Q: When did you first consider costume design as a profession?

A: I was living in Chicago and working with an artists’ collective. We were making one-of-a-kind clothing and having little art shows in eclectic places. That led to my being asked to have some of my clothes sold at local boutiques in Chicago. At that time, I was making jackets out of fabrics that were older and damaged. I would cut around the damaged parts and make something new out of something old. There was a movie filming in town and an actress bought one of my jackets and brought it to the set because the sleeves were too long. They made some inquiries because they thought it was unusual, and I was invited to the set. Theoni Aldredge was the costume designer on the film, and she asked me if I ever thought of becoming a costume designer. I said I hadn’t thought of it, but the question seemed to resonate with me. I had been to art school at CalArts, I’d been to theater school at UCLA, and I’d been sewing since I was twelve years old. I told her I thought it was a fabulous idea. She suggested I work my way into the union as a seamstress and work my way up to costume designer, and that’s what I did.

Q: So you had already studied in Los Angeles, but costume design hadn’t entered your mind?

A: I had asked my mom for a sewing machine when I was twelve, and she couldn’t figure that out. I just had this burning desire, but I never put the pieces together. It’s funny how your life is just sitting there waiting for you to recognize it, and somebody else tips you off to what’s going to happen in your life.

Q: How did your first film happen?

A: When I came back to Los Angeles to pursue this new career, one of the friends I had made while I was living here before said, “Oh, I’m producing a movie! Let me give you a job as a seamstress!” It was just sort of odd. All the pieces start to fit together when you’re on the right path. In my life, I have chosen to go forward on my instinct—something pushes me forward. Then I find myself in a situation that seems practically impossible and I have to tackle the unknown.

