CHAPTER 2

The Loss Is Great, the Confusion Greater

THE TRAIN BEARING THE 4TH MICHIGAN ROLLED INTO TOLEDO BETWEEN NOON and 1:00 P.M. Dr. Chamberlain said there was “a great crowd of people to receive us.” After a pause of two or three hours, the regiment boarded two eastbound trains, arriving in Cleveland that evening for “supper and some good hot coffee,” wrote a man who initialed his dispatch “W.” The soldier noted that “we were cheered at every station and bid God speed by everyone.” Sgt. Eli Starr of Company C described the trip as “one continuous ovation” with women and children throwing flowers; other accounts told of people waving flags and bringing “eatables,” pitchers of water, and bouquets to the soldiers at points where the train stopped for water and wood. The men were well fed in part because the regiment's quartermaster, Henry A. Grannis, traveled ahead to make the arrangements.1

Orvey S. Barrett, a Lenawee County man who was then 26 and a sergeant in Company B, remembered that Cleveland was where he was first issued his “hardtack,” the infamous thick, unleavened bread or cracker that soldiers came to joke about and depend upon. “They were round,” he wrote, “and as large as an elephant's foot, and as tough as a prohibitionist's conscience.” Barrett said some of the men, awestruck by the seemingly indestructible crackers, stood on the platforms of the cars, seeing how far they could sail them, while others were “trying to pulverize them” with coupling pins. The musicians of the Hecker Band from Cleveland probably had a better time, since they were allowed off the train for about three hours to visit friends and family.2

The 4th Michigan transferred to another eastbound train that night and left for Erie, Pennsylvania, driving on through the early morning hours of June 26. Sgt. John Bancroft of Company I wrote that the citizens of Erie gave the men coffee and cake and other treats. The correspondent who signed his dispatches to the Detroit Free Press “Hamilton” wrote that the citizens waited all night for the regiment's arrival, which came about 4:00 A.M. Then the train continued along the Lake Erie coast another 45 miles or so, crossing the state line into New York. “At Dunkirk stopped and went to Lake Erie to bathe,” Bancroft noted. “This was a great treat indeed.” A soldier who attracted the concern of a Dunkirk woman seems to have been John B. Warren, 40, of Company H, who had been injured in Adrian the day before when a heavy trunk fell on him as the train was being loaded, badly bruising his leg. The Dunkirk Union reported that the lady saw a limping Michigan soldier, led him to her home, and bandaged the injury. The soldier was visibly moved, the journal noted, telling her, “You done it just as my sister would.”3

The men changed trains at Dunkirk, boarding the New York & Erie Railroad that morning. It took them southeast across New York to the town of Olean, to Hornellville, and on east to Elmira near the Pennsylvania state line. Citizens continued to bring them coffee and snacks at their brief stops before they arrived for several hours rest at about three-thirty in the afternoon. Many Michigan families came from the state of New York, and the diaries and letters of some soldiers mention that they saw old friends, neighbors, and relatives along the way. The regiment left the cars and marched to the camp of the 23rd New York and “partook of a hearty supper prepared by the ladies of Elmyra,” wrote “W.” At 11:30 P.M., the 4th Michigan boarded freight cars of a train taking them south. The men thought it funny that they were loaded onto cars used for livestock; James H. Cole, the captain of Company B, remembered that the soldiers brayed, neighed, barked, mooed, crowed, oinked, cackled, and meowed as the train pulled out. Orvey Barrett wrote that some pranksters pulled a coupling pin and detached three or four cars until officers got the train backed up and reconnected them.

The men tried to sleep as the train clattered through the Susquehanna Mountains. Now it was June 27, and there were two or three more stops before they reached Pennsylvania's capital. At Williamsport the men left the freight cars for more comfortable passenger cars, and again women from the town came through the train with food and water. As the train rolled on, a soldier named John Rouse of Company K suffered a head injury when he fell from a platform. He was left behind and worked on by a surgeon, and caught up with his regiment after a brief recuperation. By mid-afternoon of the 27th, the train carrying the 4th Michigan reached Harrisburg.4

The regiment got a respite from traveling and Sgt. Eli Starr was relieved they were done with the longest part of their trek. “I haven't slept two hours since starting, being on guard all the time day & night,” he complained. “This was for the purpose of seeing that not a man was left at any station.” The regiment was issued more equipment, first tents and then muskets. Shortly after they got off the train at Harrisburg, according to John Bancroft, “We got tents and set ourselves to work to set them, and then have a chance to wash in the canal. We got coffee, etc. late in the evening.” The place was called Camp Cameron, a temporary stopping point set up for Union soldiers headed for Washington, D.C. As did many, Sgt. Jonas Richardson went for a walk the next day with his friend Jim Clark. He declared the state capitol “the handsomest place I think that I ever saw.”5

For the first time, many of the soldiers of the regiment cooked for themselves. Sergeant Bancroft expressed confidence. “We are now ready for a soldiers life, fare and privations,” he wrote. “Rations of salt pork and ham, Hard biscuit are given out once a day and coffee twice.” The 4th Michigan's assistant surgeon wasn't so sure the men were ready to cook their own food since so many of them had been fed by their mothers, wives, and sisters. “It is a little amusing to see the boys cooking their ‘grub,’” Dr. Chamberlain wrote. “It is dealt out to them in the crude state, except bread.” The doctor admitted he had an easier time, since he and the regiment's surgeon, Dr. Joseph Tunnicliff Jr., “messed”—made their eating arrangements—together. Doctors had to pay for their own food, so Tunnicliff hired an aide or servant named John Livermore who'd spent several years in the Rocky Mountains and was familiar with camp life and cooking. The doctors and their helpers were able to “get up a first rate meal,” Chamberlain wrote.6

