Q: You were a travel agent up until the time that you were about thirty. How did you move into costume design?

A: I was always interested in design, but not so much in costumes as in fashion. When I was going to college, over a couple summers I went to fashion houses. But I got so turned off by the whole process and by fashion itself, it kind of set me back and I just forgot about it. When I got out of the Army, I was kind of footloose and I didn’t know what I wanted to do. My father had a very successful travel agency and that’s why I became a travel agent. It was good for both of us, and we got to know each other. He loved what he was doing, but I felt like I couldn’t spend the rest of my life there. Then one day, all of a sudden it came to me. I thought, “I don’t like fashion, but I like theater and costumes.”

A friend suggested I contact Helene Pons, who was a designer and also executed costumes for other designers. Three days later, I got a call from the friend who said that he had dinner with Helene the previous evening. She needed to go to Rome, but she couldn’t get any space on a flight. I called her and she gave me the dates, and I found space for her. When I called her back she said, “I understand you want to speak to me.” I told her I thought it could wait, but she said, “No, it can’t wait, come right over.” I was just going for some advice, but Helene was about to begin working on the Broadway production of Camelot (1960) and she offered me a job. I left the travel business that Friday and started with her on the following Monday.

When I first started, I was just thrown into it. I was so busy learning everything I had to learn, I didn’t think about why she hired me. Only later did I realize that she understood that I had been running an office of about thirty people and she needed a manager. The product varied, but the skills of running an office were the same. Helene had one major flaw: she would go to any length to save on fabric. I knew after a couple months, you don’t save on fabric, you save on manufacturing. You save on the time you spend making something. But I learned a great deal from her.

Q: How did your film work begin?

A: I met the designer Theoni Aldredge when I was assisting her on the production of Ilya Darling (1967). Theoni called me about working on a movie. I felt that I still didn’t know enough about movies, and I was still working on a musical, so I turned her down. Weeks later, just as we were about to open for the out-of-town tryouts, they let all the assistants go. Theoni called again about the movie. I asked, “When do you need me?” She said, “Immediately.” I said, “What is it you want me to assist you on?” She said, “I don’t want you to assist me, I’m trying to get you this movie.” I was dying. I met with the producers immediately and got the job on The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1968). Alan Arkin, who was in that film, recommended me later for Popi (1969).

Q: What were your experiences like working with director Bob Fosse?

A: Lenny (1974) was a period piece at the point that we made it, a film made in the 1970s, taking place in the 1950s. I tried to dress Dustin Hoffman as Lenny Bruce, but it didn’t look right. What worked on Lenny Bruce were tight little suits, shirts, and ties. So little by little, I went away from that. There were elements I used. But it was an awakening that even though I was using a real person, who had died not that much earlier, I had to change it. There was one thing that Bob had in mind: having one of the nightclub routines being done in a raincoat. I don’t remember seeing that in my research—that was something in Fosse’s mind.

On All That Jazz (1979), we started production three months before shooting with Richard Dreyfuss. He was a wonderful actor, but he just wasn’t right, and both Fosse and Dreyfuss knew it. So we closed down for a while, and they cast Roy Scheider. My job was to make Scheider look as much like Bob Fosse as possible to the point where we were testing the night before shooting, and his beard was so black, he looked like Othello. I recommended they bleach his hair, and he finally really looked like an essence of Bob Fosse. When I start with a real authentic figure, like a movie star, I start with total reality. But these are not documentaries, so you always have to find that middle ground. Fosse always wore black. It was a uniform. He wasn’t trying to make a statement. That was what he was comfortable with, and he didn’t have to think about what to wear in the morning. Fosse was never dogmatic about costumes. He would have some ideas and if he didn’t like it, you would find out. But, otherwise, I was pretty free.

Roy Scheider in All That Jazz (1979).

With most directors, you don’t ask, “What do you want the character to wear?” I don’t want to hear that anyway. I just want to hear about the essence of the character, I want to know why they’re making the movie and what they think it’s about. Then I want to come up with things and then we can talk about if it works or not. The beauty of when you work with someone a lot is that you can finish sentences for each other. Where Bob was wonderful was not telling you what to do, but he could see immediately if something was right or wrong, and he knew why.

