On November 15, 1962, Irene Gibbons checked into the Knickerbocker Hotel, a hotspot where movie stars and Hollywood insiders alike hobnobbed regularly. She used a fake name and requested a room on the eleventh floor.

It was the Thursday of Fashion Week in Los Angeles, and her new collection had been well received just two days before. Soon after checking in, Irene opened the first of two bottles of vodka she had brought with her and began to compose two notes. “I am sorry to do this in this manner,” she wrote. “Please see that Eliot is taken care of. Take care of the business and get someone very good to design. Love to all, Irene.” In the second note, she tried to excuse her alcohol consumption to the other hotel guests. “Neighbors,” she wrote, “Sorry I had to drink so much to get the courage to do this.”

After almost finishing the second bottle of vodka, Irene removed the screen from her hotel bathroom window just after 3 o’clock in the afternoon. The sixty-one-year-old designer leaped from the eleventh floor of the hotel, landing on the roof of the hotel’s extended ground floor. The coroner estimated that she lingered for several minutes before dying from “severe internal crushing injuries.” Los Angeles police would later report that Irene had attempted to slash her wrists before jumping, though her death certificate makes no reference to such wounds.

The fashion world could not understand why the woman who had brought so much exquisite loveliness to the world had left it prematurely. But Hollywood insiders were less perplexed. “I knew it was coming,” Irene’s assistant, Adele Balkan, said. “Anybody who knew her knew it was coming. I don’t think it was the first attempt. She wouldn’t or couldn’t help herself.” During a forty-year career that most designers could only envy, Irene had her own salon in Los Angeles’ top luxury department store, and dressed Hollywood’s leading ladies in more than one hundred films. “She was a woman of great taste and great elegance and great talent,” Balkan said, “and it all went down the drain.”

She was born Irene Marie Lentz on December 15, 1901, in Brookings, South Dakota, to Emil and Maude Watters Lentz. Her family settled in Baker, Montana, in 1910, where Maude ran a general store and Emil dabbled in small-town politics. As a young girl, Irene dreamed of becoming a concert pianist; she mastered classical pieces by Debussy, Handel, Liszt, and Bach.

After high school graduation in 1919, Irene moved to Los Angeles with her mother and little brother, Kline. Her father also moved to Los Angeles, though he apparently never lived with the family again. Why the family moved west is uncertain. Irene later claimed that a drought had devastated her parents’ cattle ranch, but this story contradicted her claim that she grew up in town working in her parents’ general store. Upon their arrival in California, the Lentzes lived at 291 South Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles. Maude cleaned hotel rooms, and Irene worked as a saleslady in a drugstore. It was there in 1921 that she met handsome F. Richard Jones, a director at Mack Sennett’s Keystone studio. The couple began dating. The initial romance ended quickly because Irene could not tolerate Jones’s philandering. But he remained a helpful business contact. Because of Jones, Lentz worked as an extra at Keystone. A year later, Jones arranged for Lentz to work as a production assistant at Keystone, as well as to act in some films.

Still remembering her childhood dream of being a concert pianist, Irene enrolled in courses in music theory and composition at the University of Southern California. “Designing as a career never occurred to me then,” she said. “I enjoyed planning my own wardrobes and helping with those of my friends, but making a business of it never did enter my mind. Instead, my entire ambitions were to be a concert pianist.” A hometown friend persuaded Irene to take a class with her at Wolfe School of Design. “I agreed, not with a great deal of desire to be a designer, but simply to please her,” Irene said. “After a few days, however, I was convinced that designing was the thing I wanted most to do.”

A young Irene Lentz appears with Ben Turpin in the Keystone comedy Ten Dollars or Ten Days (1924).

Irene graduated from Wolfe in 1926, and with Jones’s financial assistance, she opened a small dress shop near the University of Southern California. Her piano became part of the shop’s decor. The store catered to students, and while the apparel was of good quality, Irene purposely eschewed expensive clothing. “The campus shop was a great success from the beginning,” Irene said. “The dresses were cheap and I do think they had a certain flair.” Irene would later claim, tongue-in-cheek, that her shop became a success because it was the only place on campus where girls could smoke. “Cigarettes were strictly against the rules everywhere else,” Irene said. “So I always had a shop full of prospective clients, smoking. The place was so full of smoke so much of the time that my doctor would not believe it when I told him I did not smoke.”

