WILLIAM TRAVILLAWILLIAM TRAVILLA

Sometimes a costume becomes so unforgettably associated with an actress that the mere mention of her name brings the iconic outfit instantly to mind.

Can anyone say Marilyn Monroe’s name without the image of her white cocktail dress fluttering over a subway grate in The Seven Year Itch (1955) inescapably coming to mind? The creator of that billowing dress, William Travilla, designed for Monroe in eight movies, but never so memorably as in that famous scene. Years later, Hollywood would learn that the designer was in love with Monroe at the time.

Their collaborations began early in each of their careers. The two met at Fox in 1950. At thirty, Travilla was a relatively young designer, though he had already won an Oscar for Errol Flynn’s costumes in Adventures of Don Juan (1948). Monroe was a twenty-four-year-old starlet. She had asked to use the fitting area adjacent to Travilla’s office to try on a bathing suit for a photo shoot. After putting the suit on, she asked Travilla’s opinion. Before he could say a word, the shoulder strap broke, revealing one of Monroe’s breasts. Whatever thoughts Travilla may have had about the bathing suit were instantly forgotten. As time went on, Monroe continued to seek Travilla’s opinions about her clothes for photo shoots. When he did not like them, he would pull better choices from stock for her. As her popularity grew, and magazines and newspapers bombarded the studio for more and more photographs, Monroe requested that Travilla style her for all of her shoots.

Not until 1952 did Travilla actually design original clothes for Monroe. In Monkey Business (1952), he designed the wardrobe for both her and Ginger Rogers. Surprisingly, Monroe was unhappy with one of Travilla’s designs, though it was not the designer’s fault. Director Howard Hawks insisted that Monroe wear a full skirt for the roller skating scene with Cary Grant. Although Monroe wanted to don the hip-hugging tight skirts she always preferred, she lacked the clout to override Hawks. Travilla designed a jersey wool dress with a pleated skirt for Monroe. When he arrived on the set for shooting, he noticed the dress did not appear how he had designed it. The change confounded him—until—Monroe turned around. To get the skirt tighter around her hips, Monroe had surreptitiously tucked the pleats into the crack of her buttocks.

