Even prolific designers must consider themselves fortunate if they have created just one costume that becomes iconic during their careers. Jean Louis has the fortune of being remembered for at least three of his designs.

There was the black strapless dress Rita Hayworth wore in Gilda (1946), the sparkling gown Marilyn Monroe wore when she sang her “sweet, wholesome” rendition of “Happy Birthday” to President John F. Kennedy in 1962, and Marlene Dietrich’s beaded nude illusion cabaret touring costumes.

Because of Jean Louis’s long affiliation with Columbia and Dietrich’s refusal to star in a Columbia picture, their collaboration almost never happened. Prior to Dietrich becoming a fixture on the Las Vegas stage, Columbia founder Harry Cohn had asked her to star in Pal Joey (1957). Insulted by her refusal, he swore she would never work for Columbia, an odd threat given her refusal to do just that. Little did Cohn know that he would soon get an opportunity for genuine payback. After Dietrich was offered a substantial contract to perform in Las Vegas, she wanted Jean Louis to make her gowns, as her favorite go-to designer, Travis Banton, had died a few years before. Aware of the tiff between Dietrich and his boss, Jean Louis refused. “I cannot even make a scarf without Harry’s permission,” he told Dietrich. So Dietrich supplicated herself before Cohn. With vengeful glee, the studio head turned the Hollywood legend down.

After Cohn’s treatment of Dietrich purportedly displeased some Vegas casino owners, he reconsidered his position, then gave in, but not without setting petty conditions. Dietrich was never to use the front gate at Columbia. She could not be on the lot during normal business hours. She was limited to the wardrobe department for fittings and then was required to leave by the back gate. Dietrich so admired Jean Louis’s abilities, she bore the humiliation and sneaked into Columbia through the back door for several weekends, standing for hours while Jean Louis fitted the bead-encrusted souffle creations in the deserted wardrobe department.

Born in Paris on October 5, 1907, Jean Louis would come to enjoy a well-earned reputation as a gifted Hollywood designer with the impeccable social polish one expected from a refined French gentleman. His first encounter with Marilyn Monroe certainly required his utmost savoir faire. He met Monroe in her Brentwood home to discuss her wardrobe for The Misfits (1961). He waited with his fitter in her living room for more than an hour. When they were about to leave, Monroe sauntered down the staircase. “Oh, I am sorry I am late,” Monroe said. “But I am always late,” she sighed. She wore a mink coat and high heels. “It’s wonderful to meet you. I am so pleased you are going to design the costumes for The Misfits,” Monroe said.

“With a sparkle in her eye, she dropped the fur to the floor,” Jean Louis later recalled. Monroe was totally nude. “I thought you would like to see what you have to work with.” She giggled. “But keep in mind that I never wear undergarments.” Jean Louis was flabbergasted. “I kept looking at her directly in the eyes,” he said. “Miss Monroe,” he finally said. “I see you wearing hats. A lot of hats. Lots and lots of hats!”

Given his origins—the future designer grew up among the waterways of Paris, where his family worked in boats along the Seine River—a career designing for Hollywood’s biggest stars may have seemed improbable for Jean Louis. But from a young age he had an interest in designing women’s clothes. Born Louis André Berthault, the future designer studied art at L’École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The school had no costume design course at the time, so in between his art classes, he taught himself about costumes and how to illustrate them. After school, he worked selling ties until he eventually found work as an illustrator at a traditional fashion house. Jean Louis was displeased with the old styles being shown and re-shown there. Paris was in the midst of a watershed moment—the Jazz Age—and women were wearing new, less-constricted silhouettes. Wanting to help forge new trends, Jean Louis moved to a more modern house, Agnes-Drecoll, on the Place Vendôme, where he worked as a sketch artist for four years. At that time, Jean Louis found that Parisian designers were less inclined to take a risk on a young person, and he was frustrated at the slow pace at which his career was advancing.

Jean Louis’s design for Marlene Dietrich’s nightclub act.

Rita Hayworth in Gilda (1946).

