PAUL ZASTUPNEVICH AND BURTON MILLERPAUL ZASTUPNEVICH AND BURTON MILLER

It seems unlikely that the two men who would define the fashion looks of the Hollywood disaster epic craze of the 1970s would grow up nearly side by side in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Paul Zastupnevich, the designer who worked for disaster impresario Irwin Allen and Burton Miller, who designed the Jennings Lang disaster films for Universal, both knew how to fan fashion flames.

Paul Dimitrovich Nicholiavich Ivanovich Fidorovich Gregorovich Zastupnevich, was known professionally as Paul DNIFG Zastupnevich, or as his friends called him, Paul Z. He was born on Christmas Eve in 1921 in the smoky town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, a steel suburb of Pittsburgh.

Zastupnevich began designing with the most important, and most available, of subjects—his mother. “My grandmother was a diva,” said Zastupnevich’s niece Marinka Sjoberg, “and she was the most important person in the family by far.” Zastupnevich also turned to his sister, Olga, for inspiration. “He wanted to dress my mother up like a Hollywood movie star because that was the biggest ‘movie star’ in his life,” said Sjoberg.

Zastupnevich studied at Carnegie Tech and earned a bachelor’s degree from Duquesne University and a master’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh. While in the Army, he helped found the Fort Benning Theatre Guild to put on shows for the servicemen, and designed costumes for their productions. He returned to Pittsburgh, and designed costumes for the Pittsburgh Civic Ballet. Relocating to Los Angeles, he spent six years at the Pasadena Playhouse as a student actor, costume designer, and director of stage productions, earning a degree in theater arts.

In the late 1950s, Zastupnevich starred under the name Paul Kremin at the Riverside Tent Theater in North Hollywood in the musical Plain and Fancy. His costar was Jeanne Cooper, who at the time was the wife of Rhonda Fleming’s agent, Harry Bernsen. Fleming needed a gown for the Sportsman’s Award Show and had tried to engage Edith Head to do it, but she was unavailable. Cooper suggested that Zastupnevich design the gown for Fleming.

Fleming was so pleased with the design that she asked Zastupnevich to design for her next film, The Big Circus (1959), for producer Irwin Allen. Zastupnevich got the script from Allen and created a group of sketches overnight. He made a red-and-white striped presentation folder with a clown’s head and IRWIN ALLEN’S THE BIG CIRCUS emblazoned across the cover. Zastupnevich could not have known at the time how much packaging and presentation meant to Allen, who himself had to package proposals to investors. It was a large part of winning Allen over. Zastupnevich was hired.

“If there was ever an egomaniac, it was Irwin Allen,” Zastupnevich said. “In many ways, he was a remarkable man. He was the ultimate salesman. I should know for I used to accompany him when he would make a ‘pitch’ presentation to the networks. I was his overworked, underpaid ‘go-fer.’” After The Big Circus, Zastupnevich became Allen’s full-time designer for all of his productions at 20th Century-Fox.

On December 16, 1967, Zastupnevich’s brother-in-law, Charles Yurkew, was stabbed and killed in his Pittsburgh home by his own cousin. Zastupnevich’s sister, Olga, and her daughter, Marinka, were home at the time. “Paul felt so responsible for my mother that he immediately flew out, swept us up, and flew us out to California,” Sjoberg said. “He never let us out of his sight again. My mother was traumatized by the event, and he wanted her to know that she was protected. He became like a father to me. He sacrificed his entire life for family. Whatever relationships he could have had, he didn’t. He didn’t have time, he was always working. Between locations and the studio, sometimes he worked on three or four shows at a time.”

The cast of the television series Lost in Space (1965–68). Costume design by Paul Zastupnevich.

A 1950s Burton Miller costume sketch for Monica Lewis.

Some of Zastupnevich’s most well-known work was for Allen’s television shows. Zastupnevich won the Costume Designers Guild Award for “Best Dressed TV Series” in 1968 for Lost in Space, and again in 1970, for his work on Land of the Giants. “We went from the first year (where) we used a very heavy weight silver fabric, which was quite difficult to work with,” Zastupnevich told writer Flint Mitchell about Lost in Space. “It was basically used in fire-fighting outfits with a heavy silver. The following year, when the twenty-four-carat silver jersey came out, we switched over to the suits, because (in) those you could bend over, and they wouldn’t crack, and they wouldn’t be stiff, and they wouldn’t be difficult to work in. Out of the two types of suits that we featured in Lost in Space, I still like the first one, because they had more of a futuristic, spacey feeling. I just felt that the twenty-four-carat jerseys was almost going into musical comedy–type of costuming.”

