THEADORA VAN RUNKLETHEADORA VAN RUNKLE

Theadora Van Runkle came into the world on March 27, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as Dorothy Schweppe. She was the daughter of Eltsey Adair and Courtney Bradstreet Schweppe, a son of the Schweppes carbonated drink family.

Her parents, who were unmarried, did not stay together, and when she was two years old, Dorothy moved to California with her mother. She was raised in Beverly Hills, and later dropped out of Beverly Hills High School.

She married Robert Van Runkle when she was still in her teens. They had two children—Maxim and Felicity. Maxim’s birth somehow caused Van Runkle to tap into her creativity. “The minute I got home from the hospital I started teaching myself to paint and draw,” Van Runkle said. “Then I began going downtown and getting jobs as an illustrator. While I was freelancing, I always made my own clothes, and made clothes for friends, cut friends’ hair in new styles, and just played at being a talent.” During this time she changed her name to Theadora.

While drawing ads for I. Magnin one afternoon in 1964, Van Runkle decided she “was through with advertising,” she said. “I was bored to tears with it and something else had to happen.” Van Runkle met Dorothy Jeakins at a party, and Jeakins told her she needed a sketch artist. “The next day I went to work for her—for a month,” Van Runkle said. “She let me go because I think she didn’t like that I was such a good artist. She felt threatened.”

But Jeakins was responsible for Van Runkle’s big breakthrough from sketch artist to costume designer. Jeakins had designed The Sound of Music (1965) for director Robert Wise, and she believed she was going to be hired to design The Sand Pebbles (1966). Instead, Wise chose designer Renié Conley, whose specialty was ethnic costumes. Conley hired Van Runkle as a sketch artist and put her in a little office.

“One day Jeakins came to see Conley,” David Chierichetti said, “and she saw Theadora at work. She walked up behind Theadora and made a motion as if she was going to hit her, since she believed Van Runkle had gone to work for the enemy. What Jeakins didn’t realize was that Van Runkle had a mirror on her desk and that she saw Jeakins come up behind her with her hand raised. Van Runkle ducked, and Jeakins was embarrassed. In order to sort of make it up to Theadora, she turned over Bonnie and Clyde (1967) to her.”

