Donfeld was born July 3, 1934, in Los Angeles, California, as Donald Lee Feld. His earliest memories of drawing were in grammar school.

His teachers encouraged his artistic abilities through high school, but Donfeld planned to be a veterinarian. When a donkey Donfeld had nursed for two years died during a classroom experiment, he was crushed, and realized he did not have the courage to watch something he loved die.

Donfeld studied commercial design for two years at the Chouinard Art Institute, but became more interested in fashion. In 1953, an executive from Capitol Records was giving a lecture at Chouinard and saw Donfeld’s work. He offered Donfeld a position as Assistant Art Director, and ultimately Donfeld designed the album covers for some of the most popular movie soundtracks of the day—Oklahoma! and The King and I among them.

“He was the new guy at Capitol Records coordinating the albums and the artwork, and nobody wanted to work with Frank Sinatra or Judy Garland because they felt they were so difficult,” said Donfeld’s friend Leonard Stanley. “Donfeld was not impressed by celebrity; he treated everyone equally. Judy and Frank adored him.”

Donfeld had been at Capitol for several years when he found out that his assistant was making more money than he was. Donfeld approached his bosses and asked for a raise. They decided to let him go instead. Donfeld called Sinatra for help. The singer’s secretary explained that he was in Las Vegas, but said she would give him the message. Donfeld was sure he would hear nothing. Within twenty minutes, Frank Sinatra called back and said “What’s up kid?” “I’ve just been fired from Capitol Records and I don’t know what I’m going to do with the rest of my life,” Donfeld told Sinatra. “Give me a half an hour,” Sinatra said. Half an hour later the phone rang and it was Sinatra. “You have an appointment with [producer] Arthur Freed at MGM at 12:30 and you have an appointment with [director] Vincente Minnelli at 1:30,” Sinatra said. “Frank created Donfeld’s entire second career, so you could never say anything against Frank Sinatra to Donfeld,” Stanley said. “For the rest of his life, Donfeld always referred to him as ‘Mr. Sinatra’ in front of other people.”