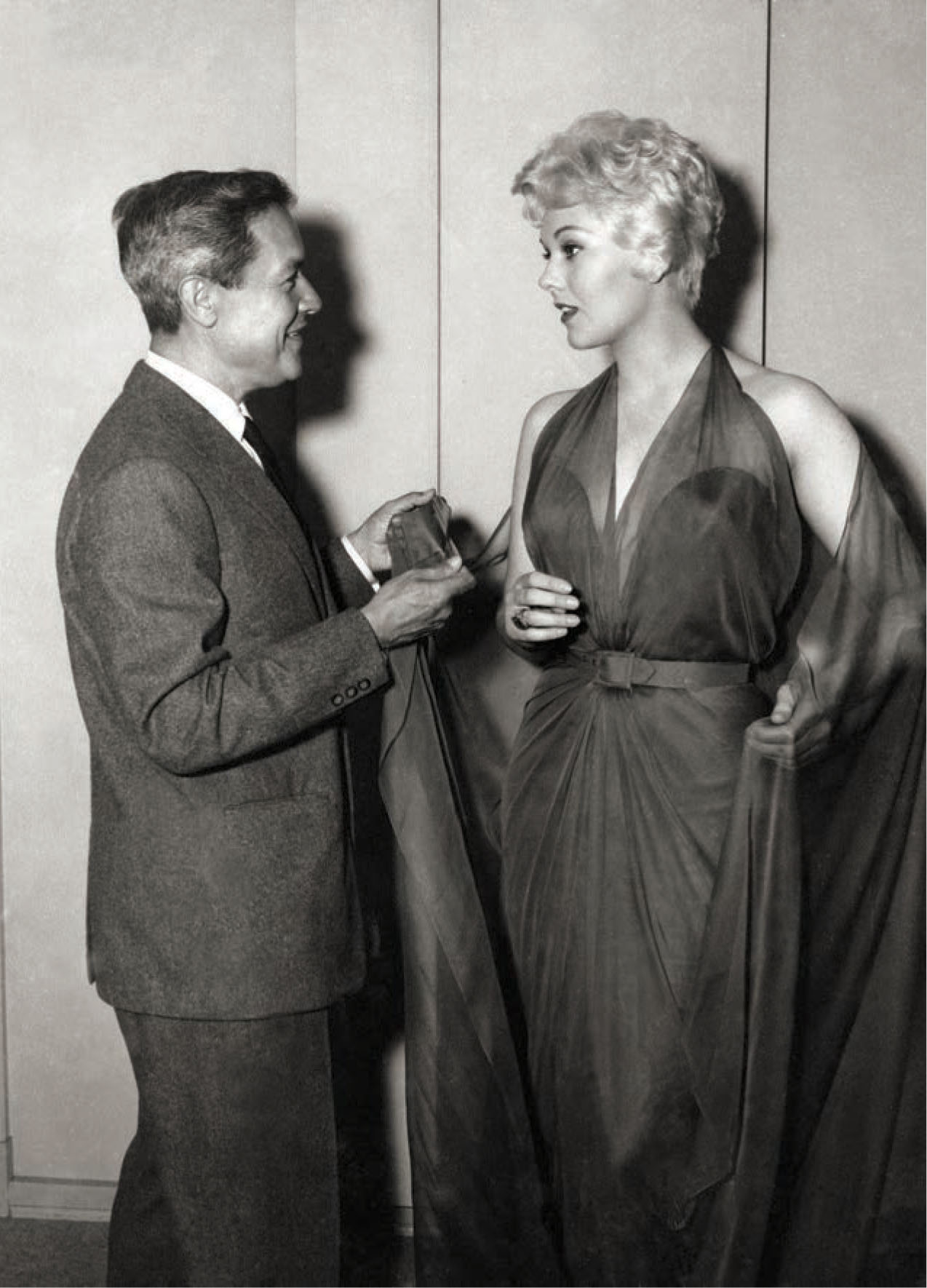

Jean Louis discusses the wardrobe for Over 21 (1945) with actress Irene Dunne.

In 1935, after he broke his arm in a taxi accident, Jean Louis purchased a round-trip ticket to America with the insurance money. He fell in love with New York, even though he spoke little English. The people with whom he was traveling suggested that he should try to stay. He took some sketches to Hattie Carnegie, and told her that he could drape and cut too. She offered him a two-week probationary position. His ship was set to sail in two days, so he cashed in his return ticket and began designing for Carnegie, even though he had no work visa. U.S. Immigration ordered him to return to France.

Three months later, Carnegie navigated the hurdles of U.S. Immigration and brought Jean Louis back to New York. For the next seven years, Jean Louis worked for Carnegie. Designing for film never occurred to Jean Louis until Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures, who was in New York looking for a new designer, paid him a visit at the recommendation of his wife, Joan, a Carnegie patron.

