DOROTHY JEAKINSDOROTHY JEAKINS

In her later years, Dorothy Jeakins described her father as cruel man, who kidnapped Dorothy from her mother when she was five years old and hid her in foster homes.

She said she never knew who her mother was, but she did know she was a couturier who made tea gowns. Even more tragically, she said that her father left her brother with foster parents, and never went back for him.

In a Los Angeles Times interview, she referred to her youth as “a Dickensian existence, cringing with fear in the shadow of a foster mother who took her frustrations out on her with whippings and threats to send her to reform school.” Dorothy would frequently be left alone, and at age seven, she would traverse Los Angeles on the city’s Red Line trolley cars and beg for handouts. “I wondered why I was alive, but somehow I kept on living,” she said. “I cried constantly, trying to comprehend who I was, and why fate had made me an unwanted child.”

Public records tell a somewhat different story. Dorothy Jeakins was born Dorothy Elizabeth Jeakins in San Diego on January 11, 1914. Her mother, Sophie Marie von Kempf, was a Danish immigrant who had two children, Allen and Katherine Willett, from a prior marriage. Originally from Yorkshire, England, Dorothy’s father, George Tyndale Jeakins, was a stockbroker who had immigrated to California in 1909. Soon after the birth of Dorothy’s little brother, Robert, the Jeakins marriage fell apart.

In a 1964 interview with Betty Hoag for the Archives of American Art New Deal and the Arts Project, Jeakins described attending a Montessori School in San Diego. “I learned to read and write before I was six, and to draw also,” Jeakins said. “And when I was in kindergarten I made a drawing of President Wilson, who had come to San Diego to speak at a war-bond rally, as I remember. Someone took me to see him and I made a drawing of him. They reproduced it in the newspaper. Someone showed me the newspaper, and I was astonished that it was good enough to be printed.”

In 1920, according to the census, Dorothy and Robert were living with their father in San Diego. By 1930, Dorothy and her father had moved to Los Angeles, settling in Carthay Circle, a Spanish Colonial Revival development bordering Beverly Hills. It is possible that by 1921, George Jeakins could have put Dorothy in foster care in Los Angeles, and then was reunited with her by 1930. In the Betty Hoag interview, Jeakins described attending Otis Art Institute as a twelve-year-old in a Saturday children’s class—not quite the stuff of Dickens. However, Robert W. Jeakins does disappear from the census. George never remarried and is not listed in any census as living with a woman.

“At Fairfax High I began reading plays, and it became a sweet escape into fantasy,” Jeakins said. “Sympathetic teachers encouraged my interest in drama, and during preparation for one school play, I was taken along on a trip to a costume house. I’d never seen a costume before, let alone hundreds of them. It became the turning point in my life.”

Jeakins won a scholarship to Otis Art Institute. She spent her weekends at the public library reading plays, and designing costumes for imaginary productions. “I’d take pencil and paper and draw complete wardrobes just by letting my imagination run wild,” Jeakins said. At the same time, Jeakins worked painting cells and animated backgrounds for Walt Disney at his original Hyperion Avenue studio for $16 a week.

Elizabeth Taylor presents Dorothy Jeakins with the Oscar for Best Costume Design for Joan of Arc (1948).

Ingrid Bergman in Joan of Arc.