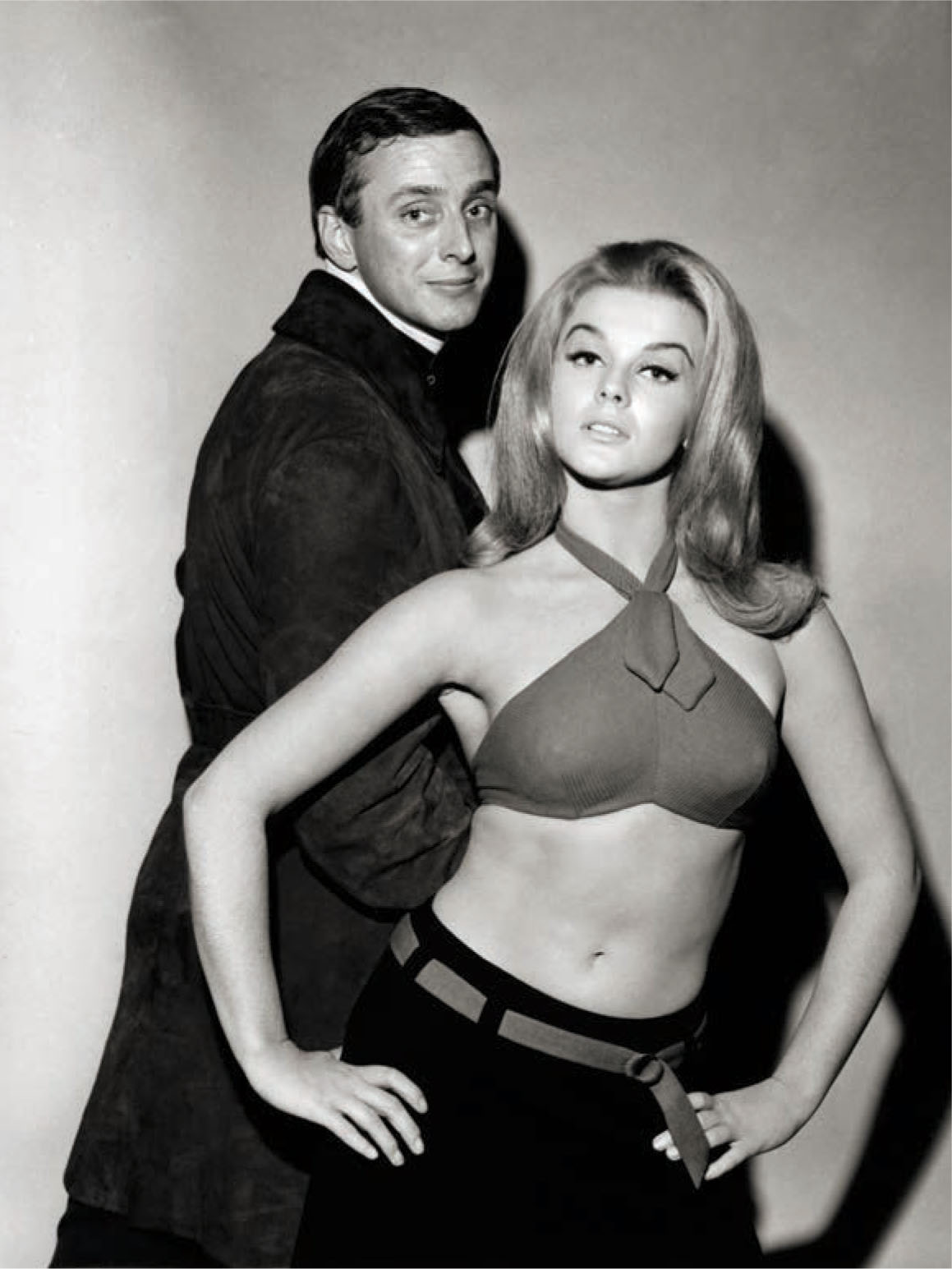

Donfeld with actress Ann-Margret.

Donfeld was hired as a sketch artist on Spartacus (1960) at MGM. Minnelli also put him to work as costume coordinator and assistant to the producer on a number being prepared by MGM for the Oscars that year—Maurice Chevalier singing “Thank Heaven for Little Girls.” When Minnelli became ill, he asked Donfeld to take over production entirely, and the number was the highlight of the telecast.

Donfeld was hired by producer Jerry Wald at 20th Century-Fox as a special visual consultant to color consultant Leonard Doss on The Best of Everything (1959) and later, The World of Suzie Wong (1960). Costume designer Mickey Sherrard said that Donfeld was fascinated with anything to do with wardrobe and quizzed costume designer Adele Palmer about how fabrics photographed.

