When I began collecting Hollywood costume sketches in 1992, little information was available on the costume designers. Auction companies set their prices almost entirely on the star depicted, with little thought given to the creator of the sketch. I always thought it inequitable that the careers of fashion designers spawned a large number of articles, books, and sometimes even movies; yet the lives of costume designers—whose work so influenced those fashion designers—remained largely undocumented. Living in Los Angeles, whenever I met someone who worked in the costume design field, I pestered them with questions about their work and the history of the industry.

I had always hoped that my friend David Chierichetti would one day write the book I wanted to read. David had written Hollywood Costume Design in 1976, which was the first overview of design in films. David had known many of the designers of Hollywood’s Golden Age at a crucial time—when they were retired and could speak freely of the highs and lows of their careers. Over the years, he told me many of the stories that did not make it into his book. One day while we were having lunch, I asked him when he was going to finally write a book with all of those stories. “I’m never going to write another book,” he said. “That will be up to you.”

So I set out to write the book I always wished existed. Many questions intrigued me. What made a designer seek a career in films? What were their relationships with stars and directors? And often, why did they leave the industry midcareer?

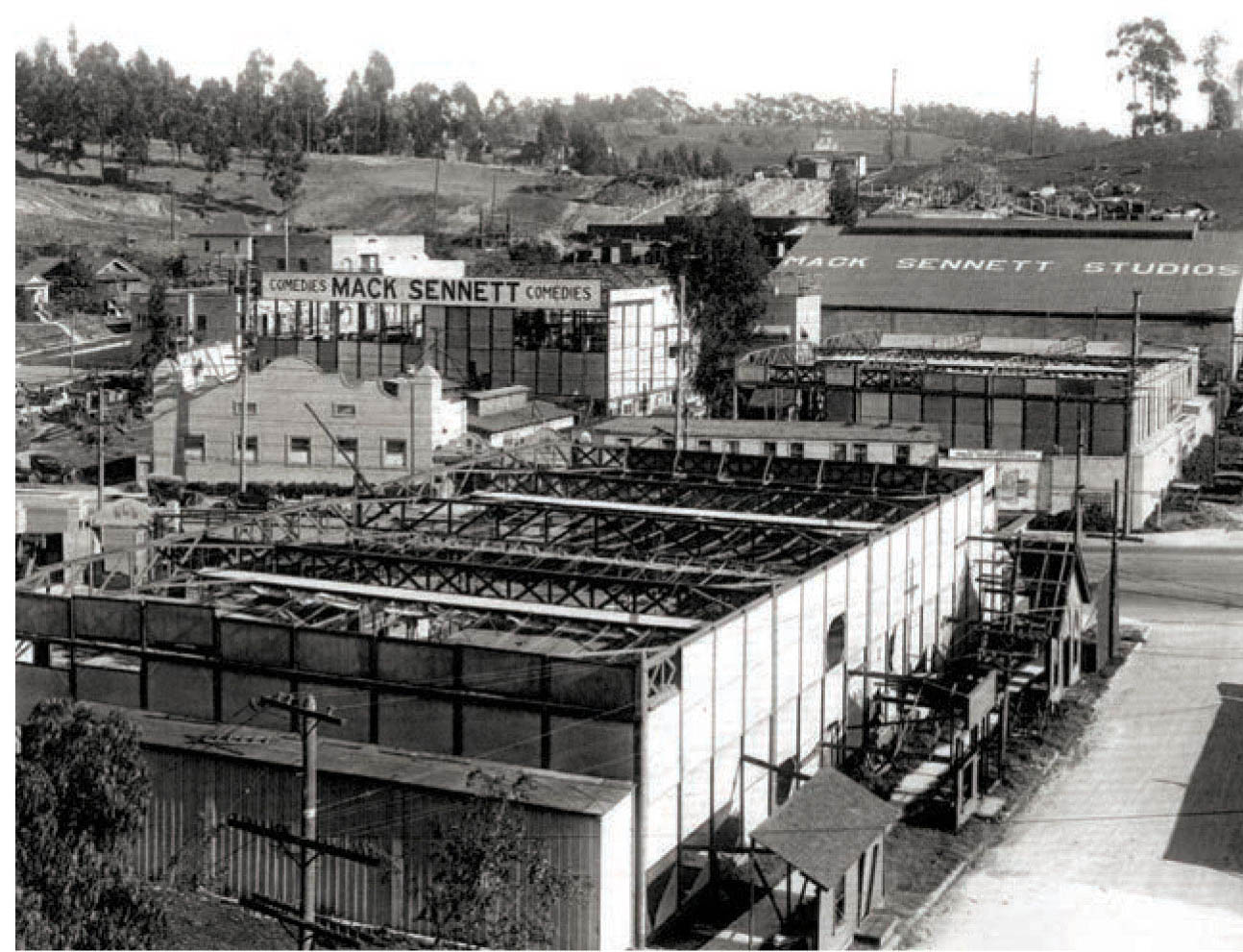

Our story begins in 1909, when Southern California’s ubiquitous sunshine and its distance from motion picture camera inventor Thomas Edison and his patent lawyers enticed producer William Selig to make films in the Edendale neighborhood of Los Angeles. Multiple movie companies soon sprang up within a stretch of several blocks along Allesandro Street, later renamed Glendale Boulevard. These early American producers put little emphasis on costume. “When motion pictures were still too young to talk, it was the privilege of the star to report to a studio garbed in her red dress, or her blue, or her white—just as she preferred,” wrote Talking Screen magazine contributor Dorothea Hawley Cartwright in 1930. “It mattered not the least that she wore the same gown as a Tennessee mountain girl in one picture, and as a society belle in the next.”

Fabled producer D. W. Griffith was among the first filmmakers to realize that relying on the actors’ personal wardrobes often compromised effective storytelling and diminished a film’s overall impact. On The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916), he not only budgeted money to costume his players, but he also hired a designer to create costumes specifically tailored to each production. Both practices would eventually become industry standards, though early producers could not spend as lavishly as Griffith had.

