in Male and Female (1919).

Leisen bounced back immediately, getting a dream job with Douglas Fairbanks. He moved into Pickfair, the home of Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, as their guest while he designed Fairbanks’s wardrobe for Robin Hood (1922). Leisen strove for authenticity in the film, giving each soldier his own crest with matching tabard, shield, and helmet. He also styled an enormous piece of burlap to look like tapestry, which Fairbanks used to slide down to the ground from atop the castle to escape the villain.

The following year, Leisen designed Rosita (1923) for Mary Pickford and The Courtship of Myles Standish (1923), neither of which was particularly well received. Next came The Thief of Bagdad (1924), one of the most expensive films of the decade and the first by art director William Cameron Menzies. In a truly impressive feat, Douglas Fairbanks and Julanne Johnstone flew over a crowd of three thousand extras on a flying carpet, suspended by just four piano wires.

In 1927, Leisen married opera singer Stella Seager, known professionally as Sandra Gahle, in a ceremony at DeMille’s ranch. Although they would remain married for fifteen years, their marriage was anything but traditional. The two lived apart frequently. Gahle even lived in France for a few years studying voice. Leisen had numerous dalliances, which Gahle knew about, and did not seem to mind. Some lovers were men. Others were women. And one was Visart.

Visart was undoubtedly flattered to receive the attention of a successful older man, at least initially. Ultimately their connection was as much cerebral as physical, according to Visart’s daughter, Laurel Taylor. The two “got” each other, she said. And Leisen proved helpful to Visart’s career. As he began working as a director in 1933, he positioned Visart to take his place as DeMille’s costume designer. By 1936, she was assigned to costume The Plainsman.

A costume sketch by Mitchell Leisen for Male and Female (1919).

Natalie Visart and Ray Milland out on the town.

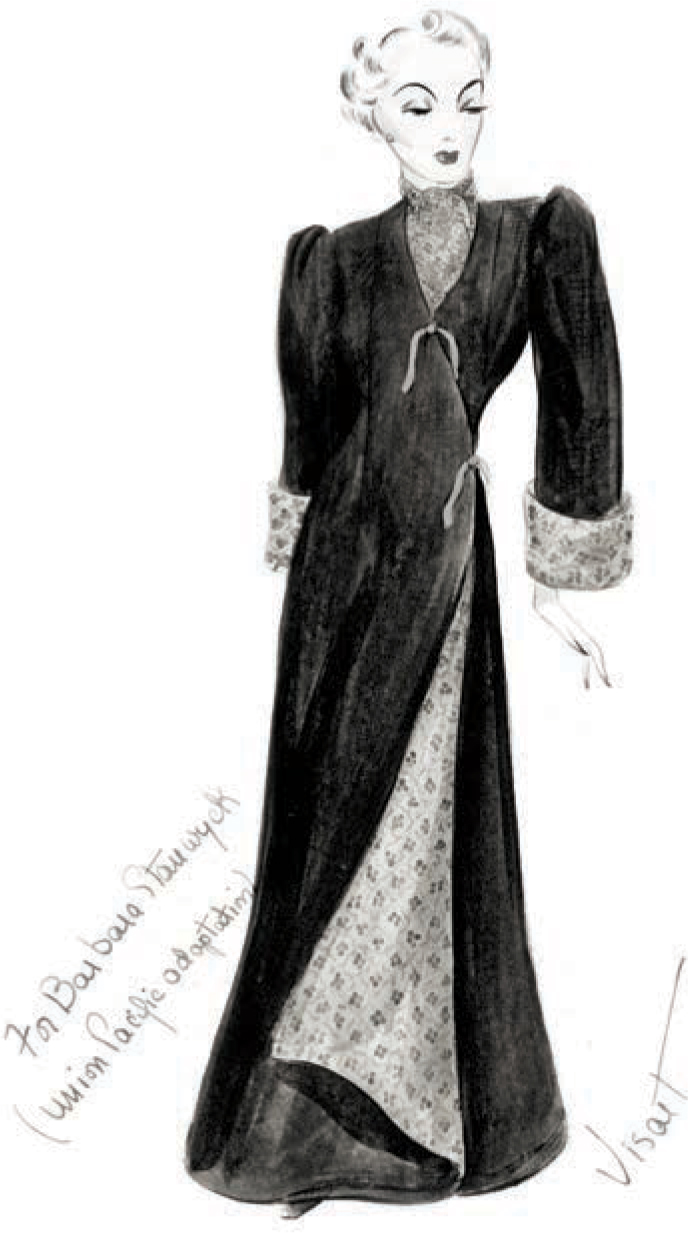

An adaptation of a design for Barbara Stanwyck in Union Pacific (1939) by Natalie Visart.