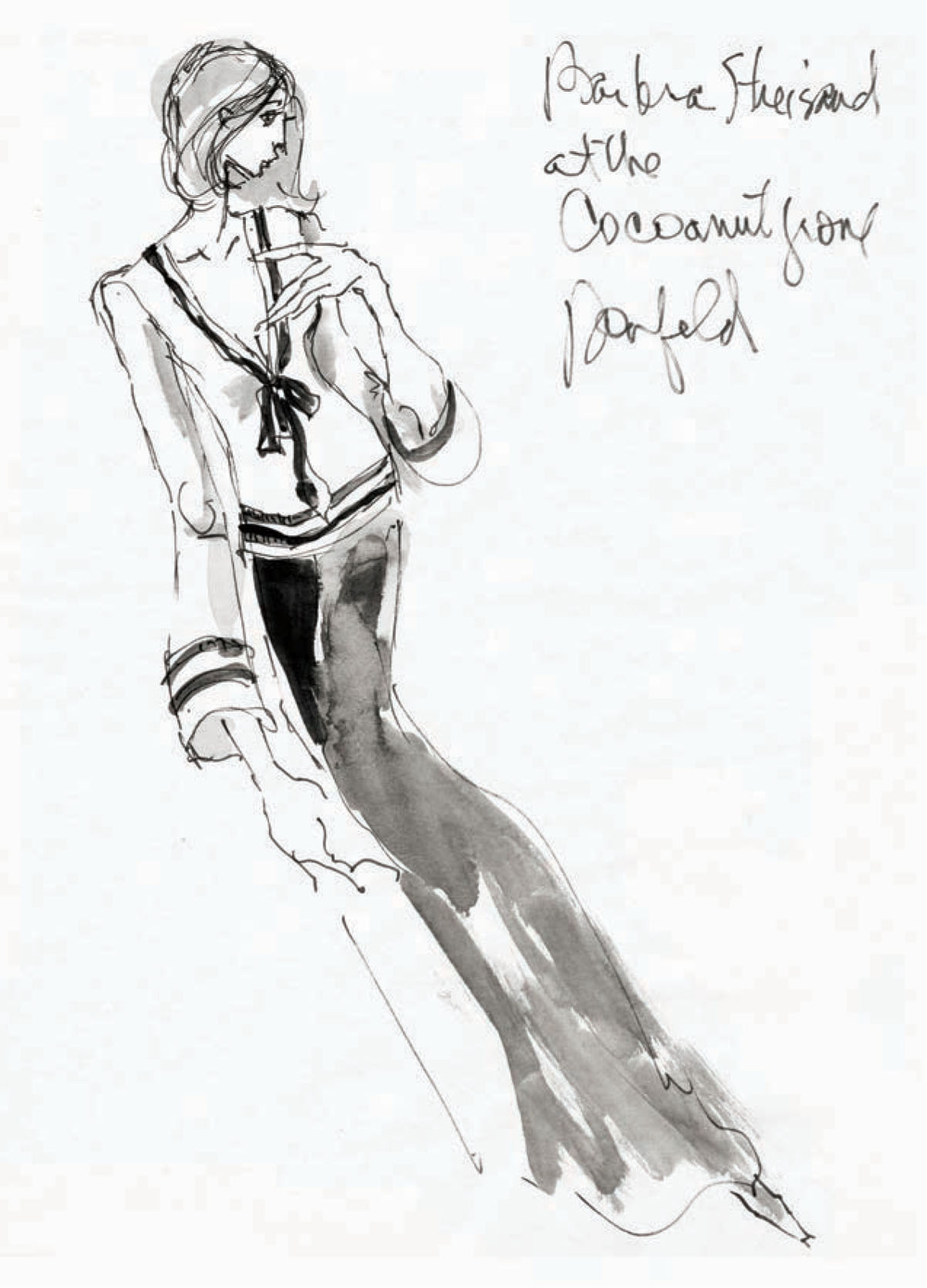

Donfeld’s sketch for Barbra Streisand’s appearance at the Cocoanut Grove (1963).

Donfeld then signed a five-picture deal with 20th Century-Fox to design costumes. His first film was Sanctuary (1961) with Lee Remick, and by 1962, he received his first Oscar nomination for Days of Wine and Roses. Donfeld also carved out a niche for himself designing for television, cabaret, and Las Vegas appearances of Barbra Streisand and Nancy Sinatra.