Jean Louis and Cohn came to an agreement. With the exception of Jane Russell, who requested her own designer when on loan to Columbia, Jean Louis personally designed for all Columbia actresses, including Rita Hayworth, Jean Arthur, and Irene Dunne.

Jean Louis (left) and Elizabeth Courtney fit Rita Hayworth for The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

“Rita Hayworth was the most fun and so beautiful,” Jean Louis said when assessing the Columbia stars. “There was nothing common about her. Her nose, her chin, were extraordinary—and those long, long legs.” From the waist down Hayworth was thin—thin legs, no hips, and a small derriere. Jean Louis used certain design tricks, like tight belts, to give her an hour-glass shape. Her hips broadened a bit after her second daughter’s birth, presenting some design challenges for Affair in Trinidad (1952) and Salome (1953). But for Pal Joey (1957), Hayworth’s broader build was appropriate, as she was playing a more mature woman.

Ginger Rogers wearing a Jean Louis gown for It Had to Be You (1947).

Jean Louis’s most successful design for Hayworth was, without a doubt, the gown for her “Put the Blame on Mame” pseudo-striptease in Gilda (1946). “When I did the Gilda dress, it was bolder and sexier than film designs of the time,” Jean Louis said, “but on Rita, it was not vulgar.” The Gilda dress was boned across the bodice, as might be expected. But the fitter also constructed a small strip of plastic across the bust. The plastic was heated with an iron and then bent to fit the exact shape of Hayworth’s body. Because the number was filmed sooner than expected, Hayworth wore the dress without any test run. When Gilda was released, Jean Louis received a telegram from fashion editor Diana Vreeland. All it said was “Superb.”

Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr in From Here to Eternity (1953). Because the couple would be kissing on a beach, Jean Louis had to design a conservative swimsuit for Kerr.

Jean Louis with actress Kim Novak.

When Betty Grable came to Columbia to make Three for the Show (1955), Jean Louis learned the woman with the million-dollar legs preferred pleasing fans over style. “I had designed a strapless dress and had shifted the darts above and below her bustline to give her a ladylike and seductive look,” Jean Louis recalled. “At the first fitting, she eyed herself critically in the mirror and said to me, ‘Remember, I am famous for two things—my bust and my legs.’ With that, she pushed her breasts up until, to my shocked eyes, they seemed to be resting right under her chin. ‘See,’ she said, ‘look how much longer my body looks now.’” Despite Jean Louis explaining to Grable that she had put herself and the dress completely out of balance, Grable was adamant. “What Betty wanted, Betty got,” Jean Louis said. “So we added some thin shoulder straps to support her high bust, slit the skirt almost to the hips to show off her famous legs, and that was that. She might not have had the greatest style sense, but to her, what her public wanted, her public got.”

Joan Crawford in a continuity photograph for Queen Bee (1955).

When Cohn signed Marilyn Pauline Novak to Columbia, he wanted to change her name to Kit Marlowe. Novak balked, and a compromise was reached—Kim Novak. Jean Louis found Novak cooperative, at first. When she first came to the studio, he put her in some of Hayworth’s old clothes, letting the seams out in some and leaving the backs unzipped in others. For her debut at Columbia, Pushover (1954), Jean Louis did not put Novak in a bra. She approved. But when Cohn saw the rushes, he asked Jean Louis why Novak appeared to have no bustline. When Cohn insisted that Novak wear a bra, she cried. She hated wearing bras and argued with the studio chief. Although Novak did win some of her battles with Cohn, this was not one of them. Novak appeared pushed-up in Pushover.

Lana Turner in Imitation of Life (1959).

Novak developed a preference for gluing her dresses to her body, instead of having Jean Louis bone them. At the end of a day of filming, she had to rip the dress off of her body, usually ruining the dress and sometimes tearing her skin. Insecure about her legs, which she regarded as too thick, Novak insisted on wearing beige stockings and beige shoes to make her lower extremities look smaller. Later, she wanted to wear white shoes with all of her outfits because she believed white made her ankles look smaller. Because he understood that Novak’s idiosyncrasies stemmed from her self-doubts, Jean Louis was able to look past them.