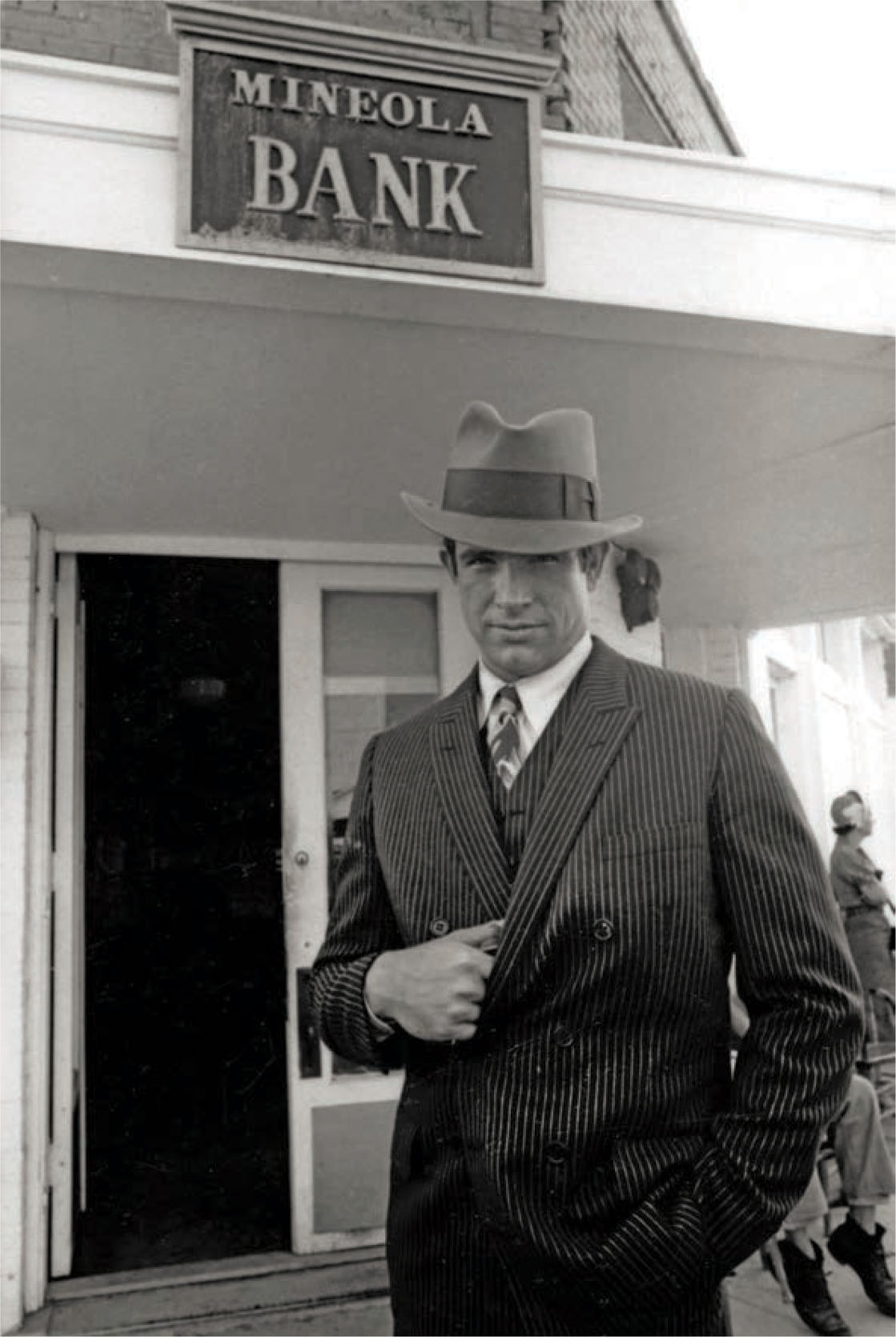

“I’d never designed anything before,” Van Runkle said of Bonnie and Clyde. “I never went to design school. I never went to art school. But I knew fashion. I knew style. I knew construction. I sewed by hand and by machine. I learned construction from Vogue patterns.” Most of Clyde’s suits—chalk-striped, double-breasted suits were patterned after archival footage of Pretty Boy Floyd. Dunaway was not convinced that Van Runkle’s maxi skirts and berets were right for her. “Faye thought I didn’t care,” Van Runkle said. “Faye thought I was trying to make her ugly.”

The “Bonnie and Clyde look” took the country by storm. Milliners became busier than ever making berets. Suddenly, the miniskirt was no longer the rage and the maxi skirt came in. Van Runkle’s comments about her sudden success led to resentment from other costume designers, who had spent years working as costumers and assistants to learn their craft and work their way up. “I knew for all of my professional life I’d be doing this,” Van Runkle said. “But I did nothing to get there. I knew it would happen by a miracle. It was written in the stars.”

Bill Thomas, who was nominated for an Oscar for The Happiest Millionaire (1967) against Bonnie and Clyde, said of his contender in the press, “I expect Bonnie and Clyde to win the Oscar for Best Costume Design,” Thomas said. “I’m not saying it’s right, I am simply saying it’s what will probably happen. You see, most people who vote aren’t really students of design. They are in no position to judge. They’ve seen Bonnie and Clyde, know that the costumes are affecting the fashion scene today, and probably won’t consider any more than that. It’s unfair because kids are going out and buying Bonnie and Clyde costumes, not because they dig the designs, but because they want to emulate the lead characters in the movie. Had Bonnie and Clyde lived a century earlier, you’d see teenagers going around dressed in bustles and long gowns now.” Notwithstanding Thomas’s prediction, John Truscott took home the Oscar for Best Costume Design for his work on Camelot (1967).