Q: When you designed for Meryl Streep in Still of the Night (1982), was she comfortable being so glamorous? She seems like she is not as conscious about clothes in her personal life as she is about dressing her characters.

A: That’s absolutely true. Off-camera, she couldn’t care less. She’s a very modest dresser. It’s not her thing. Maybe now it is; I haven’t worked with her in some years. But when it came to the character, clothes were very important to her. She works like English actors do. They have to know what they’re going to look like before they can develop their character. Laurence Olivier was like that. He really was concerned about the external look before he could do the internal part of the acting. When Meryl looked in the mirror during a fitting, she was looking for the character.

With a character like Sophie in Sophie’s Choice (1982), I asked, “Where has she been? Where is she going? Financially, how did she afford her clothes?” She was a refugee and she lived in Brooklyn. Those are things that needn’t be spelled out on the screen, but that’s what you use to get to a look.

Q: As Sophie became more fragile, did her clothes become more fragile? Kind of like Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire?

A: I think she was someone who, no matter what she wore, didn’t know she was wearing it. Her entrance was very important to me, when Stingo (Peter MacNicol) sees her for the first time, it was the middle of the afternoon. I had her come down the stairs in a slip and a peignoir to look like she just had sex. She liked the idea too because it sets up a “before.” That’s what clothes should do. Our job is to really tell a story and help the script as much as possible.