Soon ladies from the Wilshire District, Beverly Hills, and Hollywood were coming to her college shop. Dolores del Rio walked in one day and bought an evening gown for $45. “Many a woman would not have told a soul where she’d bought that dress,” Irene said. “But Dolores told everybody she knew. After that, I got plenty of movie trade.” Lupe Vélez soon became one of Irene’s best customers. Consistent with her apparent innate drive to be in the spotlight, the “Mexican Spitfire” insisted on trying on dresses in the shop’s main room, near the windows, rather than using a fitting room. “She always had a gallery,” Irene said.

After the success of the first small store, Irene opened a larger salon on Highland Avenue in Los Angeles. A little over a year later, and after nearly a decade of on-again, off-again romance, Irene married Jones on September 20, 1929. With business at the store going well, a bright future seemed assured for the couple. Jones was becoming one of Hollywood’s most successful filmmakers, directing Douglas Fairbanks in The Gaucho (1927) and Ronald Colman in the early talkie Bulldog Drummond (1929). Tragically, and with little warning, Jones became ill and died of tuberculosis on December 14, 1930. His loss so devastated Irene that she never fully recovered emotionally. Even decades later, Irene would still openly lament his loss.

Irene closed her shop and went to Paris to visit her friend, actress Alice Terry. While there, Irene first learned about couture design by observing the local fashion houses. She returned to Los Angeles and opened a new shop on Sunset Boulevard in August 1931.