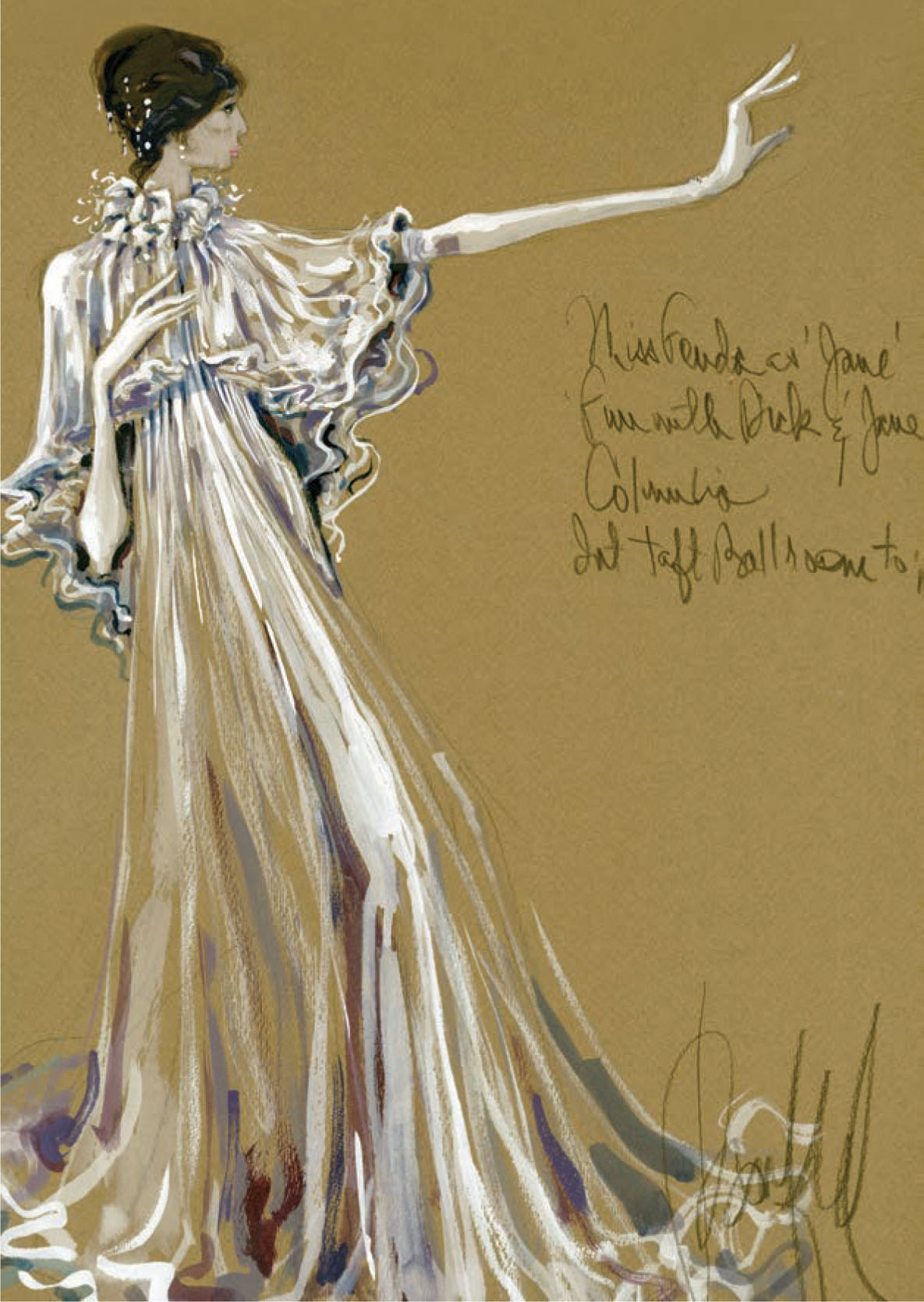

For They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), about a marathon dance in 1932, Donfeld decided the characters would not have had enough money to buy new clothes, so his designs started with clothes that would have been fashionable in 1929. Donfeld played authentic 1920s records during the fittings with Jane Fonda to help the actress find her character of Gloria. He even played an “If Gloria . . .” game with Fonda. “If Gloria weren’t a hooker, what would she be?” he asked Fonda. “A carhop,” she answered. “If she were a singer, whom would she idolize?” “Ruth Etting,” Fonda replied. Finally, one day Fonda looked in the mirror and said, “I am Gloria!” Donfeld’s clothes received glowing notices from critics, who found them wholly authentic to the Depression era. “Not one costume sent people out of the theater wishing for one like it,” Donfeld said. “But when those characters spoke, the audience listened. People who acted like slobs looked like slobs.”

Donfeld’s sketch for Bette Davis in Dead Ringer (1964).

After ten years in the industry, Donfeld became the second-highest-paid costume designer in the business, after Irene Sharaff. Donfeld’s fees for film work were $1,000 a week and up by 1970. That same year, Nancy Sinatra paid him $10,000 to design her wardrobe for her appearance at Las Vegas’ International Hotel.

In his house in Benedict Canyon, Donfeld hosted a kind of weekly salon for celebrities, including Tuesday Weld, Jacqueline Bisset, Michael Sarrazin, and David Hedison. “He was very good at making things quite comfortable and cozy,” Jacqueline Bisset said. “His house was delightful. It was constantly changing. He made objects interesting. He always had big sheepdogs for as long as I knew him. He was so big and had such a physical presence. He was a little awe-inspiring, which I think he thoroughly enjoyed.”