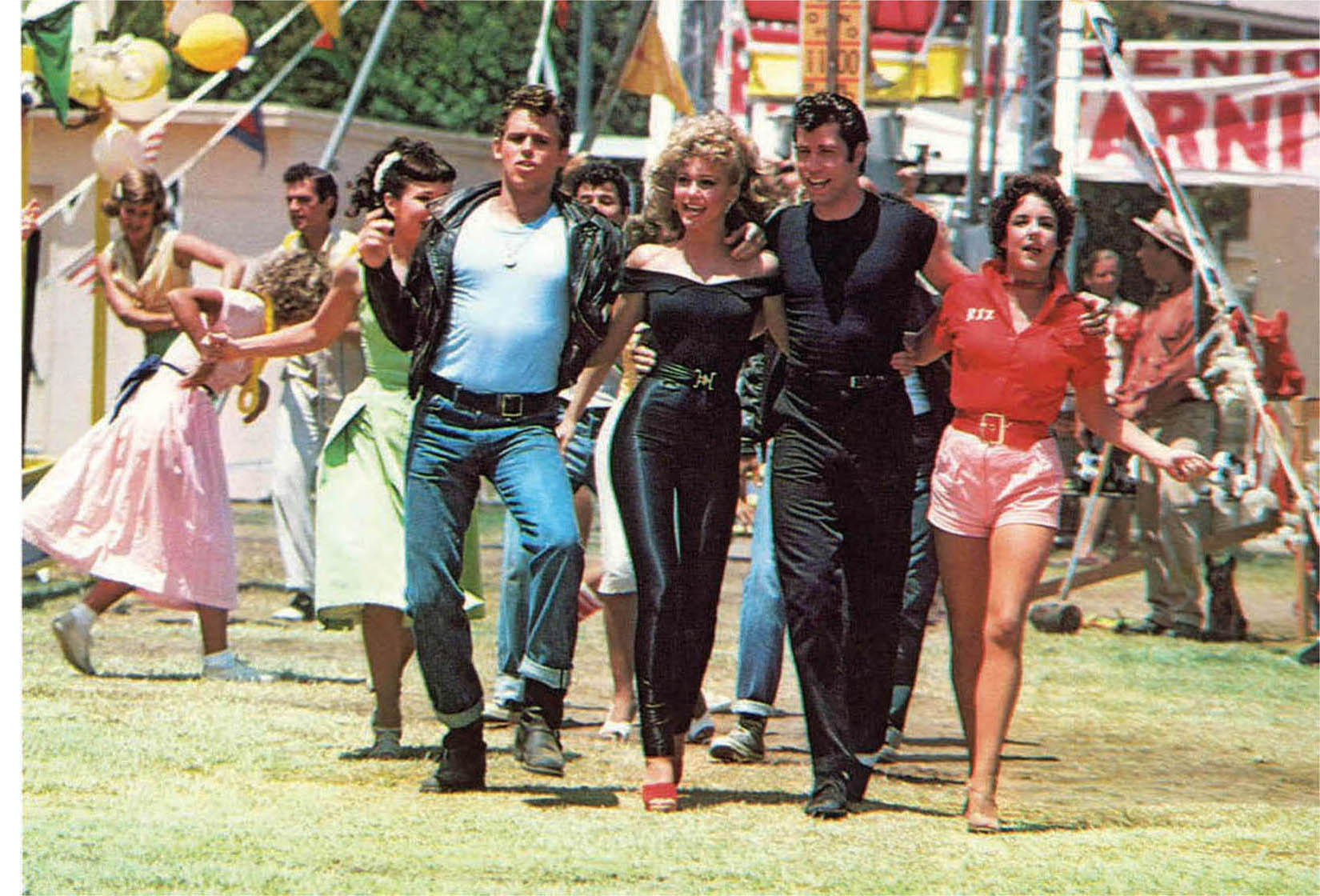

Jeff Conaway, Olivia Newton-John, John Travolta, and Stockard Channing in Grease (1978).

Q: Your beaded gown for Annette Bening in Bugsy (1991) was really a showstopper.

A: Film ratio changed and in most movies, they don’t shoot costumes full-length, which I need to establish a period. I asked Allen Daviau, the cinematographer, “Am I ever going to see a full-length shot?” A couple days went by, and he said, “I have a gift for you.” And it was a full-length shot of Annette’s entrance in the beaded gown to Bugsy Siegel’s house. He backlit her, so you could see right through the dress, and you could see her legs moving through the beads. It was totally unexpected and it was a gift.

Q: What was it like working with a blonde Barbra Streisand on All Night Long (1981)?

A: In those days, a lot of movies were being done by costumers and not costume designers. It was only later, little by little that it changed. Mostly it was the designers’ fault. In the Golden Age, you saw in a film’s credit “Gowns by” or “Designed by.” They did the stars, but no one else. So the wardrobe department, more and more, took over. When I got in, I had to fight to be in control of the background actors, especially on Grease (1978). Even if I don’t actually do it myself, I don’t let anything go by without checking it.

All Night Long started out without Streisand. She was brought in to replace another actress. Then they needed a designer, so I was brought in. Barbra likes to be totally in control. She’s opinionated. There’s some street stuff about her, which I liked very much, and I responded to her. Even when she drove me crazy, I still liked her.

Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice (1982).

Q: But it’s a positive thing when an actor cares so much about their character, isn’t it?

A: Caring about your character is important. An actor looking in a mirror and giving no reaction is death to me. There’s a difference between caring and controlling. You almost get the feeling that something has to come from them, or else it isn’t important. Not necessarily with Barbra, but you could suggest something to an actor on a Monday and they don’t like the idea. But on Wednesday they come to you with the same thing, and now it’s their idea.

Q: Did you expect Grease to be such a big hit?

A: Grease was a very popular show on Broadway, but it was a mess. What I didn’t realize until later, and I think the reason the movie was so popular, was we made a messy movie. None of us knew what we were doing. I did a show-and-tell for producer Allan Carr and he told me my concept was too real. He told me I needed more color and to punch it up, and he was absolutely right. So I went back and I started using colors I’d never used before, or since. But I really credit that critique with giving me the edge of what I had to do because I couldn’t figure out how to translate that stage material to the screen. You couldn’t be realistic. Our actors that were playing high-school seniors, were dying out their gray roots. It was the kind of project that shouldn’t have worked. All the creative people had their own problems they needed to work out with no guidance at all, except for Carr’s mantra to make it colorful. We had to really push it, and make it almost surreal.

Olivia’s last costume was based on drawings from Frederick’s of Hollywood catalogs. She couldn’t wait to get into it after wearing all these goody-goody clothes. She was sewn into it because there were no zippers. That tight black clothing was worn by, well, nice ladies didn’t wear them.

Annette Bening and Warren Beatty in Bugsy (1991).

Costume designer Helen Colvig (left) fits skater Carol Cooper for ice Follies (1968).