Jean Louis was vacationing in Paris when Dietrich contacted him about designing her Las Vegas nightclub costumes. After receiving Cohn’s approval to work for the previously ostracized actress, Jean Louis sent Dietrich five sketches of gowns of various modesties, and she settled on two see-through gowns. The dresses caused a sensation when the stage lights hit the performer because she appeared to have nothing on under them. To create the illusion, Jean Louis used tightly molded souffle material underneath a slightly looser dress on top. The audience appeared to see Dietrich’s body under the dress, but they were actually seeing the souffle.

The mid-1950s brought significant changes in Jean Louis’s personal and professional lives. The handsome Frenchman was the groom in two successive weddings back-to-back in 1954 and 1955. On August 7, 1954, he married Marcelle Martha Martin, a fellow French immigrant twelve years his senior. They had met eighteen years before in New York, when she worked for Hattie Carnegie. They reconnected in California when Marcelle visited her sister in Los Angeles. Jean Louis and Marcelle married months later in Santa Barbara. Their happiness was short lived; Marcelle died within a year of cancer. Four months later, on November 26, 1955, Jean Louis married Maggy Fisher, an editor at Radio and TV Daily. She had also known Jean Louis for about twenty years, having met when he was studying art in New York and she was a model. Their marriage lasted nearly thirty-five years, ending with Maggy’s death the day after her seventy-seventh birthday on September 27, 1989.

Marilyn Monroe in the unfinished Something’s Got to Give (1962).

A costume sketch for Doris Day in Send Me No Flowers (1964).

A couple of years after Jean Louis wed Maggy, his boss at Columbia, Harry Cohn, died on February 27, 1958. Despite plenty of bad press over the years about Cohn’s alleged difficult personality, Jean Louis never had a bad experience with him. When the new owner took over Columbia after Cohn’s death, Jean Louis was told the studio would renew his contract, but at a reduced salary. Having been at Columbia for seventeen years, Jean Louis felt as if he was being told to start over. He chose to leave Columbia and began freelancing.

In 1960, Jean Louis signed to do a spring collection each year for New York fashion house Ben Reig. A clause in the contract promised Jean Louis time off between collections to make movies. After two months at Ben Reig, Jean Louis was asked to do The Misfits (1961). Even though Jean Louis had completed the first season’s collection, Reig objected to Jean Louis leaving for California, claiming that the designer would be deserting his workroom staff. Reig insisted Jean Louis create a reserve line. Although not contractually obligated to do so, Jean Louis acquiesced so that he would be able to work on the film. Tensions between Jean Louis and Reig over the former’s filmmaking eventually proved to be a deal breaker.

Following The Misfits, Monroe chose Jean Louis to design her wardrobe for her next film, Something’s Got to Give (1962). Tensions between the actress and 20th Century-Fox were high; Monroe’s frequent tardiness and absenteeism had studio heads seriously considering her termination. When she was invited to sing “Happy Birthday” to John F. Kennedy at Madison Square Garden, Monroe feigned illness and played hooky from the set. She secretly ordered a form-fitting gown from Jean Louis. Dubbed the “beads and skin” dress, the gown was made of nude marquisette fabric encrusted with 2,500 rhinestones. Monroe and the dress miraculously arrived in New York without studio heads catching wind of the clandestine trip. But after 20th Century-Fox saw clips of its AWOL star shamelessly vamping before the president at the Democratic fundraiser, Monroe was fired. Three months later, she was dead.