Donfeld’s sketch of Jane Fonda in Fun with Dick and Jane (1977).

Bisset and Donfeld became good friends and collaborated on a number of films, including Jules le magnifique (1977), Who Is Killing Great Chefs of Europe? (1978), and Class (1983). “I asked for him to design for me in The Grasshopper (1970),” Bisset said. “He understood the body and he subtly used darts and the placement of seams to help it look better,” she said. “My character in The Grasshopper changes from the beginning, when she is a little young woman from an average background, and she takes her chance in Vegas. He did a really good job. I enjoyed working with him because he was such a colorful character. He could be terribly funny if he didn’t like what you were wearing. He would throw his hands up in the air and gesticulate and make noises. There was no hiding his dislike of things.”

Lamenting what had happened to the Academy Awards after he stopped coordinating the fashions, Donfeld was brutal. Of Barbra Streisand in 1969, he said, “Her dress looked like a pinball machine with all those dots on it, like you could put a quarter in her mouth and she’d light up.” Some actresses in Hollywood did not forget his criticisms easily, especially when choosing or approving a designer for their next project. Donfeld’s acerbic critiques cost him a number of projects.

“He adored Jane Fonda and thought she was a very important woman,” Bisset said. “He was always going on about what a valuable person she was and how she didn’t have an unimportant thought.” But even Fonda could not escape Donfeld’s ire when she did not request him for Julia (1977) after they had worked together on Fun with Dick and Jane (1977). Fonda wrote and explained to Donfeld that “The fact that Anthea [Sylbert] is doing Julia has nothing to do with me. It was a fait accompli. By the time I met with [director Fred] Zinneman to discuss such matters, he informed me that he had already engaged Anthea, as well as a hairdresser and that was that.”

Bisset also saw the temperamental side of Donfeld when she was unable to get him hired for a job. “He got very grumpy,” Bisset said. “I couldn’t understand that because he must have known that one doesn’t have the power to request people very often. And he was not a cheap person to employ, so there was the budget to consider. He got very upset with me. He didn’t tell me directly, but he got very vicious, I was told. We managed to get through that.”

Donfeld was nominated for an Oscar for Prizzi’s Honor (1985), starring Jack Nicholson, Kathleen Turner, and Anjelica Huston. Huston “had a hand in many aspects of my work,” Donfeld said. “I think I bewildered her a bit at the outset, but she never got in my way. She never resisted nor played the director’s daughter.” Director John Huston suggested a “Schiaparelli pink” swath of fabric across Anjelica’s black taffeta dress. When the film was released, Donfeld received a note from designer Dorothy Jeakins. It read, “On the nose and all wonderful.”

Donfeld’s sketch for Natalie Wood in Brainstorm (1983), the actress’s last film.

In the mid-1990s work slowed down for Donfeld and he began experiencing financial problems. “It’s those damn business managers that everybody gets mixed up with,” Stanley said. “Somebody took him to the cleaners. He thought he was making so much money, but couldn’t understand why he was so broke.”

“I think his life became very difficult for him near the end,” said costumer Margo Baxley. “Unfortunately, Don was so bright and articulate with his pen. He would send notes, and sometimes he was not as discreet as he should have been, and I think it came back to cause him problems in the end. So I don’t think his last few years were very happy.”

“Somehow our relationship ended up in a kind of nondescript way, mainly because I was not able to request him and I was upset for myself, being told that he was angry,” Jacqueline Bisset said. “He had some moments of financial problems that I tried to help him with. I was one of the few left after things got torn down and he became impossible.” Donfeld died at the home of his brother Richard in Temple City, California, on February 3, 2007, at the age of seventy-two.

Though things went wrong later, Donfeld expressed a great optimism in the happier times of the mid-1960s. “In my work, I try to collect all my thoughts and say to myself, ‘Be grateful for what you have and what you are and more than grateful to those who have helped you in difficult days,’” Donfeld said. “I keep reminding myself of the wonderful, encouraging people around me. Regret is something I don’t have time to consider.”

Donfeld’s sketch for the dress Natalie Wood was to wear to the opening night gala of her stage debut in Anastasia in Los Angeles. Unfortunately, Wood died before the show opened.