Edith Head received more Oscar nominations—a total of thirty-five—and Oscar wins—a total of eight—than any other designer in the history of Hollywood. Yet Head never thought of herself as a great costume designer.

She had an intelligent approach to design, she would concede. For her, the necessities of film came first. She was more interested in making sure that the actors had what they needed to get their job done, rather than creating something that would be a big coup for herself as a designer. Travis Banton, Adrian, and Irene may have had their distinctive looks, but Head believed there was no particular “Edith Head look.” She prided herself that directors knew she could interpret a script without suddenly imposing a “great Edith Head dress” on them.

Head had the longest career of any designer of the Golden Age, working right up until her death in 1981. She never set out to be a costume designer or even to work in the motion picture business, though her father, Max Posenor, had been a haberdasher. He had emigrated from Prussia in 1876. Head’s mother, Anna Levy, was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1874. Edith Claire Posenor was born on October 28, 1897, in San Bernardino, California, where Max had his men’s clothing shop. The Posenor marriage ended so quickly that Head could not remember her parents being married. Anna married mining engineer Frank J. Spare on January 21, 1902, in Chicago. The family moved from mining town to mining town so often that, as an adult, Head could not recall all the towns in which she had lived, though she called Searchlight, Nevada, her hometown because she spent most of her childhood there.

Spare made a decent living, but the family was hardly well off. Still, Head’s mother looked after the family, and Head was always well dressed. As a young girl, Head crafted dolls out of the pliable greasewood that grew in the desert. She constantly collected scraps of fabric to dress her dolls and to help decorate her makeshift dollhouse of old wooden boxes. Her bag of scrap fabrics was her most treasured possession.

Some of Head’s front teeth did not grow in properly, and classmates nicknamed Head “Beaver.” Head stopped smiling and became more introverted. Even after having her teeth fixed as an adult, she politely declined to smile for photographers.

In 1914, Anna decided the nomadic life was no place for her daughter, and brought her to Los Angeles to attend high school. Head went on to major in languages at the University of California Berkeley, and earned a master’s in French from Stanford University. When a French teacher at the Bishop’s School in La Jolla hastily returned to France due to a family emergency, Head accepted her first teaching assignment. Next Head taught art at the Hollywood School for Girls, where daughters of movie stars and industry personnel comprised almost the entire student body. She never considered herself artistic; desert mining towns had offered little opportunities for exposure to the arts. To stay one step ahead of her students, Head took art classes at night at Otis College of Art and Design and Chouinard Art Institute. While attending Chouinard, she met traveling salesman Charles Head, the brother of a classmate. They married in 1923. Although the marriage did not last, Head retained her husband’s name professionally for the rest of her life.

As an art instructor at the Hollywood School for Girls, Head chaperoned students on field trips to Paramount, where they watched Cecil B. DeMille work on large-scale scenes. DeMille’s daughters were enrolled at Head’s school, and DeMille sat on the school’s board of trustees. To supplement her income during the summer, Head responded to designer Howard Greer’s ad looking for a sketch artist for a new DeMille film. Although her experiences as a field trip sponsor gave her the confidence to apply for the job, she lacked the confidence in her own artistic ability to submit an honest application for the position. Instead Head “borrowed” other students’ drawings from Chouinard and presented them to Greer as her own. Had Head known just how frantically Greer needed designers, she probably would not have taken such a desperate tact. With the DeMille project requiring hundreds of costumes, Greer did not have the luxury of turning down any of the fifteen applicants.

Betty Grable in an Edith Head design for This Way Please (1937).

Claudette Colbert in Zaza (1938).

Head’s versatility immediately impressed Greer, so when he noticed that she seemed ill-at-ease at her drawing board, he tried to reassure her.

“Don’t be upset,” Greer said. “It won’t take long to get the hang of things.”

“I’m not worried about that,” Head responded, “but I have the most awful confession to make. You see, when I was faced with my first interview, I was suddenly seized with panic. I was afraid that if I didn’t have a lot of wonderful sketches, I’d never get the job.”

“But they were wonderful. All of them!” Greer said.

“That’s just it,” Head confessed. “They weren’t any of them mine! I just went through the art school where I’ve been studying and picked up everybody’s sketches I could lay my hands on!”

Greer did not fire Head. “She might easily have saved her breath and her confession,” Greer later wrote, “for her own talents soon proved she was more than worthy for the job.”

