Early submarine evolution is marked by a struggle to overcome the problem of how to propel the submarine efficiently both on the surface and submerged. This engineering challenge can be divided into two interrelated concerns – hull form and propulsion. The propulsion problem drives the hull form problem.

The US submarine of 1945, embodied by the Balao and Tench classes, suffered from two serious shortcomings – limited underwater range and inadequate speed. To run completely submerged the submarine had to operate on its battery/electric motor combination alone. The range in this mode was 10 nautical miles (nm) at 8 knots or 50nm at 2 knots, the difference due to the batteries’ ability to supply a large quantity of amps (high discharge rate) for a short time before they were exhausted and had to be recharged. A smaller discharge rate meant the boat moved slower but could do so for a longer time. An answer to this range endurance problem was the snorkel, a small induction pipe that reached above the surface and supplied air to the diesel engines, allowing them to run while the boat was submerged. However, the snorkeling submarine is noisier by far than one running on the same number of engines on the surface, and quietness is part of the submarine’s underwater advantage.

Polar bears examine a Sturgeon Class boat surfaced in the Arctic. When surfaced in the ocean for a swim call, the boat crew posts an armed shark watch. When surfaced in the Arctic, the boat has a polar bear watch. Even though the person is armed, his main job is not to kill the bears but to warn personnel on the ice that a bear has been sighted. On the occasion of a sighting the ice is evacuated, leaving the bear in charge of the territory.

The speed issue involved a rethinking of the entire outer shell (hull) design. A first step was to remove all the things that caused flow resistance, thus wasting energy. This modification cut the flow resistance of the World War II fleet submarine by nearly 50 percent, and was one of the principal measures of the Guppy conversion of many World War II boats. (Guppy was the Greater Underwater Propulsion Program, which extended the useful postwar life of diesel-electric submarines by removing items such as deck guns so as to streamline their hulls, increasing battery capacity, and the addition of snorkel systems.) For a given hull design, however, an increase in speed is directly dependent on the amount of power put into the water, and equates directly to shaft horsepower (shp). Speed is related to a change in shp as the cubic function of the change. Thus to go from 5 to 10 knots (doubling) requires an eightfold (two cubed) increase in shp. To go from the maximum 10 knots short-term submerged speed of a fleet submarine to the expected short-term speed of 15 to 20 knots of a replacement design required an increase from 5,400shp to over 18,000shp. Motor and battery designs capable of this horsepower would be huge and much too large for submarine requirements. Something else had to take the place of the diesel-electric design. Fortunately, a new source of energy was becoming available that would change everything.

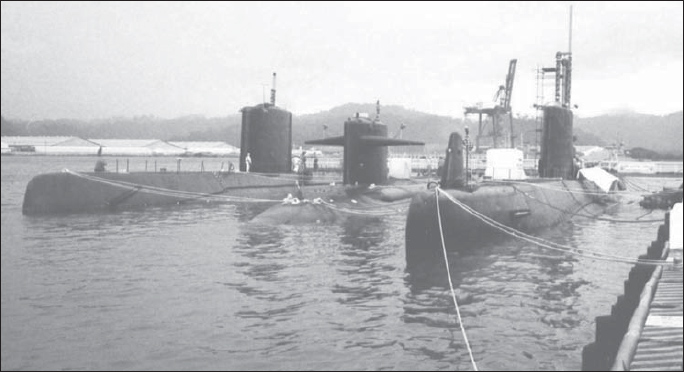

From left to right: a Skate Class, a Permit Class, and a Tang Class. The two outboard boats are nuclear. The inboard boat is a diesel-electric. The fin-like protrusion on the bow of the Tang Class boat is the forward hydrophone set for the BQG-4 PUFFS sonar system, which became the Wide Aperture Array portion of the BQQ-5 on the Seawolf and Virginia Classes.