A word is necessary here about Admiral Hyman Rickover. His name has become synonymous with the United States naval nuclear power program. In fact, it is commonly believed that he personally designed the nuclear propulsion plants. The admiral was a brilliant engineer, but more than that he was also a brilliant manager. He saw that in order to build and maintain a safe and effective nuclear propulsion system in the Navy, certain things had to happen outside the realm of actual system design. Perceiving that there were inherent dangers in the use of nuclear reactors, he set in motion changes in the way the submarine navy (and later on the surface fleet) did business. Fleet submarine systems were simple enough that operations and maintenance were done on the basis of “corporate knowledge,” with minimal use of technical documentation. The senior petty officers supervised this maintenance and passed on their expertise to their juniors. The worst that could happen if an error was made was some deranged equipment or less than optimal operations. However, the nuclear reactor made the “worst case condition” much worse – the concept of an accident took on a whole new meaning. To counter the danger, Admiral Rickover set in motion a strict regimen of operation and maintenance. Documentation was created that set forth how the plant was to be operated and how maintenance was to be performed. This documentation was to be followed precisely. Technical training was codified and intensified. Nuclear powerplant operators (colloquially called “nucs” – pronounced nooks) had training on the actual powerplants after their initial technical training as machinists, electricians, and so on. The training was intense and tended to weed out all but the most dedicated and capable operators. In addition, Admiral Rickover extended the reach of this quest for excellence to the shipyards that built the subs and the contractors and vendors that supplied materials for the construction and maintenance of the boats. His requirements were written into the specifications and contracts. Only those who could meet the specs did business with the Navy. This meant that that there was full accountability from the vendor who supplied the parts through to the operator who used the parts and everywhere in between. That the nuclear propulsion plants in US submarines have such a good safety record and are perceived by the general public to be safe is the legacy of “The Admiral.”

In order to allow personnel to pass through the reactor compartment safely, a narrow passage was part of the design of all fast attacks. The tunnel was shielded against the types of radiation expected from the reactor and its attendant systems, thus allowing a safe transit through the compartment.

It’s April 2, 1991, and it’s dark outside. In the control room of the USS Pittsburgh (SSN-720), however, it’s blue, red, amber, and green. The blue is from the lights that during the day would be white, but which now are rigged for night and cast a relatively dim blue aura over everything. The other colors come from indicator lights, sonar displays, and computer screens. The crew is at battle stations. They have been to battle stations nearly daily for the past month. The boat is deep in the dark confines of the Red Sea. However, this day, the battle stations would be different. Instead of being practice and training, what was to happen would be real. There was a certain tension in the air and a lack of some of the banter that might be present during practice runs. The officer supervising the fire-control stations makes a report to the captain that the required targeting package has been entered into the Tomahawk missiles that reside in the launch tubes at the forward end of the boat. The captain acknowledges this information then orders the boat to proceed to launch depth. The sonar supervisor calls out the changes in the contacts held by the sonar system. He ensures the surface of the water is clear of any intrusive ships and that no hostile submarines are lurking. In a manner similar to that seen in the movies, the captain calls out, “Firing point procedures.” Procedure manuals are already open to the proper pages and checkoff sheets are at hand. The control-room personnel do all the things that are listed. The tubes are ready, the missiles are ready, the ship’s position is proper, and the crew is prepared. The captain orders “Tube one, SHOOT.” Buttons are pressed and the boat gives a slight shudder. The fire-control system supervisor announces, “Missile away, tube one.” In the night sky above the submerged submarine, the missile breaks the surface, its booster ignites, and the calm waters are lit with an eerie light. The missile arcs away and heads for its intended target – downtown Baghdad’s Iraqi command-and-control center. Operation Desert Shield has just become Desert Storm and the air war has begun. The missiles were part of the initial effort to silence the Iraqi air defense. It is not the only time that Tomahawks have suddenly and without warning burst from a quiet ocean and headed off for a distant target. One of the advantages of a submarine is that it can lurk unseen off the coast and reach out over 1,200 miles to put a warhead on a target. It has been said that the attack launched by the USS Pittsburgh and the USS Louisville on that April morning was singularly successful.

This is one of the Los Angeles Class that has bow planes instead of sail planes, and it sports a 12-tube VLS from which Tomahawk missiles are fired. The sail is also hardened to be able to punch through the Arctic ice.

