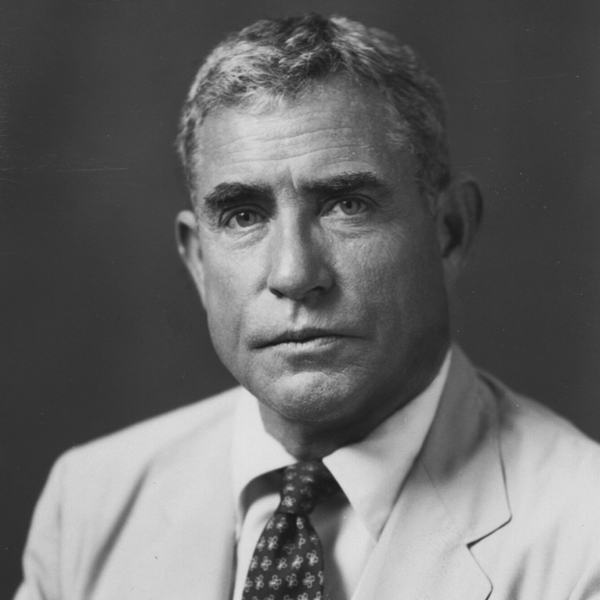

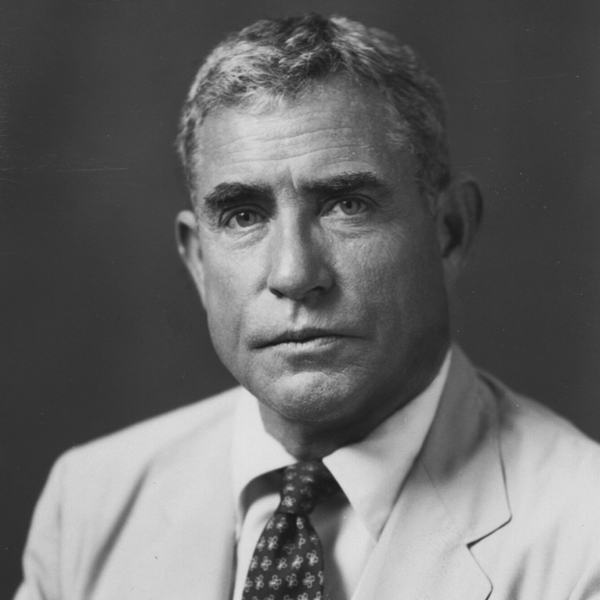

Paul Patrick Kennedy, Mexico City, 1959.

Nothing Fancy: Recipes and Recollections of Soul-Satisfying Food is just that, with a few fancy exceptions, of course. Originally published in 1984, it is a collection of recipes that are, or have been at one time or another, part of my culinary life—favorite dishes that I love to eat and remember friends by. Some of the recipes come from my rather traditional upbringing in England, others stem from ideas that I have picked up while traveling and eating, and some I have just plain invented in my search for new textures and tastes to go along with the old.

Mrs. Beeton included in her famous book on household management home remedies for measles, scarlet fever, croup, and diarrhea, and Martha Washington the same, while my Mexican “bible,” La cocinera poblana, states clearly on the title page that it includes “varied recipes, secrets of the dressing table and domestic medicine to preserve good health and prolong life.” And now that there is a more holistic approach to good health and food, I shall include, raised eyebrows notwithstanding, a few little natural remedies that have become part of my everyday life.

I love to cook the occasional complicated recipe purely as a culinary exercise, following the instructions to the letter, and then, inevitably, I begin to improvise. I have so often heard, “I have improved on so-and-so’s recipe”—to me that smacks of arrogance, when one knows only too well what goes into the making of an “honest” cookbook. I prefer to use the phrase “adapted to suit my own palate or circumstance,” because each one of us brings a particular experience or talent into the kitchen.