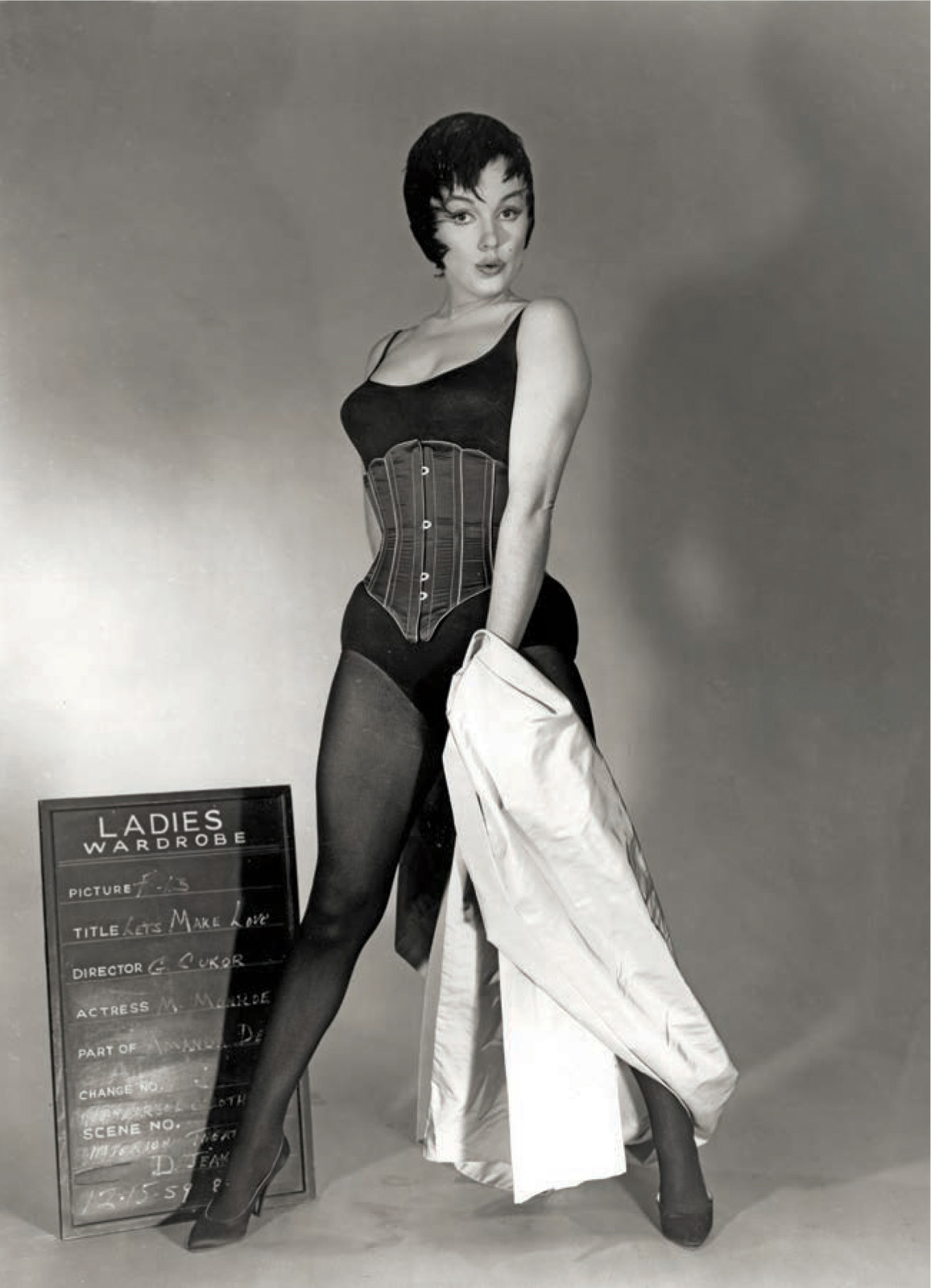

Marilyn Monroe in one of Dorothy Jeakins’s designs for Let’s Make Love (1960).

After leaving school, Jeakins worked doing illustrations for the Los Angeles City Planning Commission. Falling on hard times during the Depression, Jeakins worked for the Federal Art Project, painting for about a year before going into a division of lithography and printmaking. In 1937, Ernst Dryden hired her to work on costumes for Doctor Rhythm (1938). After Jeakins lost her studio position when the Federated Motion Picture Crafts went on strike, Jeakins went to work as a fashion illustrator at I. Magnin.

In 1940, Jeakins married Raymond Eugene Dannenbaum, the director of publicity for 20th Century-Fox. Dannenbaum changed his last name to Dane, and the couple had two sons. Dane was stationed in Paris during the war and never returned to Los Angeles, leaving Jeakins alone with the children. She later claimed that Dane stayed in Europe because his family had a castle there. Her explanation seems unlikely. Dane was born in Vallejo, California, on December 11, 1905, and was not European.

A Dorothy Jeakins costume sketch for Jean Simmons in Elmer Gantry (1960).

Jeakins’s layouts for I. Magnin caught the eye of 20th Century-Fox art director Richard Day. Day introduced Jeakins to director Victor Fleming, who hired her to sketch costumes for Barbara Karinska on his production of Joan of Arc (1948). Jeakins was shocked when Victor Fleming fired Karinska over the Fourth of July weekend. When Jeakins protested that she did not have the skill to finish the film herself, Fleming said that he believed that she could. “My life was altered in an instant,” Jeakins said.

A Dorothy Jeakins costume sketch for Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music.