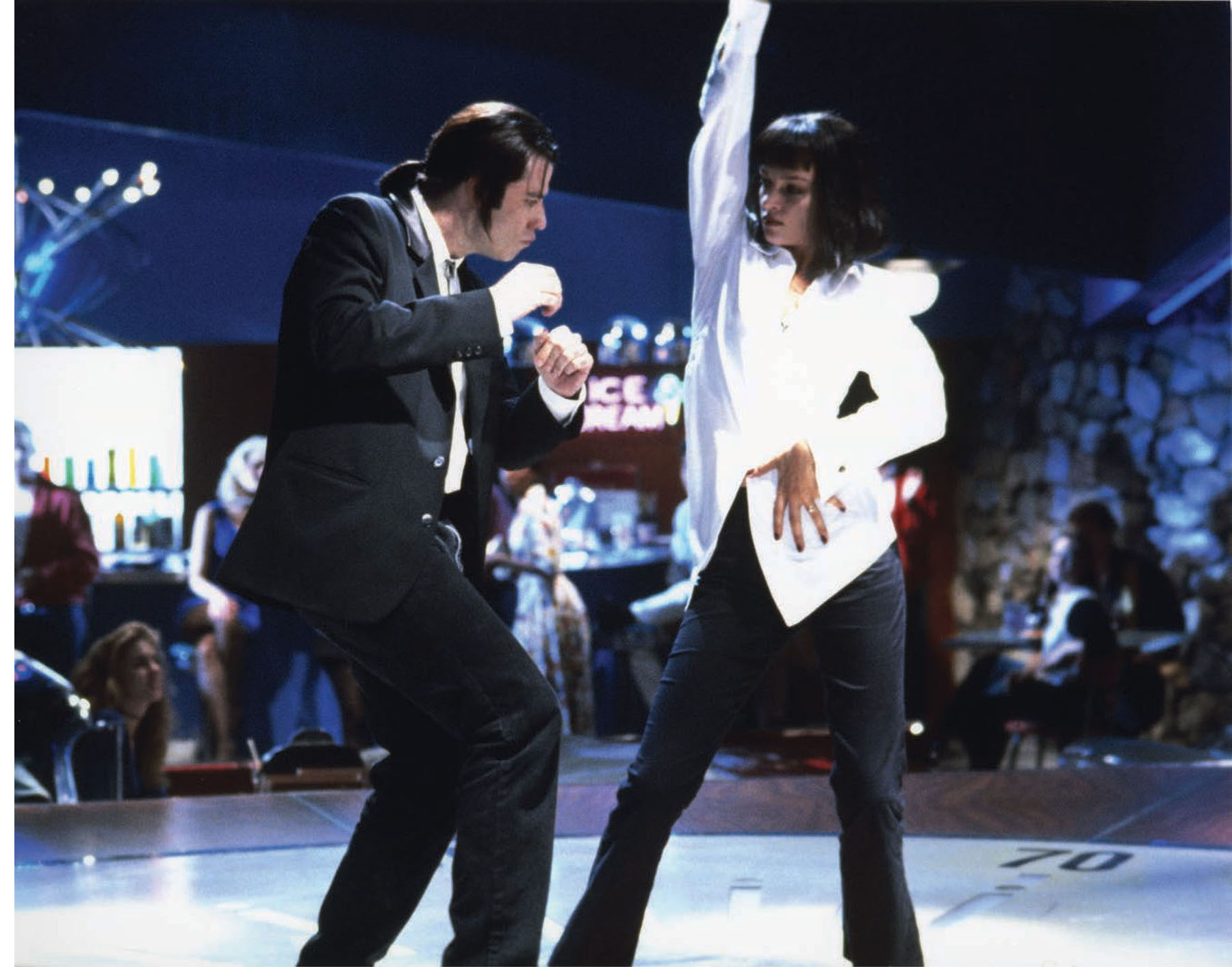

Q: When you approach an article of clothing that seems simple, say, Uma Thurman’s white shirt in Pulp Fiction (1994), what do you factor in when making the decision to design it yourself or purchase it?

A: Sometimes what you want isn’t out there, even if it’s as simple as a white shirt. Maybe nobody is making a white shirt that is depressed at the waist. For Renée Zellweger in Jerry Maguire (1996), I had to find a black dress that tied at the shoulder so it could fall down and create a sexy moment onscreen. The line in the film was “That’s not a dress. That’s an Audrey Hepburn movie.” There was the dress that Audrey Hepburn wore in Sabrina (1954) and my dress was an homage to that dress. There is a moment in the film where they are on the steps and he has to untie the dress. It’s a cinematic moment written in the script. I could spend my life wandering around the universe looking for a dress that will do what’s written in the script, or I can design one. If I want a jade-green blouse and that’s not the color of the season, I make one. Now, I am a very good designer and I don’t need to prove that every time. So I design the clothes that need to be designed to move the story forward and meet the needs of the director and the screenplay.