Faye Dunaway and Theadora Van Runkle during the making of Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

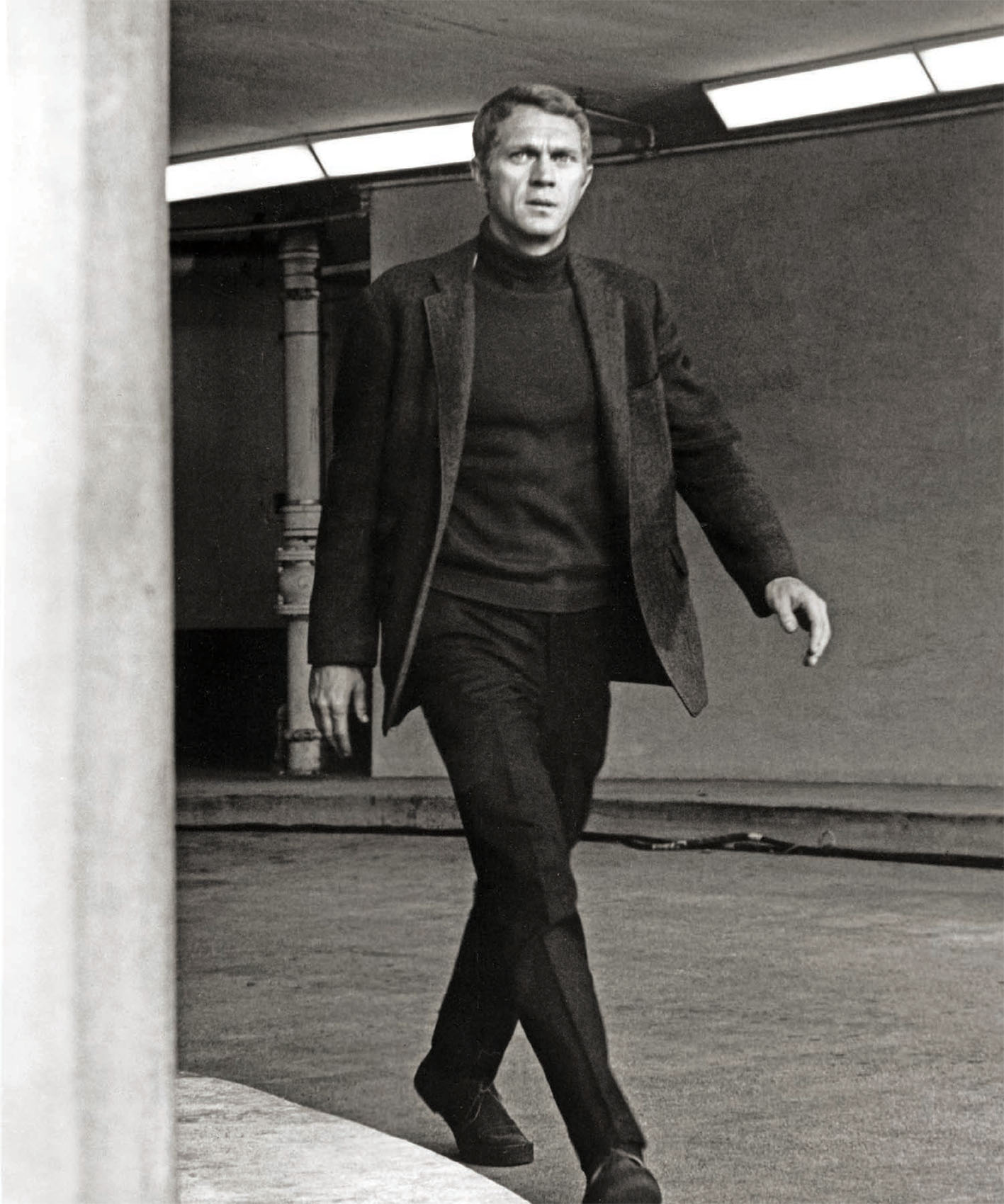

In The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), Van Runkle created twenty-nine changes for Faye Dunaway as a hip insurance investigator, playing opposite Steve McQueen as a wealthy businessman and bank robber. Van Runkle used what she called “method accessorizing” to help enhance Dunaway’s character, who was trying to set a trap for McQueen. “It’s an entire look,” Van Runkle said at the time. “For one scene where Faye is obviously going to have a sexual encounter, I designed a dress of diaphanous flesh-colored chiffon with just one button at the neck. We worried about jewelry for a long time. Faye wanted to wear something that would symbolize control as a counterpoint to her passion. So I finally got a massive antique cameo pin, and we combined that tremendously sensual dress with that in-control, almost puritanical piece of jewelry.”

Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde.

Van Runkle envisioned wide-brimmed hats and braided and upswept hairpieces for Dunaway in The Thomas Crown Affair and knee-length skirts. “But Faye wanted the skirts to be right up to her crotch. We got into a knock-down, drag-out over it and she won.” In an interview a few years later, Van Runkle named Dunaway as one of the few in the industry who truly appreciated her work.

During the 1970s, Van Runkle’s old Hollywood sensibility was showcased in Myra Breckinridge (1970) with Raquel Welch; Mame (1974) with Lucille Ball; and New York, New York (1977) with Liza Minnelli.

Steve McQueen in Bullitt (1968).

Liza Minnelli in New York, New York (1977).

When the successful Broadway musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982) was adapted for the screen, Van Runkle gowned Dolly Parton as the madam. Parton “knows she’s got gifts,” Van Runkle said, “and with her pale hair and white skin, she looks so wonderful in Dresden colors, in bisque. She’s like ivory, pearl, crystal. She reminds me of all the