I have done my years of entertaining—show-off dinners, as I call them—and I am sure I sent my guests home with a good case of foie. Now I prefer to sit down with a very few good friends—old or new—who understand what eating is all about: that food is an adventure that doesn’t always come off, but that it should always be cooked with love and with the freshest ingredients that the place can offer, no matter how simple. For the more you cook, the less confident you are that things will turn out perfectly—or adequately, perhaps. But then, perfection is rare because it is all tied up with you and the elements, in an unfathomable alchemy that the slightest change in moisture, wind, or phase of the moon can upset. But when it does happen, one has a right to be ecstatic and boastful. A meal prepared with all these elements speaks for itself, transcending barriers of language. What an effective new diplomatic language it could be and, perhaps to some extent, already is.

A former British ambassador in Mexico, Sir Crispin Tickell, loved to relate how the Belgian statesman Paul-Henri Spaak, a well-known gourmet, always said that the most important person in any embassy was the cook; the second, the ambassador’s wife; and only third, the ambassador himself.

Way back in the early 1980s, Frances McCullough, my first editor and still good friend, cajoled me—twisted my arm in her gentle way—into writing this book. I was astonished when she first mentioned it: “Why would anybody want to have my personal recipes?” . . . “Just begin by writing down what you have cooked for me over the years,” she persisted. And so, one day when comparative calm reigned in my somewhat turbulent life, I began making a list—I find most things get achieved by making a list. I began leafing through old books that had recipes printed in faded type, and others written in a dozen different hands. Sometimes the pages were stuck together with a blob of egg yolk, or a squashed raisin, or the unmistakable smear of chocolate—I am sure you know the type of thing—an irreplaceable record of one’s early cooking years. I began thinking about the food I like to eat every day and on special occasions, about the easy recipes for when I am in a hurry and those that I make with unerring regularity. Some were from other people’s books, recipes that I had modified to suit my tastes or to substitute ingredients that I could lay my hands on more easily.

It was quite an experience, rather like opening up a box of old clothes long since forgotten. “Will they still fit?” “Do you think I could get away with that today?” “How on earth did I get by with this one?” There were many surprises, delights, and disappointments. The sight of them began to evoke memories of other times—it seemed like other lives, not mine—and occasions, of journeys, and above all of old friends who had contributed to my culinary knowledge and tastes through the years. Most particularly, it brought back vivid memories of my late husband, Paul. He would collect recipes for me when I couldn’t accompany him on his travels through Central America and the Caribbean. For instance, I found a faded piece of paper with ragged edges typed in his inimitable, terse way: “Sancocho (Dominican National Dish) 2 meats (pork/chicken), (pork/beef), (goat/chicken), etc. Season with garlic, onions, salt. Saute in fat and water, when boiling add yams, yucca, platino verde, potatoes, pumpkin, season salt, black pepper, dash viniger, bouquet garni let simmer, the longer warm the richer.” This was followed by: “Haiti Bouillon: same ingredients less pumpkin, add water cress and small amount spinach (more w/cress than spinach) served with pieces of lemon peel.” His typing was no better than mine, his spelling far worse—like me, he was always in a hurry. My mind wandered back to our last journey together from Mexico to New York when he was fighting against advancing cancer. We were in a motel dining room somewhere in Texas. Paul laid his knife and fork down soon after he had started his meal. “I don’t know whether to thank you or not,” he bellowed. “Most of my life I could eat anything anywhere, but now look what you have done to me. This damned rubbish . . .” With that, he pushed his plate back in disgust.