Muskets for the men arrived in boxes. Orvey Barrett described them as “old buck and ball” weapons, while Jim Tuttle called them “old-fashioned flintlock muskets transformed into [percussion] cap locks.” The soldier who signed his letters “W” wrote that they were “very much disappointed” with these old weapons, since they thought they were getting Enfield rifles, far better, more accurate firearms. Some reports said Col. Woodbury was angry that his men had again been issued outdated weapons, but that Secretary of War Simon Cameron assured him via telegraph that the regiment's use of these muskets was strictly temporary and they would get better firearms when they reached Washington. With the regiment in camp for the last two days in June, officers ordered the resumption of drill with the expectation that they might face mobs and street fighting with Confederate sympathizers in Baltimore. On July 1, the men were awakened at 4:00 A.M., struck their tents, had breakfast, and again boarded cattle cars. The train stopped at York, and Sergeant Bancroft had a close call when it started without him. He managed to catch up and cling to some part of a car, perhaps a ladder or a rear platform. “Rode across a bridge some 200 ft. in length, hanging by my arms,” he noted. Whether he climbed to safety or was pulled in by comrades, he made it aboard.7

The train crossed into Maryland and slowed to a halt several miles outside of Baltimore. The regiment debarked, formed up, loaded their weapons, and marched to the depot for the rail line to Washington. Back in April when the first Union volunteers were on their way to Washington, there had been a riot by a secessionist mob as they passed through Baltimore. A number of soldiers from that regiment, the 6th Massachusetts Infantry, and civilians were killed in the disturbance. Rumors swirled that other Union troops moving through the city would be attacked. Sgt. Thomas Jones of Company B wrote that “the Colonel [Woodbury] says he will have us burn the town if they try to stop us.” Now crowds watched the troops march through and there was indeed at least one Confederate sympathizer who wanted trouble. This “crank of a Rebel” pointed a revolver at the regiment's flag bearer, Orvey Barrett said. As a “file-closer”—a soldier responsible for keeping gaps from forming in the ranks—Barrett was at the rear of that particular platoon and in a position to see the gunman. Barrett claimed he raised his musket at the secessionist “in less time than it would take to pull a trigger.” But the Detroit correspondent “Hamilton” said the gunman was knocked down and subdued by law officers before the Michigan soldiers could react. Eli Starr and Dr. Chamberlain gave similar accounts of the incident. “Had that pistol been discharged, the result would have been a terrible indiscriminate slaughter,” Barrett wrote. “W.,” the 4th Michigan soldier writing to the Detroit Free Press, didn't see this incident. He wrote that the people of Baltimore had been “perfectly kind” to the 4th Michigan. Apparently jeered and cheered by the crowd—there were reports of both—the regiment marched on to the depot for another train and boarded the cars that evening as rain began to fall.8

Jim Tuttle of Company F remembered that because the men didn't yet have cartridge boxes for their ammunition or scabbards for their bayonets, the soldiers put their bullets and powder charges in their pockets and hooked their bayonets over the barrels of their muskets, but in a reverse position so the long blades didn't poke into the ceiling of the railcars. But bayonets weren't designed to be put on this way, so part of the upside down-mounted blades protruded over the business end of the muskets, Tuttle wrote. This would prove embarrassing for some of the new soldiers. At a point called the Relay House or “Halfway House” on the trip to Washington, D.C., the regiment again stopped to change trains. Again the rumor swept through the 4th Michigan that they were going to be attacked by Confederate guerillas. Jim Tuttle later claimed that as the men waited to get out, some excited Union soldiers ran up to the train, glad to see the arrival of more Northern troops; some of them fired revolvers in the air in a celebratory salute. “Our boys supposing they were guerillas blazed away and ‘buck and ball’ went flying fast and furious for a few seconds when the officers succeeded in stopping the firing,” Tuttle wrote. Since the men had hooked their bayonets upside down on their muskets, these also went flying, he insisted. “No one wanted to admit they had fired, but every man that fired a shot had blown his bayonet away, so they were easily detected,” Tuttle claimed. A news account by “Hamilton” stated that Massachusetts soldiers ran up and cheered the 4th Michigan as its train rumbled by. He wrote that some of the Michigan men fired into the air in return. Orvey Barrett didn't write of these particulars, saying only that the report of a Rebel attack at the Relay House “was a false alarm.”9

A hard rain kept falling as the men boarded cars for the final miles from the Relay Station to Washington, where they arrived after midnight on the morning of July 2. An officer met the regiment and led them through quiet city streets to a large, empty brick building on Pennsylvania Avenue, where the men slept on the floor, using their knapsacks for pillows. Later that morning the men ate a late breakfast of hard crackers and cheese and marched in the afternoon to the city's arsenal, where they were issued slightly better muskets, and then returned to their temporary quarters for the night. The regiment marched to Meridian Hill on July 3, the grounds of a mansion once occupied by ex-president John Quincy Adams, less than two miles northwest of Washington's center. Here they set up their new camp. “From our elevated position we can see moving hither and thither tens of thousands of soldiers and on every hand the landscape is dotted with tents,” wrote Lt. Richard DePuy of Ann Arbor. They called the place Camp Mansfield after a Union general. Some of the regiment's men complained they hadn't been properly supplied with provisions since they'd left for Washington. Sgt. Eli Starr said there was a kind of protest about the food shortage by Company C on the night of July 5, but the men settled down after being admonished by Colonel Woodbury. James Spence of Company E groused that “provisions have been short ever since we left Adrian,” but he admitted that within a few days after arriving at Meridian Hill they had “received better fare with the promise of that improving.”10