Los Angeles Class boat in dry dock. Proper maintenance and repair is vital if a submarine is to keep its operational commitments. All bases have either access to naval shipyards with dry docks and/or floating dry docks, such as are shown here. With the boat completely out of the water, work on the underside and on hull valves can be accomplished.

The above description is an approximation because the actual records are classified. The operational logs for all US Navy nuclear fast attack submarines are kept on the ship, or if the ship is decommissioned at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). In any case, these logs are classified and unobtainable for the general researcher. Some tidbits of information have become public, however, but the evidence, although from reputable sources, is anecdotal for the most part. What is evident, though, is the importance of the role played by the fast attack submarine in the Cold War.

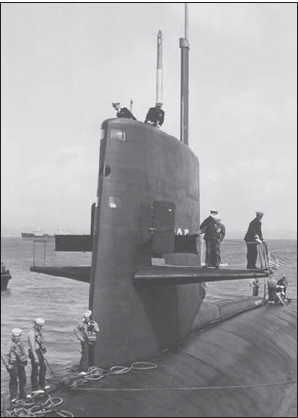

Modern submarines are built specifically to travel completely submerged – their round hulls with no rolling chocks and their low bridges make them miserable in any significant seaway. This photo is of a Skipjack Class boat, which had the highest of all the fast attack sails, trying to make a high-speed surface run.

After World War II the United States and its allies had to keep close tabs on the Soviet navy and learn about the environs of the Barents and North Pacific areas. Starting in 1949, submarines of the US Navy (and presumably others) ventured into these areas to conduct oceanographic research to learn about everything from sonar conditions to the ability to communicate by radio in the far north. At first these operations were carried out by diesel-electric subs. They set up early-warning “barrier patrols” and watched for a possible “breakout” of the Soviet navy around the North Cape and down through the Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom (GIUK) gaps in the Atlantic and out around the Kirules and down past Tshima Straits in the Pacific. As the nuclear fast attack submarines came on line they took over these tasks, maintaining a continuous presence outside all the Soviet naval ports. The surveillance took on more and more rigorous tasks as the abilities of the boats were tested and advanced. Acoustic and electronic signatures were taken and recorded, deployment times and patterns were observed, even photos of the undersides of Soviet naval vessels were taken and vessels followed. These actions were rolled out on a continuous basis, 24 hours a day, every day. For the last four decades of the 20th century and into the present century, the fast attack submarine has kept a non-stop watch.

A fast attack submarine on the surface provides little in the way of freeboard or a safe deck to work upon. The sail doesn’t stick up very far and in a moderate seaway is wet. To surface and attempt any useful work such as a rescue at sea is difficult at best and highly dangerous.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union several high-ranking Soviet naval officers have stated that this continuous presence of silent, unobserved submarines was a significant reason for the end of the communist regime. It is a very real fact that the invisible presence of fast attack submarines figures highly in the military thinking of nearly every country, especially as those submarines can launch high-explosive weapons that have a range of over 1,000 miles and aiming systems that can pick which floor of a building to hit. This ability was proven several times before and during the Desert Storm battle and in the conflicts of post-9/11. In this world of new types of conflict, the standard view of a submarine – its periscope sticking up attacking a convoy of enemy ships – is as dated as ships of the line meeting in a yardarm-to-yardarm fight. The role of the modern submarine in today’s world is being debated by naval experts all over the world and the jury is out.

Some little-known and unusual events that have become public present a different face of the fast attack submarine. First to set the scene. A fast attack submarine is at home in the deep. It is a roundbottomed vessel with good longitudinal stability, but “rolls like a drunken pig” when on the surface on any seaway. The only saving grace is that they have one hatch open to the bridge and take little water, if any, into the interior. But the time they spend on the surface is minimal and, in general, submariners have little time to obtain “sea legs.” Two fast attack submarines, however, have performed exemplary rescues at sea in severe storms.

Los Angeles Class submarines can be quickly adapted to dock the Deep Submergence Rescue Vessel (DSRV) and carry it to the scene of a submarine in distress. Here the USS La Jolla (SSN-701) has been fitted with the rescue vehicle Mystic (DSRV-1) for submarine rescue exercises.

