4

The Practical Future

For urban humanities, to imagine spa-tial justice in the city means to under-take historical analysis, contemporary cultural and social interpretation, and speculative thinking. This is a generative practice, in which past and present inform speculations about the future. While the demarcations of disciplines such as history and cultural studies may be productively contested, the disciplinary terrain of the future is decidedly more ambiguous, without a shared theoretical or methodological foundation. The past not only has its own field—history—it also has a piece of many other fields (such as art history, history of philosophy, history of science, and so forth). Similarly, the present is studied in a wide range of fields such as cultural studies, sociology, psychology, and anthropology. The future has no such purchase or reciprocity, although a number of professional fields—from architecture and planning to social welfare and public policy—certainly aim to intervene in the present for the sake of creating a more just, equitable, and better future.

While the disciplines of urban planning and architecture incorporate historical knowledge and social science methodologies, their intrinsically forward-looking perspectives give rise to valid, critical questioning within the humanities. If architecture is, in some sense, always trying to reimagine a better world, it does so through design practices that embed tacit assumptions about the occupants of its plans. Similarly, planning and its subspecialties translate metrics into plans and policy that will inevitably have both intended and unintended consequences for diverse populations. These virtual proclamations about how daily life should unfold produce genuine disciplinary friction, especially among humanists, who interrogate the justification for making such claims, the grounds for the designer's or planner's agency, and most vociferously, the assumptions regarding the users. Who, exactly, are these designs and plans for? As a result, imagining future implications for the city is one of the urban humanities’ most challenging—but potentially most constructive—components, producing explicit terms, positions, and frames for debate. What we call the “generative imperative” signals the importance of experimental, studio-based work that is propositional rather than merely critical, prioritizes interdisciplinarity over specialization, and pursues a project orientation as the avenue to a broader understanding of the urban.

Urban humanities contend that we engage with speculation about the future in a way that can withstand substantive critical inquiry. Yet this perspective of engaging with, designing for, and speculating about the future is so underdeveloped within the humanities that it can be difficult to move from well-articulated debate to rigorous, creative, forward-moving thinking. Perhaps this is because the hallmark of academic work is mainly a critique that often remains within scholarly discourse when, as we argue here, it could be more productive if pushed into the public sphere. This is not to say that there aren't already many compelling examples that link intellectual scholarship with activism. Phi-losopher Angela Davis, for example, not only stands against the prison-industrial complex but imagines a world without prisons;1 sociologist Manuel Castells lends power to his substantive critique of neoliberal urbanism through studies of alternative, cooperative communities;2 writer Octavia Butler builds worlds with alternative forms of humanity, kinship, and social structures—forms that move beyond racial violence and economic stratification.3 These future-oriented projects advance what is currently “unthinkable,” precisely so that it can be thought out.

Widely accepted models of futurity exist even in architecture and planning; theories and methods for speculative thought range from utopianism to participatory planning. Relatively recently, voices from literature and history have articulated new logics intended to incite greater social and political agency within their fields. Building on Hannah Arendt's concepts of “natality” and “insertion,” 4 for example, literary scholar Amir Eshel argues for the importance of human agency linked with poetic language in his explorations of postwar and contemporary world literature and visual arts. The possibility of a “new beginning” points to the importance of human action and an open horizon of possibilities for change in the wake of the catastrophes wrought by the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century.5 As Eshel writes, futurity is “the potential of literature to widen the language and to expand the pool of idioms we employ in making sense of what has occurred while imagining who we may become.” 6

In this chapter, we will explore a handful of such practices to demonstrate that engaging with the future may be fraught but is not without precedent. To act by proposing even a fragment of the world we want to live in means we must inspect the spatial justice and injustice embedded in future designs, asking not only who we might be planning for, but also who is involved in the planning itself. Such scrutiny intrinsically involves checking our own privilege and assumptions. The power dynamics underlying speculations about the future are dangerous in so far as they remain tacit and raising them to the surface is a necessary starting point. Healthy, pervasive skepticism, a hallmark of modernity's criticality, however, can also serve as a roadblock to constructive agency. Scholars, in contrast to professional practitioners, can more readily take refuge in astute critique that reveals flaws in every potential action. And professions like architecture and urban planning have sometimes advanced futures that were numb to or had entirely misread social issues, as the history of urban renewal shows, or that serve the status quo without concern for equity or inclusivity.

For urban humanists, both postures are problematic, pre-cipitating the “generative imperative” as a call to action or, put more strongly, a responsibility to speculate.7 Academics and creative professionals are urged to engage with the future in a particularly imaginative way, a practice that engenders open, creative potentials in place of critical dystopias thrust at a weary society. In what follows, we pose several practices by which one might fulfill this generative imperative, including the idea of “immanent speculation,” or drawing out from the fabric of already existing reality the futures that should and could happen, linking speculation to discourses on imagination and ethics. Such practices can be found in unexpected territories, from utopian proposals and science fiction to environmental or other highly politicized art installations. We continue by applying Hayden White's notion of the “practical past” to discuss the notion of the “practical future,” a rigorous imagining of “what might come” that applies practical knowledge to our present moment and draws on the wealth of historical knowledge to shape and enlighten contemporary action. We conclude by discussing what speculation about the future, or futurity, may mean within the context of the urban.