Fittingly, the capital to support this phenomenal growth in wardrobe departments came from entrepreneurs who had done well in the fashion business. Eager to become Hollywood studio moguls, these investors poured their manufacturing profits into the fledgling film industry. The roll call of early studio executives reads like a fine department store’s vendor list. Paramount founder Adolph Zukor had been a furrier in New York. William Fox of 20th Century-Fox fame had been a dress manufacturer. Samuel Goldwyn had worked for a glove company, and Louis B. Mayer of MGM had been an antique and button dealer. Universal’s Carl Laemmle had been a haberdasher. Because of their backgrounds, these men appreciated the value of good clothing. They did not hesitate to turn their movie profits back into their wardrobe departments.

L. L. Burns, a collector of thousands of Native American artifacts, jewelry, weapons and clothing, founded Western Costume in 1912, partially in response to the ridiculous and inauthentic ways that Native Americans were being costumed in films. Indigenous wear was often just a random assemblage of beads, feathers, and furs that bore no resemblance to authentic dress. Burns quickly developed a reputation for supplying historically accurate Western wear and expanded his collection to include other periods.

For the most part, the first wave of designers and costumers hired by the studios came from theatrical backgrounds. Nepotism was also common, as many hires had a son, daughter, or husband already employed by the studio. The mothers of actresses Mildred Harris and Virginia Norden were both hired to costume Thomas Ince’s films. The wife of actor Frank Farrington had begun her costuming career on Broadway before being hired by Thanhouser Company in New Rochelle, New York. But Hollywood was the Wild West, and it attracted a group of talented designers and dressmakers looking to make better lives for themselves at the dawn of the film industry. These are the stories.

In doing my research, I found that frequently studio biographies fudged many details of designers’ lives, and many have come to be accepted as fact and are repeated over and over, particularly on the Internet. Some designers claimed to have worked in or owned fashion salons in Paris or New York, when records show they never even lived in those cities. More often than not, designers’ generally accepted birth dates could vary widely from their official birth records. Census records often gave a very different account of the early years of some designers from what has been known. But even census records needed to be scrutinized. Many female designers, though clearly divorced, often told census takers they were “widowed.” Through intense research, every effort has been made to separate fact from fiction.

Please be advised that you will encounter stories that don’t mince words, nudity, murders, suicides, vamps, and villains. After all . . . it is about the movies.