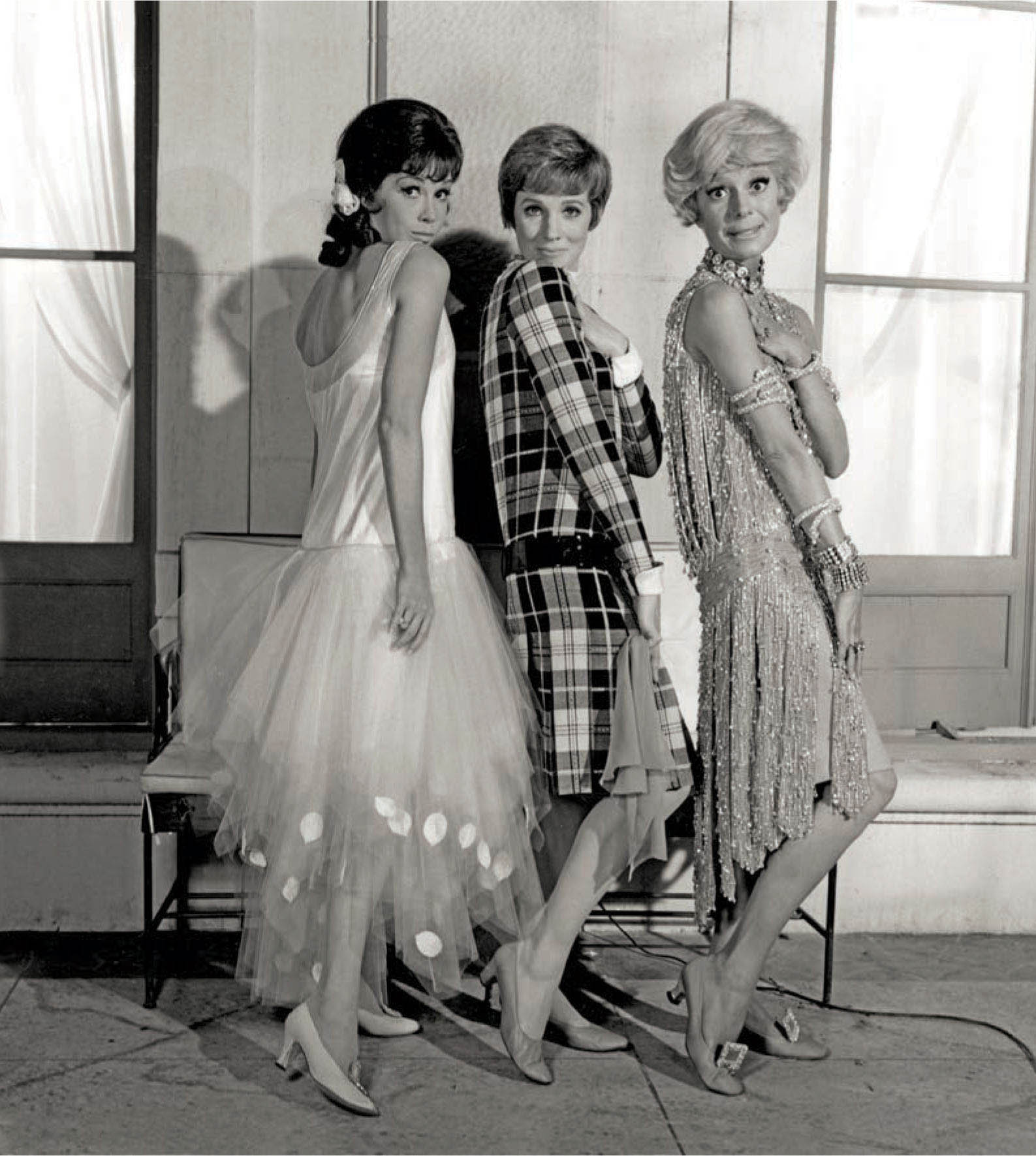

Mary Tyler Moore, Julie Andrews, and Carol Channing in Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967).

Jean Louis never believed that Monroe intended to kill herself on that fateful August night in 1962. Just a few days before, she had called the designer with a rush order for a dress. Because she did not wish to disturb him at home, she set up an appointment to come to his office the following Monday. “I was at church that Sunday when the priest told me of her death that weekend,” Jean Louis said.

At the time he began designing for Monroe, Jean Louis was also pleased to begin his association with producer Ross Hunter at Universal, designing for Lana Turner in Portrait in Black (1960). Hunter was the only producer in the 1960s still interested in making glamorous films. He was not always easy to please though, insisting that Jean Louis stick to pastels, which Hunter believed best flattered his stars.