It was quite a gastronomic adventure searching through those books. I found recipes that I hadn’t cooked for fifteen years or more. I remember they were perfectly clear at the time, but now they seemed vague when I tried to re-create them in my Mexican kitchen. So I began to write letters to friends I hadn’t seen or heard from for years. “Did you really mean two pounds of butter?” “Should the texture be slightly grainy?” “What sort of peppers do they use in your part of Yugoslavia?” “Do you by any chance have Aunt Maud’s recipe for spiced beef?” It seemed like Christmas all over again as letters and cards began to arrive. “That soup was my invention. I do have time to cook, you know [she thought I thought she was too busy being a professional], often to the distress of my family. . . .” “No we ain’t got no recipe for yon ‘spiced beef’ that you believe me mum used to cock up,” came the reply from Scotland. “Lovely to hear from you but I don’t have the slightest recollection of giving you that recipe.” And so on. I found a gazpacho recipe—one out of a hundred that I really like—typed by an old friend and colleague of Paul’s at the New York Times, Sam Brewer. (“Damn good correspondent,” Paul would growl whenever Sam’s name came up.) “This comes from Antonio Olazcoaga, a fine old Basque glutton . . . who was a good friend of Paul’s and mine when we were in Spain together.” Then there was Ruth’s duck-egg sponge, which I had admired on a visit to her house in Cheltenham in the sixties. It was one of those real old-fashioned chewy sponge cakes that you hardly ever find nowadays when “soft and downy” flour and double-acting baking powder, God forbid, are all the rage. I had some difficulty with that one, but I’ll tell you about it later on.

Paul Patrick Kennedy, Mexico City, 1959.

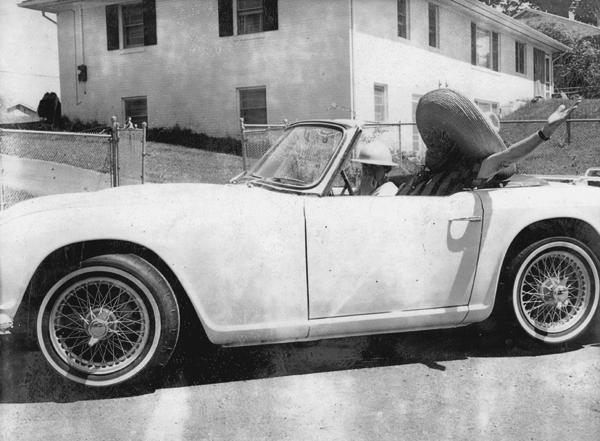

A celebratory Paul and a trepidatious me in a newly acquired Triumph II sports car, 1966. (Having driven in Spain and Mexico for many years, he was happy because he had just passed his US driving test—on his third attempt.)

It was not easy “cooking” this book—especially the recipes that had been so much a part of my life when Paul was still alive—in an ecological house in the mountains of Mexico. There were no cultivated mushrooms—only the glorious wild ones during the rainy season; not one bottle of decent sherry was available, let alone Madeira; there were no pickling cucumbers and no ox tongue. (The local custom here is to barbecue the whole head of the animal, so no amount of money or persuasion could get me a tongue.) I did finally track down some saltpeter, for corning beef, at one of the busiest drugstores in town. “Yes, I do have some,” said the harassed owner, running his hand through his permanently tousled hair, “but I have to look for it, so come back tomorrow.” I got the same answer every day for a week. In despair, I let ten days elapse before returning to the store, and when I finally did go there, he met me with a hurt smile. “Here it is. It has been waiting for you for two weeks. Why didn’t you come in before?”

Building and adapting an ecological house of adobe to suit my needs took years of time and patience . . . in fact, in 1980 I moved into what I now realize was an incomplete shell, and even some of that shell had to be altered and rebuilt. There is no main water supply to the house. All the water that there is, is captured in a large tank during the rainy season, and woe betide anyone who even leaves the tap dripping, let alone open, for more than a few seconds. Hot water to the kitchen is nonexistent, since the solar heater was placed over the guest bathroom, which, though mostly unused, receives a plentiful supply of hot water, while the kitchen is at the end of a lukewarm line. So we have to compromise and heat a zinc tub full of water covered with plastic in the sun to wash the dishes. The three main burners of the large masonry hacienda-type stove were, until recently—and for most of the cooking for this book—optimistically connected to the methane gas supply from the digester under the cow shed. The cows do their part magnificently, but the pressure, design, or something is wrong, so no gas.