Thinking Ahead, across Fields

The creative potential of an urban humanist to engage with the future is not reliant upon innate talent, empathetic capacity, or prophetic vision. Instead, it needs something that can come from anyone: the commitment to practice the future, a willingness to systematically engage with imaginative possibilities and tactics to effect changes. But before we delve more deeply into a practice that might be claimed as especially urban humanistic, what are the related ways of engaging with the future found in other disciplines?

Perhaps the most established practice of urban speculative thinking is the utopian tradition, which began with Thomas More in the early sixteenth century and most recently flourished in the postwar period among neo-avant garde conceptual architects like Archigram (figure 4.1), Constant, Kikutake, and Yona Friedman. Narrative utopias put forward imaginaries that served to critique the present more than act as a blueprint for a place that was meant to manifest in reality—as the very etymology of the term “utopia,” or “no place” suggests. By contrast, material utopias, or what urban scholar Lewis Mumford referred to as “utopias of construction,” seemed shackled with intrinsic problems.8 These problems include the need to isolate the utopian community from the rest of society, a concomitant disregard for the existing city, the tendency toward totalitarianism, and a guiding ideological singular purpose (e.g., leisure, equality, adaptability, education), to name a few. If and when a utopia is built, those same problems return with a vengeance.

4.1 “A Walking City” by Ron Herron for Archigram, 1964. Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Licensed by SCALA, Art Resource, NY

Architecture's experiments to create better worlds often fol-lowed the logic of modernism, which posited that a new city, one started from scratch and dominated by speed, technology, flexibility, and functionalism, could produce social transformation. The top-down organization of these schemes enabled the sites’ repressive character. As architectural theorist Reinhold Martin notes:

As so much critical social thought has demonstrated, state-based programs for the care and management of populations were notorious disciplinary sites. From housing to prisons to schools to hospitals, such sites were recognized as arenas for the reproduction of institutionalized norms that managed desire, suppressed dissent, and propagated a whole host of unfreedoms. Still all of these institutions . . . remain contested sites for the enactment of social justice.9

Modernist experiments took place in cities across the globe, from Tripoli and Chandigarh (figure 4.2) to Mexico City and St. Louis. These material utopias were variously flawed, which led to wide-ranging critiques of modernism as well as its utopian aspirations. The critical backlash remains so vehement that it has been difficult to separate modern architecture from utopian thought, to recuperate what might be of value from the latter (or the former). In a range between trivial and profound, all architectural work seeks to make the world a better place, or as Rem Koolhaas said, “every architect carries the utopian gene.” 10

4.2 Le Corbusier's plan for Chandigarh, India, 1951. Image credit: © F.L.C./ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019

Reimagining the future has also emanated from environ-mentalism most notably demonstrated in Ian McHarg's optimistic ecological approach for landscape architecture beginning in the 1960s (figure 4.3). Another direction for postmodernist utopian thinking is taken by intentional alternative communities such as Christianopolis in Denmark or Burning Man in the Nevada desert. From the perspective of urban humanities, both environmental and communitarian utopian thought hold valuable lessons, but they fundamentally require a tabula rasa model of development from scratch. If contemporary urban utopian thinking can gain traction, the historical lessons suggest that it will take root in existing cities, as a fragment rather than a holistic model. This fragment can be spatial, temporal, or both—and it operates as an experimental model that can grow or spread to other areas.

4.3 The Woodlands, a planned community in Texas designed by McHarg. Credit: Rick Kimpel, 2007. Sourced from Flickr

The architect and urban designer Roger Sherman has proposed an “if, then” logic for practices of engaging the future, one that is often used within architecture and urban design, albeit implicitly. Drawing on theories of complex adaptive systems and game theory, he notes the increment of a “change-inducing factor,” which can be tracked through myriad interconnections, causes, and effects to play out a series of futures that this factor can engender. And, in reverse, we might imagine a future and work backward toward a change-inducing factor that can be designed and deployed—as Sherman says, “it is doubtful that design can ever ‘express’ future change . . . therefore, all the architect can do is ‘set (design) the trap’ to capture potential change.” 11 Imagine, for example, that the emergence of autonomous vehicles may result in any number of possible futures: the elimination of private cars, the eradication of parking that is no longer necessary for continuously moving vehicles, the control of transportation by a handful of companies that only lease rather than sell cars, or the exacerbation of global warming because these companies are jointly owned by the fossil fuel extraction industry. But, then, imagine in reverse a landscape with no traffic, no pollution, and universal access to affordable transportation on the basis of autonomous vehicles. How, then, must the increment of the autonomous vehicle be designed, with all its materiality, urban, and socio-political embeddedness, to work toward that better future? If we can imagine it, we would want to “set a trap” for the future of pollution-free universal access and blockade the corporate-controlled scenario. This might entail focusing on solar-powered vehicles, vehicles designed for mass transit, and streets that accommodate cyclists, pedestrians, and autonomous public transit.