Union artillery roared to mark the Fourth of July and the men saw President Abraham Lincoln, General Winfield Scott, Secretary of State William Seward, and other VIPs when a review was held. Sergeant Bancroft heard a rumor that Scott “said today that those of us who were living”—presumably after a great battle or campaign against the Confederacy—“would dine at home at Christmas.” Their camp on Meridian Hill was close enough to the White House that Lemuel Allen of Company G told his family that “with a spy glass we can see the president sometimes standing in the door” about a mile-and-a-half away.” Not long afterward Allen toured the White House and other buildings “and had the honor of shaking hands with ‘HONEST OLD ABE,’” he wrote. Stranger still was that two of his comrades from Company G, Harrison Daniels and William C. Pierson, got passes and strolled down to the White House when they were excused for duty because they were sick. “After being admitted, we were shown a waiting room,” Daniels later wrote. “Presently a door opened and President Lincoln entered, followed by his cabinet and others of military rank.” Daniels thought the president “truly the homeliest man that I had ever seen,” but Lincoln warmly greeted him and Pierson when they rose and saluted him. Hundreds of other soldiers from the 4th Michigan and other regiments also went to town and took in the sights—the White House, the Washington Monument, the Patent Office, the museums. “I could not tell everything we seen if I should write a month,” wrote Charles H. Barlow, a Livingston County man in Company K. But now that he'd traveled across several states to Virginia, Barlow came to some conclusions about his Wolverine State. “I like Michigan better than all…not that I am homesick, far from it. But it looks like the air seems cooler, freer & the girls are better looking,” he wrote.11

The weather was mild for July, though as the month wore on there were days of more typical summer heat. The men enjoyed reasonably good health, given 19th-century medicine and health practices—only one man had died of illness while the regiment was in Adrian, with another dying there shortly after they left. But now they began to experience more sickness. Soon a 43-year-old man from St. Joseph County, Alexus B. Parsons, died of illness. Dr. Chamberlain said that some of the men's common affliction was their own fault. “Almost all are trouble more or less with the Diarrhaea,” he wrote, “but they are very imprudent in eating a great deal of fruit…. The water is soft, which is good enough after we get used to it.”12 Of course, many soldiers, North and South, suffered and died from typhoid fever and dysentery, not because of eating too much fruit but because of contaminated drinking water, poor hygiene, and bad food. Those who survived it or could afford to joke about diarrhea sometimes called it “the Virginia two-step,” but disease would take more lives during the Civil War than battle.

The regiment resumed drilling, but the question of what lay ahead for this new and growing Union army was on many minds. “General Scott is old and feeble,” wrote Washington W. Carpenter, one of the Indiana men in Company B. “I do not believe Lincoln knows Scott's policy. He has seventy-five thousand men in and around Washington that he can bring into line of battle in two hours.” Carpenter seemed disgusted that Virginian secessionists fired at Union pickets and were not made to pay for these attacks, but he'd heard rumors that the Union army would soon be moving south against Confederate positions at Fairfax. “There will undoubtedly be some fun there,” he wrote with the bravado of a soldier who hadn't yet been in combat. Dr. Chamberlain, though presumably more sophisticated in understanding what would happen to men hit by flying lead, echoed the men's naive enthusiasm for battle. “We have just received orders to pack our traps to move to Alexandria [Va.] in the morning,” he wrote on July 13, referring to the town that served as a jumping-off point from Washington to Virginia. “The boys are elated with the idea of getting where there is a chance for some fun.” His notion about war as “fun” would soon change.13

For the next few days thousands of Union troops were on the move, some boarding steamers on the Potomac River for transport to Alexandria. This army was under the commander of Brig. Gen. Irwin McDowell. The 4th Michigan was part of its Third Division, commanded by Col. Samuel P. Heintzelman. Specifically, they served in this division's Second Brigade under Col. Orlando Willcox, a native Detroiter and West Point graduate. Willcox's first Civil War command, the 90-day 1st Michigan Infantry, served in this brigade, as did two New York regiments.14

The 4th Michigan moved from Meridian Hill on July 14, marching through Washington's cheering crowds to the Potomac wharfs and the waiting steamships. It was a short trip to Alexandria and they arrived in the early afternoon. Sgt. Eli Starr said the soldiers removed their hats and caps as they marched by the house where Colonel Ellsworth had been shot and killed. Then they continued into the countryside to Cloud's Mill in Virginia's Fairfax County. “When we arrived our tents had not come, so we went to picking blackberries, there being plenty on the ground where we were to be quartered,” wrote Henry L. Case of Hillsdale County. “It was funny to see the boys stooping over picking, for they were on low bushes or vines.” Dr. Chamberlain said this area was “the heart of the enemy's country,” with many abandoned houses.