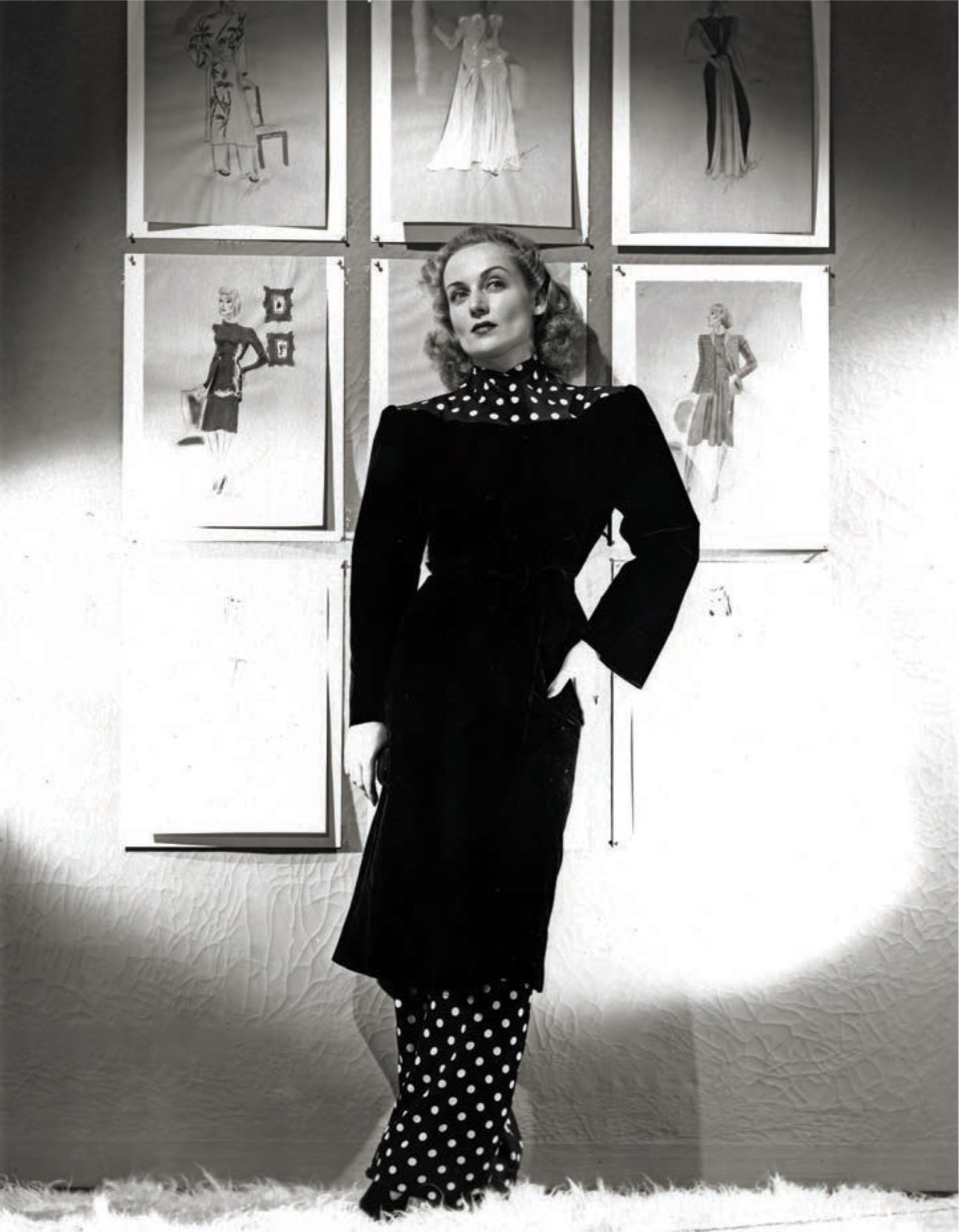

Ann Hodge, general manager at Bullocks Wilshire, the top luxury department store in Los Angeles, recognized the profit potential of bringing Irene’s burgeoning celebrity clientele into her company. She orchestrated the opening of Irene’s custom French-style salon in the store in 1933. Irene’s clientele included some of Hollywood’s biggest names—Irene Dunne, Helen Chandler, Dolores del Rio, Joan Bennett, Joan Crawford, Jeanette MacDonald, Norma Shearer, Jean Harlow, and Carole Lombard.

The local press was impressed. “Those of us who have watched Irene growing up, who have noted her progress each year, who have been amazed at her patience and diligence and energy, who have always believed in her artistry, are now pleased to make a low and sweeping bow before her upon her debut as one of the world’s leading designers,” one fashion critic wrote.

In 1934, Del Rio introduced Irene to her brother-in-law, Eliot Gibbons, a newspaper reporter and brother of MGM art director Cedric Gibbons. Irene and Gibbons shared a fondness of sports and flying, and Gibbons helped Irene obtain her pilot license. The couple married on September 27, 1935. That same year, Gibbons took a job as a screenwriter at MGM. The newlyweds had their challenges early on. Irene suffered a miscarriage in 1937 when she took a fall. Then in 1938, the couple made headlines when they were lost in deep snow drifts on the ski slopes of Badger Pass in Yosemite National Park for forty-eight hours. Fifty forest rangers and skiers searched for two days for the missing couple. The rangers found Eliot first, as he had set out for help. He led them back to Irene, who was found huddled at a campfire at the Bridal Veil Creek area. She had a sprained ankle, and rangers had to carry her out of the valley on a makeshift stretcher.

With Irene’s customer base including actresses, the appearance of her gowns on-screen were inevitable. In 1932, they were featured in The Animal Kingdom with Ann Harding and Leslie Howard. Del Rio used her clothes in Flying Down to Rio (1933), and requested that RKO use Irene for all of her movies.

“When she has a showing of her creations, all of movieland is on hand,” Jackie Martin wrote of one of Irene’s 1939 showings at Bullocks Wilshire. “It was interesting to sit back and watch them arrive. First, the simply gorgeous Dolores del Rio. Then Paulette Goddard. Then quiet, unassuming Sandra Shaw—Mrs. Gary Cooper. Loretta Young. Oh oh—here comes La Dietrich. And Mrs. Leopold Stokowski, wife of the orchestra leader. Everybody was there but Garbo. While the models paraded around, the guests were served tea. Then, when it was over, what a rush down to Irene’s beautiful salon! Glamour girls on the run—to reach Irene and get that simply divine creation before Marlene could!” Garbo had attended a fashion show the year before, concealed from the rest of the attendees by a door. The models paraded by for her exclusive view after they had exhibited their gowns for the rest of the patrons.