For the first two and a half years of occupying the house, I had no refrigerator and no car to go and get last-minute supplies, and to make things worse, Zita the cat filled herself up during the daytime with forbidden fish from the aquaculture tank and slept at night while the mice were at play. It was not easy, and I thought longingly of the places where I had test-cooked some of these recipes: Peter Kump’s compact and alphabetically ordered kitchen in New York, or Jerrie Strom’s kitchen with its magnificent array of stoves, pots, and counters, with a pair of efficient Mexican hands to make the dirty dishes disappear as fast as they were used.

I did have a small electric oven, but an erratic supply of electricity because the bad storms that year kept hitting the power line—just at the time, of course, when there was hardly a breath of wind and my air generator was sluggish.

“How lucky you are to lead such a peaceful life in the country!” (when I am not living and touring in the United States, of course) is a general comment from unsuspecting friends and acquaintances. I usually nod in agreement because it is easier to agree than to go into all the reasons why it isn’t.

For instance, I am just beating up the egg whites for a soufflé when my neighbor Don Zenón yells from the gate, which is a good hundred yards downhill—it is the only way of communicating because he and my large dog, Guardian, do not get along. I have to go down and find out what he wants. It turns out to be a contribution to the local fiesta. I give him all the reasons why I don’t approve of the debauchery and filth that go along with it, but ten minutes later when he leaves I find that I have agreed to contribute a considerable amount of men’s clothing to put on top of the greasy pole that the young bloods will attempt to climb. Back in the kitchen once more, I realize to my horror that I am contributing generously to the machos of the village—not one of the girls I could think of would be caught dead climbing up a greasy pole. Too late! He has gone, and the eggs have fallen flat beyond resurrection.

On another occasion, the dough for the hot cross buns had just risen to perfection for baking when Elisorio, the general factotum at Quinta Diana, as it has come to be known, came to report that the male goat was frothing at the mouth and running around in circles. This obviously required immediate action, so off I went to find the vet—to this day there is dried dough on the steering wheel—leaving my beautifully risen buns to their own devices.

Interruptions of this sort prompted me to change my cooking time to the late afternoon and evening, when everyone had gone home and it was relatively quiet. But I hadn’t taken into account that the afternoon storms during the rainy season might cause a cut in the electricity. They always came in from the east, however, and I could see them from the kitchen window. Of course, one day I was fooled. The coffee sponge had had twelve minutes in the oven when the lights went out—a storm had blown in unseen from the north. I watched anxiously with a flashlight as the cake that had risen to the top of the pan held . . . I prayed to the Tenth Muse . . . and it held there serenely until the lightning passed and the oven whirred into life again.

Later that week I made the mistake of putting the newly candied citron out in the sun to dry. About an hour later, I heard a shout and smelled smoke. There were Elisorio and his son fanning a small bonfire into life. The bees had swarmed in their thousands all over the peel, and he was trying to convince them to go back to their hives.

One night, I forget what I was making, but I had all the appliances going full blast when everything went dark, including the light over the front door by the fuse box. I found a new fuse easily enough, and with a small flashlight between my teeth, I pulled the lever down to disconnect the incoming current. Just in time the warning of Marcemio, Elisorio’s oldest son, flashed into my mind: “But that still doesn’t disconnect the current from the windmill,” he had told me. Obviously what I needed was a rubber glove, so I went upstairs to find one. I stopped dead in my tracks, for there above my desk was the largest deadly scorpion I had ever seen. The fuse was forgotten. Where was the spray?—the only nonecological permitted in the house, because I refuse to admit fleas and scorpions into my ecological cycle. I went down to the kitchen and groped around for the spray. Of course the scorpion had gone when I got back, but I doused the area thoroughly anyway. Now for the rubber glove—I had almost forgotten it. Down I went again and tugged and tugged at the fuse capsule, which refused to budge, and since I believe in signs, I gave up. This obviously was not my night to cook. I left the mess of doughs, pots and pans, and greasy spoons, and went off to bed.