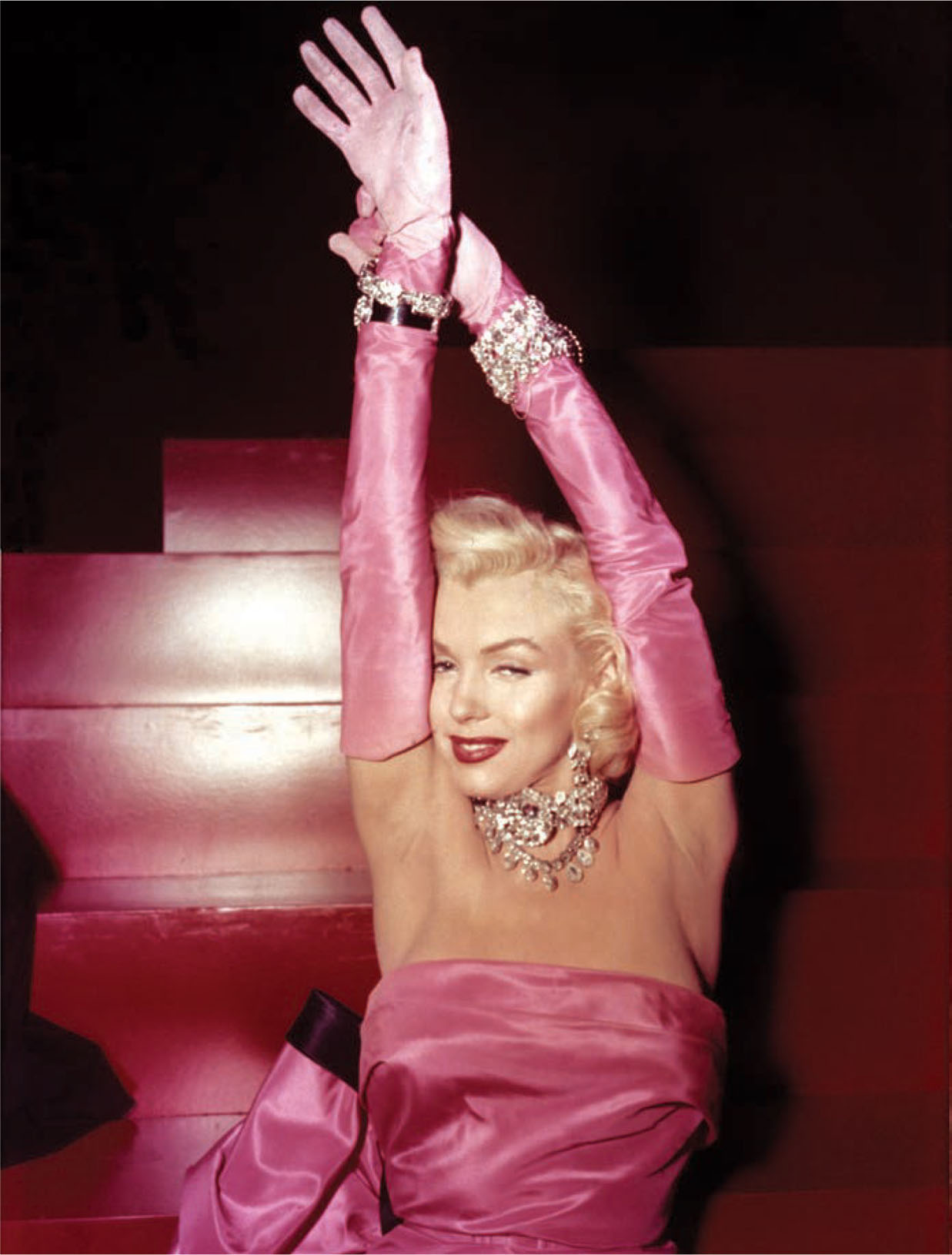

A year later, Travilla designed what would be the second-most famous gown for Monroe, after the Seven Year Itch white cocktail dress. The candy pink silk peau d’ange gown with the giant bow on the back for the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) was actually Travilla’s second design for that sequence. During production, a scandal had erupted when the press revealed that Monroe had once posed nude for a pin-up calendar, causing studio chief Darryl Zanuck to scrutinize Monroe’s wardrobe carefully. For the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number, Travilla had originally designed a costume straight out of burlesque. The outfit, a body stocking covered in black fishnet with essentially a rhinestone-encrusted G-string and bra, was now deemed too revealing. His solution was a pink gown, full-length gloves, and multiple diamond bracelets. The effect of covering Monroe proved even more alluring than Travilla’s original conception, and the gown became one of the designer’s most identifiable creations. Madonna copied it for her “Material Girl” video in 1985.

Travilla was born William Jack Travilla on March 22, 1920, to John “Jack” and Bessie Louise Snyder Travilla, in Avalon, on Santa Catalina Island, just off the coast of Los Angeles. Bessie died when William was just two years old. Much of the Travilla family was involved in show business. William’s aunt, Sybil Travilla, acted under the names Sybil Seely and Sibye Trevilla, often with Buster Keaton in his early two-reel comedies. William’s father and uncles formed a vaudeville group, the Three Travillas. They performed stunt diving on Catalina Island. Jack’s career came to a sudden and terrifying end when he suffered a severe head injury during a performance. He changed careers, operating a tire store in Los Angeles the rest of his life. When William was a grade schooler, his father married Ruth Calderwood, who gave birth to William’s half sister, Joan Travilla, on April 11, 1929.

Tom Ewell and Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch (1955).

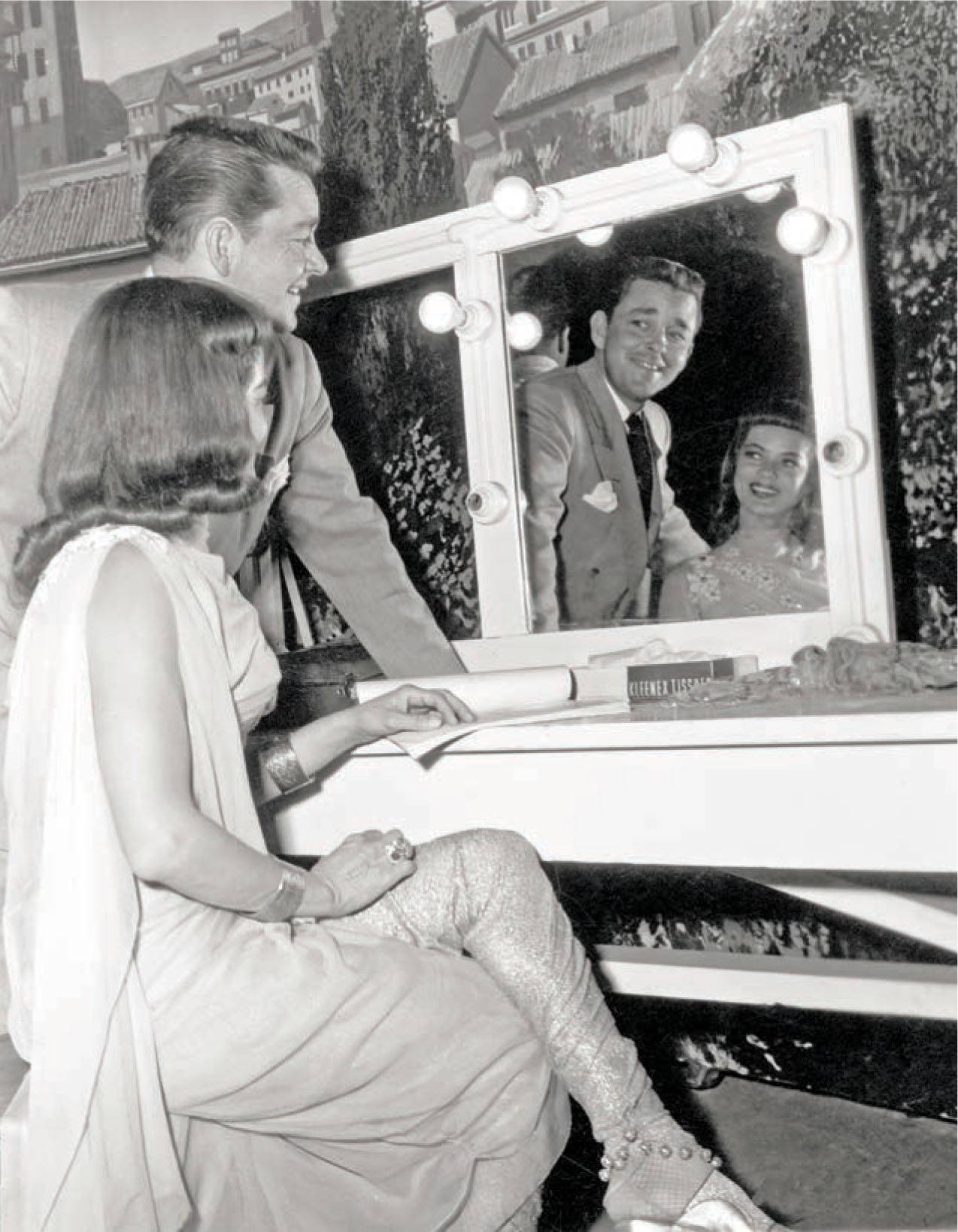

William Travilla fits Ann Sheridan for Silver River (1948).