Because Land of the Giants involved a group of survivors of a suborbital passenger craft, the cast wore the same outfits for the entire first season. “When we started the thing, they only had one outfit, no doubles,” Zastupnevich said. “They got sick of wearing the same thing. Finally, the whole cast said, ‘For God’s sake, we have luggage aboard!’ And Don Matheson said, ‘I’ve got so much money, and Deanna’s [Lund] traveling around the world, and Heather [Young] should have a spare uniform somewhere along the way. So finally they convinced Irwin that they could have a change.” The costume budget was so tight that Zastupnevich did not have enough money to have boots made to match Deanna Lund’s outfit. So he took boots home and painted them. “I might have gotten into trouble with some local (union), but we got it on the screen and she was quite happy,” Zastupnevich said.

“In The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Stella Stevens wore a Jean Harlow inspired gown,” Zastupnevich said. “I had forewarned Stella that Irwin would be a prude about the cleavage she was exposing in the front. But I felt that since she was playing a retired hooker, married to a retired cop (Ernest Borgnine), we would brave his screams and bellows. When he carried on so that I knew he would throw out the dress if I didn’t act quickly, I dashed over and withdrew a gaudy diamond beige clip and dropped it into the valley of cleavage. Irwin and Stella both shouted—one with approval and one with protest. I finally managed to placate Stella and I must say she served me smashingly in the white satin number. When Shelley Winters spied Stella wearing the dress, she bellowed, ‘Gee, you’re wearing the type of dress I always wore.’ Stella, with her hands on her hips, whipped back, ‘Yeah, dearie? What year was that?’”

In preparing Winters’s New Year’s dress for The Poseidon Adventure, “I created for her a smoke chiffon cocktail dress that any Yiddish matron would wear to her mitzvah. Shelley had gained some weight, but Irwin Allen wanted more poundage, so we had to improvise weight pads and even pad her out to a zaftig matron. The only peril in this, we found out later, is when Shelley had to get into the water tank, she wouldn’t sink. She merely dove to the bottom and popped up like a floating cork.” Zastupnevich had to attach weights to her frame to make her submersible.

Paul Zastupnevich

For The Towering Inferno (1974), Zastupnevich created a daring dress for star Faye Dunaway. “The dress was cut to here and slit to there and she would have fallen out of it, but we had her taped,” Zastupnevich said. He told the director Dunaway should not sit in the dress and that she should stand or lean against a pole. “Whatever you do, don’t have her bend over or you’ll give us problems,” Zastupnevich told him. “Would you know he double-crossed me and put her in a chair from the beginning! But she held herself up and the tape held.”

“Just after the show came out, I began to read reviews, and one critic chastised me for putting Faye Dunaway in a dress for going to a fire,” Zastupnevich said. “He wrote to me in the article, ‘Why would she wear that kind of dress to a fire?’ I was so furious, I sat down and wrote a scathing letter. I said, ‘What makes you think she was going to a fire? She was going to a cocktail party to seduce her boyfriend on top of the Empire State Building, practically. She didn’t know she was going to a fire! If she had known, she would have worn overalls that were fire retardant, not the chiffon dress!’”

Deanna Lund in the television series Land of the Giants (1968–70). Costume design by Paul Zastupnevich.

After retiring to Palm Springs, Zastupnevich operated the clothing shop at the House of Z, his sister Olga’s beauty shop and boutique. Zastupnevich died on May 11, 1997, in Rancho Mirage, California. “I heard jokes about his costumes—the silver suits on Lost in Space, or jokes about how Paul must have designed Irwin Allen’s leisure suits,” Sjoberg said. “But that was all cool during the time. Guys were wearing orange and pink and lime-green polyester leisure suits. Paul was well known for his velvet tuxedos. Ten years ago that was so out of style, but now today, it’s cool again.”

Paul Zastupnevich’s costume sketch for Stella Stevens in The Poseidon Adventure (1972).

While Allen reigned as the king of disaster films at 20th Century-Fox, across town Jennings Lang was producing a string of disaster films at Universal. His costume designer was Burton Miller, who was born in Oakland, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on January 17, 1926. Miller graduated from Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1949 and then attended Parsons School of Design in New York. His entrée into the design world came via another Pittsburgh native, Broadway singer Lisa Kirk.

Singer Monica Lewis discovered Miller’s work when her brother, Marlo, was producing the television show Toast of the Town, and Kirk was a guest. “I called Burton and we made a date at a pharmacy that had a soda fountain,” Lewis said. “We both ordered coffee and split a piece of pound cake. I figured he didn’t have any money, not knowing that his family did. But I thought ‘here’s a kid hawkin’ clothes’ and I insisted we go dutch. And we never shut up. We talked and talked for hours.”