Greer initially gave all of his new hires the same assignment. With all of his designers sitting together in one room, Greer explained that DeMille needed a woman’s riding habit. But DeMille did not want just any riding habit that could be bought in a store. He wanted something that would make the audience gasp. Head’s design, a gold riding habit with matching gold boots, pleased DeMille. She held on to her job, the only one of her group who did. Head may not have been the best artist in the lot, but she was older, better educated, better traveled, and had the real-world experience of teaching school. She also worked harder than most. If Greer asked for one sketch, she would do three or four. And as a skilled mimic, she quickly learned to sketch artistically like Greer. Because of Head’s ability to speak Spanish, Greer came to rely on her help in the workroom.

After Walter Wanger brought Travis Banton to Paramount for The Dressmaker from Paris (1925), Head became both his and Greer’s assistant. Banton and Greer split up the roster of Paramount stars between them, with Greer designing for Pola Negri and Banton taking Florence Vidor and Evelyn Brent. When Greer left Paramount in 1927 to open his own salon, Head was given more responsibility. Banton continued to design for the films’ stars, with Head dressing the other actresses in the films. She designed for Mary Carlisle, Leila Hyams, Joan Bennett, Gracie Allen, and Martha Raye.

Edith Head and Dorothy Lamour during the making of My Favorite Brunette (1947).

Head was first assigned to design for Mae West in She Done Him Wrong (1933), when Banton was away in Paris. Head soon found herself designing with West, rather than for her. “Make the clothes loose enough to prove I’m a lady, but tight enough to show ’em I’m a woman,” West told Head. West wanted tight black dresses, sequins, plumes of feathers, and lots of jewelry. For as often as West ran afoul of censors, she almost never showed cleavage or leg.

When Paramount did not renew Banton’s contract in 1937, Head eventually assumed his position as head designer. Some stars believed that Head had sabotaged Banton and refused to work with her. That perception was unwarranted. Head had desperately wanted Banton to stay, as he guaranteed her job security. She was not the obvious choice as a replacement. Paramount initially considered Ernst Dryden to replace Banton; Head did not assume the position for nearly two years.

Barbara Stanwyck in Ball of Fire (1941).

Veronica Lake in This Gun for Hire (1942).

Barbara Stanwyck in Flesh and Fantasy (1943).

In her new position, Head influenced fashion. She first wrapped a young Dorothy Lamour in a sarong for The Jungle Princess (1936). With the success of Jungle Princess, scriptwriters labored to find any excuse to keep Lamour in a sarong. During the rest of the 1930s and into the ’40s, Lamour appeared in road pictures with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, and sarongs and sarong-inspired clothing sold well across the nation.

For The Lady Eve (1941), Head corrected a figure problem that had plagued Stanwyck in previous movies and had kept her from making more high-fashion films. Head compensated for Stanwyck’s long waist and low-slung rear by building her skirts high on her waist. Stanwyck’s long waist was actually an asset, Head believed, and made Stanwyck look more elegant.

Head divorced Charles Head in 1938 and married art director Wiard “Bill” Ihnen on September 8, 1940. The couple eventually moved into a rambling Spanish-style house in Beverly Hills, which they called Casa Ladera. In the mid-1940s, Head joined the panel of Art Linkletter’s House Party radio show on CBS. With an afternoon timeslot, the show sought to dispense helpful information to housewives. Naturally fashion played a part. Linkletter initially found Head painfully shy. “She came into my office,” Linkletter said, “and I thought, ‘Oh my, what are we going to do with this quiet, shy, reticent little woman wearing very unglamorous clothes and glasses and kind of a dull hat?’” With Linkletter’s able coaching, Head became popular with listeners as she helped them simplify their look and dress well on any budget. When House Party made the transition to television, Head became the most recognized costume designer in the public eye. She appeared on the show for its entire fifteen-year run.

Head won her first Oscar for The Heiress (1949), in which Olivia de Havilland played an awkward young woman being courted by Morris, a handsome golddigger, played by Montgomery Clift. Director William Wyler insisted on historical accuracy in the costumes for the mid-nineteenth century tale. Head and de Havilland visited museums and studied original period clothing together. De Havilland’s wardrobe expertly reflected the progression of her character, Catherine, throughout the story.

Ingrid Bergman in Notorious (1946).

Head’s second Oscar came for a movie that she would not have normally designed. All About Eve (1950) was a 20th Century-Fox production. The Paramount designer was brought on when Bette Davis replaced Claudette Colbert as Margo Channing. “Bette walks in here like a small, disciplined cyclone,” Head said of the actress. “You don’t discuss details with Bette. She shows you how she is going to do the part, how she is going to throw herself on the bed, sit on the desk, or whirl around and walk out in a huff. ‘That,’ says Bette, ‘is the way I want the clothes to act.’”