When imagining an if-then scenario set in motion by a change—say, for instance, a new building that is being planned—the designer is at some level narrating a fictional future. The narrative is a risk-free testbed, where material changes in the world are imagined but not effected. When architects design buildings, for example, they project into their drawings “doors swinging, drawers being pulled, corridors full of racing feet, people falling down unexpected steps, or jamming on landings.” 12 And if such fictions are particularly thoughtful and intensive, the architects hope to avoid unforeseen consequences.

Deyan Sudjic, in The Language of Cities, states that “cities are formed as much by ideas as they are by things; in either case more often than not they are the product of unintended consequences.” 13 The task for the urban humanist is to ground such ideas in rigorous, extensive study and to engage this work in propositional activity that grapples with these “unintended consequences.” This territory is fraught with danger because the very underpinnings of academic credibility are called into question, threatening values of objectivity, the use of unbiased methods, and the ability to weigh contrasting views. The danger stems from adding a new register to our interpretive structures, so that we are looking not only at what has transpired and is currently occurring, but also into the future.

Another genre of narratives that engages the future is science fiction. Leaving aside the recent, vast, and exciting literature around world building, two tactics that stand out were explored by literary critic Darko Suvin.14 The first tactic is estrangement: What are the realities that we face in our own contemporary world that are so daunting, or taken for granted, that the only way in which we can engage them is to take them out of our world, and put them into another? This same presumption is at the base of social theorist Karl Mannheim's deployment of utopia as a means to step outside all-encompassing ideological frameworks.15 Indeed, science fiction has been used time and again to deal with the most intractable problems of difference, othering, and identity found in American society. In popular media, Star Trek and X-Men deal with “aliens” and “gifted youngsters,” respectively, to engage readers (and watchers) with the notion of a future where questions of tribalism and learning to live with people unlike ourselves are pressing issues. Within the literature of Afrofuturism, the science fiction stories of Octavia Butler, such as the Xenogenesis trilogy, present characters who resist binary gender categories and have hybrid characteristics that are not only multiracial but also multispecies. Drawing on the deep histories of racial and economic violence, Butler's speculative fiction imagines alternative futures that both confront and resist the violence of the past by imagining possibilities for social and kinship structures out of the ruins of human-wrought catastrophes.

The second of Suvin's tactics is the novum: the framing of a hypothesis on the basis of a single new thing, which then has a dizzying array of consequences played out to their logical extreme. The most famous novum, perhaps, is that of time travel as explored in many works, from H. G. Wells's The Time Machine to the 2012 film Looper. But any number of other novums have been explored, from the ability to use the entirety of the brain (found in movies like Limitless or Lucy) to the presence of human-like AI (found in several of Isaac Asimov's books, or in the classic Blade Runner). The novum is similar to Sherman's change-inducing factor but here the focus is on exploring the logical implications of such a factor, rather than reverse-engineering the factor itself. This practice is especially useful for exploring the moral, ethical, and philosophical implications of a new technology, which are so often presented as value-neutral benefits to society rather than factors that have the potential to ameliorate or (more often) exacerbate the worst qualities of human nature and, in turn, society.

The tactics of science fiction engage with the future through narrative, fantasy, and play, but other fields hold their own models for thinking forward, and some of these may be useful to urban humanists. The most rigorously applied practice of the scientific method and inductive research, according to Karl Popper, also requires a leap into the future. As he describes in Conjectures and Refutations, the primary distinguishing factor that sets science apart from other human endeavors is, paradoxically, its limits: the best scientific theories are “prohibitions” from particular outcomes (e.g., the theory of relativity means we cannot travel faster than the speed of light); a scientific proposition is one that is limited in its capacity to explain the world (unlike, for example, the totalizing capacity of Freudian and Marxist theories that can explain the entirety of the world and therefore cannot be refuted); and science is distinguished not by its ability to confirm and explain but, rather, its ability to falsify and to test.16 But at the inception of any scientific project or finding of “refutation” is first a “conjecture.” That is, all scientific theories, laws, findings, and wisdom are tentative conjectures, guesses about the way the world operates, which await a future in which they may be falsified. According to Popper, the point is not to develop theories to explain the world and its future through scientific prediction. In fact, he specifically cautions that large-scale planning (as witnessed by authoritarian regimes in China and the Soviet Union) is both practically and theoretically unwise, since we cannot plan for the unexpected advances in our knowledge in the future. Instead, he teaches the importance of imaginative proposals and conjectures that may conflict with other proposals and that can evolve and change as they move forward in time.

Finally, moral philosophy and the study of ethics offer guidance to thinking through imaginative or projective scholarship. Kant to some extent distrusted the imagination, and the juxtaposition of imagination against reason persists in philosophical argument. For Kant, the imagination, because of its potential to be dominated by feelings, threatens moral judgment.17 But according to Jane Collier, philosophers have more recently recognized the impor-tance of imagination, particularly in literature, poetry, and the arts, and in moral deliberation, as long as rationality remains a “safeguard.” 18 As she notes, imagination is still characterized as a fundamentally corrupting influence over thought, which reason can protect against.