PLATE F

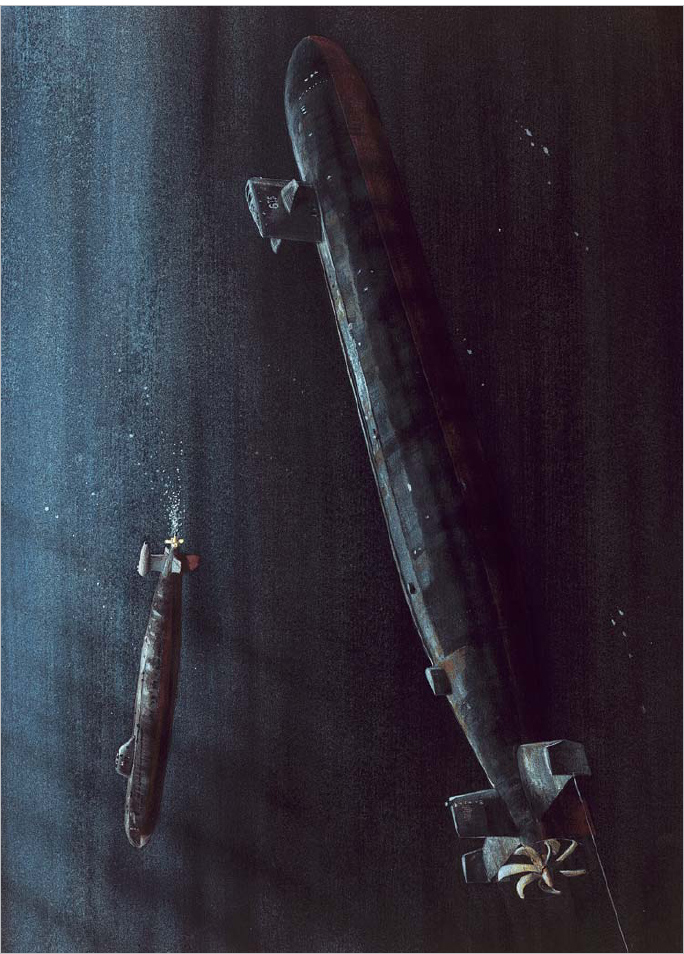

One of the more interesting tasks assigned to nuclear fast attack submarines during the Cold War was following a Soviet warship, many times a submarine, to acquire information as to its acoustic signature and its operational methods. This task, called “trailing” meant many days of intense concentration by the trailing submarine’s crew. Shown here is a Sturgeon Class US submarine following a Soviet Victor III which has just made a sharp turn to port. This maneuver was performed at random intervals so the submarine could check the area directly behind it in an area called the “baffles.” This area is masked from the ship’s sonar by not only the sonar’s position (in the bow) but by the turbulence set up by the submarine’s screw. The maneuver is called “clearing the baffles” but has been popularized in books and movies as the “crazy Ivan” maneuver.

On July 8, 1972, the USS Barb (SSN-596), alongside in Apra Harbor, Guam, and nearly ready to get underway, received an “operational immediate” message. A B-52 bomber, call-sign Cobalt 2, had gone down at sea some 300 miles from Guam. All ships were to proceed to the area to effect a rescue. There were two submarines that could respond quickly. One, the USS Gurnard (SSN-662), was underway transiting from Japan and was nearing Guam. The Barb was the other. Within an hour Barb was underway and just outside the harbor it submerged to make best possible speed to the crash area. Things were quiet below while the submarine sped to the scene. As it drew closer Commander Jergens, captain of the Barb, slowly brought the boat from the depths toward the surface. The crew had rescue equipment at the ready in the control room and had reviewed the rescue plan they were to implement. As they came toward the surface the boat started to roll more and more. A storm had reached typhoon strength, forcing all the possible surface-ship rescuers to run for cover lest they also needed rescue. Gurnard was still too far away, so Barb became the B-52 crewmen’s only hope. Ten degrees rolling each way became 20 then 30 and grew more as the boat surfaced. The captain tried to find a course that would both close on the raft and minimize the rolling. Heading into the sea was not an option because the bridge, only 15ft off the water in a calm sea, was forced under when the boat ran under an oncoming wave. An orbiting aircraft dropped other rafts and flares to direct the submarine to the survivors. Inside the boat the crewmen, not used to the rough weather, were sick, thrown about, and generally miserable, but their thoughts were not only on their own safety but the rescue of their fellows adrift in the massive storm. Just after eight in the morning the bridge was again manned and other members of the rescue team rigged lifelines on the fairwater planes. With the raft being blown nearer and nearer, Jergens made an upwind approach and shotlines were fired to the survivors. However, these thin lines broke again and again. Chief Heintz, on the bridge with the captain and the officer of the deck, volunteered to swim to the raft to assist in the rescue. Between Heintz and Petty Officer Spaulding (who was one of the more muscular of the Barb’s crew), a heavier line was put across and the actual rescue started. One of the airmen had broken his arm in the ejection, and was first to be hauled up. Spaulding held onto the rescue safety line and as the boat rolled one way pulled it in quickly. As the boat rolled the other his strong arms plucked the airman from the water like a fish on a line. Soon all the crew were deposited in the control room and carried down to the crew’s mess, where the corpsman awaited to deal with injuries and any other problems. Gurnard had now arrived on the scene and was commencing a rescue attempt on the plane’s captain, who was in another raft. The 70-mile-per-hour winds and 30ft-plus seas were playing havoc with her attempt to get in position. Finally, after hours of being vectored by aircraft to the other raft, Gurnard plucked the last survivor from the sea. So in addition to the sur-veillance, trailing, and myriad other operations over the 50-year history of the nuclear fast attack, rescue at sea can be added to the list of accomplishments.