Travilla’s stepmother recognized his interest in art and enrolled him at the Chouinard School of Art at age eight. The instructors found him so capable, they quickly advanced him into adult classes. When Travilla’s grandmother learned that Chouinard’s curriculum included sketching live nude models, the horrified matriarch purchased her grandson a violin, hoping that music could give the boy’s creativity a wholesome outlet. Already impressed with her stepson’s artistic aptitude, Ruth smashed the instrument over her knee, and Travilla continued his art studies without further interference from his grandmother. At fourteen, Travilla enrolled in the professional arts and design program at Woodbury College (now Woodbury University) in Burbank, graduating in 1941. While at Woodbury, William frequented burlesque clubs after class and sold sketches of costume ideas to some of the performers.

In 1941, when William was twenty years old, his maternal grandfather died, leaving his namesake a small inheritance. With that money, Travilla, along with his grandmother, and aunts, traveled to the South Seas, where he painted portraits of the natives of Tahiti. Upon his return to Los Angeles, he briefly sketched for Western Costume and then moved to Jack’s Costume, a company known for providing wardrobe to ice shows and circus performers. There Travilla met ice skater Sonja Henie, who was dissatisfied with her current designer. Travilla soon showed that he could put more than flash in his clients’ costumes, but actually make the performers more beautiful as well.

While still employed at Jack’s, Travilla worked on movie assignments for Columbia and United Artists in 1942 and 1943. In 1944, he met exotic actress Dona Drake when she came to Jack’s to have some costumes made. The couple married ten days after meeting. Six years Travilla’s senior, Drake had been performing in show business since her early teens. Born Eunice Westmoreland, Drake first affected an exotic Latin heritage when she appeared as Rita Rio in an all-girl orchestra and singing group in the 1930s. Drake successfully perpetuated her image as a Hispanic actress when she was under contract to Paramount, appearing in Aloma of the South Seas (1941) and The Road to Morocco (1942). In truth, Drake was African American and white mixed, and her family worked menial restaurant jobs. She hid her secret not only from the world, but also from her husband. Had she done otherwise, her 1944 marriage to Travilla would have been a legal impossibility. The California Supreme Court did not declare the state’s anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional until 1948.

(l-r) Charles Ruggles, June Haver, Gordon MacRae, and Rosemary DeCamp in Look for the Silver Lining (1949). Costume design by William Travilla and Marjorie Best.

Hoping to garner more designing assignments, Travilla started a design business called The Costumer. He intended to collaborate with studio designers, but in the end, he tended to get assignments only when a designer was in trouble on a project. To earn extra money, Travilla recalled his South Seas trip by painting a series of semi-nude Tahitian women on black velvet. He sold them at Don the Beachcomber restaurant. Actress Ann Sheridan purchased several to decorate a boyfriend’s apartment. Travilla met her one evening at the restaurant. At her request, Warner Bros. hired Travilla for ten weeks at $1,000 a week to design for Sheridan in Nora Prentiss (1947). The film turned out to be a great showcase for Travilla’s designs, and the clothes earned favorable notices. His second film with Sheridan, Silver River (1948), was also well received. Travilla’s success could not have come at a better time. Drake gave birth to the couple’s daughter, Nia, on August 16, 1951. Because of her challenges with epilepsy and emotional problems, Drake preferred to focus on motherhood. She was relieved to have Travilla’s income for the family’s support.