—JAY JORGENSEN, MARCH 2015

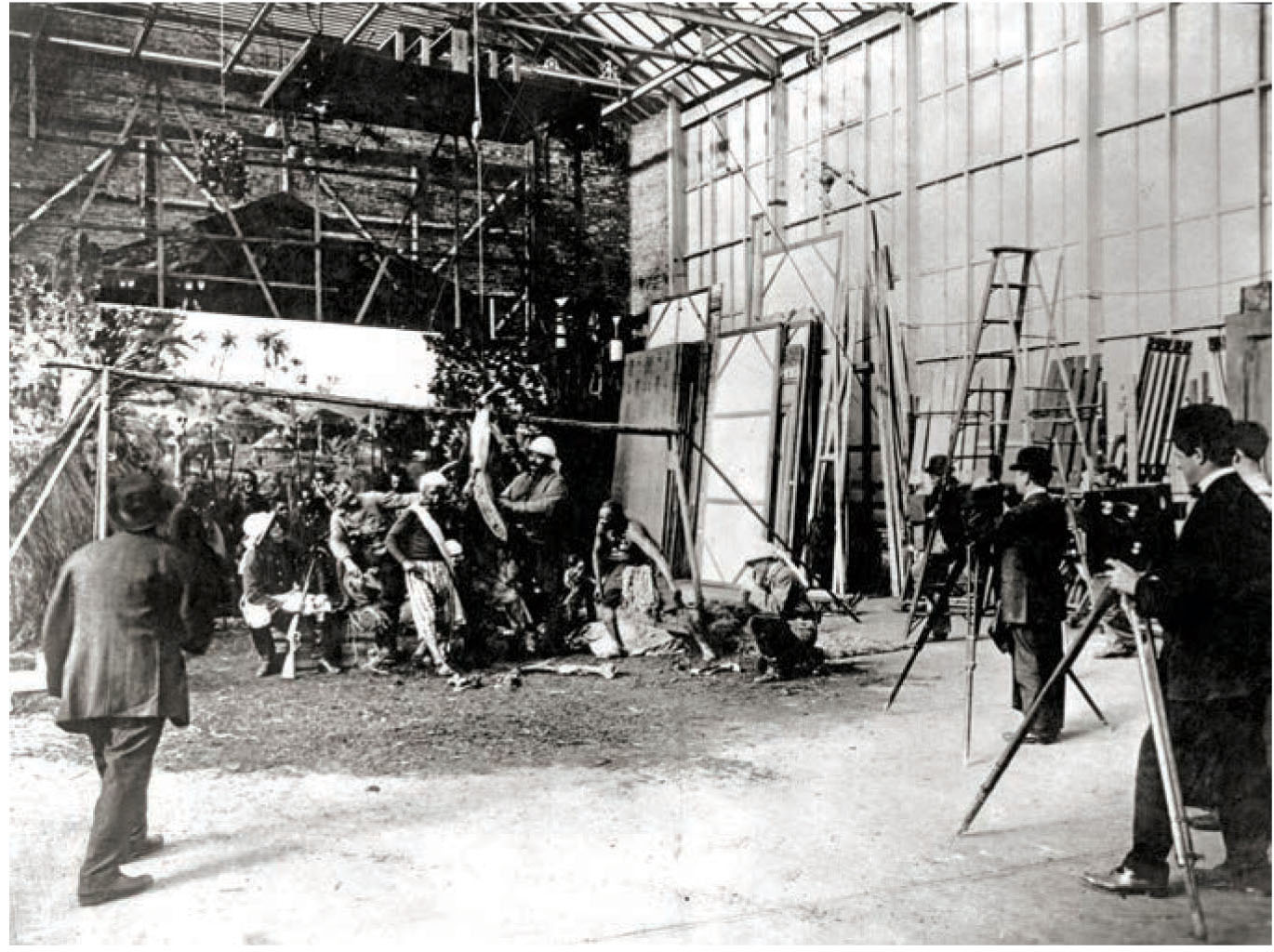

An early silent film set.

Mack Sennett’s studio in the Edendale section of Los Angeles.

On the set of Cleopatra (1917), Theda Bara’s revealing costume stands in stark contrast to the modest clothing worn by wardrobe personnel.