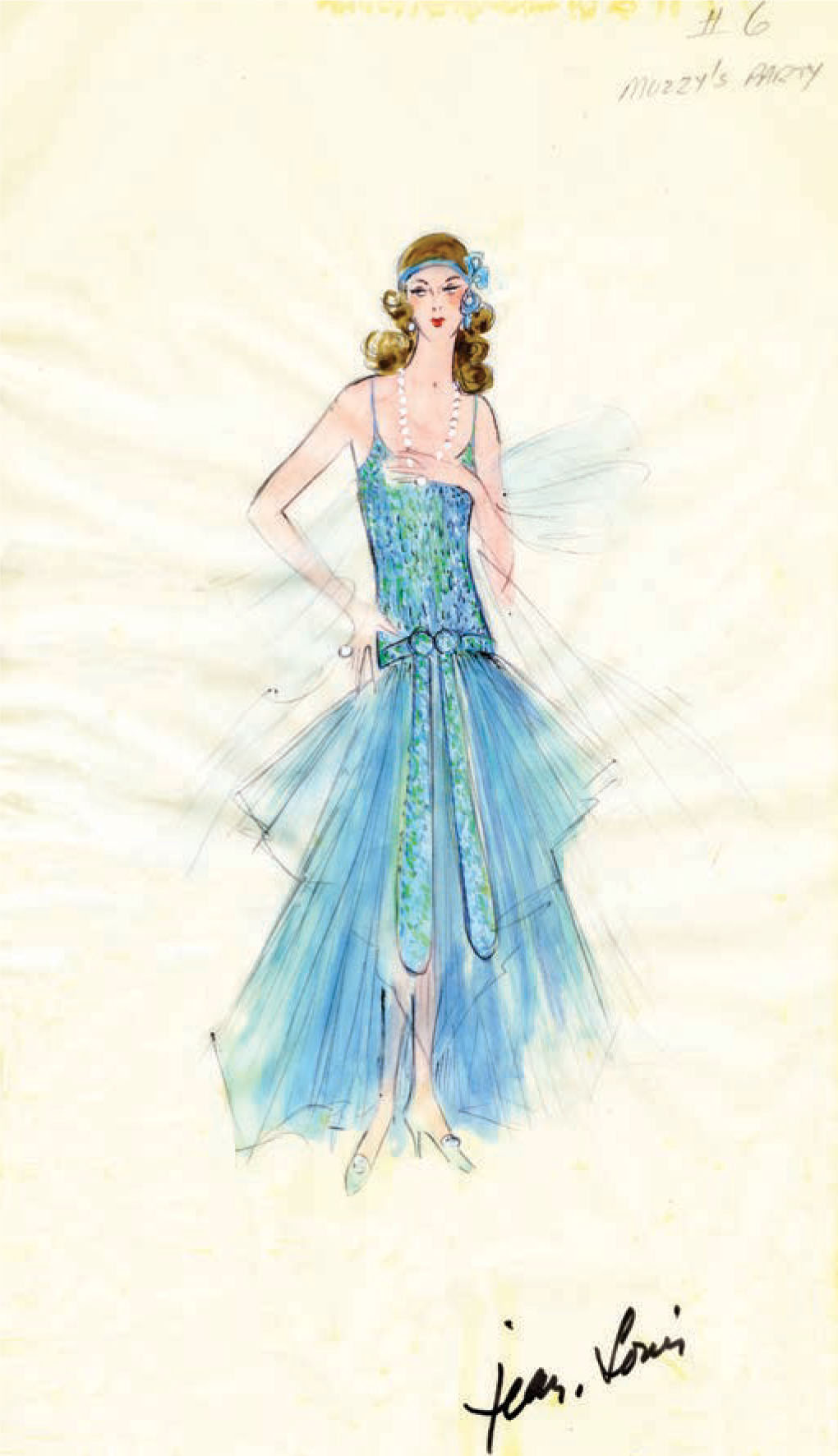

A costume sketch for Mary Tyler Moore in Thoroughly Modern Millie.

When his collaboration with Ben Reig ended, Jean Louis opened his own ready-to-wear business. Surprisingly, his venture did not flourish as quickly as his design talents might have predicted. He was not a great businessman. The business did under $1 million annually. His lines were sold through department stores like Saks Fifth Avenue and I. Magnin & Co. His private client list for custom clothing included Nancy Reagan, Edith Goetz, and Lee Annenberg.

During the 1950s, Jean Louis and his wife, Maggy, became friends with actress Loretta Young. Their friendship was so well known that insiders referred to the trio as “The Three Musketeers.” Jean Louis had even contributed designs to The Loretta Young Show, which the actress wore as she famoulsy swept through the door at the opening of each episode. After Maggy died in 1989, Young looked after Jean Louis, who was becoming frail. The two surprised their fans when they wed on August 10, 1993. Jean Louis was just shy of his eighty-sixth birthday. Young was eighty.

