Photographer Robert T. Landry returned home at 3:30 a.m. on June 29, 1947, to the guesthouse he rented from former Universal Studios costume designer Vera West. Vera and her husband, Jacques, lived in the main house at 5119 Bluebell Avenue—a beautiful Mellenthin residence that the couple had built just a decade before.

Landry, a thirty-three-year-old retired Life magazine photojournalist who lensed the famous World War II pin-up image of Rita Hayworth, was hoping to break into the movie business. As he carefully entered the property so as not to disturb the Wests in the wee hours of Sunday morning, he was surprised to find the Wests’ beloved Scottish terriers, Duffie and Tammie, whimpering by the side of the swimming pool. In the pool, Landry found Vera’s lifeless body floating, clad in a nightgown. “I always come in the back way,” Landry told reporters, “But I heard the dogs fretting and I saw that all the lights were on in the house, so I started to investigate. The body was already floating.”

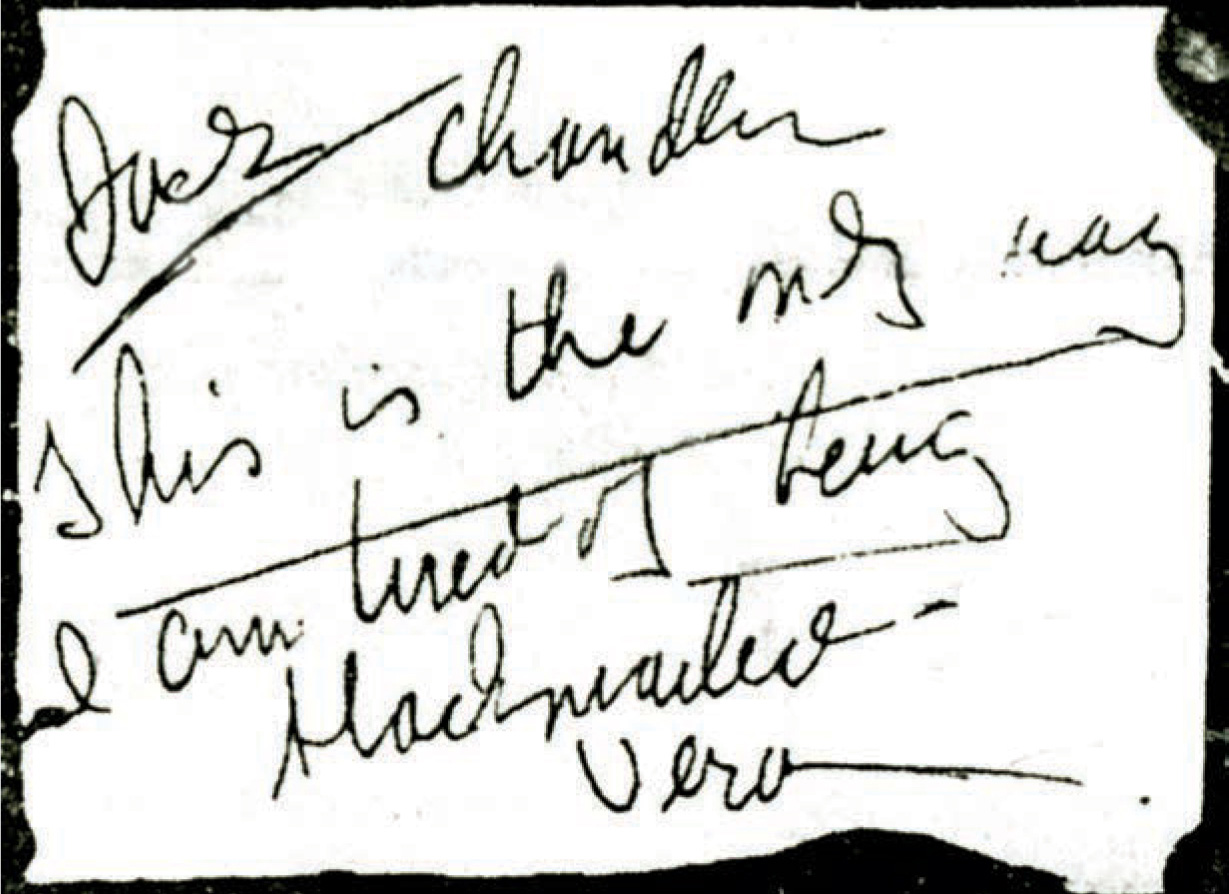

The authorities were summoned. Investigators found two suicide notes, each cryptically referencing some mysterious blackmail. Vera addressed both notes to her husband, referring to him as “Jack Chandler.” One note read, “This is the only way. I am tired of being blackmailed.” The second, written on the back of a torn greeting card, said, “The fortune-teller told me there was only one way to duck the blackmail I’ve paid for 23 years. Death.” An empty bottle of sleeping pills was found in the house. Vera and Jacques both habitually used them. The autopsy showed that Vera died of asphyxia “probably due to drowning.”