In the early 1940s, Irene was contributing gowns to nearly every film made by Marlene Dietrich, Rosalind Russell, and Claudette Colbert. So when Adrian left MGM and Robert Kalloch did not work out as his replacement, Louis B. Mayer’s wife, Margaret, suggested that he consider Irene for the studio. Although Irene was unhappy with her financial arrangement with Bullocks Wilshire, Mayer’s first offer in November 1941 did not impress her. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December, Mayer felt his options narrowing. He met with Irene again. He agreed to her salary demands and allowed her to continue to design for a few private clients. Irene took six months to finish at Bullocks Wilshire and moved to MGM on July 1, 1942. “You’re not going to like it because you’re not going to be as independent as you are here,” Balkan told Irene when she left Bullocks Wilshire. Balkan’s advice was well informed; she had previously worked at studios.

Some wardrobe personnel instantly resented Irene, believing nepotism played a role in her hire at MGM, as her husband and brother-in-law both already worked there. Irene brought in Marion Herwood and Kay Dean to work on the period films. J. Arlington Valles and Gile Steele were already designing the men’s costumes. Irene brought in Walter Plunkett because of his ability to design both period and men’s costumes.

Loretta Young in He Stayed for Breakfast (1940).

Claudette Colbert in Midnight (1939).

Carole Lombard in Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941).

For Gaslight (1944), Irene lifted the period designs almost entirely from research, even posing with director George Cukor holding a copy of Godey’s Lady’s Book, documenting the source of the designs. “She’s a person who cares nothing about clothes,” Irene said of Gaslight star Ingrid Bergman. “She always dresses simply, and so she should. I wouldn’t want to change her, not in any way. Everyone adores her. But when she stepped into the costumes of Gaslight, those lovely clothes of the 1880s, she looked as though she had always worn just such clothes. She was exactly right and so beautiful.” Diana Vreeland, editor of Harper’s Bazaar, was so impressed with the clothes from Gaslight, that she sent Irene a letter in May of 1944. “Dear Miss Irene,” it read. “The other night I went to see Gaslight. I cannot tell you how much I enjoyed it, but most of all I want to tell you how wonderfully you have dressed Bergman. She was so superbly elegant—all the clothes, hats, details, were so perfect that I wanted to tell you, so that you would know how very much appreciated these clothes are as everybody that has seen the picture remarks about them and feels about them the same way I do.”

As a designer, Irene found some actresses more desirable as a model for her creations than others. Joan Crawford and Esther Williams had broad shoulders and narrow hips and could wear Irene’s suits better than, say, Donna Reed, who Irene assigned to her staff. “Those women had their own particular styles,” Irene said. Irene assigned projects based on the script and which stars were involved in the project. She was proprietary over certain actresses, including Lana Turner and Barbara Stanwyck. The latter bestowed significant trust in Irene’s style sense. Not until Irene urged her to do so did Stanwyck cut her long gray hair, even though long hair had been out of style for several years.

In September of 1946, Irene received the Neiman Marcus Award for Distinguished Service in the Field of Fashion. Receiving notification of the award early in the year may have rekindled Irene’s desire to return to retail business when her contract with MGM expired. In January 1946, Irene asked Mayer if he would be willing to back her in the private venture. He refused, as she expected he would, but his refusal opened the way for Irene to approach investors elsewhere.

Irene secured financing for Irene Inc., from twenty-five department stores in exchange for the exclusive right to sell her clothes in their respective cities. She announced the news to the press before securing Mayer’s permission. But the press reported that the venture was with Mayer’s blessing, and that Irene would be cutting her studio design duties to eight to ten films a year. “This the kind of deal that Adrian wanted years ago,” Hedda Hopper wrote, “but Metro wouldn’t give. So he formed his own company, which has been a fabulous success.”

Fred Astaire and Rita Hayworth in You Were Never Lovelier (1942).

Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight (1944).

Director George Cukor and Irene look over a copy of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the inspiration for many of Irene’s designs for Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight.