The regiment was here briefly, marching west with their division on July 16. The Second Brigade was ordered to nearby Fairfax Station. They were instructed to leave behind their tents, each man taking only a blanket and hardtack along with his weapon and ammunition. But men did not live by hardtack alone. George Young of Company B said that the soldiers quickly learned “a trick” from the 11th New York, a regiment of “Fire Zouaves”—to raid the local Virginia farms for livestock and produce, a practice soldiers euphemistically called “foraging.” “The boys are coming in with hogs, geese, chickens, fresh bacon, sugar rice and flour, find them secreted in the woods,” he reported. But the night was cold and damp and the men had only blankets or overcoats for shelter. “The boys begin to think this was campaigning in earnest,” Dr. Chamberlain wrote. He came up with some historical booty when one of the raiding Zouaves threw away a portrait of George Washington taken from a Virginia plantation. The doctor packed it up and sent it home.15

Their brigade moved out the next morning and soon came across felled trees and debris across the road and nearby railroad tracks—obstacles left by the Confederates to block their way. But they reached abandoned Rebel trenches, capturing a few enemy troops in the process. At the order of their division commander, four companies of the 4th Michigan under Major Childs remained to guard the train depot at Fairfax Station while the rest of the regiment proceeded to Fairfax Court House. The men watched as thousands of Union soldiers, cavalry, and artillery marched on to the southwest toward Manassas Junction and the Confederate positions. But at Fairfax Station, the men continued pilfering nearby farms for food. “As soon as they boys had stacked arms the chickens & pigs (rather numerous) had to suffer,” wrote Lt. George Monteith of Company G. Orvey Barrett tried to kill an old sow, but six shots from his small-caliber pistol had no effect on the animal. However, Washington W. Carpenter, the smallest man in Company B, easily dispatched a pig with a shot from an old Colt revolver.

On the morning of July 18 and on into the next day, the soldiers heard cannonading in the distance. The fact that they weren't at the scene of this fighting, preliminaries for what would be called battle of Bull Run, was disappointing. “Our company, B, is detailed to stay out,” complained George E. Young, one of the Indiana men. “I do not like that.” Some were put to work clearing the rail line of trees and piles of earth left by Rebels, while some guarded the railroad depot and others acted as a reserve at Fairfax Court House.16 Jim Tuttle of Company F got in trouble when he had “a little argument” with company officers, Capt. Sam DeGolyer and Lt. Simon B. Preston, on the morning of July 20. Unfortunately for him, since his part of the regiment was then posted at Fairfax Court House, the officers had a jail cell at their disposal. Tuttle was locked up. “I had not yet got the hang of strict military discipline,” he admitted later. Now he faced court-martial, for he had, by his own words, “talked pretty bad to the Captain.”17

Sunday, July 21, dawned clear and mild and again cannon pounded in the distance. “Today the guns are firing at Bulls Run in the direction of Manassas Gap,” Sergeant Bancroft wrote. “The firing has been going on for two hours.” He realized that men were fighting and dying. Later he noted, “All day long we have listened to the guns.” Sgt. William Limbarker, 26, of Company F, also wrote in his diary as the hours passed. “It's a pleasant day,” he wrote; “the Cannonading commenced this morning at half past Nine o'Clock this morning and be[e]n heavy very heavy all day up to fore.”

Bull Run

It was frustrating to hear the battle but not be able to pitch in, wrote Charles Barlow of Company K. “I tell you Charley you don't know how it makes one feel to get as news as that (7 miles to a battle) & then be tied up. but we had to obey orders & could not help our boys in the fight.”18 Dr. Chamberlain was taking care of sick men at Fairfax Station as soldiers from the 4th Michigan finished clearing the railroad tracks, allowing Union troops to be brought up by train. “It was lively times all day at the Station,” the doctor said. “Couriers were arriving hourly from the field with dispatches for Headquarters, and to hurry up the reserve.” The regiment's companies at Fairfax Court House saw the smoke drifting into the sky from the battlefield, and soon they saw the physical results of the fighting as ambulances brought casualties back that afternoon. “A great many of the wounded were brought to the Court House,” wrote Second Lieutenant William McConnell of Company H. “It was indeed a sad scene—some with an arm or a leg shot off.”

Sgt. Ransom Bush, 37, of Company K had been put to work with a detail of men gathering food and livestock, but he also listened with his comrades, noting developments in a letter to his wife. “They are gitting at it purty hot By the firing of the guns they have Ben firing about one [h]our and it gets hotter all the while,” he wrote. By afternoon he added the bitter development: “The news is that they have Drove our men Back to Centervill [sic].”19

That news was correct—the Union army was defeated in the first major battle of the war, which Confederates would call the first Battle of Manassas. As cannon fire echoed over the landscape that morning, Capt. Sam DeGolyer hadn't been able to stand the waiting—he and some other officers and men headed toward the sound of the battle “to see the fight,” Dr. Chamberlain wrote. Other accounts said that DeGolyer volunteered to carry orders and messages from his generals to commanders in the field. Ultimately this question about DeGolyer's going into the battle would become a point of controversy among the top officers of the regiment.