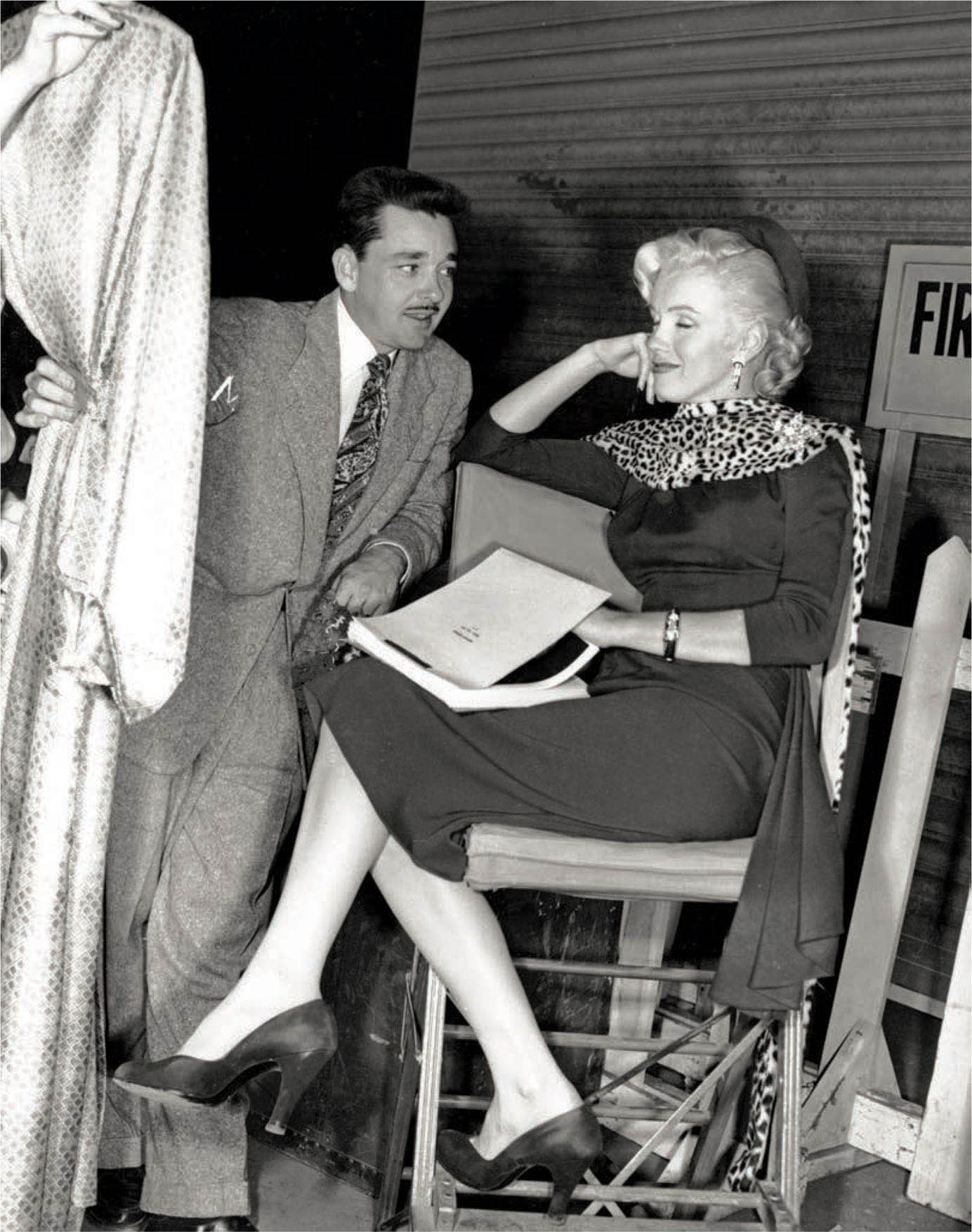

William Travilla and Marilyn Monroe on the set of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953).

After Travilla’s success with Sheridan, Errol Flynn asked him to design his costumes for Adventures of Don Juan (1948). Marjorie Best had been brought on to design the costumes originally, but Flynn considered her designs too “true” to the period, which meant not manly enough for Flynn’s tastes. Travilla replaced the ruffles with a slim-lined doublet and tights, still keeping with Flynn’s swashbuckler image. Travilla found Flynn surprisingly obsessive about details, like the placement of seams and the fitting of collars. In the end, Flynn was pleased with Travilla’s designs. At the Oscars the following spring, Travilla, Best, and Leah Rhodes, who designed for Flynn’s costars, took home the Oscar for color costume design.

A wardrobe test for Marilyn Monroe for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

The discarded outfit for the “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” number, deemed too suggestive after Monroe’s nude modeling came to light.

Marilyn wore a Travilla gown for a 1954 appearance on The Jack Benny Show.

The replacement dress for the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

Another Hollywood player took note of Travilla’s work for Sheridan. Charles Le Maire, costume head at 20th Century-Fox, found one of Travilla’s creations for Sheridan the most beautiful suit he had ever seen. He offered Travilla a position at Fox. Right from the start, Travilla’s designs pleased his new boss, although Le Maire found Travilla’s fabric choices odd. They seemed too stiff for his designs. Le Maire taught Travilla to use chiffon instead of stiff taffeta or heavy satin, a lesson Travilla did not forget when he produced his ready-to-wear collection years later.