(l-r) Edith Head, Alma Reville, Alfred Hitchcock, and Ingrid Bergman discuss a design for Notorious (1946).

Davis’s dress for one of her most famous scenes in Eve unintentionally deviated from Head’s original design. For the party scene in All About Eve, Head designed a brown silk dress trimmed in sable with a squared neckline. Charles Le Maire had designed a similar dress for Anne Baxter for the same scene. On the day of filming, Head’s dress slipped off Davis’s shoulders when she tried it on. The dress had been measured incorrectly. As Head summoned her courage and prepared to tell director Joseph Mankiewicz that production would be delayed, Davis stopped her. Looking in the mirror, she asked Head if perhaps the dress was not better with the shoulders exposed. Head added a few stitches to keep the dress from slipping further, and off Davis went to utter the legendary line, “Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

Though Gloria Swanson had been one of Paramount’s biggest stars when Head began working at the studio in 1924, Head did not design for her until Sunset Boulevard (1950). Even though Swanson’s character, Norma Desmond, was a delusional has-been, director Billy Wilder did not want her to appear literally stuck in the past. Head gave Norma up-to-date fashions, but included a few touches demonstrating that Desmond had not entirely moved on from her silent-screen heyday. Head included oversize accessories and a silk lounging robe printed in leopard skin.

Director George Stevens told Head to strive for realism in A Place in the Sun (1951). He wanted the costumes to be true to real-world people, rather than Hollywood’s caricature of stereotypes. For Elizabeth Taylor, he challenged Head to design an honest look of a young, very wealthy girl, and for Shelley Winters, a convincing factory worker’s wardrobe. Head’s design for Taylor’s gown, having six layers of white net over pale mint green taffeta, and a white velvet bodice covered in white velvet violets with green centers became the fashion hit of the season.

A costume sketch for Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah (1949).

Costume sketches by Edith Head for Grace Kelly in To Catch a Thief (1955).