Sgt. William F. Robinson of Company H, from Jackson, who'd been a dentist in civilian life and was about 24 or 25, said he was “off on a scout” that day. He was among the officers who went toward the battlefield and came within about a mile of it. “I could see the flash of the cannon, and volumes of smoke rise,” he wrote. Knowing his regiment could be ordered to move at any moment, he hurried back to Fairfax Station. But DeGolyer continued on into harm's way. Whether he was carrying messages or just trying to help in the confusion of crumbling Union lines, DeGolyer and the regiment's adjutant, Lt. Francis S. Earle, 24, of Grand Rapids, rode into Confederate lines. The fact that they and some other Union troops were dressed in gray uniforms meant it was impossible for the two sides to tell each other apart at times. “They saw two armed men carrying a wounded man on a litter,” Dr. Chamberlain wrote about what he'd heard of DeGolyer's and Earle's adventure. “They asked DeGolyer where the hospital was. He asked them what regiment they belong to. They said South Carolina First. He drew his revolver and ordered them to give up their arms.” Earle decided it was time to get back to Union lines, but DeGolyer pressed on and was captured. One report said that DeGolyer was last seen “telling the Captain of one of the Artillery Companies where to point his guns.” Another officer of the 4th Michigan, Lt. Simon B. Preston from Hudson, of Company F, was reportedly carrying dispatches that day to General McDowell. He was also captured.20

That afternoon or evening the two parts of the 4th Michigan reunited at Fairfax Court House to await developments as the defeated Union troops streamed back toward them. “I saw men who were so frightened that they threw away their blankets, guns and everything, to aid them in their flight,” said Dr. Chamberlain. Orvey Barrett wrote that part of the 4th Michigan was positioned along the road that led from the battlefield to Fairfax Court House, “ordered to stop all stragglers,” referring to men who were retreating without orders. “Talk of stopping a cyclone; it was impossible. The rush of soldiers, congressmen, and other civilians, from Washington, literally forced us from the highway.”21

Edward H. C. Taylor agreed. “I had the honor if arresting the flight of a Colonel of Pennsylvania troops, who left his Reg. and fled from the field of Battle,” he wrote. “Late in the afternoon when I had returned to Fairfax thinking all was going well with our troops on the advance I was suddenly startled by the order to ‘fall in.’ We took our places in rank and marched out a mile towards Bull's Run and halted for the purpose of stopping the flight of our men. Among the first we stopped was this Col. whom I stopped with my bayonet on his breast in spite of his drawn pistol which he vainly tried in his excitement to fire, but as he forgot to cock his pistol, I could afford to laugh at him.” The Company A man said they were able to hold the retreating men for a while, but “the crowd became so dense that we were forced to give way to their pressure.”22

Fred Meech of Company B said the 4th Michigan's men lay on their arms, expecting to be sent in to take up the fight as thousands of Union soldiers retreated. But when his regiment was finally ordered to get to their feet and march (late that night or early in the morning of July 22), he was disgusted to see that they, too, were heading back toward Washington. Sgt. William E. Limbarker of Company F called it “shameful” and “a disgraceful retreat,” a widely held opinion. “We could not have marched it any quicker if h-e-1-1 had been right at our feet,” Meech complained. Sergeant Bush was also angry and disappointed and he blamed his superiors. “Wee have got a corrages [courageous] lot officers,” he wrote with sarcasm. “As [soon] as the battle was over they ordered us to retreat to Washington.” Lieutenant DePuy insisted that Colonel Woodbury and the other officers were as outraged as their men that they hadn't been allowed to fight, “but as soldiers we must obey orders.”23 As it turned out later, Woodbury privately blamed his own lieutenant colonel, William Duffield, for claiming that orders arrived to start the regiment retreating, when in reality no such order was received.

Some men posted out in the darkness as pickets were angry to find the 4th Michigan marched off without telling them. “Well there we stood till 3 o'clock when we found out our regiment had retreated 3 hours before,” a peeved Charles Barlow wrote. They quickly picked up their packs and joined the great tide of soldiers, moving like so many refugees. “The sight was painful to behold, waggon loads of wounded men came pounding along over the rough roads,” Barlow continued, “& their groans sound in my ears yet.” Dr. Chamberlain, his assistant, and sick men who could walk also retreated from Fairfax Station, moving along the railroad line toward Alexandria. “Piles of ammunition, guns, and all kinds of stores were left for the enemy,” the doctor wrote. He was among many Union men able to board the train that shuttled back and forth from Alexandria along the line of the retreat, evacuating soldiers throughout the early morning hours of July 22.

Sergeant Robinson described the retreat along the road as “one moving body of panic stricken men, horses and wagons, some of the horses dashing madly through the crowd, without any riders.” “The loss is great,” wrote Bancroft in his diary, “the confusion greater.” At five in the morning it began to rain on the downhearted and angry men of his regiment. “When we got within about a mile of Washington we halted and camped under the shed of a brick kiln which sheltered us from some of the rain, and rested there that day and night and then [the next day] marched to our old camp on Meridian Hill where we are now,” Fred Meech said of the aftermath. Lieutenant Monteith was less negative than some. “Crossing Penn[sylvani]a. Ave. we rec[eive]d 3 cheers for retreating in good order while other Reg[imen]ts were completely scattered,” he wrote.24

Fortunately for these men the Confederate generals didn't follow up on their victory. Back in Washington, the Union army was now under the command of Gen. George McClellan, and Dr. Chamberlain soon felt that things were now going “a little more ‘ship shape’” as McClellan imposed order and discipline on the shaken troops. No one was yet sure whether the missing Captain DeGolyer and Lieutenant Preston had been killed or captured, but they were missed. “We all feel their loss severely,” the doctor wrote of the officers. “They were both respected and loved by the entire Regiment.” Chamberlain noted that DeGolyer had led by his strength and courage, uncomplaining about hardships and setting a fine example for his men; Preston had been an officer always ready to assist his men and try to see to their care and comfort. “Poor fellows! They were too rash and venturesome for their safety,” he wrote.25