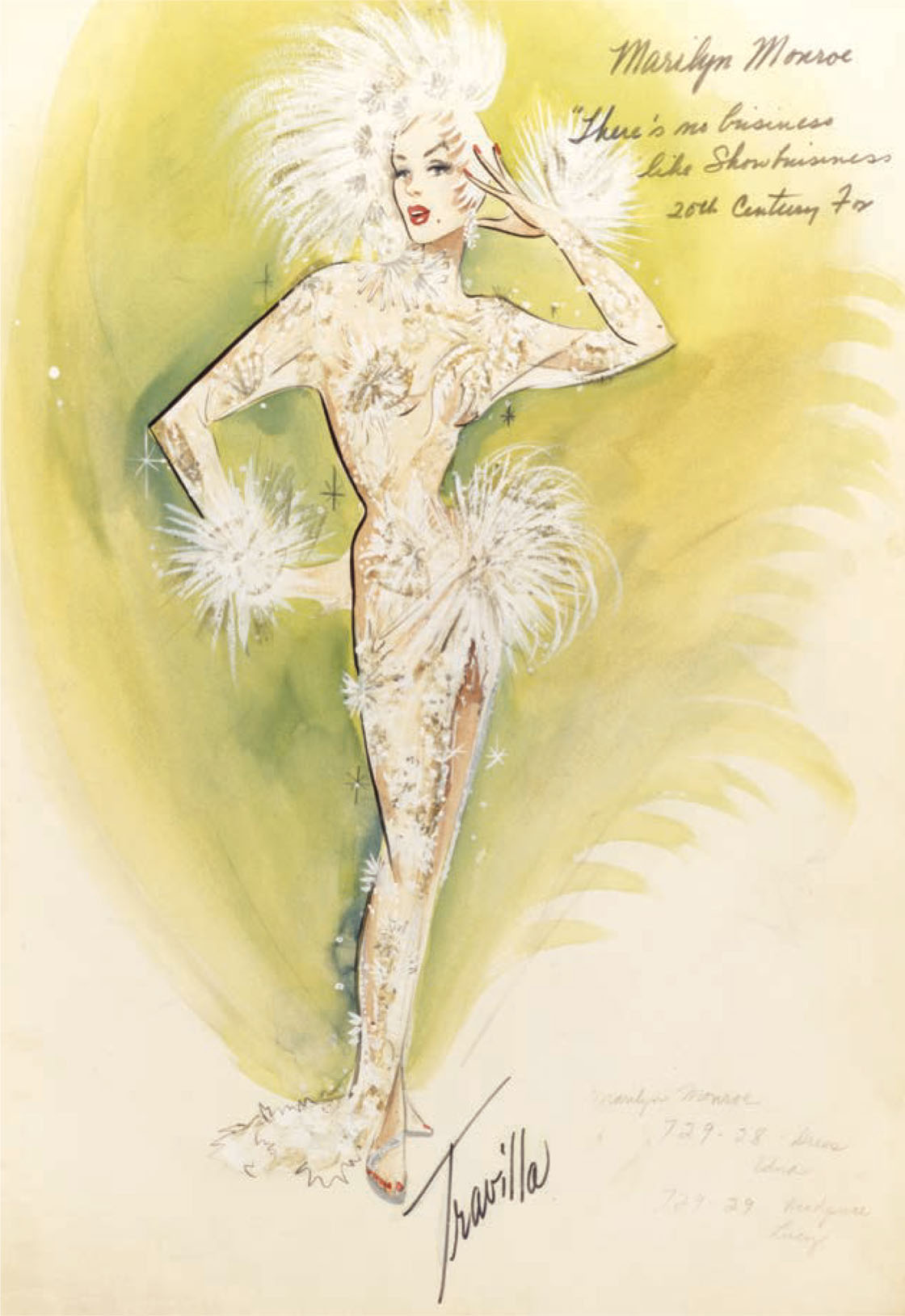

For There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954), in the finale number, Monroe had difficulty keeping in step with the rest of the cast as they descended a staircase. After several failed takes, Monroe accidentally on purpose spilled coffee on the dress during a break. “This got back to Zanuck,” said Hollywood historian David Chierichetti. The studio head’s solution was simple. “I want you to make ten copies of that dress tonight,” he told Travilla, “and if she plays this game with us tomorrow, we’ll just keep putting them on her.” When Travilla told Monroe about Zanuck’s plan, the star burst into tears. “Billy, every day a little piece of me breaks off and dies,” she said, “and soon there won’t be enough left, and when that happens, will you hide me?” This was in 1954.

A William Travilla costume sketch for Marilyn Monroe in There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954).

Le Maire and the studio brass began to realize just how much the studio’s most important star was relying on Travilla for emotional support. Monroe’s boundless need for attention and reassurance consumed much of the designer’s time. “Travilla would have to stay at the studio with Marilyn until late at night,” Chierichetti said. “He had to be wherever Marilyn needed him, and he was relieved of all of his other duties on other pictures when Marilyn was shooting something. As talented as Travilla was as a designer, he was more important to the studio as Marilyn Monroe’s confidante that kept her going.”

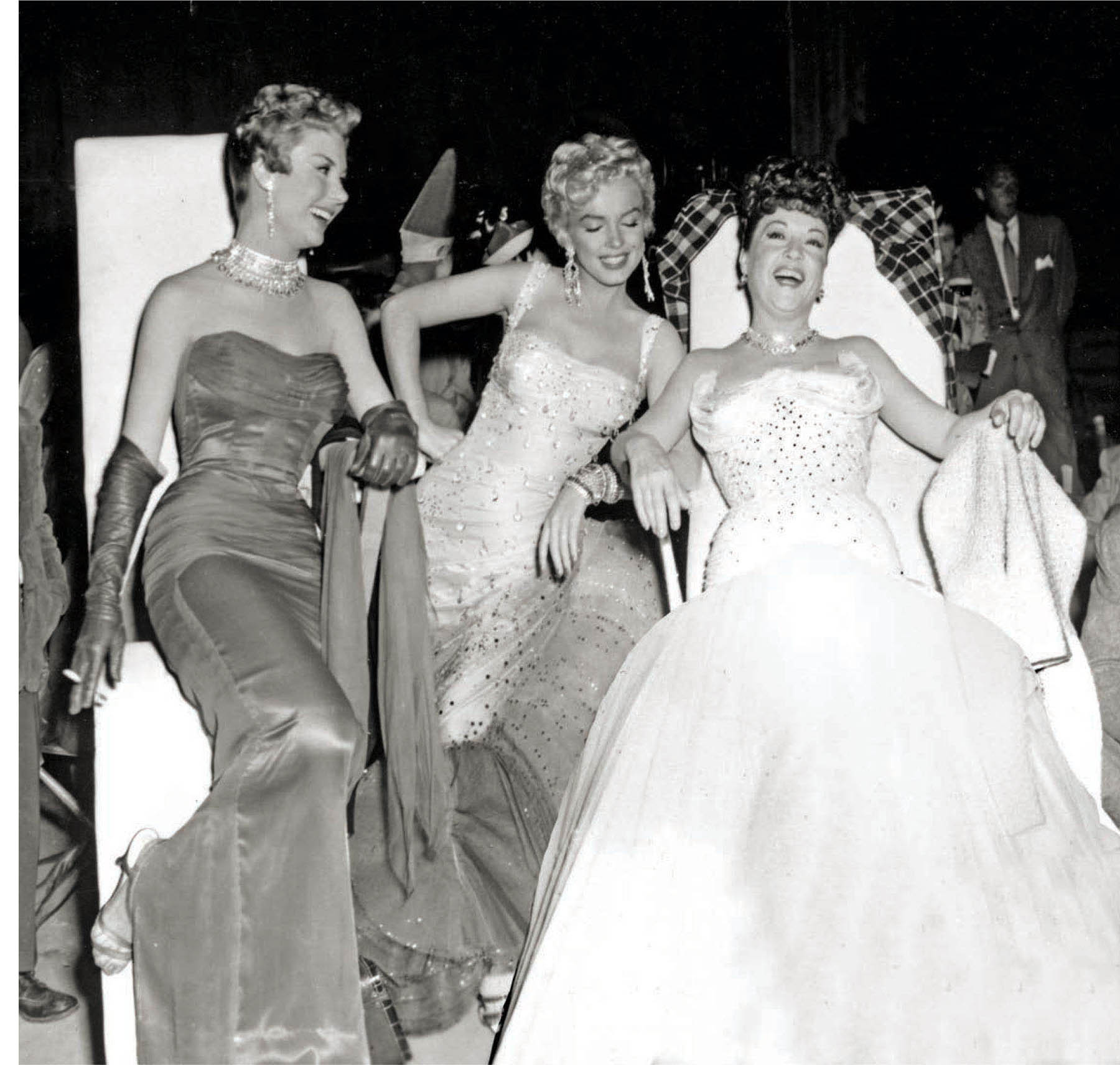

Mitzi Gaynor, Marilyn Monroe, and Ethel Merman on the set of There’s No Business Like Show Business.