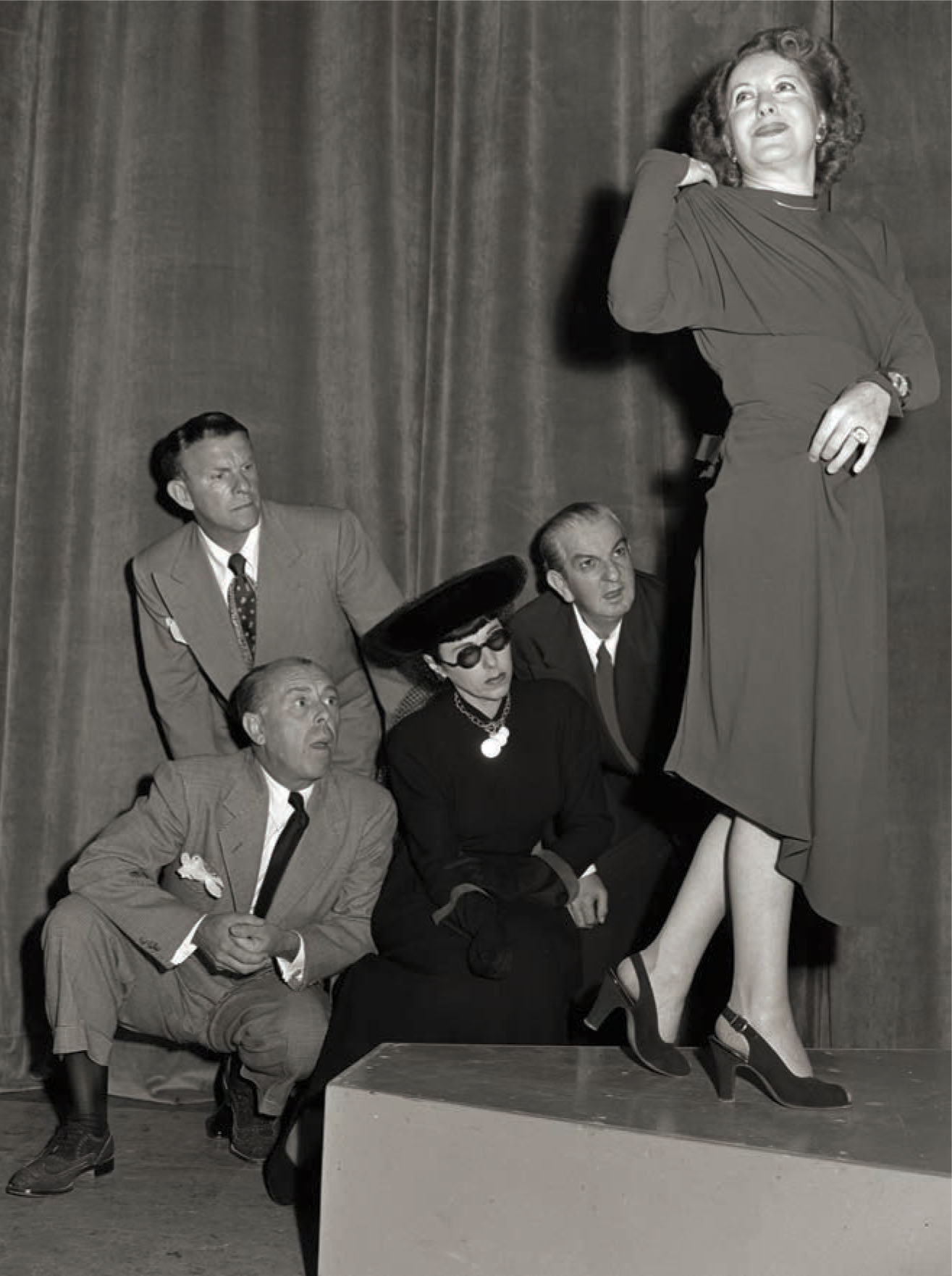

With George Burns behind them, costume designers Howard Greer, Edith Head, and Orry-Kelly discuss the length of the skirt Gracie Allen wears while recording a segment of the Maxwell House Coffee Time Starring Burns and Allen radio program in 1947.

Barbara Stanwyck in The Other Love (1947).

William Holden and Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Olivia de Havilland in The Heiress (1949).

Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Audrey Hepburn’s boyish figure defied America’s prevailing view of beauty when she arrived in Hollywood. When she was cast in Roman Holiday (1953), she let Head know that she liked her long neck and had no intention of hiding it. Head used a long torso brocade ball gown with a wide off-shoulder collar to help the audience understand that Hepburn’s character feels restricted by her royal duties. In Billy Wilder’s Sabrina (1954), Hepburn asked that gowns from fledgling designer Hubert de Givenchy be used for her character upon her return from Paris. At the time, Head was unhappy that Wilder indulged Hepburn and used Givenchy gowns. But in later years, she was more contrite, believing that ultimately it helped the film. Givenchy was not credited in the film, and Head won the Oscar for Sabrina, which resulted in much criticism for Head.

For The Country Girl (1954), director George Seaton liked to underemphasize clothes, so they only serve to build character. “Though we often had to work hard with some stars to create an illusion of great beauty,” Head remembered later, “I had to take one of the most beautiful women in the world and make her look plain and drab.” Making Grace Kelly appear plain was not easy. “It was very difficult to dress down all her good points,” Head said. “But I did even that. That’s really illusion in reverse!” Head had worked with Kelly earlier, on Rear Window (1954). Kelly had been a model, and Head found her a woman of good breeding and taste. Kelly was partial to pastels and white. She abhorred strong colors, which was fortunate because director Alfred Hitchcock only liked them if they were part of the story. “Hitchcock is the only person who writes a script to such detail that you really could go ahead and almost make the clothes without discussing them,” Head said. “It’s so completely lucid, like, ‘she’s in a black coat, she has a black hat, and she wears black glasses.’”

Elizabeth Taylor in Elephant Walk (1954).