The fact that DeGolyer and Preston were missing was good news, ironically, for one man—Pvt. Jim Tuttle. Because the officers who had him arrested for insubordination were now prisoners, Tuttle no longer faced court-martial. “No one else caring to prefer charges against me, I was released in time to help cover the retreat of the demoralized army,” he claimed. But the larger questions about how the war should be prosecuted, and how and why the army had been beaten so badly, weighed on the minds of many. Lieutenant Monteith, a religious man, saw it in religious terms: “What causes the most anxiety on my part is the wickedness of our own people,” he wrote. “I can see it in the army more than before, coming from all parts of the country & so generally demoralized that it seems if God would visit his wrath upon us. But then, ten righteous in Sodom would have saved it from his vengeance & this gives me strong hope that he will help us and we will come off conquerors.” Edward H. C. Taylor, a Democrat, saw the Confederate victory as a matter of “too many traitors at home” and what he felt was the weak administration of President Lincoln. Taylor thought the government should compromise with the South, and that the administration was filled with incompetent and politically ambitious men. He hoped McClellan would be given a free hand to fight the war as he saw fit, calling him “the salvation of the nation in this crisis.”26

Dr. Chamberlain felt he could explain Bull Run more objectively and analytically, now that he spoke with some Southerners and realized the war was not going to be “some fun.”: “We have underrated our enemy very much,” he wrote to his hometown newspaper. “They firmly believe they are in the right in this controversy; they are a brave people…. Now these people are fighting as they believe, to protect their hearth stones, their wives and children, and their property from the ruthless band of a hireling soldiery. Can we convince them of their error? Not by the destruction of private property.”27

He continued his thoughts on the battle's impact a few days later. Bull Run had shown the new soldiers, as well as himself, what really happened to men hit by gunfire. “I have numerous applications for discharges from those who have all at once discovered some old scars or injuries, which they affirmed at the time of their enlistment [had] never given them any inconvenience,” the assistant surgeon wrote. Recruiters, he noted, should be more particular about selecting men for service. “I would rather have 500 men of the right stripe that 1,000 of these fellows who make great promises at home. These same men are generally grumbling about their rations, finding fault and making others discontented who would otherwise be satisfied.” He advised community leaders back home to make sure that the families of the volunteers weren't reduced to poverty because their husbands and fathers joined the army. If women back home truly wanted to help, they could send jellies, preserves, and wine for the sick and old clothes, sheets, and other textile products that could be turned into cloths for medical uses.

The doctor also felt that the Bull Run defeat was not so much the fault of the soldiers as of the officers, and that there was anxiety on the part of officers now they were going to be tested on their knowledge of tactics. “That is a move in the right direction,” Chamberlain wrote. “Men who were made Major Generals on account of political influence were found not be the material for warriors. It was also found to be bad policy to learn them military tactics in the teeth of batteries, which were mowing down our men at such a fearful rate.” The doctor later claimed his letters about Bull Run enraged some people at home.28

But many men still wanted the chance to fight, to avenge those killed at Bull Run and defeat the Confederacy. One was David C. Laird, a 19-year-old Hillsdale County man in Company A, who heard grumbling from men who felt they shouldn't have to stay for their full three-year hitch. This idea came as a result of goings-on in the 1st Michigan Infantry, a “90-day” regiment. Before the battle, officers of the 1st Michigan had talked to their men about swearing an oath to fulfill a three-year hitch, but many of them refused, saying they wanted to return home first. On July 25, just four days after that regiment suffered at Bull Run, its men left for Detroit. Some members of the 4th Michigan—it is not clear how many—went with them, apparently having had their fill of army life.

Col. Dwight Woodbury wrote to state military authorities about the fact certain members of his regiment traveled home with the 1st Michigan—some with permission, some without. Two men from Company C who had never sworn into the service of the U.S. were allowed to go home, and the colonel had granted furlough to a soldier from Company F—but that was all. “All others are deserters,” Woodbury wrote, advising they should be arrested. Soldiers like young David Laird had no patience for the complainers and deserters. “I will not return [to Michigan] (if my life is spared) until the rebels are dispersed,” he vowed, though he understood now that the war was not going to be a short one. “I think the war will last three years, at least,” he wrote.29

The 4th Michigan returned to the routine of drill and work, or fatigue, on Meridian Hill, where they built a fort that was part of chain of defenses for Washington. Company I's Sgt. Michael J. Vreeland, 22, of Brownstown Township in Wayne County, said the regiment's discipline was strict and that the soldiers “were not allowed to leave the camp for any purpose whatsoever, so that for all the good it does, we are just as far from Washington as ever.” But 18-year-old Pvt. Stiles H. Wirts didn't let orders and guards stop him from having a good time. He bragged that he routinely sneaked out of camp to visit a couple of nearby families who happened to have charming daughters. Of course, Vreeland would ultimately leave the service of his country with the brevet (honorary) rank of a brigadier general, while Wirts soon became a prisoner of war, his military career ending much sooner. Officers and noncommissioned officers were allowed to leave camp, however. Sergeant Limbarker of Company F took a day to tour the Patent Office and the White House with one of his company's lieutenants. “Old [Abe] did not ask us to Drink or Dine with Him[,] the old Sucker,” Limbarker joked. The sergeant added that “he has pleasant place.”

