Q: How did you first become interested in design?

A: When I was five years old, I put my foot through a window, which caused me not to be able to walk. While I was bedridden, my mother bought fashion magazines for me. I would cut out figures from the magazines and then design makeshift paper clothes to put on them. I also developed a love for fabrics. Around the corner from my home was a dry cleaner that did pleating, and they would throw scraps of fabric away, which I would retrieve from their trash cans in the alley. I kept my treasures in a cigar box, and my dreams grew of becoming a costume designer. I carved a small dressmaking form for which I would make clothes.

Q: Where did you study?

A: At Chouinard Art Institute, and then I continued my studies at Otis Art Institute, studying sculpture. I married and had a son. With only some amateur dance work under my belt, I applied for a job at NBC, working in the costume department for live television. Knowing how to sew was a tremendous asset, and I worked as a costumer dressing performers in musicals and on The Dinah Shore Show. You had to work very fast, and this was in the days before Velcro. We used what we called “pie pans,” which were the biggest snaps you could buy. I moved to CBS, dyeing shoes, assembling costumes, and assisting performers with their quick changes, often working in teams with other costumers. I thought I was going to have a heart attack sometimes.

Q: How did you make the transition to films?

A: I had gone to Disney to costume the Mouseketeers for The Mickey Mouse Club. In 1955, the Screen Actors Guild declared a strike. When everything got settled, all of a sudden everybody was busy, and they soaked up every bit of talent. There were no costumers left. Adele Palmer of Republic Pictures called my boss looking for a costumer for Patricia Medina for Stranger at My Door (1956). It was a chance to be an on-set costumer, instead of working in stock, so I seized the opportunity.

Q: How did you begin your association with Alfred Hitchcock?

A: I saw a Hitchcock show on TV one night, and I thought “Gee, those costumes look so real.” They didn’t look like costumes at all. I don’t know what prompted me, but I called Revue Studios, which was on the Republic lot, and asked to speak to the costume department. A man answered and I said, “I don’t know who did the costumes on Hitchcock last night, but I just wanted to tell you and your department that it was so convincing and so good.” He asked me who I was and I told him that I had worked for Adele Palmer. Though I wasn’t actively looking for work, the man took my name and number in case he had a need for a woman costumer. The next day he called with a job offer. “Do you know what a Merry Widow is?” he asked me, “Well, Fay Wray wants one and I don’t know what it is.” I knew what it was, so he hired me as a costumer. After I completed an assignment to dress a ventriloquist’s dummy for Claude Rains to use on Alfred Hitchcock’s TV show, Revue began using me more as a designer than a costumer. Then MCA, owner of Revue Studios, acquired Universal and the staff moved to the Universal lot.

Q: How did Hitchcock use costumes to convey character in Psycho?