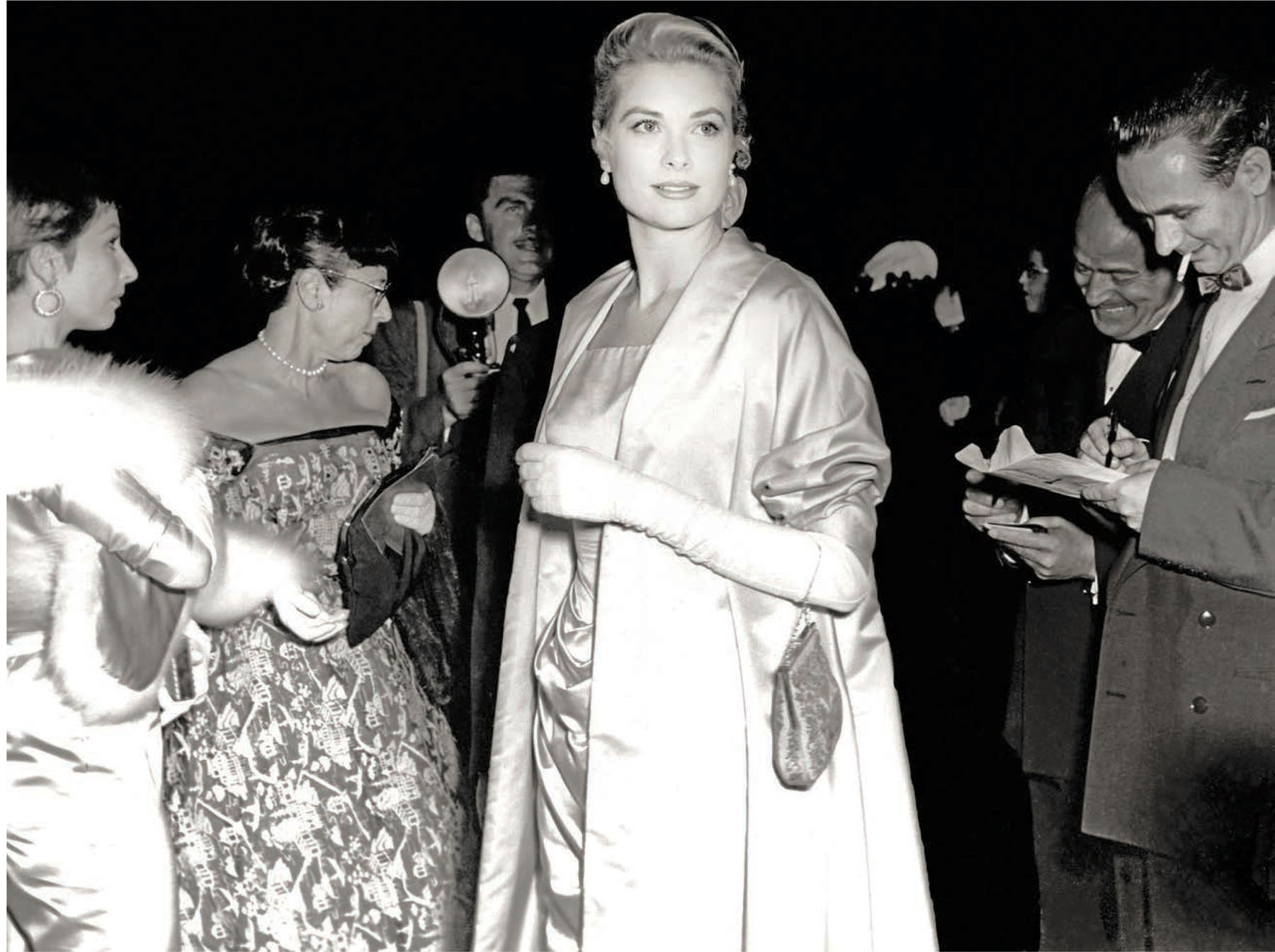

Grace Kelly arrives at the 1955 Oscar ceremony wearing an Edith Head ensemble. Edith can be seen in the background.

Kelly proved to be Hitchcock’s perfect muse. “I’m not interested in sharing a Marilyn Monroe-type,” Hitchcock once said of Kelly. Hitchcock’s mother, Emma, had been an impeccable dresser and had given the director strong Victorian sensibilities. He believed in letting the audience discover that there might be a volcano under a glacier. For To Catch a Thief (1955), Head accentuated Kelly’s glacial qualities through a blue chiffon dress with spaghetti straps, and then a white chiffon dress. As Grace’s character thaws, her clothes become brighter until finally at the end, she wears a gold ball gown, which Hitchcock had requested to make her look like a fairy princess.