The regiment didn't stay long on Meridian Hill. On August 8 the men marched with their brigade in the heat to Arlington Heights in the hilly, wooded Virginia countryside. Some described this as a few miles from Washington on the road to Fairfax Court House, or two or three miles out on the way to Fall's Church, where there were Confederate positions. They called this place Camp Union. Pickets here regularly traded fire with Confederates, initially, and there was the periodic false alarm. Sgt. John Bancroft noted that “Capt. S,” probably Jeremiah Slocum of Company I, fell into a regimental latrine or cesspool, a kind of a ditch, when the 4th Michigan was called out on a rainy night just days after they arrived. But the weather turned surprisingly cool for August and the men received some of their pay. The regiment's new brigade was briefly under the command of Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman. Sergeant Bancroft wrote to a Detroit newspaper that Sherman was “a plain, quiet sort of a man, but very prompt and business like in his actions.” Of course, Sherman would go on to be one of the war's great generals.30

Each morning, Lt. William McConnell told friends, one company from the 4th Michigan went on guard duty around the immediate vicinity of the camp while another went out on picket. Picket duty involved the posting of squads in advanced positions as frontline sentries, taking the men further into the countryside. Lt. George Monteith described one of the first picket assignments on August 9. Moving with 40 men, a few lieutenants, and three dragoons for carrying dispatches, he reached a crossroads about a mile and a half from Camp Union. When Confederates fired at his men and they fired back, the entire regiment hurried out in line of battle, though nothing came of this incident.31

This sort of disturbance would eventually prompt soldiers to realize that unless there was truly a threat of attack by the other side, picket firing served no good purpose except to risk injury or death to men who weren't in battle, but merely on routine duty. Such shooting also deprived of sleep the pickets' reserves and their comrades back in camp. In other words, most men would come to the conclusion that picket firing was a dangerous and pointless waste of everyone's time.

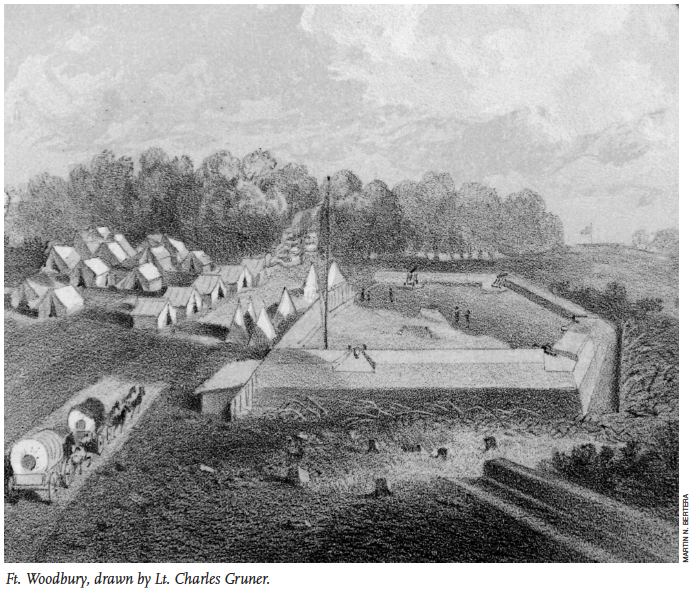

By the middle of the month, the 4th Michigan and their brigade were pulled back a mile or more toward the Potomac—the men could see Washington and Georgetown from this place—and the troops again built fortifications. The regiment proudly named their particular spot Fort Woodbury. A renewed confidence returned to troops dispirited over Bull Run. “If they attack us at this point, that is Arlington Heights, we are preparing to give them a warm reception,” wrote Washington W. Carpenter. “I tell you I begin to feel good at the prospects of an engagement.”

Other changes took place in late July and early August—in uniforms, weapons, and personnel. “We have been furnished with a blue uniform in place of the grey one, which bore too close a resemblance to that of the Secessionists,” wrote Private James Redfield of Company A, referring to the fact that soldiers hadn't been able to tell from friend from foe at Bull Run. The 4th Michigan's new clothing was described by another soldier as a “semi-Zouave” uniform with a fez, dark blue pants, and white or tan gaiters. Of course, the exotic head wear would also turn out to be temporary, for soldiers quickly learned that a fez simply couldn't keep the rain off a man's face as well as a forage cap with a visor or a slouch hat with a brim. More importantly, a soldier writing to a Detroit newspaper stated that Companies A and B (the regiment's “flanking companies,” received rifles that fired Minié balls (or “minnie balls,” as the soldiers called them). These rifles were far more accurate and had longer range than muskets. But not all the men got the better rifles. Many were given more “buck and ball” muskets, just like the ones they had been issued earlier.32

Sgt. Orvey S. Barrett of Company B later wrote that men weren't happy about these weapons, and some soldiers formed a noisy, mock “funeral procession” for the old muskets they turned in, accompanying the boxes to the quartermaster's depot, firing a “salute” over them, and attracting a lot of attention. Noticing that this spectacle drew a crowd, some of them formed a plan: When they went back to camp, 40 men from Company B engaged in more noisy shenanigans. Some strapped muskets onto their backs and got down on their hands and knees so that the barrel stuck out over their heads; others pulled the triggers with strings, firing off blanks. While this loud and distracting silliness was going on, another group of soldiers engaged the sutler (a licensed, traveling merchant) with the nearby 14th New York Infantry in conversation. But as the sutler was engaged and musket blanks were going off, a barrel of whiskey disappeared from his tent. “It was never found,” Barrett joked, “but you could buy a canteen full for $5 of one who knew where it was.” A detail was sent out to look for the missing whiskey, he noted with deadpan humor, but its members were quite drunk when they came back to camp.33