From that point on, Miller designed all of Lewis’s clothes for her nightclub and television appearances. Lewis did not know that Miller’s father owned a large car dealership in Pittsburgh and his family was well off. “I didn’t ask if Burton was gay, but I knew,” Lewis said. “But who cares? My parents taught me tolerance about everything.” One day Lewis received a call from Miller’s father. “I know how much my son loves you and I have something to offer you,” he told Lewis. “I know you’re busy and I know you’re working, but you could still do what you do. I would love it if you would marry my son because I know it would make him very happy and make us very happy, and I will give you a million dollars.” Lewis was a little stunned, to say the least. “I said, ‘Well, as much as I love Burt, I am in love with somebody else,’” Lewis said. “I thanked him very much and told him there was no need to give me a million dollars because there’s nobody I’d rather spend my life with than Burton, as far as a pal, but I might become engaged soon. I made up a whole story on the phone and he was very disappointed.”

Lewis hung up the phone and called Miller. At first he was furious when he heard what his father had done. Then he laughed and told Lewis that she should have taken the money. “I told Burton that money wouldn’t last us three months,” Lewis said, “and he agreed.” Lewis still is not sure what prompted the proposal. “I’m sure his mother knew he was gay. His father may have had an issue with Burton being gay, but he still loved his son. He was trying, in his own way, to protect his son.”

After Lewis married Universal film producer Jennings Lang in 1956, she invited Miller to move out to Los Angeles. Miller closed up his New York apartment and lived with the Langs for nine months, until he could join the Costume Designers Guild. Miller was signed by Revue Studio, which was owned by Universal. Miller designed for Revue’s shows, including The Alfred Hitchcock Hour; The Investigators with Mary Murphy; Checkmate with Julie London, Claire Bloom, Clair Trevor, and Joan Fontaine; Thriller with Judith Evelyn. He also designed a 1920s wardrobe for Maureen O’Sullivan to wear on an Alcoa Hour with Fred Astaire.

“Burton was very inexperienced. He learned by doing,” said Helen Colvig, who worked at Universal with Miller. “I’m sure [wardrobe supervisor] Vincent Dee helped him a great deal because Vincent helped all of us. If we could fly on our own, he wouldn’t interfere. But if we were having trouble getting things done, he always intercepted for us.”

Miller dropped in on the Langs after a fitting with Ann-Margret for Kitten with a Whip (1964). The trio was having a drink before dinner, and Miller sat Jennings and Monica down and said, “I’ve got to tell you guys something you won’t believe. I had a fitting with Ann-Margret, and I fell madly in love. It turned me on so much, I was blushing. It almost convinced me that I could be straight.” Lang told Miller, “Well, that’s the effect she has on the public.”

Miller occasionally shared duties with Edith Head on Universal projects. When he was assigned to Earthquake (1974), he costumed all the stars except Ava Gardner, who had requested Head. “Ava just wanted to look as good as she could,” Monica Lewis said. “She said to me, ‘I’m not going on any diet. They can drape me or do something. It’s too late.’ And then we’d pull out the red wine and put on a Sinatra album. But Burton liked Edith Head and he certainly respected her.”

The opposite happened when Head was assigned to design Airport ’77 (1977), dressing all the stars, including Olivia de Havilland and Brenda Vaccaro. Costar Lee Grant had seen Miller’s costumes for a previous film and requested that he design her costumes. The split assignment caused People magazine to report that a rift had developed between Head and Miller. Rather embarrassed, Miller called Grant to let her know about the item. Having studied at the Actor’s Studio and considering herself a serious actress, Grant was not accustomed to seeing her name mentioned in gossip columns. But she squealed with delight, “It’s a starlet item! At last! I love it!” she said.

Stella Stevens in The Poseidon Adventure.

The Pittsburgh newspapers had kept close tabs on Miller’s career and he frequently gave interviews on all of his Universal projects to columnist George Anderson. Anderson was especially shocked to report in March of 1982 that “the handsome and fit-looking Burton Miller complained of nausea and suddenly dropped over. His death was a shocker to his friends and coworkers who will miss him.” He was only fifty-six.

Burton Miller, producer Jennings Lang, and actress Monica Lewis on the set of Earthquake (1974).