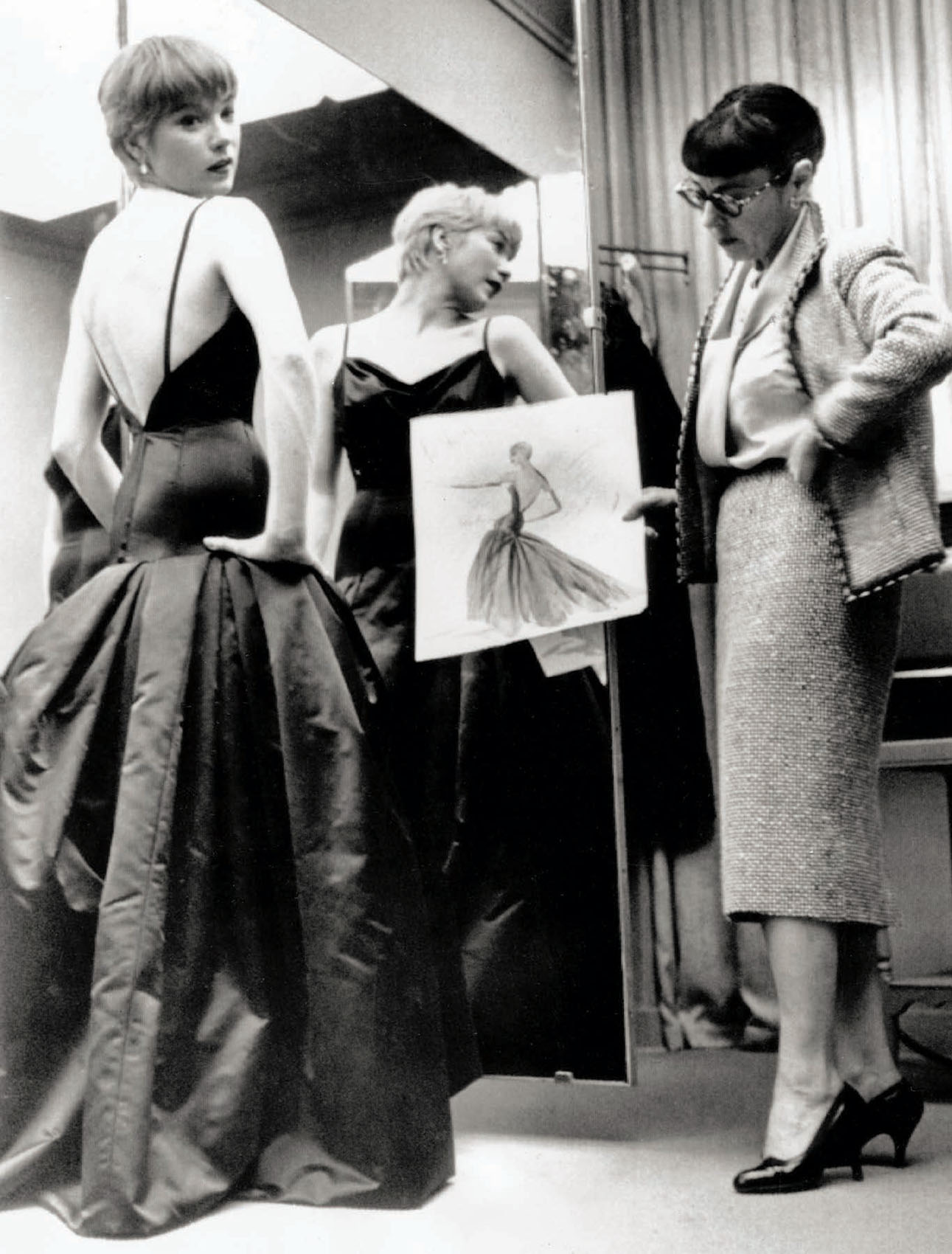

(l-r) Marla English wearing Audrey Hepburn’s gown from Roman Holiday (1953), stands next to Edith Head and actress Gene Tierney. Edith is holding the Oscar she won for designing the film.

A costume sketch for Rosemary Clooney in White Christmas (1954).

After Kelly married Prince Rainier of Monaco in 1956, Hitchcock vainly searched for a replacement. First came Kim Novak in Vertigo (1958). Hitchcock envisioned Novak’s character in a severe gray tailored suit, just stepping out of a San Francisco fog, with her hairstyle twisted in a spiral forming a question mark. Novak felt restricted by the suit, and hated the outfit’s black shoes. Novak was sensitive about the size of her feet and believed dark shoes emphasized them on camera. When Novak protested to Head, the designer suggested she speak to Hitchcock. The director held firm. Novak found that having her choice taken away actually helped her understand the character of Madeleine better, and she appreciated that Hitchcock let her come to that realization herself.

Hitchcock discovered his other attempt to replace Kelly, Tippi Hedren, in a diet soda commercial. Although Hitchcock signed Hedren to a seven-year contract, their relationship deteriorated as Hedren could not tolerate Hitchcock’s obsessive control and advances. They only made two movies together. In the first one, The Birds (1963), Hedren arrives in a fur with out-of-place formality. For the scene where she is attacked by the birds, Head resurrected the eau de nil suit worn by Grace Kelly in Rear Window to give Hitchcock the chaste, cool quality he sought. In Marnie (1964), Hedren played a sexually frigid thief. Hitchcock instructed Head that he wanted no eye-catching colors that would detract from the action and wanted to use warm colors to demonstrate that Marnie was, in fact, a warm person.