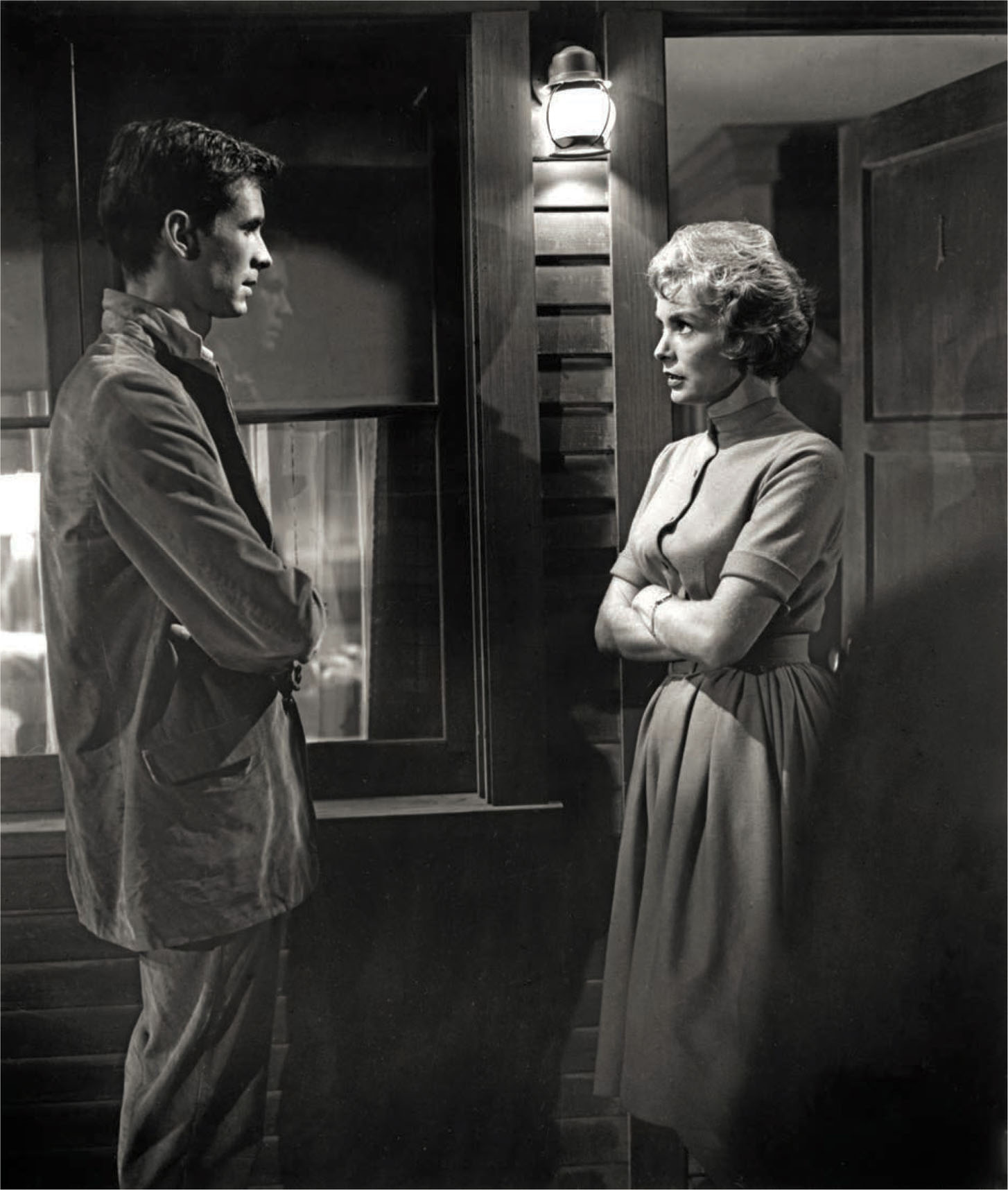

A: We didn’t make clothes for Psycho because he wanted Marion (Janet Leigh) to wear what she could have afforded in real life. It was all off-the-rack. Hitchcock had an authentic real estate office photographed in Arizona. Then he went home with the employees and photographed their clothing in their closets. He showed us the photographs and said, “This is how I want my principals to look.” In the beginning of the film, Janet Leigh wears a white bra and slip. But after she steals the money from her employer, Hitchcock wanted her in a black bra to show how she has fallen.

Q: What was it like working with Clint Eastwood when he directed Play Misty for Me (1971)?

A: Clint wanted Jessica Walter’s character to look like a normal person, but she was a nut. Hitchock used to use the term “McGuffin,” and that was a trickery—the thing that you didn’t think was going to happen. You never suspect that person because they look so normal. But slowly, the characters got nuts or became murderers. Just like Tony Perkins wearing sweaters in Psycho—he looked like a nice, relaxed guy. But then when you start seeing the stuffed birds, you start saying, “uh, oh.” The costumes were never to give anything away, but slowly the action and the story will explain what happens. The clothes had little to do with it.

Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh in Psycho (1960).

Q: Was Marlon Brando a “method” actor about his costumes in The Appaloosa (1966)?

A: He is a tough man to work for. He provokes people. He put me through the wringer. He wanted this, he wanted that, and it wasn’t right. I told him, “You’re a peasant, you know. Mexicans don’t wear royal blue.” He said, “That’s what I want.” I told my boss, and he said “Make it.” So I made this horrible blue outfit and Marlon looked at it, and I said, “You’re not even going to put it on, are you? I told you that we were going to do these white peasant outfits, but you didn’t accept it. You wanted this one.” And he said, “Well, I don’t want it. I want the white outfit.” Here we spent so much money on a whim of his, but he was just provoking. I made a serape for him, and it had color threads running through it. During production, he would sit on his horse with it on and he pulled all the color threads out of it. He’s a fair guy, but when there’s not enough amusement, he’ll aggravate you.

Gene Wilder and the Oompa Loompas in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971).

Q: Was working on Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971) a kind of crazy experience, like the film itself?

A: I read the book and the script, and knew it was a fantasy. I talked to the producer and I met with Roald Dahl and they wanted to see what I was going to come up with. I made up the sketches, and they approved them. They didn’t shoot the film in Los Angeles. It was shot in Germany because they got a tax break. All the clothes were made abroad from my sketches. I never saw any of the costumes until they were on the screen. It disappointed me terribly because I really wanted to supervise. I had worked on pictures before with [director] Mel Stuart, and he was such a difficult man. I learned on I Love My Wife (1970) that he was a screamer, and when he was displeased, he would just scream you down. When people start screaming, your first thought is that they must be so insecure to just blow up like that.

I didn’t know how we were going to engineer Violet’s expanding suit in Willy Wonka, and still to this day, I don’t know how they did it. Mel didn’t know what he was doing with the Oompa Loompas. They were supposed to look like candy. But he didn’t want them to look like they were made out of chocolate because he didn’t want them to look like they were in blackface. So he made them orange. What a crappy color. It could have been lavender. It could have been anything—pink, like a piece of candy. I hated it. He had me make sketch after sketch because he said, “It has to look like they’re wearing candy,” but it didn’t come out that way. He was thinking of candy that he knew as a kid. But I didn’t know that kind of candy because he was from New York and I was from California, and we had different kinds of candy.