great French beauties, of Du Barry and Marie Antoinette.” For Parton’s first number in the film, Van Runkle designed a gown that was an homage to Mae West. But after the costume tests were done, Van Runkle realized it did not make enough of an impression. She made a new sketch. “It’s gorgeous,” director Colin Higgins told her. “Do you want it? It’s going to cost a fortune,” she said. “Do it,” Higgins told her. The low-cut red silk chiffon gown with thousands of tiny hand-stitched red, blue, and orange bugle beads made up $7,000 of the film’s $60,000 costume budget. It was dubbed “Miss Mona aflame with passion.”

Van Runkle spent her later years painting, attending art classes at UCLA, and doing sporadic work in films. When she made I’m Losing You (1998), a contemporary film by Bruce Wagner, Van Runkle lamented the changing role of costume designer. “Nowadays, movie makers want to spend no money on costumes and they want it to look like the great, golden age of costuming,” she said. “I didn’t have a concept for costumes because I didn’t have any money.” Van Runkle said she worked “with what I could cull from people’s closets, my own closet, and bits of fabric to put things together.”

Van Runkle married photographer Bruce McBroom on December 24, 1974, and the couple divorced December 29, 1982. She also taught at the Chouinard Art Institute and the Otis Parsons School.

“I know that everyone is supposed to fight, scream, and push to the top,” Van Runkle said. “Be a winner, not a loser. But I’ve seen enough winners in the movie industry and I didn’t like what I saw. I’m against the kind of thing where you are so ambitious that you lose out on becoming a person. I just want to grow old, wise, be domestic, cultivate my personal life, love my kids, try not to drop names, and get a little respect out of people for my designs.” Van Runkle died of lung cancer on November 4, 2011, in Los Angeles. She was eighty-three.

A Theadora Van Runkle costume sketch for Raquel Welch in Myra Breckenridge (1970).

Jane Fonda in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969).