An alternative formulation of imagination's role in moral judgment, reflected in Eshel's notion of futurity described previously, stems from pragmatism and the work of John Dewey and John Rawls. Dewey reshaped the concept of moral imagination, a phrase coined by Edmund Burke in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, as the comprehension of the actual in light of the possible.19 In other words, imagination does not mean inventing entirely new objects but supplementing observation through “insight into the remote, the absent, the obscure.” 20 To propose the possible, that is, what is absent but potential, is inherently a moral deliberation. Thus, moral imagination enacts both empathy, that is understanding otherness, and what Dewey called “dramatic rehearsal,” meaning that moral deliberation is the imaginative process of depicting what is possible. Here, the relevance of architectural design is clear. But rather than dramatic rehearsals, design scenarios can be formulated as dra-matic predictions or experiments, in so far as they portray future possibilities so that both their intended and unintended consequences might be foreseen.

The important and defining question that remains is how to adjudicate among pluralistic views, power differentials, contested positions, and contradictory values. That is, if we are to imagine urban futures, how can spatial justice be ensured? Here important precedents stem from the discipline of planning with its deliberative and participatory imaginative practices. From Rawls's theory of deliberative democracy to Chantal Mouffe's agonistic democracy, participatory planning strategies seek to structure discussion of future change in a just manner.21 Mouffe extends the deliberative model to consider the impossibility of rational consensus in light of the crucial role of impassioned political beliefs. Even what might seem to be the most innocuous community meeting can quickly become a site where strongly held opposing views are voiced. “Mobiliz[ing] passions toward democratic designs” is a goal of agonistic pluralism.22 Such deliberations are often a mandated part of urban planning processes in order to give representation to affected constituents, but there are no established rules about how the aggregation or accommodation of different views should occur. The political and practical complications of participatory planning are apparent in dominant Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) planning narratives. NIMBY positions reflect, and ensure, the perseverance of status quo power relationships, which in turn reify racial privilege in a neoliberal economy. White upper middle-class residents, homeowners, long-term community residents, and economically stable residents are all privileged in the participatory process.

Thus, from practices as distinct as science fiction and parti-cipatory planning, we can see some of the outlines of how to think about the future. The broad contours of architecture, design, urban planning, literature, film, the social sciences, and positive sciences are full of gestures toward the future. Yet the work of research and intellectual thought often leaves “the practice of the future” as something unsaid, something implicit in our cultures, ways of knowing, and values. The urban humanities recognize the fundamental value and importance of the drive to engage with the future, and call for it to be made explicit and, moreover, prioritized in our all-too-often presentist or rear-facing engagements with the world of “what is.”

Practicing the Future

For urban humanists, then, the task is to imagine future possibilities. But what does it mean for scholars to think their work forward? Can we study a place and its everyday life rigorously enough, equitably enough, and compassionately enough to say something about what might be done to improve it, and for whom? Even if there are insufficient grounds to issue proclamations about what ought to change, are the perils of getting it wrong offset by those of inaction? If we learn about a contentious urban situation—say, where residents are being evicted along a new transit line—under what conditions can we venture into the debate with recommendations? If residents promote some future scenario, is the engaged scholar required to support it? The questions of agency, ethics, positionality, power, and spatial justice, prominent in other chapters of this book, echo loudly and clearly when we speculate about the future. To this chorus, it is the generative imperative of the urban humanities that brings a responsible, engaged, creative, and hopeful imaginary of new possibilities. To think forward toward a better world without creative direction is to condemn the future both to trivial adjustments to the status quo and to competent mediocrity.

We call this grounded imaginative thinking immanent speculation. It takes the possibility hidden in plain sight as its starting point. Paradoxically embedded in our inability to see anything beyond the present or the past, immanent speculation locates the spark of the future, the unknown, and the possible within these spaces.

If we are to posit immanent speculation as a fundamental practice of urban humanities, we must first grapple with the promise and peril embedded within the term “speculation.” And, again, we can start in our own backyard. Los Angeles is a city made from an assemblage of speculative practices. Spain colonized the region, surmising it was unsettled territory to be conquered, and decimated the Tongva, who had lived here for thousands of years. Later on, as part of the United States, the region went through a stuttering period of growth. Boosters proclaimed the magic of Southern California throughout the Midwest and elsewhere, fueling land speculation, as gullible investors would repeatedly and blindly bid up land prices only to discover, more often than not upon a first visit, that the real estate was essentially worthless. And, of course, people imagine they know Los Angeles thanks to Hollywood projecting moving images of fantasy plotlines onto screens around the world. Each of these moments in history is a variation of speculation—assumption, financial speculation, and fantasy—that demonstrates its danger when untethered from reality.23

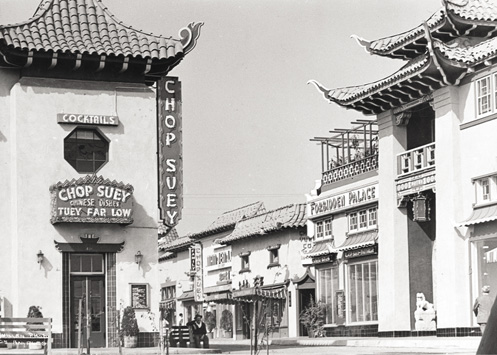

Across from La Placita, the mythical origin point of Los An-geles, is Union Station (figure 4.4). The last of the grand train stations built in the United States, it was approved in 1926 and completed thirteen years later during the throes of the Great Depression and with the world on the brink of war. A large portion of what was then Chinatown was demolished in the process, whitewashing the memory of the largest mass lynching in U.S. history with gleaming Spanish Colonial construction. It is the terminus of a city upon which it seemed almost anyone could project their own minor utopia. Sure enough, in 1938, a bigger, better Chinatown was built about a mile away under the guidance of community leader Peter Soo Hoo, and with the help of Hollywood set designers in designing its core, Central Plaza (figure 4.5).