The designs for Joan of Arc were awarded the first Oscar for costume design. Jeakins won another Oscar the following year for Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949). Jeakins believed that she did not deserve the Oscar for Samson and Delilah, because the costumes were done by what she described as a “costume congress of Cecil B. DeMille” including Edith Head, Elois Jenssen, Gile Steele, and Gwen Wakeling. She kept that Oscar in a closet.

Jeakins worked again on a team that included Edith Head, John Jensen, Ralph Jester, and Adele Balkan on DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956). Jeakins found the experience tempestuous. She described DeMille as “the most vicious man. He indulged in that awful process of making people appear to be naked in front of other people. At the end of the day I would end up in the men’s wardrobe, sobbing.” On the plus side, Jeakins said working with DeMille made her a perfectionist. “When you worked for DeMille, you became a perfectionist by necessity—unless you didn’t need your job,” she said. “It was the best training anyone could have. But it was far from sunshine and roses.”

During a costume consultation, Adele Balkan witnessed a clash between DeMille and Jeakins. “He wanted the garment to look identical to the sketch,” Balkan said. “You came as close as you could, but fabric and paper and paint are two different things, and he was not reasonable about that, or else he was doing it on purpose, I don’t know.”

Balkan accompanied Jeakins to the film’s location in Egypt. “I don’t think she really wanted to go to Egypt because of this, but she wasn’t about to miss out on the trip.” Jeakins left The Ten Commandments when the production returned to Los Angeles.

Jeakins made six movies with director John Huston and won her third Oscar for his Night of the Iguana (1964). Huston was the best director for using costumes as a tool for storytelling, according to Jeakins. For the tale of a defrocked minister leading a tour group through Mexico, Huston told Jeakins that “the tourists in the bus should look like they came from a mark-down sale at Orbach’s” and that “Deborah Kerr must look virginal, a fastidious Pilgrim walking through the world clothed in raw silk.”

Jeakins was one of the few Hollywood designers who worked freelance for her entire career. Occasionally she was left unprotected. For the classic film High Noon (1952), starring Grace Kelly and Gary Cooper, Jeakins received no screen credit. “The action all took place within an hour, a ‘small’ job, I suppose,” Jeakins said. “I never thought to ask [producer] Stanley Kramer for screen credit for my work, therefore none was given—as it should have been. A lesson learned.”

Jeakins successfully costumed Marilyn Monroe in Niagara (1953) as a vixen plotting her husband’s murder. When Ray Cutler (Max Showalter) spies Rose (Monroe) in an eye-popping dress, he asks his wife, Polly (Jean Peters), “Why don’t you ever get a dress like that?”

“Listen, for a dress like that, you’ve got to start laying plans when you’re about thirteen,” Polly tells him.

When Monroe and Jeakins collaborated again on Let’s Make Love (1960), Monroe was unhappy with some of Jeakins’s designs. Eventually, Marilyn replaced the outfits she did not like with pieces from her personal wardrobe. Jeakins and Monroe tried again on John Huston’s The Misfits (1961), and nothing improved. “Although I really feel I should be replaced—I will continue with your clothes for The Misfits because they are under way and nearly ready to fit,” Jeakins wrote to Monroe. “If you like them, I will see them through to completion. If you are disappointed, someone else can then take over. I am sorry I have displeased you. I feel quite defeated—like a misfit, in fact. But I must, above everything, continue to work (and live) in terms of my own honesty, pride, and good taste.” Ultimately, Monroe chose Jean Louis to design The Misfits.

From 1953 to 1963, Jeakins designed productions for the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera Company. She was nominated for Broadway’s Tony Award for Best Costume Design for Major Barbara (1957) and Too Late the Phalarope (1957) and for The World of Suzie Wong (1959). In 1962, Jeakins won a Guggenheim grant to study in Japan. She became interested in ethnic and tribal costumes and worked as a curator for the textile and costume collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In 1966, in addition to designing the film Hawaii, Jeakins also had a small role as Julie Andrews’s New England mother-in-law. Jeakins believed she was cast because she had “a tired face.” Jeakins’s last film was John Huston’s The Dead (1987).

A wardrobe test for Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music.

Even through a life of introspection and melancholy, Jeakins was able to see beauty. “In the middle of the night, I can put my world down to two words: make beauty. It’s my cue and my private passion,” she said. Jeakins died on November 21, 1995, in Santa Barbara, California. She was 81.

Faye Dunaway in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968).