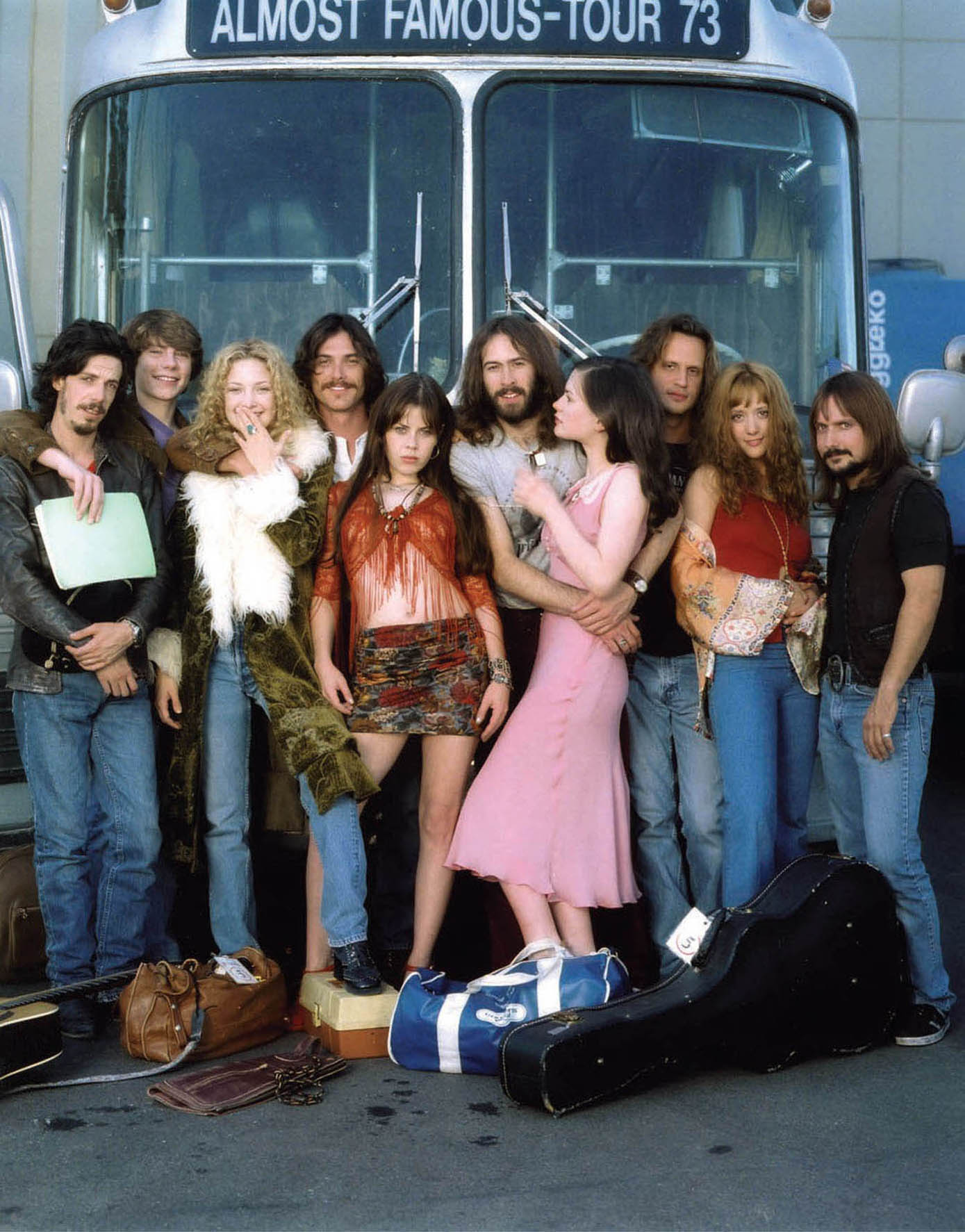

On Almost Famous (2000), I did such a good job of aging everything that people thought I got everything from a thrift store. When, in fact, every single thing in that movie, except for the blue jeans, was designed in my workroom—every T-shirt, every logo, every blouse. For the jeans, I went up to Seattle and dug through barrels of clothing like a mad woman to find the period blue jeans. Because of the way we treated the new clothes, the movie was overlooked for costumes, because people thought they came from a thrift store. It’s a very high compliment, but it shows a lack of understanding for what we do.

Q: You helped to bring back the narrow silhouette in men’s suits with Reservoir Dogs (1992).

A: [Director] Quentin Tarantino wanted to evoke the French New Wave films. He also wanted the characters to have a certain anonymity. With a $10,000 budget for costumes, I couldn’t afford to buy new suits and all the multiples we would need. These guys had all just gotten out of prison, so I figured they probably bought their suits at a thrift store. Quentin’s suit came from a warehouse downtown because he didn’t need multiples, but for Tim Roth and Steve Buscemi, I needed four suits for each of them. So I found a place that had old stock 1960s dark jackets.

Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Q: I understand you were instrumental in helping Paul Reubens’s career along.

A: After seeing Paul do ten minutes of Pee-Wee Herman, I literally saw dollar signs jumping all around his head—like little cartoon dollar signs—it was kind of strange. We waited after the show to see him, and I said to him, “You are going to be very rich one day.” He said, “Well, thank you very much, I wish I could believe it. I have my own show that I am trying to do. I sent a few people to see him, but they didn’t appreciate him.” He said to me, “Why don’t you produce my show? You understand it and have a passion for it.” This was during an actor’s strike and there was no work for me at that time, so I said I would do it.

Paul knew a woman who would do the publicity for the show and he borrowed $8,000 from his parents. We opened at The Groundlings, and we became popular. I felt like we needed a bigger venue, so I went over to the Roxy on Sunset Boulevard. I waded through all the smoke and met Lou Adler. He said, “What do you want, kid?” I told him about the show, and he said, “No way, we don’t want your show.” So I asked what night was the worst for his business, and he said it was Tuesday night. So I suggested he just let us try the show on Tuesday nights. We ended up getting a few nights at the Roxy, and Marty Callner from HBO saw the show, and I sold it to them. We made a lot more than $8,000.

John Travolta and Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction (1994).

It was another one of those things like “How about being a costume designer?” I just did it and it was hard, but I was knee-deep in it. I paid everyone a salary from the money we took in, and it turned out great. The interesting thing is the difference in perception. We were quite the rage and after the show, people would come to talk to me and if they would ask, I would tell them that I was really a costume designer. “But you’re the producer now,” they would say. But I viewed it as a temporary job. I had told Paul, “All I want is for you to be famous and to send me a check every now and then.” And that’s exactly what happened. When I told people I was going back to being a costume designer, they would look at me like I was the stupidest person they ever met or I was no longer of interest to them. It was curious.

Almost Famous (2000)

Johnny Depp as Edward Scissorhands (1990).