4.4 Union Station under construction during the summer of 1938. Credit: Dick Whittington, Security Pacific National Bank Collection. Los Angeles Public Library

4.5 New Chinatown in 1939. Credit: Harry Quillen, Harry Quillen Collection, Los Angeles Photographers Collection, Los Angeles Public Library

To speculate might mean to assume rather than to know based on facts (as in Spain's imposition of a tabula rasa on California), or it might mean to envision historical or fictional realities (as in the imaginative work of Hollywood). There are, of course, endless varieties of financial speculation, such as land speculation or the mining speculation in the goldfields of Northern California and the oilfields around Los Angeles. We might read into Chinatown's destruction an element of racial speculation: that the sullied, foreign, Chinese landscape was envisioned by city boosters as bleached clean, transformed into a gleaming beacon of Anglo LA. But we might also see the inverse of that in a work of speculative fiction such as Karen Tei Yamashita's Tropic of Orange, a stunning kaleidoscope of new ethnic formations situated in Los Angeles.24 Decades of Anglo hegemony in the literature about Los Angeles have given us both Chandler's hard-boiled noir and Didion's upper-middle-class neuroses.25 Yamashita gives us Bobby: “Chi-nese from Singapore with a Vietnam name speaking like a Mexican living in Koreatown. That's it.” The book spans seven days, with seven narratives moving between Mexico and Los Angeles, just like its eponymous orange, which a character named Arcangel brings across the border. The book straddles magical realism and speculative fiction, suspending our disbelief about any number of perfectly plausible alternative realities for Los Angeles: palm trees as flags for the poor instead of street ornamentation for Beverly Hills, a traffic jam on the Cahuenga Pass as a meticulously conducted symphony, NAFTA as a luchador being defeated by el gran mojado.26 Yamashita pulls from her wealth of experience living in Los Angeles to produce a literary form of immanent speculation.

In the university, speculative work most often involves theo-retical development, from physics to philosophy. But there are some scholars today who, similar to Yamashita, eschew con-ventionally understood “academic speculation.” This new form of speculation is rooted in race and place insofar as it aims to decolonize. Immanent speculation is the practice of engaging with an inherently unknowable future in order to create the conditions for that future to unfold. It aims to decolonize the future from the forward march of time, from the imperfect conditions of the present, freeing it to become something just beyond what we imagine to be possible. Such speculations are immanent because they are not pulled from thin air, but rather from the sites and places in which we live: the seeds for unimaginable futures can be found in our messy, layered, and imperfect present.

It seems appropriate for immanent speculation, this act long practiced by a subset of artists and storytellers, to find its way into the academy in California's public university. The city of Los Angeles and, indeed, the state at large were shaped by a network of actors who were imagining the future so that it would become their reality. Judged on the empirical and positivist terms common to education, immanent speculation might be seen as a trifling distraction. Yet such speculative trifles, appearing ungrounded while actually dwelling utterly immanent to the spaces and places from which they rise, have the capability to construct not only what we imagine to be our future but, moreover, what we might even conceive of as possible in the future. It is this speculative practice that Percy Bysshe Shelley saw in poetry when he proclaimed, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” 27

At the same time, thinking forward is inherently risky, and there is much at stake both for the future imagined and the one doing the imagining. What are the perils for engaging the future in scholarly work? How might we think through the ethical questions that attend such work, and can we construct a new ethics for such scholarly imagination? The generative imperative abandons conventions (or fantasies) of neutrality by arguing that it is the scholars’ ethical responsibility to seriously consider what to “make” of their work. The real and problematic ethical quandary about potential negative impacts of propositional work has led to increasingly attenuated scholarship with a scope so narrowed and emaciated as to ensure its irrelevance. But here we offer the alternative ethical quandary: What damages are wrought by inaction? In urban humanities, the privilege of academic work is checked by deploying scholarly practices in pursuit of spatial justice.