And this was just the beginning of what would become my Mexican Cooking Center.

My Mexican Land, My Kitchen

As I sit down at my computer to begin these notes for the revised edition of Nothing Fancy, it is again November, but thirty years after this book’s original publication. No longer can I see the mountains from my desk; the view is blocked by the towering pine trees that I have planted over the past thirty-four years. When I moved in, in February 1980, the land in front of the house was covered with withering cornstalks that had been drying since the late autumn heat. Now the house is almost hidden behind banana plants—belying the semitropical climate—towering over the citrus bushes (limes, sweet and bitter oranges, and tangerines) and passion-fruit vines.

The entrance to Quinta Diana today. Photo by Michael Calderwood.

It is early in the month, and October weather is still with us, that glorious month as the rains begin to retreat to a drizzle, leaving the countryside a kaleidoscope of greens dotted with the colors of the autumn flowers: yellow, orange, pink, and white. It is harvest time for the bees, with their audible buzz, while multicolored butterflies dance along the fields and hedgerows. The aloe vera is in flower, and the slender flowers of the night-scented jasmine perfume the house. Even the sour pomegranate has decided to show off its brilliant red flowers for a second time. It is such a magical time in the altiplano, the highlands of Mexico.

The early, heavier rains have encouraged more green berries to form on the coffee bushes, and the citrus bushes are in bloom again, with a second harvest of fruit still firm and green on their boughs. The time is almost here to burrow in the soil around the chayote vines to loosen and take out the delicious bulbous roots, chinchayotes. Only a few wild mushrooms gathered in the nearby mountain forests can still be found, sold by the street vendors outside the marketplace, with an occasional basket topped with morels. Now the guavas are prodigious and at their best, so it is time to make ates (fruit pastes), while both the sweet and bitter oranges are just about ready to make my English marmalade: sweetmeats to last for the coming year. The newly planted wheat is sprouting while the ears of corn are maturing to be harvested next month. The first mature pumpkins are ready, the mameyes are here from Tabasco with their deep-red flesh tasting of almonds, and local avocados abound.

To most visitors my kitchen is perhaps a mess, but to me it is a lively witness to work-in-process. Hanging up beside the large wok are branches of drying avocado leaves followed by a series of baskets. Below, in a row along the window, is a line of recycled, decorative tequila bottles containing a variety of dark-colored earthy homemade vinegars: several years of pineapple, alongside banana, pulque, and the more prosaic red and white wine. The newly laid eggs are dated and stuck vertically—to keep the yolks in the center—in small baskets full of coffee beans to stabilize them.

The hanging baskets—themselves remarkable for their shapes and intricately woven patterns—store herbal teas, exotic teas in glamorous packages from London’s Rare Tea Lady, dried chiles from many regions that have seen their best days, and ates of guava and quince from the year before with a dried, sugary surface. On the crowded counter there is a tall copper pan holding natural sugar piloncillos and panelas (named for their flat, round forms), gathered in my travels from rustic trapiches that grind the newly cut sugarcanes.

A fine selection of vinegars. Photo by Michael Calderwood.

A well-stocked pantry is a must. Photo by Michael Calderwood.

The alacena (see photo, above) built into the back wall of the kitchen holds the “treasures” of the house, gathered through my many years of travel throughout Mexico, some even from my first years in the late fifties and early sixties: highly glazed and delicately patterned baked-clay cazuelas, ollas, pinchanchas, jugs of all sizes, and decorative flasks (to carry drinks to the fields). Below them sit molcajetes, volcanic rock grinding bowls of different sizes and centuries. Sitting on the floor is a series of heavy earthenware containers for storing sugar and a variety of flours, raw coffee beans, and wheat grains.