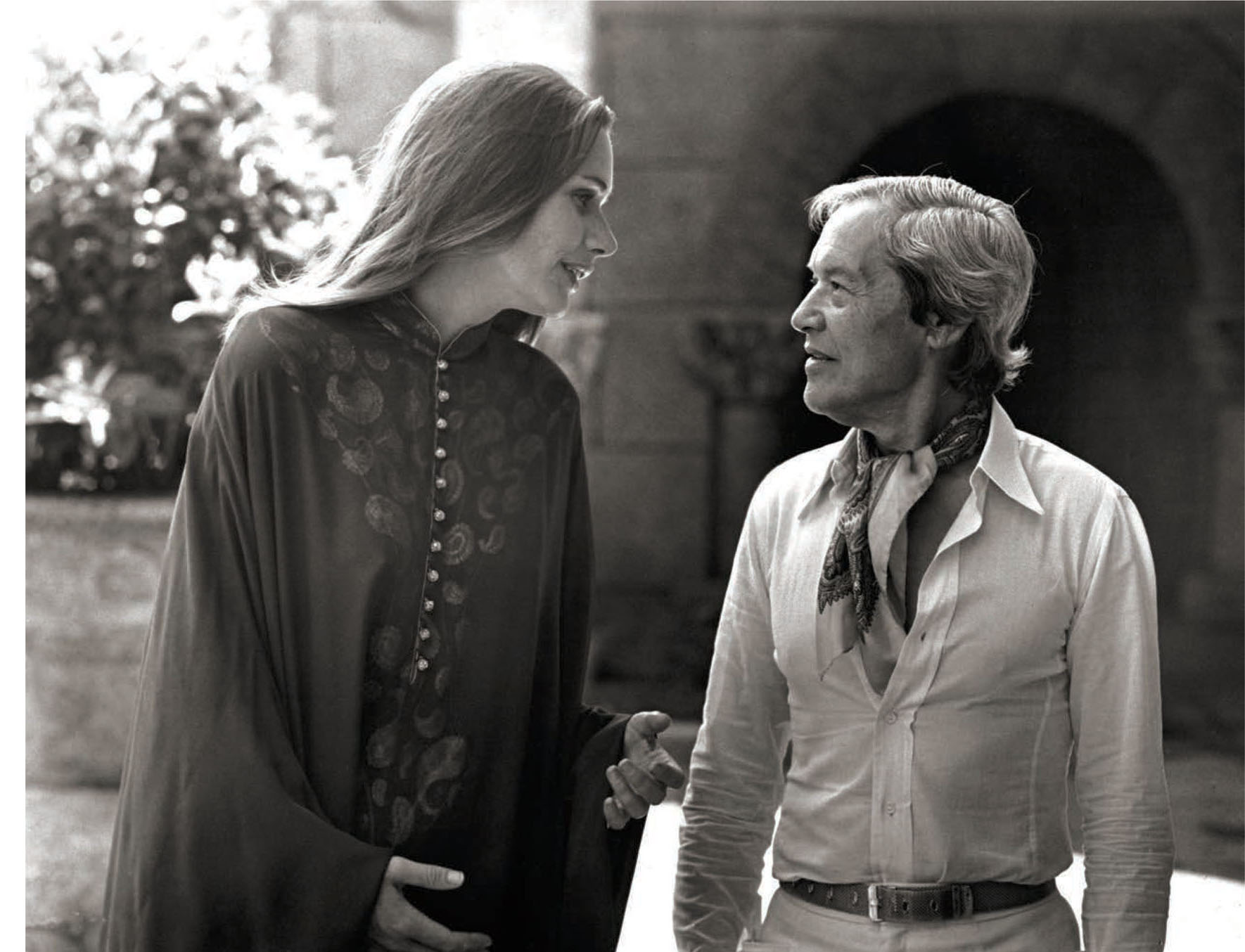

Actress Sally Kellerman and Jean Louis on the set of Lost Horizon (1973).

Though Young did take care of Jean Louis at the couple’s home in Palm Springs until his death, insiders believed love was not the primary impetus for their marriage. The year of the wedding, 1993, Young’s adopted daughter, Judy Lewis, had written a book revealing that she was actually the biological daughter of Young, a product of her mother’s clandestine affair with actor Clark Gable. Being a devoutly religious woman, Young strongly believed that getting married at the time of the book’s release would somehow help her image. Whether Jean Louis was cognizant of Young’s motives is uncertain. Always the gentleman, he undoubtedly had no hesitation helping his friend. Jean Louis died at eighty-nine on April 20, 1997. Young died three years later, on August 12, 2000.