Friends of the designer were shocked by her death. Actress Ella Raines had just seen West a short time before in New York. “She was very happy and didn’t seem to have any troubles at all,” Raines told a reporter. Jacques told police a different story. He was not home at the time of his wife’s death, he claimed. The couple had a violent quarrel on Saturday night. Vera had threatened to consult a divorce attorney the following Monday, Jacques said, but that “she had threatened to do that many times before.” Jacques left the house and began to drive to Santa Barbara, but ended up spending the night in his car, never arriving in Santa Barbara. The following afternoon, he returned to Los Angeles and checked into a hotel in Beverly Hills. He learned of his wife’s death when he saw a newspaper headline while at the hotel and “almost collapsed,” he said. Jacques said he believed that her suicide was prompted by their domestic difficulties. He also claimed his wife’s health had not been good.

Vera West

Years earlier, West had gained fame designing costumes for Universal’s horror pictures. Within two years of arriving in Los Angeles in 1926, West began working at Universal and received her first film credit for The Man Who Laughs (1928), starring Conrad Veidt. Universal had been riding a wave of successful horror films that began in 1923 with Lon Chaney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. West supervised the gowns for almost all of the classic Universal horror films, including Dracula (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Son of Frankenstein (1939), The Wolf Man (1941), and Son of Dracula (1943). She also designed for the female stars in Universal’s B-movie thrillers, crime dramas, and westerns.

Marlene Dietrich in Destry Rides Again (1939).

Deanna Durbin in The Amazing Mrs. Holliday (1943).

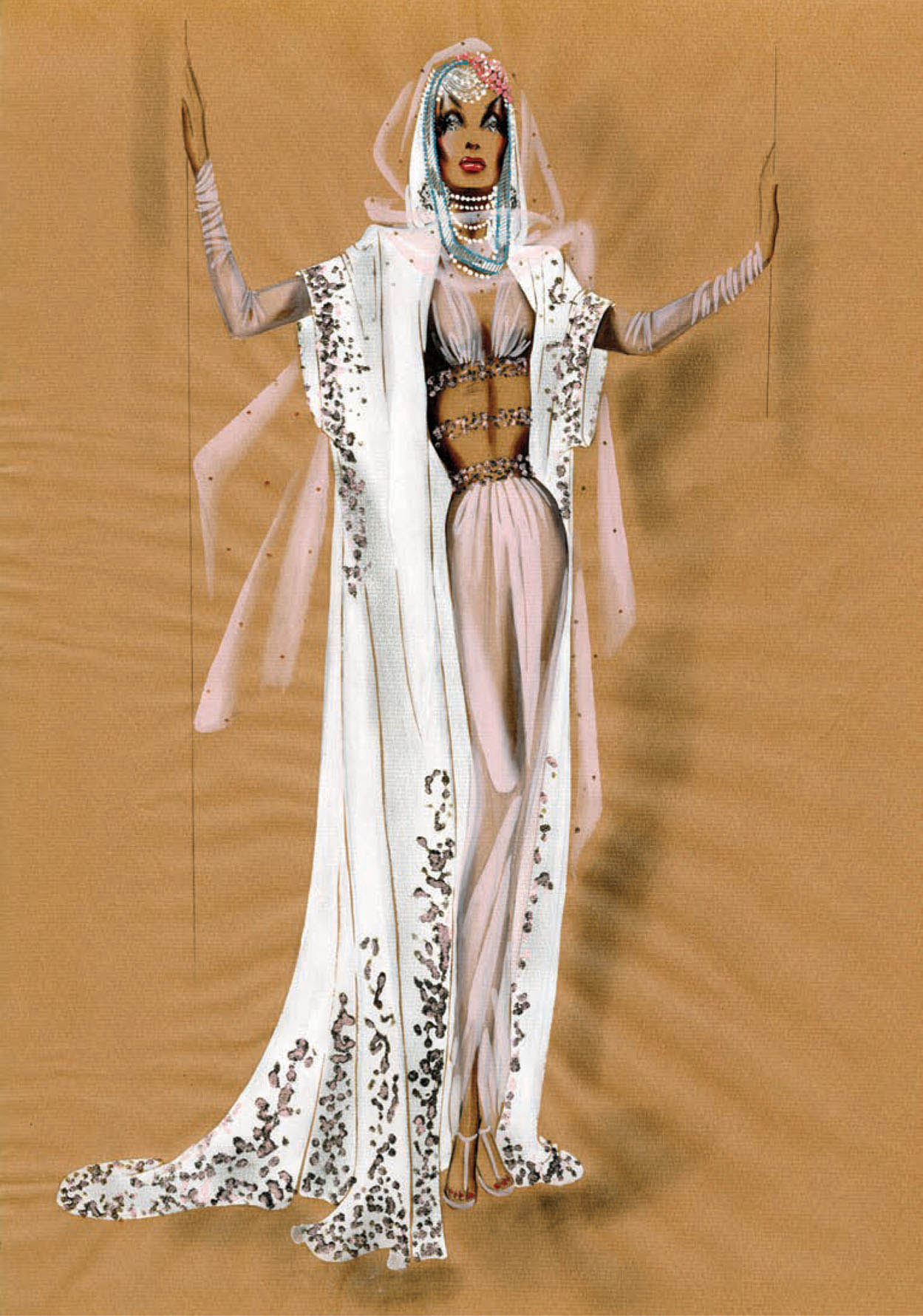

A Vera West sketch for Maria Montez in Sudan (1945).