Shirley MacLaine and Edith Head during a fitting for Career (1959).

A design for Lucille Ball from the mid-1960s.

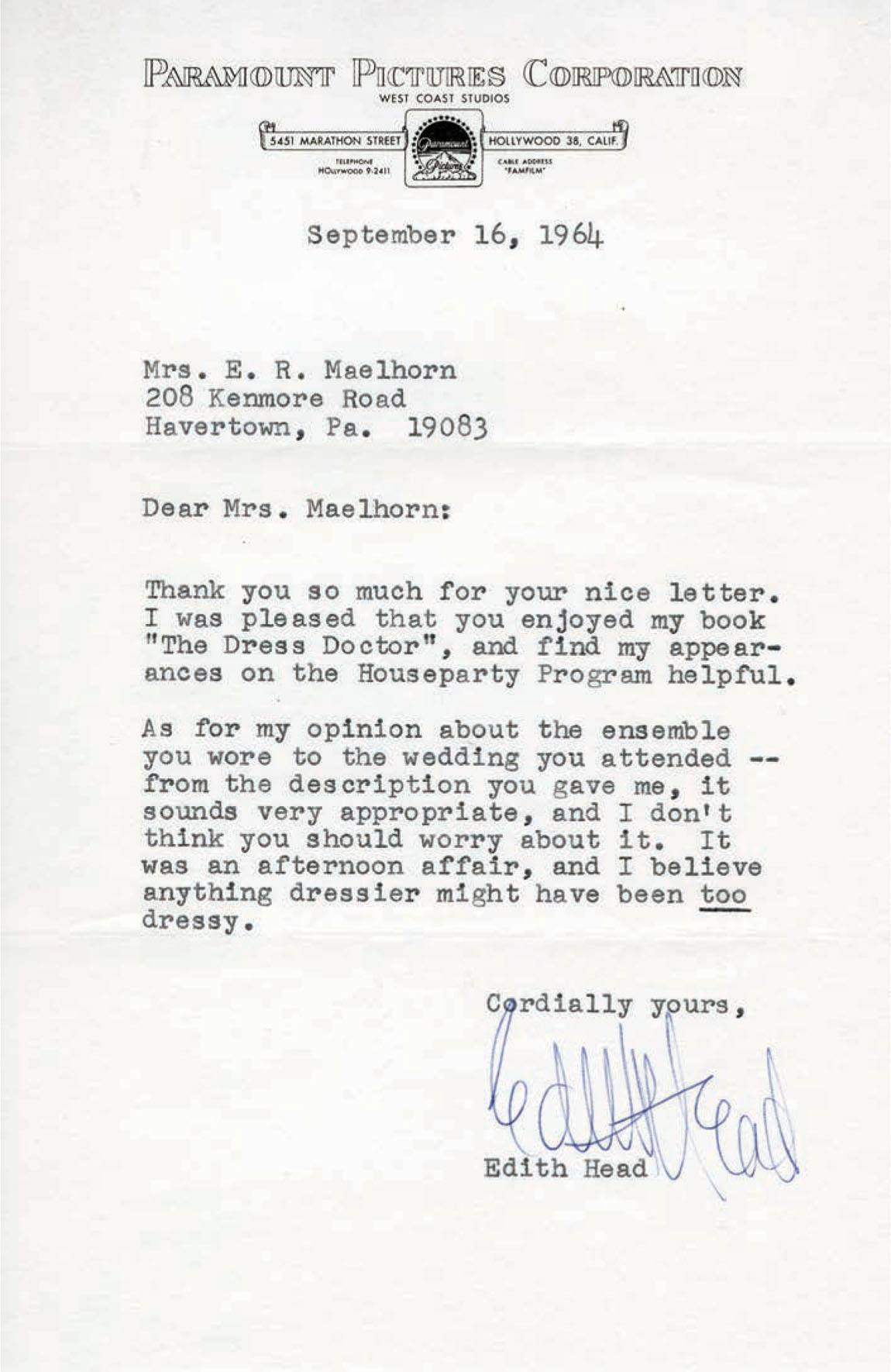

A letter from Edith Head offering advice to a fan.