These sorts of high jinks were an exception. Jonas Richardson noted that “we practice at target shooting every morning.” Shortly after the 4th Michigan was moved back toward the Potomac in mid-August, Sergeant Richardson said that “the orders have been given not to fire on the Rebble [sic] pickets unless they fired on us first.” Capt. Alexander Crane of Company K, who had hurt his foot some weeks previously, was pressured by Governor Blair to resign; Crane did so. Capt. James Cole of Company B accidentally shot himself in the thigh with his revolver on August 18 and was removed back to a Washington area hospital. Moses Funk of Company H resigned, reportedly when a new federal law went into effect that no man over the age of 40 could be a captain, though some thought he hadn't been able to pass the new tactics examination.34

Dr. Joseph Tunnicliff Jr., the regiment's surgeon, resigned to become surgeon of the newly reorganized 1st Michigan Infantry, its new soldiers now required to serve a three-year hitch. Major Jonathan W. Childs wrote that the officers of the 4th Michigan had gotten along with each other well with the exception of Tunnicliff, whom Governor Blair had wanted to go into the regiment. Tunnicliff apparently was not satisfied with life as a military surgeon and spent much of his time away from the regiment, often attending Congress and not returning to camp for days. This was unacceptable to Colonel Woodbury, who asked the doctor to spend more time in camp, Childs said; Tunnicliff was unhappy with this request and went back to Michigan to get a different appointment. Another version of Tunnicliff's leaving (published in the hometown newspaper of Dr. Chamberlain and perhaps written by him) claimed that Tunnicliff hadn't been able to pass an examination by medical authorities. Whatever the reason for Tunnicliff's departure, Chamberlain believed he was going to be appointed to the post of regimental surgeon. But a number of people back in Michigan complained to Governor Blair about Chamberlain's published assessment of what was wrong with the Union army and the Lincoln administration's war effort—they thought the doctor unpatriotic. Chamberlain later wrote that Blair, in order to curry favor with those who wanted him punished, found another doctor to serve in the role of surgeon, leaving Chamberlain as assistant surgeon.

Lt. George Monteith got a desirable new assignment when Colonel Woodbury asked him if he would serve as adjutant for Sherman's brigade. This turned out to be the first in a series of jobs as staff officer or aide that would sometimes take young Monteith out of the regiment and get him better pay, food, and living arrangements. “Friday last I went out with Capt. Cole & Co. B on picket, he being destitute of suits, it was very wet & rainy, but my quarters were [are now] in a chapel,” he wrote from the headquarters of his brigade at Fort Corcoran. Monteith's letters show he was happy to be at division headquarters, though he still got assignments that took him to the picket line and, eventually, into battle.35

Back in camp with the 4th Michigan, Major Childs wrote that the officers of the regiment were downright angry with the Detroit Free Press correspondent who signed his dispatches “Hamilton” or “H.” The man's name was actually H. H. Finley, Childs said, and his reports had been unfair and inaccurate, “the blackest of bare faced lies,” stating that the officers had been quarrelsome, uncaring, and corrupt. “He is careful to keep without our lines,” the major wrote about Finley. “Should he enter them, the men would tar and feather him.” Edward Taylor also said press accounts of officers abusing or mistreating men were not true.36 As did many Civil War soldiers, Ned Taylor expressed anger at sutlers, the mobile merchants who sold goods at high prices to soldiers, who usually had nowhere else to shop. “It is a shame the way the Sutler (the authorized pedlar to the Reg.) charges,” he complained. “Gingerbread for which one cent in Geneva [N.Y.] would have been almost too much, he sells at five. Butter which could be bought, so the papers tell, in Michigan for seven he sells for fifty cents about…. He gets his price for he has no opposition.” In the meantime the soldiers of the regiment built fortifications and drilled, waiting for the day when they took the offensive. “Inform all enquiring friends that I am well and like my trade first rate,” wrote Sgt. Jonas Richardson to family.37

As the Union army drilled and worked on those August days, two men from the 4th Michigan figured in incidents and situations that made national headlines. First, in an odd piece of poetic justice, James Tuttle—the soldier who escaped court-martial after Capt. Sam DeGolyer was captured at Bull Run—also fell into Confederate hands. This happened when Company F was out on picket on August 10. “A considerable boddy of the enemy cavalry charged down on us and we made for the woods,” Tuttle wrote. But he and Pvt. Stiles H. Wirts—who previously enjoyed sneaking past the camp guard near Washington to go flirt with girls and pass worthless old Michigan banknotes—got separated from the rest of the company. They found themselves surrounded when they emerged from the woods. Over the next couple of days, the prisoners were marched to Centerville and then transported to a place Tuttle identified as Lynchburg. Here they were held in a vermin-infested jail in which they fought rats all night. Then they were taken to Richmond and placed in one of the tobacco warehouses now overflowing with Union prisoners. Perhaps even more ironic was that by the time Tuttle arrived in Richmond, Captain DeGolyer was no longer there—he had just escaped from Rebel prison and soon became a national hero to the North. Worse still for Tuttle, he now faced an even starker fate than court-martial: He was, he claimed, chosen as one of 151 Union prisoners who, in the lengthening summer of 1861, faced the prospect of being hanged by the Confederate States of America.38