And then there is the pantry, a storage cupboard par excellence. God forbid that I should have a yen for an Indian dish and not find the turmeric, fenugreek, and culeb berries there waiting for me. Of course, there are many odd specialties: dried shrimps of all sizes, whole pumpkin seeds from every region, and a plethora of dried “oreganos” from all over Mexico. There is a jar of small nuts, piñoncillos, used for pipián-like dishes of the Sierra Oriente (these little nuts are poisonous if not well toasted first). There are others with lumps of rustic chocolate, pieces of raw chicle . . . It is a bewildering, fascinating, and exasperating adventure to take even a cursory look, let alone search for something in a hurry.

The refrigerator is not much better—it is messy, and nobody else is allowed to peer inside. I am sure you all know that when cooking for one, there are always leftovers: bits and pieces of food—some of it delectable—saved for a day or two or three, just in case. Some of the time my fridge has an intriguing aroma.

Tucked at the back of my cooking “peninsula” (because the counter-like construction is connected to the rocks) there are antique bateas, long, narrow wooden troughs, piled high with either vegetables—potatoes, carrots, onions, and green chiles—or fruit from the garden—oranges, limes, and tangerines, along with papaya, pineapple, grapefruits, and whatever else is in season at the local market. At this moment, they are also topped up with passion fruit, tree “tomatoes,” and avocados from the land around the house.

Stored away in the basement freezer are containers of cooked cuitlacoche, cubes of homemade chicken broth, and a syrup of sour pomegranates for aguas frescas. Of course, alongside a few duck breasts there are two sizable lumps of duck liver—now, let’s face it, life without a feed or two of foie is sadly lacking.

We do have lists: one for the freezer in the basement, another for the fridge and freezer in the kitchen, and yet another for the dried chiles. There is yet another one for last year’s crops: kilos of wheat grains, kilos of dried corn, kilos of coffee beans—all noted in Sherwin’s decorative handwriting. I always forgot what was stashed away, but now I know how much of my homemade whole wheat bread is left; whether there is still some mole poblano from last year; and I hope there is a container or two of wild blackberry atole at least six months old alongside my very favorite fava-bean soup. That poor overloaded machine is stuffed to the gills with dried chiles that would otherwise become moldy. Hidden underneath is a very large duck that has been sitting there for two years; obviously, it is time to make some rillettes à la Paula Wolfert.

My kitchen will never be tidy. There is the dog’s bed, the dog food. There are lots of little doggie-proof gates. Of course there is a flyswat and lots of cheesecloth to cover everything, for straining, or for wrapping the cheese. The hot pads are on their last legs and stained by the ash from the wood-fired oven outside on the terrace.

Every gardener, wife of a gardener, and cook of a gardener knows that you are actually a slave to your garden. Everything is ready for cutting at the same time; most plants get frostbite while the root vegetables rejoice because this is their tonic. Just as you want to snip your favorite herb it is wilting while, darn it, the rest are flourishing.

A DK Day

As an author of cookbooks and, I suppose, something of an anachronistic character in the world of food, I get requests for interviews. First I say, “You should come and see how I live; that will give you most of what you need to know.” But if they don’t come, that predictable question is asked, the one I can’t stand: “How does DK begin her day?”

Well, it’s sort of boring: after some 40 minutes of muscle stretching, it is time for breakfast. Breakfast is the most conservative meal of the day—after all, you don’t want to tickle your palate with toasted grasshoppers or even a “light” vindaloo. This is going to sound rather smug, but . . . it has to be tea, real English tea with milk, cold whole milk (none of that blue stuff for me). Sometimes a little bowl of oatmeal, with home-produced honey, and again, whole milk with a dab or two of cream. I love thick, raw cream, fresh or soured. Alas, it does not have the golden hue of cream from a Jersey or Guernsey cow—a relic of my English upbringing—but none of that commercially false half-and-half, thank you. This is followed by toasted, tough whole wheat bread: homemade from start to finish with flour from the small amount of winnowed, sifted, and stone-ground wheat grown on my land. Of course I eat it with lots of butter and bitter-orange marmalade that I make twice a year from oranges gathered from my own trees. The marmalade is dark, dark orange in color and thick, almost solid, with its coarse-cut peel. That’s it, and I told you it would be boring.