Eric Cazdyn has explored what he calls a “non-moralizing materiality.” In the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, Cazdyn reflected on the immense and incomprehensible destruction through a proxy: the banal and weird emergence of the cicadas, their unmistakable and urgent buzz surfacing as usual, coming in and out of audibility, their songs lining their silence and vice versa. To anthropomorphize their behavior, their emergence, their desire to mate, their screaming calls, and their silence, is to set up a moral frame yet it is also to fundamentally not understand them at all. This is a common desire: to frame a situation by our preexisting understanding, rather than its lived materiality. Cazdyn links this parable to the aftermath of the disaster: “To moralize the Japanese disaster, for example, is to focus on the bad leaders, or the failed technology, or the well-mannered victims waiting patiently in food lines, or even on the inevitability of the disaster itself. To materialize the disaster, in contrast, requires not only resisting such a moralizing critique, but also reframing the event in order to mobilize it toward a radically different future.” 28

Here is the possibility of immanent speculation: in scholarly work, so often skewed toward the critical rather than the generative, we actually preclude the possibility of impact by focusing on the moral rather than the material. Rather than moral critiques that find affirmation among those who already agree and are ignored by those who do not, non-moralizing materialism pulls apart the threads of how something is actually existing, working, or acting, and points toward how it might radically change. Attention to banal material things and ordinary spaces of everyday life helps the urban humanist focus on opening a space for alternative futures. Finally, by opening possibilities and making them public, our scholarly engagement is itself available for the kind of critique that furthers the necessary (if not sufficient) collective discussion to advance spatial justice.

In one project conducted by urban humanities students, in LA's sister city of Mexico City, the metro system upon which millions of people take their daily commute is reimagined not as an alienating space to pass through, but as a site of human connection, a destination for performance of the self (see Project F: The Gentegrama Project). This immanent speculation pulls from Mexico City's metro system's prominent station iconography to develop “Gentegrama,” a project of reflection upon urbanism, infrastructure, gentrification, and the increasing speed of our socially mediated world.

The Practical Future

Who is the future for? In a set of interrelated essays written at the end of his life, the philosopher of history Hayden White reflected on the ethical stakes of various narrative forms of engagement with the past, suggesting an answer to these questions. He argued that the “historical past”—a dubious narrative construct created by professional historians to organize events into meaningful units—is a product of the nineteenth-century drive to make the discipline of history into a science. Rooted in an objectivist, empiricist logic, these historians believed that past events could be resuscitated by following science-like rules for constructing it as “it really was.” In contrast, White argues that the historical past exists “only in books and articles published by professional historians; it is constructed as an end in itself, possesses little or no value for understanding or explaining the present, and provides no guidelines for acting in the present or foreseeing the future.” 29 This is because it is an abstracted, distant construct, divorced from contemporary social realities and political exigencies. No one, he goes on to argue, ever “lived or experienced the historical past” since it is constructed ex post facto, from a perspective and with knowledge that historical agents could never have had, let alone ways of organizing or explaining events that draw on later knowledge. Yet this was not always the case: in ancient, medieval, and even modern times, history was a pedagogical, rhetorical, and practical discipline that offered guidance, counsel, and lessons to help answer ethical questions. While there are certainly a great many scholars who continue to practice history in a public and practical fashion, White's provocation coincides with larger arguments and concerns regarding the “professionalization of the academy.” 30

In The Practical Past, White probes the origins of the discipline of history's professionalization to critique its inward-focused scientism and to champion, instead, historical writings that come from outside the professional field—in other words, the engagements with history that we might find in art, literature, and folklore—which serve as guideposts for action in everyday life. White's concept of the “practical past”—in contrast to the “historical past”—is borrowed from philosopher Michael Oakeshott and explicitly echoes Kant's notion of practical reason, that is, moral and ethical judgment about what we should and should not do. The practical past, White writes, “refers to those notions of ‘the past’ which all of us carry around with us in our daily lives and which we draw upon, willy-nilly and as best we can . . . [it] is also the past of repressed memory, dream, and desire as much as it is of problem-solving, strategy, and tactics of living, both personal and communal.” 31 In this sense, the practical past is applied, strategic, emotive, and ethical, helping us play out scenarios and providing guidance for thought and action.

We might ask: How might we conceive of a mirror com-plement, so to speak, to White's defense of the practical past as a way to think about speculation and the future? If we take some imaginative liberties with his text and replace instances of the term “historical” with “speculative” and “history” with “the future,” we read something like the following:

Recent discussion on the periphery of mainstream [speculative] studies has revealed the extent to which “belonging to [the future]” (rather than being “outside of it”) or “having a [future]” (rather than lacking one) have become values attached to certain modern quests for group identity. From the perspective of groups claiming to have been excluded from [the future], [the future] itself is seen as a possession of dominant groups who claim the authority to decide who or what is to be admitted to [the future] and thereby determine who or what will be considered to be fully human. Even among those groups which pride themselves on belonging to [the future] (here understood as being civilized) or in having a [future] (here understood as having a real as against a mythical genealogy), it has long been thought that [the future] is written by the victors and to their advantage and that [speculative] writing, consequently, is an ideological weapon with which to double the oppression of already vanquished groups by depriving them of their [speculative possibilities] and consequently of their identities as well.32

White's trenchant writing on the historical past might equally be applied to consider the ways in which imaginations of the future have, similarly, been co-opted, colonized, and controlled by particular powers and groups. Any group, and especially scholars and students who purport to desire radical and decolonizing action, must consider the need to rethink who can possess the future, and how such speculation ought to happen. We argue that White's concept of the practical past is equally informative in constructing a notion of the practical future. We all have a sense of “the future”—what we expect to happen, what we think lies within the realm of possibility, what we hope will come true—and we draw on these conceptions intentionally, and at times subconsciously, when we go about our lives. We use them to guide our decision-making or to help us solve problems as much as they are at times repressed dreams and desires. Where White sought to incorporate writers of historical fiction into the canon of the practical past—Sebald, Hugo, and Flaubert, for example—we might incorporate speculators of the future: Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin, Octavia Butler, and others to enable us to create imaginative frameworks, possibilities, and values that help us construct a more equitable, more accessible, and more democratic future. In other words, the practical future considers ethical questions centrally within speculative thought.