“The night before he died, my husband was in New York,” Monica Lewis said. “Whenever Jennings was in New York, Burton stayed with me and the kids, but that night he had to go home. He kissed me good night. He went home and the next morning, I get a call from our mutual doctor, telling me that Burt had an aneurysm and was dead. He was on the floor with a telephone in his hand. The clot had been in his leg, but it went to his heart. It was a shock.”

Miller’s body was sent back to Pittsburgh at the request of his mother. Actor Robert Wagner, whom Miller had costumed in It Takes a Thief (1968), paid for a memorial service in Los Angeles. “Burt was a staunch friend, loyal, no bullshit, funny,” remembered Lewis. “He loved music and art. I could talk to him for hours. He was like a brother. He was a joiner. If we had a piano player at a party, which was often, he would sing all night. He knew every song.”

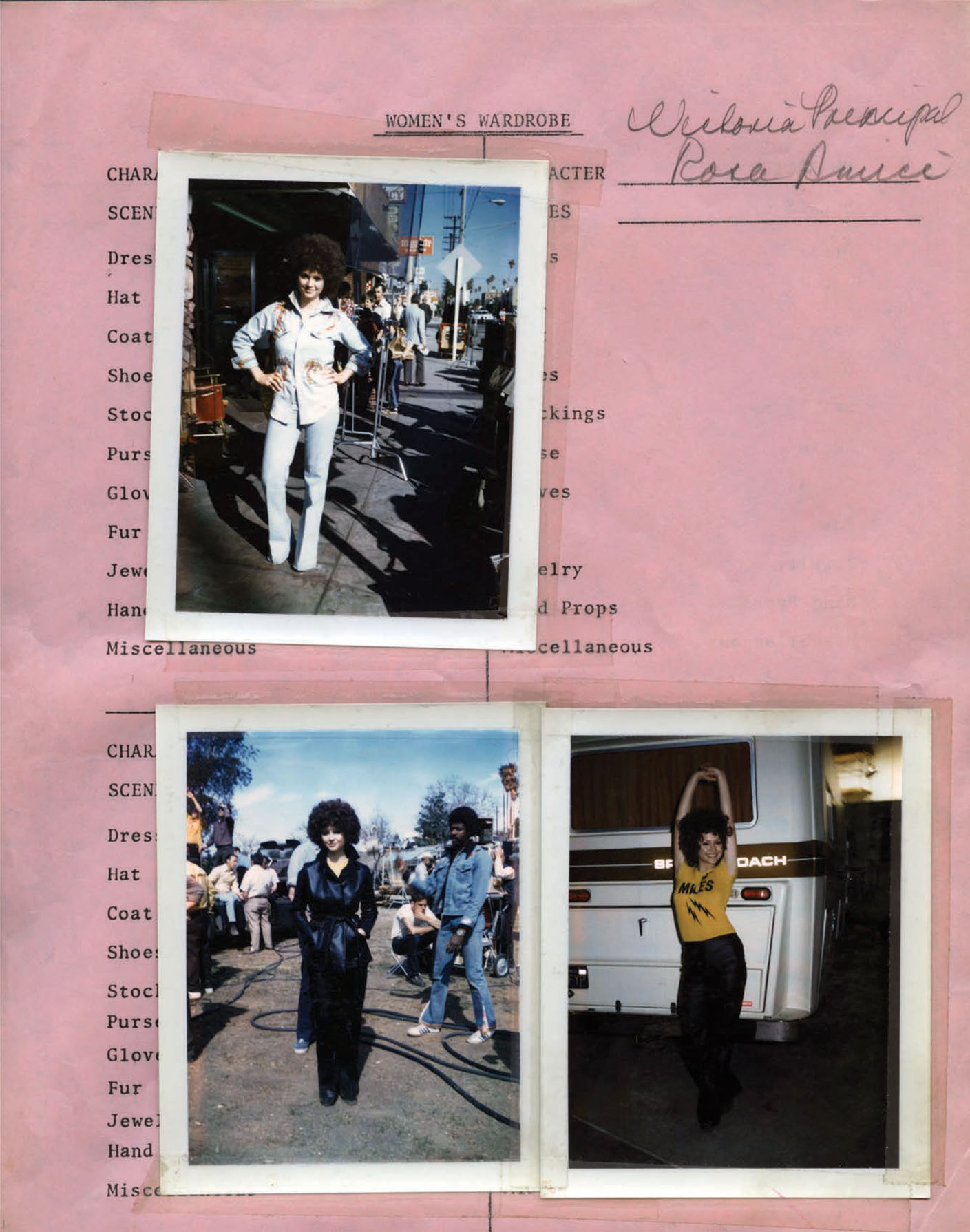

Burton Miller designs for Victoria Principal in Earthquake.