And that’s it, day after day, when I am at home. But, I may hastily add, this all changes when I start to drive somewhere or other to track down a recipe or an elusive chile. Setting out at sunup, “en ayunas” (on an empty stomach), I try and plan to stop at 10:30 a.m. at my favorite rustic restaurant for that most savory of Mexican meals, el almuerzo (akin to brunch). I take a small metal filter pot filled with my own coffee, order boiling water and hot milk (leche bronca, raw cow’s milk), and drink it accompanied by a yeasty local pan dulce. I can hear the rhythmic patting out of a tortilla as I order frijoles de olla (soupy beans) and eggs scrambled with the local chorizo or whatever else they offer. I like my fruit last, and it comes cut into large chunks. In one of my favorite eating places en route to Oaxaca, for instance, the fruit is invariably papaya, ripened and cut from the trees growing on the adjacent land. Perhaps I am biased, but this Mexican repast beats most breakfasts anywhere. I no longer yearn for that most English of breakfasts, a very hearty meal in itself: thickly sliced undercooked delicious bacon, real pork sausages, fried eggs, a broiled tomato, a large field mushroom, and fried sliced potatoes. If you are lucky, there will also be a halved lamb kidney.

Then the next predictable question: “What is a normal day for DK?” I try not to laugh. Nothing is normal around Quinta Diana. My thoughts are interrupted by one of my helpers, Benito: “Look! Here is the culprit who has been digging up the roots,” and there, hanging from his arm, is a huge armadillo. I know we shouldn’t decimate the wildlife, but I refuse to share my veggies. Besides, Benito’s family is the only one around who will cook and eat the armadillo, first removing the shell and then the numerous glands that would give the otherwise succulent flesh, as they say, a “fishy” taste.

I get the news that one of our young chicks has been picked off by a foraging falcon, and a deadly coral snake has decided to hide in the stone walls of the chicken run. And then Consuelo brings me my favorite Issey Miyake coat and shows me the half-eaten collar; some adventurous mouse has dived under the plastic covers and . . . On those days, I can’t help thinking of an article I read years ago, an interview with a distinguished British lady living in the country. The interviewer had intimated that life there was perhaps rather boring for her, away from the social life in London. “What do you mean, young man?” she said. “All the great dramas take place in the country.” Ah yes, I sigh. . . .

When I hear the dogs barking frantically (they are not allowed to do so under normal circumstances), I am told that the neighbor’s cows have jumped the fence and are munching on the new cornstalks. Now, this requires urgent action. Or there is the mass buzzing of swarming bees almost overhead. I hear someone in action below and see Carlos retrieving, and setting down on the spare land, an almost-forgotten beehive, and lo and behold, a miracle: the bees decide to take shelter and, voilà, we have another full, active hive!

There is many a day when I have just settled down to the computer to write, when I am reminded that we need corn for the chickens (not so easy because I insist on a local corn, and not GM or hybrid) and also a sack of cement and padlocks for the new protective gates. And not to forget the bones and carrots for the dogs. So off I go shopping in my trusty fifteen-year-old truck, taking the opportunity to pick up the long-outdated mail from the sullen young man at the post office and almost forgetting to pick up the stamped sheets of wax for the beehives to prepare for the forthcoming honey harvest. I return, exhausted, and that’s when I dream of a two-star restaurant next door. But in its absence, my constant and consoling companion is my satellite radio, which whisks me from the gorgeous music programs produced in Chicago and Los Angeles to the sobering BBC newscasts and scientific discoveries. Saturday is my Scotch night—just a jigger on ice with a very little water—and it doesn’t have to be single malt. I’m happy with Johnny Walker’s Green Label or a plebeian Cutty Sark or Teacher’s.