In our preceding “translated” text, we might imagine that professional and expert predictors of the future are in danger of evacuating the future of its possibility by reducing it to abstracted statistics and scientific rules. The future—like the past—is a domain able to be staked out, fought after, and controlled, and as such, it is deeply enmeshed with power dynamics. Ultimately, the practical past and the practical future cannot fully be separated since our human capacities for speculation will always derive from the contingency of our knowledge, the positionality of our ways of seeing and knowing, and our imaginative wells steeped in the logics, epistemologies, and sediments of our times, places, and languages.

Rather than reifying or echoing such power dynamics, White instead draws our attention to the “practical”—that is, ethical—possibilities of fashioning historical narratives, which we might add are always speculative narratives. The practical past, like the practical future, is an approach to storytelling and narrative more generally that foregrounds the ethical question of what we should or ought to do. How, then, are we to use and interpret those speculations of the future that can both open up new possibilities and provide ethical guidance for how to act? Certainly, science fiction, or other speculative forms such as architectural plans, visionary films, and conceptual art are not meant to be read literally as an instruction manual for how to move into the future. They function as modes of emplotment for creating possible futures and in this sense are about the ethics of imagining and making. Perhaps for this reason White concludes with the idea that the practical past is “shifting the burden of constituting a useable past from the guild of professional historians to the members of the community as a whole.” 33 Again, we can imagine a version of this statement about the guild of professional scholars responsible for predicting the future, called to open up agency from a preordained future toward a practical future, opening up the possibilities that the future has to offer to those who might have otherwise been excluded from the realm of the speculative “sciences.” The practical future, like the practical past, is porous, publicly oriented, ethically engaged, and imaginatively poetic.

Project F: The Gentegrama Project

Mexico City

4.6 Proposal for interactive signage at La Raza Station in Mexico City. Credit: Authors

Alexander Abugov, Thomson Dryjansky, Carlos Guerrero Millán, Ryan Kurtzman, Paloma Olea Cohen, and Danmei (Melanie) Xu

Have you ever been underground with thousands of others? You cram into the same train com-partment, while attempting to keep perfect emo-tional distance from one another. Finally, you step onto the escalator that will resurface you back to the reality above. The station you are about to enter, La Raza, is a transfer station in Mexico City that combines the underground transport for Line 3 and surface rail for Line 5. In envisioning La Raza in future tense, we invite you to reconsider the corridors that you rush through daily instead as a terminal destination where social interaction, interpersonal communication, or even collective disruptions take place.

Gentegrama is an interactive display tech-nology and wayfinding system for the stations of Metro CDMX (Mexico City's metro system). “Thickening” the station pictogram's original design—a design that was conceptualized by American graphic designer Lance Wyman in 1968, the year of the Olympics and of the Tlatelolco massacre—the Gentegrama will offer a polyvocal, community-informed representation, while si-multaneously retaining its original wayfinding function. Gentegrama changes its purpose from “passive” display to the dynamic and ever-shifting representation of the constituent users.

Geolocated and hashtagged social media posts are displayed as a changing image feed on the station signpost (figures 4.6 and 4.7). These social media posts have a lifespan of thirty-six hours, allowing for communication across days and work schedules. Posts are also uploaded from interactive panels located in the stations. Using this device, users can “like” images from the feed, extending their display time. To focus on the input from the actual users of the station, “liking” can only occur from the in-station device. There is also a station feedback component that would collectively create a mood temperature map of the entire metro system.

4.7 Illustrations of Gentegrama proposal. Credit: Authors

While users may add to and browse the image feed from their cellphones, the heart of the installation is the interactive panel. The in-station Gentegrama installation offers accessibility to those without smartphone technology. Users may browse the feed, like and upvote images and take pictures of themselves, others, and the station.

Another unique feature of the Gentegrama design is the station feedback feature. Passersby can weigh in with their feelings and opinions about the station and its condition with the single push of a button. This is visualized as a colored stripe on the display. It functions as a collective barometer to users within the station and is exported to the administration as a map of the entire system. Finally, crowdsourcing, as a strategy heavily employed in Gentegrama, can be employed in creative and open-ended ways by the public.

As the Gentegrama project evolves through user interaction, we imagine that Gentegrama will grow out of its physical confines of navigation stations and into the digital world. Gentegrama will replace all existing pictograms, whether online, in information stations, or on the screen of other transportation systems like the bus or suburban rail. We envision an app for your phone, allowing new connectivities between stations and mapping your transit journey.