The two even went out on the town socially. On one occasion, Travilla took Monroe to the Tiffany Club to hear Billie Holiday sing. As Travilla passed the manager’s office, he noticed Monroe’s nude pin-up calendar on the wall. Because Monroe had never seen the calendar, the pair went back to get a glimpse. When they discovered the office door now closed, Monroe knocked. She told the man answering the door that she wanted to see the calendar. Through the door crack, Monroe and Travilla could see Holiday. The blues chanteuse took the calendar from the wall, crumbled it, and threw it out the door at Monroe, yelling, “Here you are, bitch!” Disgusted, Travilla complained to the manager, and the couple left. The reports of the incident in the rags the next day totally got the story wrong. The owner of the Tiffany Club erroneously told a reporter that Travilla had been offended by Monroe’s nude calendar and had caused a fight at the club.

William Travilla and his wife, Dona Drake.

Drake was furious when she read that her husband had been out with Monroe. While the studio supported Travilla’s relationship with the troubled actress, his wife certainly did not. Drake was jealous. She had suspected her husband of having affairs before. This time, Travilla’s relationship did blossom into an affair with Monroe, though she was dating Joe DiMaggio at the time. The affair did not last. Not only was Travilla married, but he could not usurp DiMaggio in Monroe’s affections. Monroe married DiMaggio in January of 1954, and shot The Seven Year Itch in the fall.

For the famous subway grate scene, Travilla selected white crepe for Monroe’s dress to give her a clean contrast from the gritty streets of New York City. The halter bodice and sunburst pleated skirt completed the fresh feel he sought. The studio heads seemed to intuitively know that the scene was going to be memorable. The Fox publicity department invited dozens of freelance photographers to capture the scene as it was being filmed. Newspapers and magazines worldwide published thousands of pictures of Monroe’s dress blowing up in the train gust, not only generating heightened box-office interest, but helping to secure the scene’s legacy as one of the most iconic images in the history of film. In 2011, Debbie Reynolds sold the dress for $4.6 million dollars when she liquidated her collection of Hollywood memorabilia.

