Q: When did you first become aware of fashion?

A: When I was five years old, I would go and shop for my mother. I think there was an element of dress-up that I always liked. Halloween was a big deal for me, even when I was very small. There was the doctor get-up, a cowboy, and an Easter outfit when I was about four with a vest that my grandmother made, and a watch chain and little fedora. At six or seven, during the British Invasion, I had a Carnaby Street cap with brushed denim shirt and shorts, and I would talk in a cockney accent. I guess I always liked the idea that clothes make a character. On TV, there were variety shows like The Carol Burnett Show (1967–78) and The Sonny and Cher Show (1976–77) that had sparkly costumes. The witty, showy, and glamorous things that Bob Mackie designed on both shows had an influence on me. I still love things that sparkle. You’ll see that in The Artist (2011). Part of it was technical because in black and white, it read better.

Q: How did you meet your mentor, Richard Hornung, and can you tell me what you learned from him?

A: I knew him from the 1980s, when I worked as a shopper at Barbara Matera Ltd., and he was assisting Santo Loquasto, Patricia Zipprodt, and any number of other people. He needed someone to size clothes for a week. I was just going in as another assistant, but I was very ambitious and tried to go that extra mile for them. Later, Richard asked me to come out to Los Angeles to assist him on The Grifters (1990).

Richard hired me again to assist him on Barton Fink (1991) for the Coen Brothers. He had already done Raising Arizona (1987) and Miller’s Crossing (1990) for them. I think the Coens are very visual, but I don’t know how costume-savvy they were in those early years. Richard brought so much to the table. He delighted in menswear and had a huge vintage necktie collection. So for something like Barton Fink, he knew how to carve out a character in the language of menswear. John Mahoney’s character, based on William Faulkner, succumbed to the style of Hollywood, so he would be a little snappier but still a Southern gentleman. Richard’s idea was that the first time we meet that character, Barton hears barfing in a bathroom, and the guy had been kneeling on a handkerchief in the stall. All those little details like the two-tone shoes and the Panama hat really flesh out a character. Richard could explain all this to the Coens, and he knew how to talk to actors.

I was happy to be working on something kind of quirky and interesting. It had the same kind of trajectory as The Artist, an independent film made on a shoestring budget, and you’re not sure who is going to like it, but it debuts at Cannes and everybody raves about it. Richard got an Oscar nomination for it. For such a short career, it was a gift that he was able to get a nomination before he passed away.