Interlude 4:

Shanghai

The House on Xinhua Road

4.8 The family is present in the contemporary city, The House on Xinhua Road. Credit: Authors

I created two linked digital video projects as part of the Urban Humanities Initiative's Shanghai year (2014–2015) to offer a portrait of a house that once belonged to my family, and is located on what was the city's western fringes during the 1930s. The first film was created from afar in Los Angeles out of archival materials, drawing from both primary sources and my family, including photos and Super 8 film footage of the house, and secondary materials on Shanghai. The second film was built out of live footage captured during the experience of returning to the house. The videos utilize two different film-media strategies developed in the Urban Humanities Initiative: the archival essay film and filmic sensing. The weaving of my own subjective experience in both films adds another dimension, used to shape the narrative of the first film, which comes into tension with the real-time unfolding experience of the second.

My family's former home has changed its function during its existence spanning more than eight decades of Shanghai's turbulent history. It sits off Xinhua Road, down a small lane, with other old houses on either side, remnants from a different era. In the present, you walk down the lane and come to a gatehouse and a newly built fence. Behind, apartment blocks of contemporary Shanghai rise up into the sky, creating the sort of visual intersection of past and present that is so common in the city. Noise from the surrounding streets can be heard in the distance, but it seems strangely far away, as if the weight of the past eighty years is heavier here, giving the house a certain silence that speaks of its role as a witness to a changing city.

In March 2015, I stood in the lane pressing my face against the cold metal of the fence and gazing at the house through a small opening between panels. Here is where my grandmother grew up as part of the city's Chinese elite. After the house was confiscated by the government in the 1950s, it took on different functions during the socialist period. Since China opened up in the late 1970s, it has continued to change functions, and my family has regularly returned to the house, bearing witness to the ways that it has changed along with the city around it. We do not own it any longer, yet it serves as my family's central reference point to the city, a way to understand Shanghai and our connection to it (figure 4.9).

4.9 Film still from The House on Xinhua Road. Credit: Authors

Since I was last in Shanghai, a few years before my filming project, the function of the house has again changed. Through researching for the film and combining this research with knowl-edge of family members, I constructed its history. The house was built in 1935 by Zhao Chen and Chen Zhi of The Allied Architects, members of the first generation of Chinese architects in Shanghai. It was built as a two-story Spanish-style mansion with green glazed roof tiles, steel doors and windows, and cement outer walls.

In the 1930s, Xinhua road was called Amherst Avenue. In 1947, it was renamed Fahua Road. In 1965, it gained its current name: Xinhua Road, Xinhua meaning “New China.” Each house in the development was built in a different western style. As British sci-fi author J. G. Ballard, who grew up here, describes, “the French built Provencal villas and art deco mansions, the Germans Bauhaus white boxes, the English their half-timbered fantasies of golf-club elegance.”

My great-grandfather, a prominent lawyer of the Republican Era (1912–1949), moved his family into the house, and they were its first residents. My grandmother grew up in the house, coming of age in a city occupied by the Japanese after 1937. After the war, she would marry in the yard of the house before leaving for America in 1946, never to return. The rest of the family would follow, settling in the United States, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

After 1949 the house was left empty, taken over by the new communist government. In 1959 it was given to the Changning District Military Sports Commission and made into a gymnasium, with its green lawn concreted over into a basketball court. By the 1980s, it had become a government office and later a Japanese restaurant. During the 2000s, it became the WTO conference center, which led to its restoration and historical protection, and now it has evolved into something less discernible. This is part of the larger reappropriation of Shanghai's old houses and other historic buildings happening in the process of reglobalization.

On the screen, a grainy image of a house appears: it looks old and used. Previously, the viewer has been oriented with images and sounds of Shanghai, in order to open a portal to the past: a shot of the city skyline, a map of the pre-1949 city, sound tracked by an old Chinese jazz song. In the film, my family are almost like ghosts, and their images bleed into those of the Super 8 footage, which moves through an emptied-out version of the house (figure 4.8). The time contrast is some thirty years, an ocean of time and trouble in Shanghai's history, with the footage taken after China's awakening from the Cultural Revolution. The film highlights visually this sense of temporal loss, and the narrative voice shifts slightly, no longer recounting history but taking an investigatory tone, “I seek memories in empty rooms, to reconstruct what may have been . . . looking for connections.” In the film's dénouement, the images of the family and the house reappear collaged into the contemporary and future depictions of the city (figure 4.10), concluding that the city is “a refuge of memories” that leads to the future.

4.10 Time layers of the house on Xinhua Road. Credit: Andre Comandon

The second film starts with the camera following me walking down the lane to the house. It does not show the scene of a man coming out, refusing to let me visit the house, and slamming the door on my face, but focuses instead on the emotional aftereffects, as the camera locks onto my face, and the image of the house comes in and out of focus. The film ends with shots that contrast my view of the house with the reactions on my face: anger, grief, reflection, ambivalence, acceptance.

The two films represent an attempt to express the complexities and layers of history, time, and memory that can manifest in a single place within a city, while at the same time universalizing the experience in order to communicate something larger about Shanghai. What will become of the house (figure 4.11)? That I cannot say, but I do know that I will return to it again and again as a reference point and continue to read Shanghai's changes through its windows and walls, perhaps finding new ways to film and present it.

4.11 The house in June 2018. Photo credit: James Banfill