And of course it all begins again in spring. In March or thereabouts, the first picking of the coffee berries takes place—they never ripen all at the same time on the bush. Then the little machine for crushing—which I acquired in the coffee-growing area around Coatepec in the state of Veracruz—is brought out from storage and cleaned. Crushing the red-skinned outer flesh, “the cherry” around the berries, is hard work, as the handle is heavy and stiff. They emit a delicious, fruity aroma. The flesh is composted, while the beans, covered with a grayish, mucilaginous coating, go into a container in the greenhouse to start the fermentation. This can take up to four days, depending on the temperature. I was told at a coffee finca in Chiapas that when you stick a finger down into the mass and the hole does not close up (totally unscientific, of course), the coffee beans are ready to be washed and then dried in the sun.

And then there is the wheat to be harvested in early summer. The field of ripening wheat is a buzz of activity as the sharecropping birds ignore the scarecrows and little colored whirlies and feast on the swelling grains.

Looking Ahead

“So what now?! Another book?” everybody asks. I doubt it. I think my role is to help those who have requested it, help in putting together books on the lesser-known Mexican regional foods that have not yet seen the light of day. And to continue, of course . . .

Lately, my time has been consumed by working with botanists from the Instituto de Biología of the National Autonomous University to pull together my lifetime of research work to be preserved on a personal page included on the website of CONABIO, Mexico’s Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Apart from being a great honor, it also gives me enormous satisfaction to know that my records, including notebooks and photographs detailing what I have found from not only a gastronomical but also a botanical, social, and ecological point of view, will be available to all.

Another absorbing project has been the establishment (about to be completed) of a foundation: The DK Project. This plan has been enthusiastically endorsed by many younger Mexicans, among others, to ensure that what I have created at Quinta Diana will be preserved, so that my work, ideas, research papers, photographs, and culinary (including botanical) library will stay intact for future researchers. I would hope that along with preserving these physical resources, my strong ideas on the organic cultivation of foods (indisputably linked to our care of the environment); the reduction of nonorganic waste; and sounding the alert about the ways in which the food industry, IN ALL ITS FORMS, is poisoning our land and landfills (which will ultimately leak chemicals into our water sources and those of future generations), will also be heard, heeded, and acted upon, since, sadly, the last is already happening.

In preserving Quinta Diana, it’s also my hope that one day, decades from today, someone will decide to bake a fine cake in my magical solar oven on the terrace, and serve it with a cup of the especially delicious Quinta Diana coffee—in other words, that the sheer pleasure of the place endures as well.

I hope that decades from now it won’t be necessary to harangue people about keeping a green kitchen. The struggle has been going on for a long time. At least twenty years ago, the late Charlie Trotter kept an immaculate green kitchen in his eponymous restaurant in Chicago. Of course, the media didn’t pick up on it—I can only assume it wasn’t of any interest. The talented young chef Christopher Kump, son of Peter Kump—founder of the James Beard Foundation—kept a green kitchen in his Café Beaujolais restaurant in northern California. And Dan Barber of Stone Barns gave us all a genuine surprise when he devised a week of trash dinners at his New York restaurant Blue Hill, each one executed by a well-known chef and imaginatively concocted of throwaway ingredients that would otherwise have gone into the bin. I’m sure there are others, and that they will begin to emerge now that the subject has aired. The New York Times and others have written about this subject, but in a mild way that didn’t catch the attention of the greater culinary world.

Recycle and reuse—in every way you can.

Fortunately, there are choices to be made NOW in purchasing, using, and promoting “green” products. Look into your own garbage bin and think about the responsibility that not only you have, but every one of us has, to ensure that future generations can live on a healthy planet. Yes, we all want to have delicious food—and I think you will find plenty of it in this book—but it’s urgently important to recognize that great food depends on a living, breathing, cared-for planet.

This is my cri de coeur that has animated all my presentations, particularly at international culinary events like the MAD Symposium in Copenhagen in 2013. It’s up to you now—act and pass it on!

DIANA KENNEDY

SAN PANCHO