The Los Angeles Class fast attack submarine USS Dallas (SSN 700) heads to sea following a brief port visit. Dallas is the first Los Angeles Class submarine to have a dry deck shelter. Dry deck shelters provide specially configured nuclear-powered submarines with a greater capability of deploying Special Operations Forces.

PLATE G

One of the tasks performed by nuclear fast attacks is one they are ill equipped for. However, when called upon, they will race to a scene to attempt a surface rescue of those in “peril on the sea.” One such rescue was performed by the USS Scamp (SSN-588). In the cold North Atlantic the boat answered the call to rescue sailors in distress. She surfaced in the middle of the storm to try to help. Being round bottomed and short, the Skipjack Class submarine is ill suited for surface operations and the sailors inside are not used to rough seas. The submarine’s crew fastened everything inside down and prepared for a rough ride. Surfacing near the liferaft she tried to get a line over. The seas were slamming against the sail, one wave tearing off the access door over the sail planes. Finally one of the crewmen from the sinking Panamanian freighter was rescued. Unfortunately he was the only one to survive.

During the rescue by USS Scamp, the doors that lead from the inside of the sail to the sail planes were torn completely off by the fury of the waves.

When a submarine reaches the end of its useful life, it is decommissioned in a formal ceremony. The national ensign and commissioning pennant are taken down and the crew departs the ship. Then comes the process known as the Submarine Recycling Program (SRP). The boat is placed in a dry dock and the reactor core is removed. The entire reactor compartment is then cut out intact. The core is transported to the Navy’s radioactive waste storage facility in Idaho and the reactor compartment is sealed and barged to a storage facility in Hanford, Washington. The ship is then stripped. All useable parts such as electronics and habitability items are stored for immediate reuse. Wiring and cables are pulled out to recycle for their copper. Hull and piping steel is cut up for reuse. This steel, along with other metal structures and piping, is of a high quality and is much valued. All the parts and material that can be recycled or salvaged in any way are separated, sorted, and shipped off to the appropriate facility.

The submarine is then slowly taken apart until nothing is left but the records and the memories. In some cases, however, parts are preserved in memorials and museums. Sail structures in particular are sought after as parts of museum complexes. In Groton, CT, for example, as a part of the Naval Submarine Museum is the sail of the USS George Washington, the first ballistic missile submarine.

This photo, taken in the early 1990s, shows the reactor compartment storage trench in Hanford, WA. This will be the final resting place for submarine reactor compartments until the radioactivity level drops far enough to allow the metal to be recycled. That will be a long time from now. This trench is now nearly full.

Fast attack submarines of the US Navy have a long and proud career. They continue to be sailed by highly professional men who see their job as vital in the maintenance of peace and the lynchpin of the United States’ global naval strength. Always ready, always there, never seen.

A Los Angeles Class submarine with a dry deck shelter on the after deck. This served as a lockout chamber for SEALs and was accessed from inside the boat through the operations compartment hatch. The shelter could house the SEAL team equipment and a SEAL delivery vehicle.