Despite his marriage to Gahle, Leisen openly lived with Visart during the 1930s. He also carried on with his flying instructor, Edward Anderson. Leisen eventually made Anderson an assistant director on The Big Broadcast of 1938. Because the two men had an outwardly plausible non-sexual pretext for their rendezvous, appearance-conscious Visart tolerated the affair, which did not last. During production of Big Broadcast, Anderson’s affections turned from Leisen to leading lady Shirley Ross. When the loss of Anderson to Ross seemed inevitable, Leisen began pursuing dancer and choreographer Billy Daniel.

The upheaval in Leisen’s personal life took a toll on him. On the last night of shooting Big Broadcast, Leisen suffered a serious heart attack. His subsequent recovery changed him. He became cranky. And he no longer showed any discretion regarding his libido. While Visart could adjust to Leisen’s cantankerous personality shift, she could not abide him flaunting his relationship with Daniel. She left Hollywood to work for milliner Lily Dache in Paris, even though her career as DeMille’s costume designer had just started to take off. Visart was not gone from Hollywood long though. As the Nazis menaced Europe, she returned to Los Angeles, where DeMille welcomed her back by hiring her to design the wardrobe for North West Mounted Police (1940). The war in Europe also prompted Gahle to return to the United States, settling in San Francisco, where she performed with the local opera.

Despite her misgivings, Visart resumed her affair with Leisen. He induced Barbara Stanwyck to hire her for Meet John Doe (1941), a collaboration that resulted in some of Visart’s best work. More than fifty years later, Visart’s white outfit which Stanwyck wears as her character reveals that she is in love with Gary Cooper still drew accolades for its story-telling power. Stanwyck’s character “sold out so hard, so fast, so elegantly, and it’s all expressed in that costume,” director Michael Tolan said in 1995. “Everyone wants costume to express character transformation. That’s almost too extreme a transformation, but it works because she looks so great.” After Meet John Doe, DeMille induced Paramount to offer Visart a contract, but she declined, telling DeMille that she was afraid that during downtime “Edith (Head) would have me picking up pins off the workroom floor.” She decided to sign with producer Hunt Stromberg instead.

In late 1942, Visart found herself in the same difficult position Loretta Young had been in 1935, when she conceived Clark Gable’s child on the set of The Call of the Wild (1935). Visart, who had worked on The Crusades with Young, now found herself carrying Leisen’s child. Because Young had worn loose-flowing costumes in the medieval drama, made right after Call of the Wild, no one realized she was pregnant. “Natalie was one of the people in on the fact then that Loretta had adopted her own daughter,” film historian David Chierichetti said. “So when Natalie got pregnant, it occurred to her and Mitchell that they would do the same thing.” Visart would have probably preferred to marry Leisen, but she could not. Although Gahle moved to Idaho in 1942, specifically to establish residency to sue Leisen for divorce, he would not be single again until after the child’s birth. Even then, because Visart was a devout Catholic, she would not be able to marry Leisen as a divorced man until the Vatican annulled his marriage to Gahle. These issues became moot when Visart miscarried. In a cruel twist of irony, soon after the miscarriage Paramount sent Leisen the script of To Each His Own (1946), which recounts the story of a woman who adopts her own child. He turned it down initially, saying that it was too close to Madame X (1937), but in reality, it was too close to his own life. Leisen did eventually direct To Each His Own, for which Olivia de Havilland won an Oscar for Best Actress.

On March 30, 1946, Visart married writer Dwight Bixby Taylor, soon after meeting him at a party. He was one of the first “Talk of the Town” editors for The New Yorker and later a noted novelist, playwright, and screenwriter. Taylor was himself the child of famous parents, actress Laurette Taylor and producer Charles Taylor.

Costume sketch for Douglas Fairbanks in The Thief of Bagdad (1924) by Mitchell Leisen.

During his career, Leisen directed some of Paramount’s most sparkling and witty comedies, including Easy Living (1937) and Midnight (1939). Visart and Leisen stayed in touch through the decades to come.

Leisen died of heart disease on October 28, 1972 in Woodland Hills, California. Natalie and Dwight died three months apart in 1986, both at the Motion Picture Retirement Home. Natalie died September 11 and Dwight on December 31.