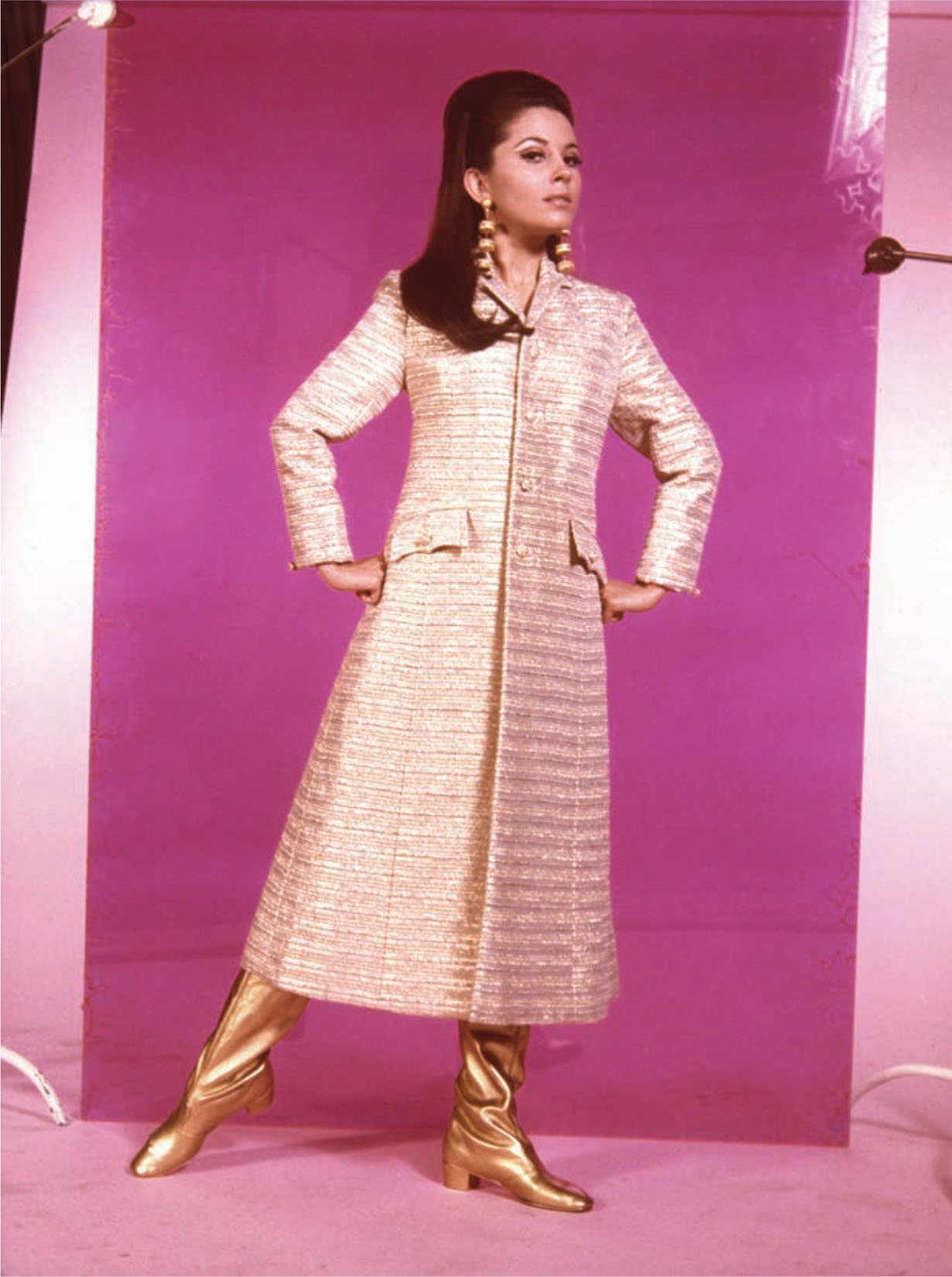

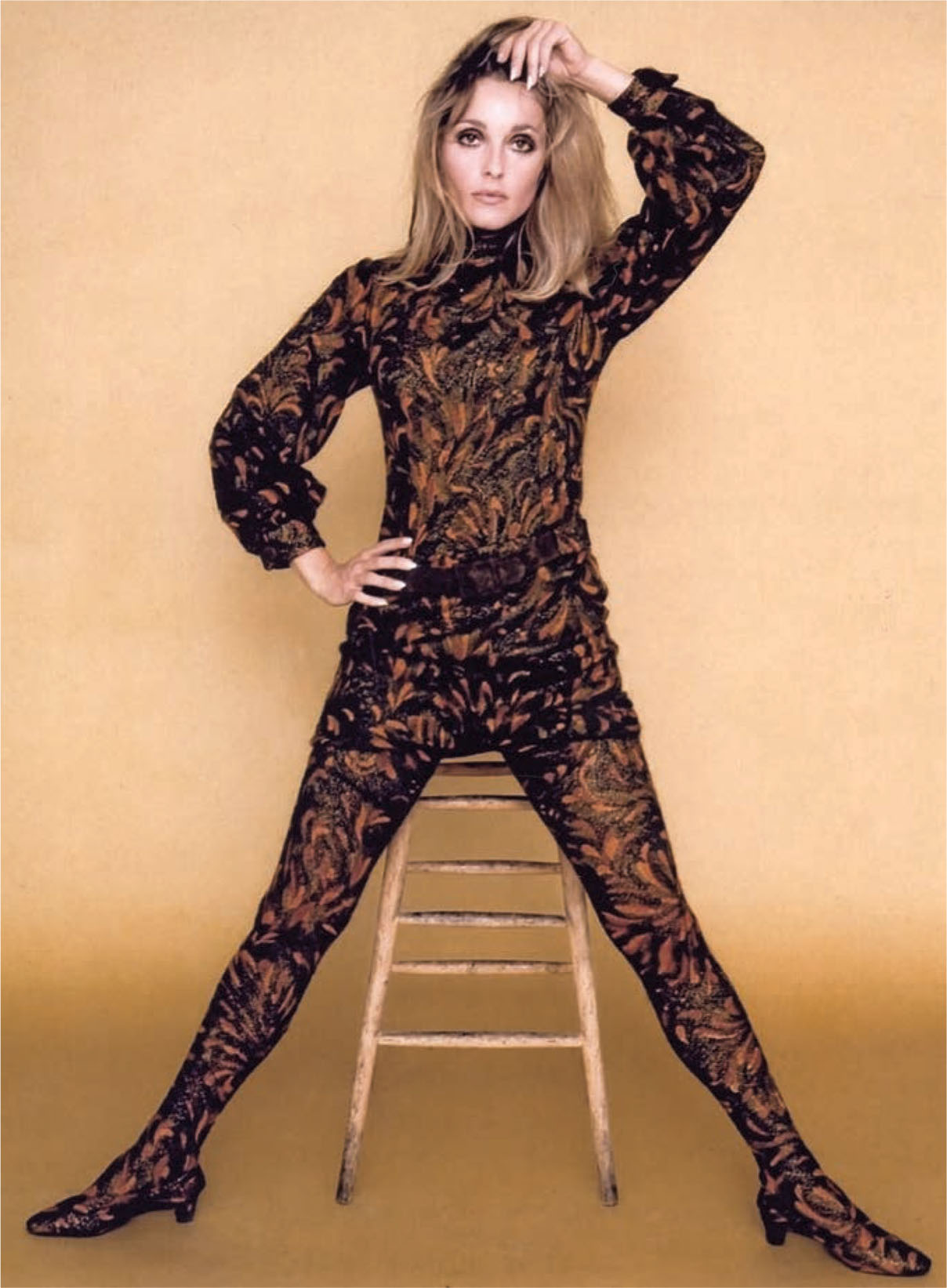

Sharon Tate in Valley of the Dolls (1967).

As television began to overtake movies in popularity toward the end of the 1950s, Travilla became concerned as studios laid off staff and curtailed production. With an eye to his own financial survival, Travilla obtained Le Maire’s permission to open his own retail business with his assistant, Bill Sarris, while the two continued at Fox. Together they started Travilla Inc., with the intention of selling their collections through upscale department stores.

Although Travilla promised Le Maire to be available whenever needed at the studio, the demands of his retail business prevented him from doing so. Le Maire and Travilla both agreed it was time for Travilla to leave Fox. Also around this time, Travilla separated from Drake, though the couple remained married until Drake’s death decades later. Their daughter, Nia, came to live with her father in the mid-1960s, when Drake’s emotional problems became severe.