West was born as Vera Flounders to Emer Lovell and Lillian May Moreland Flounders, on June 26, 1898, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her father was a heating and sheet metal worker. Her mother died when Vera was two years old. Within a couple of years of Lillie’s death, Emer married Clara Ringe, the daughter of a local candy maker. Emer and Clara had two children, Hazel and Emer Jr., though the baby boy died at ten months. When Emer Sr. died at forty-five, on January 14, 1917, West took on the task of supporting her stepmother and sister by working as a dressmaker at a local establishment in Philadelphia.

Vera attended the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design). She grew up in Philadelphia and was working as a dressmaker there in 1920. She married Stephen D. Kille in 1924, and moved to Los Angeles two years later. West’s marriage to Kille, who was employed in the restaurant business, did not last. Whether the couple ever divorced is not known, but when West moved to Hollywood it was sans Kille. By 1930, Vera had married fellow Philadelphian Jacques West, a salesman who eventually owned a cosmetics firm. If West did not divorce Kille, she was a polygamist, as Kille did not die until February 22, 1931, in Philadelphia.

In addition to designing for horror classics during her twenty years at Universal, West also dressed A-list stars. When Marlene Dietrich and Mae West came to Universal, West designed their costumes for Destry Rides Again (1939) and My Little Chickadee (1940), respectively. She dressed Ava Gardner in the Academy Award–winning film The Killers (1946). West’s most successful elegant designs were for the teenage star who arrived at the studio in 1936, and whose films were so financially successful they are credited with saving Universal from bankruptcy: Deanna Durbin. “From the time when Deanna, at thirteen, came to Universal to make her first picture, Three Smart Girls—which was an instantaneous hit—until today, when that charming youngster has registered her fifth hit in a straight row with Three Smart Girls Grow Up, Vera West has designed and created everything which Deanna wears on the screen. In addition, she puts a stamp of approval on Deanna’s personal wardrobe,” Photoplay magazine proclaimed in 1939.

West left Universal in early 1947. After having designed for four hundred films, West was perhaps ready for a change. Or maybe she was disillusioned with the new direction William Goetz, son-in-law of Louis B. Mayer, had decided to take Universal upon becoming head of production in 1946. Upon leaving Universal, West designed a spring collection for a fashion shop in the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.

Jacques told his lawyer, Lyman A. Garber, that his wife “hated the water” and had never learned to swim. She would only go in the water if he was sitting nearby, he claimed. As to the cryptic suicide notes, West told police sergeant R. P. Kealy that his wife suffered from a “persecution complex” and was not being blackmailed. Vera “was always imagining things like that,” he said. “There was absolutely no blackmail involved. She just imagined it.” West said he was well acquainted with his wife’s financial matters and that there was no evidence she had been paying blackmail, but that her behavior had become more erratic. Police found two notes written by Jacques titled “gremlins of my wife’s imagination.”

Designer Yvonne Wood told friends various theories as to West’s end. At times, Wood claimed that West had been murdered, and that her death was made to look like a suicide. But Wood could never identify a plausible motive for murder. “Nobody could understand why anyone would want to kill her. Nobody profited from it financially,” Hollywood historian David Chierichetti said. Wood herself admitted that West was a kind soul and well liked, with no known enemies. At other times, Wood speculated that suicide was plausible, and that West’s alcohol problem may have led her to take her own life.

Investigators concluded that the blackmail references were “hallucinations” resulting from West’s supposed neurotic condition. But the investigation appeared superficial, at best, as evidenced by the lack of meaningful discussions in the press regarding West’s mysterious pre-Hollywood history and the details suggested in her suicide notes. Did investigators know about West’s previous marriage to Stephen Kille twenty-three years earlier, which corresponded exactly to the time West said the blackmail had begun? Many of West’s claims regarding her past accomplishments appeared fabricated. Who knew that? And what would publicizing the falsehoods have meant to West, given her subsequent successful career at Universal? And was West’s choice of suicide by drowning not shockingly improbable, given her morbid fear of water? Why did Jacques take an aborted trip to Santa Barbara, claiming instead to have stopped to spend the night in his car, an alibi that likely defied verification? Were earlier reports that Jacques was away on business at the time of the death a mistake by reporters, or a blunder that he abandoned when he realized that he could not manufacture evidence for such a trip? Did anyone review West’s financial records to see if sums had mysteriously disappeared to hush a blackmailer, or did the police simply accept Jacques’s word on the subject? Why were West’s friends and colleagues unable to corroborate Jacques’s claim that West was “always imaging things”? And no conclusion was ever drawn as to who the mysterious fortune-teller was who encouraged West to kill herself, if one actually existed.

One of the suicide notes left by Vera West.

Following Vera’s death, Jacques West, who used aliases during his life, disappeared, but not before having the house on Bluebell Avenue where the death occurred demolished, and the land sold to a developer who subsequently built three new homes on the former West homestead.