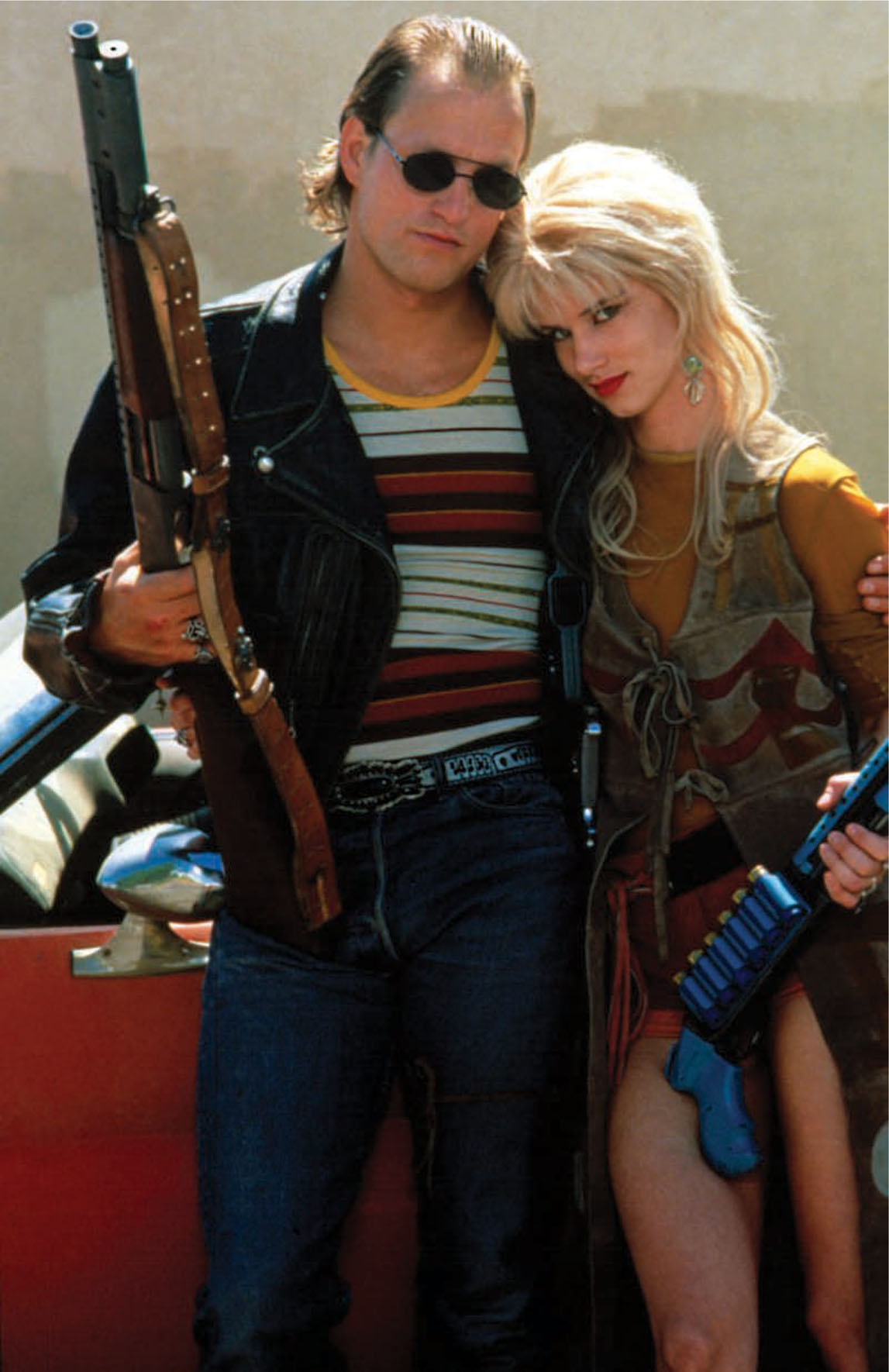

Natural Born Killers (1994) was Richard having free reign. Oliver Stone gave him so much latitude and was like, “Dazzle me. Do what you think is right.” We prepped the show in L.A., but we shot in New Mexico and Arizona. We went to a place down in South Central that had a lot of back stock—1970s underwear, socks, belts, mesh shirts. Richard bought hip-hugger jeans for Juliette Lewis. Now this was 1993, and if you look at jeans from that period, they’re really at the waist. So for her to wear hip-huggers was really retro, and we slimmed them out because they were supposed to be bell-bottoms. People have been wearing them for the last twenty years and I can’t help but think that somewhere there is a grain of Natural Born Killers influencing that look. It was sexy, but it didn’t seem ’70s, and I think Richard was really cutting edge on that.

Q: What is it like working with director David O. Russell on films like I Heart Huckabees (2004) and The Fighter (2010)?

A: With David, I sketch it all in, and he will ask for things. He is very creative on the spot. It can be stressful, especially if we are on location. For Silver Linings Playbook (2012), when you go to a place like Philadelphia, there aren’t seamstresses hanging around waiting for work. For Jennifer Lawrence’s dance costume we had to work around the schedule of the woman who was the cutter for the local opera. We were in a town that is not accustomed to movie deadlines, combined with David’s impromptu creativity. We lucked out because the movie came out well and it looked good. No one would ever see that it was fraught with complications.

Q: You said earlier that you were ambitious. Yet The Artist, which brought you so much acclaim and an Academy Award must have just looked liked another small independent film from the outset.

Jean Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo in The Artist (2011). Costume design by Mark Bridges.

A: Maybe the word “ambitious” doesn’t apply to The Artist. It appealed to me more on an artistic level. I choose things now because I love them. Because I was a kid who grew up loving movies, I was going to do that film no matter what. The crew asked [director] Michel Hazanavicius, “How are we going to see this when it’s finished?” We thought the movie was just going to go back to France and end up on DVD on a shelf in some store.

It was something that nobody else was doing. In this age of CGI and 3-D, we just keep getting more entrenched in computer-generated stuff, which is beautiful to look at, but rather soulless. I felt like maybe we need to go back to simple storytelling. Let’s start over. The first way to start over would be to go to a silent, black-and-white film. You tell a story and then get the CGI in perspective. And look what happened, people fell in love with The Artist and pooh-poohed John Carter (2012), which was all computer.

As a designer, you’re constantly looking for things that will pull your string. It was a challenge to do that movie on such a shoestring budget, but luckily I have good relationships with the vendors in town. I respect their property and they respect my work. Also, I love the thrift store, so I felt I could do it. Was I lucky to get it? Yes. Opportunity met preparedness.

Q: You’ve worked with Mark Wahlberg four times—Boogie Nights (1997), The Italian Job (2003), I Heart Huckabees (2004), and The Fighter (2010). What is he like to work with?

A: I have had the benefit of working with him from the early days. He was very open and he was game for all those high-waisted tight pants in Boogie Nights. Some actors don’t like to sit in a chair and have their tattoos covered up with makeup, so they just want something with long sleeves. I needed to mix it up enough that at some point he needed to wear a tank-top, because it was the 1970s. On the night of the premiere, he came up to me afterward and said, “I didn’t understand at the time, but I understand now what you were doing.” He was smart enough to let me do what I wanted, and then see the final product and appreciate that I was only acting in his best interest and in the best interest of the film.

I have often thought about what makes a costume work for an actor. You’ll get an actor to approve a costume if they look good, but it makes them feel like somebody else. It’s an elusive combination. I don’t think anybody goes into a fitting saying, “Make me look horrible” unless you want to do The Elephant Man or something. They know they’re going to be forty feet tall on the screen and they’re worried about the size of their ass, no matter how famous an actor they are. There is probably more to it, but those seem to be the two special traits.

Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis in Natural Born Killers (1994). Costume design by Richard Hornung.