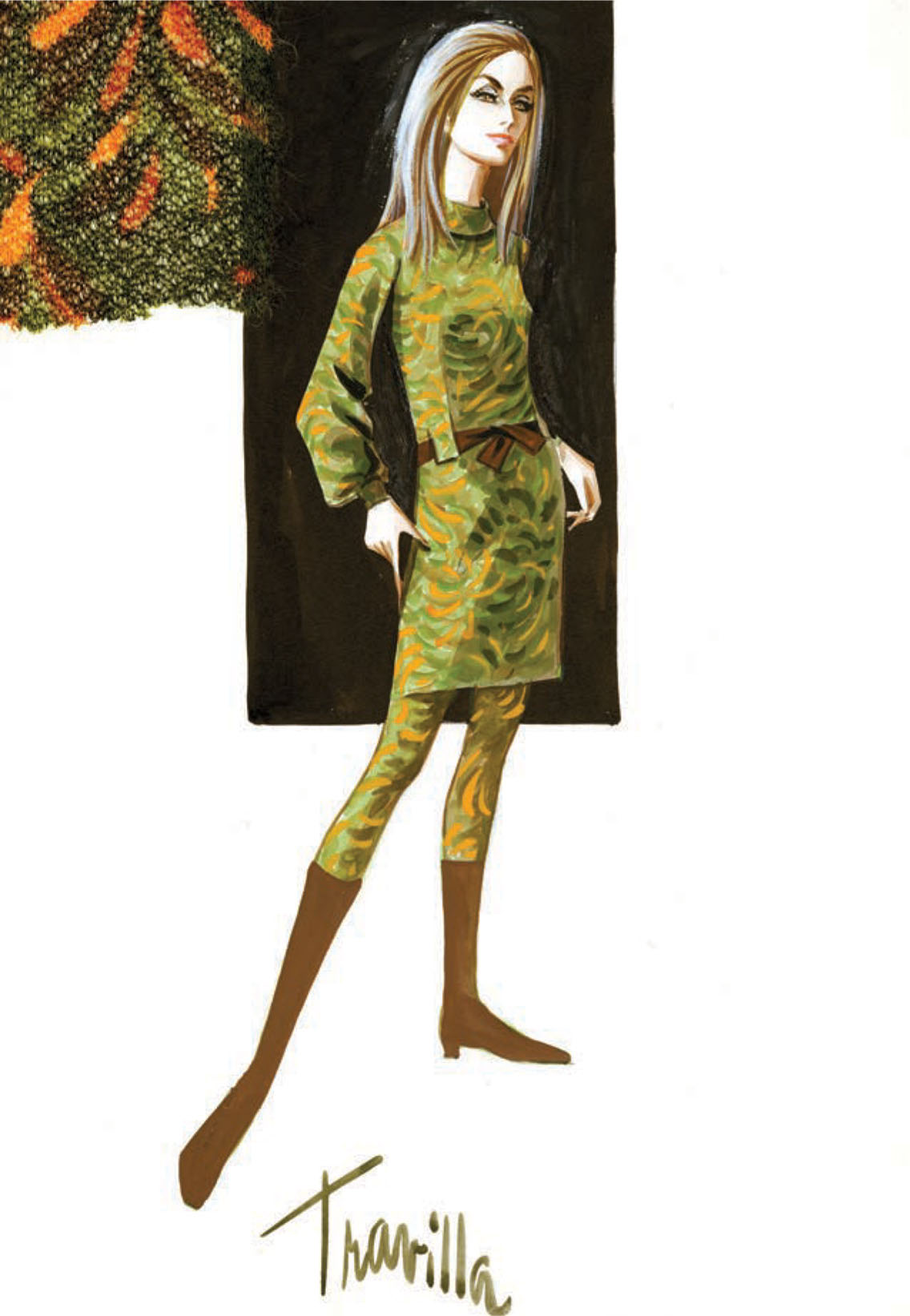

A William Travilla costume sketch for Barbara Parkins in Valley of the Dolls.

During the 1960s, Travilla also worked freelance in television, contributing designs for Diahann Carroll in Julia (1968–71) and for Loretta Young in The Loretta Young Show (1953–61). He also worked on films as a freelance designer, including The Stripper (1963) and Valley of the Dolls (1967). Director Mark Robson even tried to convince Travilla that he should play the designer husband of Patty Duke in Valley of the Dolls, telling the designer it would be good for his business. “But it’s the scene where she comes home and finds him naked in the swimming pool with a starlet, and I won’t do that,” Travilla told Robson. “The public will pay good money to buy my clothes. They don’t need to see my bare ass running across the screen.”

Barbara Parkins dressed by Travilla in Valley of the Dolls.

By 1971, Travilla found himself out of step with women’s taste in clothing. Jeans and polyester had taken over women’s wear, and they held no fascination for him. Travilla left Travilla Inc., and eventually moved to Spain. The country had a regenerating effect and he returned to the United Stares and reopened Travilla Inc. in the mid-1970s.

Beginning in the 1980s, Travilla’s work in television gained recognition, earning him seven Emmy nominations and two wins. Although the television miniseries Moviola (1980) included a featuring Marilyn Monroe’s early years as an actress, Travilla won the Emmy for his costumes for the “The Scarlett O’Hara War” episode. His other Emmy was for costuming the Ewing family on Dallas (1978–91). He found the schedules challenging, and he was required to be on set constantly to curtail possible mistakes. Nonetheless, television was where Travilla found his most success later in life, including the television movie Evita Peron (1981) with Faye Dunaway; the miniseries The Thorn Birds (1983) with Barbara Stanwyck; and the series Knot’s Landing (1979–93).

Costume design for Sharon Tate in Valley of the Dolls.

During his last decade, Travilla spent more time traveling, making trips to Africa, Egypt, Syria, and a return trip to the South Seas. He found influences for his ready-to-wear line everywhere he visited. A year after Drake’s death on June 20, 1989, Travilla learned that he had lung cancer. He died on November 2, 1990, in Los Angeles. Talking about his penchant for pleating with a reporter, Travilla once quipped, “When I die, I don’t want to be buried or cremated, just pleat me.”

(l-r) Barbara Parkins, Sharon Tate, and Patty Duke in Valley of the Dolls (1967).

Lucille Ball in Mame (1974). Costume design by Theadora Van Runkle.