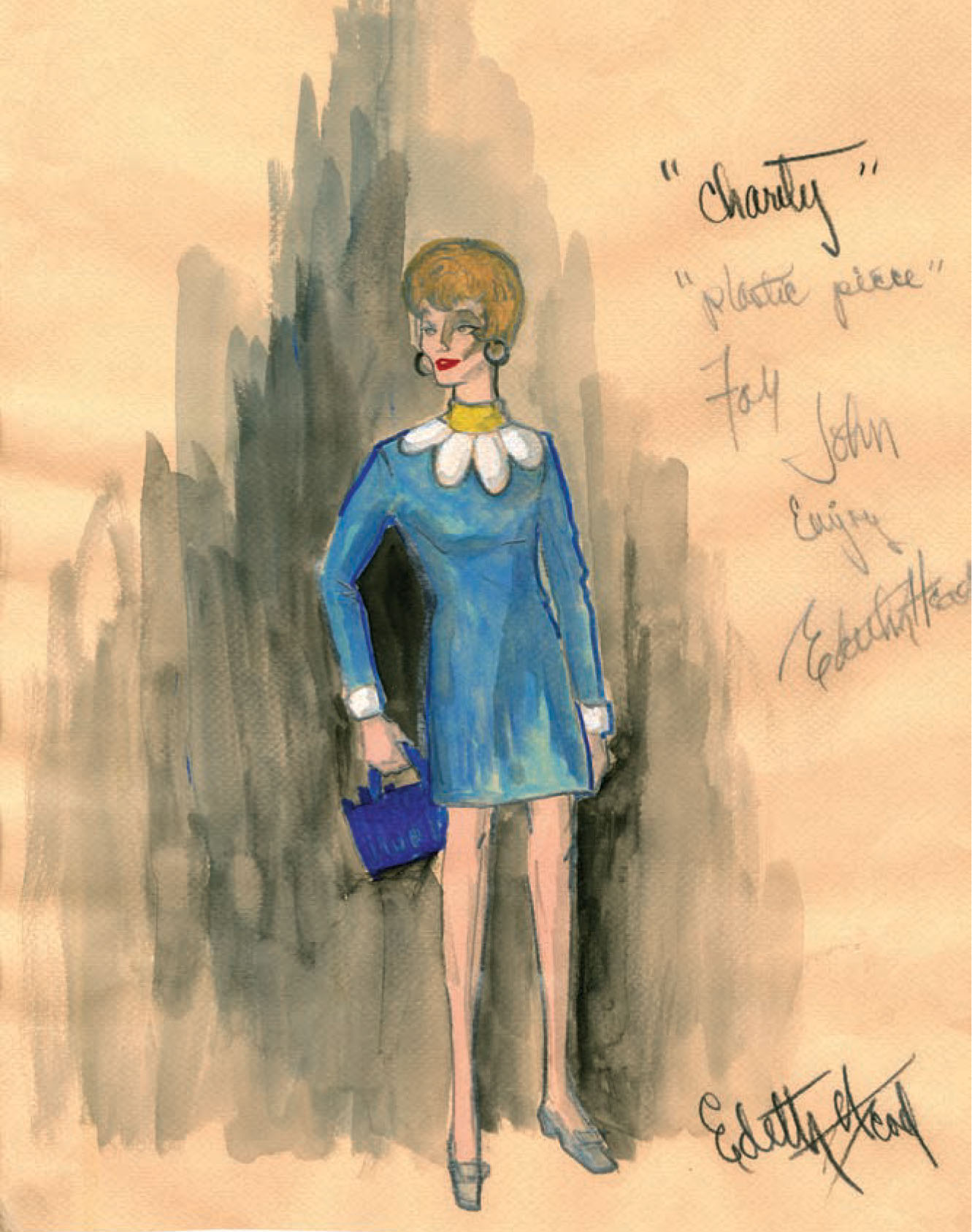

A costume sketch for Shirley MacLaine in Sweet Charity (1969).

Shirley MacLaine poses with the extensive Edith Head wardrobe created for her in What a Way to Go! (1964).

In 1966, when Gulf + Western bought Paramount, Head believed she would be forced out of the studio. She negotiated a contract with Universal, where Hitchcock was working. In the late 1960s, glamour was on the wane, but Universal was still producing films with opportunities for Head’s skills as a fashion designer, including The Oscar (1966) and Hotel (1967).

In total, Head won eight Oscars, the last being for The Sting (1973). Though she did not design the wardrobe, the film carried her design credit. That win, her first in fourteen years, made Head a popular fashion adviser to a new generation. The Sting win boosted sales of her dressmaking patterns, marketed under the Vogue trademark, and brought fans to fashion shows, moderated by Head, featuring her old costumes. At Universal, she was more valuable for publicity purposes than for actually designing.

Late in life, Head suffered from myelofibrosis, an incurable bone marrow disease. On the evening of October 24, 1981, Head ruptured her esophagus during a hospital stay and died in Los Angeles, just four days before her eighty-fourth birthday.