Located at 3550 Hayden Avenue in Culver City, Irene Inc. was a three-minute drive from MGM’s lot. Irene arrived at her factory at 7:30 a.m., and then commuted to MGM at 9:00 a.m. She took her lunch at the factory, then headed back to the studio to finish her day. During her tenure at MGM, Irene’s long-hidden problem with drinking became more and more public. Irene had shown signs of alcoholism after the death of her first husband, and it remained an open secret among her friends and colleagues for years.

During World War II, Eliot Gibbons served as a captain in the U.S. Ferry Command. While Gibbons was absent on active duty, Irene took a small apartment in Westwood Village. Long periods went by when Irene had no idea where Gibbons was stationed. A chasm grew between them after he began an affair upon his return to Los Angeles. Irene’s drinking increased, and late in 1946, she was arrested for drunk driving. Mayer kept the incident out of the newspapers and ordered Irene into a clinic. The treatment had little effect.

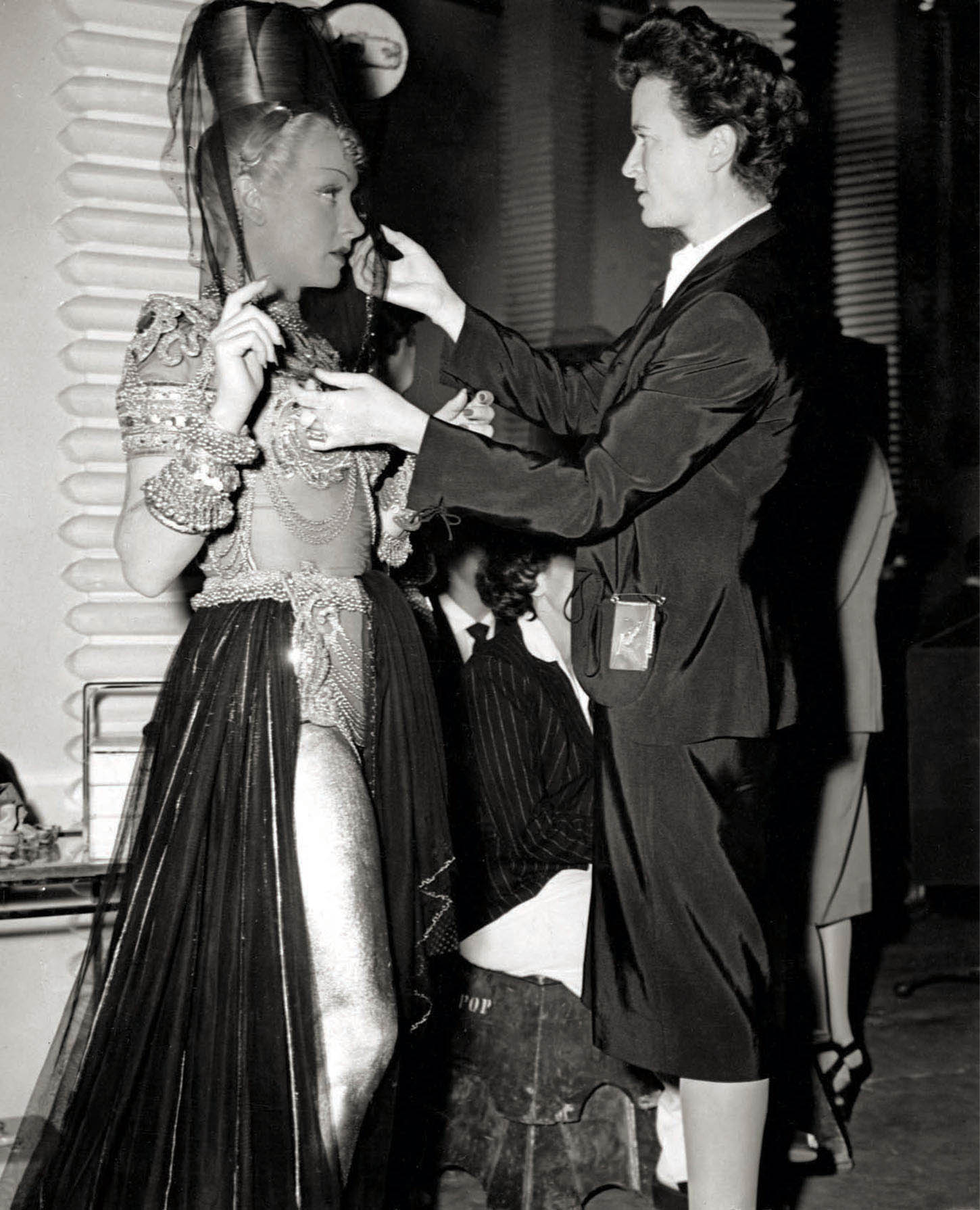

Marlene Dietrich and Irene on the set of Kismet (1944).

Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946).

In 1949, while working on Adam’s Rib with Katharine Hepburn, tensions escalated quickly that resulted in Irene’s dismissal from MGM. Hepburn and Irene had worked together previously on Without Love (1945) and Undercurrent (1946). Each time, Hepburn had rejected a great number of Irene’s ideas and seemed hostile toward the designer. Irene never understood the actress’s enmity. Hepburn even went so far as to hide Irene’s designs when she appeared on-screen, covering one outfit with a bulky sweater and pulling a sheet up to her chin in another. When Hepburn arrived for a fitting in May of 1949 and found Irene absent from her office, she complained to MGM’s New York office. Irene’s drinking and side business were preventing her from executing her job properly, Hepburn contended. The studio agreed. Irene’s contract was terminated, with Mayer citing the morals clause, which allowed the studio to fire an employee for moral turpitude. Irene later told Travis Banton she had believed that going to MGM had been a mistake. “There was nothing I could say,” Banton said. “She was right.”

An Irene sketch for Judy Garland in In the Good Old Summertime (1949).

Irene continued designing her collections for Irene Inc. and occasionally returned to films, designing for Doris Day in Midnight Lace (1960) and Lover Come Back (1961). Day had requested Irene for her films because of her great respect for Irene and appreciation of their friendship. Still, Day was anything but deferential to Irene. “Doris Day got her way, regardless,” said Balkan, who returned to Irene to help her with the Day films. “Doris knew what Doris needed. Those were the days of the sleeveless dresses, and Doris knew that the sleeveless part should not be at the edge of her shoulder, but inside of it. It looked better. Doris was right, and Irene knew it in the end, but it’s pretty hard to be the authority and then have it stepped on.”

The 1960s brought nothing but heartache for Irene. Her estranged husband suffered several strokes, requiring his placement in a skilled nursing facility. Two years before her fatal plunge, Irene incurred permanent nerve damage to her face when she fell asleep against an electric blanket. A decade after the suicide, Day wrote in her autobiography that Irene had confided in her that she was in love with Gary Cooper. Day did not know whether the feelings had been returned or if the two ever had an affair. Irene had, in fact, been a close friend of the Cooper family and was devastated when he died of cancer on May 13, 1961.

Balkan blamed Irene Inc. for much of the designer’s unhappiness. “The demands wore her down. The business wasn’t what she wanted anymore,” Balkan said. “The people who worked with her would scream at her when she’d get drunk because they were tired of it. They’d had enough of it too. She wouldn’t go to Alcoholics Anonymous, naturally she just wasn’t going to face it. She couldn’t face the fact that she’d get up and tell people she was an alcoholic when the whole city knew it anyhow.”

After her suicide, Alden Olds, president of Irene Inc., said the designer had been under “terrific strain” for some time. “She had been in ill health for about two years, and because of ill health, she did what she did, I’m convinced. She was a stalwart girl with a great deal of love for life, and this thing was just too much for her to bear.”

“There is really nothing one can say about the sad end to the life of Irene, other than to repeat what many others have already said,” a friend wrote to Alden Olds. “Unfortunately, in so many cases, it seems a truism that the tragedies of everyday life seem to haunt those whose basic qualities of character are above average. Somehow unhappiness in this sense rarely bothers the rogue and the opportunist. I guess this is just one of the paradoxes of creation. Yet, in a way, Irene, in spite of all the periods of depression, was an optimist and always looked to the future, perhaps at times with trepidation but always with hope.”

Irene on the set of In the Good Old Summertime with a young Liza Minnelli.

Jane Russell in The Revolt of Mamie Stover (1956).